Mappila

Mappila, also known as a Mappila Muslim, formerly anglicized as Moplah/Mopla and historically known as Jonaka/Chonaka Mappila or Moors Mopulars/Mouros da Terra and Mouros Malabares, in general, is a member of the Muslim community of the same name found predominantly in Kerala, southern India.[1][2] Mappilas share the common language of Malayalam with the other communities of Kerala.[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

In terms of Ihsan |

|

|

|

Lists |

|

|

According to some scholars, the Mappilas are the oldest settled native Muslim community in South Asia.[1] In general, a Mappila is either a descendant of any native convert to Islam or a mixed descendant of any Middle Eastern — Arab or non Arab — individual. Mappilas are but one among the many communities that forms the Muslim population of Kerala. No Census Report where the Muslim communities were mentioned separately is also available. As per some scholars, the term "Mappila" denotes not a single community but a variety of Malayali Muslims from north Kerala (Malabar District) of different origins. In south Kerala Malayali Muslims are not called Mappilas.[4]

The Mappila community originated primarily as a result of the West Asian contacts with Kerala, which was fundamentally based upon commerce ("the spice trade").[2] As per local tradition, Islam reached Malabar Coast, of which the Kerala state is a part of, as early as the 7th century AD. Before being overtaken by the Europeans in the spice trade, Mappilas were a prosperous trading community, settled mainly in the coastal urban centres of Kerala. The continuous interaction of the Mappilas with the Middle East have created a profound impact on their life, customs and culture. This has resulted in the formation of a unique Indo-Islamic synthesis — within the large spectrum of Kerala culture — in literature, art, food, language, and music.[3]

Most of the Muslims in Kerala follow the Shāfiʿī School, while a large minority follow modern movements that developed within Sunni Islam.[3][5]

Etymology

Mappilas are but one among the many communities that forms the Muslim population of Kerala. Sometimes the whole Muslim community in former Malabar District, or even in Kerala, is known by the term "Mappila". Portuguese writer Duarte Barbosa (1515) uses the term 'Moors Mopulars' for the Muslims of Kerala.

"Mappila" ("the great child", a synonym for son-in-law[1]/bridegroom[3]) was a respectful, and honorific title given to foreign visitors, merchants and immigrants to Malabar Coast by the native Hindus.[3] The Muslims were referred to as Jonaka or Chonaka Mappila ("Yavanaka Mappila"), to distinguish them from the Nasrani Mappila (Saint Thomas Christians) and the Juda Mappila (Cochin Jews). [6]

Demographics and distribution

Distribution

Aside from Kerala, Mappilas are found in the Laccadive Islands in the Arabian Sea.[3] A small number of Malayali Muslims have settled in the southern districts of Karnataka and western parts of Tamil Nadu, while the scattered presence of the community in major cities of India can also be seen. When the British supremacy on Malabar District was established, many Mappilas were recruited for employment in plantations in Burma, Assam and for manual labor in South East Asian concerns of the British Empire. Diaspora groups of Mappilas are also found in Pakistan and Malaysia.[3] Furthermore, a substantial proportion of Muslims have left Kerala to seek employment in the Middle East, especially in Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates.

British distinctions

During the British period the so-called Mappila Outbreaks, c. 1836–1921 led the officials to make and maintain a distinction between the southern (South Malabar) interior Mappilas and the 'respectable' Mappila traders of the coastal cities, such as Calicut (North Malabar). The two other regional groupings are the high-status Muslim families of Cannanore in North Malabar — arguably converts from high caste Hindus — and the Muslims of Travancore and Cochin.[7] In South Kerala Malayali Muslims are not called (presently) Mappilas. The Colonial administrates also kept a distinction between coastal and inland Mappilas of the South Malabar.[3][7]

- Tangals (the Sayyids) - at the top were the aristrocratic Tangals (the Sayyids), who claim descent from the family of Prophet Muhammed (West Asian descent).[8]

- Arabis - Below the Tangals are Arabis (mostly from the coastal towns), the people tracing their origin from the West Asian intermarriage with Malayali women.[8]

- Landed Aristocracy - the Arabis were followed by the landed aristocracy, centred on Cannanore, North Malabar.[7]

- Lastly, there were the converts from the Backward and Scheduled Hindu castes (such as the South Malabar interior Mappilas, Pusalars/Puyislans and the Ossans).[7]

History

The European period

Initially (c. 1500–1520), Portuguese traders were successful in reaching in agreements with the local Hindu chiefs and native Muslim (Mappila) merchants in Kerala. The major contradiction was between the Portuguese state and the Arab and Persian traders, and the Kingdom of Calicut. The big Mappila traders in Cochin supplied large quantities of Southeast Asian spices to the Portuguese carracks. These traders, along with the Syrian Christians, acted as brokers and intermediaries in the purchase of spices and in the sale of the goods brought from Europe.[9][10]

Wealthy Muslim merchants of the Malabar Coast - including Mappilas - provided large credits to the Portuguese. These businessmen received large trading concessions, stipends and privileges in return. Interaction between the Portuguese private traders and Mappila merchants also continued to be tolerated by the Portuguese state. Kingdom of Calicut, whose shipping was increasingly looted by the Portuguese, evolved into a centre of Muslim resistance.[4]

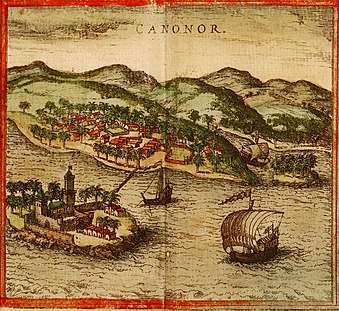

Sooner rather than later, tensions arose between the wealthy Mappila traders of Cannanore and the Portuguese state. The ships of the Cannanore Mappilas again and again fell prey to the Portuguese sailors off the coast of Maldives, an important point between Southeast Asia and the Red Sea. Interests of the Portuguese casado moradores in Cochin, now planning to capture the spice trade through the Gulf of Mannar and to Sri Lanka, came into the conflict with Mappilas and the (Tamil) Maraikkayars. The narrow gulf held the key to the trade to Bengal (especially Chittagong). By 1520s, open confrontations between the Portuguese and the Mappilas, from Ramanathapuram, and Thoothukudi to northern Kerala, and to western Sri Lanka, became a common occurrence.[9] The Mappila traders actively worked in even in the island of Sri Lanka to oppose the Portuguese. The Portuguese maintained patrolling squadrons off the Kerala ports and continued their raids on departing Muslim fleets at Calicut and Quilon.[10] After a series of naval battles, the once powerful Mappila chief was finally forced to sue for peace with the Portuguese in 1540. The peace was soon broken, with the assassination of the qazi of Cannanore Abu Bakr Ali (1545), and the Portuguese again came down hard on the Mappilas. In the meantime, the Portuguese also entered into friendship with some of the leading Middle Eastern merchants residing on the Malabar Coast (1550). The mantle of the Muslim resistance was now taken by the Ali Rajas of Cannanore, who even forced the king of Calicut to turn against the Portuguese once again.[9] By the close of the 16th century, the Ali Rajas had emerged as figures with as much influence in Kerala as the Kolathiri (Chirakkal Raja) himself.[10]

.jpg)

Before the 16th century, Middle Eastern Muslims dominated the economic, social and religious affairs of Kerala Muslims. Many of these merchants fled Kerala in the course of the 16th century. The vacuum created economic opportunities for some Mappila traders, who also took on a greater role in the social and religious affairs in Malabar.[4] The Portuguese tried to establish a monopoly in the spice trade in India, using violent naval warfare.[11][12] Whenever a formal war was broke out between the Portuguese and the Calicut rulers, the Portuguese attacked and plundered, as the opportunity offered, the Muslim ports in Kerala. Small, lightly armed, and highly mobile vessels of the Mappilas remained a major threat to Portuguese shipping all along the west coast of India.[9][10] Mappila merchants, now controlling pepper trade in Calicut in the place of the West Asian Muslims, drew Mappila corsairs and used them to transport the spices past Portuguese blockades. Some Mappila traders even tried to outwit the Portuguese by reorienting their trade to Western Indian ports. Some chose an overland route, across the Western Ghats, for the export of spices.[4] By the end of the 16th century, the Portuguese were finally able to deal with the "Mappila challenge". Kunjali Marakkar was defeated and killed, with the help of the Calicut ruler, in c. 1600 AD. The Ali Rajas of Cannanore was given permission to send ships to even to the Red Sea, as a way of ensuring their cooperation.[9] The relentless battles led to the eventual decline of the Muslim community in Kerala, as they gradually lost control of the spice trade. The Muslims — who had been depended solely on commerce — were reduced into severe economic perplexity. Some traders turned inland (South Malabar) in search of alternate occupations to commerce. The Muslims of Kerala gradually became a society of small traders, landless labourers and poor fishermen. The once affluent, and urban, Muslim population became predominantly rural in Kerala.[3][7]

Kingdom of Mysore, ruled by Muslim sultan Haider Ali, invaded and occupied northern Kerala in the late-18th century.[13] In the following Mysore rule of Malabar, Muslims were favoured against the high caste Hindu landlords. Some were able to obtain some land rights and administrative positions. There was a sharp increase in community's growth, especially through conversions from the "outcaste" society. However, such measures of the Mysore rulers only widened the communal imbalance of Malabar. The East India Company — taking advantage of the situation — allied with the Hindu high castes to fight against the occupied regime. The British subsequently won the Anglo-Mysore War against Mysore ruler Tipu Sultan and, consequently, Malabar was organised as a district under Madras Presidency.[14]

The discriminatory land tenure system — tracing its origins to pre modern Kerala — gave Muslims of Kerala (and other tenants and labourers) no access to land ownership.[1] The partisan rule of British authorities brought the Mappila peasants of Malabar District into a condition of destitution. This led to a series of violent attacks against the high caste landlords and British administration (the Mappila Outbreaks, c. 1836–1921[7]) and in 1921–22; it took in the form of an explosion known as Mappila Uprising (Malabar Rebellion).[14][15] The uprising — which at least started as an Indian nationalistic movement and then absorbed most of the negative elements in the Malabarian society — was brutally suppressed by the colonial government, leaving the Muslim community in further despair, poverty and illiteracy.[3]

Culture

Mappila literature

Mappila Songs/Poems is a famous folklore tradition emerged in c. 16th century. The ballads are compiled in complex blend of Malayalam/Tamil and Arabic, Persian/Urdu in a modified Arabic script.[16] Mappila songs have a distinct cultural identity, as they sound a mix of the ethos and culture of Dravidian South India as well as West Asia. They deal with themes such as romance, satire, religion, and politics. Moyinkutty Vaidyar (1875–91) is generally considered as the poet laureate of Mappila Songs.[3]

As the modern Mappila literature developed after the 1921–22 Uprising, religious publications dominated the field.[3]

Vaikom Muhammad Basheer (1910–1994), followed by, U. A. Khader, K. T. Muhammed, N. P. Muhammed and Moidu Padiyath are leading Mappila authors of the modern age. Mappila periodical literature and newspaper dailies — all in Malayalam — are also extensive and critically read among the Muslims. The newspaper known as "Chandrika", founded in 1934, played as significant role in the development of the Mappila community.[3]

Mappila folk arts

- Oppana was a popular form of social entertainment among the Muslims of Kerala. It is generally presented by women numbering about fifteen including musicians, as a part of wedding ceremonies a day before the wedding day. The bride, dressed in all finery, covered with gold ornaments, is the chief spectator; she sits on a peetham, around which the singing and dancing take place. While women sing, they clap their hands rhythmically and move around the bride in steps. Two or three girls begin the songs and the rest join the chorus.

- Kolkkali was a popular dance form among the Muslims of Kerala. It is played in group of 12 people with two sticks, similar to the Dandiya dance of Gujarat.

- Duff Muttu[17] (also called Dubh Muttu) was an art form prevalent among Muslims of Kerala, using the traditional duff, or daf, also known as tappitta. Participants dance to the rhythm as they beat the duff.

.jpg) Anonymous 16th-century Portuguese illustration from Códice Casanatense, depicting Kerala Muslims ("Mouros Malabares")

Anonymous 16th-century Portuguese illustration from Códice Casanatense, depicting Kerala Muslims ("Mouros Malabares") Mappilas captured after a battle with British colonial troops, during 1921-22 Uprising.

Mappilas captured after a battle with British colonial troops, during 1921-22 Uprising. Mappila prisoners of 1921-22 Uprising go to trial at Calicut

Mappila prisoners of 1921-22 Uprising go to trial at Calicut.jpg) Mappila man and woman from Kerala

Mappila man and woman from Kerala.jpg) Mappila man in Malabar (1926-1933)

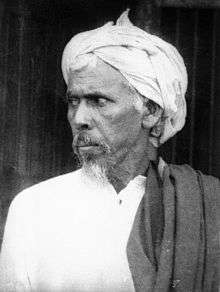

Mappila man in Malabar (1926-1933) Ali Musliyar, the rebel leader of the Mappila Uprising (1921-22), shortly before his execution in Coimbatore.

Ali Musliyar, the rebel leader of the Mappila Uprising (1921-22), shortly before his execution in Coimbatore.

References

- Miller, Roland E. Mappila Muslim Culture. State University of New York Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-1-4384-5601-0.

- Panikkar, K. N. (1989). Against Lord and State: Religion and Peasant Uprisings in Malabar 1836–1921. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19562-139-6.

- Miller, Roland E. (1988). "Mappila". The Encyclopedia of Islam. VI. E. J. Brill. pp. 458–66.

- Prange, Sebastian R. (2018). Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press.

- "Kerala Public Service Commission". Home 2. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Mathur, P. R. G. "The Mappila Fisherfolk of Kerala: a Study in Inter-relationship Between Habitat, Technology, Economy, Society, and Culture" (1977), Anthropological Survey of India, Kerala Historical Society, p. 1.

- Nossiter, Thomas J. (1982). Communism in Kerala: A Study in Political Adaptation. C. Hurst and Company. pp. 23–25.

- Jeffrey, Robin (1992). Politics, Women and Well Being: How Kerala Became 'a Model'. Palgrave McMillan. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-333-54808-0.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2012). The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500-1700: A Political and Economic History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-47067-291-4.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2002). The Political Economy of Commerce: Southern India 1500-1650. Cambridge University Press.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1998). The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama. Cambridge University Press. pp. 293–294. ISBN 978-0-521-64629-1.

- Shokoohy, Mehrdad (2003). Muslim Architecture of South India: The Sultanate of Ma'bar and the Traditions of the Maritime Settlers on the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts (Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Goa). Psychology Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-415-30207-4.

- Elgood, Robert (1995). Firearms of the Islamic World: in the Tared Rajab Museum, Kuwait. I. B. Tauris. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-1-85043-963-9.

- Kurien, Prema A. (2002). Kaleidoscopic Ethnicity: International Migration and the Reconstruction of Community Identities in India. Rutgers University Press. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-0-8135-3089-5.

- "Moplahs a Menace for Several Years — Malabar Fanatics Said to Have Been Emboldened by Shifting of British Troops" (PDF). The New York Times. 4 September 1921.

- "Preserve identity of Mappila songs". Chennai, India: The Hindu. 7 May 2006. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- "Madikeri, Coorg, "Gaddige Mohiyadeen Ratib" Islamic religious "dikr" is held once in a year". YouTube. Retrieved 17 February 2012.