African Americans in Tennessee

African Americans are among the largest ethnic groups in the state of Tennessee, making up 17% of the state's population in 2010.[1] African Americans arrived in the region prior to statehood. They lived both as slaves and as free citizens with restricted rights up to the Civil War. The state, and particularly the major cities of Memphis and Nashville have played important roles in African-American culture and the Civil Rights Movement.

Demographics

In the 2010 Census, 1,057,315 Tennessee residents were identified as African-American ( of the total 6,346,105).[2] In just 19 of the state's 95 counties do African Americans make up more than 10% of the population: Shelby (52.1%), Haywood (50.4%), Hardeman (41.4%), Madison (36.3%), Lauderdale (34.9%), Fayette (28.1%), Davidson (27.7%), Lake (27.7%), Hamilton (20.2%), Montgomery (19.1%), Gibson (18.8%), Tipton (18.7%), Dyer (14.3%), Crockett (12.6%), Rutherford (12.5%), Obion (10.6%), Giles (10.2%), and Carroll (10.1%). African Americans in the seven counties of Shelby (483,381), Davidson (173,730), Hamilton (67,900), Knox (38,045), Madison (35,636), Montgomery (32,982), and Rutherford (32,886) make up over 81% of the all African Americans in the state.[3]

The majority-black city of Memphis is home to over four hundred thousand African Americans, making it one of the largest population centers.[4] At least eight other municipalities have African American majorities: Bolivar, Brownsville, Gallaway, Gates, Henning, Mason, Stanton, Whiteville.

Historical population

Davidson County, whose principal city is the state capital of Nashville, was home to the largest share of African Americans from 1800 to 1850. Since 1860, Memphis' Shelby County has had the largest population of African Americans.[5]

| Census year | 1790 | 1800 | 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Tennessee residents[6] | 35,691 | 105,602 | 261,727 | 422,823 | 681,904 | 829,210 | 1,002,717 | 1,109,80, |

| Free Black people[7] | 361 | 309 | 1,318 | 2,739 | 4,511 | 5,524 | 6,442 | 7300 |

| Blacks living in slavery[7] | 3,417 | 13,584 | 44,734 | 80,105 | 141,647 | 183,059 | 239,439 | 275,719 |

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Tennessee |

|

|

|

|

Most of Tennessee's African Americans lived in the condition of slavery from the colonial era until the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865. Although the state played a significant role in early U.S. abolitionism, the state government backed slavery in the 1834 constitution, required newly emancipated Blacks to leave the state, and encouraged European immigration. Nonetheless, a small population of free Blacks remained. Following the 1865 end of slavery, Black Tennesseans played a prominent role in politics during Reconstruction.

Prior to statehood

Early African Americans came to Tennessee from the colonies of Virginia and North Carolina. They, or their parents and grandparents, arrived in North America via the Trans-Atlantic slave trade from West Africa.[8] Early African American arrivals included those purchased as slaves by Cherokee Indians and brought by European traders living in native villages.[9] Wealthy white families from Culpepper, Virginia, brought enslaved African Americans with them to the Powell Valley in southwest Virginia in 1769.[9]

Historian Cynthia Cumfer notes that slavery in early Tennessee was an isolating experience, even in comparison with Virginia and North Carolina. According to 1779-80 records, the vast majority of slaveholders held legal title over just one or two persons, "with the largest holding being ten or eleven slaves." Enslaved African Americans sought out one another through taverns, churches, workplaces, and their owners' kitchens.[10]

The territorial government of Tennessee made early moves to restrict the lives of enslaved persons, denying slaves the right to property, to bear arms (unless designated as the huntsman of their plantation), and to sell goods.[11]

Early statehood

In the 1790 Census, there were 361 free persons of color in Tennessee, and 3,417 people living in slavery.[5] Under Tennessee's first constitution, drafted in 1795 and effective with statehood in 1796, free Blacks were not restricted from voting, although there is no evidence they were permitted to do so in practice.[12]

Public sentiment supporting the abolition of slavery swelled in the first three decades of the 1800s. An 1826 law prohibited the bringing slaves into the state for purposes of sale, rather than the direct use of their labor.[13] Freedmen were required "without fail [to] have [their] emancipation records with [them] at any time and place in order to prove [their] freedom.[13] In 1831, however, the state government mandated that emancipated slaves immediately depart the state, and prohibited the migration of free Blacks to Tennessee.

The 1834 State Constitutional Convention in Nashville defeated a proposal to gradually abolish slavery over a twenty-year period.[14][15] Despite wide-ranging debate, the pro-slavery faction was victorious across the board. The new constitution formally forbid Blacks, slave or free, from voting.[14] It also stripped the legislature of any "power to pass laws for the emancipation of slaves, without the consent of their owner or owners." The right to bear arms was restricted to "the free white men of this State."[16]

Antebellum

Civil War and Reconstruction

Tennessee was the last state to join the Confederacy on June 24, 1861. Nashville was an immediate target of Union forces. In February 1862, it became the first state capital to fall to the Union troops. Union forces moving down the Mississippi River captured Memphis from the Confederacy in the Battle of Memphis on June 6, 1862. Under Union control, both cities swelled with freed slaves and other refugees. Where around 3,000 African Americans lived in Memphis in 1860, some twenty thousand were there by the war's end.[17] African-American troops in the Union Army became a symbol of new social equality, disrupting longstanding patterns of racial deference, publicly bearing arms, and receiving the respect of white officers.[18]

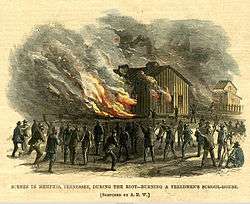

In the aftermath of the war, Memphis became the scene of tensions between white authorities and African American soldiers. The troops effectively countermanded Freedmen's Bureau superintendent Nathan A. M. Dudley's proposal to arrest jobless blacks and send them into contract labor on rural plantations. Black military police also resisted efforts by local white police to close dance houses patronized by whites and to enforce prewar customs of Black deference. After the last Black soldiers at Fort Pickering were discharged on April 30, 1866, confrontation arose. Newly in the status of veterans, armed Blacks confronted police who attempted to arrest one of them. Both sides exchanged gunfire, and a police officer was killed. The veterans retreated to Fort Pickering, where they were disarmed by Union officials. A police-organized posse, which included white laborers, firemen, and small proprietors, began a two-day pillaging of black Memphis, while white Union soldiers did not intervene. These Memphis riots of 1866 resulted in the deaths of 46 blacks and 2 whites, and the destruction by fire of 91 homes, 4 churches and 8 schools.[19]

Post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow

The first hospital that served African-Americans in Tennessee, the Millie E. Hale Hospital, was established in Nashville by a husband and wife team, Dr. John Henry Hale and Millie E. Hale in July 1916.[20][21]

Civil Rights Movement

In 1956, Clinton High School was the first public school to be desegregated by court order. On August 26, 1956 the Clinton 12, Jo Ann Allen, Bobby Cain, Anna Theresser Caswell, Minnie Ann Dickey, Gail Ann Epps, Ronald Hayden, William Latham, Alvah J. McSwain, Maurice Soles, Robert Thacker, Regina Turner, and Alfred Williams, walked from the Green McAdoo School to the high school. On September 1 the white supremacists John Kasper and Asa Carter incited cross burnings and violence. The National Guard was deployed to Clinton for two months. On October 5, 1958 Clinton High School was bombed, nobody was injured, and students had to be bussed to Oak Ridge until 1960.[22]

Nashville and Memphis played central roles in the Civil Rights Movement. In 1957, Nashville public schools began to be desegregated using the "stair-step" plan as proposed by Dan May; people protested integration and, at Hattie Cotton Elementary School, a bomb was detonated. No one was killed, and after that the desegregation plan went on without violence.[23] On February 13, 1960, hundreds of college students involved in the Nashville Student Movement launched a sit-in campaign to desegregate lunch counters throughout the city. Although initially met with violence and arrests, the protesters were eventually successful in pressuring local businesses to end the practice of racial segregation. Many of the activists involved in the Nashville sit-ins—including James Bevel, Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis and others—went on to organize the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which emerged as one of the most influential organizations of the civil rights movement. The first movement credited to SNCC was the 1961 Nashville Open Theater Movement, directed and strategized by James Bevel, which desegregated the city's theaters. Nashville also became a launching site for Freedom Riders in 1961 after the original riders from Washington, D.C., were stopped in Birmingham, Alabama.[24]

A sanitation workers' strike in Memphis in 1968 was linked to both the Civil Rights Movement and the Poor People's Campaign. Martin Luther King, Jr., who had come to the city in support of the striking workers, was assassinated on April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel, the day after giving his prophetic "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech at the Mason Temple. The assassin, James Earl Ray, was a racist escaped convict who had no previous connection to the city.[25]

Recent history

Culture

Political power

African Americans, most of whom were then enslaved, were politically marginal from Tennessee statehood until 1834, when they were denied the right to vote entirely. African American men were granted the right to vote in 1866 by the state's acceptance of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. By the end of 1867, around 40,000 African Americans joined the voter rolls.[26] Following the Reconstruction Era, thirteen African Americans were elected as Republicans to the Tennessee House of Representatives from 1873 to 1888. Among them, David Foote Rivers was elected twice to represent Fayette County as a Republican in 1882 and 1884; however, he was driven out of the county by racial violence and was unable to serve his second term.[27] Additionally, Jesse M. H. Graham was elected to represent Montgomery County in 1896. The sole Black member of the legislature, he was stripped of his seat due to a residency requirement (he had lived in Louisville until October 1895). The Tennessee State Library and Archives notes, "According to several newspaper reports, the General Assembly soon [after] passed a bill blocking the election of black candidates."[28]

Discriminatory ballot restrictions designed to disenfranchise Black voters were enacted via the Dortch Law of 1889. No African American was elected to the Tennessee legislature from 1888 through 1962. Archie Walter Willis Jr. became the first Black legislator in Tennessee in over seven decades in 1964.

Currently, African Americans make up 13% of the legislature; all Black legislators are Democrats.[29] No African American has ever been elected governor or lieutenant governor of Tennessee.

Given the racist method of election in the City of Chattanooga by which all city commissioner positions were elected by majority (white) vote, a federal civil rights lawsuit, "Brown v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Chattanooga" was brought in 1987 against the City of Chattanooga by 12 African American residents. The court found in favor of the African American plaintiffs, and in 1989 the city's governing body was changed to a 9-member council with members elected from 9 districts, determined by census tract and racial demographics, 3 districts of which were majority African American, comprising the majority of the City's 36% African American population. In 2017 four African Americans (1 incumbent, 3 new candidates) were elected to the Chattanooga City Council.

Willie Wilbert Herenton was the first African American elected as Mayor of Memphis. (J. O. Patterson, Jr. was appointed to that office during 1982.) He served five terms from 1991 to 2009. His two successors, Myron Lowery (pro tem, 2009) and A C Wharton, Jr. (2009-2015). Wharton had previously served as Shelby County's first African-American Mayor.

Education

As of 2012, African Americans make up a larger share of the public school system than of the population as a whole. In that year, 230,556 African American students attended pre-Kindergarten through 12th grade public schools, 23.6% of the 935,317 students enrolled overall.[30] Sixty years after Brown v. Board of Education, schooling in Tennessee continues to be substantially segregated by race. During the 2011-12 school year, 44.8% of African American students in Tennessee public schools attended schools that had over 90% minority students (the 9th highest percentage in the nation), while just 25.3% were in majority-white schools.[31]

Racial integration in higher education was prohibited by the 1870 state constitution. After denying admission to seven African Americans in 1937 and 1939, the University of Tennessee admitted its first African American student, Gene Gray, in 1952 under a ruling the prior year that ended the ban for graduate and professional students.[32] Following Brown v. Board of Education and the 1960 Nashville sit-in movement, the UT Board of Trustees announced an end to racial discrimination in admissions on November 18, 1960.[32] In 2014-15, 1,802 of the university's 27,410 students were African American.[33] Memphis State University was integrated in 1959 with the admission of the Memphis State Eight, eight African American students. These students were initially required only to remain on campus for the duration of their classes. Today, black students make up more than one-third of the campus student body and they participate fully in all campus activities.

Tennessee is the site of seven historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). The racially integrated and abolitionist American Missionary Association established eleven universities in the aftermath of the Civil War, including two in Tennessee, LeMoyne Normal and Commercial School at Camp Shiloh in 1862, and Fisk Free Colored School in Nashville in 1866. LeMoyne moved to Memphis in 1863 and is now incorporated in LeMoyne-Owen College; Fisk became the prestigious Fisk University. The Agricultural and Industrial State Normal School, the only publicly funded HBCU in the state, began serving students in 1912. Renamed several times and merged with the predominantly white University of Tennessee at Nashville in 1979, it is now Tennessee State University. The remaining HBCUs are: Knoxville College (1875), Meharry Medical College (1876), Lane College (1882), and American Baptist College (1924).

References

- 17.0% refers to those who selected Black or African American, and no other race in the 2010 Census. U.S. Census Bureau. "Tennessee QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". USA QuickFacts. Archived from the original on 2015-02-07. Retrieved 2015-02-07.

- This figure refers to those who report African American and no other race.

- Tennessee: 2010 Summary Population and Housing Characteristics, US Census Bureau, CPH-1-44

- U.S. Census Bureau. "Memphis (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". USA QuickFacts. Archived from the original on 2015-02-07. Retrieved 2015-02-07.

- Imes, William Lloyd (1919-07-01). "The Legal Status of Free Negroes and Slaves in Tennessee". The Journal of Negro History. 4 (3): 254–272. doi:10.2307/2713777. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2713777.

- Forstall, Richard L.; United States Bureau of the Census Population Division (1996). Population of states and counties of the United States: 1790 to 1990 from the twenty-one decennial censuses. U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Population Division. ISBN 9780934213486.

- Patterson, Caleb Perry (1922). The Negro in Tennessee, 1790-1865: A Study in Southern Politics. University of Texas Bulletin. University of Texas. p. 212. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- "most slaves in both states came from approximately half a dozen countries in West Africa" Cumfer, Cynthia (2007). Separate peoples, one land: The minds of Cherokees, Blacks, and Whites on the Tennessee frontier. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780807831519.

- Cumfer, Cynthia (2007). Separate peoples, one land: The minds of Cherokees, Blacks, and Whites on the Tennessee frontier. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 129. ISBN 9780807831519.

- Cumfer, Cynthia (2007). Separate peoples, one land: The minds of Cherokees, Blacks, and Whites on the Tennessee frontier. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 129–31. ISBN 9780807831519.

- Imes, William Lloyd (1919-07-01). "The Legal Status of Free Negroes and Slaves in Tennessee". The Journal of Negro History. 4 (3): 257. doi:10.2307/2713777. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2713777.

- Imes, William Lloyd (1919-07-01). "The Legal Status of Free Negroes and Slaves in Tennessee". The Journal of Negro History. 4 (3): 261. doi:10.2307/2713777. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2713777.

- Imes, William Lloyd (1919-07-01). "The Legal Status of Free Negroes and Slaves in Tennessee". The Journal of Negro History. 4 (3): 260. doi:10.2307/2713777. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2713777.

- Imes, William Lloyd (1919-07-01). "The Legal Status of Free Negroes and Slaves in Tennessee". The Journal of Negro History. 4 (3): 261. doi:10.2307/2713777. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2713777.

- Morrison, Michael A.; Stewart, James Brewer (2002). Race and the early republic : racial consciousness and nation-building in the early republic. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 147. ISBN 0742521303.

- Laska, Lewis L (1990). The Tennessee State Constitution: a reference guide. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313266539.

- Shaffer, Donald Robert (2004). After the glory: The struggles of Black Civil War veterans. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. p. 33. ISBN 9780700613281.

- Shaffer, Donald Robert (2004). After the glory: The struggles of Black Civil War veterans. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. p. 34. ISBN 9780700613281.

- United States Congress, House Select Committee on the Memphis Riots, Memphis Riots and Massacres, 25 July 1866, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (reprinted by Arno Press, Inc., 1969)

- Rice, Mitchell F.; Rice, Mitchell F.; Jones, Woodrow (1994). Public Policy and the Black Hospital: From Slavery to Segregation to Integration. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-313-26309-5.

- Hart-Brothers, Elaine (1994). "Contributions of Women of Color to the Health Care of America". In Friedman, Emily (ed.). An Unfinished Revolution: Women and Health Care in America. Friedman, Emily. New York: United Hospital Fund of New York. p. 208. ISBN 1-881277-17-8. OCLC 29877915.

- http://www.greenmcadoo.org/about-the-center

- John Egerton, "Walking into History: The Beginning of School Desegregation in Nashville Archived 2010-03-28 at the Wayback Machine," Southern Spaces, May 4, 2009.

- Arsenault, Raymond, 2006. Freedom Riders. Oxford University Press.

- Hampton, Sides. Hellhound on His Trail: The Stalking of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the International Hunt for His Assassin, Doubleday Books, 2010, 480 pp.

- Wright, Sharon D. (2000-09-01). "The Tennessee Black Caucus of State Legislators". Journal of Black Studies. 31 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1177/002193470003100101. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 2645929.

- Tennessee State Library and Archives (2011). "David Foote Rivers". Archived from the original ("This Honorable Body": African American Legislators in 19th Century Tennessee) on 2015-07-24. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Tennessee State Library and Archives (2011). "Jesse M. H. Graham". Archived from the original ("This Honorable Body": African American Legislators in 19th Century Tennessee) on 2015-07-24. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Siner, Emily (2015-01-21). "Tennessee's Legislature Is Mostly Male, Even More White And Virtually All Christian". WPLN Nashville Public Radio. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Tennessee Department of Education (2012). "State Profile". Report Card. Archived from the original on 2015-02-09. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Orfield, Gary; Erica Frankenberg (2014-05-15). Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future. The Civil Rights Project, University of California at Los Angeles. p. 20.

- UT Knoxville. "UT Desegregation Timeline". Celebrating 50 years of African American Achievement. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- UTK Office of Institutional Research & Assessment (2014). "Enrollment Data: 2014-2015". Factbook. Archived from the original on 2015-02-09. Retrieved 2015-02-09.