Berbers

Berbers, or Amazighs, (Berber languages: ⵉⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵏ, ⵎⵣⵗⵏ, romanized: Imaziɣen; singular: Amaziɣ, ⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖ ⵎⵣⵗ) are an ethnicity of several nations mostly indigenous to North Africa and some northern parts of West Africa.

Imaziɣen, ⵉⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵏ, ⵎⵣⵗⵏ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| +20–30 million[1][2][3] – +50 million[4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Morocco | from ~18 million[5][6] to ~20 million[2][7] |

| Algeria | from 9[2] to ~13 million[6][8] |

| Libya | ~3,850,000[4] |

| Tunisia | 117,783[9] |

| France | more than 2 million[10] |

| Mauritania | 2,883,000 (2,768,000[11] & 115,000[12]) |

| Niger | 1,620,000[13] |

| Mali | 850,000[14] |

| Belgium | 500,000 (including descendants)[15] |

| Netherlands | 367,455 (including descendants) |

| Burkina Faso | 50,000[16] |

| Egypt | 23,000[17] or 1,826,580[4] |

| Canada | 37,060 (including those of mixed ancestry)[18] |

| Israel | 3,500[19] |

| United States | 1,327[20] |

| Languages | |

| Berber languages (Tamazight), traditionally written with Tifinagh alphabet, also Berber Latin alphabet; Maghrebi Arabic dialects (among Arabized Berbers) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam. Minorities adhere to other Islamic denominations (Shia, Ibadi), Christianity (chiefly Protestantism),[21][22] Judaism, and traditional faith | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Afro-Asiatic peoples[23][24][25][26][27][28][29] | |

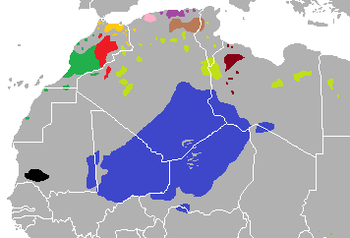

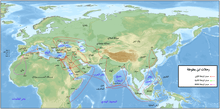

Berbers mostly live in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Mauritania, northern Mali, northern Niger, and a small part of western Egypt.

Berber nations are distributed over an area stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Siwa Oasis in Egypt and from the Mediterranean Sea to the Niger River in West Africa.[30] Historically, Berber nations spoke the Berber languages, which is a branch of the Afroasiatic language family.

There are about 25-30 million Berbers in North Africa who still speak the Berber languages,[3] most living in Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Tunisia, northern Mali, and northern Niger.[4] Smaller Berber-speaking populations are also found in Mauritania, Burkina Faso and Egypt's Siwa town. The majority of North Africa's population west of Egypt is believed to be Berber in ethnic origin, although due to Arabization and Islamization some ethnic Berbers identify as Arabized Berbers.[31] There are large immigrant Berber communities living in France, Spain, Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Italy and other countries of Europe.[32][33]

Name

The term Berber originates from the Greek: βάρβαρος (barbaros pl. βάρβαροι barbaroi) meaning Barbarian. Earlier it was applied by the Romans specifically to their northern hostile neighbours from Germania (modern Germany) and Celts, Iberians, Gauls, Goths and Thracians. Among its oldest written attestations, Berber appears as an ethnonym in the 1st century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.[34]

Despite these early manuscripts, certain modern scholars have argued that the term only emerged around 900 AD in the writings of Arab genealogists,[35] with Maurice Lenoir positing an 8th or 9th-century date of appearance.[36] Ramzi Rouighi argues that the usage of Berber in reference to the people of North Africa appeared only after the Muslim conquests of the 7th-century. Latin and Greek sources describe Moors, Africans and even barbarians, but never Berbers (al-Barbar).[37] The English term was introduced in the 19th century, replacing the earlier Barbary.

The Berbers are the Mauri cited by the Chronicle of 754 during the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, to become since the 11th century the catch-all term Moros (in Spanish; Moors in English) on documents of the Christian Iberian kingdoms to refer to the Andalusi, the north Africans, and the Muslims overall.

For the historian Abraham Isaac Laredo[38] the name Amazigh could be derived from the name of the ancestor Mezeg which is the translation of biblical ancestor Dedan son of Sheba in the Targum. According to Leo Africanus, Amazigh meant "free man", some argued that there is no root of M-Z-Ɣ meaning "free" in modern Berber languages. However, mmuzeɣ "to be noble, generous" exist among the Imazighen of Central Morocco and tmuzeɣ "to free oneself, revolt" among the Kabyles of Ouadhia.[39] This dispute, however, is based on a lack of understanding of the Berber language as "Am-" is a prefix meaning "a man, one who is [...]" Therefore, the root required to verify this endonym would be (a)zigh, "free", which however is also missing from Tamazight's lexicon, but may be related to the well-attested aze "strong", Tizzit "bravery", or jeghegh "to be brave, to be courageous".[40]

Further, it also has a cognate in the Tuareg word Amajegh, meaning "noble".[41][42] This term is common in Morocco, especially among Central Atlas, Rifian and Shilah speakers in 1980,[43] but elsewhere within the Berber homeland sometimes a local, more particular term, such as Kabyle or Chaoui, is more often used instead in Algeria.[44]

The Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Byzantines mentioned various tribes with similar names living in Greater "Libya" (North Africa) in the areas where Berbers were later found. Later tribal names differ from the classical sources, but are probably still related to the modern Amazigh. The Meshwesh tribe among them represents the first thus identified from the field. Scholars believe it would be the same tribe called a few centuries afterwards in Greek as Mazyes by Hektaios and as Maxyes by Herodotus, while it was called after that Mazaces and Mazax in Latin sources, and related to the later Massylii and Masaesyli. Late Antiquity Roman and Coptic sources also mention that Mazices (ⲙⲁⲥⲓⲅⲝ in Coptic)[45] conducted multiple raids against Egypt.[46] all those names are similar and perhaps foreign renditions of the name used by the Berbers in general for themselves, Imazighen or i-Mazigh-en (singular: a-Mazigh).[32]

The name probably had its ancient parallel in the Roman and Greek names for Berbers such as Mazices.[47] According to Ibn Khaldun, the name Mazîgh is derived from one of the early ancestors of the Berbers, based on one opinion.[48]

Prehistory

The Maghreb region in northwestern Africa is believed to have been inhabited by Berbers from at least 10,000 BC.[49] Local cave paintings, which have been dated to twelve millennia before present, have been found in the Tassili n'Ajjer region of southern Algeria. Other rock art has been observed in Tadrart Acacus in the Libyan desert. A Neolithic society, marked by domestication and subsistence agriculture, developed in the Saharan and Mediterranean region (the Maghreb) of northern Africa between 6000 and 2000 BC. This type of life, richly depicted in the Tassili n'Ajjer cave paintings of southeastern Algeria, predominated in the Maghreb until the classical period.

Prehistoric Tifinagh scripts were also found in the Oran region.[50] During the pre-Roman era, several successive independent states (Massylii) existed before the king Masinissa unified the people of Numidia.[51][52][53]

History

In historical times, the Berbers expanded south into the Sahara (displacing earlier populations such as the Azer and Bafour). Much of Berber culture is still celebrated among the cultural elite in Morocco and Algeria.

The areas of North Africa that have retained the Berber language and traditions best have been, in general, Morocco and the Hautes Plaines of Algeria (Kabylie, Aurès etc.), most of which in Roman and Ottoman times had remained largely independent. The Ottomans did penetrate the Kabylie area, and to places the Phoenicians never penetrated, far beyond the coast, where Ottoman influence can be seen in food, clothes and music. These areas have been affected by some of the many invasions of North Africa, most recently that of the French.

Origins

Around 5000 BC, the populations of North Africa were primarily descended from the makers of the Iberomaurusian and Capsian cultures, with a more recent intrusion associated with the Neolithic Revolution.[54] The proto-Berber tribes evolved from these prehistoric communities during the Late Bronze to Early Iron Age.[55]

Uniparental DNA analysis has established ties between Berbers and other Afroasiatic speakers in Africa. Most of these populations belong to the E1b1b paternal haplogroup, with Berber speakers having among the highest frequencies of this lineage.[56] Additionally, genomic analysis has found that Berber and other Maghreb communities are defined by a shared ancestral component that originated in the Near East. This Maghrebi element peaks among Tunisian Berbers.[57] It is related to the Coptic/Ethio-Somali, having diverged from these and other West Eurasian-affiliated components prior to the Holocene.[58]

In 2013, Iberomaurusian skeletons from the prehistoric sites of Taforalt and Afalou in the Maghreb were also analyzed for ancient DNA. All of the specimens belonged to maternal clades associated with either North Africa or the northern and southern Mediterranean littoral, indicating gene flow between these areas since the Epipaleolithic.[59] The ancient Taforalt individuals carried the mtDNA haplogroups U6, H, JT and V, which points to population continuity in the region dating from the Iberomaurusian period.[60]

Human fossils excavated at the Ifri n'Amr or Moussa site in Morocco have been radiocarbon-dated to the Early Neolithic period, ca. 5,000 BC. Ancient DNA analysis of these specimens indicates that they carried paternal haplotypes related to the E1b1b1b1a (E-M81) subclade and the maternal haplogroups U6a and M1, all of which are frequent among present-day communities in the Maghreb. These ancient individuals also bore an autochthonous Maghrebi genomic component that peaks among modern Berbers, indicating that they were ancestral to populations in the area. Additionally, fossils excavated at the Kelif el Boroud site near Rabat were found to carry the broadly-distributed paternal haplogroup T-M184 as well as the maternal haplogroups K1, T2 and X2, the latter of which were common mtDNA lineages in Neolithic Europe and Anatolia. These ancient individuals likewise bore the Berber-associated Maghrebi genomic component. This altogether indicates that the Late Neolithic Kelif el Boroud inhabitants were ancestral to contemporary populations in the area, but also likely experienced gene flow from Europe.[61]

Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), mentioning the oral traditions prevalent in his day, brings down two popular opinions as to the origin of the Berbers. According to one opinion, they are descended from Ham, the son of Noah, and have for ancestor Berber, son of Temla, son of Mazîgh, son of Canaan, son of Ham.[62] Another opinion, being that of Abou-Bekr Mohammed es-Souli (d. 947 CE), holds that they are descended from Berber, the son of Keloudjm (Casluhim), the son of Mesraim, the son of Ham.[62]

Antiquity

The grand tribal identities of Berber antiquity (then often known as ancient Libyans)[63] were said to be three (roughly, from west to east): the Mauri, the Numidians near Carthage, and the Gaetulians. The Mauri inhabited the far west (ancient Mauretania, now Morocco and central Algeria). The Numidians occupied the regions between the Mauri and the city-state of Carthage. Both the Numidians and the Mauri had significant sedentary populations living in villages, and their peoples both tilled the land and tended herds. The Gaetulians were less settled, with predominantly pastoral elements, and lived in the near south on the margins of the Sahara.[64][65][66]

For their part, the Phoenicians (Canaanites) came from the perhaps most advanced multicultural sphere then existing, the western coast of the Fertile Crescent. Accordingly, the material culture of Phoenicia was likely more functional and efficient, and their knowledge more explanatory, than that of the early Berbers. Hence, the interactions between Berbers and Phoenicians were often asymmetrical. The Phoenicians worked to keep their cultural cohesion and ethnic solidarity, and continuously refreshed their close connection with Tyre, the mother city.[67]

The earliest Phoenician landing stations located on the coasts were probably meant merely to resupply and service ships bound for the lucrative metals trade with the Iberian peninsula.[68] Perhaps these newly arrived sea traders were not at first particularly interested in doing much business with the Berbers, for reason of the little profit regarding the goods the Berbers had to offer.[69] The Phoenicians established strategic colonial cities in many Berber areas, including sites outside of present-day Tunisia, e.g., the settlements at Oea, Leptis Magna, Sabratha (in Libya), and Volubilis, Chellah and Mogador (now in Morocco). As in Tunisia, these centres were trading hubs, and later offered support for resource development such as olive oil at Volubilis and Tyrian purple dye at Mogador. For their part, most Berbers maintained their independence as farmers or semi-pastorals although, due to the exemplar of Carthage, their organized politics increased in scope and acquired sophistication.[70]

In fact, for a time their numerical and military superiority (the best horse riders of that time) enabled some Berber kingdoms to impose a tribute payable by Carthage, a condition that continued into the 5th century BC.[71] Also, due to the Berbero-Libyan Meshwesh dynasty's rule of Egypt (945–715 BC),[72] the Berbers near Carthage commanded significant respect (yet probably appearing more rustic than elegant Libyan pharaohs on the Nile). Correspondingly, in early Carthage careful attention was given to securing the most favourable treaties with the Berber chieftains, "which included intermarriage between them and the Punic aristocracy."[73] In this regard, perhaps the legend about Dido, the foundress of Carthage, as related by Trogus is apposite. Her refusal to wed the Mauritani chieftain Hiarbus might be indicative of the complexity of the politics involved.[74]

Eventually, the Phoenician trading stations would evolve into permanent settlements, and later into small towns, which would presumably require a wide variety of goods as well as sources of food, which could be satisfied in trade with the Berbers. Yet here too, the Phoenicians probably would be drawn into organizing and directing such local trade, and also into managing agricultural production. In the 5th century BC, Carthage expanded its territory, acquiring Cape Bon and the fertile Wadi Majardah,[75] later establishing its control over productive farmlands within several hundred kilometres.[76] Appropriation of such wealth in land by the Phoenicians would surely inspire some resistance by the Berbers, although in warfare, too, the technical training, social organization, and weaponry of the Phoenicians would seem to work against the tribal Berbers. This social-cultural interaction in early Carthage has been summarily described:

Lack of contemporary written records makes the drawing of conclusions here uncertain, which can only be based on inference and reasonable conjecture about matters of social nuance. Yet it appears that the Phoenicians generally did not interact with the Berbers as economic equals, but employed their agricultural labour, and their household services, whether by hire or indenture; many became sharecroppers.[77] For a period the Berbers were in constant revolt. In 396 there was a great uprising. "Thousands of rebels streamed down from the mountains and invaded Punic territory, carrying the serfs of the countryside along with them. The Carthaginians were obliged to withdraw within their walls and were besieged." Yet the Berbers lacked cohesion, and although 200,000 strong at one point they succumbed to hunger; their leaders were offered bribes; "they gradually broke up and returned to their homes."[78] Thereafter, "a series of revolts took place among the Libyans [Berbers] from the fourth century onwards."[79]

The Berbers had become involuntary 'hosts' to the settlers from the east, and obliged to accept the Punic dominance of Carthage for many centuries. The Berbers belonged to the lower social class when in Punic society. Nonetheless, therein they persisted largely unassimilated, as a separate, submerged entity, as a culture of mostly passive urban and rural poor within the civil structures created by Punic rule.[80] In addition, and most importantly, the Berber peoples also formed quasi-independent satellite societies along the steppes of the frontier and beyond, where a minority continued as free 'tribal republics'. While benefiting from Punic material culture and political-military institutions, these peripheral Berbers (also called Libyans) maintained their own identity, culture and traditions, continued to develop their own agricultural and village skills, while living with the newcomers from the east in an asymmetric symbiosis.[81][82]

As the centuries passed there naturally grew a Punic society of Phoenician-descent but born in Africa, called Libyphoenicians. This term later came to be applied also to Berbers acculturated to urban Phoenician culture.[83] Yet the whole notion of a Berber apprenticeship to the Punic civilization has been called an exaggeration sustained by a point of view fundamentally foreign to the Berbers.[84] There evolved a population of mixed ancestry, Berber and Punic. There would develop recognized niches in which Berbers had proven their utility. For example, the Punic state began to field Berber Numidian cavalry under their commanders on a regular basis. The Berbers eventually were required to provide soldiers (at first "unlikely" paid "except in booty"), which by the fourth century BC became "the largest single element in the Carthaginian army".[85]

Yet in times of stress at Carthage, when a foreign force might be pushing against the city-state, some Berbers would see it as an opportunity to advance their interests, given their otherwise low status in Punic society. Thus, when the Greeks under Agathocles (361–289 BC) of Sicily landed at Cape Bon and threatened Carthage (in 310 BC), there were Berbers under Ailymas who went over to the invading Greeks.[86] Also, during the long Second Punic War (218–201 BC) with Rome (see below), the Berber King Masinissa (c. 240–148 BC) joined with the invading Roman general Scipio, resulting to the war-ending defeat of Carthage at Zama, despite the presence of their renowned general Hannibal; on the other hand, the Berber King Syphax (d. 202 BC) had supported Carthage. The Romans too read these cues, so that they cultivated their Berber alliances and, subsequently, favored the Berbers who advanced their interests following the Roman victory.[87]

Carthage was faulted by her ancient rivals for the "harsh treatment of her subjects" as well as for "greed and cruelty".[88][89] Her Libyan Berber sharecroppers, for example, were required to pay half of their crops as tribute to the city-state during the emergency of the First Punic War. The normal exaction taken by Carthage was likely "an extremely burdonsome" one-quarter.[90] Carthage once famously attempted to reduce the number of its Libyan and foreign soldiers, leading to the Mercenary revolt (240–237 BC).[91][92][93] Also the city-state seemed to reward those leaders known to deal ruthlessly with its subject peoples. Hence the frequent Berber insurrections. Moderns fault Carthage for failure "to bind her subjects to herself, as Rome did" her Italians. Yet Rome and the Italians held far more in common perhaps than did Carthage and the Berbers. Nonetheless, a modern criticism tells us that the Carthaginians "did themselves a disservice" by failing to promote the common, shared quality of "life in a properly organized city" that inspires loyalty, particularly with regard to the Berbers.[94] Again, the tribute demanded by Carthage was onerous.[95]

The Punic relationship with the majority Berbers continued throughout the life of Carthage. The unequal development of material culture and social organization perhaps fated the relationship to be an uneasy one. A long-term cause of Punic instability, there was no melding of the peoples. It remained a source of stress and a point of weakness for Carthage. Yet there were degrees of convergence on several particulars, discoveries of mutual advantage, occasions of friendship, and family.[96]

The Berbers enter historicity gradually during the Roman era. Byzantine authors mention the Mazikes (Amazigh) as tribal people raiding the monasteries of Cyrenaica. Garamantia was a notable Berber kingdom that flourished in the Fezzan area of modern-day Libya, in the Sahara desert, between 400 BC and 600 AD.

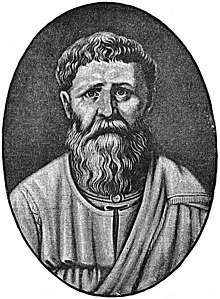

Roman era Cyrenaica became a center of early Christianity. Some pre-Islamic Berbers were Christians[97] (there is a strong correlation between membership of the Donatist doctrine and being Berber, ascribed to its matching their culture as well as their alienation from the dominant Roman culture of the Catholic church),[98] some perhaps Jewish, and some adhered to their traditional polytheist religion. The Roman era authors Apuleius and St. Augustine were born in Numidia. As is true of three popes from the province: Pope Victor I served during the reign of Roman emperor Septimius Severus, who was a North African of Roman/Punic ancestry (perhaps with some Berber blood).[99]

Numidia

Numidia (202 – 46 BC) was an ancient Berber kingdom in modern Algeria and part of Tunisia. It later alternated between being a Roman province and being a Roman client state. The polity was located on the eastern border of modern Algeria, bordered by the Roman province of Mauretania (in modern Algeria and Morocco) to the west, the Roman province of Africa (modern Tunisia) to the east, the Mediterranean to the north, and the Sahara Desert to the south. Its people were the Numidians.

The name Numidia was first applied by Polybius and other historians during the third century BC to indicate the territory west of Carthage, including the entire north of Algeria as far as the river Mulucha (Muluya), about 160 kilometres (100 mi) west of Oran. The Numidians were conceived of as two great groups: the Massylii in eastern Numidia, and the Masaesyli in the west. During the first part of the Second Punic War, the eastern Massylii under their king Gala were allied with Carthage, while the western Masaesyli under king Syphax were allied with Rome.

In 206 BC, the new king of the eastern Massylii, Masinissa, allied himself with Rome, and Syphax of the Masaesyli switched his allegiance to the Carthaginian side. At the end of the war, the victorious Romans gave all of Numidia to Masinissa of the Massylii. At the time of his death in 148 BC, Masinissa's territory extended from Mauretania to the boundary of the Carthaginian territory, and also south-east as far as Cyrenaica, so that Numidia entirely surrounded Carthage (Appian, Punica, 106) except towards the sea.

Masinissa was succeeded by his son Micipsa. When Micipsa died in 118 BC, he was succeeded jointly by his two sons Hiempsal I and Adherbal and Masinissa's illegitimate grandson, Jugurtha, of Berber origin, who was very popular among the Numidians. Hiempsal and Jugurtha quarreled immediately after the death of Micipsa. Jugurtha had Hiempsal killed, which led to open war with Adherbal.

After Jugurtha defeated him in open battle, Adherbal fled to Rome for help. The Roman officials, allegedly due to bribes but perhaps more likely because of a desire to quickly end conflict in a profitable client kingdom, settled the fight by dividing Numidia into two parts. Jugurtha was assigned the western half. However, soon after conflict broke out again, leading to the Jugurthine War between Rome and Numidia.

Mauretania

In antiquity, Mauretania (3rd century BC – 44 BC) was an ancient Mauri Berber kingdom in modern Morocco and part of Algeria. It became a client state of the Roman empire in 33 BC, then a full Roman province after the death of its last king Ptolemy of Mauretania in AD, a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

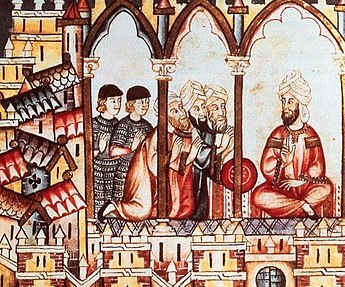

Middle Ages

Before the eleventh century, most of North-West Africa was a Berber-speaking Muslim area. The process of Arabization only became a major factor with the arrival of the Banu Hilal, a tribe sent by the Fatimids of Egypt to punish the Berber Zirid dynasty for having abandoned Shiism. The Banu Hilal reduced the Zirids to a few coastal towns and took over much of the plains; their influx was a major factor in the Arabization of the region and in the spread of nomadism in areas where agriculture had previously been dominant.

After the Muslim conquest, the Berber tribes of coastal North Africa became almost fully Islamized. Besides the Arabian influence, North African population also saw an influx via the Barbary Slave Trade of European peoples, with some estimates placing the number of European slaves brought to North Africa during the Ottoman period as high as 1.25 million.[100] Interactions with neighboring Sudanic empires, traders, and nomads from other parts of Africa also left impressions upon the Berber people.

According to historians of the Middle Ages, the Berbers were divided into two branches, Butr and Baranis (known also as Botr and Barnès), descended from Mazigh ancestors, who were themselves divided into tribes and subtribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several tribes (e.g. Sanhaja, Houaras, Zenata, Masmuda, Kutama, Awraba, Barghawata, etc.). All these tribes had independence and territorial hegemony.[101][102] According to Al-Fiḥrist (Book I, pp. 35–36), the Barber (i.e. Berbers) comprised one of seven principal races in Africa. Medieval Arab historian Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) brings down two opinions as to the Berbers' origin, writing that some say that the Berbers were descended from Canaan, son of Ham. Citing Abu Bakr bin Yahya al-Suli, Ibn Khaldun wrote that they are descended from Casluhim, the son of Mizraïm.[48]

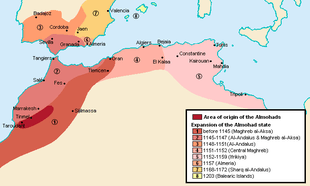

Several Berber dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages in the Maghreb and al-Andalus. The most notable are the Zirids (Ifriqiya, 973–1148), the Hammadids (Western Ifriqiya, 1014–1152), the Almoravid dynasty (Morocco and al-Andalus, 1040–1147), the Almohads (Morocco and al-Andalus, 1147–1248), the Hafsids (Ifriqiya, 1229–1574), the Zianids (Tlemcen, 1235–1556), the Marinids (Morocco, 1248–1465) and the Wattasids (Morocco, 1471–1554).

They belong to a powerful, formidable, brave and numerous people; a true people like so many others the world has seen – like the Arabs, the Persians, the Greeks and the Romans. The men who belong to this family of peoples have inhabited the Maghreb since the beginning.

— Ibn Khaldun, 14th century Tunisian historian[98]

Islamic conquest

Unlike the conquests of previous religions and cultures, the coming of Islam, which was spread by Arabs, was to have extensive and long-lasting effects on the Maghreb. The new faith, in its various forms, would penetrate nearly all segments of Berber society, bringing with it armies, learned men, and fervent mystics, and in large part replacing tribal practices and loyalties with new social norms and political idioms.

Nonetheless, the Islamization and Arabization of the region was a complicated and lengthy process. Whereas nomadic Berbers were quick to convert and assist the Arab conquerors, it was not until the twelfth century, under the Almohad Dynasty, that the Christian, Jewish, and animist communities of the Maghreb became marginalized.

Jews persisted within Northern Africa as dhimmis, protected peoples, under Islamic law. They continued to occupy prominent economic and political roles within the Maghreb.[103] Indeed, some scholars believe that Jewish merchants may have crossed the Sahara, although others dispute this claim. Indigenous Christian communities within the Maghreb all but disappeared under Islamic rule, although Christian communities from Europe may still be found in the Maghreb to this day. The indigenous Christian population in some Nefzaoua villages persisted until the 14th century.[104]

The first Arabian military expeditions into the Maghreb, between 642 and 669, resulted in the spread of Islam. These early forays from a base in Egypt occurred under local initiative rather than under orders from the central caliphate. But when the seat of the caliphate moved from Medina to Damascus, the Umayyads (a Muslim dynasty ruling from 661 to 750) recognized that the strategic necessity of dominating the Mediterranean dictated a concerted military effort on the North African front. In 670, therefore, an Arab army under Uqba ibn Nafi established the town of Qayrawan about 160 kilometres south of modern Tunis and used it as a base for further operations.

.jpg)

Abu al-Muhajir Dinar, Uqba's successor, pushed westward into Algeria and eventually worked out a modus vivendi with Kusaila, the ruler of an extensive confederation of Christian Berbers. Kusaila, who had been based in Tlemcen, became a Muslim and moved his headquarters to Takirwan, near Al Qayrawan. This harmony was short-lived; Arabian and Berber forces controlled the region in turn until 697. Umayyad forces conquered Carthage in 698, expelling the Byzantines, and in 703 decisively defeated Kahina's Berber coalition at the Battle of Tabarka. By 711, Umayyad forces helped by Berber converts to Islam had conquered all of North Africa. Governors appointed by the Umayyad caliphs ruled from Kairouan, capital of the new wilaya (province) of Ifriqiya, which covered Tripolitania (the western part of modern Libya), Tunisia, and eastern Algeria.

The spread of Islam among the Berbers did not guarantee their support for the Arab-dominated caliphate due to the discriminatory attitude of the Arabs. The ruling Arabs alienated the Berbers by taxing them heavily; treating converts as second-class Muslims; and, worst of all, by enslaving them. As a result, widespread opposition took the form of open revolt in 739–40 under the banner of Ibadin Islam. The Ibadin had been fighting Umayyad rule in the East, and many Berbers were attracted by the sect's seemingly egalitarian precepts.

After the revolt, Ibadin established a number of theocratic tribal kingdoms, most of which had short and troubled histories. But others, like Sijilmasa and Tlemcen, which straddled the principal trade routes, proved more viable and prospered. In 750, the Abbasids, who succeeded the Umayyads as Muslim rulers, moved the caliphate to Baghdad and reestablished caliphal authority in Ifriqiya, appointing Ibrahim ibn al Aghlab as governor in Kairouan. Though nominally serving at the caliph's pleasure, Al Aghlab and his successors, the Aghlabids, ruled independently until 909, presiding over a court that became a center for learning and culture.

Just to the west of Aghlabid lands, Abd ar Rahman ibn Rustam ruled most of the central Maghreb from Tahert, south-west of Algiers. The rulers of the Rustamid imamate (761–909), each an Ibadi imam, were elected by leading citizens. The imams gained a reputation for honesty, piety, and justice. The court at Tahert was noted for its support of scholarship in mathematics, astronomy, astrology, theology, and law. The Rustamid imams failed, by choice or by neglect, to organize a reliable standing army. This important factor, accompanied by the dynasty's eventual collapse into decadence, opened the way for Tahert's demise under the assault of the Fatimids. The Muslim Mahdia was founded by the Fatimids under the Caliph Abdallah al-Mahdi in 921 and made the capital city of Ifriqiya, by caliph Abdallah El Fatimi.[105] It was chosen as the capital because of its proximity to the sea, and the promontory on which an important military settlement had been since the time of the Phoenicians.[106]

The Fatimids established the Tunisian city of Mahdia and made it their capital city, before conquering Egypt, and building the city of Cairo in 969.

In al-Andalus under the Umayyad governors

The Muslims who invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 711 were mainly Berbers, and were led by a Berber, Tariq ibn Ziyad, though under the suzerainty of the Arab Caliph of Damascus Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan and his North African Viceroy, Musa ibn Nusayr.[107] Due to subsequent antagonism between Arabs and Berbers, and to the fact that most of the histories of al-Andalus were written from an Arab perspective, the Berber role is understated in the available sources.[107] The biographical dictionary of Ibn Khallikan preserves the record of the Berber predominance in the invasion of 711, in the entry on Tariq ibn Ziyad.[108] A second mixed army of Arabs and Berbers came in 712 under Ibn Nusayr himself. They supposedly helped the Umayyad caliph Abd ar-Rahman I in al-Andalus, because his mother was a Berber.

Roger Collins suggests that if the forces that invaded the Iberian peninsula were predominantly Berber, it is because there were insufficient Arab forces in Africa to maintain control of Africa and attack Iberia at the same time.[109] Thus, although north Africa had only been conquered about a dozen years previously, the Arabs already employed forces of the defeated Berbers to carry out their next invasion.[109] This would explain the predominance of Berbers over Arabs in the initial invasion. In addition, Collins argues that Berber social organization made it possible for the Arabs to recruit entire tribal units into their armies, making the defeated Berbers excellent military auxiliaries.[110] The Berber forces in the invasion of Iberia came from Ifriqiya or as far away as Tripolitania.[111]

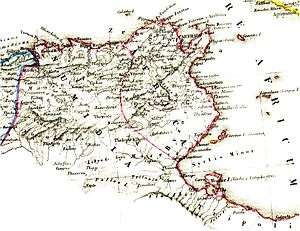

Governor As-Samh distributed land to the conquering forces, apparently by tribe, though it is difficult to determine from the few historical sources available.[112] It was at this time that the positions of Arabs and Berbers was regularized across the Iberian peninsula. Berbers were positioned in many of the most mountainous regions of Spain, such as the mountains of Granada, the Pyrenees, and the mountains of Cantabria and Galicia. Roger Collins suggests this may be because some Berbers were familiar with mountain terrain, whereas the Arabs were not.[113] By the late 710s, there was a Berber governor in Leon or Gijon.[114] When Pelagius revolted in Asturias, it was against a Berber governor. This revolt challenged As-Samh's plans to settle Berbers in the Galician and Cantabrian mountains, and by the middle of the eighth century it seems there was no more Berber presence in Galicia.[113] The expulsion of the Berber garrisons from central Asturias following the battle of Covadonga contributed to the eventual formation of the independent Asturian kingdom.[115]

Many Berbers were settled in what were then the frontier lands near Toledo, Talavera, and Mérida.[116] Mérida became a major Berber stronghold in the eighth century.[117] The Berber garrison in Talavera would later be commanded by Amrus ibn Yusuf and involved in military operations against rebels in Toledo in the late 700s and early 800s.[118] Berbers were also initially settled in the eastern Pyrenees and Catalonia.[119] Berbers were not settled in the major cities of the south, and were generally kept in the frontier zones away from Cordoba.[120]

Roger Collins cites the work of Pierre Guichard to argue that Berber groups in Iberia retained their own distinctive social organization.[121][122][123] According to this traditional view of Arab and Berber culture in the Iberian peninsula, Berber society was highly impermeable to outside influences, whereas Arabs became assimilated and Hispanized.[121] Some support for the view that Berbers assimilated less comes from an excavation of an Islamic cemetery in northern Spain, which reveals that the Berbers accompanying the initial invasion brought their families with them from north Africa.[111][124]

In 731, the eastern Pyrenees were under the control of Berber forces garrisoned in the major towns under the command of Munnuza. Munnuza attempted to lead a Berber uprising against the Arabs in Spain, citing mistreatment of Berbers by Arabic judges in north Africa. Munnuza made an alliance with Duke Eudo of Aquitaine. However, governor Abd ar-Rahman attacked Munnuza before he was ready, and besieging him, defeated him at Cerdanya. Because of the alliance with Munnuza, Abd ar-Rahman wanted to punish Eudo, and his punitive expedition ended in the Arab defeat at Poitiers.[125]

By the time of the governor Uqba, and possibly as early as 714, the city of Pamplona was occupied by a Berber garrison.[126] An eighth century cemetery has been discovered with 190 burials all according to Islamic custom, testifying to the presence of this garrison.[126][127] In 798, however, Pamplona is recorded as being under a Banu Qasi governor, Mutarrif ibn Musa. Ibn Musa lost control of Pamplona to a popular uprising. In 806 Pamplona gave allegiance to the Franks, and in 824 became an independent Kingdom of Pamplona. These events put an end to the Berber garrison in Pamplona.[128]

Al-Hakam wrote that there was a major Berber revolt in north Africa in 740–741, led by Masayra. The Chronicle of 754 calls these rebels Arures, which Collins translates as 'heretics', arguing it is a reference to the Berber rebels' Ibadi or Khariji sympathies.[129] After Charles Martel attacked Arab ally Maurontus at Marseille in 739, governor Uqba planned a punitive attack against the Franks, but news of a Berber revolt in north Africa made him turn back when he reached Zaragoza.[130] Instead, according to the Chronicle of 754, Uqba carried out an attack against Berber fortresses in Africa. Initially these attacks were unsuccessful, but then Uqba destroyed the rebels, secured all the crossing points to Spain, and then returned to his governorship.[131]

Although Masayra was killed by his own followers, the revolt spread and the Berber rebels defeated three Arab armies.[132] After the defeat of the third army, which included elite units of Syrians commanded by Kulthum and Balj, the Berber revolt spread further. At this time, the Berber military colonies in Spain revolted.[133] At the same time, Uqba died and was replaced by Ibn Qatan. By this time, the Berbers controlled most of the north of the Iberian peninsula, except for the Ebro valley, and were menacing Toledo. Ibn Qatan invited Balj and his Syrian troops, who were at that time in Ceuta, to cross to the Iberian peninsula to fight against the Berbers.[134]

The Berbers marched south in three columns, simultaneously attacking Toledo, Cordoba, and the ports on the Gibraltar Straits. However, Ibn Qatan's sons defeated the army of Toledo, the governor's forces defeated the attack on Cordoba, and Balj defeated the attack on the straits. After this, Balj seized power by marching on Cordoba and executing Ibn Qatan.[133] Collins points out that Balj's troops were away from Syria just when the Abbasid revolt against the Umayyads broke out, and this may have contributed to the fall of the Umayyad regime.[135]

In Africa, the Berbers acted under divided leadership. Their attack on Kairouan was defeated, and a new governor of Africa, Hanzala ibn Safwan, proceeded to defeat the rebels in Africa and then to impose peace between Balj's troops and the existing Andalusi Arabs.[136]

Roger Collins argues that the Great Berber revolt facilitated the establishment of the Kingdom of Asturias and altered the demographics of the Berber population in the Iberian peninsula, specifically contributing to the Berber departure from the northwest of the peninsula.[137] When the Arabs first invaded the peninsula, Berber groups were situated in the northwest. However, due to the Berber revolt the Umayyad governors were forced to protect their southern flank and were unable to mount offenses against the Asturians. Some presence of Berbers in the northwest may have been maintained at first, but after the 740s there is no more mention of the northwestern Berbers in the sources.[138]

In al-Andalus during the Umayyad emirate

When the Umayyad dynasty was overthrown in 750, a grandson of Caliph Hisham, Abd ar-Rahman, escaped to north Africa.[139] Abd ar-Rahman hid among the Berbers of north Africa for five years. A persistent tradition states that this is because his mother was Berber.[140] Abd ar-Rahman first took refuge with the Nafsa Berbers, his mother's people. As the governor Ibn Habib was looking for him, he then fled to the more powerful Zanata Berber confederacy, who were enemies of Ibn Habib. Since the Zanata had been part of the initial invasion force of al-Andalus, and were still present in the Iberian peninsula, this gave Abd ar-Rahman a base of support in al-Andalus.[141] However, Abd ar-Rahman seems to have drawn most of his support from portions of Balj's army that were still loyal to the Umayyads.[142][143]

After Abd ar-Rahman crossed to Spain in 756, he declared himself the legitimate Umayyad ruler of al-Andalus. The governor, Yusuf, refused to submit. After losing an initial battle near Cordoba,[144] Yusuf fled to Mérida, where he raised a large Berber army. With this army, Yusuf marched on Seville, but was defeated by forces loyal to Abd ar-Rahman. Yusuf fled to Toledo, and was either killed on the way, or after reaching Toledo.[145] However, Yusuf's cousin Hisham ibn Urwa continued to resist Abd ar-Rahman from Toledo until 764[146] and the sons of Yusuf revolted again in 785. All these family members of Yusuf, members of the Fihri tribe, were very effective at obtaining support from Berbers in their revolts against the Umayyad regime.[147]

As emir of al-Andalus, Abd ar-Rahman I faced persistent opposition from Berber groups, including the Zanata. Berbers provided much of Yusuf's support in fighting against Abd ar-Rahman. In 774 Zanata Berbers were involved in a Yemeni revolt in the area of Seville.[148] Andalusi Berber Salih ibn Tarif declared himself a prophet and ruled the Bargawata in Morocco in the 770s.[149]

In 768, a Miknasa Berber named Shaqya ibn Abd al-Walid declared himself a Fatimid imam, claiming descent from Fatimah and Ali.[148] He is mainly known from the work of Ibn al-Athir.[150] According to Ibn al-Athir, Shaqya's revolt originated in the area of modern Cuenca, an area of Spain that is highly mountainous and challenging to traverse. Shaqya first killed the Umayyad governor of the fortress of Santaver (near Roman Ercavica), and subsequently ravaged the surrounding district of Coria. Abd ar-Rahman sent out armies to fight him in 769, 770, and 771, but Shaqya avoided them by moving into the mountains. In 772, Shaqya defeated an Umayyad force and killed the governor of the fortress of Medellin by a ruse. He was besieged by Umayyads in 774, but the revolt near Seville forced the besieging troops to withdraw. In 775 a Berber garrison in Coria declared allegiance to Shaqya, but Abd ar-Rahman retook the town and chased the Berbers into the mountains. In 776 Shaqya resisted sieges to his two main fortresses at Santaver and Shebat'ran (near Toledo). In 777 Shaqya was betrayed and killed by his own followers, who sent his head to Abd ar-Rahman.[151]

Roger Collins notes that both modern historians and ancient Arab authors have had a tendency to portray Shaqya as a fanatic followed by credulous fanatics, and to argue that he was either self-deluded or fraudulent in his claim of Fatimid descent.[149] However, Collins considers him an example of the messianic leaders that were not uncommon among Berbers at that time and earlier. He compares Shaqya to Idris I, a descendant of Ali accepted by the Zanata Berbers, who founded the Idrisid dynasty in 788, and to Salih ibn Tarif, who ruled the Bargawata Berber in the 770s. He also compares these leaders to pre-Islamic leaders Kahina and Kosayla.[152]

In 788, Hisham succeeded Abd ar-Rahman as emir, but his brother Sulayman revolted. Sulayman fled to the Berber garrison of Valencia, where he held out for two years. Finally he came to terms with Hisham and went into exile in 790, together with other brothers of his who had rebelled with him.[153] In north Africa, Sulayman and his brothers forged alliances with local Berbers, especially the Kharijite ruler of Tahert. After the death of Hisham I and the accession of Al-Hakam, the brothers challenged Al-Hakam for the succession. Abd Allah crossed over to Valencia first in 796, calling on the allegiance of the same Berber garrison that sheltered Sulayman years earlier.[154] Crossing to al-Andalus in 798, Sulayman based himself in Elvira (now Granada), Ecija, and Jaen, apparently drawing support from the Berbers in these mountainous southern regions. Sulayman was defeated in battle in 800 and fled to the Berber stronghold in Mérida, but was captured before reaching it and executed in Cordoba.[155]

In 797, the Berbers of Talavera played a major part in defeating a revolt against Al-Hakam I in Toledo.[156] A certain Ubayd Allah ibn Hamir rebelled in Toledo against Al-Hakam. Al-Hakam order Amrus ibn Yusuf to destroy the rebellion. Amrus was the commander of the Berbers in Talavera. Amrus negotiated in secret with the Banu Mahsa faction in Toledo, promising them the governorship if they betrayed ibn Hamir. The Banu Mahsa brought Ibn Hamir's head to Amrus in Talavera. However, there was a feud between the Banu Mahsa and the Berbers of Talavera. The Berbers of Talavera killed all the Banu Mahsa. Amrus sent the heads of the Banu Mahsa along with that of Ibn Hamir to Al-Hakam in Cordoba. The Toledo rebellion was sufficiently weakened that Amrus was able to enter Toledo and convince its inhabitants to submit.[157]

Roger Collins argues that unassimilated Berber garrisons in al-Andalus engaged in local vendettas and feuds, such as the conflict with the Banu Mahsa.[158] This was due to the limited power of the Umayyad emir's central authority. Collins states that "the Berbers, despite being fellow Muslims, were despised by those who claimed Arab descent."[159] As well as having feuds with Arab factions, the Berbers sometimes had major conflicts with the local communities where they were stationed. In 794, the Berber garrison of Tarragona massacred the inhabitants of the city. Tarragona was uninhabited for seven years until the Frankish conquest of Barcelona led to its reoccupation.[160]

In 829, one of the leaders of the Toledo rebellion of 797, Hashim al-Darrab, who had been kept under arrest in Cordoba, escaped, returned to Toledo, and started another rebellion.[161] From Toledo, Hashim attacked the Berber garrisons of Santaver and Talavera, precisely those that had been involved in suppressing the Toledo rebellion a generation earlier. Hashim gained control of Calatrava la Vieja, then a major fortress town, until 834. Hashim was killed in battle in 831, but his followers maintained the rebellion, and Berbers from Calatrava besieged Toledo in 835 and 836. The rebellion was finally ended in 837, when the emir's brother al-Walid became governor of Toledo.[161]

Throughout the ninth century, the Berber garrisons were one of the main military supports of the Umayyad regime.[162] Although they had caused numerous problems for Abd ar-Rahman I, Collins suggests that by the reign of Al-Hakam, the Berber conflicts with Arabs and native Iberians meant that Berbers could only look to the Umayyad regime for support and patronage, developing solid ties of loyalty to the emirs. However, they were also difficult to control, and by the end of the ninth century the Berber frontier garrisons disappear from the sources. Collins says this might be because they migrated back to north Africa or gradually assimilated.[162]

A Berber leader named H'abiba led a rebellion around Algeciras in 850. Little is known of this rebellion other than its occurrence, and that it may have had a religious inspiration.[163]

Berber groups were involved in the rebellion of Umar ibn Hafsun from 880 to 915.[164] Ibn Hafsun rebelled in 880, was captured, then escaped in 883 to his base in Bobastro. There he formed an alliance with the Banu Rifa' tribe of Berbers, who had a stronghold in Alhama.[165] He then formed alliances with other local Berber clans, taking the towns of Osuna, Estepa, and Ecija in 889. He captured Jaen in 892.[165] He was only defeated in 915 by Abd ar-Rahman III.[166]

In al-Andalus during the Umayyad caliphate

New waves of Berber settlers arrived in al-Andalus in the 10th century, brought in as mercenaries by Abd ar-Rahman III to help him in his campaigns to recover Umayyad authority in areas that had thrown off allegiance to the Umayyads during the reigns of the previous emirs.[167] These new Berbers "lacked any familiarity with the pattern of relationships" that had existed in al-Andalus in the 700s and 800s;[168] thus they were not involved in the same web of traditional conflicts and loyalties as the existing Berber garrisons.[169]

New frontier settlements were built for the Berber mercenaries who arrived in the 900s. Written sources state that some of Abd ar-Rahman's new Berber mercenaries were placed in Calatrava, which was refortified.[169] Another Berber settlement called Vascos, west of Toledo, is not mentioned in the historical sources, but has been excavated archaeologically. It was a fortified town, had walls, and a separate fortress or alcazar. Two cemeteries have been discovered also. It was established in the 900s as a frontier town for Berbers, probably of the Nafza tribe. It was abandoned soon after the Castilian occupation of Toledo in 1085. The Berber inhabitants took all their possessions with them.[170][171]

In the 900s, the Umayyad caliphate faced a challenge from the Fatimids in North Africa. The Fatimid caliphate was founded by Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah after his disciples gained a large following among the Kutama Berbers in what is today eastern Algeria and western Tunisia. After taking the city of Kairouan and overthrowing the Aghlabids in 909, the Mahdi Ubayd Allah declared himself caliph, which represented a direct challenge to the Umayyad's own claim to the caliphate.[170] The Fatimids gained overlordship over the Idrisids, then launched a conquest of the Maghreb. To counter the threat, the Umayyads crossed the straits to take over Ceuta in 931,[172] and actively formed alliances with Berber confederacies such as the Zanata and the Awraba. Rather than fighting each other directly, the competition of Fatimids and Umayyads played out as a competition for Berber allegiances. In turn, this provided a motivation for the further Islamic conversion of Berbers, many of whom, particularly farther south away from the Mediterranean, were still Christian and pagan.[173] In turn, this would contribute to the development of Almoravids and Almohads, which would have a major impact on al-Andalus and contribute to the end of the Umayyad caliphate.[174]

With the help of his new mercenary forces, which were mainly composed of recent Berber arrivals, Abd ar-Rahman launched a series of attacks on parts of the Iberian peninsula that had fallen away from Umayyad allegiance. In the 920s he campaigned against the areas that rebelled under Umar ibn Hafsun and still refused to submit. These he submitted in the 920s. He conquered Mérida in 928–929, Ceuta in 931, and Toledo in 932.[175] In 934 Abd ar-Rahman III began a campaign in the north against Ramiro II of Leon and Muhammad ibn Hashim al-Tujibi, the governor of Zaragoza. According to Ibn Hayyan, after inconclusively confronting al-Tujibi on the Ebro, Abd ar-Rahman briefly forced the Kingdom of Pamplona into submission, ravaged Castile and Alava, and met Ramiro II in an inconclusive battle.[175] From 935 to 937, Abd ar-Rahman confronted the Tujibids, defeating them in 937. In 939 Ramiro II defeated the combined Umayyad and Tujibid armies in the Battle of Simancas.[176]

Umayyad influence in western North Africa spread through diplomacy rather than conquest.[177] The Umayyads sought out alliances with various Berber confederacies. These would declare loyalty to the Umayyad caliphate in opposition to the Fatimids. The Umayyads would send gifts including embroidered silk ceremonial cloaks. During this time, mints in cities on the Moroccan coast (Fes, Sijilmasah, Sfax, and al-Nakur) occasionally issued coins with the names of Umayyad caliphs, showing the extent of Umayyad diplomatic influence.[177] The text of a letter of friendship from a Berber leader to the Umayyad caliph has been preserved in the work of 'Isa al-Razi.[178]

During the reign of Abd ar-Rahman III tensions increased between the three distinct components of the Muslim community in al-Andalus: Berbers, Saqaliba, and those of Arab or mixed Arab and Gothic descent.[179] Following Abd ar-Rahman's proclamation of the new Umayyad caliphate in Cordoba, the Umayyads placed a great emphasis on the Umayyad membership of the Quraysh tribe.[180] This led to a fashion in Cordoba for claiming pure Arab ancestry as opposed to descent from freed slaves.[181] Claims of descent from Visigothic noble families also became common.[182] However, an "immediately detrimental consequence of this acute consciousness of ancestry was the revival of ethnic disparagement, directed in particular against the Berbers and the Saqaliba."[183]

When the Fatimids moved their capital to Egypt in 969, they left north Africa in charge of viceroys from the Zirid clan of Sanhaja Berbers, who were Fatimid loyalists and enemies of the Zanata.[174] The Zirids in turn divided their territories, assigning some to the Hammadid branch of the family to govern. The Hammadids became independent in 1014, with their capital at Qal'at Beni-Hammad. With the withdrawal of the Fatimids to Egypt, however, the rivalry with the Umayyads decreased.[174]

Al-Hakam II sent Muhammad Ibn Abi Amir to north Africa in 973–974 to act as qadi al qudat to the Berber groups that had accepted Umayyad authority. Ibn Abi Amir was treasurer of the household of the caliph's wife and children, director of the mint at Madinat al-Zahra, commander of the Cordoba police, and qadi of the frontier. During his time as qadi in north Africa, Ibn Abi Amir developed close ties with the North African Berbers.[184]

On the death of Al-Hakam II, the heir Hisham II was underage, and the position of hajib was occupied by a Berber named al-Mushafi. However, general Ghalib ibn Abd ar-Rahman and Muhammad Ibn Abi Amir formed an alliance, and in 978 they overthrew al-Mushafi and his sons and other family members, who had received offices. Al-Mushafi was imprisoned for five years before being killed, and his family was stripped of property and titles.[185]

In 980, Ibn Abi Amir fell out with his ally Ghalib, and a civil war began.[186] Ibn Abi Amir called on the Berbers he had lived with in 973–974 to come help him.[187] His Berber ally Jafar ibn Hamdun crossed the straits with his army, whereas Ghalib allied with the Kingdom of Navarre. These armies fought several battles, in the last one of which Ghalib was killed, bringing the civil war to an end. Ibn Abi Amir then took on the name al-Mansur, 'the victorious', by which he is more commonly known.[187]

Having won the war, al-Mansur no longer needed his Berber ally Ibn Hamdun, who instead became a threat due to his substantial army. Ibn Hamdun was murdered in 983, having been made drunk at a feast held in his honor, then murdered as he departed.[187] According to Ibn Idhari, his head and one hand were then presented in secret to al-Mansur.[187]

Employing large numbers of Berber and Saqaliba mercenaries, al-Mansur intitiated a series of highly successful attacks on the Christian portions of the peninsula.[188] Among the most memorable campaigns were the sack of Barcelona in 985, the destruction of Leon in 988, the capture of Count Garcia Fernandez of Castile in 995, and the sack of Santiago in 997.[189] Al-Mansur died in 1002. He was succeeded as hajib by his son, Abd al-Malik. In 1008, Abd al-Malik died and was succeeded as hajib by his half-brother, Abd ar-Rahman, known as Sanchuelo because his mother was Navarrese.[190] Meanwhile, Hisham II remained caliph, though this had become a ceremonial position.

Considerable resentment arose in Cordoba against the increasing numbers of Berbers brought from north Africa by al-Mansur and his children Abd al-Malik and Sanchuelo.[191] It was said that Sanchuelo ordered anyone attending his court to wear Berber turbans, which Roger Collins suggests may not have been true, but shows that hostile anti-Berber propaganda was being used to discredit the sons of al-Mansur. In 1009, Sanchuelo had himself proclaimed Hisham II's successor, and then went on military campaign. However, while he was away a revolt took place. Sanchuelo's palace was sacked and his support fell away. As he marched back to Cordoba his own Berber mercenaries abandoned him.[192] Knowing the strength of ill feeling against them in Cordoba, they thought Sanchuelo would be unable to protect them and so they went elsewhere in order to survive and secure their own interests.[191] Sanchuelo was left with only a few followers, and was captured and killed in 1009. Hisham II abdicated and was replaced by Muhammad II al-Mahdi.

Having abandoned Sanchuelo, the Berbers who had formed his army turned to another ambitious Umayyad, Sulayman, whom they supported. They obtained logistical support from Count Sancho Garcia of Castile. Marching on Cordoba, they defeated Saqaliba general Wadih and forced Muhammad II al-Mahdi to flee to Toledo. They then installed Sulayman as caliph, and based themselves in the Madinat al-Zahra to avoid friction with the local population.[193] Wadih and al-Mahdi formed an alliance with the Counts of Barcelona and Urgell and marched back on Cordoba. They defeated Sulayman and the Berber forces in a battle near Cordoba in 1010. To avoid being destroyed, the Berbers left Cordoba and fled towards Algeciras.[194]

Al-Mahdi swore to exterminate the Berbers, and pursued them. However, he was defeated in battle near Marbella. With Wadih, he fled back to Cordoba while his Catalan allies went home. The Berbers turned around and besieged Cordoba. Deciding that he was about to lose, Wadih overthrew al-Mahdi and sent his head to the Berbers, replacing him with Hisham II.[194] However, the Berbers did not end the siege. They methodically destroyed Cordoba's suburbs, pinning the inhabitants inside the old Roman walls and destroying the Madinat al-Zahra. Wadih's allies killed him, and the Cordoba garrison surrendered with the expectation of amnesty. However, "a massacre ensued in which the Berbers took revenge for many personal and collective injuries and permanently settled several feuds in the process."[195] The Berbers made Sulayman caliph once again. Ibn Idhari said that the installation of Sulayman in 1013 was the moment when "the rule of the Berbers began in Cordoba and that of the Umayyads ended, after it had existed for two hundred and sixty eight years and forty-three days."[195][196]

In al-Andalus in the Taifa period

During the Taifa era, the petty kings came from a variety of ethnic groups; some—for instance the Zirid kings of Granada—were of Berber origin. The Taifa period ended when a Berber dynasty—the Moroccan Almoravids—took over al-Andalus; they were succeeded by the Almohad dynasty of Morocco, during which time al-Andalus flourished.

After the fall of Cordoba in 1013, the Saqaliba fled from the city to secure their own fiefdoms. One group of Saqaliba seized Orihuela from its Berber garrison and took control of its entire region.[197]

Among the Berbers who were brought to al-Andalus by al-Mansur were the Zirid family of Sanhaja Berbers. After the fall of Cordoba, the Zirids took over Granada in 1013, forming the Zirid kingdom of Granada. The Saqaliba Khayran, with his own Umayyad figurehead Abd ar-Rahman IV al-Murtada, attempted to seize Granada from the Zirids in 1018 but failed. Khayran then executed Abd ar-Rahman IV. Khayran's son, Zuhayr, also made war on the Zirid kingdom of Granada, but was killed in 1038.[198]

In Cordoba, conflicts continued between the Berber rulers and those of the citizenry who saw themselves as Arab.[198] After being installed as caliph with Berber support, Sulayman was pressured into distributing southern provinces to his Berber allies. The Sanhaja departed from Cordoba at this time. The Zanata Berber Hammudids received the important districts of Ceuta and Algeciras. The Hammudids claimed a family relation to the Idrisids, and thus traced their ancestry to the caliph Ali. In 1016 they rebelled in Ceuta, claiming to be supporting the restoration of Hisham II. They took control of Málaga, then marched on Cordoba, taking it and executing Sulayman and his family. Ali ibn Hammud al-Nasir declared himself caliph, a position he held for two years.[199]

For some years, Hammudids and Umayyads fought one another and the caliphate passed between them several times. Hammudids also fought among themselves. The last Hammudid caliph reigned until 1027. The Hammudids were then expelled from Cordoba, where there was still a great deal of anti-Berber sentiment. The Hammudids remained in Malaga until expelled by the Zirids in 1056.[199] The Zirids of Granada controlled Malaga until 1073, after which separate Zirid kings retained control over the taifas of Granada and Malaga until the Almoravid conquest.[200]

During the taifa period, the Aftasid dynasty based in Badajoz controlled a large territory centered on the Guadiana River valley.[200] The area of Aftasid control was very large, stretching from the Sierra Morena and the taifas of Mertola and Silves to the south, to the Campo de Calatrava in the west and the Montes de Toledo in the northwest and nearly as far as Oporto in the northeast.[200]

According to Bernard Reilly,[201] during the taifa period genealogy continued to be an obsession of the upper classes in al-Andalus. Most wanted to trace their lineage back to the Syrian and Yemeni Arabs who accompanied the invasion. In contrast, tracing descent from the Berbers who came with the same invasion "was to be stigmatized as of inferior birth."[201] Reilly notes, however, that in practice the two groups had by the 11th century become almost indistinguishable: "both groups gradually ceased to be distinguishable parts of the Muslim population, except when one of them actually ruled a taifa, in which case his origins were well publicized by his rivals. Nevertheless, distinctions between Arab, Berber, and slave were not the stuff of serious politics either within or between the taifas. It was the individual family that was the unit of political activity."[201] The Berber that arrived towards the end of the caliphate as mercenary forces, says Reilly, amounted to only about 20 thousand people in a total al-Andalusi population of six million. Their high visibility was due to their foundation of taifa dynasties rather than large numbers.[201]

In the power hierarchy, Berbers were situated between the Arabic aristocracy and the Muladi populace. Ethnic rivalry was one of the most important factors driving Andalusi politics. Berbers made up as much as 20% of the population of the occupied territory.[202] After the fall of the Caliphate, the Taifa kingdoms of Toledo, Badajoz, Málaga and Granada had Berber rulers. During the Reconquista, Berbers in the areas which became Christian kingdoms were acculturated and lost their ethnic identity, their descendants being among modern Spanish and Portuguese peoples.

In al-Andalus under the Almoravids

During the taifa period, the Almoravid empire developed in northwest Africa. The core of the Almoravid empire was formed by the Lamtuna branch of the Sanhaja Berber.[203] In the mid 11th century, they allied with the Guddala and Massufa Berber. At that time, the Almoravid leader Yahya ibn Ibrahim went on a hajj. On his way back he met Malikite preachers in Kairouan, and invited them to his land. Malikite disciple Abd Allah ibn Yasin accepted the invitation. Traveling to Morocco, he established a military monastery or ribat where he trained a highly motivated and disciplined fighting force. In 1054 and 1055, employing these specially trained forces, Almoravid leader Yahya ibn Umar defeated the Kingdom of Ghana and the Zanata Berber. After Yahya ibn Umar died, his brother Abu Bakr ibn Umar pursued the expansion of the Almoravids. Forced to resolve a Sanhaja civil war, he left control of the Moroccan conquests to his brother, Yusuf ibn Tashufin. Yusuf continued to conquer territory, and following Abu Bakr's death in 1087, Yusuf became the Almoravid leader.[204]

After their loss of Cordoba, the Hammudids had occupied Algeciras and Ceuta. In the mid-11th century, the Hammudids lost control of their Iberian possessions, but retained a small taifa kingdom based in Ceuta. In 1083, Yusuf ibn Tashufin conquered Ceuta. In the same year, al-Mutamid, king of the Sevilla taifa, traveled to Morocco to appeal to Yusuf for help against King Alfonso VI of Castile. Earlier, in 1079, the king of Badajoz, al-Mutawakkil, had appealed to Yusuf for help against Alfonso. After the fall of Toledo to Alfonso VI in 1085, al-Mutamid appealed again to Yusuf. This time, financed by the taifa kings of Iberia, Yusuf crossed to al-Andalus, taking direct personal control of Algeciras in 1086.[205]

Modern history

The Kabylians were independent of outside control during the period of Ottoman Empire rule in North Africa. They lived primarily in three states or confederations: the Kingdom of Ait Abbas, Kingdom of Kuku, and the principality of Aït Jubar.[206] The Kingdom of Ait Abbas was a Berber state of North Africa, controlling Lesser Kabylie and its surroundings from the sixteenth century to the nineteenth century. It is referred to in the Spanish historiography as "reino de Labes";[207] sometimes more commonly referred to by its ruling family, the Mokrani, in Berber At Muqran (Arabic: أولاد مقران Ouled Moqrane). Its capital was the Kalâa of Ait Abbas, an impregnable citadel in the Biban mountain range.

The most serious native revolt against French colonial power in Algeria since the time of Abd al-Qadir broke out in 1871 in the Kabylie and spread through much of Algeria. By April 1871, 250 tribes had risen, or nearly a third of Algeria's population.[208] In 1902, the French penetrated Hoggar Mountains and defeated Ahaggar Tuareg in the battle of Tit.

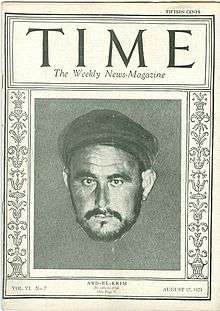

In 1911, Morocco was divided between the French and Spanish. The Rif Berbers rebelled, led by Abd el-Krim, a former officer for the Spanish administration. In July 1921, the Spanish army in north-eastern Morocco under Manuel Silvestre collapsed when defeated by the forces of Abd el-Krim, in what became known in Spain as the disaster of Annual. The Spaniards may have lost up to 22,000 soldiers at Annual and in subsequent fighting.[209]

During the Algerian War (1954–1962), the FLN and ALN's reorganisation of the country created, for the first time, a unified Kabyle administrative territory, wilaya III, being as it was at the centre of the anti-colonial struggle.[210] From the moment of Algerian independence, tensions had developed between Kabyle leaders and the central government.[211]

There is an identity-related debate about the persecution of Berbers by the Arab-dominated regimes of North Africa. Through both exclusivities of Pan-Arabism and Islamism,[212] their issue of identity is due to the pan-Arabist ideology of the former Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Some activists have claimed that "It is time—long past overdue—to confront the racist arabization of the Amazigh lands."[213]

Soon after independence in the middle of the twentieth century, the countries of North Africa established Arabic as their official language, replacing French, Spanish and Italian; although the shift from European colonial languages to Arabic for official purposes continues even to this day. As a result, most Berbers had to study and know Arabic, and had no opportunities until the twenty-first century to use their mother tongue at school or university. This may have accelerated the existing process of Arabization of Berbers, especially in already bilingual areas, such as among the Chaouis of Algeria. Tamazight is now taught in Aures since the march led by Salim Yezza in 2004, which has started to the teaching of Tamazight in the schools in Aures.

While Berberism had its roots before the independence of these countries, it was limited to the Berber elite. It only began to gain success among the greater populace when North African states replaced their European colonial languages with Arabic and identified exclusively as Arabian nations, downplaying or ignoring the existence and the social specificity of Berbers. However, its distribution remains highly uneven. In response to its demands, Morocco and Algeria have both modified their policies, with Algeria redefining itself constitutionally as an "Arab, Berber, Muslim nation".

In Morocco, after the constitutional reforms of 2011, Berber has become an official language, and is now taught as a compulsory language in all schools regardless of the area or the ethnicity. In 2016, Algeria followed suit and changed the status of Berber from national language" to an official language.

Berbers have reached high positions in the social hierarchy across the Maghreb; good examples are the former president of Algeria, Liamine Zeroual, and the former prime minister of Morocco, Driss Jettou.

Nevertheless, Berberists who openly show their political orientations rarely reach high hierarchical positions. But, there are some exceptions; for example, Khalida Toumi, a feminist and Berberist militant, has been nominated as head of the Ministry of Communication in Algeria.

The Black Spring was a series of violent disturbances and political demonstrations by Kabyle activists in the Kabylie region of Algeria in 2001. In the 2011 Libyan civil war, Berbers in the Nafusa Mountains were quick to revolt against the Gaddafi regime. The mountains became a stronghold of the rebel movement, and were a focal point of the conflict, with much fighting occurring between rebels and loyalists for control of the region.[3] The Tuareg Rebellion of 2012 was waged against the Malian government by rebels with the goal of attaining independence for the northern region of Mali, known as Azawad.[214] Since late 2016, massive riots have spread across Moroccan Berber communities in the Rif region. Another escalation took place in May 2017.[215]

Contemporary demographics

The Maghreb today is home to large Berber (Amazigh) populations, who form the principal indigenous ancestry in the region (see Origins).[216][217][218][219][220][221][222][223][224][225] The Semitic ethnic presence in the region is mainly due to the Phoenicians, Jews and Arab Bedouin Hilallians migratory movements (third century BC and eleventh century, respectively) which mixed in. However, the majority of Arabized Berbers, particularly in Morocco and Algeria, claim an Arabian heritage; this is a consequence of the Arab nationalism of the early twentieth century.

The remaining populations that speak a Berber language in the Maghreb comprise 50%[3] to 60%[7][6] of the Moroccan population and from[31] 15% to 35%[6] of the Algerian population, with smaller communities in Libya and Tunisia and very small groups in Egypt and Mauritania.

Outside the Maghreb, the Tuareg in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso number some 850,000,[226] 1,620,000[227] and 50,000 respectively although Tuaregs are Berber people with a traditionally nomadic pastoralist lifestyle. They are the principal inhabitants of the vast Sahara Desert.[228][229]

Prominent Berber groups include the Kabyles from Kabylia, a historical autonomous region of northern Algeria, who number about six million and have kept, to a large degree, their original language and society; and the Shilha or Chleuh (French, from Arabic Shalh and Shilha ašəlḥi) in High and Anti-Atlas and Souss Valley of Morocco, numbering about eight million. Other groups include the Riffians of northern Morocco, the Chaoui people of eastern Algeria, the Chenouas in western Algeria, the Berbers of Tripolitania and the Tuaregs of the Sahara scattered through several countries.

Though stereotyped in Europe and North America as nomads, most Berbers were in fact traditionally farmers, living in mountains relatively close to the Mediterranean coast, or oasis dwellers, such as the Siwa of Egypt; but the Tuareg and Zenaga of the southern Sahara were almost wholly nomadic. Some groups, such as the Chaouis, practiced transhumance.

Political tensions have arisen between some Berber groups (especially the Kabyle, and Riffians) and North African governments over the past few decades, partly over linguistic and social issues; for instance, in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, giving children Berber names was banned. The regime of Muammar Gaddafi (ironically an Arabized Berber by ancestry) in Libya also banned the teaching of Berber languages, and the leader warned Berber leaders in a 2008 diplomatic cable leaked by WikiLeaks "You can call yourselves whatever you want inside your homes – Berbers, Children of Satan, whatever – but you are only Libyans when you leave your homes."[230] As a result of the persecution suffered under Gaddafi's rule, many Berbers joined the Libyan opposition in the 2011 Libyan civil war.[231]

Diaspora

Berbers set up communities In Mauritania[232] near the Malian imperial capital of Timbuktu.[233] According to an estimate from 2004, there were about 2.2 million Berber immigrants in Europe, especially the Riffians in Belgium, the Netherlands and France and Algerians of Kabyles and Chaouis heritage in France.[234]

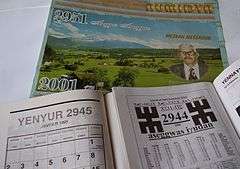

Languages

The Berber languages form a branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. They thus descend from the proto-Afroasiatic language. It is still disputed which branches of Afroasiatic diverged most recently from Berber, but most linguists accept either Egyptian[235] or Chadic (see Afro-Asiatic languages).

Berber languages are spoken by around thirty to forty million people in Africa (see population estimation). These Berber speakers are mainly concentrated in Morocco and Algeria, followed by Mali, Niger and Libya. Smaller Berber-speaking communities are also found as far east as Egypt, with a southwestern limit today at Burkina Faso.

Tamazight is a generic name for all of the Berber languages. They consist of many closely related varieties/dialects. Among these Berber idioms are Riff, Kabyle, Shilha, Siwi, Zenaga, Sanhaja, Tazayit (Central Atlas Tamazight), Tumẓabt (Mozabite), Nafusi, and Tamasheq, as well as the ancient Guanche language.

Groups

Although most Maghrebis are of Berber ancestry, only some scattered ethnicities succeeded in preserving Berber languages into modern times.

| Group | Country | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Blida/Médéa Atlas Berbers | Algeria | in Central Algeria. |

| Chaoui people | Algeria | Found mainly in Eastern Algeria. |

| Chenini and Douiret Berbers | Tunisia | |

| Chenoui Berbers | Algeria | Ouarsenis and Mount Chenoua (Western Algeria). |

| Chleuhs | Morocco | the High Atlas, Anti-Atlas and the Sous valley. |

| Djerba Berbers | Tunisia | speakers of the Djerbi language. |

| Kabyles | Algeria | in Kabylie. |

| Matmata Berbers | Tunisia | in Southern Tunisia. |

| Mozabites | Algeria | in the M'zab Valley (southern Algeria). |

| Nafusis | Libya | in western Libya. |

| Riffians | Morocco | primarily in northern Morocco, with some also in Algeria. |

| Sanhaja | Mauritania, Morocco and Senegal | in southwestern Mauritania, Middle Atlas mountains and eastern Morocco, and northern Senegal. |

| Siwi | Egypt | in the Siwa valley of Egypt. |

| Tlemcen Berbers | Algeria | Aït Snouss villages of western Algeria. |

| Tuareg | Algeria, Libya, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso | Sahara (southern Algeria and north of the Sahel). |

| Zayanes | Morocco | Middle Atlas mountains of Morocco. |

| Zenatas | Morocco and Algeria | in northern and northeastern Morocco and western-central Algeria. |

| Zuwaras | Libya | in northwestern Libya. |

Religion

The Berber identity is wider than language, religion, and ethnicity and encompasses the entire history and geography of North Africa. Berbers are not an entirely homogeneous ethnicity, and they include a range of societies, ancestries and lifestyles. The unifying forces for the Berber people may be their shared language or a collective identification with Berber heritage and history.

As a legacy of the spread of Islam, the Berbers are now mostly Muslim. The Mozabite Berbers of the Saharan Mozabite Valley and Libyan berbers in Nafusis and Zuwara are primarily adherents of the Ibadi Muslim denomination.

In antiquity, the Berber people adhered to the traditional Berber religion, prior to the arrival of Abrahamic faiths into North Africa. This traditional religion heavily emphasized ancestor veneration, polytheism and animism. Many ancient Berber beliefs were developed locally, whereas others were influenced over time through contact with other traditional African religions (such as the Ancient Egyptian religion), or borrowed during antiquity from the Punic religion, Judaism, Iberian mythology, and the Hellenistic religion. The most recent influence came from Islam and pre-Islamic Arab religion during the medieval period. Some of the ancient Berber beliefs still exist today subtly within the Berber popular culture and tradition.

Until the 1960s, there was also a significant Jewish Berber minority in Morocco,[236] but emigration (mostly to Israel and France) dramatically reduced their number to only a few hundred individuals.

Following Christian missions, the Kabyle community in Algeria has a recently constituted Christian minority, both Protestant and Roman Catholic, and a 2015 study estimates 380,000 Muslim Algerians converted to Christianity in Algeria.[21] whereas among the 8,000[237]-40,000[238] Moroccans who have converted to Christianity in the last decades several Berbers are found; some of them explain their conversion as an attempt to go back to their "Christian sources".[239] International Religious Freedom Report for 2007 estimates thousands of Tunisian Berber Muslims have converted to Christianity.[240][241]

Notable Berbers