Red Clay State Park

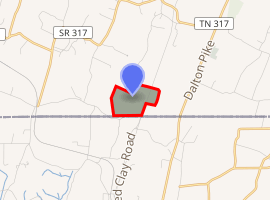

Red Clay State Historic Park is a state park located in southern Bradley County, Tennessee established in 1979. The park is also listed as an interpretive center along the Cherokee Trail of Tears. It encompasses 263 acres (1.06 km2) of land and is located just above the Tennessee-Georgia stateline.

| Red Clay State Historic Park | |

|---|---|

Eternal Flame of the Cherokee Nation | |

| |

| Type | Tennessee State Park |

| Location | Bradley County, Tennessee |

| Area | 263 acres (1.06 km2) |

| Open | year round |

Red Clay Council Ground | |

| |

| Nearest city | Cleveland, Tennessee |

| Area | 150 acres (61 ha) |

| Website | Red Clay State Park |

| NRHP reference No. | 72001229[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 14, 1972 |

The park was the site of the last seat of the Cherokee national government before the 1838 enforcement of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 by the U.S. military, which resulted in most of the Cherokee people in the area being forced to emigrate West. Eleven general councils were held at the site between 1832 and 1837.[2]

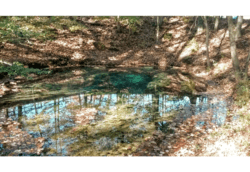

Before the site was a government council site, it was used for many different Cherokee rituals because of its famous spring named the Blue Hole Spring.

History

Long before the arrival of the first European settlers, the area was part of the Cherokee Nation. After the Hiwassee Purchase of 1819, the Indian Agency was moved to the site of Present-day Charleston in 1821.[3] Due to laws passed in Georgia prohibiting the Cherokee from holding public meetings, as well as the Indian Removal Act by the Federal government, the Cherokee began to vacate their capital in New Echota, and in 1832, officially moved the seat of their government to Red Clay.[4] A total of eleven general councils were held at Red Clay between 1832 and 1838, each attended by an estimated 4,000 to 5,000 Cherokees.[5] During the meetings, the Cherokees repeatedly rejected agreements to surrender their lands east of the Mississippi River and move west.[4] With the signing of the Treaty of New Echota on December 29, 1835, which was not approved by the National Council at Red Clay, the Cherokee agreed to give up their lands east of the Mississippi River, and to move to present-day Oklahoma. In February 1836, two councils convened at Red Clay and Valley Town, North Carolina (now Murphy, North Carolina) and produced two lists totaling some 13,000 names, written in the Sequoyah writing script of the Cherokee language, of Cherokee who were opposed to the Treaty. The lists were dispatched to Washington, D.C. and presented by Chief John Ross to Congress. Nevertheless, a slightly modified version of the treaty was ratified by the U.S. Senate by a single vote on May 23, 1836, and signed into law by then-President Andrew Jackson. The treaty provided a grace period until May 1838 for the Cherokees to voluntarily relocate themselves. The Cherokee agency at Charleston served as the headquarters for the removal, which began on May 26, 1838, and many detention camps were located in northern Bradley County between Charleston and Cleveland, with two of the largest at Rattlesnake Springs.[5] The Cherokee removal, which became known as the Trail of Tears, officially began at Red Clay.

A village known as Red Clay was established south of the park on February 29, 1840 in the present site of Cohutta, Georgia.[6]

In the latter half of the 20th century, an effort arose, spearheaded by a number of local historians, to preserve the land of the Red Clay Council Ground, then private land, and turn it into a state park. The Council Grounds were added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) on September 14, 1972,[1] and the state of Tennessee purchased the land for the park in 1974.[7] The site was dedicated as a state park on May 8, 1976 in a ceremony attended by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and local and state leaders.[8] Groundbreaking for the park occurred on April 26, 1978,[9] and Red Clay State Park opened to the public on September 28, 1979.[10] The southeastern most 1.11 acres (0.45 ha) were added to the park on July 2, 1980.[7] The eternal flame was placed on the site on April 6, 1984, at an event attended by both the Eastern and Western Bands of the Cherokee, the first time all three tribes were reunited since the removal.[12]

Description

Located on approximately 263 acres (1.06 km2), Red Clay State Park contains a replica of a Cherokee farmstead and the council house where the final council of the Cherokee was held prior to the removal, all of which once stood on the site.[13] The Eternal Flame of the Cherokee Nation is also located on the site, which serves as a memorial to the Cherokees who suffered and died during the removal and is permanently kept lit. The park contains the iconic Blue Hole Spring, also known as the Council Spring, which was considered sacred to the Cherokees. The spring, which rises out of a bowl-like depression and takes its name from its deep blue color, has runoff which flows into Coahulla Creek, a tributary of the Conasauga River, and has a daily flow of 414,720 gallons.[15] The grave of Sleeping Rabbit, a prominent Cherokee who fought in the War of 1812, is reportedly located in the eastern part of the park. His grave, however, is unmarked.[16]

The park contains three trails, the Connector Trail, Blue Hole Trail, and Council of Trees Trail, with lengths of 0.15 miles (0.24 km), 0.2 miles (0.32 km), and 1.7 miles (2.7 km), respectively, the latter of which has an overlook tower. The Tennessee-Georgia state line forms the southern boundary of the park.[13]

The James F. Corn Interpretive Center features exhibits about 18th and 19th century Cherokee culture, government, economy, recreation, religion and history. A series of stained glass windows depicts the forced removal of the Cherokee and subsequent Trail of Tears emigration. There is also a video about the Cherokee.[7]

The Cherokee Cultural Celebration is held each year in August at the Park. The event, sponsored by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other groups, features exhibitions about Cherokee culture and heritage.[17]

Other nearby Cherokee points of interest are the cabin of Chief John Ross located in Rossville, Georgia[18] and the grave site of Nancy Ward in Benton, Tennessee.

References

- Corn, James F. (1959). Red Clay and Rattlesnake Springs: A History of the Cherokee Indians of Bradley County, Tennessee. Marceline, MO: Walsworth Publishing Company.

- Lillard, Roy G. (1980). Bradley County. Dunn, Joy Bailey., Crawford, Charles Wann, 1931-. Memphis, Tenn.: Memphis State University Press. ISBN 0878700994. OCLC 6934932.

Notes

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Lois Osborne, "Red Clay State Historic Park," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture.

- Lillard 1980, p. 11.

- Forester, Mark (July 31, 1988). "Cherokee History Includes Red Clay". The Oklahoman. Oklahoma City. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- Lillard 1980, p. 12.

- Corn 1959, p. 66.

- Shelton, S. Danielle (February 2019). "Red Clay State Park Cultural Landscape Inventory & Assessment" (PDF). MTSU Center for Historic Preservation. Middle Tennessee State University. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- Higgins, Randall; Rowland, Sandra (May 5, 1976). "Red Clay Dedication Sunday". Cleveland Daily Banner. Cleveland, Tennessee.

- Rowland, Sandra M. (April 27, 1978). "Ground Broken For Red Clay Park". Cleveland Daily Banner. Cleveland, Tennessee.

- Benton, Ben (September 8, 2019). "Red Clay State Historic Park to mark 40th anniversary on Oct. 5". Chattanooga Times Free Press. Chattanooga, Tennessee. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- Sohn, Pam (April 17, 2009). "Cherokees mark historic gathering at Red Clay". Chattanooga Times Free Press. Chattanooga, Tennessee. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- "Red Clay State Historic Park". tnstateparks.com. Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. 2018. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- Corn 1959, p. 71.

- Corn 1959, p. 62.

- Gebby, Kaitlin (August 7, 2019). "Cherokee Cultural Celebration". Cleveland Daily Banner. Cleveland, Tennessee. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- Ross House, Roadsidegeorgia.com, 2003.