Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River.[5] It is approximately 652 miles (1,049 km) long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names, as many of the Cherokee had their territory along its banks, especially in eastern Tennessee and northern Alabama.[1] Its current name is derived from the Cherokee village Tanasi.[6]

| Tennessee River | |

|---|---|

The Tennessee River in downtown Chattanooga | |

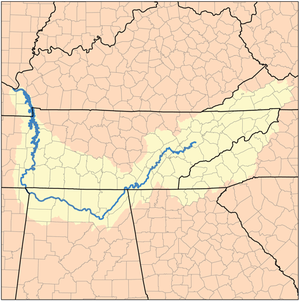

Map of the Tennessee River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Kentucky |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Confluence of French Broad and Holston rivers at Knoxville |

| • coordinates | 35°57′33″N 83°51′01″W[1] |

| • elevation | 813 ft (248 m)[2] |

| Mouth | Ohio River at Livingston / McCracken counties, near Paducah, Kentucky |

• coordinates | 37°04′02″N 88°33′53″W[1] |

• elevation | 302 ft (92 m)[3] |

| Length | 652 mi (1,049 km)[1] |

| Basin size | 40,876 sq mi (105,870 km2)[4] |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 70,575 cu ft/s (1,998.5 m3/s)[4] |

| • maximum | 500,000 cu ft/s (14,000 m3/s) |

Course

The Tennessee River is formed at the confluence of the Holston and French Broad rivers in present-day Knoxville, Tennessee. From Knoxville, it flows southwest through East Tennessee into Chattanooga before crossing into Alabama. It travels through the Huntsville and Decatur area before reaching the Muscle Shoals area, and eventually forms a small part of the state's border with Mississippi, before returning to Tennessee. Its route northerly through Tennessee defines the boundary between two of Tennessee's Grand Divisions: Middle and West Tennessee.

The Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project providing navigation on the Tombigbee River and a link to the Port of Mobile, enters the Tennessee River near the Tennessee-Alabama-Mississippi boundary. This waterway reduces the navigation distance from Tennessee, north Alabama, and northern Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico by hundreds of miles. The final part of the Tennessee's run is north through western Kentucky, where it separates the Jackson Purchase from the rest of the state. It flows into the Ohio River at Paducah, Kentucky.

Dams

The river has been dammed numerous times, primarily during the 20th century since the 1930s by Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) projects. The construction of TVA's Kentucky Dam on the Tennessee River and the Corps of Engineers' Barkley Dam on the Cumberland River led to the development of associated lakes, and the creation of what is called Land Between the Lakes. A navigation canal located at Grand Rivers, Kentucky, links Kentucky Lake and Lake Barkley. The canal allows for a shorter trip for river traffic going from the Tennessee to most of the Ohio River, and for traffic going down the Cumberland River toward the Mississippi.

Important cities and towns

- Bridgeport, Alabama

- Chattanooga, Tennessee

- Cherokee, Alabama

- Clifton, Tennessee

- Crump, Tennessee

- Decatur, Alabama

- Florence, Alabama

- Gilbertsville, Kentucky

- Grand Rivers, Kentucky

- Guntersville, Alabama

- Harrison, Tennessee

- Huntsville, Alabama

- Killen, Alabama

- Kingston, Tennessee

- Knoxville, Tennessee

- Langston, Alabama

- Lenoir City, Tennessee

- Loudon, Tennessee

- Muscle Shoals, Alabama

- New Johnsonville, Tennessee

- Paducah, Kentucky

- Savannah, Tennessee

- Scottsboro, Alabama

- Sheffield, Alabama

- Soddy-Daisy, Tennessee

- Signal Mountain, Tennessee

- South Pittsburg, Tennessee

- Triana, Alabama

- Waterloo, Alabama

History

Name

The river appears on French maps from the late 17th century with the names "Caquinampo" or "Kasqui." Maps from the early 18th century call it "Cussate," "Hogohegee," "Callamaco," and "Acanseapi." A 1755 British map showed the Tennessee River as the "River of the Cherakees."[7] By the late 18th century, it had come to be called "Tennessee," a name derived from the Cherokee village named Tanasi.[6][7]

Beginning

The Tennessee River begins at mile post 652, where the French Broad River meets the Holston River, but historically there were several different definitions of its starting point. In the late 18th century, the mouth of the Little Tennessee River (at Lenoir City) was considered to be the beginning of the Tennessee River. Through much of the 19th century, the Tennessee River was considered to start at the mouth of Clinch River (at Kingston). An 1889 declaration by the Tennessee General Assembly designated Kingsport (on the Holston River) as the start of the Tennessee, but the following year a federal law was enacted that finally fixed the start of the river at its current location.[7]

Water rights and border dispute between Georgia and Tennessee

At various points since the early 19th century, Georgia has disputed its northern border with Tennessee. In 1796, when Tennessee was admitted to the Union, the border was originally defined by United States Congress as located on the 35th parallel, thereby ensuring that at least a portion of the river would be located within Georgia. As a result of an erroneously conducted survey in 1818 (ratified by the Tennessee legislature, but not Georgia), however, the actual border line was set on the ground approximately one mile south, thus placing the disputed portion of the river entirely in Tennessee.[8][9]

Georgia made several unsuccessful attempts to correct what Georgia felt was an erroneous survey line "in the 1890s, 1905, 1915, 1922, 1941, 1947 and 1971 to 'resolve' the dispute", according to C. Crews Townsend, Joseph McCoin, Robert F. Parsley, Alison Martin and Zachary H. Greene, writing for the Tennessee Bar Journal, a publication of the Tennessee Bar Association, appearing on May 12, 2008.[10]

In 2008, as a result of a serious drought and resulting water shortage, the Georgia General Assembly passed a resolution directing the governor to pursue its claim in the United States Supreme Court.[11][12]

According to a story aired on WTVC-TV in Chattanooga on March 14, 2008, a local attorney familiar with case law on border disputes, says the U.S. Supreme Court generally will maintain the original borders between states and avoid stepping into border disputes, preferring the parties work out their differences.[13]

The Chattanooga Times Free Press reported on 25 March 2013 that Georgia senators approved House Resolution 4 stating that if Tennessee declines to settle with them, the dispute will be handed over to the attorney general, who will take Tennessee before the Supreme Court to settle the issue once and for all.[14] The Atlantic Wire, in commenting on Georgia's actions stated: The Great Georgia-Tennessee Border War of 2013 Is Upon Us Historians, take note: On this day, which is not a day in 1732, a boundary dispute between two Southern states took a turn for the wet. In a two-page resolution passed overwhelmingly by the state senate, Georgia declared that it, not its neighbor to the north, controls part of the Tennessee River at Nickajack. Georgia doesn't want Nickajack. It wants that water..[15]

Modern use

The Tennessee River is an important part of the Great Loop, the recreational circumnavigation of Eastern North America by water.

The Tennessee River has historically been a major highway for riverboats through the south and today they are still found along the river in abundance. Major ports include Guntersville, Chattanooga, Decatur, Yellow Creek, and Muscle Shoals. Navigation has contributed greatly to the economic and industrial development of the Tennessee Valley as a whole. The economies of cities like Decatur and Chattanooga would not be as dynamic as they are today, were it not for the Tennessee River. Many companies still rely on the river as a means of transportation for their materials. In Chattanooga, for example, steel is exported on boats, as it is much more efficient than moving it on land.[16] Locks along the Tennessee River waterway provide passage between reservoirs for more than 13,000 recreational craft each year. The Chickamauga Dam, located just upstream from Chattanooga, is currently planned to have a new lock built. However, the project has been delayed due to a lack of funding.[17] The river not only has many economic functions, such as the boat building industry and transportation, but it also provides water and natural resources to those who live near the river. Many of the major ports on the river are connected to a settlement that was started because of its proximity to the river.

Ecology

The Tennessee River and its tributaries host some 102 species of mussel.[18] Native Americans ate freshwater mussels. Potters of the Mississippian Culture used crushed mussel shell mixed into clay to make their pottery stronger.

A "pearl" button industry was established in the Tennessee Valley beginning in 1887, producing buttons from the abundant mussel shells. Button production ceased after World War II when plastics replaced mother-of-pearl as a button material.[19] Mussel populations have declined drastically due to dam construction, water pollution, and invasive species.[18]

Tennessee River tributaries

Tributaries and sub-tributaries are listed hierarchically in order from the mouth of the Tennessee River upstream.

- Horse Creek (Tennessee)

- Big Sandy River (Tennessee)

- White Oak Creek

- Duck River (Tennessee)

- Buffalo River (Tennessee)

- Piney River (Tennessee)

- Little Duck River

- Beech River (Tennessee)

- Shoal Creek

- Bear Creek (Alabama, Mississippi) [20]

- Buzzard Roost Creek (Alabama) [20]

- Colbert Creek (Alabama) [20]

- Cotaco Creek (Alabama)

- Malone Creek (Alabama) [20]

- Mulberry Creek (Alabama) [20]

- Cane Creek (Alabama) [20]

- Dry Creek (Alabama) [20]

- Little Bear Creek (Alabama) [20]

- Spring Creek (Alabama)

- Cypress Creek (Alabama)

- Shoal Creek (Alabama)

- First Creek (Alabama)

- Elk River (Tennessee, Alabama)

- Flint Creek (Alabama)

- Limestone Creek (Alabama, Tennessee)

- Beaverdam Creek (Alabama)

- Indian Creek (Alabama)

- Barren Fork Creek

- Flint River (Alabama, Tennessee)

- Paint Rock River (Alabama, Tennessee)

- Sequatchie River (Tennessee)

- Mountain Creek (Tennessee)

- Lookout Creek (Tennessee, Georgia)

- Chattanooga Creek (Tennessee, Georgia)

- Citico Creek (Tennessee)

- South Chickamauga Creek (Tennessee, Georgia)

- North Chickamauga Creek (Tennessee)

- Hiwassee River (Tennessee, North Carolina)

- Conasauga Creek (Tennessee)

- Ocoee River (Tennessee, Georgia)

- Nottely River (North Carolina, Georgia)

- Piney River (Tennessee)

- Clinch River (Tennessee, Virginia)

- Emory River (Tennessee)

- Little Emory River

- Obed River (Tennessee)

- Poplar Creek

- East Fork Poplar Creek

- Beaver Creek

- Powell River (Tennessee, Virginia)

- Emory River (Tennessee)

- Little Tennessee River (Tennessee, North Carolina)

- Tellico River (Tennessee)

- Tuckasegee River (North Carolina)

- Nantahala River (North Carolina)

- Cullasaja River (North Carolina)

- Little River (Tennessee)

- French Broad River

- Little Pigeon River (Tennessee)

- Nolichucky River (Tennessee, North Carolina)

- Pigeon River (Tennessee, North Carolina)

- Swannanoa River (North Carolina)

- Holston River (Tennessee)

- North Fork Holston River (Tennessee, Virginia)

- South Fork Holston River (Tennessee, Virginia)

- Watauga River (Tennessee, North Carolina)

- Doe River (Tennessee)

- Watauga River (Tennessee, North Carolina)

- Middle Fork Holston River (Virginia)

See also

- List of Alabama rivers

- List of crossings of the Tennessee River

- List of dams and reservoirs of the Tennessee River

- List of Kentucky rivers

- List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem)

- List of Mississippi rivers

- List of Tennessee rivers

- Stare decisis

- Tennessee River 600

- Tennessee River Valley

- Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway

Notes

- "Tennessee River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- U.S. Geological Survey. Shooks Gap quadrangle, Tennessee. 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. Washington D.C.: USGS, 1987.

- U.S. Geological Survey. Paducah East quadrangle, Kentucky. 1:24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. Washington D.C.: USGS, 1982.

- "Arthur Benke & Colbert Cushing, "Rivers of North America". Elsevier Academic Press, 2005 ISBN 0-12-088253-1

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2017-12-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bright, William (2004). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Ann Toplovich, Tennessee River System Archived 2012-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, December 25, 2009; updated January 1, 2010; accessed July 14, 2011

- "Georgians thirst to move Tennessee state line". February 8, 2008. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved 2008-05-13.

- "Desperate for water, Georgia revisits border dispute". February 8, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-13.

- "Crossing the Line | Tennessee Bar Association". Tba.org. Archived from the original on 2015-07-08. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Jones, Andrea (February 20, 2008). "Ga.'s quest to move Tenn. border advances". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- Dewan, Shaila (February 22, 2008). "Georgia Claims a Sliver of the Tennessee River". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2011. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- Group, Sinclair Broadcast. "CHATTANOOGA News, Weather, Sports, Breaking News – WTVC". Archived from the original on 2009-07-22. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- "Tennessee, Georgia at war over state line; battle could go to Supreme Court". March 25, 2013. Archived from the original on March 29, 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- "The Great Georgia-Tennessee Border War of 2013 Is Upon Us". March 25, 2013. Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- "Navigation on the Tennessee River". tva.com. TVA. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- "Chickamauga Lock Addition Project". lrn.usace.army.mil. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- Freshwater Mussels Archived 2016-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries website, accessed July 14, 2011

- Tennessee Freshwater Mussels Archived 2013-03-23 at the Wayback Machine, Frank H. McClung Museum website, accessed July 14, 2011

- Alabama Department of Transportation (1997). "County Highway Maps". University of Alabama. Archived from the original (Lizardtech Plugin) on 2009-01-30. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

Further reading

- Woodside, M.D. et al. (2004). Water quality in the lower Tennessee River Basin, Tennessee, Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Georgia, 1999–2001 [U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1233]. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Myers, Fred (2004). Tennessee River CruiseGuide, 5th Edition

- Hay, Jerry (2010). Tennessee River Guidebook, 1st Edition

- Rumsey, W.J. (2007). A Cruising Guide to the Tennessee River, Tenn-Tom Waterway, and Lower Tombigbee River

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tennessee River. |

- Tennessee Rivers

- Map of Tennessee River in Alabama

- Tennessee River Navigation Charts

- Chickamauga dam progress