Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba (Arabic: خلافة قرطبة; trans. Khilāfat Qurṭuba) was a state in Islamic Iberia along with a part of North Africa ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. The state, with the capital in Córdoba, existed from 929 to 1031. The region was formerly dominated by the Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba (756–929). The period was characterized by an expansion of trade and culture, and saw the construction of masterpieces of al-Andalus architecture. In January 929, Abd ar-Rahman III proclaimed himself Caliph (Arabic: خليفة) of Córdoba,[3] replacing thus his original title of Emir of Córdoba (Arabic: أمير قرطبة 'Amīr Qurṭuba). He was a member of the Umayyad dynasty, which had held the title of Emir of Córdoba since 756.

Caliphate of Córdoba خلافة قرطبة Khilāfat Qurṭuba (in Arabic) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 929–1031 | |||||||||||||

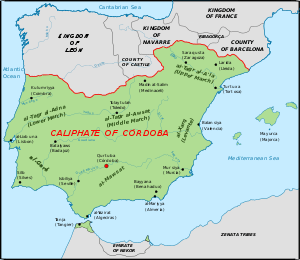

Caliphate of Córdoba (green), c. 1000. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Córdoba | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||||

| Government | Theocratic monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Caliph | |||||||||||||

• 929 – 961 | Abd ar-Rahman III | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Abd ar-Rahman III proclaimed Caliph of Córdoba[1] | 929 | ||||||||||||

• Disintegrated into several independent taifa kingdoms | 1031 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1000 est.[2] | 600,000 km2 (230,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1000 est. | 7,000,000 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Gibraltar (UK) Morocco Portugal Spain | ||||||||||||

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

Main caliphates |

|

Parallel caliphates |

|

|

| Historical Arab states and dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient Arab States

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arab Empires

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eastern Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Western Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arabian Peninsula

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

East Africa

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Current monarchies

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Al-Andalus |

|---|

|

Muslim conquest (711–732) |

|

Umayyads of Córdoba (756–1031) |

|

|

First Taifa period (1009–1110) |

|

Almoravid rule (1085–1145) |

|

Second Taifa period (1140–1203) |

|

Almohad rule (1147–1238) |

|

Third Taifa period (1232–1287) |

|

Emirate of Granada (1238–1492) |

| Related articles |

The caliphate disintegrated during the Fitna of al-Andalus, a civil war between the descendants of the last caliph, Hisham II, and the successors of his hayib (court official), Al-Mansur. In 1031, after years of infighting, the caliphate fractured into a number of independent Muslim taifa (kingdoms).[4]

History

Umayyad Dynasty

Rise

Abd ar-Rahman I became Emir of Córdoba in 756 after six years in exile after the Umayyads lost the position of Caliph in Damascus to the Abbasids in 750.[5] Intent on regaining power, he defeated the area's existing Islamic rulers and united various local fiefdoms into an emirate.[6] Raids then increased the emirate's size; the first to go as far as Corsica occurred in 806.[7]

The emirate's rulers used the title "emir" or "sultan" until the 10th century. In the early 10th century, Abd ar-Rahman III faced a threatened invasion from North Africa by the Fatimid Caliphate, a rival Shiite Islamic empire based in Ifriqiya. Since the Fatimids also claimed the caliphate, in response Abd ar-Rahman III claimed the title of caliph himself.[8] Prior to Abd ar-Rahman's proclamation as the caliph, the Umayyads generally recognized the Abbasid Caliph of Baghdad as being the rightful rulers of the Muslim community.[9] Even after repulsing the Fatimids, he kept the more prestigious title.[10] Although his position as caliph was not accepted outside of al-Andalus and its North African affiliates, internally the Spanish Umayyads considered themselves as closer to Muhammad, and thus more legitimate, than the Abbasids.

Prosperity

The caliphate enjoyed increased prosperity during the 10th century. Abd ar-Rahman III united al-Andalus and brought the Christian kingdoms of the north under control by force and through diplomacy. Abd ar-Rahman III stopped the Fatimid advance into Morocco and al-Andalus in order to prevent a future invasion. The plan for a Fatimid invasion was thwarted when Abd ar-Rahman III secured Melilla in 927, Ceuta in 931, and Tangier in 951.[9] This period of prosperity was marked by increasing diplomatic relations with Berber tribes in North Africa, Christian kings from the north, and with France, Germany and Constantinople.[11] The caliphate became very profitable during the reign of Abd ar-Rahman III, by increasing the public revenue to 6,245,000 dinars from Abd ar-Rahman II. The profits made during this time were divided into three parts: the payment of the salaries and maintenance of the army, the preservation of public buildings, and the needs of the caliph.[9] The death of Abd ar-Rahman III led to the rise of his 46-year-old son, Al-Hakam II, in 961. Al-Hakam II continued his father's policy toward Christian kings and North African rebels. Al-Hakam's reliance on his advisers was greater than his father's because the previous prosperity under Abd ar-Rahman III allowed al-Hakam II to let the caliphate run by itself. This style of rulership suited al-Hakam II since he was more interested in his scholarly and intellectual pursuits than ruling the caliphate. The caliphate was at its intellectual and scholarly peak under al-Hakam II.[12][13]

Fall

The death of al-Hakam II in 976 marked the beginning of the end of the caliphate. Before his death, al-Hakam named his only son Hisham II successor. Although the 10-year-old child was ill-equipped to be caliph, Al-Mansur Ibn Abi Aamir (top adviser to al-Hakam, also known as Almanzor), who had sworn an oath of obedience to Hisham II, pronounced him caliph. Almanzor had great influence over Subh, the mother and regent of Hisham II. Almanzor, along with Subh, isolated Hisham in Córdoba while systematically eradicating opposition to his own rule, allowing Berbers from Africa to migrate to al-Andalus to increase his base of support.[14] While Hisham II was caliph, he was merely a figurehead.[15] He, his son Abd al-Malik (al-Muzaffar, after his 1008 death) and his brother (Abd al-Rahman) retained the power nominally held by Caliph Hisham. However, during a raid on the Christian north a revolt tore through Córdoba and Abd al-Rahman never returned.[16][17]

The title of caliph became symbolic, without power or influence. The death of Abd al-Rahman Sanchuelo in 1009 marked the beginning of the Fitna of al-Andalus, with rivals claiming to be the new caliph, violence sweeping the caliphate, and intermittent invasions by the Hammudid dynasty.[13] Beset by factionalism, the caliphate crumbled in 1031 into a number of independent taifas, including the Taifa of Córdoba, Taifa of Seville and Taifa of Zaragoza. The last Córdoban Caliph was Hisham III (1027–1031).

Culture

Córdoba was the cultural centre of al-Andalus.[18] Mosques, such as the Great Mosque, were the focus of many caliphs' attention. The caliph's palace, Medina Azahara is on the outskirts of the city, where an estimated 10,000 laborers and artisans worked for decades on the palace, constructing the decorated buildings and courtyards filled with fountains and airy domes.[19] Córdoba was also the intellectual centre of al-Andalus, with translations of ancient Greek texts into Arabic, Latin and Hebrew. During the reign of al-Hakam II, the royal library possessed an estimated 500,000 volumes.[13][20] For comparison, the Abbey of Saint Gall in Switzerland contained just over 100 volumes.[13] The university in Córdoba became the most celebrated in the world. It was attended by Christian students from all Western Europe, as well as Muslim students. The university produced one hundred and fifty authors. Other universities and libraries were scattered through Spain during this golden age.[21] During the Caliphate period, relations between Jews and Arabs were cordial; Jewish stonemasons helped build the columns of the Great Mosque.

Advances in science, history, geography, philosophy, and language occurred during the Caliphate.[22] Al-Andalus was subject to eastern cultural influences as well. The musician Ziryab is credited with bringing hair and clothing styles, toothpaste, and deodorant from Baghdad to the Iberian peninsula.[23]

Economy

The economy of the caliphate was diverse and successful, with trade predominating. Muslim trade routes connected al-Andalus with the outside world via the Mediterranean. Industries revitalized during the caliphate included textiles, ceramics, glassware, metalwork, and agriculture. The Arabs introduced crops such as rice, watermelon, banana, eggplant and hard wheat. Fields were irrigated with water wheels. Some of the most prominent merchants of the caliphate were Jews. Jewish merchants had extensive networks of trade that stretched the length of the Mediterranean Sea. Since there was no international banking system at the time, payments relied on a high level of trust, and this level of trust could only be cemented through personal or family bonds, such as marriage. Jews from al-Andalus, Cairo, and the Levant all intermarried across borders. Therefore, Jewish merchants in the caliphate had counterparts abroad that were willing to do business with them.[24]

Religion

The caliphate had an ethnically, culturally, and religiously diverse society. A minority of ethnic Muslims of Arab descent occupied the priestly and ruling positions, another Muslim minority were primarily soldiers and native Hispano-Gothic converts (who comprised most of the Muslim minority) were found throughout society. Jews comprised about ten percent of the population: little more numerous than the Arabs and about equal in numbers to the Berbers. They were primarily involved in business and intellectual occupations. The indigenous Christian Mozarab majority were Catholic Christians of the Visigothic rite, who spoke a variant of Latin close to Spanish, Portuguese or Catalan with an Arabic influence. The Mozarabs were the lower strata of society, heavily taxed with few civil rights and culturally influenced by the Muslims. Ethnic Arabs occupied the top of the social hierarchy; Muslims had a higher social standing than Jews, who had a higher social standing than Christians. Christians and Jews were considered dhimmis, required to pay jizya (a tax for the wars against Christian kingdoms in the north).[25]

The word of a Muslim was valued more than that of a Christian or Jew in court. Some offenses were harshly punished when a Jew or Christian was the perpetrator against a Muslim even if the offenses were permitted when the perpetrator was a Muslim and the victim a non-Muslim. Half of the population in Córdoba is reported to have been Muslim by the 10th century, with an increase to 70 percent by the 11th century. That was due less to local conversion than to Muslim immigration from the rest of the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. Combined with the mass expulsions of Christians from Córdoba after a revolt in the city, that explains why, during the caliphate, Cordoba was the greatest Muslim centre in the region. Jewish immigration to Córdoba also increased then. Christians saw their status decline from their rule under the Visigoths, meanwhile the status of Jews improved during the Caliphate. While Jews were persecuted under the Visigoths, Jewish communities benefited from Umayyad rule by obtaining more freedom, affluence and a higher social standing.[24]

Population

According to Thomas Glick, "Despite the withdrawal of substantial numbers during the drought and famine of the 750's, fresh Berber migration from North Africa was a constant feature of Andalusi history, increasing in tempo in the tenth century. Hispano-Romans who converted to Islam, numbering six or seven millions, comprised the majority of the population and also occupied the lowest rungs on the social ladder."[26][27] It is also estimated that the capital city held around 450,000 people, making it the largest city in Europe at the time.[28]

List of rulers

According to historians, the emirs and caliphs comprising the Umayyad dynasty in Al-Andalus were the sons of concubine slaves (almost all Iberians from the north of the peninsula). The founder of the dynasty, Abd ar-Rahman I, was the son of a Berber woman; his son (and successor as emir) had a Spanish mother.[29] As such, the genome of Hisham II, tenth ruler of the Umayyad dynasty, "would have mostly originated from the Iberian Peninsula and would not be more than 0.1% of Arab descent, although the Y chromosome would still be of fully Arab origin".[30][31]

Umayyad Caliphs of Córdoba

- Abd ar-Rahman III, as caliph, 929–961

- Al-Hakam II, 961–976

- Hisham II, 976–1008

- Muhammad II, 1008–1009

- Sulayman II, 1009–1010

- Hisham II, restored, 1010–1012

- Sulayman II, restored, 1012–1016

- al-Mu'iti, rival in Dénia, 1014–1016

- Abd ar-Rahman IV, 1017

Hammudid Caliphs of Córdoba

- Ali ibn Hammud al-Nasir, 1016–1018

- Al-Qasim ibn Hammud al-Ma'mu, 1018–1021

- Yahya ibn Ali ibn Hammud al-Mu'tali, 1021–1023

- Al-Qasim ibn Hammud al-Ma'mu, 1023 (restored)

Umayyad Caliphs of Córdoba (restored)

- Abd ar-Rahman V, 1023–1024

- Muhammad III, 1024–1025

- Interregnum of Yahya ibn Ali ibn Hammud al-Mu'tali, 1025–1026

- Hisham III, 1026–1031

See also

- Caliphate

- Emirate of Córdoba

- History of Islam

- History of Gibraltar

- History of Algeria

- History of Portugal

- History of Morocco

- History of Spain

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- Martyrs of Córdoba

- Septimania timeline

- Umayyad conquest of Hispania

Notes and references

- Azizur Rahman, Syed (2001). The Story of Islamic Spain (snippet view). New Delhi: Goodword Books. p. 129. ISBN 978-81-87570-57-8. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

[Emir Abdullah died on] 16 Oct., 912 after 26 years of inglorious rule leaving his fragmented and bankrupt kingdom to his grandson ‘Abd ar-Rahman. The following day, the new sultan received the oath of allegiance at a ceremony held in the "Perfect salon" (al-majils al-kamil) of the Alcazar.

- Taagepera, Rein (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 495. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Barton, Simon (2004). A History of Spain. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 38. ISBN 0333632575.

- Chejne, Anwar G. (1974). Muslim Spain: Its History and Culture. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press. pp. 43–49. ISBN 0816606889.

- 1968, Hughes, Aaron W. (2013-04-09). Muslim identities : an introduction to Islam. New York. p. 108. ISBN 9780231531924. OCLC 833763900.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Barton, 37.

- D., Stanton, Charles (2015-06-30). Medieval maritime warfare. Barnsley, South Yorkshire. p. 111. ISBN 9781473856431. OCLC 905696269.

- Barton, 38.

- O'Callaghan, J. F. (1983). A History of Medieval Spain. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 119.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1993). The Medieval Spains. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0521394368.

- Chejne, 35.

- Chejne, 37–38.

- Catlos, Brain A. (2014). Infidel Kings and Unholy Wars: Faith, Power, and Violence in the Age of Crusades and Jihad. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. p. 30.

- Chejne, 38–40.

- Catlos, Brain A. (2014). Infidel Kings and Unholy Wars: Faith, Power, and Violence in the Age of Crusades and Jihad. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. p. 23. ISBN 9780374712051.

- Chejne, 42–43.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1993). The Medieval Spains. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 0521394368.

- Barton, 40–41.

- Karabell, Zachary (2007). Peace be upon you : the story of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish coexistence (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9781400043682. OCLC 71810014.

- "Information processing". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Francis Preston Venable, A Short History of Chemistry (1894) p. 21.

- Barton, 42.

- Golden age of the Moor. Van Sertima, Ivan. New Brunswick, U.S.A.: Transaction Publishers. 1992. pp. 267. ISBN 1560005815. OCLC 25416243.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Karabell, Zachary (2007). Peace Be Upon You: The Story of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish Coexistence. New York: Albert A. Knopf. p. 70.

- "This day, Mary 15, in Jewish history". Cleveland Jewish News.

- Glick 2005, p. 202.

- "The rate of conversion is slow until the tenth century (less than one-quarter of the eventual total number of converts had been converted); the explosive period coincides closely with the reign of 'Abd al-Rahman III (912–961); the process is completed (eighty percent converted) by around 1100. The curve, moreover, makes possible a reasonable estimate of the religious distribution of the population. Assuming that there were seven million Hispano-Romans in the peninsula in 711 and that the numbers of this segment of the population remained level through the eleventh century (with population growth balancing out Christian migration to the north), then by 912 there would have been approximately 2.8 million indigenous Muslims (muwalladûn) plus Arabs and Berbers. At this point Christians still vastly outnumbered Muslims. By 1100, however, the number of indigenous Muslims would have risen to a majority of 5.6 million.", (Glick 2005, pp. 23-24)

- Tertius Chandler, Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census, Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1987. ISBN 0-88946-207-0. Figures in main tables are preferentially cited. Part of Chandler's estimates are summarized or modified at The Institute for Research on World-Systems; Largest Cities Through History by Matt T. Rosenberg; or The Etext Archives Archived 2008-02-11 at the Wayback Machine. Chandler defined a city as a continuously built-up area (urban) with suburbs but without farmland inside the municipality.

- Guichard, P. (1976). Al-Andalus: Estructura antropológica de una sociedad islámica en Occidente. Barcelona: Barral Editores. ISBN 8421120166.

- Ambrosio, B.; Hernandez, C.; Noveletto, A.; Dugoujon, J. M.; Rodriguez, J. N.; Cuesta, P.; Fortes-Lima, C.; Caderon, R. (2010). "Searching the peopling of the Iberian Peninsula from the perspective of two Andalusian subpopulations: a study based on Y-chromosome haplogroups J and E". Collegium Antropologicum. 34 (4): 1215–1228. PMID 21874703.

- http://hrcak.srce.hr/file/94109

Bibliography

- Ambrosio, B.; Hernandez, C.; Noveletto, A.; Dugoujon, J. M.; Rodriguez, J. N.; Cuesta, P.; Fortes-Lima, C.; Caderon, R. (2010). "Searching the peopling of the Iberian Peninsula from the perspective of two Andalusian subpopulations: a study based on Y-chromosome haplogroups J and E". Collegium Antropologicum 34 (4): 1215–1228.

- Barton, Simon (2004). A History of Spain. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 0333632575.

- Chejne, Anwar G. (1974). Muslim Spain: Its History and Culture. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816606889.

- Glick, Thomas F. (1999: 2005). Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages. The Netherlands: Brill.

- Guichard, P. (1976). Al-Andalus: Estructura antropológica de una sociedad islámica en Occidente. Barcelona: Barral Editores. ISBN 8421120166

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1993). The Medieval Spains. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521394368.

Further reading

- Fletcher, Richard (2001). Moorish Spain (Hardcover ed.). Orion. ISBN 1-84212-605-9.