Palestinians

The Palestinian people (Arabic: الشعب الفلسطيني, ash-sha‘b al-Filasṭīnī), also referred to as Palestinians (Arabic: الفلسطينيون, al-Filasṭīniyyūn; Hebrew: פָלַסְטִינִים) or Palestinian Arabs (Arabic: الفلسطينيين العرب, al-Filasṭīniyyīn al-ʿarab), are an ethnonational group[31][32][33][34][35][36][37] comprising the modern descendants of the peoples who have lived in Palestine continuously over the centuries and who today are largely culturally and linguistically Arab;[38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45] including those ethnic Jews and Samaritans who fit this definition.

الفلسطينيون al-Filasṭīnīyūn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| c. 13 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 4,750,000[2][3][lower-alpha 1] | |

| – West Bank | 2,930,000 (of whom 809,738 are registered refugees (2017))[4][5][6] |

| – Gaza Strip | 1,880,000 (of whom 1,386,455 are registered refugees (2018))[2][4][5] |

| 2,175,491 (2017, registered refugees only)[4]–3,240,000 (2009)[7] | |

| 1,890,000[8][9] (60% of Israeli Arabs identify as Palestinians (2012))[10] | |

| 552,000 (2018, registered refugees only)[4] | |

| 500,000[11] | |

| 174,000 (2017 census)[12]–458,369 (2016 registered refugees)[4] | |

| 400,000[13] | |

| 295,000[13] | |

| 255,000[14] | |

| 91,000[13] | |

| 80,000[15] | |

| 80,000[16] | |

| 70,000[13] | |

| 70,000[17] | |

| 59,000[18] | |

| 59,000[13] | |

| 57,000[19] | |

| 50,975[20] | |

| 29,000[13] | |

| 27,000–200,000[13][21] | |

| 20,000[15] | |

| 15,000 | |

| 13,000[13] | |

| 12,000[13] | |

| 9,000–15,000[22] | |

| 7,000 (rough estimate)[23][24] | |

| 7,000[25] | |

| 4,030[26] | |

| Languages | |

| Palestine and Israel: Palestinian Arabic, Hebrew, English and Greek Diaspora: Other varieties of Arabic, the vernacular languages of other countries in the Palestinian diaspora | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Sunni Islam Minority: Christianity, Samaritanism,[27][28] Druze, Shia Islam, non-denominational Muslims[29] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Levantines, other Semitic-speaking peoples, Jews (Ashkenazim, Mizrahim, Sephardim), Assyrians, Samaritans, other Arabs, and other Mediterranean peoples.[30] | |

Despite various wars and exoduses (such as that of 1948), roughly one half of the world's Palestinian population continues to reside in historic Palestine, the area encompassing the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and Israel.[46] In this combined area, as of 2005, Palestinians constituted 49% of all inhabitants,[47] encompassing the entire population of the Gaza Strip (1.865 million),[48] the majority of the population of the West Bank (approximately 2,785,000 versus about 600,000 Jewish Israeli citizens, which includes about 200,000 in East Jerusalem) and 20.95% of the population of Israel proper as Arab citizens of Israel.[49][50] Many are Palestinian refugees or internally displaced Palestinians, including more than a million in the Gaza Strip,[51] about 750,000 in the West Bank[52] and about 250,000 in Israel proper. Of the Palestinian population who live abroad, known as the Palestinian diaspora, more than half are stateless, lacking citizenship in any country.[53] Between 2.1 and 3.24 million of the diaspora population live as refugees in neighboring Jordan,[54][55] over 1 million live between Syria and Lebanon and about 750,000 live in Saudi Arabia, with Chile's half a million representing the largest concentration outside the Middle East.

Palestinian Christians and Muslims constituted 90% of the population of Palestine in 1919, just before the third wave of Jewish immigration under the post-WW1 British Mandatory Authority,[56][57] opposition to which spurred the consolidation of a unified national identity, fragmented as it was by regional, class, religious and family differences.[58][59] The history of a distinct Palestinian national identity is a disputed issue amongst scholars.[60][61] Legal historian Assaf Likhovski states that the prevailing view is that Palestinian identity originated in the early decades of the 20th century,[60] when an embryonic desire among Palestinians for self-government in the face of generalized fears that Zionism would lead to a Jewish state and the dispossession of the Arab majority crystallised among most editors, Christian and Muslim, of local newspapers.[62] "Palestinian" was used to refer to the nationalist concept of a Palestinian people by Palestinian Arabs in a limited way until World War I.[42][43] After the creation of the State of Israel, the exodus of 1948 and more so after the exodus of 1967, the term came to signify not only a place of origin but also the sense of a shared past and future in the form of a Palestinian state.[42] Modern Palestinian identity now encompasses the heritage of all ages from biblical times up to the Ottoman period.[63]

Founded in 1964, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) is an umbrella organization for groups that represent the Palestinian people before international states.[64] The Palestinian National Authority, officially established in 1994 as a result of the Oslo Accords, is an interim administrative body nominally responsible for governance in Palestinian population centers in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.[65] Since 1978, the United Nations has observed an annual International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People. According to Perry Anderson, it is estimated that half of the population in the Palestinian territories are refugees and that they have collectively suffered approximately US$300 billion in property losses due to Israeli confiscations, at 2008–09 prices.[66]

Etymology

The Greek toponym Palaistínē (Παλαιστίνη), with which the Arabic Filastin (فلسطين) is cognate, first occurs in the work of the 5th century BCE Greek historian Herodotus, where it denotes generally[67] the coastal land from Phoenicia down to Egypt.[68][69] Herodotus also employs the term as an ethnonym, as when he speaks of the 'Syrians of Palestine' or 'Palestinian-Syrians',[70] an ethnically amorphous group he distinguishes from the Phoenicians.[71][72] Herodotus makes no distinction between the Jews and other inhabitants of Palestine.[73]

The Greek word reflects an ancient Eastern Mediterranean-Near Eastern word which was used either as a toponym or ethnonym. In Ancient Egyptian Peleset/Purusati[74] has been conjectured to refer to the "Sea Peoples", particularly the Philistines.[75][76] Among Semitic languages, Akkadian Palaštu (variant Pilištu) is used of 7th-century Philistia and its, by then, four city states.[77] Biblical Hebrew's cognate word Plištim, is usually translated Philistines.[78]

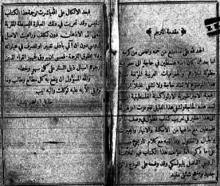

Syria Palestina continued to be used by historians and geographers and others to refer to the area between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, as in the writings of Philo, Josephus and Pliny the Elder. After the Romans adopted the term as the official administrative name for the region in the 2nd century CE, "Palestine" as a stand-alone term came into widespread use, printed on coins, in inscriptions and even in rabbinic texts.[79] The Arabic word Filastin has been used to refer to the region since the time of the earliest medieval Arab geographers. It appears to have been used as an Arabic adjectival noun in the region since as early as the 7th century CE.[80] The Arabic newspaper Falastin (est. 1911), published in Jaffa by Issa and Yusef al-Issa, addressed its readers as "Palestinians".[81]

During the Mandatory Palestine period, the term "Palestinian" was used to refer to all people residing there, regardless of religion or ethnicity, and those granted citizenship by the British Mandatory authorities were granted "Palestinian citizenship".[82] Other examples include the use of the term Palestine Regiment to refer to the Jewish Infantry Brigade Group of the British Army during World War II, and the term "Palestinian Talmud", which is an alternative name of the Jerusalem Talmud, used mainly in academic sources.

Following the 1948 establishment of Israel, the use and application of the terms "Palestine" and "Palestinian" by and to Palestinian Jews largely dropped from use. For example, the English-language newspaper The Palestine Post, founded by Jews in 1932, changed its name in 1950 to The Jerusalem Post. Jews in Israel and the West Bank today generally identify as Israelis. Arab citizens of Israel identify themselves as Israeli, Palestinian or Arab.[83]

The Palestinian National Charter, as amended by the PLO's Palestinian National Council in July 1968, defined "Palestinians" as "those Arab nationals who, until 1947, normally resided in Palestine regardless of whether they were evicted from it or stayed there. Anyone born, after that date, of a Palestinian father – whether in Palestine or outside it – is also a Palestinian."[84] Note that "Arab nationals" is not religious-specific, and it includes not only the Arabic-speaking Muslims of Palestine, but also the Arabic-speaking Christians of Palestine and other religious communities of Palestine who were at that time Arabic-speakers, such as the Samaritans and Druze. Thus, the Jews of Palestine were/are also included, although limited only to "the [Arabic-speaking] Jews who had normally resided in Palestine until the beginning of the [pre-state] Zionist invasion." The Charter also states that "Palestine with the boundaries it had during the British Mandate, is an indivisible territorial unit."[84][85]

Origins

The origins of Palestinians are complex and diverse. The region was not originally Arab – its Arabization was a consequence of the inclusion of Palestine within the rapidly expanding Arab Empire conquered by Arabian tribes and their local allies in the first millennium, most significantly during the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 7th century. Palestine, then part of the Byzantine Diocese of the East, a Hellenized region with a large Christian population, came under the political and cultural influence of Arabic-speaking Muslim dynasties, including the Kurdish Ayyubids. From the conquest down to the 11th century, half of the world's Christians lived under the new Muslim order and there was no attempt for that period to convert them.[86] Over time, nonetheless, much of the existing population of Palestine was Arabized and gradually converted to Islam.[38] Arab populations had existed in Palestine prior to the conquest, and some of these local Arab tribes and Bedouin fought as allies of Byzantium in resisting the invasion, which the archaeological evidence indicates was a 'peaceful conquest', and the newcomers were allowed to settle in the old urban areas. Theories of population decline compensated by the importation of foreign populations are not confirmed by the archaeological record[87][88] Like other "Arabized" Arab nations the Arab identity of Palestinians, largely based on linguistic and cultural affiliation, is independent of the existence of any actual Arabian origins. The Palestinian population has grown dramatically. For several centuries during the Ottoman period the population in Palestine declined and fluctuated between 150,000 and 250,000 inhabitants, and it was only in the 19th century that a rapid population growth began to occur.[89]

Pre-Arab/Islamic Influences on the Palestinian national identity

While Palestinian culture is primarily Arab and Islamic, many Palestinians identify with earlier civilizations that inhabited the land of Palestine.[90] According to Walid Khalidi, in Ottoman times "the Palestinians considered themselves to be descended not only from Arab conquerors of the seventh century but also from indigenous peoples who had lived in the country since time immemorial."

Similarly Ali Qleibo, a Palestinian anthropologist, argues:

Throughout history a great diversity of peoples has moved into the region and made Palestine their homeland: Canaanites, Jebusites, Philistines from Crete, Anatolian and Lydian Greeks, Hebrews, Amorites, Edomites, Nabataeans, Arameans, Romans, Arabs, and Western European Crusaders, to name a few. Each of them appropriated different regions that overlapped in time and competed for sovereignty and land. Others, such as Ancient Egyptians, Hittites, Persians, Babylonians, and the Mongol raids of the late 1200s, were historical 'events' whose successive occupations were as ravaging as the effects of major earthquakes ... Like shooting stars, the various cultures shine for a brief moment before they fade out of official historical and cultural records of Palestine. The people, however, survive. In their customs and manners, fossils of these ancient civilizations survived until modernity—albeit modernity camouflaged under the veneer of Islam and Arabic culture.[90]

George Antonius, founder of modern Arab nationalist history, wrote in his seminal 1938 book The Arab Awakening:

The Arabs' connection with Palestine goes back uninterruptedly to the earliest historic times, for the term 'Arab' [in Palestine] denotes nowadays not merely the incomers from the Arabian Peninsula who occupied the country in the seventh century, but also the older populations who intermarried with their conquerors, acquired their speech, customs and ways of thought and became permanently arabised.[91]

American historian Bernard Lewis writes:

Clearly, in Palestine as elsewhere in the Middle East, the modern inhabitants include among their ancestors those who lived in the country in antiquity. Equally obviously, the demographic mix was greatly modified over the centuries by migration, deportation, immigration, and settlement. This was particularly true in Palestine, where the population was transformed by such events as the Jewish rebellion against Rome and its suppression, the Arab conquest, the coming and going of the Crusaders, the devastation and resettlement of the coastlands by the Mamluk and Turkish regimes, and, from the nineteenth century, by extensive migrations from both within and from outside the region. Through invasion and deportation, and successive changes of rule and of culture, the face of the Palestinian population changed several times. No doubt, the original inhabitants were never entirely obliterated, but in the course of time they were successively Judaized, Christianized, and Islamized. Their language was transformed to Hebrew, then to Aramaic, then to Arabic.[92]

Arabization of Palestine

The term "Arab", as well as the presence of Arabians in the Syrian Desert and the Fertile Crescent, is first seen in the Assyrian sources from the 9th century BCE (Eph'al 1984).[93] Southern Palestine had a large Edomite and Arab population by the 4th century BCE.[94] Inscriptional evidence over a millennium from the peripheral areas of Palestine, such as the Golan and the Negev, show a prevalence of Arab names over Aramaic names from the Achaemenid period,550 -330 BCE onwards.[95][96] Bedouins have drifted in waves into Palestine since at least the 7th century, after the Muslim conquest. Some of them, like the Arab al-Sakhr south of Lake Kinneret trace their origins to the Hejaz or Najd in the Arabian Peninsula, while the Ghazawiyya's ancestry is said to go back to the Hauran's Misl al-Jizel tribes.[97] They speak distinct dialects of Arabic in the Galilee and the Negev.[98]

Following the Muslim conquest of the Levant by the Arab Muslim Rashiduns, the formerly dominant languages of the area, Aramaic and Greek, were gradually replaced by the Arabic language introduced by the new conquering administrative minority.[99] Among the cultural survivals from pre-Islamic times are the significant Palestinian Christian community, roughly 10% of the overall population in late Ottoman times and 45% of Jerusalem's citizens,[100] and smaller Jewish and Samaritan ones, as well as an Aramaic substratum in some local Palestinian Arabic dialects.[101]

The Christians appear to have maintained a majority in much of both Palestine and Syria under Muslim rule until the Crusades. The original conquest in the 630s had guaranteed religious freedom, improving that of the Jews and the Samaritans, who were classified with the former.[102][103][104] The Frankish invaders made no distinction between Christians who for the Latin rite were considered heretics, Jews and Muslims, slaughtering all indiscriminately.[105][106] The Crusaders, in wresting holy sites such as the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem from the Orthodox church were among several factors that deeply alienated the traditional Christian community, which sought relief in the Muslims. When Saladin overthrew the Crusaders, he restored these sites to Orthodox Christian control.[107] Together with the alienating policies of the Crusaders, the Mongol Invasion and the rise of the Mamluks were turning points in the fate of Christianity in this region, and their congregations, -many Christians had sided with the Mongols – were noticeably reduced under the Mamluks. Stricter regulations to control Christian communities ensued, theological enmities grew, and the process of Arabization and Islamicization strengthened, abetted with the inflow of nomadic Bedouin tribes in the 13th and 14th centuries.[108]

Palestinian villagers generally trace their family (hamula)'s origins to the Arabian peninsula. Many avow oral traditions of descent from nomadic Arab tribes that migrated to Palestine during or shortly after the Islamic conquest.[109] By this claim they attempt to connect themselves to the greater narrative of Arab-Islamic civilization, with origins that are more highly valued Arab socio-cultural context than to genealogical descent from local ancient pre-Arab or pre-Islamic peoples. Even so, these Palestinians still consider themselves to have historical precedence to the Jews,[109] whom they regard as Europeans who only began to immigrate to Palestine in the 19th century.

Many Palestinian families of the notable class (a'yan) claim to trace their origins back to tribes in the Arabian peninsula who settled the area after the Muslim conquest.[110] This includes the Nusaybah clan of Jerusalem,[111] the Tamimi clan of Nabi Salih, and the Barghouti clan of Bani Zeid.[112][113] The Shawish, al-Husayni, and Al-Zayadina[114][115] clans trace their heritage to Muhammad through his grandsons, Husayn ibn Ali and Hassan ibn Ali.[116]

Arabs in Palestine, both Christian and Muslim, settled and Bedouin, were historically split between the Qays and Yaman factions.[117] These divisions had their origins in pre-Islamic tribal feuds between Northern Arabians (Qaysis) and Southern Arabians (Yamanis). The strife between the two tribal confederacies spread throughout the Arab world with their conquests, subsuming even uninvolved families so that the population of Palestine identified with one or the other.[117][118] Their conflicts continued after the 8th century Civil war in Palestine until the early 20th century[119] and gave rise to differences in customs, tradition, and dialect which remain to this day.[117]

Beit Sahour was first settled in the 14th century by a handful of Christian and Muslim clans (hamula) from Wadi Musa in Jordan, the Christian Jaraisa and the Muslim Shaybat and Jubran, who came to work as shepherds for Bethlehem's Christian landowners, and they were subsequently joined by other Greek Orthodox immigrants from Egypt in the 17th–18th centuries.[120]

Due to the legacy of the Ottoman period, the ethnic origins of some rural and urban Palestinians are either Albanian, Circassian or from other non-Arab populations.[121]

Canaanism

Claims emanating from certain circles within Palestinian society and their supporters, proposing that Palestinians have direct ancestral connections to the ancient Canaanites, without an intermediate Israelite link, has been an issue of contention within the context of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Bernard Lewis wrote that "the rewriting of the past is usually undertaken to achieve specific political aims ... In bypassing the biblical Israelites and claiming kinship with the Canaanites, the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Palestine, it is possible to assert a historical claim antedating the biblical promise and possession put forward by the Jews."[92][122]

Some Palestinian scholars, like Zakariyya Muhammad, have criticized pro-Palestinian arguments based on Canaanite lineage, or what he calls "Canaanite ideology". He states that it is an "intellectual fad, divorced from the concerns of ordinary people."[123] By assigning its pursuit to the desire to predate Jewish national claims, he describes Canaanism as a "losing ideology", whether or not it is factual, "when used to manage our conflict with the Zionist movement" since Canaanism "concedes a priori the central thesis of Zionism. Namely that we have been engaged in a perennial conflict with Zionism—and hence with the Jewish presence in Palestine—since the Kingdom of Solomon and before ... thus in one stroke Canaanism cancels the assumption that Zionism is a European movement, propelled by modern European contingencies..."[123]

Commenting on the implications of Canaanite ideology, Eric M. Meyers, a Duke University historian of religion, writes:

What is the significance of the Palestinians really being descended from the Canaanites? In the early and more conservative reconstruction of history, it might be said that this merely confirms the historic enmity between Israel and its enemies. However, some scholars believe that Israel actually emerged from within the Canaanite community itself (Northwest Semites) and allied itself with Canaanite elements against the city-states and elites of Canaan. Once they were disenfranchised by these city-states and elites, the Israelites and some disenfranchised Canaanites joined together to challenge the hegemony of the heads of the city-states and forged a new identity in the hill country based on egalitarian principles and a common threat from without. This is another irony in modern politics: the Palestinians in truth are blood brothers or cousins of the modern Israelis — they are all descendants of Abraham and Ishmael, so to speak.[124]

Relationship to the Jewish people

A number of pre-Mandatory Zionists, from Ahad Ha'am and Ber Borochov to David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben Zvi thought of the Palestinian peasant population as descended from the ancient biblical Hebrews, but this belief was disowned when its ideological implications became problematic.[123] Ahad Ha'am believed that, "the Moslems [of Palestine] are the ancient residents of the land ... who became Christians on the rise of Christianity and became Moslems on the arrival of Islam."[123] Israel Belkind, the founder of the Bilu movement also asserted that the Palestinian Arabs were the blood brothers of the Jews.[125] Ber Borochov, one of the key ideological architects of Marxist Zionism, claimed as early as 1905 that, "The Fellahin in Eretz-Israel are the descendants of remnants of the Hebrew agricultural community,"[126] believing them to be descendants of the ancient Hebrew- residents 'together with a small admixture of Arab blood'".[123] He further believed that the Palestinian peasantry would embrace Zionism and that the lack of a crystallized national consciousness among Palestinian Arabs would result in their likely assimilation into the new Hebrew nationalism, and that Arabs and Jews would unite in class struggle.[123][127] David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben Zvi, later becoming Israel's first Prime Minister and second President, respectively, suggested in a 1918 paper written in Yiddish that Palestinian peasants and their mode of life were living historical testimonies to Israelite practices in the biblical period.[123][128] Tamari notes that "the ideological implications of this claim became very problematic and were soon withdrawn from circulation."[123] Salim Tamari notes the paradoxes produced by the search for "nativist" roots among these Zionist figures, particularly the Canaanist followers of Yonatan Ratosh,[123] who sought to replace the "old" diasporic Jewish identity with a nationalism that embraced the existing residents of Palestine.[129]

In his book on the Palestinians, The Arabs in Eretz-Israel, Belkind advanced the idea that the dispersion of Jews out of the Land of Israel after the destruction of the Second Temple by the Roman emperor Titus is a "historic error" that must be corrected. While it dispersed much of the land's Jewish community around the world, those "workers of the land that remained attached to their land," stayed behind and were eventually converted to Christianity and then Islam.[125] He therefore, proposed that this historical wrong be corrected, by embracing the Palestinians as their own and proposed the opening of Hebrew schools for Palestinian Arab Muslims to teach them Arabic, Hebrew and universal culture.[125] Tsvi Misinai, an Israeli researcher, entrepreneur and proponent of a controversial alternative solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, asserts that nearly 90% of all Palestinians living within Israel and the occupied territories (including Israel's Arab citizens and Negev Bedouin)[130] are descended from the Jewish Israelite peasantry that remained on the land, after the others, mostly city dwellers, were exiled or left.[131]

DNA and genetic studies

A study found that the Palestinians, like Jordanians, Syrians, Iraqis, Turks, and Kurds have what appears to be Female-Mediated gene flow in the form of Maternal DNA Haplogroups from Sub-Saharan Africa. Of the 117 Palestinian individuals tested, 15 carried maternal haplogroups that originated in Sub-Saharan Africa. These results are consistent with female migration from eastern Africa into Near Eastern communities within the last few thousand years. There have been many opportunities for such migrations during this period. However, the most likely explanation for the presence of predominantly female lineages of African origin in these areas is that they may trace back to women brought from Africa as part of the Arab slave trade, assimilated into the areas under Arab rule.[132]

In a 2003 genetic study, Bedouins showed the highest rates (62.5%) of the subclade Haplogroup J-M267 among all populations tested, followed by Palestinian Arabs (38.4%), Iraqis (28.2%), Ashkenazi Jews (14.6%) and Sephardic Jews (11.9%), according to Semino et al.[133] Semitic populations usually possess an excess of J1 Y chromosomes compared to other populations harboring Y-haplogroup J.[133][134][135][136][137]

According to a study published in June 2017 by Ranajit Das, Paul Wexler, Mehdi Pirooznia, and Eran Elhaik in Frontiers in Genetics, "in a principle component analysis (PCA) [of DNA], the ancient Levantines clustered predominantly with modern-day Palestinians and Bedouins..."[138] In a study published in August 2017 by Marc Haber et al. in The American Journal of Human Genetics, the authors concluded that "The overlap between the Bronze Age and present-day Levantines suggests a degree of genetic continuity in the region."[139]

A 2013 study by Haber et al. found that "The predominantly Muslim populations of Syrians, Palestinians and Jordanians cluster on branches with other Muslim populations as distant as Morocco and Yemen." The authors explained that "religious affiliation had a strong impact on the genomes of the Levantines. In particular, conversion of the region's populations to Islam appears to have introduced major rearrangements in populations' relations through admixture with culturally similar but geographically remote populations leading to genetic similarities between remarkably distant populations." The study found that Christians and Druzes became genetically isolated following the arrival of Islam. The authors reconstructed the genetic structure of pre-Islamic Levant and found that "it was more genetically similar to Europeans than to Middle Easterners."[140]

In a genetic study of Y-chromosomal STRs in two populations from Israel and the Palestinian Authority Area: Christian and Muslim Palestinians showed genetic differences. The majority of Palestinian Christians (31.82%) were a subclade of E1b1b, followed by G2a (11.36%), and J1 (9.09%). The majority of Palestinian Muslims were haplogroup J1 (37.82%) followed by E1b1b (19.33%), and T (5.88%). The study sample consisted of 44 Palestinian Christians and 119 Palestinian Muslims.[141]

Between the Jews and Palestinians

In recent years, many genetic studies have demonstrated that, at least paternally, most of the various Jewish ethnic divisions and the Palestinians – and other Levantines – are genetically closer to each other than the Jews to their host countries.[142] Many Palestinians themselves referred to their Jewish neighbours as their awlâd 'ammnâ or paternal cousins.[143]

According to a 2010 study by Behar et al. titled "The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people", Palestinians tested clustered genetically close to Bedouins, Jordanians and Saudi Arabians which was described as "consistent with a common origin in the Arabian Peninsula".[144] In the same year a study by Atzmon and Harry Ostrer concluded that the Palestinians were, together with Bedouins, Druze and southern European groups, the closest genetic neighbors to most Jewish populations.[145]

One DNA study by Nebel found substantial genetic overlap among Israeli and Palestinian Arabs and Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews. A small but statistically significant difference was found in the Y-chromosomal haplogroup distributions of Sephardic Jews and Palestinians, but no significant differences were found between Ashkenazi Jews and Palestinians nor between the two Jewish communities. However, a highly distinct cluster was found in Palestinian haplotypes. 32% of the 143 Arab Y-chromosomes studied belonged to this "I&P Arab clade", which contained only one non-Arab chromosome, that of a Sephardic Jew. This could possibly be attributed to the geographical isolation of the Jews or to the immigration of Arab tribes in the first millennium.[146] Nebel proposed that "part, or perhaps the majority" of Muslim Palestinians descend from "local inhabitants, mainly Christians and Jews, who had converted after the Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD".[142]

The haplogroup J1, the ancestor of subclade M267, originates south of the Levant and was first disseminated from there into Ethiopia and Europe in Neolithic times. In Jewish populations, J1 has a rate of around 15%, with haplogroup J2 (M172) (of eight sub-Haplogroups) being almost twice as common as J1 among Jews (<29%). J1 is most common in Palestine, as well as Syria, Iraq, Algeria, and Arabia, and drops sharply at the border of non-semitic areas like Turkey and Iran. A second diffusion of the J1 marker took place in the 7th century CE when Arabians brought it from Arabia to North Africa.[133]

A 2020 study on remains from Canaanaite (Bronze Age southern Levantine) populations suggests a significant degree of genetic continuity in currently Arabic-speaking Levantine populations (including Palestinians, the Lebanese, Druze, and Syrians) as well as in most Jewish groups (including Sephardi Jews, Ashkenazi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, and Maghrebi Jews) from the populations of the Bronze Age Levant, suggesting that the aforementioned groups all derive at least half of their entire atDNA ancestry from Canaanite/Bronze Age Levantine populations,[147][148] albeit with varying sources of admixture from differing host or invading populations depending on each group.

Identity

| Part of a series on |

| Palestinians |

|---|

|

| Demographics |

| Politics |

|

| Religion / religious sites |

| Culture |

| List of Palestinians |

Emergence of a distinct identity

The 20th century historical record reveals an interplay between "Arab" and "Palestinian" identities and nationalism. The idea of a unique Palestinian state distinct from its Arab neighbors was at first rejected by Palestinian representatives. The First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations (in Jerusalem, February 1919), which met for the purpose of selecting a Palestinian Arab representative for the Paris Peace Conference, adopted the following resolution: "We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economic and geographical bonds."[149]

The timing and causes behind the emergence of a distinctively Palestinian national consciousness among the Arabs of Palestine are matters of scholarly disagreement. Some argue that it can be traced as far back as the 1834 Arab revolt in Palestine (or even as early as the 17th century), while others argue that it did not emerge until after the Mandatory Palestine period.[60][150] According to legal historian Assaf Likhovski, the prevailing view is that Palestinian identity originated in the early decades of the 20th century.[60]

Whatever the differing viewpoints over the timing, causal mechanisms, and orientation of Palestinian nationalism (see below), by the early 20th century strong opposition to Zionism and evidence of a burgeoning nationalistic Palestinian identity is found in the content of Arabic-language newspapers in Palestine, such as Al-Karmil (est. 1908) and Filasteen (est. 1911).[151] Filasteen initially focused its critique of Zionism around the failure of the Ottoman administration to control Jewish immigration and the large influx of foreigners, later exploring the impact of Zionist land-purchases on Palestinian peasants (Arabic: فلاحين, fellahin), expressing growing concern over land dispossession and its implications for the society at large.[151]

Historian Rashid Khalidi's 1997 book Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness is considered a "foundational text" on the subject.[152] He notes that the archaeological strata that denote the history of Palestine – encompassing the Biblical, Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Abbasid, Fatimid, Crusader, Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman periods – form part of the identity of the modern-day Palestinian people, as they have come to understand it over the last century.[63] Noting that Palestinian identity has never been an exclusive one, with "Arabism, religion, and local loyalties" playing an important role, Khalidi cautions against the efforts of some extreme advocates of Palestinian nationalism to "anachronistically" read back into history a nationalist consciousness that is in fact "relatively modern".[153][154]

Khalidi argues that the modern national identity of Palestinians has its roots in nationalist discourses that emerged among the peoples of the Ottoman empire in the late 19th century that sharpened following the demarcation of modern nation-state boundaries in the Middle East after World War I.[154] Khalidi also states that although the challenge posed by Zionism played a role in shaping this identity, that "it is a serious mistake to suggest that Palestinian identity emerged mainly as a response to Zionism."[154]

Conversely, historian James L. Gelvin argues that Palestinian nationalism was a direct reaction to Zionism. In his book The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War he states that "Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement."[156] Gelvin argues that this fact does not make the Palestinian identity any less legitimate: "The fact that Palestinian nationalism developed later than Zionism and indeed in response to it does not in any way diminish the legitimacy of Palestinian nationalism or make it less valid than Zionism. All nationalisms arise in opposition to some 'other.' Why else would there be the need to specify who you are? And all nationalisms are defined by what they oppose."[156]

David Seddon writes that "[t]he creation of Palestinian identity in its contemporary sense was formed essentially during the 1960s, with the creation of the Palestine Liberation Organization." He adds, however, that "the existence of a population with a recognizably similar name ('the Philistines') in Biblical times suggests a degree of continuity over a long historical period (much as 'the Israelites' of the Bible suggest a long historical continuity in the same region)."[157]

Baruch Kimmerling and Joel S. Migdal consider the 1834 Peasants' revolt in Palestine as constituting the first formative event of the Palestinian people. From 1516 to 1917, Palestine was ruled by the Ottoman Empire save a decade from the 1830s to the 1840s when an Egyptian vassal of the Ottomans, Muhammad Ali, and his son Ibrahim Pasha successfully broke away from Ottoman leadership and, conquering territory spreading from Egypt to as far north as Damascus, asserted their own rule over the area. The so-called Peasants' Revolt by Palestine's Arabs was precipitated by heavy demands for conscripts. The local leaders and urban notables were unhappy about the loss of traditional privileges, while the peasants were well aware that conscription was little more than a death sentence. Starting in May 1834 the rebels took many cities, among them Jerusalem, Hebron and Nablus and Ibrahim Pasha's army was deployed, defeating the last rebels on 4 August in Hebron.[158] Benny Morris argues that the Arabs in Palestine nevertheless remained part of a larger national pan-Arab or, alternatively, pan-Islamist movement.[159] Walid Khalidi argues otherwise, writing that Palestinians in Ottoman times were "[a]cutely aware of the distinctiveness of Palestinian history ..." and "[a]lthough proud of their Arab heritage and ancestry, the Palestinians considered themselves to be descended not only from Arab conquerors of the seventh century but also from indigenous peoples who had lived in the country since time immemorial, including the ancient Hebrews and the Canaanites before them."[160]

Zachary J. Foster argued in a 2015 Foreign Affairs article that "based on hundreds of manuscripts, Islamic court records, books, magazines, and newspapers from the Ottoman period (1516–1918), it seems that the first Arab to use the term "Palestinian" was Farid Georges Kassab, a Beirut-based Orthodox Christian." He explained further that Kassab's 1909 book Palestine, Hellenism, and Clericalism noted in passing that "the Orthodox Palestinian Ottomans call themselves Arabs, and are in fact Arabs," despite describing the Arabic speakers of Palestine as Palestinians throughout the rest of the book."[161]

Bernard Lewis argues it was not as a Palestinian nation that the Arabs of Ottoman Palestine objected to Zionists, since the very concept of such a nation was unknown to the Arabs of the area at the time and did not come into being until very much later. Even the concept of Arab nationalism in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire, "had not reached significant proportions before the outbreak of World War I."[43] Tamir Sorek, a sociologist, submits that, "Although a distinct Palestinian identity can be traced back at least to the middle of the nineteenth century (Kimmerling and Migdal 1993; Khalidi 1997b), or even to the seventeenth century (Gerber 1998), it was not until after World War I that a broad range of optional political affiliations became relevant for the Arabs of Palestine."[150]

Israeli historian Efraim Karsh takes the view that the Palestinian identity did not develop until after the 1967 war because the Palestinian exodus had fractured society so greatly that it was impossible to piece together a national identity. Between 1948 and 1967, the Jordanians and other Arab countries hosting Arab refugees from Palestine/Israel silenced any expression of Palestinian identity and occupied their lands until Israel's conquests of 1967. The formal annexation of the West Bank by Jordan in 1950, and the subsequent granting of its Palestinian residents Jordanian citizenship, further stunted the growth of a Palestinian national identity by integrating them into Jordanian society.[162]

Rise of Palestinian nationalism

An independent Palestinian state has not exercised full sovereignty over the land in which the Palestinians have lived during the modern era. Palestine was administered by the Ottoman Empire until World War I, and then overseen by the British Mandatory authorities. Israel was established in parts of Palestine in 1948, and in the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the West Bank was ruled by Jordan, and the Gaza Strip by Egypt, with both countries continuing to administer these areas until Israel occupied them in the Six-Day War. Historian Avi Shlaim states that the Palestinians' lack of sovereignty over the land has been used by Israelis to deny Palestinians their rights to self-determination.[163]

Today, the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination has been affirmed by the United Nations General Assembly, the International Court of Justice[164] and several Israeli authorities.[165] A total of 133 countries recognize Palestine as a state.[166] However, Palestinian sovereignty over the areas claimed as part of the Palestinian state remains limited, and the boundaries of the state remain a point of contestation between Palestinians and Israelis.

British Mandate (1917–47)

The first Palestinian nationalist organizations emerged at the end of the World War I.[167] Two political factions emerged. al-Muntada al-Adabi, dominated by the Nashashibi family, militated for the promotion of the Arabic language and culture, for the defense of Islamic values and for an independent Syria and Palestine. In Damascus, al-Nadi al-Arabi, dominated by the Husayni family, defended the same values.[168]

Article 22 of The Covenant of the League of Nations conferred an international legal status upon the territories and people which had ceased to be under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire as part of a 'sacred trust of civilization'. Article 7 of the League of Nations Mandate required the establishment of a new, separate, Palestinian nationality for the inhabitants. This meant that Palestinians did not become British citizens, and that Palestine was not annexed into the British dominions.[169] The Mandate document divided the population into Jewish and non-Jewish, and Britain, the Mandatory Power considered the Palestinian population to be composed of religious, not national, groups. Consequently, government censuses in 1922 and 1931 would categorize Palestinians confessionally as Muslims, Christians and Jews, with the category of Arab absent.[170]

The articles of the Mandate mentioned the civil and religious rights of the non-Jewish communities in Palestine, but not their political status. At the San Remo conference, it was decided to accept the text of those articles, while inserting in the minutes of the conference an undertaking by the Mandatory Power that this would not involve the surrender of any of the rights hitherto enjoyed by the non-Jewish communities in Palestine. In 1922, the British authorities over Mandatory Palestine proposed a draft constitution that would have granted the Palestinian Arabs representation in a Legislative Council on condition that they accept the terms of the mandate. The Palestine Arab delegation rejected the proposal as "wholly unsatisfactory", noting that "the People of Palestine" could not accept the inclusion of the Balfour Declaration in the constitution's preamble as the basis for discussions. They further took issue with the designation of Palestine as a British "colony of the lowest order."[171] The Arabs tried to get the British to offer an Arab legal establishment again roughly ten years later, but to no avail.[172]

After the British general, Louis Bols, read out the Balfour Declaration in February 1920, some 1,500 Palestinians demonstrated in the streets of Jerusalem.[173] A month later, during the 1920 Nebi Musa riots, the protests against British rule and Jewish immigration became violent and Bols banned all demonstrations. In May 1921 however, further anti-Jewish riots broke out in Jaffa and dozens of Arabs and Jews were killed in the confrontations.[173]

After the 1920 Nebi Musa riots, the San Remo conference and the failure of Faisal to establish the Kingdom of Greater Syria, a distinctive form of Palestinian Arab nationalism took root between April and July 1920.[174][175] With the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the French conquest of Syria, coupled with the British conquest and administration of Palestine, the formerly pan-Syrianist mayor of Jerusalem, Musa Qasim Pasha al-Husayni, said "Now, after the recent events in Damascus, we have to effect a complete change in our plans here. Southern Syria no longer exists. We must defend Palestine".[176]

Conflict between Palestinian nationalists and various types of pan-Arabists continued during the British Mandate, but the latter became increasingly marginalized. Two prominent leaders of the Palestinian nationalists were Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, appointed by the British, and Izz ad-Din al-Qassam.[173] After the killing of sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam by the British in 1935, his followers initiated the 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine, which began with a general strike in Jaffa and attacks on Jewish and British installations in Nablus.[173] The Arab Higher Committee called for a nationwide general strike, non-payment of taxes, and the closure of municipal governments, and demanded an end to Jewish immigration and a ban of the sale of land to Jews. By the end of 1936, the movement had become a national revolt, and resistance grew during 1937 and 1938. In response, the British declared martial law, dissolved the Arab High Committee and arrested officials from the Supreme Muslim Council who were behind the revolt. By 1939, 5,000 Arabs had been killed in British attempts to quash the revolt; more than 15,000 were wounded.[173]

War (1947–1949)

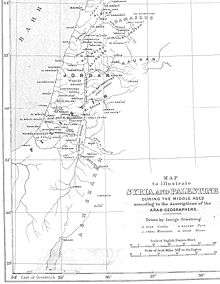

Boundaries defined in the 1947 UN Partition Plan for Palestine:

Armistice Demarcation Lines of 1949 (Green Line):

In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Partition Plan, which divided the mandate of Palestine into two states: one majority Arab and one majority Jewish. The Palestinian Arabs rejected the plan and attacked Jewish civilian areas and paramilitary targets. Following Israel's declaration of independence in May 1948, five Arab armies (Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Transjordan) came to the Palestinian Arabs' aid against the newly founded State of Israel.[177]

The Palestinian Arabs suffered such a major defeat at the end of the war, that the term they use to describe the war is Al Nakba (the "catastrophe").[178] Israel took control of much of the territory that would have been allocated to the Arab state had the Palestinian Arabs accepted the UN partition plan.[177] Along with a military defeat, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled or were expelled from what became the State of Israel. Israel did not allow the Palestinian refugees of the war to return to Israel.[179]

"Lost years" (1949–1967)

After the war, there was a hiatus in Palestinian political activity. Khalidi attributes this to the traumatic events of 1947–49, which included the depopulation of over 400 towns and villages and the creation of hundreds of thousands of refugees.[180] 418 villages had been razed, 46,367 buildings, 123 schools, 1,233 mosques, 8 churches and 68 holy shrines, many with a long history, destroyed by Israeli forces.[181] In addition, Palestinians lost from 1.5 to 2 million acres of land, an estimated 150,000 urban and rural homes, and 23,000 commercial structures such as shops and offices.[182] Recent estimates of the cost to Palestinians in property confiscations by Israel from 1948 onwards has concluded that Palestinians have suffered a net $300 billion loss in assets.[66]

Those parts of British Mandatory Palestine which did not become part of the newly declared Israeli state were occupied by Egypt or annexed by Jordan. At the Jericho Conference on 1 December 1948, 2,000 Palestinian delegates supported a resolution calling for "the unification of Palestine and Transjordan as a step toward full Arab unity".[183] During what Khalidi terms the "lost years" that followed, Palestinians lacked a center of gravity, divided as they were between these countries and others such as Syria, Lebanon, and elsewhere.[184]

In the 1950s, a new generation of Palestinian nationalist groups and movements began to organize clandestinely, stepping out onto the public stage in the 1960s.[185] The traditional Palestinian elite who had dominated negotiations with the British and the Zionists in the Mandate, and who were largely held responsible for the loss of Palestine, were replaced by these new movements whose recruits generally came from poor to middle-class backgrounds and were often students or recent graduates of universities in Cairo, Beirut and Damascus.[185] The potency of the pan-Arabist ideology put forward by Gamal Abdel Nasser—popular among Palestinians for whom Arabism was already an important component of their identity[186]—tended to obscure the identities of the separate Arab states it subsumed.[187]

1967–present

Since 1967, Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip have lived under military occupation, creating, according to Avram Bornstein, a carceralization of their society.[188] In the meantime, pan-Arabism has waned as an aspect of Palestinian identity. The Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and West Bank triggered a second Palestinian exodus and fractured Palestinian political and militant groups, prompting them to give up residual hopes in pan-Arabism. They rallied increasingly around the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which had been formed in Cairo in 1964. The group grew in popularity in the following years, especially under the nationalistic orientation of the leadership of Yasser Arafat.[189] Mainstream secular Palestinian nationalism was grouped together under the umbrella of the PLO whose constituent organizations include Fatah and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, among other groups who at that time believed that political violence was the only way to "liberate" Palestine.[63] These groups gave voice to a tradition that emerged in the 1960s that argues Palestinian nationalism has deep historical roots, with extreme advocates reading a Palestinian nationalist consciousness and identity back into the history of Palestine over the past few centuries, and even millennia, when such a consciousness is in fact relatively modern.[190]

The Battle of Karameh and the events of Black September in Jordan contributed to growing Palestinian support for these groups, particularly among Palestinians in exile. Concurrently, among Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, a new ideological theme, known as sumud, represented the Palestinian political strategy popularly adopted from 1967 onward. As a concept closely related to the land, agriculture and indigenousness, the ideal image of the Palestinian put forward at this time was that of the peasant (in Arabic, fellah) who stayed put on his land, refusing to leave. A strategy more passive than that adopted by the Palestinian fedayeen, sumud provided an important subtext to the narrative of the fighters, "in symbolizing continuity and connections with the land, with peasantry and a rural way of life."[191]

In 1974, the PLO was recognized as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people by the Arab nation-states and was granted observer status as a national liberation movement by the United Nations that same year.[64][192] Israel rejected the resolution, calling it "shameful".[193] In a speech to the Knesset, Deputy Premier and Foreign Minister Yigal Allon outlined the government's view that: "No one can expect us to recognize the terrorist organization called the PLO as representing the Palestinians—because it does not. No one can expect us to negotiate with the heads of terror-gangs, who through their ideology and actions, endeavor to liquidate the State of Israel."[193]

In 1975, the United Nations established a subsidiary organ, the Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People, to recommend a program of implementation to enable the Palestinian people to exercise national independence and their rights to self-determination without external interference, national independence and sovereignty, and to return to their homes and property.[194]

The First Intifada (1987–93) was the first popular uprising against the Israeli occupation of 1967. Followed by the PLO's 1988 proclamation of a State of Palestine, these developments served to further reinforce the Palestinian national identity. After the Gulf War in 1991, Kuwaiti authorities forcibly pressured nearly 200,000 Palestinians to leave Kuwait.[195] The policy which partly led to this exodus was a response to the alignment of PLO leader Yasser Arafat with Saddam Hussein.

The Oslo Accords, the first Israeli–Palestinian interim peace agreement, were signed in 1993. The process was envisioned to last five years, ending in June 1999, when the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the Gaza Strip and the Jericho area began. The expiration of this term without the recognition by Israel of the Palestinian State and without the effective termination of the occupation was followed by the Second Intifada in 2000.[196][197] The second intifada was more violent than the first.[198] The International Court of Justice observed that since the government of Israel had decided to recognize the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people, their existence was no longer an issue. The court noted that the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip of 28 September 1995 also referred a number of times to the Palestinian people and its "legitimate rights".[199] According to Thomas Giegerich, with respect to the Palestinian people's right to form a sovereign independent state, "The right of self-determination gives the Palestinian people collectively the inalienable right freely to determine its political status, while Israel, having recognized the Palestinians as a separate people, is obliged to promote and respect this right in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations".[200]

Following the failures of the Second Intifada, a younger generation is emerging that cares less about nationalist ideology than in economic growth. This has been a source of tension between some of Palestinians political leadership and Palestinian business professionals who desire economic cooperation with Israelis. At an international conference in Bahrain, Palestinian businessman Ashraf Jabari said, “I have no problem working with Israel. It is time to move on. ... The Palestinian Authority does not want peace. They told the families of the businessmen that they are wanted [by police] for participating in the Bahrain workshop.”[201]

Demographics

| Country or region | Population |

|---|---|

| Palestinian Territories (Gaza Strip and West Bank including East Jerusalem) | 4,420,549[3] |

| Jordan | 2,700,000[202] |

| Israel | 1,318,000[203] |

| Chile | 500,000 (largest community outside the Middle East)[204][205][206] |

| Syria | 434,896[207] |

| Lebanon | 405,425[207] |

| Saudi Arabia | 327,000[203] |

| The Americas | 225,000[208] |

| Egypt | 44,200[208] |

| Kuwait | (approx) 40,000[203] |

| Other Gulf states | 159,000[203] |

| Other Arab states | 153,000[203] |

| Other countries | 308,000[203] |

| TOTAL | 10,574,521 |

In the absence of a comprehensive census including all Palestinian diaspora populations, and those that have remained within what was British Mandate Palestine, exact population figures are difficult to determine. The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) announced at the end of 2015 that the number of Palestinians worldwide at the end of 2015 was 12.37 million of which the number still residing within historic Palestine was 6.22 million.[209]

In 2005, a critical review of the PCBS figures and methodology was conducted by the American-Israel Demographic Research Group (AIDRG).[210] In their report,[211] they claimed that several errors in the PCBS methodology and assumptions artificially inflated the numbers by a total of 1.3 million. The PCBS numbers were cross-checked against a variety of other sources (e.g., asserted birth rates based on fertility rate assumptions for a given year were checked against Palestinian Ministry of Health figures as well as Ministry of Education school enrollment figures six years later; immigration numbers were checked against numbers collected at border crossings, etc.). The errors claimed in their analysis included: birth rate errors (308,000), immigration & emigration errors (310,000), failure to account for migration to Israel (105,000), double-counting Jerusalem Arabs (210,000), counting former residents now living abroad (325,000) and other discrepancies (82,000). The results of their research was also presented before the United States House of Representatives on 8 March 2006.[212]

The study was criticised by Sergio DellaPergola, a demographer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[213] DellaPergola accused the authors of the AIDRG report of misunderstanding basic principles of demography on account of their lack of expertise in the subject, but he also acknowledged that he did not take into account the emigration of Palestinians and thinks it has to be examined, as well as the birth and mortality statistics of the Palestinian Authority.[214] He also accused AIDRG of selective use of data and multiple systematic errors in their analysis, claiming that the authors assumed the Palestinian Electoral registry to be complete even though registration is voluntary, and they used an unrealistically low Total Fertility Ratio (a statistical abstraction of births per woman) to reanalyse that data in a "typical circular mistake." DellaPergola estimated the Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza at the end of 2005 as 3.33 million, or 3.57 million if East Jerusalem is included. These figures are only slightly lower than the official Palestinian figures.[213] The Israeli Civil Administration put the number of Palestinians in the West Bank at 2,657,029 as of May 2012.[215][216]

The AIDRG study was also criticized by Ian Lustick, who accused its authors of multiple methodological errors and a political agenda.[217]

In 2009, at the request of the PLO, "Jordan revoked the citizenship of thousands of Palestinians to keep them from remaining permanently in the country."[218]

Many Palestinians have settled in the United States, particularly in the Chicago area.[219][220]

In total, an estimated 600,000 Palestinians are thought to reside in the Americas. Palestinian emigration to South America began for economic reasons that pre-dated the Arab-Israeli conflict, but continued to grow thereafter.[221] Many emigrants were from the Bethlehem area. Those emigrating to Latin America were mainly Christian. Half of those of Palestinian origin in Latin America live in Chile.[11] El Salvador[222] and Honduras[223] also have substantial Palestinian populations. These two countries have had presidents of Palestinian ancestry (Antonio Saca in El Salvador and Carlos Roberto Flores in Honduras). Belize, which has a smaller Palestinian population, has a Palestinian minister – Said Musa.[224] Schafik Jorge Handal, Salvadoran politician and former guerrilla leader, was the son of Palestinian immigrants.[225]

Refugees

In 2006, there were 4,255,120 Palestinians registered as refugees with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). This number includes the descendants of refugees who fled or were expelled during the 1948 war, but excludes those who have since then emigrated to areas outside of UNRWA's remit.[207] Based on these figures, almost half of all Palestinians are registered refugees. The 993,818 Palestinian refugees in the Gaza Strip and 705,207 Palestinian refugees in the West Bank, who hail from towns and villages now located within the borders of Israel, are included in these figures.[226]

UNRWA figures do not include some 274,000 people, or 1 in 5.5 of all Arab residents of Israel, who are internally displaced Palestinian refugees.[227][228]

Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and the West Bank are organized according to a refugee family's village or place of origin. Among the first things that children born in the camps learn is the name of their village of origin. David McDowall writes that, "[...] a yearning for Palestine permeates the whole refugee community and is most ardently espoused by the younger refugees, for whom home exists only in the imagination."[229]

Israeli policy to prevent the refugees returning to their homes was initially formulated by David Ben Gurion and Joseph Weitz, director of the Jewish National Fund was formally adopted by the Israeli cabinet in June 1948.[230] In December of that year the UN adopted resolution 194, which resolved "that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible."[231][232][233] Despite much of the international community, including the US President Harry Truman, insisting that the repatriation of Palestinian refugees was essential, Israel refused to accept the principle.[233] In the intervening years Israel has consistently refused to change its position and has introduced further legislation to hinder Palestinians refugees from returning and reclaiming their land and confiscated property.[232][233]

In keeping with an Arab League resolution in 1965, most Arab countries have refused to grant citizenship to Palestinians, arguing that it would be a threat to their right of return to their homes in Palestine.[232][234] In 2012, Egypt deviated from this practice by granting citizenship to 50,000 Palestinians, mostly from the Gaza Strip.[234]

Palestinians living in Lebanon are deprived of basic civil rights. They cannot own homes or land, and are barred from becoming lawyers, engineers and doctors.[235]

Religion

A majority of Palestinians are Muslim,[237] the vast majority of whom are followers of the Sunni branch of Islam,[238] with a small minority of Ahmadiyya.[239] Palestinian Christians represent a significant minority of 6%, followed by much smaller religious communities, including Druze and Samaritans. Palestinian Jews – considered Palestinian by the Palestinian National Charter adopted by the PLO which defined them as those "Jews who had normally resided in Palestine until the beginning of the Zionist invasion" – today identify as Israelis[240] (with the exception of a very few individuals). Palestinian Jews almost universally abandoned any such identity after the establishment of Israel and their incorporation into the Israeli Jewish population, largely composed of Jewish immigrants from around the world.

Until the end of the 19th century, most Palestinian Muslim villagers in the countryside did not have local mosques. Cross-cultural syncretism between Christian and Islamic symbols and figures in religious practice was common.[90] Popular feast days, like Thursday of the Dead, were celebrated by both Muslims and Christians and shared prophets and saints include Jonah, who is venerated in Halhul as both a Biblical and Islamic prophet, and St. George, who is known in Arabic as el Khader. Villagers would pay tribute to local patron saints at a maqam – a domed single room often placed in the shadow of an ancient carob or oak tree.[90] Saints, taboo by the standards of orthodox Islam, mediated between man and Allah, and shrines to saints and holy men dotted the Palestinian landscape.[90] Ali Qleibo, a Palestinian anthropologist, states that this built evidence constitutes "an architectural testimony to Christian/Moslem Palestinian religious sensibility and its roots in ancient Semitic religions."[90]

Religion as constitutive of individual identity was accorded a minor role within Palestinian tribal social structure until the latter half of the 19th century.[90] Jean Moretain, a priest writing in 1848, wrote that a Christian in Palestine was "distinguished only by the fact that he belonged to a particular clan. If a certain tribe was Christian, then an individual would be Christian, but without knowledge of what distinguished his faith from that of a Muslim."[90]

The concessions granted to France and other Western powers by the Ottoman Sultanate in the aftermath of the Crimean War had a significant impact on contemporary Palestinian religious cultural identity.[90] Religion was transformed into an element "constituting the individual/collective identity in conformity with orthodox precepts", and formed a major building block in the political development of Palestinian nationalism.[90]

The British census of 1922 registered 752,048 inhabitants in Palestine, consisting of 660,641 Palestinian Arabs (Christian and Muslim Arabs), 83,790 Palestinian Jews, and 7,617 persons belonging to other groups. The corresponding percentage breakdown is 87% Christian and Muslim Arab and 11% Jewish. Bedouin were not counted in the census, but a 1930 British study estimated their number at 70,860.[241]

Bernard Sabella of Bethlehem University estimates that 6% of the Palestinian population worldwide is Christian and that 56% of them live outside of historic Palestine.[242] According to the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, the Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza Strip is 97% Muslim and 3% Christian. The vast majority of the Palestinian community in Chile follow Christianity, largely Orthodox Christian and some Roman Catholic, and in fact the number of Palestinian Christians in the diaspora in Chile alone exceeds the number of those who have remained in their homeland.[243]

The Druze became Israeli citizens and Druze males serve in the Israel Defense Forces, though some individuals identify as "Palestinian Druze".[244] According to Salih al-Shaykh, most Druze do not consider themselves to be Palestinian: "their Arab identity emanates in the main from the common language and their socio-cultural background, but is detached from any national political conception. It is not directed at Arab countries or Arab nationality or the Palestinian people, and does not express sharing any fate with them. From this point of view, their identity is Israel, and this identity is stronger than their Arab identity".[245]

There are also about 350 Samaritans who carry Palestinian identity cards and live in the West Bank while a roughly equal number live in Holon and carry Israeli citizenship.[246] Those who live in the West Bank also are represented in the legislature for the Palestinian National Authority.[246] They are commonly referred to among Palestinians as the "Jews of Palestine," and maintain their own unique cultural identity.[246]

Jews who identify as Palestinian Jews are few, but include Israeli Jews who are part of the Neturei Karta group,[247] and Uri Davis, an Israeli citizen and self-described Palestinian Jew (who converted to Islam in 2008 in order to marry Miyassar Abu Ali) who serves as an observer member in the Palestine National Council.[248]

Bahá'u'lláh, founder of the Baha'i Faith, was from Iran, but ended his life in Acre, Israel, then part of the Ottoman Empire. He was confined there for 24 years. A shrine has been erected there in his honor.[249][250]

Palestinians attending prayers at the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem

Palestinians attending prayers at the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem- The Church of the Holy Sepulchre located in Jerusalem, is one of the most sacred places to Palestinian Christians.

Palestinian Christian Scouts on Christmas Eve in front of the Nativity Church in Bethlehem, 2006

Palestinian Christian Scouts on Christmas Eve in front of the Nativity Church in Bethlehem, 2006 Jews in 'Ben Zakai' house of prayer, Jerusalem, 1893.

Jews in 'Ben Zakai' house of prayer, Jerusalem, 1893.

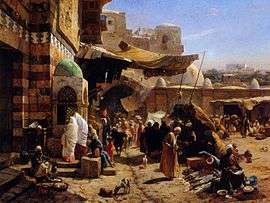

Muslims pray in Jerusalem, 1840. By David Roberts, in The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia

Muslims pray in Jerusalem, 1840. By David Roberts, in The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia

Current demographics

According to the PCBS, there are an estimated 4,816,503 Palestinians in the Palestinian territories as of 2016, of whom 2,935,368 live in the West Bank and 1,881,135 in the Gaza Strip.[3] According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, there were 1,658,000 Arab citizens of Israel as of 2013.[251] Both figures include Palestinians in East Jerusalem.

In 2008, Minority Rights Group International estimated the number of Palestinians in Jordan to be about 3 million.[252] The UNRWA put their number at 2.1 million as of December 2015.[54]

Society

Language

Palestinian Arabic is a subgroup of the broader Levantine Arabic dialect. Prior to the 7th century Islamic Conquest and Arabization of the Levant, the primary languages spoken in Palestine, among the predominantly Christian and Jewish communities, were Aramaic, Greek, and Syriac.[253] Arabic was also spoken in some areas.[254] Palestinian Arabic, like other variations of the Levantine dialect, exhibits substantial influences in lexicon from Aramaic.[255]

Palestinian Arabic has three primary sub-variations, Rural, Urban, and Bedouin, with the pronunciation of the Qāf serving as a shibboleth to distinguish between the three main Palestinian sub-dialects: The urban variety notes a [Q] sound, while the rural variety (spoken in the villages around major cities) have a [K] for the [Q]. The Bedouin variety of Palestine (spoken mainly in the southern region and along the Jordan valley) use a [G] instead of [Q].[256]

Barbara McKean Parmenter has noted that the Arabs of Palestine have been credited with the preservation of the original Semitic place names of many sites mentioned in the Bible, as was documented by the American geographer Edward Robinson in the 19th century.[257]

Palestinians who live or work in Israel generally can also speak Modern Hebrew, as do some who live in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Education

The literacy rate of Palestine was 96.3% according to a 2014 report by the United Nations Development Programme, which is high by international standards. There is a gender difference in the population aged above 15 with 5.9% of women considered illiterate compared to 1.6% of men.[258] Illiteracy among women has fallen from 20.3% in 1997 to less than 6% in 2014.[258]

Palestinian intellectuals, among them May Ziadeh and Khalil Beidas, were an integral part of the Arab intelligentsia. Educational levels among Palestinians have traditionally been high. In the 1960s the West Bank had a higher percentage of its adolescent population enrolled in high school education than did Lebanon.[259] Claude Cheysson, France's Minister for Foreign Affairs under the first Mitterrand Presidency, held in the mid eighties that, ‘even thirty years ago, (Palestinians) probably already had the largest educated elite of all the Arab peoples.’[260]

Contributions to Palestinian culture have been made by diaspora figures like Edward Said and Ghada Karmi, Arab citizens of Israel like Emile Habibi, and Jordanians like Ibrahim Nasrallah.[261][262]

.jpg) Palestinian students and John Kerry

Palestinian students and John Kerry Palestinian students

Palestinian students Palestinian students

Palestinian students

Women and family

In the 19th and early 20th century, there were some well known Palestinian families, which included the Khalidi family, the al-Husayni clan, the Nashashibi clan, the Tuqan clan, the Nusaybah clan, Qudwa family, Shawish clan, Shurrab family, Al-Zaghab family, Al-Khalil family, Ridwan dynasty, Al-Zeitawi family, Abu Ghosh clan, Barghouti clan, Doghmush clan, Douaihy family, Hilles clan, Jarrar clan, and the Jayyusi clan. Since various conflicts with Zionists began, some of the communities have subsequently left Palestine. The role of women varies among Palestinians, with both progressive and ultra-conservative opinions existing. Other groups of Palestinians, such as the Negev Bedouins or Druze may no longer self-identify as Palestinian for political reasons.[263]

Culture

Ali Qleibo, a Palestinian anthropologist, has critiqued Muslim historiography for assigning the beginning of Palestinian cultural identity to the advent of Islam in the 7th century. In describing the effect of such a historiography, he writes:

Pagan origins are disavowed. As such the peoples who populated Palestine throughout history have discursively rescinded their own history and religion as they adopted the religion, language, and culture of Islam.[90]

That the peasant culture of the large fellahin class showed features of cultures other than Islam was a conclusion arrived at by some Western scholars and explorers who mapped and surveyed Palestine during the latter half of the 19th century,[264] and these ideas were to influence 20th century debates on Palestinian identity by local and international ethnographers. The contributions of the 'nativist' ethnographies produced by Tawfiq Canaan and other Palestinian writers and published in The Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society (1920–48) were driven by the concern that the "native culture of Palestine", and in particular peasant society, was being undermined by the forces of modernity.[123] Salim Tamari writes that:

Implicit in their scholarship (and made explicit by Canaan himself) was another theme, namely that the peasants of Palestine represent—through their folk norms ... the living heritage of all the accumulated ancient cultures that had appeared in Palestine (principally the Canaanite, Philistine, Hebraic, Nabatean, Syrio-Aramaic and Arab).[123]

Palestinian culture is closely related to those of the nearby Levantine countries such as Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, and the Arab World. Cultural contributions to the fields of art, literature, music, costume and cuisine express the characteristics of the Palestinian experience and show signs of common origin despite the geographical separation between the Palestinian territories, Israel and the diaspora.[265][266][267]

Al-Quds Capital of Arab Culture is an initiative undertaken by UNESCO under the Cultural Capitals Program to promote Arab culture and encourage cooperation in the Arab region. The opening event was launched in March 2009.

Palestinian women

Palestinian women_(7556004512).jpg) Palestinian children

Palestinian children

Cuisine

Palestine's history of rule by many different empires is reflected in Palestinian cuisine, which has benefited from various cultural contributions and exchanges. Generally speaking, modern Syrian-Palestinian dishes have been influenced by the rule of three major Islamic groups: the Arabs, the Persian-influenced Arabs and the Turks.[268] The Arabs who conquered Syria and Palestine had simple culinary traditions primarily based on the use of rice, lamb and yogurt, as well as dates.[269] The already simple cuisine did not advance for centuries due to Islam's strict rules of parsimony and restraint, until the rise of the Abbasids, who established Baghdad as their capital. Baghdad was historically located on Persian soil and henceforth, Persian culture was integrated into Arab culture during the 9th–11th centuries and spread throughout central areas of the empire.[268]

There are several foods native to Palestine that are well known in the Arab world, such as, kinafe Nabulsi, Nabulsi cheese (cheese of Nablus), Ackawi cheese (cheese of Acre) and musakhan. Kinafe originated in Nablus, as well as the sweetened Nabulsi cheese used to fill it. Another very popular food is Palestinian Kofta or Kufta.[270]

Mezze describes an assortment of dishes laid out on the table for a meal that takes place over several hours, a characteristic common to Mediterranean cultures. Some common mezze dishes are hummus, tabouleh,baba ghanoush, labaneh, and zate 'u zaatar, which is the pita bread dipping of olive oil and ground thyme and sesame seeds.[271]

Entrées that are eaten throughout the Palestinian territories, include waraq al-'inib – boiled grape leaves wrapped around cooked rice and ground lamb. Mahashi is an assortment of stuffed vegetables such as, zucchinis, potatoes, cabbage and in Gaza, chard.[272]

Art

Similar to the structure of Palestinian society, the Palestinian field of arts extends over four main geographic centers: the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Israel, the Palestinian diaspora in the Arab world, and the Palestinian diaspora in Europe, the United States and elsewhere.[273]

- Cinema

Palestinian cinematography, relatively young compared to Arab cinema overall, receives much European and Israeli support.[274] Palestinian films are not exclusively produced in Arabic; some are made in English, French or Hebrew.[275] More than 800 films have been produced about Palestinians, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and other related topics. Examples include Divine Intervention and Paradise Now.

The Alhamra Cinema, Jaffa, 1937, bombed December 1947

The Alhamra Cinema, Jaffa, 1937, bombed December 1947 Villagers in Halhul at an open-air cinema screening c. 1940

Villagers in Halhul at an open-air cinema screening c. 1940

- Handicrafts

A wide variety of handicrafts, many of which have been produced in the area of Palestine for hundreds of years, continue to be produced today. Palestinian handicrafts include embroidery and weaving, pottery-making, soap-making, glass-making, and olive-wood and Mother of Pearl carvings, among others.[276][277]

- Costumes

Foreign travelers to Palestine in late 19th and early 20th centuries often commented on the rich variety of costumes among the area's inhabitants, and particularly among the fellaheen or village women. Until the 1940s, a woman's economic status, whether married or single, and the town or area they were from could be deciphered by most Palestinian women by the type of cloth, colors, cut, and embroidery motifs, or lack thereof, used for the robe-like dress or "thoub" in Arabic.[278]