Tennessee

Tennessee (/ˌtɛnəˈsiː/ (![]()

Tennessee | |

|---|---|

| State of Tennessee | |

| Nickname(s): The Volunteer State | |

| Motto(s): Agriculture and Commerce | |

| Anthem: Nine songs | |

Map of the United States with Tennessee highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Southwest Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | June 1, 1796 (16th) |

| Capital (and largest city) | Nashville[1] |

| Largest metro | Greater Nashville |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Bill Lee (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Randy McNally (R) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Tennessee Supreme Court |

| U.S. senators | Lamar Alexander (R) Marsha Blackburn (R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 7 Republicans 2 Democrats (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 42,143 sq mi (109,247 km2) |

| • Land | 41,217 sq mi (106,846 km2) |

| • Water | 926 sq mi (2,401 km2) 2.2% |

| Area rank | 36th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 440 mi (710 km) |

| • Width | 120 mi (195 km) |

| Elevation | 900 ft (270 m) |

| Highest elevation | 6,643 ft (2,025 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 178 ft (54 m) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Total | 6,829,174[4] |

| • Rank | 16th |

| • Density | 159.4/sq mi (61.5/km2) |

| • Density rank | 20th |

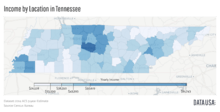

| • Median household income | $52,340[5] |

| • Income rank | 42nd |

| Demonym(s) | Tennessean Big Bender (archaic) Volunteer (historical significance) |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language | Language spoken at home[6] |

| Time zones | |

| East Tennessee | UTC−05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| Middle and West | UTC−06:00 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | TN |

| ISO 3166 code | US-TN |

| Trad. abbreviation | Tenn. |

| Latitude | 34°59′ N to 36°41′ N |

| Longitude | 81°39′ W to 90°19′ W |

| Website | www |

| Tennessee state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Amphibian | Tennessee cave salamander |

| Bird | Mockingbird Bobwhite quail |

| Butterfly | Zebra swallowtail |

| Fish | Channel catfish Smallmouth bass |

| Flower | Iris Passion flower Tennessee echinacea |

| Insect | Firefly Lady beetle Honey bee |

| Mammal | Tennessee Walking Horse Raccoon |

| Reptile | Eastern box turtle |

| Tree | Tulip poplar Eastern red cedar |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Milk |

| Dance | Square dance |

| Firearm | Barrett M82 |

| Food | Tomato |

| Fossil | Pterotrigonia (Scabrotrigonia) thoracica |

| Gemstone | Tennessee River pearl |

| Mineral | Agate |

| Poem | "Oh Tennessee, My Tennessee" by William Lawrence |

| Rock | Limestone |

| Slogan | "Tennessee—America at its best" |

| Tartan | Tennessee State Tartan |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2002 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

The state of Tennessee is rooted in the Watauga Association, a 1772 frontier pact generally regarded as the first constitutional government west of the Appalachians.[11] What is now Tennessee was initially part of North Carolina, and later part of the Southwest Territory. Tennessee was admitted to the Union as the 16th state on June 1, 1796. Tennessee was the last state to leave the Union and join the Confederacy at the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861. Occupied by Union forces from 1862, it was the first state to be readmitted to the Union at the end of the war.[12]

Tennessee furnished more soldiers for the Confederate Army than any other state besides Virginia, and more soldiers for the Union Army than the rest of the Confederacy combined.[12] Beginning during Reconstruction, it had competitive party politics, but a Democratic takeover in the late 1880s resulted in passage of disenfranchisement laws that excluded most blacks and many poor whites from voting. This sharply reduced competition in politics in the state until after passage of civil rights legislation in the mid-20th century.[13] In the 20th century, Tennessee transitioned from an agrarian economy to a more diversified economy, aided by massive federal investment in the Tennessee Valley Authority and, in the early 1940s, the city of Oak Ridge. This city was established just outside of Knoxville to house the Manhattan Project's uranium enrichment facilities, helping to build the world's first atomic bombs, two of which were dropped on Imperial Japan near the end of World War II. After the war, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory became and remains a key center for scientific research. In 2016, the element tennessine was named for the state, largely in recognition of the roles played by Oak Ridge, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Tennessee in the element’s discovery.[14]

Tennessee's major industries include agriculture, manufacturing, and tourism. Poultry, soybeans, and cattle are the state's primary agricultural products,[15] and major manufacturing exports include chemicals, transportation equipment, and electrical equipment.[16] The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the nation's most visited national park, is located in the eastern part of the state, and a section of the Appalachian Trail roughly follows the Tennessee–North Carolina border.[17] Other major tourist attractions include the Tennessee Aquarium and Chattanooga Choo-Choo Hotel in Chattanooga; Dollywood in Pigeon Forge; Ripley's Aquarium of the Smokies and Ober Gatlinburg in Gatlinburg; the Parthenon, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, and Ryman Auditorium in Nashville; the Jack Daniel's Distillery in Lynchburg; Elvis Presley's Graceland residence and tomb, the Memphis Zoo, the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis; and Bristol Motor Speedway in Bristol.

Etymology

The earliest variant of the name that became Tennessee was recorded by Captain Juan Pardo, the Spanish explorer, when he and his men passed through an American Indian village named "Tanasqui" in 1567 while traveling inland from South Carolina. In the early 18th century, British traders encountered a Cherokee town named Tanasi (or "Tanase") in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee. The town was located on a river of the same name (now known as the Little Tennessee River), and appears on maps as early as 1725. It is not known whether this was the same town as the one encountered by Juan Pardo, although recent research suggests that Pardo's "Tanasqui" was located at the confluence of the Pigeon River and the French Broad River, near modern Newport.[18]

The meaning and origin of the word are uncertain. Some accounts suggest it is a Cherokee modification of an earlier Yuchi word. It has been said to mean "meeting place", "winding river", or "river of the great bend".[19][20] According to ethnographer James Mooney, the name "can not be analyzed" and its meaning is lost.[21]

The modern spelling, Tennessee, is attributed to James Glen, the governor of South Carolina, who used this spelling in his official correspondence during the 1750s. The spelling was popularized by the publication of Henry Timberlake's "Draught of the Cherokee Country" in 1765. In 1788, North Carolina created "Tennessee County", the third county to be established in what is now Middle Tennessee. (Tennessee County was the predecessor to present-day Montgomery and Robertson counties.) When a constitutional convention met in 1796 to organize a new state out of the Southwest Territory, it adopted "Tennessee" as the name of the state.

Nickname

Tennessee is known as The Volunteer State, a nickname some claimed was earned during the War of 1812 because of the prominent role played by volunteer soldiers from Tennessee, especially during the Battle of New Orleans.[22] Other sources differ on the origin of the state nickname; according to The Columbia Encyclopedia,[23] the name refers to volunteers for the Mexican–American War from 1846 to 1848. This explanation is more likely, because President Polk's call for 2,600 nationwide volunteers at the beginning of the Mexican–American War resulted in 30,000 volunteers from Tennessee alone, largely in response to the death of Davy Crockett and appeals by former Tennessee Governor and then Texas politician, Sam Houston.[24]

Geography

Tennessee borders eight other states: Kentucky and Virginia to the north; North Carolina to the east; Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi on the south; Arkansas and Missouri on the Mississippi River to the west. Tennessee is tied with Missouri as the state bordering the most other states. The state is trisected by the Tennessee River.

The highest point in the state is Clingmans Dome at 6,643 feet (2,025 m).[25] Clingmans Dome, which lies on Tennessee's eastern border, is the highest point on the Appalachian Trail, and is the third highest peak in the United States east of the Mississippi River. The state line between Tennessee and North Carolina crosses the summit. The state's lowest point is the Mississippi River at the Mississippi state line: 178 feet (54 m). The geographical center of the state is located in Murfreesboro.

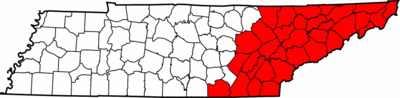

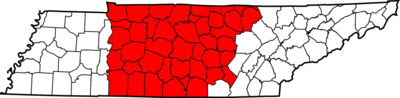

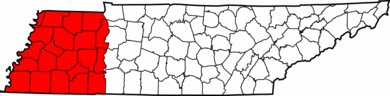

The state of Tennessee is geographically, culturally, economically, and legally divided into three Grand Divisions: East Tennessee, Middle Tennessee, and West Tennessee. The state constitution allows no more than two justices of the five-member Tennessee Supreme Court to be from one Grand Division and a similar rule applies to certain commissions and boards.

Tennessee features six principal physiographic regions: the Blue Ridge, the Appalachian Ridge and Valley Region, the Cumberland Plateau, the Highland Rim, the Nashville Basin, and the Gulf Coastal Plain. Tennessee is home to the most caves in the United States, with more than ten thousand documented.[26]

About half the state is in the Tennessee Valley drainage basin of the Tennessee River.[27] Approximately the northern half of Middle Tennessee, including Nashville and Clarksville, and a small portion of East Tennessee is in the Cumberland River basin.[28] A small part of north-central Tennessee in Sumner, Macon, and Clay counties is in the Green River watershed.[29] All three of these basins are tributaries of the Ohio River watershed. Most of West Tennessee is in the Lower Mississippi River watershed.[30] The entirety of the state is in the Mississippi River watershed, except for a small area in Bradley and Polk counties traversed by the Conasauga River, which is part of the Mobile Bay watershed.[31]

East Tennessee

The Blue Ridge area lies on the eastern edge of Tennessee, which borders North Carolina. This region of Tennessee is characterized by the high mountains and rugged terrain of the western Blue Ridge Mountains, which are subdivided into several subranges, namely the Great Smoky Mountains, the Bald Mountains, the Unicoi Mountains, the Unaka Mountains and Roan Highlands, and the Iron Mountains.

The average elevation of the Blue Ridge area is 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above sea level. Clingmans Dome, the state's highest point, is located in this region. The Blue Ridge area was never more than sparsely populated, and today much of it is protected by the Cherokee National Forest, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and several federal wilderness areas and state parks.

Stretching west from the Blue Ridge for approximately 55 miles (89 km) is the Ridge and Valley region, in which numerous tributaries join to form the Tennessee River in the Tennessee Valley. This area of Tennessee is covered by fertile valleys separated by wooded ridges, such as Bays Mountain and Clinch Mountain. The western section of the Tennessee Valley, where the depressions become broader and the ridges become lower, is called the Great Valley. In this valley are numerous towns and two of the region's three urban areas, Knoxville, the third largest city in the state, and Chattanooga, the fourth largest city in the state. The third urban area, the Tri-Cities, comprising Bristol, Johnson City, and Kingsport and their environs, is located to the northeast of Knoxville.

The Cumberland Plateau rises to the west of the Tennessee Valley; this area is covered with flat-topped mountains separated by sharp valleys. The elevation of the Cumberland Plateau ranges from 1,500 to about 2,000 feet (460 to about 610 m) above sea level.

East Tennessee has several important transportation links with Middle and West Tennessee, as well as the rest of the nation and the world, including several major airports and interstates. Knoxville's McGhee Tyson Airport (TYS) and Chattanooga's Chattanooga Metropolitan Airport (CHA), as well as the Tri-Cities' Tri-Cities Regional Airport (TRI), provide air service to numerous destinations. I-24, I-81, I-40, I-75, and I-26 along with numerous state highways and other important roads, traverse the Grand Division and connect Chattanooga, Knoxville, and the Tri-Cities, along with other cities and towns such as Cleveland, Athens, and Sevierville.

Middle Tennessee

West of the Cumberland Plateau is the Highland Rim, an elevated plain that surrounds the Nashville Basin. The northern section of the Highland Rim, known for its high tobacco production, is sometimes called the Pennyroyal Plateau; it is located primarily in Southwestern Kentucky. The Nashville Basin is characterized by rich, fertile farm country and great diversity of natural wildlife.

Middle Tennessee was a common destination of settlers crossing the Appalachians from Virginia in the late 18th century and early 19th century. An important trading route called the Natchez Trace, created and used for many generations by American Indians, connected Middle Tennessee to the lower Mississippi River town of Natchez. The route of the Natchez Trace was used as the basis for a scenic highway called the Natchez Trace Parkway.

Some of the last remaining large American chestnut trees grow in this region. They are being used to help breed blight-resistant trees.

Middle Tennessee is one of the primary state population and transportation centers along with the heart of state government. Nashville (the capital), Clarksville, and Murfreesboro are its largest cities.[32] Interstates 24, 40, 65, and 840 service the Division, with the first three meeting in Nashville.

West Tennessee

West of the Highland Rim and Nashville Basin is the Gulf Coastal Plain, which includes the Mississippi embayment. The Gulf Coastal Plain is, in terms of area, the predominant land region in Tennessee. It is part of the large geographic land area that begins at the Gulf of Mexico and extends north into southern Illinois. In Tennessee, the Gulf Coastal Plain is divided into three sections that extend from the Tennessee River in the east to the Mississippi River in the west.

The easternmost section, about 10 miles (16 km) in width, consists of hilly land that runs along the western bank of the Tennessee River. To the west of this narrow strip of land is a wide area of rolling hills and streams that stretches all the way to the Mississippi River; this area is called the Tennessee Bottoms or bottom land. In Memphis, the Tennessee Bottoms end in steep bluffs overlooking the river. To the west of the Tennessee Bottoms is the Mississippi Alluvial Plain, less than 300 feet (91 m) above sea level. This area of lowlands, flood plains, and swamp land is sometimes referred to as the Delta region. Memphis is the economic center of West Tennessee.

Most of West Tennessee remained Indian land until the Chickasaw Cession of 1818, when the Chickasaw ceded their land between the Tennessee River and the Mississippi River. The portion of the Chickasaw Cession that lies in Kentucky is known today as the Jackson Purchase.

Public lands

Areas under the control and management of the National Park Service include the following:

- Andrew Johnson National Historic Site in Greeneville

- Appalachian National Scenic Trail

- Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area

- Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

- Cumberland Gap National Historical Park

- Foothills Parkway

- Fort Donelson National Battlefield and Fort Donelson National Cemetery near Dover

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park

- Natchez Trace Parkway

- Obed Wild and Scenic River near Wartburg

- Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail

- Shiloh National Cemetery and Shiloh National Military Park near Shiloh

- Stones River National Battlefield and Stones River National Cemetery near Murfreesboro

- Trail of Tears National Historic Trail

Fifty-four state parks, covering some 132,000 acres (530 km2) as well as parts of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and Cherokee National Forest, and Cumberland Gap National Historical Park are in Tennessee. Sportsmen and visitors are attracted to Reelfoot Lake, originally formed by the 1811–12 New Madrid earthquakes; stumps and other remains of a once dense forest, together with the lotus bed covering the shallow waters, give the lake an eerie beauty.

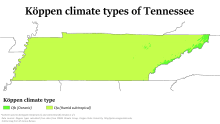

Climate

Most of the state has a humid subtropical climate, with the exception of some of the higher elevations in the Appalachians, which are classified as having a mountain temperate or humid continental climate due to cooler temperatures.[33] The Gulf of Mexico is the dominant factor in the climate of Tennessee, with winds from the south being responsible for most of the state's annual precipitation. Generally, the state has hot summers and mild to cool winters with generous precipitation throughout the year, with highest average monthly precipitation generally in the winter and spring months, between December and April. The driest months, on average, are August to October. On average the state receives 50 inches (130 cm) of precipitation annually. Snowfall ranges from 5 inches (13 cm) in West Tennessee to over 80 inches (200 cm) in the highest mountains in East Tennessee.[34][35]

Summers in the state are generally hot and humid, with most of the state averaging a high of around 90 °F (32 °C) during the summer months. Winters tend to be mild to cool, increasing in coolness at higher elevations. Generally, for areas outside the highest mountains, the average overnight lows are near freezing for most of the state. The highest recorded temperature is 113 °F (45 °C) at Perryville on August 9, 1930, while the lowest recorded temperature is −32 °F (−36 °C) at Mountain City on December 30, 1917.

While the state is far enough from the coast to avoid any direct impact from a hurricane, the location of the state makes it likely to be impacted from the remnants of tropical cyclones which weaken over land and can cause significant rainfall, such as Tropical Storm Chris in 1982 and Hurricane Opal in 1995.[36] The state averages about fifty days of thunderstorms per year, some of which can be severe with large hail and damaging winds. Tornadoes are possible throughout the state, with West and Middle Tennessee the most vulnerable. Occasionally, strong or violent tornadoes occur, such as the devastating April 2011 tornadoes that killed twenty people in North Georgia and Southeast Tennessee.[37] On average, the state has 15 tornadoes per year.[38] Tornadoes in Tennessee can be severe, and Tennessee leads the nation in the percentage of total tornadoes which have fatalities.[39] Winter storms are an occasional problem, such as the infamous Blizzard of 1993, although ice storms are a more likely occurrence. Fog is a persistent problem in parts of the state, especially in East Tennessee.

| Monthly Normal High and Low Temperatures For Various Tennessee Cities (F)[40] | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol | 44/25 | 49/27 | 57/34 | 66/41 | 74/51 | 81/60 | 85/64 | 84/62 | 79/56 | 68/43 | 58/35 | 48/27 |

| Chattanooga | 49/30 | 54/33 | 63/40 | 72/47 | 79/56 | 86/65 | 90/69 | 89/68 | 82/62 | 72/48 | 61/40 | 52/33 |

| Knoxville | 47/30 | 52/33 | 61/40 | 71/48 | 78/57 | 85/65 | 88/69 | 87/68 | 81/62 | 71/50 | 60/41 | 50/34 |

| Memphis | 49/31 | 55/36 | 63/44 | 72/52 | 80/61 | 89/69 | 92/73 | 91/71 | 85/64 | 75/52 | 62/43 | 52/34 |

| Nashville | 46/28 | 52/31 | 61/39 | 70/47 | 78/57 | 85/65 | 90/70 | 89/69 | 82/61 | 71/49 | 59/40 | 49/32 |

Major cities

The capital and largest city is Nashville, though Knoxville, Kingston, and Murfreesboro have all served as state capitals in the past. Nashville's 13-county metropolitan area has been the state's largest since c. 1990. Memphis was the largest city in the state until 2018 when it was surpassed by Nashville. Chattanooga and Knoxville, both in the east near the Great Smoky Mountains, are about a third that size. The city of Clarksville is a fifth significant population center, 45 miles (72 km) northwest of Nashville. Murfreesboro is the sixth-largest city in Tennessee, consisting of 146,900 residents.

History

Early history

The area now known as Tennessee was first inhabited by Paleo-Indians nearly 12,000 years ago.[42] The names of the cultural groups who inhabited the area between first settlement and the time of European contact are unknown, but several distinct cultural phases have been named by archaeologists, including Archaic (8000–1000 BC), Woodland (1000 BC – 1000 AD), and Mississippian (1000–1600 AD), whose chiefdoms were the cultural predecessors of the Muscogee people who inhabited the Tennessee River Valley before Cherokee migration into the river's headwaters.

The first recorded European excursions into what is now called Tennessee were three expeditions led by Spanish explorers, namely Hernando de Soto in 1540, Tristan de Luna in 1559, and Juan Pardo in 1567. Pardo recorded the name "Tanasqui" from a local Indian village, which evolved to the state's current name. At that time, Tennessee was inhabited by tribes of Muscogee and Yuchi people. Possibly because of European diseases devastating the Indian tribes, which would have left a population vacuum, and also from expanding European settlement in the north, the Cherokee moved south from the area now called Virginia. As European colonists spread into the area, the Indian populations were forcibly displaced to the south and west, including all Muscogee and Yuchi peoples, the Chickasaw and Choctaw, and ultimately, the Cherokee in 1838.

The first British settlement in what is now Tennessee was built in 1756 by settlers from the colony of South Carolina at Fort Loudoun, near present-day Vonore. Fort Loudoun became the westernmost British outpost to that date. The fort was designed by John William Gerard de Brahm and constructed by forces under British Captain Raymond Demeré. After its completion, Captain Raymond Demeré relinquished command on August 14, 1757, to his brother, Captain Paul Demeré. Hostilities erupted between the British and the neighboring Overhill Cherokees, and a siege of Fort Loudoun ended with its surrender on August 7, 1760. The following morning, Captain Paul Demeré and a number of his men were killed in an ambush nearby, and most of the rest of the garrison was taken prisoner.[43]

In the 1760s, long hunters from Virginia explored much of East and Middle Tennessee, and the first permanent European settlers began arriving late in the decade. The majority of 18th century settlers were English or of primarily English descent but nearly 20% of them were also Scotch-Irish.[44] These settlers formed the Watauga Association, a community built on lands leased from the Cherokee peoples.

During the American Revolutionary War, Fort Watauga at Sycamore Shoals (in present-day Elizabethton) was attacked (1776) by Dragging Canoe and his warring faction of Cherokee who were aligned with the British Loyalists. These renegade Cherokee were referred to by settlers as the Chickamauga. They opposed North Carolina's annexation of the Washington District and the concurrent settling of the Transylvania Colony further north and west. The lives of many settlers were spared from the initial warrior attacks through the warnings of Dragging Canoe's cousin, Nancy Ward. The frontier fort on the banks of the Watauga River later served as a 1780 staging area for the Overmountain Men in preparation to trek over the Appalachian Mountains, to engage, and to later defeat the British Army at the Battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina.

Three counties of the Washington District (now part of Tennessee) broke off from North Carolina in 1784 and formed the State of Franklin. Efforts to obtain admission to the Union failed, and the counties (now numbering eight) had re-joined North Carolina by 1789. North Carolina ceded the area to the federal government in 1790, after which it was organized into the Southwest Territory. In an effort to encourage settlers to move west into the new territory, in 1787 the mother state of North Carolina ordered a road to be cut to take settlers into the Cumberland Settlements—from the south end of Clinch Mountain (in East Tennessee) to French Lick (Nashville). The Trace was called the "North Carolina Road" or "Avery's Trace", and sometimes "The Wilderness Road" (although it should not be confused with Daniel Boone's "Wilderness Road" through the Cumberland Gap).

Statehood and increasing settlement

Tennessee was admitted to the Union on June 1, 1796 as the 16th state. It was the first state created from territory under the jurisdiction of the United States federal government. Apart from the former Thirteen Colonies only Vermont and Kentucky predate Tennessee's statehood, and neither was ever a federal territory.[45] The Constitution of the State of Tennessee, Article I, Section 31, states that the beginning point for identifying the boundary is the extreme height of the Stone Mountain, at the place where the line of Virginia intersects it, and basically runs the extreme heights of mountain chains through the Appalachian Mountains separating North Carolina from Tennessee past the Native American towns of Cowee and Old Chota, thence along the main ridge of the said mountain (Unicoi Mountain) to the southern boundary of the state; all the territory, lands and waters lying west of said line are included in the boundaries and limits of the newly formed state of Tennessee. Part of the provision also stated that the limits and jurisdiction of the state would include future land acquisition, referencing possible land trade with other states, or the acquisition of territory from west of the Mississippi River.

As more white settlers moved into Tennessee, they came into increasing conflict with Native American tribes. During the administration of U.S. President Martin Van Buren, nearly 17,000 Cherokees, along with approximately 2,000 black slaves owned by Cherokees, were uprooted from their homes between 1838 and 1839 and were forced by the U.S. military to march from "emigration depots" in Eastern Tennessee, such as Fort Cass, toward the more distant Indian Territory west of Arkansas, now the state of Oklahoma.[46] During this relocation an estimated 4,000 Cherokees died along the way west.[47] In the Cherokee language, the event is called Nunna daul Isunyi,"the Trail Where We Cried". The Cherokees were not the only Native Americans forced to emigrate as a result of the Indian removal efforts of the United States, and so the phrase "Trail of Tears" is sometimes used to refer to similar events endured by other American Indian peoples, especially among the "Five Civilized Tribes". The phrase originated as a description of the earlier emigration of the Choctaw nation.

Civil War and Reconstruction

In February 1861, secessionists in Tennessee's state government—led by Governor Isham Harris—sought voter approval for a convention to sever ties with the United States, but Tennessee voters rejected the referendum by a 54–46% margin. The strongest opposition to secession came from East Tennessee, which later tried to form a separate Union-aligned state. Following the Confederate attack upon Fort Sumter in April and Lincoln's call for troops from Tennessee and other states in response, Governor Isham Harris began military mobilization, submitted an ordinance of secession to the General Assembly, and made direct overtures to the Confederate government. The Tennessee legislature ratified an agreement to enter a military league with the Confederate States on May 7, 1861. On June 8, 1861, with people in Middle Tennessee having significantly changed their position, voters approved a second referendum calling for secession, becoming the last state to do so. But the Union-backing State of Scott was also established at this time, and remained a de facto enclave of the United States throughout the war.

Many major battles of the American Civil War were fought in Tennessee—most of them Union victories. Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy captured control of the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers in February 1862. They held off the Confederate counterattack at Shiloh in April. Memphis fell to the Union in June, following a naval battle on the Mississippi River in front of the city. The Capture of Memphis and Nashville gave the Union control of the western and middle sections. This control was confirmed at the Battle of Murfreesboro in early January 1863 and by the subsequent Tullahoma Campaign.

Despite the strength of Unionist sentiment in East Tennessee (with the exception of Sullivan County, which was heavily pro-Confederate), Confederates held the area. The Confederates, led by General James Longstreet, did attack General Burnside's Fort Sanders at Knoxville and lost. It was a big blow to East Tennessee Confederate momentum, but Longstreet won the Battle of Bean's Station a few weeks later. The Confederates besieged Chattanooga during the Chattanooga Campaign in early fall 1863, but were driven off by Grant in November. Many of the Confederate defeats can be attributed to the poor strategic vision of General Braxton Bragg, who led the Army of Tennessee from Perryville, Kentucky, to another Confederate defeat at Chattanooga.

The last major battles came when the Confederates invaded Middle Tennessee in November 1864 and were checked at Franklin, then completely dispersed by George Thomas at Nashville in December. Meanwhile, President Abraham Lincoln appointed displaced senator and native Tennessean Andrew Johnson military governor of the state.

When the Emancipation Proclamation was announced, Tennessee was largely held by Union forces. Thus it was not among the states enumerated in the Proclamation, and the Proclamation did not free any slaves there. Nonetheless, enslaved African Americans escaped to Union lines to gain freedom without waiting for official action. Old and young, men, women, and children camped near Union troops. Thousands of former slaves ended up fighting on the Union side, nearly 200,000 in total across the South.

Tennessee's legislature approved an amendment to the state constitution prohibiting slavery on February 22, 1865.[48] Voters in the state approved the amendment in March.[49] It also ratified the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (abolishing slavery in every state) on April 7, 1865.

In 1864, Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat from Tennessee, was elected Vice President under Abraham Lincoln. He became President after Lincoln's assassination in 1865. Under Johnson's lenient re-admission policy, Tennessee was the first of the seceding states to have its elected members readmitted to the U.S. Congress, on July 24, 1866. Because Tennessee had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, it was the only one of the formerly secessionist states that did not have a military governor during the Reconstruction period.

After the formal end of Reconstruction, the struggle over power in Southern society continued. Through violence and intimidation against freedmen and their allies, White Democrats regained political power in Tennessee and other states across the South in the late 1870s and 1880s. Over the next decade, the state legislature passed increasingly restrictive laws to control African Americans. In 1889 the General Assembly passed four laws described as electoral reform, with the cumulative effect of essentially disfranchising most African Americans in rural areas and small towns, as well as many poor Whites. Legislation included implementation of a poll tax, timing of registration, and recording requirements. Tens of thousands of taxpaying citizens were without representation for decades into the 20th century.[13] Disfranchising legislation accompanied Jim Crow laws passed in the late 19th century, which imposed segregation in the state. In 1900, African Americans made up nearly 24% of the state's population, and numbered 480,430 citizens who lived mostly in the central and western parts of the state.[50]

In 1897, Tennessee celebrated its centennial of statehood (though one year late of the 1896 anniversary) with a great exposition in Nashville. A full-scale replica of the Parthenon was constructed for the celebration, located in what is now Nashville's Centennial Park.

20th century

On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth and final state necessary to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which provided women the right to vote. Disenfranchising voter registration requirements continued to keep most African Americans and many poor whites, both men and women, off the voter rolls.

The need to create work for the unemployed during the Great Depression, a desire for rural electrification, the need to control annual spring flooding and improve shipping capacity on the Tennessee River were all factors that drove the federal creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1933. Through the power of the TVA projects, Tennessee quickly became the nation's largest public utility supplier.

During World War II, the availability of abundant TVA electrical power led the Manhattan Project to locate one of the principal sites for production and isolation of weapons-grade fissile material in East Tennessee. The planned community of Oak Ridge was built from scratch to provide accommodations for the facilities and workers. These sites are now Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the Y-12 National Security Complex, and the East Tennessee Technology Park.

Despite recognized effects of limiting voting by poor whites, successive legislatures expanded the reach of the disfranchising laws until they covered the state. Political scientist V. O. Key, Jr. argued in 1949:

... the size of the poll tax did not inhibit voting as much as the inconvenience of paying it. County officers regulated the vote by providing opportunities to pay the tax (as they did in Knoxville), or conversely by making payment as difficult as possible. Such manipulation of the tax, and therefore the vote, created an opportunity for the rise of urban bosses and political machines. Urban politicians bought large blocks of poll tax receipts and distributed them to blacks and whites, who then voted as instructed.[13]

In 1953 state legislators amended the state constitution, removing the poll tax. In many areas both blacks and poor whites still faced subjectively applied barriers to voter registration that did not end until after passage of national civil rights legislation, including the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[13]

Tennessee celebrated its bicentennial in 1996. With a yearlong statewide celebration entitled "Tennessee 200", it opened a new state park (Bicentennial Mall) at the foot of Capitol Hill in Nashville.

The state has had major disasters, such as the Great Train Wreck of 1918, one of the worst train accidents in U.S. history,[51] and the Sultana explosion on the Mississippi River near Memphis, the deadliest maritime disaster in U.S. history.[52]

21st century

In 2002, businessman Phil Bredesen was elected to become the 48th governor in January 2003. Also in 2002, Tennessee amended the state constitution to allow for the establishment of a lottery. Tennessee's Bob Corker was the only freshman Republican elected to the United States Senate in the 2006 midterm elections. The state constitution was amended to reject same-sex marriage. In January 2007, Ron Ramsey became the first Republican elected as Speaker of the State Senate since Reconstruction, as a result of the realignment of the Democratic and Republican parties in the South since the late 20th century, with Republicans now elected by conservative voters, who previously had supported Democrats.

In 2010, during the 2010 midterm elections, Bill Haslam was elected to succeed Bredesen, who was term-limited, to become the 49th Governor of Tennessee in January 2011. In April and May 2010, flooding in Middle Tennessee devastated Nashville and other parts of Middle Tennessee. In 2011, parts of East Tennessee, including Hamilton and Bradley counties, were devastated by the April 2011 tornado outbreak.

In 2018, Republican businessman Bill Lee was elected to succeed term-limited Haslam, and he became the 50th Governor of Tennessee.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 35,691 | — | |

| 1800 | 105,602 | 195.9% | |

| 1810 | 261,727 | 147.8% | |

| 1820 | 422,823 | 61.6% | |

| 1830 | 681,904 | 61.3% | |

| 1840 | 829,210 | 21.6% | |

| 1850 | 1,002,717 | 20.9% | |

| 1860 | 1,109,801 | 10.7% | |

| 1870 | 1,258,520 | 13.4% | |

| 1880 | 1,542,359 | 22.6% | |

| 1890 | 1,767,518 | 14.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,020,616 | 14.3% | |

| 1910 | 2,184,789 | 8.1% | |

| 1920 | 2,337,885 | 7.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,616,556 | 11.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,915,841 | 11.4% | |

| 1950 | 3,291,718 | 12.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,567,089 | 8.4% | |

| 1970 | 3,923,687 | 10.0% | |

| 1980 | 4,591,120 | 17.0% | |

| 1990 | 4,877,185 | 6.2% | |

| 2000 | 5,689,283 | 16.7% | |

| 2010 | 6,346,105 | 11.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 6,829,174 | 7.6% | |

| Source: 1910–2010[53] 2019 estimate[4] | |||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Tennessee was 6,829,174 on July 1, 2019, an increase of 483,069 people since the 2010 United States Census, or 7.61%.[4] This includes a natural increase since the last census of 124,385 (584,236 births minus 459,851 deaths), and an increase from net migration of 244,537 people into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 66,412, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 178,125.[54]

Twenty percent of Tennesseans were born outside the South in 2008, compared to a figure of 13.5% in 1990.[55] In recent years, Tennessee has received an influx of people relocating from California, Florida, New York, New Jersey and the New England States for the low cost of living, and the booming healthcare and automobile industries. Metropolitan Nashville is one of the fastest-growing areas in the country due in part to these factors.[56]

The center of population of Tennessee is located in Rutherford County, in the city of Murfreesboro.[57]

Ethnicity

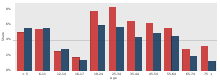

| Racial composition | 1970[58] | 1990[58] | 2000[59] | 2010[59] | 2018 est.[60] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 83.9% | 83.0% | 80.2% | 77.6% | 77.7% |

| Black | 15.8% | 16.0% | 16.4% | 16.7% | 16.8% |

| Asian | 0.1% | 0.7% | 1.0% | 1.4% | 1.7% |

| Native | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | - | – | – | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Other race | - | 0.2% | 1.0% | 2.2% | 1.4% |

| Two or more races | - | – | 1.1% | 1.7% | 2.1% |

In 2010, 4.6% of the total population was of Hispanic or Latino origin (they may be of any race), up from 2.2% in 2000. Between 2000 and 2010, the Hispanic population in Tennessee grew by 134.2%, the third highest of any state.[61] That same year Non-Hispanic whites were 75.6% of the population, compared to 63.7% of the population nationwide.[62]

In 2010, approximately 4.4% of Tennessee's population was foreign-born, an increase of about 118.5% since 2000. Of the foreign-born population, approximately 31.0% were naturalized citizens and 69.0% non-citizens. The foreign-born population was approximately 49.9% from Latin America, 27.1% from Asia, 11.9% from Europe, 7.7% from Africa, 2.7% from Northern America, and 0.6% from Oceania.[63]

In 2010, the five most common self-reported ethnic groups in the state were: American (26.5%), English (8.2%), Irish (6.6%), German (5.5%), and Scotch-Irish (2.7%).[64] Most Tennesseans who self-identify as having American ancestry are of English and Scotch-Irish ancestry. An estimated 21–24% of Tennesseans are of predominantly English ancestry.[65][66] In the 1980 census 1,435,147 Tennesseans claimed "English" or "mostly English" ancestry out of a state population of 3,221,354 making them 45% of the state at the time.[67]

According to the 2010 census, 6.4% of Tennessee's population were reported as under age 5, 23.6% under 18, and 13.4% were 65 or older.[68]

On June 19, 2010, the Tennessee Commission of Indian Affairs granted state recognition to six Native American tribes, which was later repealed by the state's Attorney General because the action by the commission was illegal. The tribes were as follows:

- The Cherokee Wolf Clan in western Tennessee, with members in Carroll County, Benton, Decatur, Henderson, Henry, Weakley, Gibson and Madison counties.

- The Chikamaka Band, based historically on the South Cumberland Plateau, said to have members in Franklin, Grundy, Marion, Sequatchie, Warren and Coffee counties.

- Central Band of Cherokee, also known as the Cherokee of Lawrence County.

- United Eastern Lenape Nation of Winfield.

- The Tanasi Council, said to have members in Shelby, Dyer, Gibson, Humphreys and Perry counties; and

- Remnant Yuchi Nation, with members in Sullivan, Carter, Greene, Hawkins, Unicoi, Johnson and Washington counties.[69]

Birth data

As of 2011, 36.3% of Tennessee's population younger than age 1 were minorities.[70]

Note: Births in table do not add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[71] | 2014[72] | 2015[73] | 2016[74] | 2017[75] | 2018[76] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 59,804 (74.7%) | 61,391 (75.2%) | 61,814 (75.7%) | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 54,377 (68.0%) | 55,499 (68.0%) | 55,420 (67.8%) | 53,866 (66.7%) | 53,721 (66.3%) | 53,256 (66.0%) |

| Black | 17,860 (22.3%) | 17,791 (21.8%) | 17,507 (21.4%) | 15,889 (19.7%) | 16,050 (19.8%) | 15,921 (19.7%) |

| Asian | 2,097 (2.6%) | 2,180 (2.7%) | 2,153 (2.6%) | 1,875 (2.3%) | 1,905 (2.4%) | 1,877 (2.3%) |

| American Indian | 231 (0.3%) | 240 (0.3%) | 211 (0.2%) | 77 (0.1%) | 150 (0.2%) | 148 (0.2%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 6,854 (8.6%) | 6,986 (8.6%) | 7,264 (8.9%) | 7,631 (9.4%) | 7,684 (9.5%) | 7,824 (9.7%) |

| Total Tennessee | 79,992 (100%) | 81,602 (100%) | 81,685 (100%) | 80,807 (100%) | 81,016 (100%) | 80,751 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

Religion

The religious affiliations of the people of Tennessee as of 2014:[77]

- Christian 81%

- Protestant 73%

- Evangelical Protestant 52%

- Mainline Protestant 13%

- Historically Black Protestant 8%

- Roman Catholic 6%

- Mormon 1%

- Orthodox Christian <1%

- Other Christian (includes unspecified "Christian" and "Protestant") <1%

- Protestant 73%

- Islam 1%

- Jewish 1%

- Other religions 3%

- Non-religious 14%

The largest denominations by number of adherents in 2010 were the Southern Baptist Convention with 1,483,356; the United Methodist Church with 375,693; the Roman Catholic Church with 222,343; and the Churches of Christ with 214,118.[78]

As of January 1, 2009, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) reported 43,179 members, 10 stakes, 92 Congregations (68 wards and 24 branches), two missions, and two temples in Tennessee.[79]

Tennessee is home to several Protestant denominations, such as the National Baptist Convention (headquartered in Nashville); the Church of God in Christ and the Cumberland Presbyterian Church (both headquartered in Memphis); the Church of God and The Church of God of Prophecy (both headquartered in Cleveland). The Free Will Baptist denomination is headquartered in Antioch; its main Bible college is in Nashville. The Southern Baptist Convention maintains its general headquarters in Nashville. Publishing houses of several denominations are located in Nashville.

Economy

- Total employment: 2,592,600

- Total employee establishments: 135,352[80]

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, in 2011 Tennessee's real gross state product was $233.997 billion. In 2003, the per capita personal income was $28,641, 36th in the nation, and 91% of the national per capita personal income of $31,472. In 2004, the median household income was $38,550, 41st in the nation, and 87% of the national median of $44,472.

For 2012, the state held an asset surplus of $533 million, one of only eight states in the nation to report a surplus.[81]

Major outputs for the state include textiles, cotton, cattle, and electrical power. Tennessee has more than 82,000 farms, roughly 59 percent of which accommodate beef cattle.[82] Although cotton was an early crop in Tennessee, large-scale cultivation of the fiber did not begin until the 1820s with the opening of the land between the Tennessee and Mississippi Rivers. The upper wedge of the Mississippi Delta extends into southwestern Tennessee, and it was in this fertile section that cotton took hold. Soybeans are also heavily planted in West Tennessee, focusing on the northwest corner of the state.[83]

Large corporations with headquarters in Tennessee include FedEx, AutoZone and International Paper, all based in Memphis; Pilot Corporation and Regal Entertainment Group, based in Knoxville; Eastman Chemical Company, based in Kingsport; Hospital Corporation of America and Caterpillar Financial, based in Nashville; and Unum, based in Chattanooga.

Tennessee is also a major hub for the automotive industry.[84] Three automobile manufacturers have factories in Tennessee: Nissan in Smyrna, General Motors in Spring Hill, and Volkswagen in Chattanooga.[85] Nissan moved its North American corporate headquarters from California to Franklin, Tennessee in 2005,[86] and Mitsubishi Motors did the same in 2019.[84]

Other major manufacturers include a $2 billion polysilicon production facility owned by Wacker Chemie in Bradley County and a $1.2 billion polysilicon production facility owned by Hemlock Semiconductor in Clarksville.

Tennessee is a right to work state, as are most of its Southern neighbors. Unionization has historically been low and continues to decline as in most of the U.S. generally. As of August 2019, the state has an unemployment rate of 3.5%, which is ranked 28th in the country.[87] As of 2015, 16.7% of the population of Tennessee lives below the poverty line, which is higher than the national average of 14.7%.[88]

Taxation

Tennessee has a reputation as low-tax state and is usually ranked as one of the five states with the lowest tax burden on residents.[89] It is one of nine states that do not have a general income tax; the sales tax is the primary means of funding the government.[90] The Hall income tax is a tax imposed on most dividends and interest. The tax rate was 6% from 1937 to 2016, but is in the process of being completely phased out by January 1, 2021.[91] The first $1,250 of individual income and $2,500 of joint income is exempt from this tax.[92]

The state's sales and use tax rate for most items is 7%, the second-highest in the nation, along with Mississippi, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Indiana. Food is taxed at a lower rate of 4%, but candy, dietary supplements and prepared food are taxed at 7%.[93] Local sales taxes are collected in most jurisdictions at rates varying from 1.5% to 2.75%, bringing the total sales tax to between 8.5% and 9.75%, with an average rate of about 9.5%, the nation's highest average sales tax.[94] Intangible property tax is assessed on the shares of stock of stockholders of any loan, investment, insurance, or for-profit cemetery companies. The assessment ratio is 40% of the value times the jurisdiction's tax rate.[95] Since January 1, 2016, Tennessee has had no inheritance tax.[96]

While sales tax remains the main source of state government funding, property taxes are the primary source of revenue for local governments.[95]

Tourism

Tourism contributes billions of dollars every year to the state's economy, and Tennessee is ranked among the Top 10 destinations in the nation.[97] In 2014 a record 100 million people visited the state resulting in $17.7 billion in tourism related spending within the state, an increase of 6.3% over 2013; tax revenue from tourism equaled $1.5 billion. Each county in Tennessee saw at least $1 million from tourism while 19 counties received at least $100 million (Davidson, Shelby, and Sevier counties were the top three). Tourism-generated jobs for the state reached 152,900, a 2.8% increase.[97] International travelers to Tennessee accounted for $533 million in spending.[98]

In 2013 tourism within the state from local citizens accounted for 39.9% of tourists, the second highest originating location for tourists to Tennessee is the state of Georgia, accounting for 8.4% of tourists.[99]:17 Forty-four percent of stays in the state were "day trips", 25% stayed one night, 15% stayed two nights, and 11% stayed four or more nights. The average stay was 2.16 nights, compared to 2.03 nights for the U.S. as a whole.[99]:40 The average person spent $118 per day: 29% on transportation, 24% on food, 17% on accommodation, and 28% on shopping and entertainment.[99]:44

Tennessee is home to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the most visited national park in the United States. The park anchors a large tourism industry based primarily in nearby Gatlinburg and Pigeon Forge, which consists of such attractions as Dollywood, the most visited ticketed attraction in Tennessee, Ober Gatlinburg, and Ripley's Aquarium of the Smokies.[100] Major attractions in Memphis include Graceland, the home of Elvis Presley, Beale Street, the National Civil Rights Museum, the Memphis Zoo, and the Stax Museum of American Soul Music.[101] Nashville contains many attractions related to its musical heritage, including Lower Broadway, the Country Music Hall of Fame, the Ryman Auditorium, Grand Ole Opry, and the Gaylord Opryland Resort. Other major attractions in Nashville include the Tennessee State Museum, Parthenon, and the Belle Meade Plantation.[102] Major attractions in Chattanooga include Lookout Mountain, the Chattanooga Choo-Choo Hotel, Ruby Falls, and the Tennessee Aquarium, the largest freshwater aquarium in the United States.[100] Other major attractions include the American Museum of Science and Energy in Oak Ridge, the Bristol Motor Speedway in Bristol, Jack Daniel's Distillery in Lynchburg, and the Hiwassee and Ocoee rivers in Polk County.[100]

Four Civil War battlefields in Tennessee are preserved by the National Park Service: Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, Stones River National Battlefield, Shiloh National Military Park, and Fort Donelson National Battlefield.[103] Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area is within the Cumberland Mountains in northeastern Tennessee. Other major attractions preserved by the National Park Service include Cumberland Gap National Historical Park and Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail.[104]

Energy and mineral production

Tennessee's electric utilities are regulated monopolies, as in many other states.[105][106] As of 2019, the Tennessee Valley Authority owned over 90% of generating capacity.[107] Nuclear power is the largest source of electricity generation in Tennessee, producing about 43.7% of its power in 2019. The same year, 22.9% of the power was produced by coal, 20.3% from natural gas, 12.1% from hydroelectric power, and 1.6% from other renewables. About 56% of the electricity generated in Tennessee produces no greenhouse gas emissions.[108] Tennessee is a net consumer of electricity, receiving power from other TVA facilities in neighboring states such as the Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant in northern Alabama.[109]

Tennessee is home to the two newest civilian nuclear power reactors in the United States, at Watts Bar Nuclear Plant in Rhea County. Unit 1 began operation in 1996 and Unit 2 began operation in 2016, making it the first and only new nuclear power reactor to begin operation in the United States in the 21st century.[110] Tennessee was also an early leader in hydroelectric power, first with the now defunct Chattanooga and Tennessee Electric Power Company; later, the United States Army Corps of Engineers and the TVA constructed several hydroelectric dams on Tennessee rivers.[111] Today, Tennessee is the third-largest hydroelectric power-producing state east of the Rocky Mountains.[112]

Tennessee has very little petroleum and natural gas reserves, but is home to one oil refinery, in Memphis.[112] Bituminous coal is mined in small quantities in the Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains.[113] There are sizable reserves of lignite coal in West Tennessee that remain untapped.[113] Coal production in Tennessee peaked in 1972, and today less than 0.1% of coal production in the United States comes from Tennessee mines.[112]

Tennessee is the leading producer of ball clay in the United States.[113] Other major mineral products produced in Tennessee include sand, gravel, crushed stone, Portland cement, marble, sandstone, common clay, lime, and zinc.[113][114] The Copper Basin, in Tennessee's southeastern corner in Polk County, was one of the most productive copper mining districts in the United States between the 1840s and 1980s.[115] Mines in the basin supplied about 90% of the copper used by the Confederacy during the Civil War,[116] and also marketed chemical byproducts of the mining, including sulfuric acid.[117] Mining activities in the basin resulted in a major environmental disaster, which left the landscape in the basin barren for more than a century.[118] Iron ore was another major mineral mined in Tennessee until the early 20th century.[119] Tennessee was also a top producer of phosphate until the early 1990s.[120]

Culture

Music

Tennessee has played a critical role in the development of many forms of American popular music, including rock and roll, blues, country, and rockabilly. Beale Street in Memphis is considered by many to be the birthplace of the blues, with musicians such as W. C. Handy performing in its clubs as early as 1909.[121] Memphis is also home to Sun Records, where musicians such as Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, and Charlie Rich began their recording careers, and where rock and roll took shape in the 1950s.[122] The 1927 Victor recording sessions in Bristol generally mark the beginning of the country music genre and the rise of the Grand Ole Opry in the 1930s helped make Nashville the center of the country music recording industry.[123][124] Three brick-and-mortar museums recognize Tennessee's role in nurturing various forms of popular music: the Memphis Rock N' Soul Museum, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, and the International Rock-A-Billy Museum in Jackson. Moreover, the Rockabilly Hall of Fame, an online site recognizing the development of rockabilly in which Tennessee played a crucial role, is based in Nashville.

Literature

Notable writers with ties to Tennessee include Cormac McCarthy, Peter Taylor, James Agee, Francis Hodgson Burnett, Thomas S. Stribling, Ida B. Wells, Nikki Giovanni, Shelby Foote, Ann Patchett, Ishmael Reed, and Randall Jarrell.

Sports

Tennessee is home to four major professional sports franchises: the Tennessee Titans have played in the National Football League since 1997, the Memphis Grizzlies have played in the National Basketball Association since 2001, the Nashville Predators have played in the National Hockey League since 1998, and Nashville SC has played in Major League Soccer since 2020.

The state is also home to 13 teams playing in minor leagues. Nine Minor League Baseball teams call the state their home. The Memphis Redbirds and Nashville Sounds, each of the Pacific Coast League, compete at the Triple-A level, the highest before Major League Baseball. The Chattanooga Lookouts, Jackson Generals, and Tennessee Smokies play in the Double-A Southern League. The Elizabethton Twins, Greeneville Reds, Johnson City Cardinals, and Kingsport Mets are Rookie League teams of the Appalachian League.

The Knoxville Ice Bears are a minor league ice hockey team of the Southern Professional Hockey League. Memphis 901 FC, a soccer team, joined the USL Championship in 2019.[125] Chattanooga Red Wolves SC became an inaugural member of the third-level USL League One in 2019. Chattanooga FC began play in the National Independent Soccer Association in 2020.

In Knoxville, the Tennessee Volunteers college team has played in the Southeastern Conference (SEC) of the National Collegiate Athletic Association since the conference was formed in 1932. The football team has won 13 SEC championships and 28 bowls, including four Sugar Bowls, three Cotton Bowls, an Orange Bowl and a Fiesta Bowl. Meanwhile, the men's basketball team has won four SEC championships and reached the NCAA Elite Eight in 2010. In addition, the women's basketball team has won a host of SEC regular-season and tournament titles along with eight national titles.

In Nashville, the Vanderbilt Commodores are also charter members of the SEC. The Tennessee–Vanderbilt football rivalry began in 1892, having since played more than a hundred times. In June 2014, the Vanderbilt Commodores baseball team won its first men's national championship by winning the 2014 College World Series.

The state is home to 10 other NCAA Division I programs. Two of these participate in the top level of college football, the Football Bowl Subdivision. The Memphis Tigers are members of the American Athletic Conference, and the Middle Tennessee Blue Raiders from Murfreesboro play in Conference USA. In addition to the Commodores, Nashville is also home to the Belmont Bruins and Tennessee State Tigers, both members of the Ohio Valley Conference (OVC), and the Lipscomb Bisons, members of the Atlantic Sun Conference. Tennessee State plays football in Division I's second level, the Football Championship Subdivision (FCS), while Belmont and Lipscomb do not have football teams. Belmont and Lipscomb have an intense rivalry in men's and women's basketball known as the Battle of the Boulevard, with both schools' men's and women's teams playing two games each season against each other (a rare feature among non-conference rivalries). The OVC also includes the Austin Peay Governors from Clarksville, the UT Martin Skyhawks from Martin, and the Tennessee Tech Golden Eagles from Cookeville. These three schools, along with fellow OVC member Tennessee State, play each season in football for the Sgt. York Trophy. The Chattanooga Mocs and Johnson City's East Tennessee State Buccaneers are full members, including football, of the Southern Conference.

Tennessee is also home to Bristol Motor Speedway which features NASCAR Cup Series racing two weekends a year, routinely selling out more than 160,000 seats on each date; it also was the home of the Nashville Superspeedway, which held Nationwide and IndyCar races until it was shut down in 2012. Tennessee's only graded stakes horse race, the Iroquois Steeplechase, is also held in Nashville each May.

The FedEx St. Jude Classic is a PGA Tour golf tournament held at Memphis since 1958. The U.S. National Indoor Tennis Championships has been held at Memphis since 1976 (men's) and 2002 (women's).

Sports teams

Transportation

Interstate highways

Interstate 40 crosses the state in an east–west orientation. Its branch interstate highways include I-240 in Memphis; I-440 in Nashville; I-840 in Nashville; I-140 from Knoxville to Alcoa; and I-640 in Knoxville. I-26, although technically an east–west interstate, runs from the North Carolina border below Johnson City to its terminus at Kingsport. I-24 is an east–west interstate that runs from Chattanooga to Clarksville. In a north–south orientation are highways I-55, I-65, I-75, and I-81. Interstate 65 crosses the state through Nashville, while Interstate 75 serves Chattanooga and Knoxville and Interstate 55 serves Memphis. Interstate 81 enters the state at Bristol and terminates at its junction with I-40 near Dandridge. I-155 is a branch highway from I-55. The only spur highway of I-75 in Tennessee is I-275, which is in Knoxville.[126] An extension of I-69 is proposed to travel through the western part of the state, from South Fulton to Memphis.[127] A branch interstate, I-269 also exists from Millington to Collierville.[126]

Airports

Major airports within the state include Memphis International Airport (MEM), Nashville International Airport (BNA), McGhee Tyson Airport (TYS) outside of Knoxville in Blount County, Chattanooga Metropolitan Airport (CHA), Tri-Cities Regional Airport (TRI), and McKellar-Sipes Regional Airport (MKL), in Jackson. Because Memphis International Airport is the major hub for FedEx Corporation, it is the world's largest air cargo operation.

Railroads

For passenger rail service, Memphis and Newbern, are served by the Amtrak City of New Orleans line on its run between Chicago, Illinois, and New Orleans, Louisiana. Nashville is served by the Music City Star commuter rail service.

Cargo services in Tennessee are primarily served by CSX Transportation, which has a hump yard in Nashville called Radnor Yard. Norfolk Southern Railway operates lines in East Tennessee, through cities including Knoxville and Chattanooga, and operates a classification yard near Knoxville, the John Sevier Yard. BNSF operates a major intermodal facility in Memphis.

Governance

Similar to the United States Federal Government, Tennessee's government has three parts. The Executive Branch is led by Tennessee's governor, who holds office for a four-year term and may serve a maximum of two consecutive terms. The governor is the only official who is elected statewide. Unlike most states, the state does not elect the lieutenant governor directly; the Tennessee Senate elects its Speaker, who serves as lieutenant governor. The governor is supported by 22 cabinet-level departments, most headed by a commissioner who serves at the pleasure of the governor:

- Department of Agriculture

- Department of Children's Services

- Department of Commerce and Insurance

- Department of Correction

- Department of Economic & Community Development

- Department of Education

- Department of Environment and Conservation

- Department of Finance and Administration

- Department of Financial Institutions

- Department of General Services

- Department of Health

- Department of Human Resources

- Department of Human Services

- Department of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

- Department of Labor and Workforce Development

- Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services

- Department of Military

- Department of Revenue

- Department of Safety and Homeland Security

- Department of Tourist Development

- Department of Transportation

- Department of Veterans Services

The Executive Branch also includes several agencies, boards and commissions, some of which are under the auspices of one of the cabinet-level departments.[128]

The bicameral Legislative Branch, known as the Tennessee General Assembly, consists of the 33-member Senate and the 99-member House of Representatives. Senators serve four-year terms, and House members serve two-year terms. Each chamber chooses its own speaker. The speaker of the state Senate also holds the title of lieutenant governor. Constitutional officials in the legislative branch are elected by a joint session of the legislature.

The highest court in Tennessee is the state Supreme Court. It has a chief justice and four associate justices. No more than two justices can be from the same Grand Division. The Supreme Court of Tennessee also appoints the Attorney General, a practice not found in any of the other 49 states. Both the Court of Appeals and the Court of Criminal Appeals have 12 judges.[129] A number of local, circuit, and federal courts provide judicial services.

Tennessee's current state constitution was adopted in 1870. The state had two earlier constitutions. The first was adopted in 1796, the year Tennessee joined the union, and the second was adopted in 1834. The 1870 Constitution outlaws martial law within its jurisdiction. This may be a result of the experience of Tennessee residents and other Southerners during the period of military control by Union (Northern) forces of the U.S. government after the American Civil War.

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 60.72% 1,522,925 | 34.72% 870,695 |

| 2012 | 59.42% 1,462,330 | 39.04% 960,709 |

| 2008 | 56.85% 1,479,178 | 41.79% 1,087,437 |

| 2004 | 56.80% 1,384,375 | 42.53% 1,036,477 |

| 2000 | 51.15% 1,061,949 | 47.28% 981,720 |

| 1996 | 45.59% 863,530 | 48.00% 909,146 |

| 1992 | 42.43% 841,300 | 47.08% 933,521 |

| 1988 | 57.89% 947,233 | 41.55% 679,794 |

| 1984 | 57.84% 990,212 | 41.57% 711,714 |

| 1980 | 48.70% 787,761 | 48.41% 783,051 |

| 1976 | 42.94% 633,969 | 55.94% 825,879 |

| 1972 | 67.70% 813,147 | 29.75% 357,293 |

| 1968 | 37.85% 472,592 | 28.13% 351,233 |

| 1964 | 44.49% 508,965 | 55.50% 634,947 |

| 1960 | 52.92% 556,577 | 45.77% 481,453 |

Tennessee politics, like that of most U.S. states, are dominated by the Republican and the Democratic parties. Historian Dewey W. Grantham traces divisions in the state to the period of the American Civil War; for decades afterward, the eastern third of the state was heavily Republican and the western two thirds mostly voted Democratic.[130] This division was related to the state's pattern of farming, plantations and slaveholding. The eastern section was made up of yeoman farmers, but Middle and West Tennessee farmers cultivated crops such as tobacco and cotton which were dependent on the use of slave labor. These areas became defined as Democratic after the war.

During Reconstruction, freedmen and former free people of color were granted the right to vote; most joined the Republican Party. Numerous African Americans were elected to local offices, and some to state office. Following Reconstruction, Tennessee continued to have competitive party politics, but in the 1880s, the white-dominated state government passed four laws, the last of which imposed a poll tax requirement for voter registration. These served to disenfranchise most African Americans, and their power in state and local politics was markedly reduced. In 1900 African Americans comprised 23.8 percent of the state's population, concentrated in Middle and West Tennessee.[50] In the early 1900s, the state legislature approved a form of commission government for cities based on at-large voting for a few positions on a Board of Commission; several cities adopted this as another means to limit African-American political participation. In 1913 the state legislature enacted a bill enabling cities to adopt this structure without legislative approval.[131]

After disenfranchisement of blacks, the Republican Party in Tennessee became a primarily white sectional party supported only in the eastern part of the state. In the 20th century, except for two nationwide Republican landslides of the 1920s (in 1920, when Tennessee narrowly supported Warren G. Harding over Ohio Governor James Cox, and in 1928, when it more decisively voted for Herbert Hoover over New York Governor Al Smith), the state was part of the Democratic Solid South until the 1950s. In that postwar decade, it twice voted for Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, former Allied Commander of the Armed Forces during World War II. Since then, more of the state's voters have shifted to supporting Republicans, and Democratic presidential candidates have carried Tennessee only four times.

By 1960 African Americans comprised 16.45% of the state's population. It was not until after the mid-1960s and passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that they were able to vote in full again, but new devices, such as at-large commission city governments, had been adopted in several jurisdictions to limit their political participation. Former Gov. Winfield Dunn and former U.S. Sen. Bill Brock wins in 1970 helped make the Republican Party competitive among whites for the statewide victory. Tennessee has selected governors from different parties since 1970.

In the early 21st century, Republican voters control most of the state, especially in the more rural and suburban areas outside of the cities; Democratic strength is mostly confined to the urban cores of the four major cities, and is particularly strong in the cities of Nashville and Memphis. The latter area includes a large African-American population.[132] Historically, Republicans had their greatest strength in East Tennessee before the 1960s. Tennessee's 1st and 2nd congressional districts, based in the Tri-Cities and Knoxville, respectively, are among the few historically Republican districts in the South. Those districts' residents supported the Union over the Confederacy during the Civil War; they identified with the GOP after the war and have stayed with that party ever since. The first has been in Republican hands continuously since 1881, and Republicans (or their antecedents) have held it for all but four years since 1859. The second has been held continuously by Republicans or their antecedents since 1859.

In the 2000 presidential election, Vice President Al Gore, a Democratic U.S. Senator from Tennessee, failed to carry his home state, an unusual occurrence but indicative of strengthening Republican support. Republican George W. Bush received increased support in 2004, with his margin of victory in the state increasing from 4% in 2000 to 14% in 2004.[133] Democratic presidential nominees from Southern states, such as Lyndon B. Johnson, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton, usually fare better than their Northern counterparts do in Tennessee, especially among split-ticket voters outside the metropolitan areas.

Tennessee sends nine members to the U.S. House of Representatives, of whom there are seven Republicans and two Democrats. Lieutenant Governor Ron Ramsey is the first Republican speaker of the state Senate in 140 years. In the 2008 elections, the Republican party gained control of both houses of the Tennessee state legislature for the first time since Reconstruction. In 2008, some 30% of the state's electorate identified as independents.[134]

The Baker v. Carr (1962) decision of the U.S. Supreme Court established the principle of "one man, one vote", requiring state legislatures to redistrict to bring Congressional apportionment in line with decennial censuses. It also required both houses of state legislatures to be based on population for representation and not geographic districts such as counties. This case arose out of a lawsuit challenging the longstanding rural bias of apportionment of seats in the Tennessee legislature.[135][136][137] After decades in which urban populations had been underrepresented in many state legislatures, this significant ruling led to an increased (and proportional) prominence in state politics by urban and, eventually, suburban, legislators and statewide officeholders in relation to their population within the state. The ruling also applied to numerous other states long controlled by rural minorities, such as Alabama, Vermont, and Montana.

Law enforcement

State agencies

The state of Tennessee maintains four dedicated law enforcement entities: the Tennessee Highway Patrol, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA), the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation (TBI), and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC).

The Highway Patrol is the primary law enforcement entity that concentrates on highway safety regulations and general non-wildlife state law enforcement and is under the jurisdiction of the Tennessee Department of Safety. The TWRA is an independent agency tasked with enforcing all wildlife, boating, and fisheries regulations outside of state parks. The TBI maintains state-of-the-art investigative facilities and is the primary state-level criminal investigative department. Tennessee State Park Rangers are responsible for all activities and law enforcement inside the Tennessee State Parks system.

Local

Local law enforcement is divided between County Sheriff's Offices and Municipal Police Departments. Tennessee's Constitution requires that each County have an elected Sheriff. In 94 of the 95 counties the Sheriff is the chief law enforcement officer in the county and has jurisdiction over the county as a whole. Each Sheriff's Office is responsible for warrant service, court security, jail operations and primary law enforcement in the unincorporated areas of a county as well as providing support to the municipal police departments. Incorporated municipalities are required to maintain a police department to provide police services within their corporate limits.

The three counties in Tennessee to adopt metropolitan governments have taken different approaches to resolving the conflict that a Metro government presents to the requirement to have an elected Sheriff.

- Nashville/Davidson County converted law enforcement duties entirely to the Metro Nashville Police Chief. In this instance the Sheriff is no longer the chief law enforcement officer for Davidson County. The Davidson County Sheriff's duties focus on warrant service and jail operations. The Metropolitan Police Chief is the chief law enforcement officer and the Metropolitan Police Department provides primary law enforcement for the entire county.

- Lynchburg/Moore County took a much simpler approach and abolished the Lynchburg Police Department when it consolidated and placed all law enforcement responsibility under the sheriff's office.

- Hartsville/Trousdale County, although the smallest county in Tennessee, adopted a system similar to Nashville's, which retains the sheriff's office but also has a metropolitan police department.

Firearms

Gun laws in Tennessee regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition. Concealed carry and open-carry of a handgun is permitted with a Tennessee handgun carry permit or an equivalent permit from a reciprocating state. As of July 1, 2014, a permit is no longer required to possess a loaded handgun in a motor vehicle.[138]

Capital punishment

Capital punishment has existed in Tennessee at various times since statehood. Before 1913, the method of execution was hanging. From 1913 to 1915, there was a hiatus on executions but they were reinstated in 1916 when electrocution became the new method. From 1972 to 1978, after the Supreme Court ruled (Furman v. Georgia) capital punishment unconstitutional, there were no further executions. Capital punishment was restarted in 1978, although those prisoners awaiting execution between 1960 and 1978 had their sentences mostly commuted to life in prison.[139] From 1916 to 1960 the state executed 125 inmates.[140] For a variety of reasons there were no further executions until 2000. Since 2000, Tennessee has executed seven prisoners. Tennessee has 59 prisoners on death row (as of October 2018).[141]

Lethal injection was approved by the legislature in 1998, though those who were sentenced to death before January 1, 1999, may request electrocution.[139] In May 2014, the Tennessee General Assembly passed a law allowing the use of the electric chair for death row executions when lethal injection drugs are not available.[142][143]

Tribal

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians is the only federally recognized Native American Indian tribe in the state. It owns 79 acres (32 ha) in Henning, which was placed into federal trust by the tribe in 2012. This is governed directly by the tribe.[144][145]

Media

Education

Tennessee has a rich variety of public, private, charter, and specialized education facilities ranging from pre-school through university.

Colleges and universities

Public higher education is under the oversight of the Tennessee Higher Education Commission which provides guidance to two public university systems—the University of Tennessee system and the Tennessee Board of Regents. In addition a number of private colleges and universities are located throughout the state.

- American Baptist College

- Aquinas College

- The Art Institutes

- Austin Peay State University

- Baptist College of Health Sciences

- Belmont University

- Bethel College

- Bryan College

- Carson–Newman University

- Chattanooga State Community College

- Christian Brothers University

- Cleveland State Community College

- Columbia State Community College

- Crown College

- Cumberland University

- Dyersburg State Community College

- East Tennessee State University

- Emmanuel Christian Seminary

- Fisk University

- Freed–Hardeman University

- Jackson State Community College

- Johnson University

- King University

- Knoxville College

- Lane College

- Lee University

- LeMoyne–Owen College

- Lincoln Memorial University

- Lipscomb University

- Martin Methodist College

- Maryville College

- Meharry Medical College

- Memphis College of Art

- Memphis Theological Seminary

- Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary

- Middle Tennessee State University

- Milligan College