Ice hockey

Ice hockey is a contact team sport played on ice, usually in a rink, in which two teams of skaters use their sticks to shoot a vulcanized rubber puck into their opponent's net to score goals. The sport is known to be fast-paced and physical, with teams usually fielding six players at a time: one goaltender, and five players who skate the span of the ice trying to control the puck and score goals against the opposing team.

.jpg) The Toronto Maple Leafs (white) defend their goal against the Washington Capitals (red) during the first round of the 2017 Stanley Cup playoffs. | |

| Highest governing body | International Ice Hockey Federation |

|---|---|

| First played | 19th century Canada (contested) |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full |

| Team members |

|

| Type | Team sport, stick sport, puck sport, winter sport |

| Equipment | Hockey pucks, sticks, skates, shin pads, shoulder pads, gloves, helmets (with visor or cage, depending on age of player and league), elbow pads, jock or jill, socks, shorts, neck guard (depends on league), mouthguard (depends on league) |

| Venue | Hockey rink or arena, and is sometimes played on a frozen lake or pond for recreation |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | |

Ice hockey is most popular in Canada, central and eastern Europe, the Nordic countries, Russia, and the United States. Ice hockey is the official national winter sport of Canada.[1] In addition, ice hockey is the most popular winter sport in Belarus, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Finland, Latvia, Russia, Slovakia, Sweden, and Switzerland. North America's National Hockey League (NHL) is the highest level for men's ice hockey and the strongest professional ice hockey league in the world. The Kontinental Hockey League (KHL) is the highest league in Russia and much of Eastern Europe. The International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) is the formal governing body for international ice hockey, with the IIHF managing international tournaments and maintaining the IIHF World Ranking. Worldwide, there are ice hockey federations in 76 countries.[2]

In Canada, the United States, Nordic countries, and some other European countries the sport is known simply as hockey; the name "ice hockey" is used in places where "hockey" more often refers to field hockey, such as countries in South America, Asia, Africa, Australasia, and some European countries including the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Netherlands.[3]

Ice hockey is believed to have evolved from simple stick and ball games played in the 18th and 19th centuries in the United Kingdom and elsewhere. These games were brought to North America and several similar winter games using informal rules were developed, such as shinny and ice polo. The contemporary sport of ice hockey was developed in Canada, most notably in Montreal, where the first indoor hockey game was played on March 3, 1875. Some characteristics of that game, such as the length of the ice rink and the use of a puck, have been retained to this day. Amateur ice hockey leagues began in the 1880s, and professional ice hockey originated around 1900. The Stanley Cup, emblematic of ice hockey club supremacy, was first awarded in 1893 to recognize the Canadian amateur champion and later became the championship trophy of the NHL. In the early 1900s, the Canadian rules were adopted by the Ligue Internationale de Hockey Sur Glace, the precursor of the IIHF and the sport was played for the first time at the Olympics during the 1920 Summer Olympics.

In international competitions, the national teams of six countries (the Big Six) predominate: Canada, Czech Republic, Finland, Russia, Sweden and the United States. Of the 69 medals awarded all-time in men's competition at the Olympics, only seven medals were not awarded to one of those countries (or two of their precursors, the Soviet Union for Russia, and Czechoslovakia for the Czech Republic). In the annual Ice Hockey World Championships, 177 of 201 medals have been awarded to the six nations. Teams outside the Big Six have won only five medals in either competition since 1953.[4][5] The World Cup of Hockey is organized by the National Hockey League and the National Hockey League Players' Association (NHLPA), unlike the annual World Championships and quadrennial Olympic tournament, both run by the International Ice Hockey Federation. World Cup games are played under NHL rules and not those of the IIHF, and the tournament occurs prior to the NHL pre-season, allowing for all NHL players to be available, unlike the World Championships, which overlaps with the NHL's Stanley Cup playoffs. Furthermore, all 12 Women's Olympic and 36 IIHF World Women's Championship medals were awarded to one of these six countries. The Canadian national team or the United States national team have between them won every gold medal of either series.[6][7]

History

Name

In England, field hockey has historically been called simply "hockey" and what was referenced by first appearances in print. The first known mention spelled as "hockey" occurred in the 1772 book Juvenile Sports and Pastimes, to Which Are Prefixed, Memoirs of the Author: Including a New Mode of Infant Education, by Richard Johnson (Pseud. Master Michel Angelo), whose chapter XI was titled "New Improvements on the Game of Hockey".[8] The 1527 Statute of Galway banned a sport called "'hokie'—the hurling of a little ball with sticks or staves". A form of this word was thus being used in the 16th century, though much removed from its current usage.[9]

The belief that hockey was mentioned in a 1363 proclamation by King Edward III of England[10] is based on modern translations of the proclamation, which was originally in Latin and explicitly forbade the games "Pilam Manualem, Pedivam, & Bacularem: & ad Canibucam & Gallorum Pugnam".[11][12] The English historian and biographer John Strype did not use the word "hockey" when he translated the proclamation in 1720, instead translating "Canibucam" as "Cambuck";[13] this may have referred to either an early form of hockey or a game more similar to golf or croquet.[14]

According to the Austin Hockey Association, the word "puck" derives from the Scottish Gaelic puc or the Irish poc (to poke, punch or deliver a blow). "...The blow given by a hurler to the ball with his camán or hurley is always called a puck."[15]

Precursors

Stick-and-ball games date back to pre-Christian times. In Europe, these games included the Irish game of hurling, the closely related Scottish game of shinty and versions of field hockey (including bandy ball, played in England). IJscolf, a game resembling colf on an ice-covered surface, was popular in the Low Countries between the Middle Ages and the Dutch Golden Age. It was played with a wooden curved bat (called a colf or kolf), a wooden or leather ball and two poles (or nearby landmarks), with the objective to hit the chosen point using the fewest strokes. A similar game (knattleikr) had been played for a thousand years or more by the Scandinavian peoples, as documented in the Icelandic sagas. Polo has been referred to as "hockey on horseback".[16] In England, field hockey developed in the late 17th century, and there is evidence that some games of field hockey took place on the ice.[16] These games of "hockey on ice" were sometimes played with a bung (a plug of cork or oak used as a stopper on a barrel). William Pierre Le Cocq stated, in a 1799 letter written in Chesham, England:

I must now describe to you the game of Hockey; we have each a stick turning up at the end. We get a bung. There are two sides one of them knocks one way and the other side the other way. If any one of the sides makes the bung reach that end of the churchyard it is victorious.[17]

A 1797 engraving unearthed by Swedish sport historians Carl Gidén and Patrick Houda shows a person on skates with a stick and bung on the River Thames, probably in December 1796.[18]

British soldiers and immigrants to Canada and the United States brought their stick-and-ball games with them and played them on the ice and snow of winter.

To while away their boredom and to stay in shape they [European colonial soldiers in North America] would play on the frozen rivers and lakes. The British [English] played bandy, the Scots played shinty and golf, the Irish, hurling, while the Dutch soldiers probably pursued ken jaegen. Curiosity led some to try lacrosse. Each group learned the game from the others. The most daring ventured to play on skates. All these contributions nourished a game that was evolving. Hockey was invented by all these people, all these cultures, all these individuals. Hockey is the conclusion of all these beginnings.

— Roch Carrier, "Hockey: Canada's Game", in Vancouver 2010 Official Souvenir Program, pg 42.

In 1825, John Franklin wrote "The game of hockey played on the ice was the morning sport" on Great Bear Lake during one of his Arctic expeditions. A mid-1830s watercolour portrays New Brunswick lieutenant-governor Archibald Campbell and his family with British soldiers on skates playing a stick-on-ice sport. Captain R.G.A. Levinge, a British Army officer in New Brunswick during Campbell's time, wrote about "hockey on ice" on Chippewa Creek (a tributary of the Niagara River) in 1839. In 1843 another British Army officer in Kingston, Ontario wrote, "Began to skate this year, improved quickly and had great fun at hockey on the ice."[19] An 1859 Boston Evening Gazette article referred to an early game of hockey on ice in Halifax that year.[20] An 1835 painting by John O'Toole depicts skaters with sticks and bung on a frozen stream in the American state of West Virginia, at that time still part of Virginia.[18]

In the same era, the Mi'kmaq, a First Nations people of the Canadian Maritimes, also had a stick-and-ball game. Canadian oral histories describe a traditional stick-and-ball game played by the Mi'kmaq, and Silas Tertius Rand (in his 1894 Legends of the Micmacs) describes a Mi'kmaq ball game known as tooadijik. Rand also describes a game played (probably after European contact) with hurleys, known as wolchamaadijik.[21] Sticks made by the Mi'kmaq were used by the British for their games.

Early 19th-century paintings depict shinney (or "shinny"), an early form of hockey with no standard rules which was played in Nova Scotia.[22] Many of these early games absorbed the physical aggression of what the Onondaga called dehuntshigwa'es (lacrosse).[23] Shinney was played on the St. Lawrence River at Montreal and Quebec City, and in Kingston[19] and Ottawa. The number of players was often large. To this day, shinney (derived from "shinty") is a popular Canadian[24] term for an informal type of hockey, either ice or street hockey.

Thomas Chandler Haliburton, in The Attache: Second Series (published in 1844) imagined a dialogue, between two of the novel's characters, which mentions playing "hurly on the long pond on the ice". This has been interpreted by some historians from Windsor, Nova Scotia as reminiscent of the days when the author was a student at King's College School in that town in 1810 and earlier.[20][21] Based on Haliburton's quote, claims were made that modern hockey was invented in Windsor, Nova Scotia, by King's College students and perhaps named after an individual ("Colonel Hockey's game").[25] Others claim that the origins of hockey come from games played in the area of Dartmouth and Halifax in Nova Scotia. However, several references have been found to hurling and shinty being played on the ice long before the earliest references from both Windsor and Dartmouth/Halifax,[26] and the word "hockey" was used to designate a stick-and-ball game at least as far back as 1773, as it was mentioned in the book Juvenile Sports and Pastimes, to Which Are Prefixed, Memoirs of the Author: Including a New Mode of Infant Education by Richard Johnson (Pseud. Master Michel Angelo), whose chapter XI was titled "New Improvements on the Game of Hockey".[27]

Initial development

While the game's origins lie elsewhere, Montreal is at the centre of the development of the sport of contemporary ice hockey, and is recognized as the birthplace of organized ice hockey.[28] On March 3, 1875, the first organized indoor game was played at Montreal's Victoria Skating Rink between two nine-player teams, including James Creighton and several McGill University students. Instead of a ball or bung, the game featured a "flat circular piece of wood"[29] (to keep it in the rink and to protect spectators). The goal posts were 8 feet (2.4 m) apart[29] (today's goals are six feet wide).

In 1876, games played in Montreal were "conducted under the 'Hockey Association' rules";[30] the Hockey Association was England's field hockey organization. In 1877, The Gazette (Montreal) published a list of seven rules, six of which were largely based on six of the Hockey Association's twelve rules, with only minor differences (even the word "ball" was kept); the one added rule explained how disputes should be settled.[31] The McGill University Hockey Club, the first ice hockey club, was founded in 1877[32] (followed by the Quebec Hockey Club in 1878 and the Montreal Victorias in 1881).[33] In 1880, the number of players per side was reduced from nine to seven.[8]

The number of teams grew, enough to hold the first "world championship" of ice hockey at Montreal's annual Winter Carnival in 1883. The McGill team won the tournament and was awarded the Carnival Cup.[34] The game was divided into thirty-minute halves. The positions were now named: left and right wing, centre, rover, point and cover-point, and goaltender. In 1886, the teams competing at the Winter Carnival organized the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHAC), and played a season comprising "challenges" to the existing champion.[35]

In Europe, it is believed that in 1885 the Oxford University Ice Hockey Club was formed to play the first Ice Hockey Varsity Match against traditional rival Cambridge in St. Moritz, Switzerland; however, this is undocumented. The match was won by the Oxford Dark Blues, 6–0;[36][37] the first photographs and team lists date from 1895.[38] This rivalry continues, claiming to be the oldest hockey rivalry in history; a similar claim is made about the rivalry between Queen's University at Kingston and Royal Military College of Kingston, Ontario. Since 1986, considered the 100th anniversary of the rivalry, teams of the two colleges play for the Carr-Harris Cup.[39]

In 1888, the Governor General of Canada, Lord Stanley of Preston (whose sons and daughter were hockey enthusiasts), first attended the Montreal Winter Carnival tournament and was impressed with the game. In 1892, realizing that there was no recognition for the best team in Canada (although a number of leagues had championship trophies), he purchased a silver bowl for use as a trophy. The Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup (which later became known as the Stanley Cup) was first awarded in 1893 to the Montreal Hockey Club, champions of the AHAC; it continues to be awarded annually to the National Hockey League's championship team.[40] Stanley's son Arthur helped organize the Ontario Hockey Association, and Stanley's daughter Isobel was one of the first women to play ice hockey.

By 1893, there were almost a hundred teams in Montreal alone; in addition, there were leagues throughout Canada. Winnipeg hockey players used cricket pads to better protect the goaltender's legs; they also introduced the "scoop" shot, or what is now known as the wrist shot. William Fairbrother, from Ontario, Canada is credited with inventing the ice hockey net in the 1890s.[41] Goal nets became a standard feature of the Canadian Amateur Hockey League (CAHL) in 1900. Left and right defence began to replace the point and cover-point positions in the OHA in 1906.[42]

In the United States, ice polo, played with a ball rather than a puck, was popular during this period; however, by 1893 Yale University and Johns Hopkins University held their first ice hockey matches.[43] American financier Malcolm Greene Chace is credited with being the father of hockey in the United States.[44] In 1892, as an amateur tennis player, Chace visited Niagara Falls, New York for a tennis match, where he met some Canadian hockey players. Soon afterwards, Chace put together a team of men from Yale, Brown, and Harvard, and toured across Canada as captain of this team.[44] The first collegiate hockey match in the United States was played between Yale University and Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Yale, led by captain Chace, beat Hopkins, 2–1.[45] In 1896, the first ice hockey league in the US was formed. The US Amateur Hockey League was founded in New York City, shortly after the opening of the artificial-ice St. Nicholas Rink.

Lord Stanley's five sons were instrumental in bringing ice hockey to Europe, defeating a court team (which included the future Edward VII and George V) at Buckingham Palace in 1895.[46] By 1903, a five-team league had been founded. The Ligue Internationale de Hockey sur Glace was founded in 1908 to govern international competition, and the first European championship was won by Great Britain in 1910. The sport grew further in Europe in the 1920s, after ice hockey became an Olympic sport. Many bandy players switched to hockey so as to be able to compete in the Olympics.[47][48] Bandy remained popular in the Soviet Union, which only started its ice hockey program in the 1950s. In the mid-20th century, the Ligue became the International Ice Hockey Federation.[49]

As the popularity of ice hockey as a spectator sport grew, earlier rinks were replaced by larger rinks. Most of the early indoor ice rinks have been demolished; Montreal's Victoria Rink, built in 1862, was demolished in 1925.[50] Many older rinks succumbed to fire, such as Denman Arena, Dey's Arena, Quebec Skating Rink and Montreal Arena, a hazard of the buildings' wood construction. The Stannus Street Rink in Windsor, Nova Scotia (built in 1897) may be the oldest still in existence; however, it is no longer used for hockey. The Aberdeen Pavilion (built in 1898) in Ottawa was used for hockey in 1904 and is the oldest existing facility that has hosted Stanley Cup games.

The oldest indoor ice hockey arena still in use today for hockey is Boston's Matthews Arena, which was built in 1910. It has been modified extensively several times in its history and is used today by Northeastern University for hockey and other sports. It was the original home rink of the Boston Bruins professional team,[51] itself the oldest United States-based team in the NHL, starting play in the league in today's Matthews Arena on December 1, 1924. Madison Square Garden in New York City, built in 1968, is the oldest continuously-operating arena in the NHL.[52]

Professional era

Professional hockey has existed since the early 20th century. By 1902, the Western Pennsylvania Hockey League was the first to employ professionals. The league joined with teams in Michigan and Ontario to form the first fully professional league—the International Professional Hockey League (IPHL)—in 1904. The WPHL and IPHL hired players from Canada; in response, Canadian leagues began to pay players (who played with amateurs). The IPHL, cut off from its largest source of players, disbanded in 1907. By then, several professional hockey leagues were operating in Canada (with leagues in Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec).

In 1910, the National Hockey Association (NHA) was formed in Montreal. The NHA would further refine the rules: dropping the rover position, dividing the game into three 20-minute periods and introducing minor and major penalties. After re-organizing as the National Hockey League in 1917, the league expanded into the United States, starting with the Boston Bruins in 1924.

Professional hockey leagues developed later in Europe, but amateur leagues leading to national championships were in place. One of the first was the Swiss National League A, founded in 1916. Today, professional leagues have been introduced in most countries of Europe. Top European leagues include the Kontinental Hockey League, the Czech Extraliga, the Finnish Liiga and the Swedish Hockey League.

Game

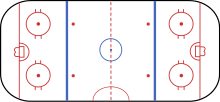

While the general characteristics of the game stay the same wherever it is played, the exact rules depend on the particular code of play being used. The two most important codes are those of the IIHF[53] and the NHL.[54] Both of the codes, and others, originated from Canadian rules of ice hockey of the early 20th Century.

Ice hockey is played on a hockey rink. During normal play, there are six players per side on the ice at any time, one of them being the goaltender, each of whom is on ice skates. The objective of the game is to score goals by shooting a hard vulcanized rubber disc, the puck, into the opponent's goal net, which is placed at the opposite end of the rink. The players use their sticks to pass or shoot the puck.

Within certain restrictions, players may redirect the puck with any part of their body. Players may not hold the puck in their hand and are prohibited from using their hands to pass the puck to their teammates unless they are in the defensive zone. Players are also prohibited from kicking the puck into the opponent's goal, though unintentional redirections off the skate are permitted. Players may not intentionally bat the puck into the net with their hands.

Hockey is an off-side game, meaning that forward passes are allowed, unlike in rugby. Before the 1930s, hockey was an on-side game, meaning that only backward passes were allowed. Those rules favoured individual stick-handling as a key means of driving the puck forward. With the arrival of offside rules, the forward pass transformed hockey into a true team sport, where individual performance diminished in importance relative to team play, which could now be coordinated over the entire surface of the ice as opposed to merely rearward players.[55]

The six players on each team are typically divided into three forwards, two defencemen, and a goaltender. The term skaters is typically used to describe all players who are not goaltenders. The forward positions consist of a centre and two wingers: a left wing and a right wing. Forwards often play together as units or lines, with the same three forwards always playing together. The defencemen usually stay together as a pair generally divided between left and right. Left and right side wingers or defencemen are generally positioned as such, based on the side on which they carry their stick. A substitution of an entire unit at once is called a line change. Teams typically employ alternate sets of forward lines and defensive pairings when short-handed or on a power play. The goaltender stands in a, usually blue, semi-circle called the crease in the defensive zone keeping pucks from going in. Substitutions are permitted at any time during the game, although during a stoppage of play the home team is permitted the final change. When players are substituted during play, it is called changing on the fly. A new NHL rule added in the 2005–06 season prevents a team from changing their line after they ice the puck.

The boards surrounding the ice help keep the puck in play and they can also be used as tools to play the puck. Players are permitted to bodycheck opponents into the boards as a means of stopping progress. The referees, linesmen and the outsides of the goal are "in play" and do not cause a stoppage of the game when the puck or players are influenced (by either bouncing or colliding) into them. Play can be stopped if the goal is knocked out of position. Play often proceeds for minutes without interruption. When play is stopped, it is restarted with a faceoff. Two players face each other and an official drops the puck to the ice, where the two players attempt to gain control of the puck. Markings (circles) on the ice indicate the locations for the faceoff and guide the positioning of players.

The three major rules of play in ice hockey that limit the movement of the puck: offside, icing, and the puck going out of play. A player is offside if he enters his opponent's zone before the puck itself. Under many situations, a player may not "ice the puck", shoot the puck all the way across both the centre line and the opponent's goal line. The puck goes out of play whenever it goes past the perimeter of the ice rink (onto the player benches, over the glass, or onto the protective netting above the glass) and a stoppage of play is called by the officials using whistles. It also does not matter if the puck comes back onto the ice surface from those areas as the puck is considered dead once it leaves the perimeter of the rink.

Under IIHF rules, each team may carry a maximum of 20 players and two goaltenders on their roster. NHL rules restrict the total number of players per game to 18, plus two goaltenders. In the NHL, the players are usually divided into four lines of three forwards, and into three pairs of defencemen. On occasion, teams may elect to substitute an extra defenceman for a forward. The seventh defenceman may play as a substitute defenceman, spend the game on the bench, or if a team chooses to play four lines then this seventh defenceman may see ice-time on the fourth line as a forward.

Periods and overtime

A professional game consists of three periods of twenty minutes, the clock running only when the puck is in play. The teams change ends after each period of play, including overtime. Recreational leagues and children's leagues often play shorter games, generally with three shorter periods of play.

.jpg)

Various procedures are used if a tie occurs. In tournament play, as well as in the NHL playoffs, North Americans favour sudden death overtime, in which the teams continue to play twenty-minute periods until a goal is scored. Up until the 1999–2000 season regular season NHL games were settled with a single five-minute sudden death period with five players (plus a goalie) per side, with both teams awarded one point in the standings in the event of a tie. With a goal, the winning team would be awarded two points and the losing team none (just as if they had lost in regulation).

From the 1999–2000 until the 2003–04 seasons, the National Hockey League decided ties by playing a single five-minute sudden death overtime period with each team having four skaters per side (plus the goalie). In the event of a tie, each team would still receive one point in the standings but in the event of a victory the winning team would be awarded two points in the standings and the losing team one point. The idea was to discourage teams from playing for a tie, since previously some teams might have preferred a tie and 1 point to risking a loss and zero points. The only exception to this rule is if a team opts to pull their goalie in exchange for an extra skater during overtime and is subsequently scored upon (an empty net goal), in which case the losing team receives no points for the overtime loss. Since the 2015–16 season, the single five-minute sudden death overtime session involves three skaters on each side. Since three skaters must always be on the ice in an NHL game, the consequences of penalties are slightly different from those during regulation play. If a team is on a powerplay when overtime begins, that team will play with more than three skaters (usually four, very rarely five) until the expiration of the penalty. Any penalty during overtime that would result in a team losing a skater during regulation instead causes the non-penalized team to add a skater. Once the penalized team's penalty ends, the number of skaters on each side is adjusted accordingly, with the penalized team adding a skater in regulation and the non-penalized team subtracting a skater in overtime. This goes until the next stoppage of play.[56]

International play and several North American professional leagues, including the NHL (in the regular season), now use an overtime period identical to that from 1999–2000 to 2003–04 followed by a penalty shootout. If the score remains tied after an extra overtime period, the subsequent shootout consists of three players from each team taking penalty shots. After these six total shots, the team with the most goals is awarded the victory. If the score is still tied, the shootout then proceeds to a sudden death format. Regardless of the number of goals scored during the shootout by either team, the final score recorded will award the winning team one more goal than the score at the end of regulation time. In the NHL if a game is decided in overtime or by a shootout the winning team is awarded two points in the standings and the losing team is awarded one point. Ties no longer occur in the NHL.

The overtime mode for the NHL playoffs differ from the regular season. In the playoffs there are no shootouts nor ties. If a game is tied after regulation an additional 20 minutes of 5 on 5 sudden death overtime will be added. In case of a tied game after the overtime, multiple 20-minute overtimes will be played until a team scores, which wins the match. Since 2019, the IIHF World Championships and the medal games in the Olympics use the same format, but in a 3-on-3 format.

Penalties

In ice hockey, infractions of the rules lead to play stoppages whereby the play is restarted at a face off. Some infractions result in the imposition of a penalty to a player or team. In the simplest case, the offending player is sent to the penalty box and their team has to play with one less player on the ice for a designated amount of time. Minor penalties last for two minutes, major penalties last for five minutes, and a double minor penalty is two consecutive penalties of two minutes duration. A single minor penalty may be extended by a further two minutes for causing visible injury to the victimized player. This is usually when blood is drawn during high sticking. Players may be also assessed personal extended penalties or game expulsions for misconduct in addition to the penalty or penalties their team must serve. The team that has been given a penalty is said to be playing short-handed while the opposing team is on a power play.

A two-minute minor penalty is often charged for lesser infractions such as tripping, elbowing, roughing, high-sticking, delay of the game, too many players on the ice, boarding, illegal equipment, charging (leaping into an opponent or body-checking him after taking more than two strides), holding, holding the stick (grabbing an opponent's stick), interference, hooking, slashing, kneeing, unsportsmanlike conduct (arguing a penalty call with referee, extremely vulgar or inappropriate verbal comments), "butt-ending" (striking an opponent with the knob of the stick—a very rare penalty), "spearing", or cross-checking. As of the 2005–2006 season, a minor penalty is also assessed for diving, where a player embellishes or simulates an offence. More egregious fouls may be penalized by a four-minute double-minor penalty, particularly those that injure the victimized player. These penalties end either when the time runs out or when the other team scores during the power play. In the case of a goal scored during the first two minutes of a double-minor, the penalty clock is set down to two minutes upon a score, effectively expiring the first minor penalty.

.jpg)

A five-minute major penalties are called for especially violent instances of most minor infractions that result in intentional injury to an opponent, or when a minor penalty results in visible injury (such as bleeding), as well as for fighting. Major penalties are always served in full; they do not terminate on a goal scored by the other team. Major penalties assessed for fighting are typically offsetting, meaning neither team is short-handed and the players exit the penalty box upon a stoppage of play following the expiration of their respective penalties. The foul of boarding (defined as "check[ing] an opponent in such a manner that causes the opponent to be thrown violently in the boards")[57] is penalized either by a minor or major penalty at the discretion of the referee, based on the violent state of the hit. A minor or major penalty for boarding is often assessed when a player checks an opponent from behind and into the boards.

Some varieties of penalties do not always require the offending team to play a man short. Concurrent five-minute major penalties in the NHL usually result from fighting. In the case of two players being assessed five-minute fighting majors, both the players serve five minutes without their team incurring a loss of player (both teams still have a full complement of players on the ice). This differs with two players from opposing sides getting minor penalties, at the same time or at any intersecting moment, resulting from more common infractions. In this case, both teams will have only four skating players (not counting the goaltender) until one or both penalties expire (if one penalty expires before the other, the opposing team gets a power play for the remainder of the time); this applies regardless of current pending penalties. However, in the NHL, a team always has at least three skaters on the ice. Thus, ten-minute misconduct penalties are served in full by the penalized player, but his team may immediately substitute another player on the ice unless a minor or major penalty is assessed in conjunction with the misconduct (a two-and-ten or five-and-ten). In this case, the team designates another player to serve the minor or major; both players go to the penalty box, but only the designee may not be replaced, and he is released upon the expiration of the two or five minutes, at which point the ten-minute misconduct begins. In addition, game misconducts are assessed for deliberate intent to inflict severe injury on an opponent (at the officials' discretion), or for a major penalty for a stick infraction or repeated major penalties. The offending player is ejected from the game and must immediately leave the playing surface (he does not sit in the penalty box); meanwhile, if an additional minor or major penalty is assessed, a designated player must serve out of that segment of the penalty in the box (similar to the above-mentioned "two-and-ten"). In some rare cases, a player may receive up to nineteen minutes in penalties for one string of plays. This could involve receiving a four-minute double minor penalty, getting in a fight with an opposing player who retaliates, and then receiving a game misconduct after the fight. In this case, the player is ejected and two teammates must serve the double-minor and major penalties.

A penalty shot is awarded to a player when the illegal actions of another player stop a clear scoring opportunity, most commonly when the player is on a breakaway. A penalty shot allows the obstructed player to pick up the puck on the centre red-line and attempt to score on the goalie with no other players on the ice, to compensate for the earlier missed scoring opportunity. A penalty shot is also awarded for a defender other than the goaltender covering the puck in the goal crease, a goaltender intentionally displacing his own goal posts during a breakaway to avoid a goal, a defender intentionally displacing his own goal posts when there is less than two minutes to play in regulation time or at any point during overtime, or a player or coach intentionally throwing a stick or other object at the puck or the puck carrier and the throwing action disrupts a shot or pass play.

Officials also stop play for puck movement violations, such as using one's hands to pass the puck in the offensive end, but no players are penalized for these offences. The sole exceptions are deliberately falling on or gathering the puck to the body, carrying the puck in the hand, and shooting the puck out of play in one's defensive zone (all penalized two minutes for delay of game).

In the NHL, a unique penalty applies to the goalies. The goalies now are forbidden to play the puck in the "corners" of the rink near their own net. This will result in a two-minute penalty against the goalie's team. Only in the area in-front of the goal line and immediately behind the net (marked by two red lines on either side of the net) the goalie can play the puck.

An additional rule that has never been a penalty, but was an infraction in the NHL before recent rules changes, is the two-line offside pass. Prior to the 2005–06 NHL season, play was stopped when a pass from inside a team's defending zone crossed the centre line, with a face-off held in the defending zone of the offending team. Now, the centre line is no longer used in the NHL to determine a two-line pass infraction, a change that the IIHF had adopted in 1998. Players are now able to pass to teammates who are more than the blue and centre ice red line away.

The NHL has taken steps to speed up the game of hockey and create a game of finesse, by retreating from the past when illegal hits, fights, and "clutching and grabbing" among players were commonplace. Rules are now more strictly enforced, resulting in more penalties, which in turn provides more protection to the players and facilitates more goals being scored. The governing body for United States' amateur hockey has implemented many new rules to reduce the number of stick-on-body occurrences, as well as other detrimental and illegal facets of the game ("zero tolerance").

In men's hockey, but not in women's, a player may use his hip or shoulder to hit another player if the player has the puck or is the last to have touched it. This use of the hip and shoulder is called body checking. Not all physical contact is legal—in particular, hits from behind, hits to the head and most types of forceful stick-on-body contact are illegal.

.jpg)

A delayed penalty call occurs when a penalty offence is committed by the team that does not have possession of the puck. In this circumstance the team with possession of the puck is allowed to complete the play; that is, play continues until a goal is scored, a player on the opposing team gains control of the puck, or the team in possession commits an infraction or penalty of their own. Because the team on which the penalty was called cannot control the puck without stopping play, it is impossible for them to score a goal. In these cases, the team in possession of the puck can pull the goalie for an extra attacker without fear of being scored on. However, it is possible for the controlling team to mishandle the puck into their own net. If a delayed penalty is signalled and the team in possession scores, the penalty is still assessed to the offending player, but not served. In 2012, this rule was changed by the United States' National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) for college level hockey. In college games, the penalty is still enforced even if the team in possession scores.[58]

Officials

A typical game of hockey is governed by two to four officials on the ice, charged with enforcing the rules of the game. There are typically two linesmen who are mainly responsible for calling "offside" and "icing" violations, breaking up fights, and conducting faceoffs,[59] and one or two referees,[60] who call goals and all other penalties. Linesmen can, however, report to the referee(s) that a penalty should be assessed against an offending player in some situations.[61] The restrictions on this practice vary depending on the governing rules. On-ice officials are assisted by off-ice officials who act as goal judges, time keepers, and official scorers.

The most widespread system in use today is the "three-man system", that uses one referee and two linesmen. Another less commonly used system is the two referee and one linesman system. This system is very close to the regular three-man system except for a few procedure changes. With the first being the National Hockey League, a number of leagues have started to implement the "four-official system", where an additional referee is added to aid in the calling of penalties normally difficult to assess by one single referee. The system is now used in every NHL game since 2001, at IIHF World Championships, the Olympics and in many professional and high-level amateur leagues in North America and Europe.

Officials are selected by the league they work for. Amateur hockey leagues use guidelines established by national organizing bodies as a basis for choosing their officiating staffs. In North America, the national organizing bodies Hockey Canada and USA Hockey approve officials according to their experience level as well as their ability to pass rules knowledge and skating ability tests. Hockey Canada has officiating levels I through VI.[62] USA Hockey has officiating levels 1 through 4.[63]

Equipment

Since men's ice hockey is a full contact sport, body checks are allowed so injuries are a common occurrence. Protective equipment is mandatory and is enforced in all competitive situations. This includes a helmet with either a visor or a full face mask, shoulder pads, elbow pads, mouth guard, protective gloves, heavily padded shorts (also known as hockey pants) or a girdle, athletic cup (also known as a jock, for males; and jill, for females), shin pads, skates, and (optionally) a neck protector.

Goaltenders use different equipment. With hockey pucks approaching them at speeds of up to 100 mph (160 km/h) they must wear equipment with more protection. Goaltenders wear specialized goalie skates (these skates are built more for movement side to side rather than forwards and backwards), a jock or jill, large leg pads (there are size restrictions in certain leagues), blocking glove, catching glove, a chest protector, a goalie mask, and a large jersey. Goaltenders' equipment has continually become larger and larger, leading to fewer goals in each game and many official rule changes.

Hockey skates are optimized for physical acceleration, speed and manoeuvrability. This includes rapid starts, stops, turns, and changes in skating direction. In addition, they must be rigid and tough to protect the skater's feet from contact with other skaters, sticks, pucks, the boards, and the ice itself. Rigidity also improves the overall manoeuvrability of the skate. Blade length, thickness (width), and curvature (rocker/radius (front to back) and radius of hollow (across the blade width) are quite different from speed or figure skates. Hockey players usually adjust these parameters based on their skill level, position, and body type. The blade width of most skates are about 1⁄8 inch (3.2 mm) thick.

The hockey stick consists of a long, relatively wide, and slightly curved flat blade, attached to a shaft. The curve itself has a big impact on its performance. A deep curve allows for lifting the puck easier while a shallow curve allows for easier backhand shots. The flex of the stick also impacts the performance. Typically, a less flexible stick is meant for a stronger player since the player is looking for the right balanced flex that allows the stick to flex easily while still having a strong "whip-back" which sends the puck flying at high speeds. It is quite distinct from sticks in other sports games and most suited to hitting and controlling the flat puck. Its unique shape contributed to the early development of the game.

Injury

Ice hockey is a full contact sport and carries a high risk of injury. Players are moving at speeds around approximately 20–30 mph (30–50 km/h) and quite a bit of the game revolves around the physical contact between the players. Skate blades, hockey sticks, shoulder contact, hip contact, and hockey pucks can all potentially cause injuries. The types of injuries associated with hockey include: lacerations, concussions, contusions, ligament tears, broken bones, hyperextensions, and muscle strains. Women's ice hockey players are allowed to contact other players but are not allowed to body check.

.jpg)

Compared to athletes who play other sports, ice hockey players are at higher risk of overuse injuries and injuries caused by early sports specialization by teenagers.[64]

According to the Hughston Health Alert, "Lacerations to the head, scalp, and face are the most frequent types of injury [in hockey]."[65] Even a shallow cut to the head results in a loss of a large amount of blood. Direct trauma to the head is estimated to account for 80% of all hockey injuries as a result of player contact with other players or hockey equipment.[65]

One of the leading causes of head injury is body checking from behind. Due to the danger of delivering a check from behind, many leagues, including the NHL have made this a major and game misconduct penalty (called "boarding"). Another type of check that accounts for many of the player-to-player contact concussions is a check to the head resulting in a misconduct penalty (called "head contact"). A check to the head can be defined as delivering a hit while the receiving player's head is down and their waist is bent and the aggressor is targeting the opponent player's head.

The most dangerous result of a head injury in hockey can be classified as a concussion. Most concussions occur during player-to-player contact rather than when a player is checked into the boards. Checks to the head have accounted for nearly 50% of concussions that players in the National Hockey League have suffered. In recent years, the NHL has implemented new rules which penalize and suspend players for illegal checks to the heads, as well as checks to unsuspecting players. Concussions that players suffer may go unreported because there is no obvious physical signs if a player is not knocked unconscious. This can prove to be dangerous if a player decides to return to play without receiving proper medical attention. Studies show that ice hockey causes 44.3% of all traumatic brain injuries among Canadian children.[66] In severe cases, the traumatic brain injuries are capable of resulting in death. Occurrences of death from these injuries are rare.

Tactics

Checking

An important defensive tactic is checking—attempting to take the puck from an opponent or to remove the opponent from play. Stick checking, sweep checking, and poke checking are legal uses of the stick to obtain possession of the puck. The neutral zone trap is designed to isolate the puck carrier in the neutral zone preventing him from entering the offensive zone. Body checking is using one's shoulder or hip to strike an opponent who has the puck or who is the last to have touched it (the last person to have touched the puck is still legally "in possession" of it, although a penalty is generally called if he is checked more than two seconds after his last touch). Body checking is also a penalty in certain leagues in order to reduce the chance of injury to players. Often the term checking is used to refer to body checking, with its true definition generally only propagated among fans of the game.

Offensive tactics

Offensive tactics include improving a team's position on the ice by advancing the puck out of one's zone towards the opponent's zone, progressively by gaining lines, first your own blue line, then the red line and finally the opponent's blue line. NHL rules instated for the 2006 season redefined the offside rule to make the two-line pass legal; a player may pass the puck from behind his own blue line, past both that blue line and the centre red line, to a player on the near side of the opponents' blue line. Offensive tactics are designed ultimately to score a goal by taking a shot. When a player purposely directs the puck towards the opponent's goal, he or she is said to "shoot" the puck.

.jpg)

A deflection is a shot that redirects a shot or a pass towards the goal from another player, by allowing the puck to strike the stick and carom towards the goal. A one-timer is a shot struck directly off a pass, without receiving the pass and shooting in two separate actions. Headmanning the puck, also known as breaking out, is the tactic of rapidly passing to the player farthest down the ice. Loafing, also known as cherry-picking, is when a player, usually a forward, skates behind an attacking team, instead of playing defence, in an attempt to create an easy scoring chance.

A team that is losing by one or two goals in the last few minutes of play will often elect to pull the goalie; that is, remove the goaltender and replace him or her with an extra attacker on the ice in the hope of gaining enough advantage to score a goal. However, it is an act of desperation, as it sometimes leads to the opposing team extending their lead by scoring a goal in the empty net.

One of the most important strategies for a team is their forecheck. Forechecking is the act of attacking the opposition in their defensive zone. Forechecking is an important part of the dump and chase strategy (i.e. shooting the puck into the offensive zone and then chasing after it). Each team will use their own unique system but the main ones are: 2–1–2, 1–2–2, and 1–4. The 2–1–2 is the most basic forecheck system where two forwards will go in deep and pressure the opposition's defencemen, the third forward stays high and the two defencemen stay at the blueline. The 1–2–2 is a bit more conservative system where one forward pressures the puck carrier and the other two forwards cover the oppositions' wingers, with the two defencemen staying at the blueline. The 1–4 is the most defensive forecheck system, referred to as the neutral zone trap, where one forward will apply pressure to the puck carrier around the oppositions' blueline and the other 4 players stand basically in a line by their blueline in hopes the opposition will skate into one of them. Another strategy is the left wing lock, which has two forwards pressure the puck and the left wing and the two defencemen stay at the blueline.

There are many other little tactics used in the game of hockey. Cycling moves the puck along the boards in the offensive zone to create a scoring chance by making defenders tired or moving them out of position. Pinching is when a defenceman pressures the opposition's winger in the offensive zone when they are breaking out, attempting to stop their attack and keep the puck in the offensive zone. A saucer pass is a pass used when an opposition's stick or body is in the passing lane. It is the act of raising the puck over the obstruction and having it land on a teammate's stick.

A deke, short for "decoy", is a feint with the body or stick to fool a defender or the goalie. Many modern players, such as Pavel Datsyuk, Sidney Crosby and Patrick Kane, have picked up the skill of "dangling", which is fancier deking and requires more stick handling skills.

Fights

Although fighting is officially prohibited in the rules, it is not an uncommon occurrence at the professional level, and its prevalence has been both a target of criticism and a considerable draw for the sport. At the professional level in North America fights are unofficially condoned. Enforcers and other players fight to demoralize the opposing players while exciting their own, as well as settling personal scores. A fight will also break out if one of the team's skilled players gets hit hard or someone receives what the team perceives as a dirty hit. The amateur game penalizes fisticuffs more harshly, as a player who receives a fighting major is also assessed at least a 10-minute misconduct penalty (NCAA and some Junior leagues) or a game misconduct penalty and suspension (high school and younger, as well as some casual adult leagues).[67] Crowds seem to like fighting in ice hockey and cheer when fighting erupts.[68]

Women's ice hockey

Ice hockey is one of the fastest growing women's sports in the world, with the number of participants increasing by 400 percent from 1995 to 2005.[69] In 2011, Canada had 85,827 women players,[70] United States had 65,609,[71] Finland 4,760,[72] Sweden 3,075[73] and Switzerland 1,172.[74] While there are not as many organized leagues for women as there are for men, there exist leagues of all levels, including the Canadian Women's Hockey League (CWHL), Western Women's Hockey League, National Women's Hockey League (NWHL), Mid-Atlantic Women's Hockey League, and various European leagues; as well as university teams, national and Olympic teams, and recreational teams. The IIHF holds IIHF World Women's Championships tournaments in several divisions; championships are held annually, except that the top flight does not play in Olympic years.[75]

The chief difference between women's and men's ice hockey is that body checking is prohibited in women's hockey. After the 1990 Women's World Championship, body checking was eliminated in women's hockey. In current IIHF women's competition, body checking is either a minor or major penalty, decided at the referee's discretion.[76] In addition, players in women's competition are required to wear protective full-face masks.[76]

In Canada, to some extent ringette has served as the female counterpart to ice hockey, in the sense that traditionally, boys have played hockey while girls have played ringette.[77]

History

Women are known to have played the game in the 19th century. Several games were recorded in the 1890s in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The women of Lord Stanley's family were known to participate in the game of ice hockey on the outdoor ice rink at Rideau Hall, the residence of Canada's Governor-General.

The game developed at first without an organizing body. A tournament in 1902 between Montreal and Trois-Rivieres was billed as the first championship tournament. Several tournaments, such as at the Banff Winter Carnival, were held in the early 20th century and numerous women's teams such as the Seattle Vamps and Vancouver Amazons existed. Organizations started to develop in the 1920s, such as the Ladies Ontario Hockey Association, and later, the Dominion Women's Amateur Hockey Association. Starting in the 1960s, the game spread to universities. Today, the sport is played from youth through adult leagues, and in the universities of North America and internationally. There have been two major professional women's hockey leagues to have paid its players: the National Women's Hockey League with teams in the United States and the Canadian Women's Hockey League with teams in Canada, China, and the United States.

The first women's world championship tournament, albeit unofficial, was held in 1987 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. This was followed by the first IIHF World Championship in 1990 in Ottawa. Women's ice hockey was added as a medal sport at the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, Japan. The United States won the gold, Canada won the silver and Finland won the bronze medal.[78] Canada won in 2002, 2006, 2010, and 2014, and also reached the gold medal game in 2018, where it lost in a shootout to the United States, their first loss in a competitive Olympic game since 2002.[79]

The United States Hockey League (USHL) welcomed the first female professional ice hockey player in 1969–70, when the Marquette Iron Rangers signed Karen Koch.[80] One woman, Manon Rhéaume, has played in an NHL pre-season game as a goaltender for the Tampa Bay Lightning against the St. Louis Blues. In 2003, Hayley Wickenheiser played with the Kirkkonummi Salamat in the Finnish men's Suomi-sarja league. Several women have competed in North American minor leagues, including Rhéaume, goaltenders Kelly Dyer and Erin Whitten and defenceman Angela Ruggiero.

With interest in women's ice hockey growing, between 2007 and 2010 the number of registered female players worldwide grew from 153,665 to 170,872. Women's hockey is on the rise in almost every part of the world and there are teams in North America, Europe, Asia, Oceania, Africa and Latin America.[81]

The future of international women's ice hockey was discussed at the World Hockey Summit in 2010, and IIHF member associations could work together.[82] International Olympic Committee president Jacques Rogge stated that the women's hockey tournament might be eliminated from the Olympics since the event was not competitively balanced, and dominated by Canada and the United States.[83] Team Canada captain Hayley Wickenheiser explained that the talent gap between the North American and European countries was due to the presence of women's professional leagues in North America, along with year-round training facilities. She stated the European players were talented, but their respective national team programs were not given the same level of support as the European men's national teams, or the North American women's national teams.[84] She stressed the need for women to have their own professional league which would be for the benefit of international hockey.[85]

Women's Hockey Leagues

The primary women's professional hockey league in North America is the National Women's Hockey League (NWHL) with five teams located in the United States and one in Canada.[86] From 2007 until 2019 the Canadian Women's Hockey League (CWHL) operated with teams in Canada, the United States and China.[87]

CWHL

The CWHL was founded in 2007 and originally consisted of seven teams in Canada, but had several membership changes including adding a team in the United States in 2010. When the league launched, its players were only compensated for travel and equipment. The league began paying its players a stipend in the 2017–18 season when the league launched its first teams in China. For the league's 2018–19 season, there were six teams consisting of the Calgary Inferno, Les Canadiennes de Montreal, Markham Thunder, Shenzhen KRS Vanke Rays, Toronto Furies, and the Worcester Blades.[87] The CWHL ceased operations in 2019 citing unsustainable business operations.

NWHL

The NWHL was founded in 2015 with four teams in the Northeast United States and was the first North American women's league to pay its players. The league expanded to five teams in 2018 with the addition of the formerly independent Minnesota Whitecaps.[88] The league had conditionally approved of Canadian expansion teams in Montreal and Toronto following the dissolution of the CWHL, but lack of investors has caused the postponement of any further expansion. On April 22, 2020, the NWHL officially announced that Toronto was awarded an expansion team for the 2020–21 season growing the league to six teams. The six teams in the league are the Boston Pride, Buffalo Beauts, Connecticut Whale, Metropolitan Riveters, Minnesota Whitecaps, and the Toronto Six.

Leagues and championships

The following is a list of professional ice hockey leagues by attendance:

| League | Country | Notes | Average Attendance[89] for 2018–19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Hockey League (NHL) | 32 teams in 2021–22 season | 17,406 | |

| National League | 6,949 | ||

| Deutsche Eishockey Liga | 6,215 | ||

| Kontinental Hockey League | Successor to Russian Superleague and Soviet Championship League | 6,397 | |

| American Hockey League | Developmental league for NHL | 5,672 | |

| Swedish Hockey League | Known as Elitserien until 2013 | 5,936 | |

| Czech Extraliga | Formed from the split of the Czechoslovak First Ice Hockey League | 5,401 | |

| Liiga | Originally SM-sarja from 1928 to 1975. Known as SM-Liiga from 1975 to 2013 | 4,232 | |

| Western Hockey League | Junior league | 4,295 | |

| ECHL | 4,365 | ||

| Ontario Hockey League | Junior league | 3,853 | |

| NCAA Men's Division I Ice Hockey Tournament | Amateur intercollegiate competition | 3,281 | |

| Quebec Major Junior Hockey League | Junior league | 3,271 | |

| Champions Hockey League | Europe-wide championship tournament league. Successor to European Trophy and Champions Hockey League | 3,397[90] | |

| Southern Professional Hockey League | 3,116 | ||

| Austrian Hockey League | 2,970 | ||

| Elite Ice Hockey League | Teams in all of the home nations: England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland | 2,850 | |

| DEL2 | Second division of Germany | 2,511 | |

| United States Hockey League | Amateur junior league | 2,367 | |

| HockeyAllsvenskan | Second division of Sweden | 2,713 | |

| GET-ligaen | 1,827 | ||

| Slovak Extraliga | Formed from the split of the Czechoslovak First Ice Hockey League | 1,663 | |

| Ligue Magnus | 1,716 | ||

| Supreme Hockey League (VHL) | Second division of Russia and partial development league for the KHL | 1,766 | |

| Swiss League | Second division of Switzerland | 1,845 | |

| WSM Liga | Second division of Czechia | 1,674 | |

| Latvian Hockey Higher League | 1,354 | ||

| Metal Ligaen | 1,525 | ||

| National Women's Hockey League | Formed in 2015 | 954[91] | |

| Asia League | 976 | ||

| Mestis | Successor to I-Divisioona, Second division of Finland | 762 | |

| Federal Prospects Hockey League | 1,546[92] | ||

| BeNe League | Formed in 2015 with teams from Dutch Eredivisie and Belgian Hockey League | 784 | |

| Polska Hokej Liga | 751 | ||

| Erste Liga | 601 | ||

| Alps Hockey League | Formed in 2016 with the merger of Italy's Serie A and the joint Austrian–Slovenian Inter-National League | 734 | |

| Belarusian Extraleague | 717 |

Club competition

North America

.jpg)

The NHL is by far the best attended and most popular ice hockey league in the world, and is among the major professional sports leagues in the United States and Canada. The league's history began after Canada's National Hockey Association decided to disband in 1917; the result was the creation of the National Hockey League with four teams. The league expanded to the United States beginning in 1924 and had as many as 10 teams before contracting to six teams by 1942–43. In 1967, the NHL doubled in size to 12 teams, undertaking one of the greatest expansions in professional sports history. A few years later, in 1972, a new 12-team league, the World Hockey Association (WHA) was formed and due to its ensuing rivalry with the NHL, it caused an escalation in players salaries. In 1979, the 17-team NHL merged with the WHA creating a 21-team league.[93] By 2017, the NHL had expanded to 31 teams, and after a realignment in 2013, these teams were divided into two conferences and four divisions.[94] The league is expected to expand to 32 teams by 2021.

The American Hockey League (AHL), sometimes referred to as "The A",[95] is the primary developmental professional league for players aspiring to enter the NHL. It comprises 31 teams from the United States and Canada. It is run as a "farm league" to the NHL, with the vast majority of AHL players under contract to an NHL team. The ECHL (called the East Coast Hockey League before the 2003–04 season) is a mid-level minor league in the United States with a few players under contract to NHL or AHL teams.

As of 2019, there are three minor professional leagues with no NHL affiliations: the Federal Prospects Hockey League (FPHL), Ligue Nord-Américaine de Hockey (LNAH), and the Southern Professional Hockey League (SPHL).

U Sports ice hockey is the highest level of play at the Canadian university level under the auspices of U Sports, Canada's governing body for university sports. As these players compete at the university level, they are obligated to follow the rule of standard eligibility of five years. In the United States especially, college hockey is popular and the best university teams compete in the annual NCAA Men's Ice Hockey Championship. The American Collegiate Hockey Association is composed of college teams at the club level.

In Canada, the Canadian Hockey League is an umbrella organization comprising three major junior leagues: the Ontario Hockey League, the Western Hockey League, and the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League. It attracts players from Canada, the United States and Europe. The major junior players are considered amateurs as they are under 21-years-old and not paid a salary, however, they do get a stipend and play a schedule similar to a professional league. Typically, the NHL drafts many players directly from the major junior leagues.

In the United States, the United States Hockey League (USHL) is the highest junior league. Players in this league are also amateur with players required to be under 21-years old, but do not get a stipend, which allows players to retain their eligibility for participation in NCAA ice hockey.

Eurasia

The Kontinental Hockey League (KHL) is the largest and most popular ice hockey league in Eurasia. The league is the direct successor to the Russian Super League, which in turn was the successor to the Soviet League, the history of which dates back to the Soviet adoption of ice hockey in the 1940s. The KHL was launched in 2008 with clubs predominantly from Russia, but featuring teams from other post-Soviet states. The league expanded beyond the former Soviet countries beginning in the 2011–12 season, with clubs in Croatia and Slovakia. The KHL currently comprises member clubs based in Belarus (1), China (1), Finland (1), Latvia (1), Kazakhstan (1) and Russia (19) for a total of 24.

The second division of hockey in Eurasia is the Supreme Hockey League (VHL). This league features 24 teams from Russia and 2 from Kazakhstan. This league is currently being converted to a farm league for the KHL, similarly to the AHL's function in relation to the NHL. The third division is the Russian Hockey League, which features only teams from Russia. The Asia League, an international ice hockey league featuring clubs from China, Japan, South Korea, and the Russian Far East, is the successor to the Japan Ice Hockey League.

The highest junior league in Eurasia is the Junior Hockey League (MHL). It features 32 teams from post-Soviet states, predominantly Russia. The second tier to this league is the Junior Hockey League Championships (MHL-B).

Europe

.jpg)

Several countries in Europe have their own top professional senior leagues. Many future KHL and NHL players start or end their professional careers in these leagues. The National League A in Switzerland, Swedish Hockey League in Sweden, Liiga in Finland, and Czech Extraliga in the Czech Republic are all very popular in their respective countries.

Beginning in the 2014–15 season, the Champions Hockey League was launched, a league consisting of first-tier teams from several European countries, running parallel to the teams' domestic leagues. The competition is meant to serve as a Europe-wide ice hockey club championship. The competition is a direct successor to the European Trophy and is related to the 2008–09 tournament of the same name.

There are also several annual tournaments for clubs, held outside of league play. Pre-season tournaments include the European Trophy, Tampere Cup and the Pajulahti Cup. One of the oldest international ice hockey competition for clubs is the Spengler Cup, held every year in Davos, Switzerland, between Christmas and New Year's Day. It was first awarded in 1923 to the Oxford University Ice Hockey Club. The Memorial Cup, a competition for junior-level (age 20 and under) clubs is held annually from a pool of junior championship teams in Canada and the United States.

International club competitions organized by the IIHF include the Continental Cup, the Victoria Cup and the European Women's Champions Cup. The World Junior Club Cup is an annual tournament of junior ice hockey clubs representing each of the top junior leagues.

Other regions

The Australian Ice Hockey League and New Zealand Ice Hockey League are represented by nine and five teams respectively. As of 2012, the two top teams of the previous season from each league compete in the Trans-Tasman Champions League.

Ice hockey in Africa is a small but growing sport; while no African ice hockey playing nation has a domestic national leagues, there are several regional leagues in South Africa.

National team competitions

Ice hockey has been played at the Winter Olympics since 1924 (and was played at the summer games in 1920). Hockey is Canada's national winter sport, and Canadians are extremely passionate about the game. The nation has traditionally done very well at the Olympic games, winning 6 of the first 7 gold medals. However, by 1956 its amateur club teams and national teams could not compete with the teams of government-supported players from the Soviet Union. The USSR won all but two gold medals from 1956 to 1988. The United States won its first gold medal in 1960. On the way to winning the gold medal at the 1980 Lake Placid Olympics, amateur US college players defeated the heavily favoured Soviet squad—an event known as the "Miracle on Ice" in the United States. Restrictions on professional players were fully dropped at the 1988 games in Calgary. NHL agreed to participate ten years later. 1998 Games saw the full participation of players from the NHL, which suspended operations during the Games and has done so in subsequent Games up until 2018. The 2010 games in Vancouver were the first played in an NHL city since the inclusion of NHL players. The 2010 games were the first played on NHL-sized ice rinks, which are narrower than the IIHF standard.

National teams representing the member federations of the IIHF compete annually in the IIHF Ice Hockey World Championships. Teams are selected from the available players by the individual federations, without restriction on amateur or professional status. Since it is held in the spring, the tournament coincides with the annual NHL Stanley Cup playoffs and many of the top players are hence not available to participate in the tournament. Many of the NHL players who do play in the IIHF tournament come from teams eliminated before the playoffs or in the first round, and federations often hold open spots until the tournament to allow for players to join the tournament after their club team is eliminated. For many years, the tournament was an amateur-only tournament, but this restriction was removed, beginning in 1977.

The 1972 Summit Series and 1974 Summit Series, two series pitting the best Canadian and Soviet players without IIHF restrictions were major successes, and established a rivalry between Canada and the USSR. In the spirit of best-versus-best without restrictions on amateur or professional status, the series were followed by five Canada Cup tournaments, played in North America. Two NHL versus USSR series were also held: the 1979 Challenge Cup and Rendez-vous '87. The Canada Cup tournament later became the World Cup of Hockey, played in 1996, 2004 and 2016. The United States won in 1996 and Canada won in 2004 and 2016.

Since the initial women's world championships in 1990, there have been fifteen tournaments.[75] Women's hockey has been played at the Olympics since 1998.[78] The only finals in the women's world championship or Olympics that did not involve both Canada and the United States were the 2006 Winter Olympic final between Canada and Sweden and 2019 World Championship final between the US and Finland.

Other ice hockey tournaments featuring national teams include the World U20 Championship, the World U18 Championships, the World U-17 Hockey Challenge, the World Junior A Challenge, the Ivan Hlinka Memorial Tournament, the World Women's U18 Championships and the 4 Nations Cup. The annual Euro Hockey Tour, an unofficial European championship between the national men's teams of the Czech Republic, Finland, Russia and Sweden have been played since 1996–97.

Attendance records

The attendance record for an ice hockey game was set on December 11, 2010, when the University of Michigan's men's ice hockey team faced cross-state rival Michigan State in an event billed as "The Big Chill at the Big House". The game was played at Michigan's (American) football venue, Michigan Stadium in Ann Arbor, with a capacity of 109,901 as of the 2010 football season. When UM stopped sales to the public on May 6, 2010, with plans to reserve remaining tickets for students, over 100,000 tickets had been sold for the event.[96] Ultimately, a crowd announced by UM as 113,411, the largest in the stadium's history (including football), saw the homestanding Wolverines win 5–0. Guinness World Records, using a count of ticketed fans who actually entered the stadium instead of UM's figure of tickets sold, announced a final figure of 104,173.[97][98]

The record was approached but not broken at the 2014 NHL Winter Classic, which also held at Michigan Stadium, with the Detroit Red Wings as the home team and the Toronto Maple Leafs as the opposing team with an announced crowd of 105,491. The record for a NHL Stanley Cup playoff game is 28,183, set on April 23, 1996, at the Thunderdome during a Tampa Bay Lightning – Philadelphia Flyers game.[99]

Number of registered players by country

Number of registered hockey players, including male, female and junior, provided by the respective countries' federations. Note that this list only includes the 38 of 81 IIHF member countries with more than 1,000 registered players as of October 2019.[100][101]

| Country | Players | % of population |

|---|---|---|

| 621,026 | 1.660% | |

| 567,908 | 0.173% | |

| 121,613 | 1.138% | |

| 112,236 | 0.077% | |

| 64,641 | 1.168% | |

| 55,431 | 0.552% | |

| 27,867 | 0.324% | |

| 21,503 | 0.033% | |

| 21,340 | 0.026% | |

| 18,837 | 0.015% | |

| 11,394 | 0.209% | |

| 10,353 | 0.192% | |

| 8,384 | 0.001% | |

| 8,162 | 0.012% | |

| 7,670 | 0.086% | |

| 7,106 | 0.073% | |

| 7,000 | 0.367% | |

| 6,915 | 0.037% | |

| 5,384 | 0.012% | |

| 5,210 | 0.009% | |

| 5,147 | 0.089% | |

| 4,716 | 0.019% | |

| 4,580 | 0.048% | |

| 3,770 | 0.010% | |

| 3,260 | 0.006% | |

| 3,076 | 0.018% | |

| 2,466 | 0.089% | |

| 2,400 | 0.009% | |

| 2,141 | 0.002% | |

| 1,964 | 0.010% | |

| 1,785 | 0.015% | |

| 1,553 | 0.002% | |

| 1,530 | 0.024% | |

| 1,502 | 0.000% | |

| 1,330 | 0.028% | |

| 1,142 | 0.055% | |

| 1,077 | 0.081% | |

| 1,043 | 0.002% |

Variants

Pond hockey

Pond hockey is a form of ice hockey played generally as pick-up hockey on lakes, ponds and artificial outdoor rinks during the winter. Pond hockey is commonly referred to in hockey circles as shinny. Its rules differ from traditional hockey because there is no hitting and very little shooting, placing a greater emphasis on skating, stickhandling and passing abilities. Since 2002, the World Pond Hockey Championship has been played on Roulston Lake in Plaster Rock, New Brunswick, Canada.[102] Since 2006, the US Pond Hockey Championships have been played in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the Canadian National Pond Hockey Championships have been played in Huntsville, Ontario.

Sledge hockey

Sledge hockey is an adaption of ice hockey designed for players who have a physical disability. Players are seated in sleds and use a specialized hockey stick that also helps the player navigate on the ice. The sport was created in Sweden in the early 1960s, and is played under similar rules to ice hockey.

In popular culture

Ice hockey is the official winter sport of Canada. Ice hockey, partially because of its popularity as a major professional sport, has been a source of inspiration for numerous films, television episodes and songs in North American popular culture.[103][104]

See also

- Glossary of ice hockey

- Ice hockey by country

- Ice hockey at the Olympic Games

- Minor ice hockey

- Hockey

References

Notes

- National Sports of Canada Act

- "The world governing body". IIHF. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- "Koninklijke Nederlandse Hockey Bond". Hockey.nl. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- Including former incarnations of them, such as Czechoslovakia or the Soviet Union.

- "IIHF World Championships: All Medalists: Men". Iihf.com. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- "IIHF World Championships: All Medalists: Women". Iihf.com. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- "Olympic Ice Hockey Tournaments: All Medalists:Women". Iihf.com. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Gidén, Carl; Houda, Patrick; Martel, Jean-Patrice (2014). On the Origin of Hockey.

- {{See The history of Gaelic Football.}}

- Guinness World Records 2015. Guinness World Records. 2014. p. 218. ISBN 9781908843821.

- Rymer, Thomas (1740). Foedera, conventiones, literae, et cujuscumque generis acta publica, inter reges Angliae, et alios quosvis imperatores, reges, pontifices ab anno 1101. Book 3, part 2, p. 79.

- Scott, Sir James Sibbald David (1868). The British Army: Its Origin, Progress, and Equipment. Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Company. p. 86.

- Strype, John (1720). Survey of London. Book 1, pp. 250–251.

- Birley, Derek (1993). Sport and the Making of Britain. Manchester University Press. p. 36. ISBN 9780719037597.

- Joyce, Patrick Weston (1910). English As We Speak It in Ireland.

- "History of Hockey". England Hockey. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- Gidén, Carl; Houda, Patrick (2010). "Stick and Ball Game Timeline" (PDF). Society for International Hockey Research. p. 4.

- "Hockey researchers rag the puck back to 1796 for earliest-known portrait of a player". Canada.com. May 17, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- Kennedy, Brendan (October 4, 2005). "Hockey night in Kingston". The Queen's University Journal. Retrieved June 21, 2006.

- Vaughan, Garth (1999). "Quotes Prove Ice Hockey's Origin". Birthplace of Hockey. Archived from the original on August 6, 2001. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- Dalhousie University (2000). Thomas Raddall Selected Correspondence: An Electronic Edition Archived August 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. From Thomas Raddall to Douglas M. Fisher, January 25, 1954. MS-2-202 41.14.

- "Provincial Sport Act: An Act to Declare Ice Hockey to be the Provincial Sport of Nova Scotia". Nova Scotia Legislature. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- Vennum Jr., Thomas. "The History of Lacrosse". USLacrosse.org. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- "About Shinny USA". Shinny USA. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- Vaughan 1996, p. 23.

- Gidén, Carl; Houda, Patrick (2016). "The Birthplace or Origin of Hockey". Society for International Hockey Research. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- Gidén, Carl; Houda, Patrick; Martel, Jean-Patrice (2014). On the Origin of Hockey. Hockey Origin Publishing. ISBN 9780993799808.

- "IIHF to recognize Montreal's Victoria Rink as birthplace of hockey". IIHF. July 2, 2002. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- "Victoria Rink". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. March 3, 1875.

- "Hockey on the ice". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. February 7, 1876.

- Fyffe, Iain (2014). On His Own Side of the Puck. pp. 50–55.