Baggara

The Baggāra (Arabic: بقَّارة "cattle herder"[5]) are a grouping of Arab ethnic groups inhabiting the portion of Africa's Sahel mainly between Lake Chad and southern Kordofan, numbering over six million.[6] They are known as Baggara in Sudan,[7] and as Shuwa/Diffa Arabs in Chad and Nigeria.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Numbering over 6 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| at least 3 million in Darfur[1] | |

| at least 2,391,000[2] | |

| 303,000[3] | |

| 171,000 | |

| 150,000 Diffa Arabs in Diffa Region[4] | |

| 107,000 | |

| unknown | |

| Languages | |

| Chadian Arabic, Sudanese Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam (Sufi-oriented) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Arabs (Sudanese, Bedouin groups, Juhaynah), Nubians and Chadians | |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Baggāra. |

The Baggāra mostly speak Chadian Arabic, with the exception of those in South Kordofan, who speak Sudanese Arabic. They also have a common traditional mode of subsistence, nomadic cattle herding, although nowadays many lead a settled existence. Nevertheless, collectively they do not all necessarily consider themselves one people, i.e., a single ethnic group. The term "baggara culture" was introduced in 1994 by Braukämper.[5]

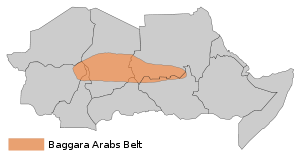

The political use of the term baggāra in Sudan denoting a particular set of tribes is limited to Sudan. It often means a coalition of majority Arabs and a few indigenous African tribes, mainly the Fur people, Nuba peoples and Fula people, with other Arab tribes of western Sudan, mainly the Juhaynah, as opposed to Bedouin Abbala tribes. The bulk of "baggara Arabs" live in Chad, the rest live, or seasonally migrate to, southwest Sudan (specifically the southern portions of Darfur and Kordofan), and slivers of the Central African Republic, South Sudan, and Niger. Those who are still nomads migrate seasonally between grazing lands in the wet season and river areas in the dry season.

Their common language is known to academics by various names, such as Chadian Arabic, taken from the regions where the language is spoken. For much of the 20th century, this language was known to academics as "Shuwa Arabic", but "Shuwa" is a geographically and socially parochial term that has fallen into disuse among linguists specializing in the language, who instead refer to it as "Chadian Arabic" depending on the origin of the native speakers being consulted for a given academic project.

Origins and divisions

The origin of the Baggara is determined. According to a MacMichael, the group arrived in Wadai between Bornu and Darfur, where they spread from 1635 onwards through the fusion of the Arabic speaking population with the indigenous groups. Like other Arabic speaking tribes in the Sahara and the Sahel, Baggara tribes have origin ancestry from the Juhaynah Arab tribes who migrated directly from the Arabian peninsula or from other parts of north Africa. [8]

Baggara tribes in Sudan include: the Rizeigat, Ta’isha, Beni Halba, and Habbaniya in Darfur, and the Messiria Zurug, Messiria Humur, Hawazma, and Awlad Himayd in Kordofan, and the Beni Selam on the White Nile. For complete and accurate account about Baggara tribes, see: Baggara of Sudan: Culture and Environment. The Misseiria of Jebel Mun speak a Nilo-Saharan language, Miisiirii, related to the Tama of their traditional neighbors.

The small community of "Baggara Arabs" in the southeastern corner of Niger is known as Diffa Arabs for the Diffa Region. They occupy the shore of Lake Chad and migrated from Nigeria since World War II. Most of the Diffa Arabs claim descent from the Mahamid clan of Sudan and Chad.[9]

History

The Baggara of Darfur and Kordofan were the backbone of the Mahdist revolt against Turko-Egyptian rule in Sudan in the 1880s. The Mahdi's second-in-command, the Khalifa Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, was himself a Baggara of the Ta'aisha tribe. During the Mahdist period (1883–98) tens of thousands of Baggara migrated to Omdurman and central Sudan where they provided many of the troops for the Mahdist armies.

After their defeat at the Battle of Karari in 1898, the remnants returned home to Darfur and Kordofan. Under the British system of indirect rule, each of the major Baggara tribes was ruled by its own paramount chief (nazir). Most of them were loyal members of the Umma Party, headed since the 1960s by Sadiq el Mahdi.

The main Baggara tribes of Darfur were awarded "hawakir" (land grants) by the Fur Sultans in the 1750s. As a result, the four largest Baggara tribes of Darfur—the Rizeigat, Habbaniya, Beni Halba and Ta’isha—have been only marginally involved in the Darfur conflict. However, the Baggara have been deeply involved in other conflicts in both Sudan and Chad. Starting in 1985, the Government of Sudan armed many of the local tribes among them the Rizeigat of south Darfur and the Messiria and Hawazma of neighboring Kordofan as militia to fight a proxy war against the Sudan People's Liberation Army in their areas. They formed frontline units as well as Murahleen, mounted raiders that attacked southern villages to loot valuables and slaves. [10]

The Baggara people (and subgroups) were armed by the Sudanese government to participate in the counterinsurgency against the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army. The first attacks against villages by the Baggara were staged in the Nuba Mountains. The Sudanese government promoted attacks by promising the Baggara people no interference so they could seize animals and land. They formed the precursors to the Janjaweed - an infamous para-military.[11]

During the Second Sudanese Civil War thousands of Dinka women and children were abducted and subsequently enslaved by members of the Missiriya and Rezeigat tribes. An unknown number of children from the Nuba tribe were similarly abducted and enslaved.[12] In Darfur, a Beni Halba militia force was organized by the government to defeat an SPLA force led by Daud Bolad in 1990-91. However, by the mid-1990s the various Baggara groups had mostly negotiated local truces with the SPLA forces. The leaders of the major Baggara tribes declared that they had no interest in joining the fighting.

See also

References

- "Although the most recent census, conducted in 2008, puts Darfur’s popu- lation at 7.5 million, the NCP of President Omar al Bashir insisted that tribe and religion be omitted from the database, reportedly for fear that Sudan would no longer be defined as an Arab, Islamic state. Estimates of the Arab population of Darfur range from 30 per cent, based on the census of 1956, to the 70 per cent claimed by Arab tribal leaders in a letter to United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in September 2007. Given that many Arabs from Chad have settled in Darfur in the last several decades, and that the rate of migration to Sudan’s more developed centre is higher among non-Arabs, who are less dependent on pastoralism, a figure of 40 per cent is probably closer to the mark."

- https://joshuaproject.net/countries/CD, cumulative total of Arab communities

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-11-20. Retrieved 2015-12-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Africa | Niger's Arabs to fight expulsion". BBC News. 2006-10-25. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- Owens 1993, p. 11.

- Baggara of Sudan: Culture and Environment - Culture, Traditions and Livelihood by Biraima M Adam

- Adam, Biraima M. 2012, p. 17.

- deWaal and Flint 2006, pp. 9.

- DeCalco 1979, pp. 31, 179.

- International Crisis Group 2007, p. 2.

- Flint, J. and Alex de Waal, 2008 (2nd Edn), Darfur: A new History of a Long War, Zed Books.

- United States Department of State, 2008

Notes

- James DeCalco. 1979. Historical Dictionary of Niger. Metuchen, NJ & London: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810812290.

- de Waal, Alex and Julie Flint. 2006. Darfur: A Short History of a Long War. London: Zed Books. ISBN 1-84277-697-5.

- International Crisis Group. 2007-10-12. Sudan: breaking the Abyei deadlock.

- Owens, Jonathan. 1993. A grammar of Nigerian Arabic. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. Series: Semitica viva; 10.

- Owens, Jonathan. 2003. Arabic dialect history and historical linguistic mythology. Journal of the American Oriental Society.

- Scheinfeldt, Laura B, et al. 2010. Working toward a synthesis of archaeological, linguistic, and genetic data for inferring African population history. In John C. Avise and Francisco J. Ayala, eds., In the light of evolution. Volume IV: the human condition. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. Series: Arthur M. Sackler Colloquia

- United States Department of State. 2008-06-04. Trafficking in Persons Report 2008—Sudan.

- Adam, Biraima M. 2012. Baggara of Sudan: Culture and Environment, Amazon online Books Baggara of Sudan: Culture and Environment.

Further reading

- Braukämper, Ulrich. 1994. Notes on the origin of Baggara Arab culture with special reference to the Shuwa. In Jonathan Owens, ed., Arabs and Arabic in the Lake Chad Region. Rüdiger Köppe. Series SUGIA (Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika); 14.