Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

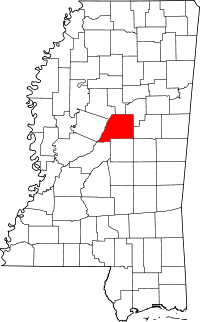

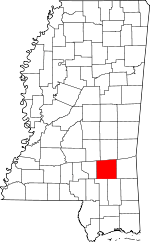

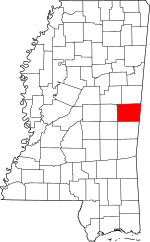

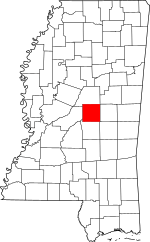

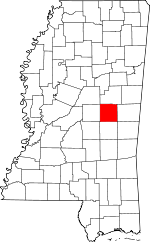

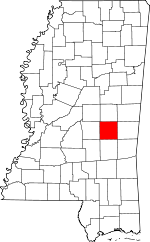

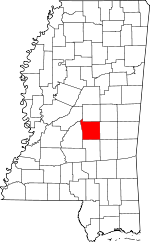

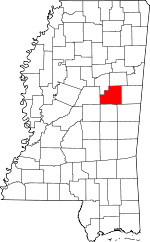

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians is one of three federally recognized tribes of Choctaw Native Americans, and the only one in the state of Mississippi. On April 20, 1945, this band organized under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Also in 1945 the Choctaw Indian Reservation was created in Mississippi by the federal government by acquisition of lands in Neshoba, Leake, Newton, Scott, Jones, Attala, Kemper, and Winston counties. Other federally recognized tribes are the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, the largest, and the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians, a small group located in Louisiana.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ca. 10,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Chahta, English | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, traditional beliefs | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Choctaw tribes, Muscogee Creek, Chickasaw |

By a deed dated August 18, 2008, the state returned Nanih Waiya in Mississippi to the Choctaw. This ancient earthwork mound and site, built ca. 1-300 CE, has been venerated by the Choctaw since the 17th century as a sacred place of origin of their ancestors. The Mississippi Band of Choctaw have made August 18 a tribal holiday to celebrate their regaining control of the sacred site.

History

Indian Removal

The historic Choctaw had emerged as a tribe and occupied substantial territory in what is now considered the state of Mississippi. In the early nineteenth century, they were under increasing pressure by European Americans, who wanted to acquire their land for agricultural development. President Andrew Jackson gained congressional passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 to accomplish this and extinguish Native American land claims in the Southeast.

The chiefs signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek with the United States, which was ratified by the U.S. Senate on February 25, 1831. President Jackson was anxious to make the Choctaw removal a model for other tribes to be taken out of the Southeast to territory well west of the Mississippi River. After ceding close to 11 million acres (45,000 km2), the Choctaw were to emigrate in three stages; the first in the fall of 1831, the second in 1832, and the last in 1833.[2] Although the removals continued into the early 20th century, some Choctaw remained in Mississippi. They continued to live in their ancient homeland. According to the terms of removal, the nearly 5000 Choctaw who remained in Mississippi became citizens of the state and United States.[3]

For the next ten years, they were subject to increasing legal conflict, harassment, and intimidation by white settlers. Racism against them was rampant. The Choctaw described their situation in 1849,

we have had our habitations torn down and burned, our fences destroyed, cattle turned into our fields and we ourselves have been scourged, manacled, fettered and otherwise personally abused, until by such treatment some of our best men have died.[3]

Joseph B. Cobb, a Choctaw who moved to Mississippi from Georgia, described the Choctaw as having

no nobility or virtue at all, and in some respect he found blacks, especially native Africans, more interesting and admirable, the red man's superior in every way. The Choctaw and Chickasaw, the tribes he knew best, were beneath contempt, that is, even worse than black slaves.[4]

American Civil War and Reconstruction

Conditions declined for the Choctaw after the Civil War and Reconstruction. As conservative white Democrats worked to restore white supremacy and eliminate black suffrage, they passed a new constitution in 1890 that effectively disenfranchised blacks through creating barriers to voter registration.[5] In addition, under racial segregation and Jim Crow laws, the whites included all people of color in the category of "other" or Negro (black), and required them to use segregated facilities. Although many mixed-race Choctaw identified culturally as Native American, the whites classified them as black if they had visible African features. Both minority groups were disenfranchised and segregated until after the middle of the twentieth century and passage of federal civil rights laws in the 1960s.

1930s and reorganization

During the Great Depression and the Roosevelt administration, officials began numerous initiatives to alleviate some of the social and economic conditions in the South. The 1933 Special Narrative Report described the dismal state of welfare of the Mississippi Choctaw, whose population by 1930 had declined to 1,665 people.[6] John Collier, the US Commissioner for Indian Affairs (now BIA), used the report as instrumental support in a proposal to re-organize the Mississippi Choctaw as the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. This enabled them to establish their own tribal government, as well as to have a beneficial relationship with the federal government.

In 1934, President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law the Indian Reorganization Act. This law proved critical for survival of the Mississippi Choctaw, Alabama Choctaw and other tribal peoples, who also reorganized in that era. Baxter York, Emmett York, and Joe Chitto worked on gaining recognition for the Choctaw.[7] They realized that they needed to adopt a constitution.[7] A rival organization, the Mississippi Choctaw Indian Federation, opposed federal tribal recognition because of fears of dominance by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). They disbanded after leaders of the opposition were moved to another jurisdiction.[7] The first Tribal Council members of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw were Baxter and Emmett York, with Joe Chitto serving as the first chairperson.[7]

World War II and 1940s

With the tribe's adoption of an elected, representative government, in 1944 the Secretary of the Interior declared that 18,000 acres (73 km2) would be held in trust for the Choctaw of Mississippi, as was done for other federally recognized tribes on reservations. Lands in Neshoba and surrounding counties were set aside as a federal Indian reservation. Eight communities were included in the reservation land: Bogue Chitto, Bogue Homa, Conehatta, Crystal Ridge, Pearl River, Red Water, Tucker, and Standing Pine.

Under the Indian Reorganization Act, the Mississippi Choctaw re-organized on April 20, 1945 as the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. This gave them sovereignty and independence from the state government. The latter continued to be dominated by conservative whites of the Democratic Party, who maintained legal racial segregation and disenfranchisement well into the late twentieth century.

Post-Reorganization, Korean War, and 1950s

In the 1950s, successive Republican administrations (supported by conservative Democrats in the South, which was still a one-party region) became impatient with the gradual assimilation of Native Americans. Republicans proposed to terminate the special status of those tribes that they thought were more fully assimilated. In 1959, the Choctaw Termination Act was passed. Congress settled on a policy to terminate tribes as quickly as possible, believing that was a route of assimilation. In the same period, out of concern for the isolation of many Native Americans on reservations in rural areas, where jobs were scarce, the federal government created relocation programs to cities to try to expand job and cultural opportunities for American Indians. Indian policy experts hoped to expedite assimilation of Native Americans to the larger American society, which was becoming increasingly urbanized.

The Choctaw people continued to struggle economically due to bigotry, cultural isolation, and lack of jobs in their rural area. With reorganization and establishment of tribal government, however, over the next decades they took control of their "schools, health care facilities, legal and judicial systems, and social service programs."[8]

Civil Rights Movement, Vietnam War, and 1960s

In the Civil Rights era, roughly between 1965 and 1982, Native Americans renewed their commitments to the value of their ancient heritage. Working to celebrate their own strengths and to exercise appropriate rights, they dramatically reversed the trend toward abandonment of Indian culture and tradition.[9] During the 1960s, Community Action programs connected with Native Americans were based on citizen participation. Democratic President John F. Kennedy decided against implementing additional termination of tribal status. He did enact some of the last terminations in process, such as that of the Ponca. Both presidents Lyndon Johnson and Republican Richard Nixon repudiated termination of the federal government's special relationships with Native American tribes.

We must affirm the right of the first Americans to remain Indians while exercising their rights as Americans. We must affirm their rights to freedom of choice and self-determination.

— President Lyndon Johnson.

The Choctaw witnessed the social forces that brought Freedom Summer to their ancient homeland. The Civil Rights Era produced significant social change for the Choctaw in Mississippi, as their civil rights were also enhanced as conditions changed for African Americans. Prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, most jobs had been given to whites, with blacks coming second in precedence.[10]

The Choctaw, who for 150 years had identified neither as white nor black, but were discriminated against as people of color, were "left where they had always been"—in poverty.[10] Donna Ladd wrote that a Choctaw, now in her 40s, remembers "as a little girl, she thought that a 'white only' sign in a local store meant she could only order white, or vanilla, ice cream. It was a small story, but one that shows how a third race can easily get left out of the attempts for understanding."[11] The end of legalized racial segregation permitted the Choctaw to participate in public institutions and facilities that had been reserved exclusively for white patrons.

In another major change for state and the federal government, politicians began to support institutionalized gambling to support state programs. Starting with New Hampshire in 1963, numerous state legislatures passed new laws to establish state-run lotteries and other gambling enterprises in order to raise money for government services. Native American tribes began to study gambling enterprises as a means to raise revenues on their reservations to support the economic welfare of their tribes.

1970s and economic development

In the 1970s, the Choctaw repudiated the extremes of Indian activism. Soon after this, Congress passed the landmark Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, completing a 15-year period of federal policy reform with regard to American Indian tribes. The legislation included authorizing tribes to negotiate contracts with the BIA to manage more of their own educational and social service programs. In addition, it provided direct grants to help tribes develop plans for assuming responsibility. It also provided for Indian parents' involvement on school boards.[12]

The American Indian Policy Review Commission, under the Department of Interior, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the Office of Federal Acknowledgment, on May 19, 1977 officially published federal acknowledgement or recognition of the Choctaw Nation of Indians in the original homeland of Mobile and Washington counties of Alabama (the original Mississippi Territory and the same locale as the various Treaties with the Choctaw Nation of Indians on the Tombigbee in 1820 and named again in Alabama in the Choctaw Treaty of 1866). These Alabama Choctaw had been accounted for in the Mississippi Choctaw Jurisdictional Act of 1936, but have been left out of the annals of history under the Color of Law since at least 1937. In 1979 the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians was recognized by the state of Alabama; it does not have formal federal recognition.

Leadership

Phillip Martin, who had served in the U.S. Army in Europe during World War II, returned to Neshoba County, Mississippi to visit his former home. After seeing the poverty of his people, he decided to stay to help.[10] Will D. Campbell, a Baptist minister and civil rights activist, also witnessed the destitution of the Choctaw in the postwar years. He would later write,

the thing I remember the most ... was the depressing sight of the Choctaws, their shanties along the country roads, grown men lounging on the dirt streets of their villages in demeaning idleness, sometimes drinking from a common bottle, sharing a roll-your-own cigarette, their half-clad children a picture of hurting that would never end.[10]

Martin served as chairperson in various Choctaw committees up until 1977. That year he was elected as Chief, or Miko, of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. He served a total of 30 years, being re-elected until 2007.[13]

Beginning in 1979, the tribal council worked on a variety of economic development initiatives, first geared toward attracting industry to the reservation. They had people available to work, natural resources, and no taxes. Industries have included automotive parts, greeting cards, direct mail and printing, and plastic-molding.

1980s-1990s

In 1987 the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that federally recognized tribes could operate gaming facilities on their sovereign reservation land free from state regulation. In 1988 the U.S. Congress enacted the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA); it set the terms for Native American tribes to operate casinos and negotiate terms with states, for instance, paying a portion of revenues in lieu of taxes.[12]

The administration of Governor Ray Mabus had delayed action on Indian gaming in Mississippi, but in 1992 Governor Kirk Fordice gave permission for the Mississippi Band of Choctaw to develop Class III gaming. The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (MBCI) now has one of the largest casino resorts in the nation; it is located in Choctaw, Mississippi. The Silver Star Casino opened in 1994. The Golden Moon Casino opened in 2002. The casinos are collectively known as the Pearl River Resort.

21st century

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians has become one of the state's largest employers. In the early 21st century, they run 19 businesses and employ 7,800 people.[14]

Purporting to represent Native Americans before Congress and state governments to aid them in setting up gaming on their reservation, lobbyists Jack Abramoff and Michael Scanlon used fraudulent means to gain profits of $15 million in payment from the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Abramoff expressed contempt for many of his clients. In an e-mail sent January 29, 2002, Abramoff told Scanlon, "I have to meet with the monkeys from the Choctaw tribal council."[15]

Congressional hearings on the Abramoff scandal were held by the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs in 2006. Federal charges were brought against Abramoff and Scanlon.[16]

In 2002, the United States Congress formally recognized the entire Choctaw Nation in 25 U.S.C. 1779, including those Choctaw in Mobile and Washington counties, Alabama. They were described as Full-Blooded Choctaw equally and in the same Mississippi Choctaw Jurisdictional Act of 1934, by which the Mississippi Band of Choctaw reorganized.

Return of Nanih Waiya

After nearly two hundred years, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw have retaken control of the ancient site of Nanih Waiya, an earthwork mound built about 300-600 AD. They have traditionally venerated this site as their place of origin and the home of their ancestors. For years the state protected the site as a Mississippi state park. It returned Nanih Waiya to the Choctaw in 2006, under Mississippi Legislature State Bill 2803.[17]

The deed was signed on August 18, 2008, which the Choctaw have made a tribal holiday. They have celebrated the day since, and made it an occasion for telling stories of their origin and history, serving traditional foods, and conducting related dances.[18]

Government

The current Miko or tribal chief of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians is Cyrus Ben. Ben was elected in 2019, defeating incumbent tribal chief Phyliss J. Anderson. Ben is the youngest tribal chief elected[19]

In July 2007, Beasley Denson was elected to replace the previous Chief Philip Martin. He served until 2011. Under Denson, the title of Chief was changed to Miko, the Choctaw name for the tribe's leader.

Martin had been democratically elected for seven consecutive terms. Martin had reduced the tribe's 70% unemployment rate in 1997 to less than 3% unemployment in 2007. During his tenure, he led the tribe to become the third-largest employer in Mississippi.

Locations

Old Choctaw country included dozens of towns, such as Lukfata, Koweh Chito, Oka Hullo, Pante, Osapa Chito, Oka Cooply, and Yanni Achukma, located in and around Neshoba and Kemper counties.

The Choctaw regularly traveled hundreds of miles from their homes for long periods of time, moving to seasonal hunting grounds in the winter. They set out early in the fall and returned to their reserved lands at the opening of spring to plant their gardens. At that time they visited the Europeans at Columbus, Mississippi; Macon, Brooksville, and Crawford, and the region where Yazoo City now is located.

Presently, the Mississippi Choctaw Indian Reservation has eight communities.

- Bogue Chitto or "Bok Cito", Mississippi

- Bogue Homa [20]

- Conehatta

- Crystal Ridge

- Henning, Tennessee

- Pearl River

- Red Water

- Tucker

- Standing Pine

These communities are located in parts of nine counties throughout the state. The largest concentration of land is in Neshoba County, at 32°48′56″N 89°14′46″W, which comprises more than two-thirds of the reservation's land area and holds more than 62 percent of its population, as of the 2000 census. The total land area is 84.282 km² (32.541 sq mi), and its official total resident population was 5,190 persons. The nine counties are Neshoba, Newton, Leake, Kemper, Jones, Winston, Attala, Jackson, and Scott counties.

Notable people

- Beasley Denson, tribal chief, 2007—2011

- Jeffrey Gibson, artist

- Phillip Martin, tribal chief, 1978—2007

- Powtawche Valerino, engineer

References

- "History". Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Remini, Robert. "Brothers, Listen ... You Must Submit". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club.

- Walter, Williams (1979). "Three Efforts at Development among the Choctaws of Mississippi". Southeastern Indians: Since the Removal Era. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

- Hudson, Charles (1971). "The Ante-Bellum Elite". Red, White, and Black; Symposium on Indians in the Old South. University of Georgia Press.

- Michael Perman.Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001, Introduction

- Swanton, John Reed (1931). "Choctaw Social and Ceremonial Life". Source Material for the Social and Ceremonial Life of the Choctaw Indians. The University of Alabama Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-8173-1109-2.

- Brescia, William (Bill) (1982). "Chapter 3, Treaties and the Choctaw People". Tribal Government, A New Era. Philadelphia, Mississippi: Choctaw Heritage Press. pp. 21–22.

- Deborah Boykin, "Choctaw Heritage of Louisiana and Mississippi", Louisiana Folklife Program, 2000, accessed 26 Mar 2009

- James H. Howard; Victoria Lindsay Levine (1990). "Introduction". Choctaw Music and Dance. The University of Oklahoma Press. xxi.

- Campbell, Will (1992). "Chapter 13". Providence. Atlanta, Georgia: Long Street Press. p. 243. ISBN 1-56352-024-9.

- Ladd, Donna (2005-06-22). "After Killen: What's Next For Mississippi?". Jackson Free Press. Archived from the original on 2007-03-09. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- William C. Canby, Jr., American Indian Law in a Nut Shell, St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co., pp. 23–33

- "Beasley Denson: Sworn in as Chief of Mississippi Band, Denson assumes title of Miko". Tanasi Journal. 2007-08-14. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- Boykin, Deborah. "Choctaw Indians in the 21st Century". Mississippi History Now. Archived from the original on 2009-02-10. Retrieved 25 Mar 2009.

- U.S. Congress – Committee on Indian Affairs (2004-09-29). "Oversight Hearing In re Tribal Lobbying Matters, et al" (PDF). U.S. Senate. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-01. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- ""Gimme Five"—Investigation of Tribal Lobbying Matters" (PDF). Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. 2006-06-22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-06-28. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- Senator Williamson. "Senate Bill 2803", Mississippi Legislature, 2006 (retrieved 24 September 2011)

- DEBBIE BURT MYERS, "Nanih Waiya Day includes traditional Choctaw dance, food", The Neshoba Democrat, 18 August 2010, accessed 11 October 2011

- Ballou, Howard. "Cyrus Ben takes oath to become youngest Choctaw Tribal Chief in history". www.wlox.com.

- "Bogue Homa". Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Retrieved October 20, 2019.