Maqam (shrine)

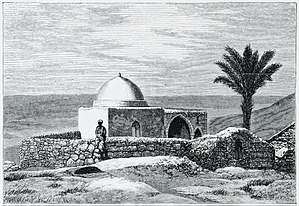

A Maqām (Arabic: مقام) is a shrine built on the site associated with a Muslim saint or religious figure, usually his or her tomb. It is a funeral construction, usually small, cubic-shaped and topped with a dome.

The maqams of Palestine were considered highly significant to the field of biblical archaeology, as their names were used in the 18th and 19th centuries to identify much of biblical geography.[1] According to Claude Reignier Conder's description in 1877, the Palestinian locals attached "more importance to the favour and protection of the village Mukam than to Allah himself, or to Mohammed his prophet".[2]

Etymology

From Arabic literally "a place" or "station."[3] It is used to denote a "sanctuary", such as a commemorative burial shrine or an actual tomb.[3] Its meaning can be restricted only to built structures that can be entered at such sites.[3] The literal meaning of maqam is "the place where one stands."[3] Such name for a holy tomb is mostly used in Syria and Palestine.

There is a form Mukam in the essays of European travellers of the 19th century; as well as words Waly, Wely (Arabic: ويلي — tomb of a saint), Mazar (mausoleum), Mashhad.

Due to their cubic shape, these constructions were also called Kubbeh, Kubbi, Qubba the same way as the major sacred site Kaaba in Mecca. In Maghreb similar tombs are known as Marabout, in Turkic-speaking Muslim countries as Türbe, Dürbe, Aziz and in Iranian-speaking countries — Dargah.

Construction and purpose

The most popular type of maqams is a single chamber square building topped with a dome, in the middle of which there is a stone cenotaph,[4] though the bodies of holy men themselves were buried below the ground level. In the south wall of the maqam, facing Mecca, there is usually a small mihrab decorated with inscriptions and floral ornament. The entrance to the chamber is mostly at the north wall. In the other arched walls there are usually small windows.

The dome is often situated by an ancient carob or oak tree or a spring or rock cut water cistern.[5][6] The positioning of maqams on or near these nautral features is seen as indicative of ancient worship practices adapted by the local population and associated with Muslim saints.[7] Ali Qleibo, a Palestinian anthropologist, states that this built evidence constitutes "an architectural testimony to Christian/Moslem Palestinian religious sensibility and its roots in ancient Semitic religions."[5]

Maqams were dedicated to biblical and quranic, real or mythical, male and female figures from ancient times to the time of the Arab conquest or even late Ottoman rule.[8] The maqams are not always supposed to stand over the tombs of the saints to whom they are dedicated. A cenotaph is indeed almost always to be found there, but often they are regarded merely as "stations."

There are also bigger maqams, consisting of two, three or four chambers:[9] prayer chamber, entrance hall, zawiya or a room for pilgrims to have a rest. Big maqams have two or three similar domes. In times of old, the dome was decorated by a metal spire with a crescent, but nowadays such decoration is rare.

A sacred tree was planted near maqams, mostly — a palm tree, oak or sycomore. There was also a well or spring.

Candelabras and lamps are hanging in an active maqam, a cenotaph is covered by a quilt (usually a green one), praying rugs are spread on the floor in front of the mihrab.

It is in worship at these shrines that the religion of the peasantry consists. Moslem by profession, they often spend their lives without entering a mosque, and attach more importance to the favour and protection of the village Мukam than to Allah himself, or to Mohammed his prophet.[10]

As a rule, maqams were built on the top of the hills or at the crossroads, and besides their main function — shrine and prayer place, they also served as a guard point and a guiding landmark for travelers and caravans. Over the years, new burial places appeared near maqams; it was considered as honour to be buried next to a saint. Big cemeteries formed around many Muslim sanctuaries.

Almost every village in Palestine has a wali, a patron saint, whom people, predominantly rural peasants, would call upon for help at his or her associated sanctuary.[11] While wali can refer to both the saint and sanctuary, a sanctuary for a common saint is more precisely known as a maqam.[12]

History

Early Islam disapproved worshipping of holy men and their burial places, considering it a sort of idolatry. But it was Shiites who started to build sumptuous tombs for their deceased leaders — imams and sheikhs, and turned those tombs into religious objects. Very soon Sunnis followed their example. Arab travellers and geographers ‘Ali al-Harawi, Yaqut al-Hamawi and others described in their essays many Christian and Muslim shrines in Syria, Palestine and Egypt.

During the times of Mamluk dynasty, monumental tombs were built for Muslim holy men, scientists and theologists, some of these tombs have come down to present times. The major part of them is located in Egypt, and some parts are also in Syria and Palestine. These are namely the famous Rachel's Tomb in Bethlehem (though the burial place of matriarch Rachel was worshipped even before), the splendid mausoleum of Abu Hurairah in Yavne[13] and the maqam of sheikh Abu ‘Atabi in Al-Manshiyya, Acre.

In the Ottoman Empire times, maqams were constructed everywhere, and old sanctuaries were taken under restoration. New buildings were not as monumental and pompous as before, and looked quite unpretentious. In Turkish period, maqams had simple construction and almost no architectural décor.

Mosques were uncommon in Palestinian villages until the late 19th century, but practically every village had at least one maqam which served as sites of worship in the Palestinian folk Islam popular in the countryside over the centuries.[11][6] Christians and Jews also held some of the maqams to be holy, such as that of Nabi Samwil.[12] In the period of Ottoman rule over Palestine, most of these sites were visited collectively by members of all three faiths who often travelled together with provisions for a multi-day journey; by the Mandate Palestine period, politicization led to segregation.[8] Some maqams, like Nabi Rubin and Nabi Musa among others, were also the focus of seasonal festivals (mawsims) that thousands would attend annually.

There is, however, in nearly every village, a small whitewashed building with a low dome — the "mukam," or "place," sacred to the eyes of the peasants. In almost every landscape such a landmark gleams from the top of some hill, just as, doubtless, something of the same kind did in the old Canaanite ages.[14]

The period of Mandatory Palestine has become the last time of maqams prosperity. Dilapidated Muslims shrines were restored and also new ones built. The British built over and donated to Bedouins the Maqam of sheikh Nuran, which was damaged during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. This maqam was in the battle epicenter during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. After having captured it, Israeli soldiers turned it into a watch and firing point. Since that time the maqam of sheikh Nuran is a memorial of the Israel Defense Forces.

After the State of Israel was formed, numerous Muslim shrines were privatized by Jewish and turned them into their own religious shrines. It concerned the mausoleum of sheikh Abu Hurairah, it which has become the tomb of Rabban Gamaliel II in Yavne;[15] the Maqam with seven domes of Imam ‘Ali in Yazur has turned into a synagogue in Azor; the mazar of Sitt Sakina (Sukeyna) has become Rachel's tomb, the spouse of Rabbi Akiva in Tiberias; the Maqam of sheikh al-Gharbawi — the tomb of Mattathias; the tomb of Nabi Sheman near the Junction Eyal, which has been turned into the tomb of Simeon (son of Jacob). The privatization of muslim shrines is still in process.

In ancient times, all maqams with the domes were coloured in white.[16] Recently Palestinian and Israeli Arabs got used to colour the domes of their shrines in green (the colour of Islam). On the territory of Israel battle for one or another shrine resulted in the war of colours, as it was called in press.[17] While privatizing Muslim shrines, religious Jewish paint the dome in blue or white and install Jewish symbols, and Muslims, when coming back, remove Jewish symbols and paint the dome in green.

Some famous Palestinian maqams

No more than 300 maqams out of 800 existing in Palestine in 1948, came down to present times, half of them are on the territory of Israel, the remainder in the Palestinian Authority. According to another source, the number of Palestinian maqams left is 184, with only 70 on the Israeli territories.[18] Claude Reignier Conder identified seven types of Palestinian muqam in 1877:[19]

- Biblical characters: "These are, no doubt, generally the oldest, and can often be traced back to Jewish tradition"

- Christian sites venerated by the Moslem peasantry: "not always distinguishable from the first class, but often traceable to the teaching of the monasteries or to monkish sites"

- Other native heroes or deities: "perhaps sometimes the most ancient sites of all"

- Later and known historic characters

- Saints named from the place where they occur, or having appellations connected with traditions concerning them

- Sacred sites not connected with personal names: "Some of these are of the greatest value"

- Ordinary Moslem names which may be of any date

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palestinian maqams. |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jordanian maqams. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tombs of Muslim saints in Egypt. |

References

- Conder, 1877, p. 89: "...the local sanctuaries scattered over the country, a study which is also of no little importance in relation to the ancient topography of Palestine, as is shown by the various sites which have been recovered by means of the tradition of sacred tombs preserved after the name of the site itself had been lost."

- Conder, 1877, pp. 89-90: "In their religious observances and sanctuaries we find, as in their language, the true history of the country. On a basis of polytheistic faith which most probably dates back to pre-Israelite times, we find a growth of the most heterogeneous description: Christian tradition, Moslem history and foreign worship are mingled so as often to be entirely indistinguishable, and the so-called Moslem is found worshipping at shrines consecrated to Jewish, Samaritan, Christian, and often Pagan memories. It is in worship at these shrines that the religion of the peasantry consists. Moslem by profession, they often spend their lives without entering a mosque, and attach more importance to the favour and protection of the village Mukam than to Allah himself, or to Mohammed his prophet... The reverence shown for these sacred spots is unbounded. Every fallen stone from the building, every withered branch of the tree, is carefully preserved. "

- Prochazka 2010, p. 112

- McCown, 1921, p. 50

- Dr. Ali Qleibo (28 July 2007). "Palestinian Cave Dwellers and Holy Shrines: The Passing of Traditional Society". This Week in Palestine. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- Kark 2001, p. 260

- "Levant". 1996.

- Pappe 2006, p. 78

- Canaan, 1927, p. 47: "The more important the holy man, the greater the complexity of the building. Prophets (anbiā) enjoy the largest maqams."

- Conder, 1877, p. 89

- Hourani 1993, pp. 470–471

- Sharon 1999, p. 142

- Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau describes this monument as follows: "At Yebna we pitched our tent near the wely of Abu Horeira. Inside this we noticed numerous fragments of marble, several stones with the medieval tool-marking, and two marble columns surmounted by their capitals. The outside of the building is rather a picturesque sight, with its lewain of three arches, its cupolas and its courtyard planted with fine trees." —Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, Vol. II. pp. 167–168

- Geikie, 1888, vol. I, p. 578

- Breger, M. J., Reiter, Y. and Hammer, L. (2010) Holy Places in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Confrontation and Co-existence. London and N.–Y., 2010. pp. 79–80.

- Conder, 1877, p. 90: "The white dome of the Mukam is the most conspicuous object in a Syrian village."

- The War of colors on the shrine of Sheikh Simeon (in arabic).

- Frantzman, S. J. and Bar, D. (2013) Mapping Muslim Sacred Tombs in Palestine During the Mandate Period // "Levant", 2013, Vol. 45, No 1. P. 109–110.

- Conder, 1877, p. 91

Bibliography

- Benveniśtî, M. (2000). Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948 (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21154-5.

- Canaan, T. (1927). Mohammedan Saints and Sanctuaries in Palestine. London: Luzac & Co.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1896). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873-1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. 2. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Conder, C.R. (1877). "The Moslem Mukams". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 9 (3): 89–103. doi:10.1179/peq.1877.9.3.89.

- Frantzman, S.J. and Bar, D. (2013) Mapping Muslim Sacred Tombs in Palestine During the Mandate Period. // "Levant", 2013, Vol. 45, No 1. P. 96–111.

- Geikie, J.C. (1888). The Holy Land and the Bible. A Book of scripture illustrations gathered in Palestine. I. New York.

- Hourani, A.; Khoury, P.S.; Wilson, Mary Christina (1993). The Modern Middle East: a reader. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520082403.

- Kark, R.; Oren-Nordheim, Michal (2001). Jerusalem and its environs: quarters, neighborhoods, villages, 1800-1948 (Illustrated ed.). Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2909-2.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains:The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- McCown, C.C. (1921). "Muslim Shrines in Palestine". Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 2–3: 47–79.

- Pappé, I. (2006-07-31). A history of modern Palestine: one land, two peoples (2, illustrated, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780521683159.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Procházka-Eisl, Gisela; Procházka, Stephan (2010). The Plain of Saints and Prophets: The Nusayri-Alawi Community of Cilicia (Southern Turkey) and Its Sacred Places. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447061780.

- Sharon, M. (1999). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, B-C. 2. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11083-6.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)