Al-Hakim Mosque

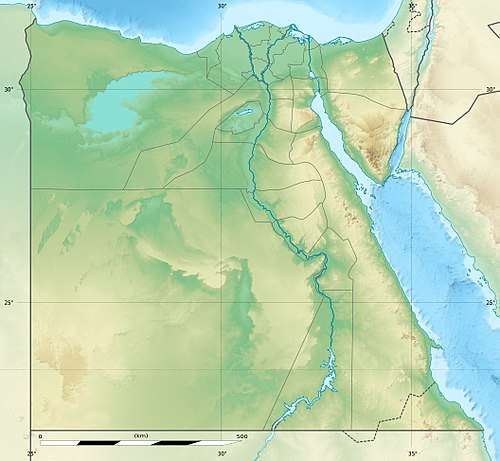

The Mosque of al-Hakim (Arabic: مسجد الحاكم بأمر الله, romanized: Masjid al-Ḥākim bi Amr Allāh), nicknamed al-Anwar (Arabic: الانور, lit. 'the Illuminated'),[1] is a major Islamic religious site in Cairo, Egypt. It is named after Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (985–1021), the sixth Fatimid caliph and 16th Ismaili Imam. This mosque originally started being built by al-Aziz, the son of Mu'izz, and the father of al Hakim, in 990 A.D.[2] It was named after Al Hakim because he has finished it.[3]

| |

|---|---|

مسجد الحاكم بأمر الله | |

Interior courtyard of the mosque | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Region | Cairo |

| Ecclesiastical or organisational status | Mosque |

| Year consecrated | 928 CE |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Muizz Street |

| Country | Egypt |

Location in Cairo | |

| Geographic coordinates | 30°03′16″N 31°15′49″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Fatimid |

| Founder | Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah |

| Completed | 992 CE |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 1 |

| Minaret(s) | 2 |

This Fatimid style mosque was built for over twenty years at great cost. The interior of the mosque is an open courtyard with parallel columns, forming a rectangle shape all around. In late 1010, Al Hakim ordered for the minarets to be at an angle and that the columns of the masjid to be very tall to cover the inside of the mosque.[4] The mosque's walls were symmeterically arranged within each other. The mosque had originally more than thirteen entrances[5] hence the open space courtyard, one can enter from wherever. Masjid Al Hakim is very similar in architectural design with the Mosque of ibn Tulun: It consists of an irregular rectangle with four arcades surrounding the courtyard. An unusual feature is the monumental entrance with its projecting stone porch.[6] It is located in Islamic Cairo, on the east side of Muizz Street, just south of Bab Al-Futuh (the northern gate).

The minarets

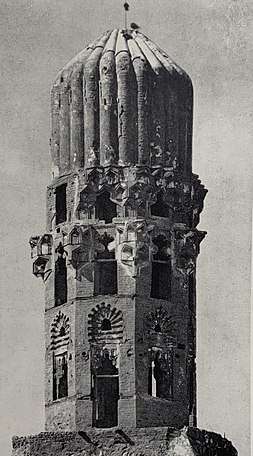

The most spectacular feature of the mosque are the minarets on either side of the facade.

Originally the two minarets stood independent of the brick walls at the corners. These are the earliest surviving minarets in the city and they have been restored at various times during their history. The massive salients were added in 1010 to strengthen their structure, and the northern minaret was incorporated into the city wall. Inside, these strange structures are hollow, for they have been built around the original minarets, which are connected with brackets and can still be seen from the minaret below. A picture of an old minaret from years ago from masjid Al Hakim is displayed below in black and white to the right. It is the mabkhara finial of northern minaret from this Masjid.[7]

Name plate

There was name plate engraved on stone located at the top of entrance gate facing inside of Mosque. This plate got damaged with time and, one piece of it was found during renovation work. When enquired with archeological authorities few more pieces of the plate were recovered. With further research the details about missing piece of the name plates were collected, replica of missing part were made and, complete name plate was reinstalled at its original location by Dawoodi Bohra Spiritual Leader, Dr. Syedna Mohammad Burhanuddin.(as per photo placed). Few pieces in the name plate which looks old and having dark color are the original ones. Fourth line ending part and beginning of fifth line of the name plate mention the name of Imam "Haakim amar-i-llah" in Kufi Arabic scripts.

Another name plate of marble (photo placed) is installed just below the main name plate during renovation work, having details about the history of the Mosque and its renovation work done.

Post-Fatimid era

At various times, the mosque was used as a prison for captured Franks (i.e. Latin crusaders) during the Crusades, as a stable by Saladin, as a fortress by Napoleon, and as a local school. As a result of this the mosque had fallen out of use. The condition of the structure was as such that few portion of the mosque is left out as shown in the photo of ruins placed in gallery.

In 1980 ACE/1401 AH, the mosque was extensively refurbished in white marble and gold trim by Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin the head of the Dawoodi Bohra, an international Ismaili sect based in India. Remnants of the original decorations, including stucco carvings, timber tie-beams, and Quranic inscriptions were restored as part of the renovations. His intent to restore the ancient Al-Hakim Mosque as a place of worship in contemporary times necessitated a lighting solution that provided this important functionality to the mosque and did so in a manner that paid tribute to the Fatimid tradition of illumination and its aesthetics. The miraculous emergence of the mishkat or small lantern from the niche of the richly decorated façade of Al Jami al Aqmar provided that solution. The niche in which the lantern motif was found has also been compared to the mihrab niche of Al Azhar mosque, the same also now found in Al-Hakim mosque, which has a central motif that resembles a large lamp or lantern.[8][9]

Today

Today the mosque is a place of worship. Its unique minarets attracts local and foreign tourists. Al-Hakim Mosque is now a place for Egyptians to pray and enjoy the calm and peacefulness of the mosque.

Gallery

- Courtyard fountain

Main mihrab

Main mihrab Entrance gate

Entrance gate encryption over entrance

encryption over entrance courtyard an overall view

courtyard an overall view qibla

qibla chandelier near qibla

chandelier near qibla Minaret de la Mosquée El-Hakem

Minaret de la Mosquée El-Hakem_-_TIMEA.jpg) Mosque of Al-Hakim in 1878

Mosque of Al-Hakim in 1878 Window of Anwar showing Miskas (lantern just above hexagonal figure) design used in Fatemi mosque

Window of Anwar showing Miskas (lantern just above hexagonal figure) design used in Fatemi mosque_Aqmar_Mosque.jpg) Phanus (Fatimid lamp) original carvings in stone at left wing of the façade of Aqmar.

Phanus (Fatimid lamp) original carvings in stone at left wing of the façade of Aqmar.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Al-Hakim Mosque. |

References

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1989). "The mosque of Caliph al-Ḥākim bi Amr Allāh (990–1003)". Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction. BRILL. pp. 63–65. ISBN 90-04-09626-4.

- King, James Roy (1984). "The Restoration of the Al-Ḥākim Mosque in Cairo". Islamic Studies. 23 (4): 325–335. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20847278.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (1983). "The Mosque of al-Ḥākim in Cairo". Muqarnas. 1: 15–36. doi:10.2307/1523069. JSTOR 1523069.

- Hoag, John D. (1987). Islamic architecture. Faber. ISBN 0-571-14868-9. OCLC 924758720.

- Hoag, John D. (1987). Islamic architecture. Faber. ISBN 0-571-14868-9. OCLC 924758720.

- Williams, Caroline; Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1992). "Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction. Vol. III". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 29: 226–229. doi:10.2307/40000513. ISSN 0065-9991. JSTOR 40000513.

- Wilber, Donald N.; Creswell, K. A. C. (December 1954). "The Muslim Architecture of Egypt, I. Ikhshids and Fatimids, A.D. 939-1171". The Art Bulletin. 36 (4): 304. doi:10.2307/3047582. ISSN 0004-3079. JSTOR 3047582.

- El Barbary, Mohamed; Al Tohamy, Aisha; Ali, Ehab (2017-02-01). "Shiite Connotations on Islamic Artifacts from the Fatimid period (358-567 A.H./969-1171 A.D.) Preserved in the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo". International Journal of Heritage, Tourism and Hospitality. 11 (3 (Special Issue)): 121–137. doi:10.21608/ijhth.2017.30225. ISSN 2636-414X.

- King, James Roy (1984). "The Restoration of the Al-Ḥākim Mosque in Cairo". Islamic Studies. 23 (4): 325–335. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20847278.