Sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) mineral particles or rock fragments (clasts) or organic material. They make up about 20 to 25 percent of all sedimentary rocks.[1]

| Sedimentary rock | |

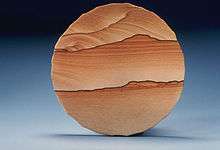

Cut slab of sandstone showing Liesegang banding | |

| Composition | |

|---|---|

| Typically quartz and feldspar; lithic fragments are also common. Other minerals may be found in particularly mature sandstone. |

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) because they are the most resistant minerals to weathering processes at the Earth's surface, as seen in the Goldich dissolution series. Like uncemented sand, sandstone may be any color due to impurities within the minerals, but the most common colors are tan, brown, yellow, red, grey, pink, white, and black. Since sandstone beds often form highly visible cliffs and other topographic features, certain colors of sandstone have been strongly identified with certain regions.

Rock formations that are primarily composed of sandstone usually allow the percolation of water and other fluids and are porous enough to store large quantities, making them valuable aquifers and petroleum reservoirs. Fine-grained aquifers, such as sandstones, are better able to filter out pollutants from the surface than are rocks with cracks and crevices, such as limestone or other rocks fractured by seismic activity.

Quartz-bearing sandstone can be changed into quartzite through metamorphism, usually related to tectonic compression within orogenic belts.

Origins

Sandstones are clastic in origin (as opposed to either organic, like chalk and coal, or chemical, like gypsum and jasper).[2] They are formed from cemented grains that may either be fragments of a pre-existing rock or be mono-minerallic crystals. The cements binding these grains together are typically calcite, clays, and silica. Grain sizes in sands are defined (in geology) within the range of 0.0625 mm to 2 mm (0.0025–0.08 inches). Clays and sediments with smaller grain sizes not visible with the naked eye, including siltstones and shales, are typically called argillaceous sediments; rocks with larger grain sizes, including breccias and conglomerates, are termed rudaceous sediments.

.jpg)

The formation of sandstone involves two principal stages. First, a layer or layers of sand accumulates as the result of sedimentation, either from water (as in a stream, lake, or sea) or from air (as in a desert). Typically, sedimentation occurs by the sand settling out from suspension; i.e., ceasing to be rolled or bounced along the bottom of a body of water or ground surface (e.g., in a desert or erg). Finally, once it has accumulated, the sand becomes sandstone when it is compacted by the pressure of overlying deposits and cemented by the precipitation of minerals within the pore spaces between sand grains.

The most common cementing materials are silica and calcium carbonate, which are often derived either from dissolution or from alteration of the sand after it was buried. Colors will usually be tan or yellow (from a blend of the clear quartz with the dark amber feldspar content of the sand). A predominant additional colourant in the southwestern United States is iron oxide, which imparts reddish tints ranging from pink to dark red (terracotta), with additional manganese imparting a purplish hue. Red sandstones, both Old Red Sandstone and New Red Sandstone, are also seen in the Southwest and West of Britain, as well as central Europe and Mongolia. The regularity of the latter favours use as a source for masonry, either as a primary building material or as a facing stone, over other forms of construction.

Components

Framework grains

Saunders_Quarry-1.jpg)

Framework grains are sand-sized (0.0625-to-2-millimetre (0.00246 to 0.07874 in) diameter) detrital fragments that make up the bulk of a sandstone.[3][4] These grains can be classified into several different categories based on their mineral composition:

- Quartz framework grains are the dominant minerals in most clastic sedimentary rocks; this is because they have exceptional physical properties, such as hardness and chemical stability.[1] These physical properties allow the quartz grains to survive multiple recycling events, while also allowing the grains to display some degree of rounding.[1] Quartz grains evolve from plutonic rock, which are felsic in origin and also from older sandstones that have been recycled.

- Feldspathic framework grains are commonly the second most abundant mineral in sandstones.[1] Feldspar can be divided into two smaller subdivisions: alkali feldspars and plagioclase feldspars. The different types of feldspar can be distinguished under a petrographic microscope.[1] Below is a description of the different types of feldspar.

- Alkali feldspar is a group of minerals in which the chemical composition of the mineral can range from KAlSi3O8 to NaAlSi3O8, this represents a complete solid solution.[1]

- Plagioclase feldspar is a complex group of solid solution minerals that range in composition from NaAlSi3O8 to CaAl2Si2O8.[1]

- Lithic framework grains are pieces of ancient source rock that have yet to weather away to individual mineral grains, called lithic fragments or clasts.[1] Lithic fragments can be any fine-grained or coarse-grained igneous, metamorphic, or sedimentary rock,[1] although the most common lithic fragments found in sedimentary rocks are clasts of volcanic rocks.[1]

- Accessory minerals are all other mineral grains in a sandstone; commonly these minerals make up just a small percentage of the grains in a sandstone. Common accessory minerals include micas (muscovite and biotite), olivine, pyroxene, and corundum.[1][5] Many of these accessory grains are more dense than the silicates that make up the bulk of the rock. These heavy minerals are commonly resistant to weathering and can be used as an indicator of sandstone maturity through the ZTR index.[6] Common heavy minerals include zircon, tourmaline, rutile (hence ZTR), garnet, magnetite, or other dense, resistant minerals derived from the source rock.

Matrix

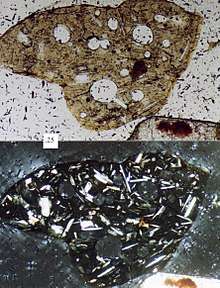

Matrix is very fine material, which is present within interstitial pore space between the framework grains.[1] The nature of the matrix within the interstitial pore space results in a twofold classification:

Cement

Cement is what binds the siliciclastic framework grains together. Cement is a secondary mineral that forms after deposition and during burial of the sandstone.[1] These cementing materials may be either silicate minerals or non-silicate minerals, such as calcite.[1]

- Silica cement can consist of either quartz or opal minerals. Quartz is the most common silicate mineral that acts as cement. In sandstone where there is silica cement present, the quartz grains are attached to cement, which creates a rim around the quartz grain called overgrowth. The overgrowth retains the same crystallographic continuity of quartz framework grain that is being cemented. Opal cement is found in sandstones that are rich in volcanogenic materials, and very rarely is in other sandstones.[1]

- Calcite cement is the most common carbonate cement. Calcite cement is an assortment of smaller calcite crystals. The cement adheres itself to the framework grains, this adhesion is what causes the framework grains to be adhered together.[1]

- Other minerals that act as cements include: hematite, limonite, feldspars, anhydrite, gypsum, barite, clay minerals, and zeolite minerals.[1]

Pore space

Pore space includes the open spaces within a rock or a soil.[7] The pore space in a rock has a direct relationship to the porosity and permeability of the rock. The porosity and permeability are directly influenced by the way the sand grains are packed together.[1]

- Porosity is the percentage of bulk volume that is inhabited by interstices within a given rock.[7] Porosity is directly influenced by the packing of even-sized spherical grains, rearranged from loosely packed to tightest packed in sandstones.[1]

- Permeability is the rate in which water or other fluids flow through the rock. For groundwater, work permeability may be measured in gallons per day through a one square foot cross section under a unit hydraulic gradient.[7]

Types of sandstone

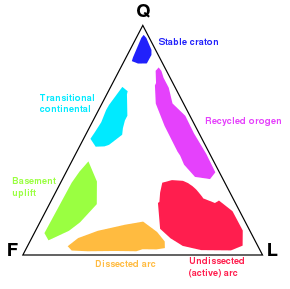

All sandstones are composed of the same general minerals. These minerals make up the framework components of the sandstones. Such components are quartz, feldspars,[8] and lithic fragments. Matrix may also be present in the interstitial spaces between the framework grains.[1] Below is a list of several major groups of sandstones. These groups are divided based on mineralogy and texture. Even though sandstones have very simple compositions which are based on framework grains, geologists have not been able to agree on a specific, right way, to classify sandstones.[1] Sandstone classifications are typically done by point-counting a thin section using a method like the Gazzi-Dickinson Method. The composition of a sandstone can have important information regarding the genesis of the sediment when used with a triangular Quartz, Feldspar, Lithic fragment (QFL diagrams). Many geologists, however, do not agree on how to separate the triangle parts into the single components so that the framework grains can be plotted.[1] Therefore, there have been many published ways to classify sandstones, all of which are similar in their general format.

Visual aids are diagrams that allow geologists to interpret different characteristics about a sandstone. The following QFL chart and the sandstone provenance model correspond with each other therefore, when the QFL chart is plotted those points can then be plotted on the sandstone provenance model. The stage of textural maturity chart illustrates the different stages that a sandstone goes through.

- A QFL chart is a representation of the framework grains and matrix that is present in a sandstone. This chart is similar to those used in igneous petrology. When plotted correctly, this model of analysis creates for a meaningful quantitative classification of sandstones.[9]

- A sandstone provenance chart allows geologists to visually interpret the different types of places from which sandstones can originate.

- A stage of textural maturity is a chart that shows the different stages of sandstones. This chart shows the difference between immature, submature, mature, and supermature sandstones. As the sandstone becomes more mature, grains become more rounded, and there is less clay in the matrix of the rock.[1]

Dott's classification scheme

Dott's (1964) sandstone classification scheme is one of many such schemes used by geologists for classifying sandstones. Dott's scheme is a modification of Gilbert's classification of silicate sandstones, and it incorporates R.L. Folk's dual textural and compositional maturity concepts into one classification system.[10] The philosophy behind combining Gilbert's and R. L. Folk's schemes is that it is better able to "portray the continuous nature of textural variation from mudstone to arenite and from stable to unstable grain composition".[10] Dott's classification scheme is based on the mineralogy of framework grains, and on the type of matrix present in between the framework grains.

In this specific classification scheme, Dott has set the boundary between arenite and wackes at 15% matrix. In addition, Dott also breaks up the different types of framework grains that can be present in a sandstone into three major categories: quartz, feldspar, and lithic grains.[1]

- Arenites are types of sandstone that have less than 15% clay matrix in between the framework grains.

- Quartz arenites are sandstones that contain more than 90% of siliceous grains. Grains can include quartz or chert rock fragments.[1] Quartz arenites are texturally mature to supermature sandstones. These pure quartz sands result from extensive weathering that occurred before and during transport. This weathering removed everything but quartz grains, the most stable mineral. They are commonly affiliated with rocks that are deposited in a stable cratonic environment, such as aeolian beaches or shelf environments.[1] Quartz arenites emanate from multiple recycling of quartz grains, generally as sedimentary source rocks and less regularly as first-cycle deposits derived from primary igneous or metamorphic rocks.[1]

- Feldspathic arenites are sandstones that contain less than 90% quartz, and more feldspar than unstable lithic fragments, and minor accessory minerals.[1] Feldspathic sandstones are commonly immature or sub-mature.[1] These sandstones occur in association with cratonic or stable shelf settings.[1] Feldspathic sandstones are derived from granitic-type, primary crystalline, rocks.[1] If the sandstone is dominantly plagioclase, then it is igneous in origin.[1]

- Lithic arenites are characterised by generally high content of unstable lithic fragments. Examples include volcanic and metamorphic clasts, though stable clasts such as chert are common in lithic arenites.[1] This type of rock contains less than 90% quartz grains and more unstable rock fragments than feldspars.[1] They are commonly immature to submature texturally.[1] They are associated with fluvial conglomerates and other fluvial deposits, or in deeper water marine conglomerates.[1] They are formed under conditions that produce large volumes of unstable material, derived from fine-grained rocks, mostly shales, volcanic rocks, and metamorphic rock.[1]

- Wackes are sandstones that contain more than 15% clay matrix between framework grains.

- Arkose sandstones are more than 25 percent feldspar.[2] The grains tend to be poorly rounded and less well sorted than those of pure quartz sandstones. These feldspar-rich sandstones come from rapidly eroding granitic and metamorphic terrains where chemical weathering is subordinate to physical weathering.

- Greywacke sandstones are a heterogeneous mixture of lithic fragments and angular grains of quartz and feldspar or grains surrounded by a fine-grained clay matrix. Much of this matrix is formed by relatively soft fragments, such as shale and some volcanic rocks, that are chemically altered and physically compacted after deep burial of the sandstone formation.

Uses

Sandstone has been used for domestic construction and housewares since prehistoric times, and continues to be used. Sandstone was a popular building material from ancient times. It is relatively soft, making it easy to carve. It has been widely used around the world in constructing temples, homes, and other buildings.[11] It has also been used for artistic purposes to create ornamental fountains and statues.

Some sandstones are resistant to weathering, yet are easy to work. This makes sandstone a common building and paving material including in asphalt concrete. However, some that have been used in the past, such as the Collyhurst sandstone used in North West England, have been found less resistant, necessitating repair and replacement in older buildings.[12] Because of the hardness of individual grains, uniformity of grain size and friability of their structure, some types of sandstone are excellent materials from which to make grindstones, for sharpening blades and other implements. Non-friable sandstone can be used to make grindstones for grinding grain, e.g., gritstone.

A type of pure quartz sandstone, orthoquartzite, with more of 90–95 percent of quartz,[13] has been proposed for nomination to the Global Heritage Stone Resource.[14] In some regions of Argentina, the orthoquartzite-stoned facade is one of the main features of the Mar del Plata style bungalows.[14]

See also

- Dimension stone – Natural stone that has been finished to specific sizes and shapes

- List of sandstones – Wikipedia list article

- Kurkar – Regional name for an aeolian quartz calcrete on the Levantine coast

- Sedimentary basin – Regions of long-term subsidence creating space for infilling by sediments

- Sydney sandstone

- Yorkstone

Notes

- Boggs, J.R., 2000, Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy, 3rd ed. Toronto: Merril Publishing Company. ISBN 0-13-099696-3

- "A Basic Sedimentary Rock Classification", L.S. Fichter, Department of Geology/Environmental Science, James Madison University (JMU), Harrisonburg, Virginia, October 2000, JMU-sed-classif (accessed: March 2009): separates clastic, chemical & biochemical (organic).

- Dorrik A. V. Stow (2005). Sedimentary Rocks in the Field: A Colour Guide. Manson Publishing. ISBN 978-1-874545-69-9. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- Francis John Pettijohn; Paul Edwin Potter; Raymond Siever (1987). Sand and Sandstone. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-96350-1. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- Prothero, D. (2004). Sedimentary Geology. New York, NN: W.H. Freeman and Company

- Prothero, D. R. and Schwab, F., 1996, Sedimentary Geology, p. 460, ISBN 0-7167-2726-9

- Jackson, J. (1997). Glossary of Geology. Alexandria, VA: American Geological Institute ISBN 3-540-27951-2

- "Sandstone: Sedimentary Rock - Pictures, Definition & More". geology.com. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- Carozzi, A. (1993). Sedimentary petrography. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall ISBN 0-13-799438-9

- Robert H. Dott (1964). "Wacke, greywacke and matrix; what approach to immature sandstone classification?". SEPM Journal of Sedimentary Research. 34 (3): 625–32. doi:10.1306/74D71109-2B21-11D7-8648000102C1865D.

- "Sandstone: Characteristics, Uses And Problems". www.gsa.gov. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- Edensor, T. & Drew, I. Building stone in the City of Manchester: St Ann's Church. Sci-eng.mmu.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2012-05-11.

- "Definition of orthoquartzite – mindat.org glossary". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Cravero, Fernanda; et al. (8 July 2014). "'Piedra Mar del Plata': An Argentine orthoquartzite worthy of being considered as a 'Global Heritage Stone Resource'" (PDF). Geological Society, London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Folk, R.L., 1965, Petrology of sedimentary rocks PDF version. Austin: Hemphill's Bookstore. 2nd ed. 1981, ISBN 0-914696-14-9.

- Pettijohn F. J., P.E. Potter and R. Siever, 1987, Sand and sandstone, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96350-2.

- Scholle, P.A., 1978, A Color illustrated guide to constituents, textures, cements, and porosities of sandstones and associated rocks, American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoir no. 28. ISBN 0-89181-304-7.

- Scholle, P.A., and D. Spearing, 1982, Sandstone depositional environments: clastic terrigenous sediments , American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoir no. 31. ISBN 0-89181-307-1.

- USGS Minerals Yearbook: Stone, Dimension, Thomas P. Dolley, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 2005 (format: PDF).

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sandstone. |

- Webb, Jonathan. Sandstone shapes 'forged by gravity' (July 2014), BBC