Copper mining in the United States

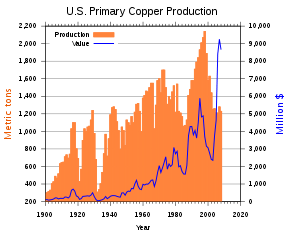

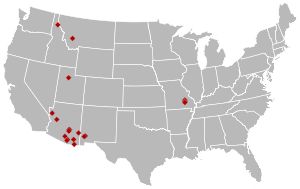

Copper mining in the United States has been a major industry since the rise of the northern Michigan copper district in the 1840s. In 2017 the United States produced 1.27 million metric tonnes of copper, worth $8 billion, making it the world's fourth largest copper producer, after Chile, China, and Peru. Copper was produced from 23 mines in the US. Top copper producing states in 2014 were (in descending order) Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, Nevada, and Montana. Minor production also came from Idaho, and Missouri. As of 2014, the US had 45 million tonnes of known remaining reserves of copper, the fifth largest known copper reserves in the world, after Chile, Australia, Peru, and Mexico.[1]

Copper in the US is used mainly in construction (43%) and electric equipment (19%). In 2014, the nation produced 69% of the copper it used, relying on imports from Chile, Canada, Peru, and Mexico for the remaining 31%.[1]

Copper mining activity increased in the early 2000s because of increased price: the price increased from an average of $0.76 per pound for the year 2002, to $3.02 per pound for 2007.[2]

A number of byproducts are recovered from American copper mining. In 2013, American copper mining produced 28,500 metric tons of molybdenum, worth about $700–$800 million, which was 47% of total US production.[3] In 2014, copper mining produced about 15 metric tons of gold, worth $600 million, which represented 7% of US gold production.[4] Other byproducts of the copper extraction process included silver, and minor amounts of rhenium and platinum-group metals. Sulfuric acid is recovered at copper smelters.[5]

Ore grades

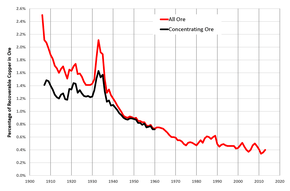

From the start of copper mining in the Michigan copper district, ore has been divided into two classes. The rock with higher copper content was smelter ore, also called direct shipping ore, and required no treatment before going to the smelter. The rock with less copper was called milling ore, or concentrating ore, and required crushing and separation of ore minerals from the waste rock to produce copper concentrate, which was sent to the smelter.

Because metallic minerals have higher specific gravities than most gangue (waste) minerals, concentrating the milling ore was done in various gravity classifiers. The early Michigan copper mines used buddles. Later copper mining used improved gravity-classification machinery, including jigs, vanners, and Wilfley tables.

A revolutionary development in American copper mining took place when mining engineer Daniel Cowan Jackling conceived of mining the huge but low-grade copper ore body at Bingham Canyon, Utah, using steam shovels in a big open pit. Steam shovels had previously been used in the iron mines of the Mesabi Range, in Minnesota, but had not been used in copper mining. Jackling incorporated the Utah Copper Company in 1903, and in 1906 began excavating. From the start, the Bingham Canyon Mine was one of the leading copper-producing mines in the world, and returned a good profit mining ore with less than two percent copper.[6] Mining by open-pit model using large-scale mechanization was copied by other US mines, in Ely, Nevada (1908), Santa Rita, New Mexico (1910), and Ajo, Arizona (1917). The entire output of these mines was low-grade milling ore. The open-pit mining of porphyry copper deposits was adopted worldwide.

In the 1910s and 1920s, copper mills adopted the froth flotation method, which had been developed in Australia. Whereas the old gravity methods of concentration, using jigs and Wilfley tables recovered 60 to 80 percent of the copper in the ore, froth flotation recovered 90 to 95 percent.[7] The Bingham Canyon mill installed froth flotation in 1918.

Large-scale mining of low-grade orebodies became predominant, and the amount of direct-shipping ore mined fell drastically in the first half of the 20th century, and by 1960, the contribution of direct-shipping ore was insignificant. Improvements in low-cost mining and ore processing allowed the average ore grade of milling ore to decline.

Smelters

There are three operating copper smelters in the United States.[8]

- Grupo Mexico, Hayden, Arizona [9]

- Rio Tinto, Garfield, Utah [10]

- Freeport McMoRan, Miami, Arizona [11]

The United States is a net exporter of copper ore and copper concentrate. In 2015, out of 1.25 million metric tons of recoverable copper metal extracted from mines, 320,000 tons of copper were exported in the form of ore and concentrate, to be smelted and refined elsewhere.

By state

Alabama

The Stone Hill mine (also known as the Woods mine) was discovered in 1874, and worked 1874 to 1879, and 1896 to 1899. Production was hampered by poor transportation. The ore is massive and disseminated sulfides in hornblende schist of Precambrian or Paleozoic age. Principal ore minerals are chalcopyrite and sphalerite, which occur with pyrrhotite, pyrite, and quartz. Two other copper prospects, the Johnston prospect and the Smith prospect, are nearby, but it is not known that any copper was produced from them.[12]

Alaska

Alaska is not currently a significant copper producer.

Russian explorers discovered copper on the Kasaan Peninsula of Prince of Wales Island in southeastern Alaska about 1865. Mining began in the period 1895–1900, and continued until shortly after World War I. Copper is present as chalcopyrite, occurring with magnetite, pyrite, garnet, epidote, diopside, and hornblende, in replacement deposits in greenstone. Gold and silver were recovered as byproducts.[13]

Copper was discovered at Prince William Sound in 1897. Deposits were associated with pillow basalts alterered to greenstone. The basalts are interbedded with slate and greywacke, faulted, and intruded by granitic rocks. The principal mines were the Beatson-Bonanza mine at Latouche and the Ellamar mine, which accounted for 96% of the copper produced. Other mines were the Midas mine near Valdez, the Threeman mine, and the Fidalgo-Alaska mine at Port Fidalgo, Alaska. Mining began in 1900, and continued until 1930. Total production was 96,000 tonnes of copper.[14]

Historically, the largest copper mining district in Alaska was the Nizina district, the principal mines of which (Erie mine, Jumbo mine, Bonanza mine, Mother Lode mine, and Green Butte mine) were at Kennecott, Alaska, four miles north of McCarthy. The copper is present as chalcocite in veins and irregular replacements in the Triassic Chitistone Limestone. Some silver was also produced as a byproduct.[15] The mine at Kennecott gave rise to Kennecott Copper Corporation, which outlasted the mine, and is still a major mining company. The deposit was discovered in 1900, and once a railroad connection was built, the mine operated from 1911 to 1938, after which Kennecott became a ghost town. The town is now a National Historic Landmark.

The Pebble Mine is a proposed copper-gold-molybdenum mine. The deposit is a large porphyry copper-gold-molybdenum deposit, and if developed would be a major producer of those metals.

Arizona

Arizona has been a major copper producer since the 19th century. In 2006 Arizona was the leading copper-producing state in the US, producing a record $5 billion worth of copper.[16]

Over 60% of the newly mined copper in the U.S. comes from Arizona. When copper traded for an average of $3.30/pound, copper production generated nearly $5 billion for Arizona's economy in 2006 and $5.5 billion in 2007.

The first mineral to be mined in Arizona was, as in many other regions, gold. Silver was also prominent, in the cities of Tubac and Superior. However, Arizona would most prominently be known for its copper, which would eventually become known as one of Arizona's Five C's or resources.[17]

The first copper strike by an Anglo was by Henry Clifton, in the area now known as Clifton, in 1864. No claim was staked there because of threat of Indian attack. In 1870, Robert Metcalf staked a claim there, then sold controlling interest to Henry and Charles Lesinsky. They later formed the Longfellow Copper Mining Co. in Las Cruces, New Mexico. They set up camp and called it Clifton. Clifton later became one of the largest copper mining communities of Arizona.

This new use of copper resulted in the boom of one of Arizona's greatest resources. By 1910 Arizona produced more copper than any other state in the nation. It would eventually fuel many of its political struggles as well. The Bisbee and Jerome Deportations in 1917 represent how factory workers and factory owners were pitted against each other.[18]

At Mule Canyon, south of Tombstone, Arizona, in 1877, a soldier chasing Apache Indians found copper at Bisbee. The Copper Queen Mine and neighboring Atlanta Claim became the Warren District. With the great contribution of the Warren District, Arizona led the nation and still leads it in copper production.

The United Verde copper mine at Jerome, Arizona, was financed by eastern capitalists. However, the rich surface ore soon played out. W. A. Clark, who had obtained his fortune at Butte, purchased 99% of the stock of the United Verde Mine. Ultimately it yielded copper, silver, and gold totaling $410,000,000. W. A. Clark was the owner of the richest, individually owned copper mine in the world. After the mines closed Jerome was reborn as an artist community.

12 active copper mines in Arizona directly employ nearly 10,000 workers, not including contractors and sub-contractors. Half of Arizona's copper is mined in Morenci. An additional nine copper mines are expected to begin production in the coming years. The Resolution Copper Project, near Superior, is expected to provide 25% of the U.S. demand for copper after it begins production.[19]

California

Copper was first discovered in California in 1840, in Los Angeles County. The mine, at Soledad, produced a small amount of copper in 1854.[20]

The Napoleon mine at Copperopolis in Calaveras County opened in 1860, and was so productive that it ignited a boom in other copper-mining properties from 1862 to 1866. The boom stimulated development of copper mines along the Foothill copper belt, a 250-mile long zone of copper deposits in the Sierra Nevada foothills, running from Butte County in the northwest to Fresno County in the southeast. Production nearly ceased after 1868 when the shallow oxidized ore was exhausted, and the deeper sulfide ores were found to be poorer in gold and silver.[21] The Foothills belt yielded 91 thousand tonnes of copper and 23 thousand tonnes of zinc.

Most California copper production came from the West Shasta district in northern California. Gold prospectors discovered the copper deposits of Shasta County in 1848, but no metal was produced until 1879, when some silver was produced from the Iron Mountain Mine. The copper was in massive sulfide deposits in the Devonian Balaklala Rhyolite. The principal mines were the Iron Mountain Mine, Mammoth Mine, and the Balaklala Mine. Copper production began in 1894, and continued off-and-on until 1976. Total production was 320 thousand tonnes of copper, 93 million pounds of zinc, 36 million troy ounces of silver, and 520,000 ounces of gold. The district also produced pyrite for sulfuric acid.[22]

The Island Mountain mine in Trinity County operated from 1915 to 1930, and produced 4100 tonnes of copper, 140,000 ounces of silver, and 8,600 ounces of gold. The orebody is a massive sulfide deposit of pyrite, chalcopyrite, and pyrrhotite along a shear zone in the Franciscan Formation.[23]

At the northern end of the Sierra Nevada, in Plumas County, the Walker, Engels, and Superior mines together produced more than 140 thousand tons of copper.[24] The Engels Mine produced 117 million pounds of copper ore and was the largest copper mine in California.

The Pine Creek mine near Bishop in Inyo County produces some copper as a byproduct of tungsten mining.

Connecticut

Connecticut is home to the first successful copper mining by Europeans in what is now the United States.[25] A copper deposit was discovered in the present town of East Granby, Connecticut in 1705, and German metallurgists from Hanover were imported to reduce the ore to copper metal.[26] The mine was shut down in 1725, and the property served as a prison from 1773 to 1897.[27]

Maine

Copper mines operated in Hancock County near Blue Hill and Sullivan, from 1877 to 1884.[28]

The Harborside mine, near Brooksville mined copper and zinc from an open pit from 1968 to 1972.

The underground Black Hawk mine near Blue Hill produced copper, zinc, and lead from 1972 to 1977.[29]

Maryland

Copper mines operated in Maryland from colonial times until the 1850s, in three mining districts. The most productive was in Frederick County, in a belt of chalcopyrite ore in schist and limestone stretching from New London to Libertytown. The most productive mine was the Dolly Hyde mine. Another district contains chalcopyrite, chalcocite, and bornite, in a fault zone that runs 25 miles in slate from Sykesville to Finksburg in Carroll County. The Bare Hills district in northwest Baltimore County contained a copper-bearing vein in hornblende gneiss.[30]

Michigan

Native Americans mined copper from small pits on the Keweenaw Peninsula of northern Michigan as early as 3000 BC.[31] In the American era, the first successful copper mine, the Cliff mine, began operations in 1845, and many others quickly followed. The last major copper mine in Michigan, the White Pine mine, shut down in 1995, after unsuccessfully applying for a permit to convert the underground mine to an in-situ leaching operation.

Minnesota

Polymet Mining Corp. has proposed a large open-pit copper-nickel mine of its Northmet orebody in St. Louis County, Minnesota. The company has applied with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and with the US Corps of Engineers for the required permits. Present plans call for the mine to produce 72 million pounds (33 thousand tonnes) of copper annually, along with nickel, cobalt, platinum, palladium, and gold.[32][33]

Franconia Minerals Corp. is exploring three copper-nickel platinum deposits in St. Louis and Lake Counties. Like the Northmet deposit, the deposits are in the Duluth Complex.[34] [35]

Missouri

Missouri has produced small amounts of copper from Franklin, Madison, and other counties since 1837. A copper mine started in 1863 near Cornwall in Madison County.[36]

Copper is recovered as a byproduct of lead mining in the Lead Belt of southeastern Missouri.

Montana

In 2006, Montana was the fourth-largest copper-producing state in the country.

Butte, Montana was once the nation's most prolific copper-mining district. Miners first came to Butte in 1864 to mine placer gold. Hard rock silver mining began in 1874, then rich copper veins were discovered in 1882. The district quickly switched from silver to copper, and by 1887, Butte was the leading copper-producing district in the United States. The Anaconda Copper Mine was the world's most productive copper mine from 1892 through 1903, and intermittently for years thereafter.[37] Open-pit mining began at the Berkeley Pit in 1955; the Berkeley Pit has been inactive for years, and continues to fill with acidic water. Through 1964, Butte produced 7.3 million tonnes of copper, 2.2 million tonnes of zinc, 1.7 million tonnes of manganese, 380 thousand tonnes of lead, 645 million troy ounces of silver, and 2.5 million ounces of gold.[38] The only remaining active copper mine at Butte is the Continental pit, operated by Montana Resources LLP.

Some copper is also produced by Troy unit silver mine in the northwest corner of the state, and by two platinum mines in the Stillwater igneous complex: the Stillwater mine and the East Boulder project.[39]

Nevada

The first commercial copper mining district in Nevada was at Yerington in Lyon County. The Ludwig Mine opened in 1865, but the district produced only modest amounts of copper until a railroad was built to the district in 1911, and a smelter built in 1912 at nearby Thompson. The Anaconda Copper Mine produced from an open pit from 1918 to 1978. The copper ore bodies are contact metamorphic replacement deposits in limestone. Production through 1921 was 39 thousand tonnes of copper.[40]

The largest copper producer in Nevada has been the Ely district (also called the Robinson district) in White Pine County. A Native American showed mineralization to prospectors in 1867, and the district started in a small way as a lode gold producer. A railroad link in 1906 made it economically possible to start large scale open pit mining of the large porphyry copper deposits, and the first copper was produced in 1908.[41] Mining was halted in recent years due to low copper prices, but the open pit was reopened in 2004 by Quadra Mining Ltd. In 2007, the mine produced 121 million pounds (55 thousand tonnes) of copper, plus byproduct molybdenum.

Newmont's Phoenix mine in Lander County produced 6.2 million pounds (2800 tonnes) of copper in 2007, as a byproduct of gold mining.[42]

New Jersey

New Jersey was the site of one of the first attempts to mine copper in what is now the United States. Copper ore was discovered about 1712 in what is now North Arlington, and the Schuyler Copper Mine extracted ore and shipped it in casks to the Netherlands. The success of the Schuyler mine led to more prospecting and discovery of more deposits.[43]

In the 1750s, colonists tried to mine copper at the Pahaquarry Copper Mine in Warren County.[44] The copper occurs as chalcocite, bornite, covellite, cuprite, and malachite, in quartzite of the Silurian High Falls Formation.[45]

New Mexico

The Santa Rita mine in southwest New Mexico was the first copper mine in what is now the western United States. Spaniards began mining copper there about 1800. The district still produces copper, from the large Chino Mine open pit.

Native Americans had mined turquoise associated with the copper deposits at present-day Tyrone in Grant County, New Mexico. Modern mining followed the discovery of turquoise and copper by American prospectors in 1870. The first copper was shipped from the Tyrone district in 1879.[46]

Some copper has been produced from three deposits in sandstone of the Triassic Chinle Formation in the Nacimiento Mountains near Cuba, New Mexico. The copper is present as sulfides (most commonly chalcocite) and malachite associated with organic material; some native silver is also present.[47]

New Mexico is currently the nation's number-three copper-producing state. Copper is produced from two large open-pit porphyry copper operations in Grant County: the Chino Mine and the Tyrone mine. Both mines are owned and operated by Freeport-McMoRan. In 2007, the two mines produced 249 million pounds (113 thousand tonnes) of copper, as well as 13 thousand ounces of gold and 209 thousand ounces of silver.[48]

New York

A copper mine operated at Canton, St. Lawrence County in the 19th century.[49]

North Carolina

Copper was discovered at the Ore Knob deposit in the northwest part of the state in the early 1850s, and mining began in 1855. The ore is massive sulfide and disseminated ore in mica schist and gneiss, and amphibole schist and gneiss. The principal ore mineral is chalcopyrite, which occurs with pyrrhotite and pyrite, The mine operated until 1883, then worked sporadically until large-scale mining began in 1957. The mine closed for good in 1962. Total production was 31,000 tonnes of copper, 9,400 ounces of gold, and 145,000 ounces of silver.[50]

Oklahoma

Copper was mined at Creta from 1965 to about 1975. The ore 2% to 4.5% copper as chalcocite replacement grains in an 8-inch (20 cm) thick bed of grey shale in the Permian Flowerpot Shale. The ore also carried some silver, as stromeyerite.[51]

Copper and silver occur in a sandstone roll-front-type deposit in the Wellington sandstone of Permian age at Paoli, Garvin County, Oklahoma. About 1900, several wagon loads of ore were shipped from the deposit.[52]

Oregon

The leading copper-mining district in Oregon was the Homestead district in Baker County, which produced 6400 tonnes of copper, 35,000 ounces of gold, and 256,000 ounces of silver. The most important mine was the Iron Dyke.[53]

The Waldo-Takilma district in Josephine County produced 3200 tonnes of copper. Large mines included the Waldo Mine and the Queen of Bronze Mine.

The Keating district in Baker County produced 450 tonnes of copper.

Pennsylvania

In 1724 Pennsylvania colonial governor William Keith made the first attempt to mine copper in Pennsylvania. His mine, in York County, failed within a short time.

By 1732 the Gap mine in Lancaster County was operating, owned by shareholders including Gouverneur Morris and Thomas Penn. The mine shut down due to water problems about 1755.[54] The mine reopened as a nickel mine about 1850, and produced some byproduct copper along with the nickel until it shut down in 1893.[55]

Tennessee

The Copper Basin, located in the extreme southeastern corner of Tennessee in Polk County, was the center of a major copper-mining district from 1847 into the 1970s. The district also produced iron, sulfur and zinc as byproducts.[56] The copper was discovered in 1843 by a prospector, presumably panning for gold, who found nuggets of native copper. The first shipment of copper ore was taken out on muleback in made in 1847. More than 30 mining companies were incorporated between 1852 and 1855 to mine copper at Ducktown. Development was speeded by a road built in 1853 connecting the area with Cleveland, Tennessee. The first smelter was built in the Ducktown district in 1854. Mining ceased when Union troops destroyed the copper refinery and mill at Cleveland, Tennessee in 1863. Mining resumed in 1866, and continued until 1878, when the mines had exhausted the shallow high-grade copper ores.

In 1889, the Ducktown Sulphur, Copper, Gold and Iron Company bought the properties, and began producing copper and iron from the deeper high-sulfide ores, which previous companies were unable to work successfully. The ores were treated by open roasting in which the ore was piled in large stacks with alternating layers of wood, and burned. The method released large quantities of sulfur dioxide, which killed much of the vegetation in the immediate area. Open roasting was replaced by pyrite smelting in 1904, and the smelters began recovering the most of the sulfur in the form of sulfuric acid rather than releasing it to the atmosphere. Froth flotation was added in the 1920s.

The Burra Burra Mine in Ducktown is now home to a museum dedicated to the interpretation of the region's copper mining history.

Texas

Texas has never been a major copper-mining state. Small amounts of copper were mined from Permian redbeds in Archer and Foard counties of north-central Texas in the 1860s and 1870s. Copper was produced in connection with silver mining in Culberson County in west Texas from 1885 to 1952.[57]

Utah

In 2006, Utah was the nation's number two producer of copper.

The Bingham Canyon Mine southwest of Salt Lake City has been one of the world's largest copper producers for more than 100 years. The mine, owned and operated by Kennecott Utah Copper (a division of Rio Tinto Group), is a large open pit in a porphyry copper deposit. (The Bingham Canyon Mine and the Chuquicamata copper mine in Chile each claim to be the largest open-pit mine in the world.) It continues to be a major source not only of copper, but also of molybdenum, gold, and silver. The value of metals produced in the year 2006 alone was $1.8 billion.[58]

Constellation Copper's Lisbon Valley copper mine in San Juan County, southeastern Utah began mining in 2005, and produced its first copper in 2006.[59] The copper deposit is in sandstones of the Dakota Sandstone and Burro Canyon Formation. The primary copper mineral is chalcocite, which is thought to have been deposited from solutions ascending through the Lisbon Valley Fault. Above the water table, chalcocite has been oxidized to malachite, azurite, tenorite, and cuprite.[60] On November 30, 2007, Constellation announced that it would stop mining in 2008, because of unexpectedly low copper recovery. The company will continue to recover copper by heap-leaching already-mined ore as long as profitable.[61][62]

Constellation officially declared bankruptcy and is currently insolvent, but copper mining efforts were resumed in August 2009 under new management with the help of financing from Renewal Capital, a subsidiary of PartnerRe, and has been producing approximately 35,000 pounds of copper a day since the restart. Mining occurs solely in one mid-sized open pit named the Centennial pit, and the primary ores are malachite, azurite, and chalcocite. The mine employs approximately 140 people as of February 2012.

CS Mining purchased the assets of the bankrupt Western Utah Copper Company/Copper King Mining Corporation in 2011 and has applied for the required permits to restart the mining at various sites previously held by WUCC. After receipt of the permits, mining and milling activities are expected to start in the second half of 2012 with open-pit mining and flotation mill processing near Milford. At the time the assets were acquired by CS, the measured, indicated and inferred resources were approximately 600 million pounds of copper; plus gold, silver, and magnetite. [63]

Vermont

A number of copper mines operated in Orange County from 1809 to 1958.[64] At least five copper mines operated along a belt 20 miles long and oriented NNE-SSW. Until the opening of the Michigan copper district in 1844, Vermont was the leading copper-producing state. The ore was chalcopyrite with pyrite and pyrrhotite in sericite schist host rock.[65]

The Elizabeth deposit was discovered in 1793 and started mining in 1809 as the first copper mine in the state; it was also the last copper mine to operate in the state when it closed in 1958.[64][66] The Elizabeth mine is now a federal Superfund site due to acid mine drainage.[67]

Virginia

The Virginian mining district in Halifax and Charlotte Counties in southern Virginia produced about 750,000 pounds of copper from numerous mines. Copper-bearing quartz veins occur in greenstone schist along a narrow belt stretching four miles NNE-SSW from Keysville on the north to Virgilina on the North Carolina border. The Barnes mine is reported to have produced some copper in the early 18th century, but the major productive era for the district was the late 19th century to 1917.[68]

The Toncrae deposit near Floyd was mined for iron (from the gossan) from about 1790–1850. Copper was mined from 1854–1855, 1905–1908, and 1938–1947. The deposit is a massive sulfide, composed mainly of pyrrhotite and magnetite. The main copper ore minerals are chalcocite and covellite.[69][70]

Washington

The Tubal Cain mine on the Olympic Peninsula operated from 1902 to 1906.

The Holden mine, in Chelan County, operated from 1938 to 1957. The townsite is now used as a Lutheran retreat center and is open to the public. The process of cleaning up the remains of the old mine is ongoing.

The Chewelah district in Stevens County produced 1.7 million troy ounces (53 tonnes) of silver and 5,000 metric tons of copper from quartz-carbonate veins. Chalcopyrite is the principal ore mineral. The deposits are hosted in shear zones in argillite of the Precambrian Belt Supergroup.[71]

Wisconsin

Copper was discovered one mile northeast of Mineral Point in Iowa County of southwest Wisconsin in 1837 or 1838. The deposit was mined until 1842, then intermittently through 1875, producing an estimated 680 tonnes of copper.[72]

Copper was discovered in 1843 at what became known as the Copper Creek mine near Mount Sterling in Crawford County, southwest Wisconsin. About 5500 pounds (2.5 tonnes) of copper were produced from the deposit between 1843 and 1852.[73] The Plum Creek copper mine, also in Crawford County, was discovered near Wauzeka in the 1850s, and mined in 1860 and 1861. Both the Copper Creek and Plum Creek deposits are in limestone.[74]

Douglas County, in the northwest corner of the state, was heavily prospected in the 19th century for native copper deposits in Keweenawan-series rocks, similar to deposits found in Keweenawan rocks in Michigan. A number of mines were started, but none proved profitable.[75]

The copper deposit of the Flambeau mine was discovered in 1969 1.5 miles south of Ladysmith in Rusk County, and produced from an open pit from 1993 to 1997. Total production was 160 thousand tonnes of copper, 3.3 million ounces (100 tonnes) of silver, and 330 thousand ounces (10 tonnes) of gold. Kennecott reclaimed and revegetated the site to specifications of a state-approved reclamation plan, finishing in 1999.[76] The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources continues long-term vegetation and groundwater monitoring of the site to assure that the reclamation was done successfully.[77]

Wyoming

The Encampment district in Carbon County produced 24 million pounds of copper in a brief spurt of activity from 1899 to 1908.[78]

Copper mines were opened near Hartville in Goshen County in 1882. The mines produced until about 1899, and again during World War I.[79]

Although no copper mines have operated in Wyoming in recent years, there are several properties with large-tonnage copper-silver porphyries (Tertiary) in the Absaroka Mountains east of Yellowstone, stratabound copper-silver-zinc massive sulfides (Triassic-Jurassic) in the Lake Alice district in the overthrust belt of Western Wyoming, several volcanogenic massive sulfide (copper, lead, zinc, silver) deposits in the Encampment district, a potentially major stratabound copper-gold paleoplacer (Proterozoic) at the Ferris-Haggarty property in the Sierra Madre, a Proterozoic copper-gold porphyry at the Copper King property in the Laramie Range, and other properties of interest (Hausel, 1997).

See also

- Lists of copper mines in the United States

- Spring Creek Dam, a dam built to contain acid mine drainage from copper mining.

Footnotes

- Mineral Commodity Summary - U.S. Geological Survey - January 2018

- D.R. Wilburn, "Exploration review," Mining Engineering, May 2008, p.47.

- Molybdenum US Geological Survey, Minerals Yearbook 2013.

- Gold US Geological Survey, Commodity Updates, 2015

- US Geological Survey, Sulfur, Minerals Yearbook, 2012.

- Horace J. Stevens, The Copper Handbook, v8 (Houghton, Mich: Horace Stevens, 1908) 1377–1381.

- George J. Young, Elements of Mining, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1946) 3.

- World copper smelters, US Geological Survey, published 2002, accessed 21 June 2016.

- Archived 2018-02-04 at the Wayback Machine, Grupo Mexico, accessed 18 July 2018.

- Archived 2018-03-16 at the Wayback Machine, Rio Tinto, published 28 February 2017, accessed 18 July 2018.

- , Freeport McMoRan, published 2 April 2017, accessed 18 July 2018.

- Gilbert H. Espenshade (1963) Geology of some copper deposits in North Carolina, Virginia, and Alabama, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 1142-I, p.I42-I46.

- L.A. Warner, E.N. Goddard, and others (1961) Iron and copper deposits of Kasaan Peninsula, Prince of Wales Island, Southeastern Alaska, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 1090.

- Fred H. Moffit and Robert E. Fellows (1950) Copper Deposits of the Prince William Sound District, Alaska, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 963-B.

- Don J. Miller (1946) Copper Deposits of the Nizina District, Alaska, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 947-F.

- Arizona Mining Association: Copper, the star of Arizona Archived 2012-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 6 April 2009.

- COPPER: THE FOUNDATION OF AMERICA'S 48TH STATE

- Bisbee, Arizona library

- Arizona Geology: Blogspot

- Horace J. Stevens (1909) The Copper Handbook, v.8, Houghton, Mich.: Horace Stevens, p.176.

- A. Robert Kinkel and Arthur R. Kinkel Jr. (1966) Copper, in Mineral Resources of California, California Division of Mines and Geology, Bulletin 191, p.141-144.

- Bruce Geller, West Shasta, California, Mining Record (Denver), 27 July 1983, p.4.

- Fenelon F. Davis (1966) Economic Mineral Deposits in the Coast Ranges, in Geology of Northern California, California Division of Mines and Geology, Bulletin 190, p.320.

- William B. Clark (1966) Economic mineral deposits of the Sierra Nevada, in Geology of Northern California, California Division of Mines and Geology, Bulletin 190, p.209.

- The Higley Copper and Copper Mining in Connecticut - Geology.com

- James A. Mulholland (1981) A History of Metals in Colonial America, University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, p.43-45.

- New Gate Prison Archived 2007-06-13 at the Wayback Machine - East Granby Historical Society

- Horace J. Stevens (1909) The Copper Handbook, v.8, Houghton, Mich.: Horace Stevens, p.181.

- Mine History - State of Maine

- Horace J. Stevens (1909) The Copper Handbook, v.8, Houghton, Mich.: Horace Stevens, p.181-182

- James A. Mulholland (1981) A History of Metals in Colonial America, University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, p.41-42.

- "Northmet project ahead of the pack in Minnesota polymetallic resource rush," Engineering & Mining Journal, January /February 2008, p.4-6.

- "New Minnesota mining projects remain on track despite economy," Mining Engineering, July 2009, p.31.

- William R. Yernberg, "New projects highlight Minnesota's mining industry," Mining Engineering, July 2008, p.38.

- "New Minnesota mining projects remain on track despite economy," Mining Engineering, July 2009, p.31-32.

- Horace J. Stevens (1909) The Copper Handbook, v.8, Houghton, Mich.: Horace Stevens, p.191.

- Horace J. Stevens (1908) The Copper Handbook, v.8, Houghton, Mich.: Horace Stevens, p.1457, 1466

- Charles Meyer and others (1968) Ore deposits at Butte, Montana, in Ore Deposits of the United States, 1933–1967, New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers, p.1376.

- R. McCulloch, Montana, Mining Engineering, May 2007, p.93-95.

- Francis Church Lincoln (1923) Mining Districts and Mineral Resources of Nevada, reprinted 1982, Las Vegas: Nevada Publications, p.133-134.

- Francis Church Lincoln (1923) Mining Districts and Mineral Resources of Nevada, reprinted 1982, Las Vegas: Nevada Publications, p.245-246.

- J.L. Muntean and D.A. Davis, "Nevada," Mining Engineering, May 2008, p.105.

- James A. Mulholland (1981) A History of Metals in Colonial America, University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, p.39.

- Kraft, Herbert C. (1996). The Dutch, the Indians and the Quest for Copper: Pahaquarry and the Old Mine Road. West Orange, New Jersey: Seton Hall University Museum. ISBN 978-0-935137-02-6.

- H.R. Cornwall (1943) Pahaquarry Copper Mine, Pahaquarry, N. J., US Geological Survey, Open-File Report 45-9.

- Elliot Gillerman (1964) Mineral deposits of western Grant County, New Mexico, New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources, Bulletin 83, p.42.

- Lee A. Woodward and others, Strata-bound copper deposits in Triassic sandstone of Sierra Nacimiento, New Mexico, Economic Geology, January -February 1974, p.108-120.

- S. A. Lucas Kamat, New Mexico, Mining Engineering, May 2008, p.109-111.

- Horace J. Stevens (1909) The Copper Handbook, v.8, Houghton, Mich.: Horace Stevens, p.198.

- Arthur R. Kinkel Jr. (1967) The Ore Knob Copper Deposit North Carolina, and Other Massive Sulfide Deposits of the Appalachians, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 558.

- Hagni, Richard D., "The Replacement Character of Copper-Silver Mineralization in the Permian Flowerpot Shale and Wellington Sandstone Formations of Oklahoma" Archived 2016-03-10 at the Wayback Machine - Department of Geology and Geophysics, Univ of Missouri-Rolla - Geological Society of America - March 24, 2003

- P.N. Shockey and others, (1974) Copper-silver solution fronts at Paoli, Oklahoma, Economic Geology, v.69, n.2, p.266-268.

- R.G. Bowen (1969), Copper, lead, and zinc, in Mineral and Water Resources of Oregon, Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, Bulletin 64, p.123.

- James A. Mullholland (1981) A History of Metals in Colonial America, University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, ISBN 0-8173-0053-8, p.49-50.

- Horace J. Stevens (1908) Copper Handbook, v.8, Houghton, Michigan: Horace Stevens, p.200.

- Maurice Magee (1968) Geology and ore deposits of the Ducktown district, Tennessee, in Ore Deposits of the United States 1933–1967, New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers, p.207-241.

- John Q. Anderson and Diana J. Kleiner: Copper Production from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved December 24, 2008.

- R.L. Bon and K.A. Krahulec, "Utah", Mining Engineering, May 2007, p.116-120.

- Lisbon Valley Copper Mine: Utah, United States Archived 2007-07-28 at the Wayback Machine - Constellation Copper Corp.

- "Constellation Copper Corporation: Resource Estimate Centennial Deposit Archived 2007-08-20 at the Wayback Machine - SRK Consulting - February 2006 - (Adobe Acrobat *.PDF document)

- "Constellation stops mining at Lisbon Valley Copper," Engineering & Mining Journal, December 2007, p.10.

- Peterson, Jodi. "Death of a mine" High Country News, February 18, 2008

- Utah History to Go: Copper mining, the king of the Oquirrh Mountains

- Johnsson, Johnny. "South Strafford’s Elizabeth Copper Mine: The Tyson Years, 1880–1902" - Vermont History - Vermont Historical Society - Vol. 70, Nos. 3 & 4; Summer/Fall 2002 - pp. 130–152. - (Adobe Acrobat *.PDF document)

- Stevens, Horace J. (1908). The Copper Handbook, v.8, Houghton, Mich.: Horace Stevens, p.17.

- The Legacy of the Elizabeth Mine Archived 2007-07-07 at the Wayback Machine - The Center for Environmental Health Sciences at Dartmouth - (c/o Dartmouth College)

- "Elizabeth Mine Superfund Site Cleanup Alternatives Fact Sheet" Archived 2008-05-12 at the Wayback Machine - EPA - (c/o Dartmouth College) - June 2006 - (Adobe Acrobat *.PDF document)

- Virginia Minerals, Volume 22-Number 3 Archived 2007-08-04 at the Wayback Machine - Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy - August 1976 - (Adobe Acrobat *.PDF document)

- Gilbert H. Espenshade (1963) Geology of some copper deposits in North Carolina, Virginia, and Alabama, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 1142-I, p.I36-I41.

- "Virginia Division of Geology and Mineral Resources: Copper". Archived from the original on 2008-08-27. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- Allen V. Heyl and others, Silver, in United States Mineral Resources, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 820, p.594-595

- Geology of Wisconsin, v.2, (1877) Wisconsin Geological Survey, p.741.

- David D. Owen, Report of a Geological Survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota, (Phila.: Lippencott, Grambo, 1852) 53–55

- Geology of Wisconsin, v.4, (1882) Wisconsin Geological Survey, p.69-71.

- Roland Duer Irving (1883) The copper-bearing rocks of Lake Superior, US Geological Survey, Monograph 5, p.251.

- Flambeau Reclaimed - Flambeau Mining Company

- "Reclaimed Flambeau Mine" Archived 2007-08-10 at the Wayback Machine - Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources - May 01 2006

- Frank W. Osterwald and others (1966) Mineral Resources of Wyoming, Geological Survey of Wyoming, Bulletin 50, p.37.

- W. Dan Hausel (1994) Mining history of Wyoming's gold, copper, iron, and diamond resources, in Mining History Association 1994 Annual, p.41.

Further reading

- Matthew L. Basso, Meet Joe Copper: Masculinity and Race on Montana's World War II Home Front. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

- Kent A. Curtis, Gambling on Ore: The Nature of Metal Mining in the United States, 1860–1910. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2013.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Copper mining in the United States. |

![]()