Boko Haram insurgency

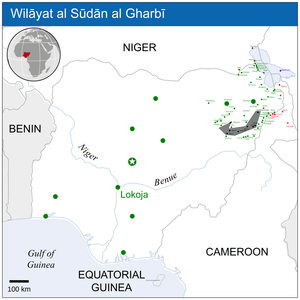

The Boko Haram insurgency began in 2009,[71] when the jihadist group Boko Haram started an armed rebellion against the government of Nigeria.[72] The conflict takes place within the context of long-standing issues of religious violence between Nigeria's Muslim and Christian communities, and the insurgents' ultimate aim is to establish an Islamic state in the region.

| Boko Haram insurgency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Religious violence in Nigeria and the Military intervention against ISIL | |||||||

Niger Army soldiers during an operation against Boko Haram in March 2015 (top) Nigerian CJTF militiamen in 2015 (bottom) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Multinational Joint Task Force Local militias and vigilantes[5] |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Nigerian Army: Militias and vigilantes: Unknown, several tens of thousands[55]

|

2014: Thousands[lower-alpha 3] 2015: 4,000–10,000[57][58] (overall) 2017: c. 5,000 (ISIL loyalists, Barnawi faction)[57] c. 1,000 (Shekau faction)[57] 2018: c. 3,000 (ISIL loyalists, Barnawi faction)[59] c. 1,000 (Shekau faction)[60] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown |

1,957+ killed 1,713+ surrendered[61][62][63][64][65][66] | ||||||

|

51,567+ total killed[67] | |||||||

Boko Haram's initial uprising failed, and its leader Mohammed Yusuf was killed by the Nigerian government. The movement consequently fractured into autonomous groups and started an insurgency, though rebel commander Abubakar Shekau managed to achieve a kind of primacy among the insurgents. Though challenged by internal rivals, such as Abu Usmatul al-Ansari's Salafist conservative faction and the Ansaru faction, Shekau became the insurgency's de facto leader and mostly kept the different Boko Haram factions from fighting each other, instead focusing on overthrowing the Nigerian government. Supported by other jihadist organizations including al-Qaeda and al-Shabaab, Shekau's tactics were marked by extreme brutality and explicit targeting of civilians.

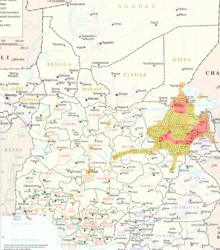

After years of fighting, the insurgents became increasingly aggressive, and started to seize large areas in northeastern Nigeria. The violence escalated dramatically in 2014, with 10,849 deaths, while Boko Haram drastically expanded its territories.[73][74][75][76] At the same time, the insurgency spread to neighboring Cameroon, Chad, and Niger, thus becoming a major regional conflict. Meanwhile, Shekau attempted to improve his international standing among Jihadists by tacitly aligning with the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in March 2015, with Boko Haram becoming the "Islamic State's West Africa Province" (ISWAP).

The insurgents were driven back during the 2015 West African offensive by a Nigeria-led coalition of African and Western states, forcing the Islamists to retreat into Sambisa Forest and bases at Lake Chad. Discontent about various issues consequently grew among Boko Haram. Dissidents among the movement allied themselves with ISIL's central command and challenged Shekau's leadership, resulting in a violent split of the insurgents. Since then, Shekau and his group are generally referred to as "Boko Haram", whereas the dissidents continued to operate as ISWAP under Abu Musab al-Barnawi. The two factions consequently fought against each other while waging insurgencies against the local governments. After a period of reversals, Boko Haram and ISWAP launched new offensives in 2018 and 2019, again growing in strength.

When Boko Haram's insurgency was at its peak in the mid-2010s, it was called the world's deadliest terrorist group, in terms of the number of people it killed.[77][78][79]

Background

Nigerian statehood

Nigeria was amalgamated both the Northern and Southern protectorate in 1914, only about a decade after the defeat of the Sokoto Caliphate and other Islamic states by the British which were to constitute much of Northern Nigeria. Sir Frederick Lugard assumed office as governor of both protectorates in 1912. The aftermath of the First World War saw Germany lose its colonies, one of which was Cameroon, to French, Belgian and British mandates. Cameroon was divided in French and British parts, the latter of which was further subdivided into southern and northern parts. Following a plebiscite in 1961, the Southern Cameroons elected to rejoin French Cameroon, while the Northern Cameroons opted to join Nigeria, a move which added to Nigeria's already large Northern Muslim population.[80] The territory made up much of what is now Northeastern Nigeria, and a large part of the areas affected by the insurgency.

Early religious conflict in Nigeria

Religious conflict in Nigeria dates as far back as 1953. The Igbo massacre of 1966 in the North that followed the counter-coup of the same year had as a dual cause the Igbo officers' coup and pre-existing (sectarian) tensions between the Igbos and the local Muslims. This was a major factor in the Biafran secession and the resulting civil war.

Maitatsine

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was a major Islamic uprising led by Maitatsine (Mohammed Marwa) and his followers, Yan Tatsine that led to several thousand deaths. After Maitatsine's death in 1980, the movement continued some five years more.

In the same decade the erstwhile military ruler of Nigeria, General Ibrahim Babangida enrolled Nigeria in the Organisation of the Islamic Conference. This was a move which aggravated religious tensions in the country, particularly among the Christian community.[81] In response, some in the Muslim community pointed out that certain other African member states have smaller proportions of Muslims, as well as Nigeria's diplomatic relations with the Holy See.

Establishment of Sharia

Since the return of democracy to Nigeria in 1999, Sharia has been instituted as a main body of civil and criminal law in 9 Muslim-majority and in some parts of 3 Muslim-plurality states, when then-Zamfara State governor Ahmad Rufai Sani[83] began the push for the institution of Sharia at the state level of government. This was followed by controversy as to the would-be legal status of the non-Muslims in the Sharia system. A spate of Muslim-Christian riots soon emerged.

In the primarily Islamic northern states of Nigeria, a variety of Muslim groups and populations exist, who favour the nationwide introduction of Sharia Law.[84] The demands of these populations have been at least partially upheld by the Nigerian Federal Government in 12 states, firstly in Zamfara State in 1999. The implementation has been widely attributed as being due to the insistence of Zamfara State governor Ahmad Rufai Sani.[83]

The death sentences of Amina Lawal and Safiya Hussaini attracted international attention to what many saw as the harsh regime of these laws. These sentences were later overturned;[85] the first execution was carried out in 2002.[85]

Blasphemy and apostasy

Twelve out of Nigeria's thirty-six states have Sunni Islam as the dominant religion. In 1999, those states chose to have Sharia courts as well as Customary courts.[86] A Sharia court may treat blasphemy as deserving of several punishments up to, and including, execution.[87][88] In many predominantly Muslim states, conversion from Islam to another religion is illegal and often a capital offence.[89]

Demographic balance

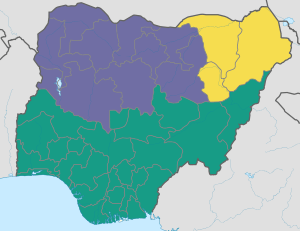

According to a Nigerian study on demographics and religion, Muslims make up 50.5% of the population. Muslims mainly live in the north of the country; the majority of the Nigerian Muslims are Sunnis. Christians are the second-largest religious group and make up 48.2% of the population. They predominate in the central and southern part of the country.[90]

For reasons of avoiding political controversy, questions of religion were forgone in the 2006 Nigerian census.[91][92]

History

2009 Boko Haram uprising

Boko Haram conducted its operations more or less peacefully during the first seven years of its existence.[93] That changed in 2009 when the Nigerian government launched an investigation into the group's activities following reports that its members were arming themselves.[94] Prior to that the government reportedly repeatedly ignored warnings about the increasingly militant character of the organisation, including that of a military officer.[94]

When the government came into action, several members of the group were arrested in Bauchi, sparking deadly clashes with Nigerian security forces in Bauchi, Maiduguri, Potiskum and Wudil which led to the deaths of an estimated 700 people. During the fighting with the security forces Boko Haram fighters reportedly "used fuel-laden motorcycles" and "bows with poison arrows" to attack a police station.[72] The group's founder and then leader Mohammed Yusuf was also killed during this time while still in police custody.[95][96][97] After Yusuf's killing, Abubakar Shekau became the leader and held this position in January 2015.[98]

2010 resurgence

After the killing of M. Yusuf, the group carried out its first terrorist attack in Borno in January 2010. It resulted in the killing of four people.[99] Since then, the violence has only escalated in terms of both frequency and intensity. In September 2010, a Bauchi prison break freed more than 700 Boko Haram militants, replenishing their force.

2011

On 29 May 2011, a few hours after Goodluck Jonathan was sworn in as president, several bombings purportedly by Boko Haram killed 15 and injured 55. On 16 June 2011, Boko Haram claimed to have conducted the Abuja police headquarters bombing, the first known suicide attack in Nigeria. Two months later the United Nations building in Abuja was bombed, signifying the first time that Boko Haram attacked an international organisation. In December 2011, it carried out attacks in Damaturu killing over a hundred people, subsequently clashing with security forces in December, resulting in at least 68 deaths. Two days later on Christmas Day, Boko Haram attacked several Christian churches with bomb blasts and shootings.

15 June 2011 also marked the start of a Federal Government sanctioned military effort to counter the growing threat of Boko Haram's insurgency. With 21 Armoured Brigade (21 Bde) of the Nigerian Army as its nucleus, Joint Task Force Operation Restore Order (JTF ORO 1) marked the start of the Army's lengthy counter-insurgency (COIN) campaign against Boko Haram. The campaign has gone through several phases and has greatly escalated in scale, capacity, components and stakeholders, since that time.[100] Results, however, have sometimes been mixed and the Army has been criticised for being too kinetic in its COIN.

2012

In January 2012, Abubakar Shekau, a former deputy to Yusuf, appeared in a video posted on YouTube. According to Reuters, Shekau took control of the group after Yusuf's death in 2009.[101] Authorities had previously believed that Shekau died during the violence in 2009.[102] By early 2012, the group was responsible for over 900 deaths.[103] On 8 March 2012, a small Special Boat Service team and the Nigerian Army attempted to rescue two hostages, Chris McManus and Franco Lamolinara, being held in Nigeria by members of the Boko Haram terrorist organisation loyal to al-Qaeda. The two hostages were killed before or during the rescue attempt. All the hostage takers were reportedly killed.[104]

2013 government offensive

In May 2013, Nigerian government forces launched an offensive in the Borno region in an attempt to dislodge Boko Haram fighters after a state of emergency was called on 14 May 2013. The state of emergency, which was still in force in May 2014, applied to the states of Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa in northeastern Nigeria.[105] The offensive had initial success, but the Boko Haram rebels were able to regain their strength. In July 2013, Boko Haram massacred 42 students in Yobe,[106] bringing the school year to an early end in the state. On 5 August 2013, Boko Haram launched dual attacks on Bama and Malam Fatori, leaving 35 dead.[107] On 11 August, BH killed 44 people in a mass shooting at a mosque in Konduga, Borno State.[108]

2014 Chibok kidnapping

On 15 April 2014, terrorists abducted about 276 female students from a college in Chibok in Borno state.[109] The abduction was widely attributed to Boko Haram.[110] It was reported that the group had taken the girls to neighbouring Cameroon and Chad where they were to be sold into marriages at a price below a Dollar. The abduction of another eight girls was also reported later. These kidnappings raised public protests, with some protesters holding placards bearing the Twitter tag #BringBackOurGirls which had caught international attention.[111] The Guardian reported that the British Royal Air Force conducted Operation Turus in response the Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping by Boko Haram in Nigeria in April 2014. A source involved with the Operation told The Observer that "The girls were located in the first few weeks of the RAF mission", and that "We [RAF] offered to rescue them, but the Nigerian government declined", this was because it viewed any action to be taken as a "national issue", and for it to be resolved by Nigerian intelligence and security services, the source added that the girls were then tracked by the aircraft as they were dispersed into progressively smaller groups over the following months.[112] Several countries pledged support to the Nigerian government and to help their military with intelligence gathering on the whereabouts of the girls and the operational camps of Boko Haram.

2014 Jos bombings

On 20 May 2014, a total of two bombs in the city of Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria, were detonated, resulting in the deaths of at least 118 people and the injury of more than 56 others. The bombs detonated 30 minutes apart, one at a local market place at approximately 3:00 and the second in a parking lot next to a hospital at approximately 3:30, where rescuers responding to the first accident were killed.[113] Though no group or individual has claimed responsibility, the attacks have been attributed to Boko Haram.[114]

First responders were unable to reach the scenes of the accidents, as "thousands of people were fleeing the scene in the opposite direction". The bombs had been positioned to kill as many people as possible, regardless of religion, which differed from previous attacks in which non-Muslims were targeted. The bombers were reported to have used a "back-to-back blast" tactic, in which an initial bomb explodes at a central location and another explodes a short time later with intent to kill rescue workers working to rescue the wounded.[115]

Escalation in fighting

Starting in late 2014, Boko Haram militants attacked several Nigerian towns in the North and captured them. This prompted the Nigerian government to launch an offensive, and with the help of Chad, Niger, and Cameroon, they have recaptured many areas that were formerly under the control of Boko Haram.[116][117]

In late 2014, Boko Haram seized control of Bama, according to the town's residents.[118] In December 2014, it was reported that "people too elderly to flee Gwoza Local Government Area were being rounded up and taken to two schools where the militants opened fire on them." Over 50 elderly people in Bama were killed.[119] A "gory" video was released of insurgents shooting over a hundred civilians in a school dormitory in the town of Bama.[120]

Between 3 and 7 January 2015, Boko Haram attacked the town of Baga and killed up to 2,000 people,[121] perhaps the largest massacre by Boko Haram.[122]

On 10 January 2015, a bomb attack took place at the Monday Market in Maiduguri, killing 19 people. The city is considered to be at the heart of the Boko Haram insurgency.[123] In the early hours of 25 January 2015, Boko Haram launched a major assault on the city.[124] On 26 January 2015, CNN reported that the attack on Maiduguri by "hundreds of gunmen" had been repelled, but the nearby town of Monguno was captured by Boko Haram.[125] The Nigerian Army claimed to have successfully repelled another attack on Maiduguri on 31 January 2015.[126]

2015 counter-offensive against Boko Haram

On 10 January 2015, 19 people were killed in a suicide bombing in Maiduguri.[127] Starting in late January 2015, a coalition of military forces from Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, and Niger began a counter-insurgency campaign against Boko Haram.[128] On 4 February 2015, the Chad Army killed over 200 Boko Haram militants.[129] Soon afterwards, Boko Haram launched an attack on the Cameroonian town of Fotokol, killing 81 civilians, 13 Chadian soldiers and 6 Cameroonian soldiers.[130] On 17 February 2015, the Nigerian military retook Monguno in a coordinated air and ground assault.[131]

On 7 March 2015, Boko Haram's leader Abubakar Shekau pledged allegiance to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) via an audio message posted on the organisation's Twitter account.[33][132][133] Nigerian army spokesperson Sami Usman Kukasheka said the pledge was a sign of weakness and that Shekau was like a "drowning man".[134] That same day, five suicide bomb blasts left 54 dead and 143 wounded.[135] On 12 March 2015, ISIL's spokesman Abu Mohammad al-Adnani released an audiotape in which he welcomed the pledge of allegiance, and described it as an expansion of the group's caliphate to West Africa.[136]

Following its declaration of loyalty to ISIL, Boko Haram was designated as the group's "West Africa Province" (Islamic State West Africa Province, or ISWAP) while Shekau was appointed as its first vali (governor). Furthermore, ISIL started to support Boko Haram, but also began to interfere in its internal matters. For example, ISIL's central leadership attempted to reduce Boko Haram's brutality toward civilians and internal critics, as Shekau's ideology was "too extreme even for the Islamic State".[32]

On 24 March 2015, residents of Damasak, Nigeria said that Boko Haram had taken more than 400 women and children from the town as they fled from coalition forces.[137] On 27 March 2015, the Nigerian army captured Gwoza, which was believed to be the location of Boko Haram headquarters.[138] On election day, 28 March 2015, Boko Haram extremists killed 41 people, including a legislator, to discourage hundreds from voting.[139]

In March 2015, Boko Haram lost control of the Northern Nigerian towns of Bama[140] and Gwoza (believed to be their headquarters)[141] to the Nigerian army. The Nigerian authorities said that they had taken back 11 of the 14 districts previously controlled by Boko Haram.[140] In April 2016, four Boko Haram camps in the Sambisa Forest were overrun by the Nigerian military who freed nearly 300 females.[142] Boko Haram forces were believed to have retreated to the Mandara Mountains, along the Cameroon–Nigeria border.[143] On 16 March 2015, the Nigerian army said that it had recaptured Bama.[144] On 27 March 2015, the day before the Nigerian presidential election, the Nigerian Army announced that it had recaptured the town of Gwoza from Boko Haram.[145]

By April 2015, the Nigerian military was reported to have retaken most of the areas previously controlled by Boko Haram in Northeastern Nigeria, except for the Sambisa Forest.[146]

In May 2015, the Nigerian military announced that they had released about 700 women from camps in Sambisa Forest.[147][148]

In August 2015, it was reported that over one thousand deaths had occurred since the inauguration of the new administration.[149]

On 28 October 2015, it was announced that Nigerian troops have rescued 338 people from Boko Haram near the group's Sambisa Forest stronghold. Of those rescued, 192 were children and 138 were women.[150]

In December 2015, Muhammadu Buhari, the President of Nigeria, claimed that Boko Haram was "technically defeated"[77] and it was reported that 1,000 women had been rescued from Boko Haram in January 2016.[151][152]

American military support

In early October 2015, the US military deployed 300 troops to Cameroon, with the approval of the Cameroonian government, with the primary mission of providing intelligence support to local forces, and conducting reconnaissance flights.[27][28]

The troops are also overseeing a program to transfer American military vehicles to the Cameroonian Army to aid in their fight against Islamist militants.[153]

As of May 2016, U.S. personnel are involved in drone operations from Garoua to help provide intelligence in the region to assist local forces. There are additional drone operations based out of Niger.[154] U.S. Army soldiers in Cameroon are also providing IED awareness training to the country's infantry forces.[155]

2016

On 25 January, a quadruple suicide bombing killed over 30 people in Bodo, Far North Region, Cameroon.[156]

In March, Boko Haram was reported to have used islands in Lake Chad as bases.[157]

As Boko Haram's power waned, Shekau's leadership was increasingly criticised among Boko Haram and ISIL's central command. These elements repeatedly attempted to convince Shekau to change his tactics or his extreme ideas (such as considering everyone an apostate who has not openly sided with him, including all Muslims). Shekau refused to budge, and openly disobeyed ISIL's "Caliph" Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in regard to various matters. ISIL and parts of Boko Haram eventually came to the conclusion that this was no longer tolerable, whereupon Shekau was removed from his position as vali of ISIL's West Africa Province in August 2016. Abu Musab al-Barnawi, a son of Boko Haram founder Mohammed Yusuf was appointed as his successor. This event resulted in an open split among the Nigerian insurgents. Shekau refused to accept his dismissal, rallied a large number of supporters and violently opposed Barnawi and ISIL's central command. In turn, Barnawi and those who were loyal to him declared Shekau's group Khawarij.[32] The two insurgent factions subsequently became fully separate organizations, with Shekau's followers re-adopting their old name "Jamā'at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da'wah wa'l-Jihād" (outsiders refer to this faction as "Boko Haram"), whereas Barnawi's forces continued to operate as "Islamic State's West Africa Province" (ISWAP). The two groups are generally hostile and fight each other, though it is possible that they occasionally cooperate against their common enemies.[158]

On 31 August, Major General Lucky Irabor stated that the militants now only controlled a few villages and towns near Lake Chad and in Sambisa forest. He further stated that the military expected recapturing the final strongholds of the group within weeks.[159]

On 24 December, President Muhammadu Buhari declared that Boko Haram had been ousted from their last stronghold in the Sambisa Forest, effectively reducing Boko Haram to an insurgent force.[160][161][162] This victory left Boko Haram without any territorial holdings; however, Boko Haram still maintains an extensive ability to carry out attacks.[163]

2017

On 7 January 2017, a group of Boko Haram militants attacked a Nigerian army base in Yobe State, killing five soldiers. In response, the Nigerian Army launched retaliatory strikes and killed 15 militants.[164]

On 17 January 2017, a Nigerian Air Force jet accidentally bombed a refugee camp near the Cameroonian border in Rann, Borno State, mistaking it for a Boko Haram encampment.[165][166][167] The airstrike left 115 people dead.[168]

On 18 March 2017, at least six people were killed and 16 wounded after four female suicide bombers blew themselves up on the outskirts of Maiduguri city.[169]

On 22 March 2017, the Nigerian Department of State Services (DSS) announced that a suspected member of Boko Haram had been arrested in northeastern Yobe State. The suspect confessed details of a plot to attack the American and British embassies, and other western targets in Abuja. The DSS also later announced that between 25 and 26 March 2017, five suspected members of Boko Haram had been arrested, thus thwarting the plot.[170]

On 2 April 2017, the Nigerian military began what it said was its "final offensive" to retake Boko Haram's last strongholds.[171]

On 17 May 2017, the Nigerian Army reported that it had arrested about 126 suspected Boko Haram terrorists at the Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) camp in Damboa, Borno State.[172]

In September 2017, Boko Haram militants kidnapped about 40 young adults, women and children and killed 18 in the town of Banki, 130 km southeast of Maiduguri, Borno State, on the border of Nigeria and Cameroon.[173] Boko Haram was reported to have killed 380 people between April and September 2017 in the Lake Chad area .[173] About 57% of all schools in Borno state were closed due to the Boko Haram insurgency, affecting the education of about 3 million children.[174]

In December 2017, fighters who were believed to belong to ISWAP attacked a patrol of US Army Special Forces and Nigerian soldiers in the Lake Chad Basin Region in Niger. The coalition troops managed to repel the assault without suffering any casualties.[175][176]

2018

By March 2018, two main insurgent factions were still active, and continued to wage an insurgency campaign against the government: The followers of Abubakar Shekau (Boko Haram) operated mainly in southern Borno State, while the faction of Abu Musab al-Barnawi (ISWAP) was mostly located around Lake Chad.[38]

On 26 April 2018, Boko Haram bombers killed at least four civilians in the outskirts of Maiduguri, the largest city in Borno State. A subsequent gun battle and tear gas launched by security forces repelled the attackers, but left two officers wounded and several others injured.[177]

On 15 July 2018, hundreds of Nigerian soldiers went missing after ISWAP forces led by Abu Musab al-Barnawi overran a Nigerian army base in the northeastern part of Nigeria. Less than 100 Nigerian soldiers returned after the attack, the attack came 24 hours after ISIL ambushed a military convoy in the neighboring Borno state. The attack on the base resulted in a battle that lasted over an hour, it is unknown if there were any casualties in the assault, a local pro-government militia said the military had sustained some casualties, this attack marks Boko Haram's first major gain since 2015.[178]

On 8 September 2018, ISWAP fighters managed to capture the town of Gudumbali in central Borno, marking their first major gain in nearly two years.[179] The next day, ISIL's West Africa Province released a video showing footage from combat with the Nigerian Army in the area.[180] In late December 2018, ISWAP launched another offensive and captured Baga in northeastern Borno State.[158]

On 18 November 2018, ISWAP fighters attacked a military base in the Nigerian town of Metele, killing at least 118 soldiers while at least 153 others were missing after the attack, the militants also seized tanks, armored vehicles, artillery, weapons, and ammunition.[181][182][183][184]

2019

Barnawi's ISWAP launched a major offensive in January 2019, attacking several Nigerian military bases, including those at Magumeri and Gajiram. Insurgents also overran and destroyed the refugee town of Rann near the border to Cameroon, displacing its inhabitants yet again. The destruction of Rann was initially attributed to ISWAP,[158][185] but Shekau's Boko Haram later claimed responsibility.[185]

Three Boko Haram suicide bombers killed 30 people in Konduga, Borno State on 16 June 2019. Boko Haram shot dead at least 65 people in Nganzai, Borno, who were walking home from a funeral on 27 July 2019.

2020

On 6 January, Boko Haram bombed a market in Gamboru, Borno, killing at least 38 people. On 9 February, they killed at least 30 people in Auno, Borno. On 23 March, they carried out massacres against the Chadian and Nigerian armies.

The Chadian Defense Minister, Mahamat Abali Salah, announced on 31 March the launch of “Operation Boma’s Wrath”, in response to Boko the 23 March massacres. The operation's target is to wipe out the Boko Haram remnants around Lake Chad, the operation is named after the island where Boko Haram launched a seven-hour assault, that Chadian President Idriss Déby said, was the worst the country’s military had ever suffered.

On 9 June, Boko Haram killed 81 villagers in a mass shooting in Gubio, Borno State. On 13 June, they killed at least 20 soldiers in Monguno and more than 40 civilians in Nganzai. On 2 August, they killed at least 18 people in an attack on an IDP camp in Far North, Cameroon.

Other issues

Possible causes

The North consisted of Sahelian states that had long Islamic character. These were feudal and conservative, with rigid caste and class systems and large slave populations.[186] Furthermore, the North failed until 1936 to outlaw slavery.[187] Possibly due to geographical factors, many (but not necessarily all) southern tribes, particularly those on the coast, had made contact with Europeans – unlike the North, which was engaged mainly with the Arab world and not Europe. Due to the system of indirect rule, the British were happy to pursue a limited course of engagement with the Emirs. The traditionalist Northern elites were skeptical of Western education;[188][189][190] at the same time their Southern counterparts often sent their sons abroad to study. In time, a considerable developmental and educational gap grew between the South and the North.[191] Even in 2014, Northern states still lagged behind in literacy, school attendance and educational achievement.[192]

Chris Kwaja, a Nigerian university lecturer and researcher, asserted in 2011 that "religious dimensions of the conflict have been misconstrued as the primary driver of violence when, in fact, disenfranchisement and inequality are the root causes". Nigeria, he pointed out, has laws giving regional political leaders the power to qualify people as 'indigenes' (original inhabitants) or not. It determines whether citizens can participate in politics, own land, obtain a job, or attend school. The system is abused widely to ensure political support and to exclude others. Muslims have been denied indigene-ship certificates disproportionately often.[193]

Nigerian opposition leader Buba Galadima said in 2012: "What is really a group engaged in class warfare is being portrayed in government propaganda as terrorists in order to win counter-terrorism assistance from the West."[194]

Human rights

The conflict has seen numerous human rights abuses conducted by the Nigerian security forces, in an effort to control the violence, [195] as well as their encouragement of the formation of numerous vigilante groups (for example, the Civilian Joint Task Force).

Amnesty International accused the Nigerian government of human rights abuses after 950 suspected Boko Harām militants died in detention facilities run by Nigeria's military Joint Task Force in the first half of 2013.[196] As of early 2016, according to Amnesty International, at least 8,000 detainees have died in detention facilities operated by the security services.[197] Furthermore, the Nigerian government has been accused of incompetence and supplying misinformation about events in more remote areas.

Boko Haram has kidnapped several young schoolgirls in Borno, physically, psychologically and sexually abusing them, using and selling them as sex slaves and/or brides of forced marriages with their fighters.[198] – the most famous example being the Chibok kidnapping in 2014. In addition to kidnapping child brides, Human Rights Watch has stated that Boko Harām uses child soldiers, including 12-year-olds.[199] According to an anonymous source working on peace talks with the group, up to 40 percent of the fighters in the group are underage soldiers.[200] The group has forcibly converted non-Muslims to Islam,[201] and is also known to assign non-Kanuris on suicide missions.[202]

Rehabilition of insurgents

A major problem faced by local governments is the rehabilition of captured or surrendered militants, as these are generally suspected by officials and civilians to still hold connections to the rebels and pose a security risk. As result, ex-rebels are often ostracized, which in turn increases the risk of them rejoining the insurgency. Cameroon has planned to construct rehab centers for Boko Haram fighters which are supposed to teach them useful skills to get jobs, and to de-radicalise them. As of February 2019, however, no rehab centers for Boko Haram insurgents had been built yet in Cameroon due to lack of funding.[203]

International context

The insurgence can be seen in the context of other conflicts nearby, for example in the North of Mali. The Boko Harām leadership has international connections to Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Al-Shabaab, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), Mokhtar Belmokhtar's factions, and other militant groups outside Nigeria.[204] In 2014, Nigerian President, Goodluck Jonathan even went so far as calling Boko Harām "al-Qaeda in West Africa".[205] By 2012, attacks by Nigerian Islamist militias on targets beyond Nigeria's borders were still limited,[206] and should not be confused with the activities of other groups (for example, the responsibility of AQIM for most attacks in Niger). Despite this, there were concerns that conflict could spread to Nigeria's neighbours, especially Cameroon, where it existed at a relatively low level until 2014, subsequently escalating considerably. It should also be noted there are combatants from neighboring Chad and Niger.[207] In 2015, Boko Haram swore allegiance to ISIL.[33]

On 17 May 2014, the presidents of Benin, Chad, Cameroon, Nigeria and Niger met for a summit in Paris and agreed to combat Boko Harām on a coordinated basis, sharing in particular surveillance and intelligence gathering. Goodluck Jonathan[208] and Chadian counterpart, Idriss Deby[4] have both declared total war on Boko Harām. Western nations, including Britain, France, Israel, and the United States had also pledged support including technical expertise and training.[209][210] The New York Times reported in March 2015 that hundreds of private military contractors from South Africa and other countries are playing a decisive role in Nigeria's military campaign, operating attack helicopters and armored personnel carriers and assisting in the planning of operations.[10]

See also

- Boko Haram

- Timeline of Boko Haram insurgency

- Religious violence in Nigeria

- Islam in Nigeria

- Islamic extremism in Northern Nigeria

- List of massacres in Nigeria

- Insurgency in the Maghreb (2002–present)

- Northern Mali conflict

- Sinai insurgency

- List of ongoing armed conflicts

Notes

- Following Mohammed Yusuf's death, Boko Haram splintered into numerous factions which no longer operated under a unified leadership. Though Abubakar Shekau eventually became the preeminent commander of the movement, he never really controlled all Boko Haram groups. Instead the factions were loosely allied, but also occasionally clashed with each other.[30][31] This situation changed in 2015, when Shekau pledged allegiance to ISIL.[32][33] The leadership of ISIL eventually decided to replace Shekau as local commander with Abu Mus'ab al-Barnawi, whereupon the movement split completely. Shekau no longer recognized the authority of ISIL's central command, and his loyalists started to openly fight the followers of al-Barnawi.[32] Regardless, Shekau did never officially renounce his pledge of allegiance to ISIL as a whole; his forces are thus occasionally regarded as "second branch of ISWAP". Overall, the relation of Shekau with ISIL remains confused and ambiguous.[34]

- The exact origin of Ansaru is unclear, but it had already existed as Boko Haram faction[39] before officially announcing its foundation as separate group on 1 January 2012.[39][40][41] The group has no known military presence in Nigeria since 2015, but several of its members appear to be still active.[42]

- The number of Boko Haram fighters in 2014 was heavily disputed and varried greatly according to different sources: The U.S. Department of State argued that the group had "hundreds to a few thousand" troops, whereas the Cameroonian Ministry of Defense stated that there were 15,000 to 20,000 Boko Haram militants. A Nigerian journalist even suggested that the group had up to 50,000 followers. Analysts Jason Warner and Charlotte Hulme discounted the higher estimates as "verg[ing] on the ludicrous".[34]

References

- The Christian Science Monitor (13 February 2015). "Boko Haram escalates battle with bold move into Chad". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015.

- Faced with Boko Haram, Cameroon weighs death penalty for terrorism. Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine By Tansa Musa, Reuters. YAOUNDE Wed 3 December 2014 9:56am EST.

- Chad armoured column heads for Cameroon to fight Boko Haram. Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine AFP for Yahoo! News, 16 January 2015 4:54 PM.

- West Africa leaders vow to wage 'total war' on Boko Haram Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine By John Irish and Elizabeth Pineau. 17 May 2014 2:19 PM.

- "Vigilantes Settle Local Scores With Boko Haram". Voice of America. 15 February 2015. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ICG (2018), pp. i, 4–8.

- ICG (2018), pp. 5, 6.

- ICG (2018), pp. i, 3, 7.

- ICG (2018), p. 3.

- Adama Nossiter (12 March 2015). "Mercenaries Join Nigeria's Military Campaign Against Boko Haram". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Colin Freeman (10 May 2015). "South African mercenaries' secret war on Boko Haram". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Union agrees to send 7,500 troops to fight Boko Haram in Nigeria . Mashable.com, 31 January 2015.

- The African Union Readies an Army to Fight Boko Haram Archived 3 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Medium.com.

- "Feeling the heat: West combats extremists' advance in Africa's deserts". CNN. 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Canada joins effort to free Nigerian schoolgirls. Archived 1 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine 14 May 2014 3:23 pm Updated: 15 May 2014 7:01 pm. By Murray Brewster, The Canadian Press

- Kidnapped schoolgirls: British experts to fly to Nigeria 'as soon as possible'. Archived 8 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine theguardian.com, Wednesday 7 May 2014 17.33 BST.

- Iaccino, Ludovica (5 December 2016). "Nigeria turns east: Russia and Pakistan now selling warplanes to help in Boko Haram fight". Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Nigerian Special Forces battalion completes training course in Pakistan". quwa.org. 8 June 2017. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Boko Haram: Obasanjo leads Colombian security experts to Buhari – Premium Times Nigeria". 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "In Pictures: Lt. General Buratai visits Colombia". The NEWS. 25 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- "Egypt Pledges To Support Nigeria in Fight Against Boko Haram • Channels Television". 30 May 2015. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Boko Haram: Egypt assures Nigeria of support – The Nation Nigeria". 20 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Iran ready to help Nigeria over abducted girls: Diplomat. Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine Monday 19 May, 201404:53 PM GMT.

- Israel sends experts to help hunt for Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by Islamists. Archived 10 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Jerusalem Post; 20 May 2014 18:03.

- Andrew McGregor (8 May 2019). "Nigeria Seeks Russian Military Aid in its War on Boko Haram". Aberfoyle International Security. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "British troops to help fight against Boko Haram as SAS target Isil". the Telegraph. 20 December 2014. Archived from the original on 11 February 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- France-Presse, Agence (14 October 2015). "Obama to deploy 300 US troops to Cameroon to fight Boko Haram | World news". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "US troops deployed to Cameroon for Boko Haram fight". Al Jazeera English. 14 October 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- Беларусь попала в ТОП-20 мировых лидеров по экспорту вооружений Archived 27 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine – Военно-политическое обозрение, 1 марта 2017

- TRADOC G-2 (2015), pp. 4, 19.

- ICG 2014, pp. ii, 22, 26, 27.

- Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (5 August 2018). "The Islamic State West Africa Province vs. Abu Bakr Shekau: Full Text, Translation and Analysis". Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Boko Haram swears formal allegiance to ISIS". Associated Press. Fox News. 8 March 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Warner & Hulme (2018), p. 22.

- "Behind Boko Haram's Split: A Leader Too Radical for Islamic State". The Wall Street Journal. 15 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.(subscription required)

- "Boko Haram Split Creates Two Deadly Forces". Voice of America. 2 August 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- "Shekau Resurfaces, Accuses New Boko Haram Leader al-Barnawi of Attempted Coup". 360nobs. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Yinka Ibukun (26 March 2018). "Nigeria Turns to Dialogue to End 9-Year Islamist Insurgency". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ICG 2014, p. 26.

- Sudarsan Raghavan (31 May 2013). "Nigerian Islamist militants return from Mali with weapons, skills". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Steve White (13 March 2013). "Nigerian hostage deaths: British hostage executed in error". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Jacob Zenn (9 December 2017). "Electronic Jihad in Nigeria: How Boko Haram Is Using Social Media". Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ICG 2014, pp. 22–24, 27.

- ICG 2014, pp. 22, 26, 27.

- "Al-Qaeda now has a united front in Africa's troubled Sahel region". Newsweek. 3 March 2017. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- "Islamists Ansaru claim attack on Mali-bound Nigeria troops: paper". Reuters. 20 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013.

- ICG 2014, pp. 22, 26.

- ICG 2014, p. 23.

- AFP (6 March 2019). "ISIS-backed Boko Haram faction may have new chief". News24. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "Nigeria: Boko Haram Resurrects, Declares Total Jihad". allAfrica. Archived from the original on 1 October 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ICG 2014, pp. 26, 27.

- "Khalid al-Barnawi: Nigeria Islamist group head 'arrested'". BBC News. 3 April 2016. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Secret trials of thousands of Boko Haram suspects to start in Nigeria". The Guardian. 9 October 2017. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- "Ansaru: A Profile of Nigeria's Newest Jihadist Movement". Jamestown Foundation. 10 January 2013. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ICG (2018), pp. i, ii.

- ICG (2018), p. ii.

- Warner & Hulme (2018), p. 23.

- "How Big Is Boko Haram?". 2 February 2015. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- "Islamic Militants' Deadly Resurgence Threatens Nigeria Polls". Voice of America. Associated Press. 12 February 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Jacob Zenn (10 December 2018). "Is Boko Haram's notorious leader about to return from the dead again?". African Arguments. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- "Boko Haram 'fighters' surrender as alleged chief killed". BBC. 25 September 2014. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "Nigerian military claims surrender of 200 Boko Haram fighters". Yahoo. 25 September 2015. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "76 starving Boko Haram members surrender to Nigerian military". Fox News. 2 March 2016. Archived from the original on 25 May 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "300 Boko Haram members surrender in Cameroon". Vanguard. 28 September 2014. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "800 Boko Haram militants surrender to Nigeria, General claims". The Independent. 7 April 2016. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "Nigerian troops 'rescue 157 captives as 77 Boko Haram members surrender'". Premium Times. 1 June 2016. Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "Boko Haram in Nigeria". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "ACLED Version 5 (1997–2014)". Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- "Nigeria IDP Figures Analysis". Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- "IOM Highlights Humanitarian Needs of 2.4 Million Displaced in Northeast Nigeria". International Organisation of Migration. 15 April 2016. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Who are Nigeria's Boko Haram Islamists?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- Adama Nossiter (27 July 2009). "Scores Die as Fighters Battle Nigerian Police". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- John Campbell. "Nigeria Security Tracker". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "Boko Haram's four-year reign of terror". Channel 4 News. 8 May 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- "Boko Haram's Bloodiest Year Yet: Over 9,000 Killed, 1.5 Million Displaced, 800 Schools Destroyed in 2014". Christian Post. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Monica Mark (6 January 2015). "Thousands flee as Boko Haram seizes military base on Nigeria border". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "Nigeria Boko Haram: Militants 'technically defeated' – Buhari". BBC News. 24 December 2015. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Pisa, Katie; Hume, Tim (19 November 2015). "Boko Haram overtakes ISIS as world's deadliest terror group, report says". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- "Global Terrorism Index 2015" (PDF). Institute for Economics and Peace. November 2015. p. 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Meredith, Martin. "11. A House Divided". The State of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence. The Free Press. p. 197.

- Holman, Michael (24 February 1986) "Nigeria, Politics; Religious Differences Intensify", Financial Times,

- Ostien & Dekker, 575 (25)

- Jonah, Adamu & Igboeroteonwu, Anamesere (20 May 2014). "Nigerian Sharia architect defends law". BBC. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Olawale, Abdul-Gafar. "Course Lecture: Muslim Groups in Nigeria" (PDF). Unilorin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "Nigeria: First Execution under Sharia Condemned". Human Rights Watch. 8 January 2002. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "Nigeria: International Religious Freedom Report 2008". U.S. Department of State. 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- Amnesty International. Report on Saudi Arabia 2007. Archived from the original. Archived 22 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Amnesty International. Amnesty International Report on Saudi Arabia 2009 Archived 15 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Archived from the original.

- Nigeria: Recent reports regarding the treatment of persons who convert from Islam to Christianity. Recent reports on Sharia law in relation to religious conversion Archived 19 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Ireland: Refugee Documentation Centre, 26 June 2012, Q15539; available at: . Accessed 18 July 2014].

- "Religious Demographic Profile: Nigeria" Archived 21 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine. The Pew Forum, 2010.. Copied archive from original, (archive dated 21 April 2010).

- In the News: The Nigerian Census Archived 15 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Robert Lalasz. (April 2006)

- The Nigeria 2006 Census. Archived 12 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine Thursday, 5 January 2006.

- Cook, David (26 September 2011). "The Rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria". Combating Terrorism Centre. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Nigeria accused of ignoring sect warnings before wave of killings". The Guardian. London. 2 August 2009. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- "Nigerian Islamist attacks spread". BBC. 27 July 2009. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- "Over 100 dead in Nigerian clashes". RTÉ. 27 July 2009. Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- "Nigeria killings caught on video". Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Bartolotta, Christopher (19 September 2011). "Terrorism in Nigeria: the Rise of Boko Haram". The World Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- Boko Haram strikes again in Borno, kills 4 Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Nigerian Tribune, Thursday, 20 January 2011. Archived from the original.

- Omeni, Akali. 2017. Counter-insurgency in Nigeria: The Military and Operations against Boko Haram, 2011–17. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

- Brock, Joe (12 January 2012). "Nigeria sect leader defends killings in video". Reuters Africa. Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- Jacinto, Leela (13 January 2012). "The Boko Haram terror chief who came back from the dead". France 24. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- Adam Nossiter (25 February 2012). "In Nigeria, a Deadly Group's Rage Has Local Roots". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Watt, Nicholas; Norton-Taylor, Richard; Vogt, Andrea (8 March 2012). "British and Italian hostages killed in Nigeria". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- "Civilians among dead in Nigeria offensive". Al Jazeera. 31 May 2013. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- McElroy, Damien (6 July 2013). "Extremist attack in Nigeria kills 42 at boarding school". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Clashes between Nigerian army, Boko Haram kill 35 Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Reuters. Retrieved on 14 August 2013.

- 'Boko Haram' gunmen kill 44 at mosque

- Maclean, Ruth (3 May 2014) Nigerian school says 329 girl pupils missing Archived 11 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine The Times, (the online version may need a subscription), Retrieved 10 May 2014

- "Boko Haram Militants abduct 100+ Teenage Girls in Nigeria". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- Collins, Matt (9 May 2014) #BringBackOurGirls: the power of a social media campaign Archived 15 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, Retrieved 11 May 2014

- "Nigeria rejected British offer to rescue seized Chibok schoolgirls". the Guardian. 4 March 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "2 explosions hit bus station in central Nigeria city". Fox News. 20 May 2014. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Nigeria violence: 'Boko Haram' kill 27 in village attacks". BBC. BBC. 21 May 2014. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- Jonah, Adamu & Igboeroteonwu, Anamesere (20 May 2014). "Bombings kill at least 118 in Nigerian city of Jos". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- "Boko Haram conflict: Nigerian allies launch offensive". BBC. 8 March 2015. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018.

- "Boko Haram conflict: Nigerian allies 'retake Damasak'". BBC. 9 March 2015. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018.

- "Nigeria's Boko Haram 'seize' Bama town in Borno". BBC News. 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- "Nigeria: Boko Haram Kills More Than 50 Elderly People". This Day -- allAfrica.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- Kareem Haruna (22 December 2014). "Nigeria: New Video Shows Boko Haram Shooting Civilians at School Dormitory". Leadership (Abuja) - allAfrica.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- "Nigeria's ignored massacre: 2,000 slaughtered by Boko Haram, 30,000 flee their homes – BelfastTelegraph.co.uk". BelfastTelegraph.co.uk. 12 January 2015. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "Nigeria: Massacre possibly deadliest in Boko Haram's history". Amnesty International. 9 January 2015. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Nossiter, Adam (10 January 2015). "In Nigeria, New Boko Haram Suicide Bomber Tactic: "It's a Little Girl"". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Mark, Monica (25 January 2015). "Nigerian City Under Attack from Suspected Boko Haram Militants". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Faith Karimi & Aminu Abubakar (26 January 2015). "Nigerian soldiers save one city from Boko Haram but a nearby one is seized". CNN.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- "Nigeria army 'repels' new Boko Haram attack on Maiduguri". BBC News. 1 February 2015. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Bomb strapped to girl 'about 10 years old' kills 19 in Maiduguri

- "Nigeria postpones elections, focuses on major offensive against Boko Haram". The Christian Science Monitor. AP. 7 February 2015. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "NYT". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Chadian jets bomb Nigerian town in anti-Boko Haram raid". News24. 5 February 2015. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- "African allies claim gains against Boko Haram". BBC News. 17 February 2015. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- "Nigeria's Boko Haram pledges allegiance to Islamic State". BBC news. BBC. 7 March 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- Adam Chandler (9 March 2015). "The Islamic State of Boko Haram? :The terrorist group has pledged its allegiance to ISIS. But what does that really mean?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- "Boko Haram conflict: Nigerian allies launch offensive". BBC. 8 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "5 suicide bomb blasts rock Maiduguri city in northeast Nigeria, 54 dead, 143 wounded: official". AP. 7 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- "IS welcomes Boko Haram allegiance: tape". AFP. 12 March 2015. Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- Penney, Joe (24 March 2015). "Boko Haram kidnapped hundreds in northern Nigeria town: residents". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Boko Haram HQ Gwoza in Nigeria 'retaken'". BBC. 27 March 2015. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- Michelle Faul & Haruna Umar (28 March 2015). "Boko Haram kills 41 as millions of Nigerians vote in close presidential election". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Ewokor, Chris (21 March 2015) Is the tide turning against Boko Haram? Archived 24 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, Africa, Retrieved 29 April 2015

- (27 March 2015) Boko Haram HQ Gwoza in Nigeria 'retaken' Archived 5 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, Africa, Retrieved 29 April 2015

- (29 April 2015) Nigerian army 'rescues nearly 300' from Sambisa Forest Archived 28 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, Africa, Retrieved 29 April 2015

- (14 April 2015) Nigeria's Chibok girls 'seen with Boko Haram in Gwoza' Archived 1 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, Africa, Retrieved 29 April 2015

- Julia Payne (16 March 2015). "Nigeria military says Bama city recaptured from Boko Haram". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- "Boko Haram HQ Gwoza in Nigeria 'retaken'". BBC News. 27 March 2015. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Corones, Mike (5 May 2015). "Mapping Boko Haram's decline in Nigeria". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "Nigeria frees more children and women from Boko Haram". AlJazeera. 2 May 2015. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- Faul, Michelle (6 May 2015) Nigerian Troops Save 25 More Kids, Women From Boko Haram Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine ABC News, Retrieved 7 May 2015

- Over 1,059 persons killed in 75 major attacks by Boko Haram since Buhari’s inauguration. Archived 8 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine By Methuselah Brozz. Posted: 22 August 2015 13:04 pm WAT.

- "Boko Haram: Nigerian army rescues 338 captives". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- Searcey, Dionne (11 February 2016). "Nigeria Vexed by Boko Haram's Use of Women as Suicide Bombers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Lamb, Christina (20 March 2016). "A fight for the soul of the world". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- "US Sending Troops, Vehicles To Cameroon To Combat Boko Haram". Defensenews.com. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "U.S. special forces wage secretive 'small wars' against terrorists". CNN. 12 May 2016. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- "U.S. soldiers help African armies detect and defeat IEDs". Army times. 31 May 2016.

- Suicide bombers kill 32, wound dozens in northern Cameroon

- "Boko Haram militants 'took my children' in Chad". BBC News Africa. 25 March 2016. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Thomas Joscelyn; Caleb Weiss (17 January 2019). "Thousands flee Islamic State West Africa offensive in northeast Nigeria". Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Nigerian Army Commander: Only Weeks Left for Boko Haram". Asharq al-Awsat. 1 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 September 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Boko Haram 'ousted from Sambisa forest bastion'". BBC News. 24 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Boko Haram 'crushed' by Nigerian army in final forest stronghold". The Independent. 24 December 2016. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- "Buhari: Last Boko Haram base taken in Sambisa Forest". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Boko Haram War Not Yet Over Archived 24 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Roy, Ananya (9 January 2017). "5 Nigerian soldiers, 15 attackers killed in Boko Haram attack on army base in Yobe state". International Business Times UK. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Nigeria air strike error kills up to 100 in refugee camp". BBC News. 17 January 2017. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Nigeria air force jet mistakenly bombs refugees, aid workers". CBC News. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Nigerian military 'mistake' kills at least 50 in attack on safe-haven town". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "Nigeria air strike dead 'rises to 115' in Rann". BBC News Online. 24 January 2017. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "6 killed in Nigeria as teenage girls detonate explosives". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "Nigeria says thwarts Boko Haram plans to attack British and U.S. embassies". Reuters. 12 April 2017. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- "Nigerian army in 'final push' to remove Boko Haram". al Jazeera. 2 April 2017. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "Army arrests 126 Boko Haram suspects in Borno IDPs camp". Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Kelley, Jeremy; Alfa, Ismail (8 September 2017). "Boko Haram kidnaps dozens and kills 18 in brutal raid". The Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Over half of schools remain closed in epicentre of Boko Haram crisis in Nigeria – UNICEF". 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Choi, David. "US Special Forces troops killed 11 ISIS fighters in an undisclosed firefight in Niger". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Omenma, J. Tochukwu; Onyishi, Ike E.; Okolie, Alyious‑Michaels (8 April 2020). "Correction to: A decade of Boko Haram activities: the attacks, responses and challenges ahead". Security Journal. doi:10.1057/s41284-020-00243-5. ISSN 0955-1662.

- "Boko Haram bomb attacks kill four civilians in Nigeria". Shiite News. Shiitenews.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Boko Haram captures Gudumbali after troop attack". Daily Nation. 9 September 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Metele Boko Haram Attack: Soldiers' death toll rises to 118; over 150 missing". premiumtimesng.com. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Militants kill around 100 Nigerian soldiers in attack on army base: sources". Reuters. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Boko Haram attacks leave 53 dead in pre-election show of force". yahoo.com. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Many soldiers killed, dozens injured as insurgents invade base in Borno". dailytrust.com.ng. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Fergus Kelly (17 January 2019). "Shekau Boko Haram faction claims attack in Rann, Nigeria". Defense Post. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Kevin Shillington (2005). Encyclopedia of African History. Michigan University Press. p. 1401. ISBN 1-57958-455-1

- "The end of slavery". The Story of Africa. BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- Dr. Aliyu U. Tilde. "An in-house Survey into the Cultural Origins of Boko Haram Movement in Nigeria" Archived 26 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Discourse 261, MONDAY DISCOURSE WITH DR. ALIYU U. TILDE. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Will Ross. "Nigeria schools walk line between Islamic and Western traditions". Kano, Nigeria; 2 June 2014. Last updated at 00:06 GMT. BBC News online.

- "The Etymology of Hausa 'boko'." Archived 27 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine Paul Newman, 2013. Mega-Chad Research Network / Réseau Méga-Tchad.

- Martin Meredith (2011). "5. Winds of Change". The State of Africa: A History of the Continent Since Independence (illustrated ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 77. ISBN 9780857203892.

- Nigeria: A nation divided. Chart 4: Literacy. Archived 7 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC World News website, 11 January 2012; accessed 5 July 2014.

- Chris Kwaja (July 2011). "Nigeria's Pernicious Drivers of Ethno-Religious Conflict" (PDF). Africa Security Brief. Africa Center for Strategic Studies (14). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2013.

- "Boko Haram's Rise in Nigeria Sparks Civil War Fears". Voanews.com. 21 January 2012. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Nigeria – report – Civilians killed in Nigerian military's fight with Boko Haram, claim rights groups Archived 19 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. By Rosie Collyer. Wednesday 23 November 2011. Latest update: Thursday 24 November 2011.

- "Nigeria: Deaths of hundreds of Boko Haram suspects in custody requires investigation". Amnesty International. 15 October 2013. Archived from the original on 1 June 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- "Another brutal attack by Boko Haram highlights the weakness of Nigeria's military". The Economist. 5 February 2016. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Group asks Nigerian government to rescue 20 ‘kidnapped’ female students in Borno. Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine Premium Times Nigeria; published 27 February 2014.

- "Nigeria's Boko Haram 'uses child soldiers' – Africa". English. Al Jazeera. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- Sotubo, 'Jola. "Boko Haram: Terrorist Group Has 60,000 Fighters – Report". Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Nigeria – reports of forced conversion and marriage of Christians by Boko Haram | Africa – News and Analysis". Africajournalismtheworld.com. 17 November 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- "Genesis, Training And Changing Tactics of Boko Haram Revealed". Talkofnaija.com. 29 January 1970. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012.

- Moki Edwin Kindzeka (18 February 2019). "Cameroon Yet to Build Planned Rehab Centers for ex-Boko Haram Fighters". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- "UN committee imposes sanctions on Nigeria's Boko Haram". Archived 22 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News online, 23 May 2014. Last updated at 15:59 GMT.

- "West's help fuels Boko Haram's jihad – The Star". IOL.co.za. 23 May 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- Walker, Andrew (June 2012). "What is Boko Haram?" (PDF) Archived 9 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. US Institute of Peace. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Captives freed in Nigerian city Archived 28 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News online, 2009-Jul-29.

- Jonathan declares "total war" on Boko Haram Archived 7 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine | Kuramo News, 30 May 2014.

- "Boko Haram to be fought on all sides". Archived 30 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine Nigerian News.Net. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- Boko Haram and the Future of Nigeria Archived 30 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, by Dr. Jacques Neriah Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.

Works cited

- Warner, Jason; Hulme, Charlotte (2018). "The Islamic State in Africa: Estimating Fighter Numbers in Cells Across the Continent" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center. 11 (7): 21–28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johannes Harnischfeger, Democratization and Islamic Law: The Sharia Conflict in Nigeria (Frankfurt am Main 2008). Campus Verlag. ISBN 3593382563

- Philip Ostien & Albert Dekker (2008). ""13. Sharia and national law in Nigeria", in: Sharia Incorporated: A Comparative Overview of the Legal Systems of Twelve Muslim Countries in Past and Present". Leiden University Press. pp. 553–612 (3–62). Archived from the original on 20 October 2014.

- Karl Maier (2002). This House Has Fallen: Nigeria in Crisis (illustrated, reprint ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 9780813340456.

- TRADOC G-2 (2015). Threat Tactics Report: Boko Haram (PDF). Fort Eustis: United States Army Training and Doctrine Command.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Curbing Violence in Nigeria (II): The Boko Haram Insurgency" (PDF). Africa Report. Brussels: International Crisis Group (216). 3 April 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2016.

- "Watchmen of Lake Chad: Vigilante Groups Fighting Boko Haram" (PDF). Africa Report. Brussels: International Crisis Group (244). 23 February 2018.

External links

- Boko Haram Fighting for their Last Territorial Stronghold, 23 April 2015

- Blench, R. M., Daniel, P. & Hassan, Umaru (2003): Access rights and conflict over common pool resources in three states in Nigeria. Report to Conflict Resolution Unit, World Bank (extracted section on Jos Plateau)

- Understanding the Islamist insurgency in Nigeria, 23 May 2014 by Kirthi Jayakumar.

- Muslims should unite to fight Boko Haram Insurgency – Sultan, 30 November 2014