First Fitna

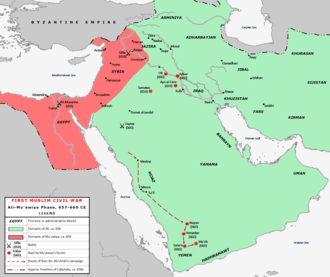

The First Fitna (Arabic: فتنة مقتل عثمان fitnat maqtal ʻUthmān "strife/sedition of the killing of Uthman") was a civil war within the Rashidun Caliphate which resulted in the overthrowing of the Rashidun caliphs and the establishment of the Umayyad dynasty. It began when the caliph Uthman was assassinated by rebels in 656 and continued through the four-year reign of Uthman's successor, Ali. It ended in 661 when Ali's heir Hasan ibn Ali concluded a treaty acknowledging the rule of Muawiyah, the first Umayyad caliph.[1]

| First Fitna | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Fitnas | |||||||

Region under the control of Caliph Ali

Region under the control of Caliph Mu'awiya | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rashidun Caliphate |

Aisha's forces Muawiyah's forces | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Ali Ammar ibn Yasir † Malik al-Ashtar |

Aisha Talha † Zubayr ibn al-Awam † Muawiyah I 'Amr ibn al-'As[b] | ||||||

| |||||||

Background

The Islamic caliphate expanded very quickly under the first three caliphs. Muawiyah I was appointed Governor of Syria by Umar in 639, after the previous Governor, Muawiyah's elder brother Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan, died in a plague along with Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah (the Governor before him) and 25,000 other people.[2]

The rapid Muslim conquest of the Levant and of Egypt and the consequent Byzantine losses in manpower and territory meant that the Eastern Roman Empire found itself struggling for survival. The Sasanian Empire had already collapsed.

The Islamic empire expanded at an unprecedented rate, but there was a cost associated with it. Many desert nomads and some bandits living between present-day Iraq and Saudi Arabia also joined in, not out of commitment to Islam but to share the spoils and benefit from the change in the social order, after the defeat of the Sasanian Empire.[3]

Before Islam, the Roman–Persian Wars and the Byzantine–Sasanian wars had occurred every few years for hundreds of years between 69 BCE and 629 CE. High taxes were imposed on the populations in both the Byzantine and Sassanid empires to finance these wars. There was also continuous bloodshed of the people during these wars. The Arab tribes in Mesopotamia were paid by the Sasanians to act as their mercenaries, while those in Syria were paid likewise by the Byzantines. Each side maintained an Arab satellite state – the Sasanians the Lakhmids, and the Byzantines the Ghassanids – which they used to fight each other in a proxy war.[4] The Syrians and the Mesopotamians had been fighting each other for centuries. Therefore, each wanted the capital of the newly established Islamic state to be in their area.[5]

As Uthman became very old, Marwan I, a relative of Muawiyah I, slipped into the vacuum and became his secretary, slowly assuming more control and relaxing some of these restrictions. Marwan I had previously been excluded from positions of responsibility.

Qurra dispute

There was also a movement towards more autonomous tribal groupings, which was particularly strong in Kufa, in Mesopotamia; they wanted to rule their own states. Among them developed a group called the Qurra, which later became known as the Kharijites.[3] The earliest reference to these people are as Ahl al-Qurra, the people of the village, those who fought with Abu Bakr against the desert tribes of Yamama during the Ridda wars when some of the tribes refused to pay the zakat.[6][7] Afterwards they were granted trusteeship over some of the lands in Sawad in Mesopotamia and were now called Ahl al Ayyam, those who had taken part in the eastern conquests.[8][3] Some modern scholars like R. E. Brunnow trace the origins of the Qurra and the Kharijites back to Bedouin stock and desert tribesmen, who had become soldiers not out of commitment to Islam but to share the spoils. Brunnow held that the Kharijites were Bedouin Arabs or full blooded Arabs.[9]

The Qurra received the highest stipend of the Muslim army and they had the use of the best lands that they came to regard as their private domain. The Qurra received stipends varying between 2000 and 3000 dirhams, while the majority of the rest of the troops received only 250 to 300 dirhams. The other Ridda tribesmen in Kufa in Mesopotamia, resented the special position given to the Qurra. The tension between the Ridda tribesmen and the Qurra threatened the Qurra's newly acquired prestige. The Qurra therefore felt obliged to defend their position in the new but rapidly changing society.

The Qurra were mainly based in Kufa.[10] They had not been involved in Syria. Later, when Uthman declined to give them more lands in Persia[8][11] they felt that their status was being reduced and therefore started to cause trouble.[11][12] He also removed the distinction between the Ridda and pre-Ridda tribesmen which was not to their liking and lessened their prestige.[8][13][14] As a result, they rebelled.[11][15][14][16]

Some of the people with their tribal names as Qurra had been expelled from Kufa, for fomenting trouble and were sent to Muawiyah in Syria. Then they were sent to Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid, who sent them to Uthman in Medina. In Medina they took an oath that they would not cause trouble and following the example of Muhammad, Uthman accepted their word and let them go.[17] They then split up and went to various different Muslim centers and started fomenting rebellion, particularly in Egypt.

The Qurra then felt that Abu Musa al-Ash'ari could look after their interests better. In 655 the Qurra stopped Uthman's governor Sa'id ibn al-'As at Jara'a, preventing him from entering Kufa and declared Abu Musa al-Ashari to be their governor.[18]

In 656, the Qurra approached Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr, the son of Abu Bakr and the adopted son of Ali and asked him why he was not a governor. They had fought under the service of his father in the Ridda wars. They also asked Uthman's adopted son, Muhammad ibn Abi Hudhayfa, who Uthman had refused to appoint as a governor of any province, why he was not a governor.

Siege of Uthman

As Muawiyah and Caliph Uthman were preparing to besiege Constantinople, in 656, Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr showed some Egyptians the house of Uthman. Finding the gate of Uthman's house strongly guarded by his supporters, the Qurra climbed the back wall and sneaked inside, leaving the guards on the gate unaware of what was going on inside. Hassan and Hussein were also guarding Uthman at the time.[19] The rebels entered his room and struck him on the head.[20]

Uthman had been besieged in his palace for 49 days before he was killed. Ali had done a great deal to attempt to save Uthman; however, Marwan prevented Ali from being able to help Uthman. Uthman only listened to the advice of Marwan and Saeed bin Aas, and Marwan did his best to act as a barrier between Ali and Uthman.[21]

Uthman's death had a polarizing effect in the Muslim world at the time. Questions were raised not only regarding his character and policies but also about the relationship between Muslims and the state, religious beliefs regarding rebellion and governance, and the qualifications of rulership in Islam.[22]

Succession of Ali

The people of Medina asked Ali, who had been chief judge in Medina, to become the Caliph and he accepted.

Muawiyah I, the governor of Syria, a relative of Uthman, and Marwan I wanted the murderers of Uthman arrested, and blamed Ali for it, Ali claimed that he was not responsible for Uthman's murder, but the conspirators continued the conspiracies. The conspirators felt that if there was peace, they would be arrested for the killing of Uthman.[23] Many of them later became the Kharijites and eventually killed Ali.

Battle of the Camel

Aisha bint Abu Bakr (Muhammad's widow), Talhah ibn Ubayd-Allah, and Zubayr ibn al-Awam opposed Ali's succession and gathered in Mecca calling for vengeance against Uthman's killers and election of new caliph through Shura. Later they moved to Basra taking it from Ali's governor, with the intention of strengthening their numbers. Ali in response sent his son Hasan and the leaders of Kufan mutineers to raise an army in Kufa. Ali himself followed them soon; with the combined army, they marched against Basra.[24]

The armies met outside Basra. After three days of failed negotiations, battle started in the afternoon of 8 December 656 and lasted till the evening. Zubayr left the field without fighting but was pursued and killed. Ali's army emerged victorious and Talha was also killed. After admonishing Ayesha, Ali sent her back to Medina, escorted by her brother Muhammad ibn Abu Bakr.[25] Marwan probably paid allegiance to Ali and the latter let him go.[25]

Battle of Siffin

.jpg)

Ali's inability to punish the murderers of Uthman and Muawiyah's refusal to pledge allegiance eventually led Ali to move his army north to confront Muawiyah. The two armies encamped themselves at Siffin for more than one hundred days, most of the time being spent in negotiations. Neither side wanted to fight. Then on 29 July 657 (11th Safar), the Mesopotamians under Ashtar's command, the Qurra in Ali's army, who had their own camp, started the fighting in earnest. The battle lasted three days. The loss of life was terrible. Suddenly one of the Syrians, Ibn Lahiya, out of fear of further civil war and unable to bear the spectacle rode forward with a copy of the Quran on the ears of his horse to call for judgement by the book of Allah, and the other Syrians followed suit. Everyone on both sides took up the cry, eager to avoid killing their fellow Muslims - except for the conspirators. The majority of Ali's followers supported arbitration. Nasr b Muzahim, in one of the earliest sources states that al-Ashath ibn Qays, one of Ali's key supporters and a Kufan, then stood up and said:

O company of Muslims! You have seen what happened in the day which has passed. In it some of the Arabs have been annihilated. By Allah, I have reached the age which Allah willed that I reach. but I have never ever seen a day like this. Let the present convey to the absent! If we fight tomorrow, it will be the annihilation of the Arabs and the loss of what is sacred. I do not make this statement out of fear of death, but I am an aged man who fears for the women and children tomorrow if we are annihilated. O Allah, I have looked to my people and the people of my deen and not empowered anyone. There is no success except by Allah. On Him I rely and to Him I return. Opinion can be both right and wrong. When Allah decides a matter, He carries it out whether His servants like it or not. I say this and I ask Allah's forgiveness for me and you.

Then, Nasr b Muzahim says people looked at Muawiya who said

He is right, by the Lord. If we meet tomorrow the Byzantines will attack our women and children and the people of Persia will attack the women and children of Mesopotamia. Those with forebearance and intelligence see this. Tie the copies of the Quran to the ends of the spears.

So the fighting stopped.[26]

Every time Ali tried to negotiate the Qurra and the Sabait started wars and launched night attacks, fearing that if there was peace, then they will be arrested.[27]

Arbitration

It was decided that the Syrians and the residents of Kufa should nominate an arbitrator, each to decide between 'Ali and Mu'awiya. The Syrians' choice fell on 'Amr bin al-A'as who was the rational soul and spokesman of Muawiya. 'Amr ibn al-'As was one of the generals involved in conquering Syria and also Egypt.[28] A few years earlier 'Amr ibn al-'As with 9,000 men in Palestine had found himself confronting Heraclius' 100,000 army until Khalid crossed the Syrian desert from Mesopotamia to assist him.[28] He was a highly skilled negotiator and had previously been used in negotiations with the Heraclius the Roman Emperor.[29] Ali wanted Malik Ashtar or Abdullah bin 'Abbas to be appointed as an arbitrator for the people of Kufa, but the Qurra strongly demurred, alleging that men like these two were responsible for the war and, therefore, ineligible for that office of trust. They nominated Abu Musa al-Ash'ari as their arbitrator (during the time of 'Uthman, they had appointed Abu Musa al-Ash'ari as the Governor of Kufa and removed 'Uthman's governor before they started fighting 'Uthman). Ali found it expedient to agree to this choice in order to ward off bloody dissension in his army. According to Usd al-G̲h̲āba, Ali therefore took care to personally explain to the arbitrators, "You are arbiters on condition that you decide according to the Book of God, and if you are not so inclined you should not deem yourselves to be arbiters."[30]

When the arbitrators assembled at Dumat al-Jandal, which lay midway between Kufa and Syria and had for that reason been selected as the place for the announcement of the decision, a series of daily meetings were arranged for them to discuss the matters in hand. When the time arrived for taking a decision about the caliphate, Amr bin al-A'as convinced Abu Musa al-Ashari that they should deprive both Ali and Mu'awiya of the caliphate, and give the Muslims the right to elect the caliph. Abu Musa al-Ash'ari decided to act accordingly. As the time for announcing the verdict approached, the people belonging to both parties assembled. 'Amr bin al-A'as requested Abu Musa take the lead in announcing the decision he favoured. Abu Musa al-Ash'ari agreed to open the proceedings, and said, "We have devised a solution after a good deal of thought and it may put an end to all contention and separatist tendencies. It is this. Both of us remove 'Ali as well as Mu'awiya from the caliphate. The Muslims are given the right to elect a caliph as they think best."[31] On his turn 'Amr bin al-A'as stated that he agreed with the part of Abu Musa Ash'ari's verdict that 'Ali should be deposed but he himself was in favour of retaining Mua'wiyah on his post.

Ali refused to accept the verdict.[32][33][34] This put Ali in a weak position even amongst his own supporters.[32] The most vociferous opponents of Ali in his camp were the very same people who had forced Ali to appoint their arbitrator, the Qurra.[31] Feeling that Ali could no longer look after their interests[11] and that they could be arrested for the murder of 'Uthman if there were peace, they broke away from Ali's force, rallying under the slogan, "arbitration belongs to God alone."[31] The Qurra then became known as the Kharijites ("those who leave").

Conflict with Kharijites

In 659 Ali's forces finally moved against the Kharijites and they finally met in the Battle of Nahrawan. Although Ali won the battle, the constant conflict had begun to affect his standing.[31] Tom Holland writes "Ali won a victory over them as crushing as it was to prove pyrrhic: for all he had done, in effect was to fertilise the soil of Mesopotamia with the blood of their martyrs. Three years later, and there came the inevitable blowback: a Kharijite assassin."[35]

While dealing with the Iraqis, Ali found it hard to build a disciplined army and effective state institutions to exert control over his areas and as a result later spent a lot of time fighting the Kharijites. As a result, on the Eastern front, Ali found it hard to expand the state.[36]

Ali was assassinated by Kharijites in 661. On the 19th of Ramadan, while Praying in the Great Mosque of Kufa, Ali was attacked by the Kharijite Abd-al-Rahman ibn Muljam. He was wounded by ibn Muljam's poison-coated sword while prostrating in the Fajr prayer.[37] When Alī was assassinated, Muawiyah had the largest and the most organized and disciplined force in the Muslim Empire.

Peace treaty with Hassan

Six months later in 661, in the interest of peace, Hasan ibn Ali made a peace treaty with Muawiyah. By now Hassan only ruled the area around Kufa. In the Hasan-Muawiya treaty, Hasan ibn Ali handed over power to Muawiya on the condition that he be just to the people and keep them safe and secure and after his death he does not establish a dynasty.[38]

In the year 661, Muawiyah was crowned as caliph at a ceremony in Jerusalem.[39] Ali's caliphate had lasted for four years. After the treaty with Hassan, Muawiyah ruled for nearly 20 years[1] most of which were spent expanding the state.

Footnotes

- Martin Hinds. "Muʿāwiya I". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Weston, Mark (2008). Prophets and Princes: Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-470-18257-4.

- Timani, Hussam (2008). Modern Intellectual Readings of the Kharijites. Peter Lang. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8204-9701-3.

- A Chronology Of Islamic History 570-1000 CE, By H.U. Rahman 1999 Page 10

- Iraq a Complicated State: Iraq's Freedom War By Karim M. S. Al-Zubaidi Page 32

- Timani, Hussam (2008). Modern Intellectual Readings of the Kharijites. Peter Lang. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8204-9701-3.

- Muawiya Restorer of the Muslim Faith by Aisha Bewley, page 14, with text from Al-Baladuri

- Muawiya Restorer of the Muslim Faith By Aisha Bewley Page 13

- Modern Intellectual Readings of the Kharijites By Hussam S. Timani Page 49

- Timani, Hussam (2008). Modern Intellectual Readings of the Kharijites. Peter Lang. pp. 61–65. ISBN 978-0-8204-9701-3.

- Modern Intellectual Readings of the Kharijites By Hussam S. Timani Page 61-65 about the writings of M. A. Shahban, In his Islamic History A.D. 600-750 (A.H. 132): A new Interpretation (1971)

- Kirk H. Sowell (2004). The Arab World: An Illustrated History. Hippocrene Books. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-7818-0990-0.

- Modern Intellectual Readings of the Kharijites By Hussam S. Timani Page 61

- Muawiya Restorer of the Muslim Faith By Aisha Bewley Page 14 with text from Al-Baladuri

- Hussam S. Timani (2008). Modern Intellectual Readings of the Kharijites. Peter Lang. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8204-9701-3.

- Ahmad Bin Yahya Bin Jabir Al Biladuri (1 March 2011). The Origins of the Islamic State: Being a Translation from the Arabic Accompanied With Annotations, Geographic and Historic Notes of the Kitab Futuh Al-buldan. Cosimo, Inc. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-61640-534-2.

- Muawiya Restorer of the Muslim Faith By Aisha Bewley Page 16

- Muawiya Restorer of the Muslim Faith By Aisha Bewley Page 14

- A Chronology Of Islamic History 570-1000 CE, By H.U. Rahman 1999 Page 53

- The Many Faces of Faith: A Guide to World Religions and Christian Traditions By Richard R. Losch

- Razwy, Sayed Ali Asgher. A Restatement of the History of Islam & Muslims. p. 536.

- Valerie Jon Hoffman, The Essentials of Ibadi Islam, pg. 8. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2012. ISBN 9780815650843

- Hadhrat Ayesha Siddiqa By Allamah Syed Sulaiman Nadvi Page 44

- Donner 2010, p. 158–160.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 168–174.

- Muawiya Restorer of the Muslim Faith By Aisha Bewley Page 22 from Ibn Hisham from Ibn Muzahim died 212 AH from Abu Mikhnaf died 170 AH

- Hadhrat Ayesha Siddiqa her life and works by Allamah Syed Sulaiman Nadvi translated by Syed Athar Husain and published by Darul Ishaat Page 44

- Islamic Conquest of Syria A translation of Fatuhusham by al-Imam al-Waqidi Translated by Mawlana Sulayman al-Kindi, Page 31 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-09-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Islamic Conquest of Syria A translation of Futuh ash-Sham by al-Waqidi Translated by Sulayman al-Kindi "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-09-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Usd al-G̲h̲āba", vol 3, p. 246. Name of book needed

- H.U. Rahman, A Chronology of Islamic History 570-1000 CE, p.59

- H.U. Rahman, A Chronology of Islamic History 570-1000 CE, p.60

- Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia edited by Alexander Mikaberidze, p. 836

- Ground Warfare: H-Q edited by Stanley Sandler, p. 602. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- In the shadow of the sword, The Battle for Global Empire and the End of the Ancient World By Tom Holland, ISBN 978-0-349-12235-9 Abacus Page 399

- A Chronology of Islamic History 570-1000 By H. U. Rahman

- name="Tabatabaei 1979 192"

- The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate By Wilferd Madelung Page 232

- History of Israel and the Holy Land By Michael Avi-Yonah, Shimon Peres. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

References

- Ali ibn Abi Talib (1984). Nahj al-Balagha (Peak of Eloquence), compiled by ash-Sharif ar-Radi. Alhoda UK. ISBN 0-940368-43-9.

- Donner, Fred M. (2010). Muhammad and the Believers, at the Origins of Islam. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05097-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holt, P. M.; Bernard Lewis (1977). Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29136-4.

- Lapidus, Ira (2002). A History of Islamic Societies (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64696-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tabatabae, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1979). Shi'ite Islam. Translated by Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Suny press. ISBN 0-87395-272-3.

- Encyclopedia

- Encyclopædia Iranica. Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University. ISBN 1-56859-050-4. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

External links

- The relationship between Jews and baatini (esoteric) sects (from a Sunni perspective)

Further reading

- Djaït, Hichem (2008-10-30). La Grande Discorde: Religion et politique dans l'Islam des origines. Editions Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-035866-6. Arabic translation by Khalil Ahmad Khalil, Beirut, 2000, Dar al-Tali'a.