Clay

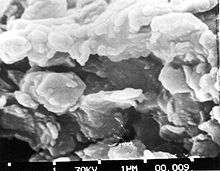

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material that contains hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates (clay minerals) that develops plasticity when wet.[1] Geologic clay deposits are mostly composed of phyllosilicate minerals containing variable amounts of water trapped in the mineral structure. Clays are plastic due to particle size and geometry as well as water content, and become hard, brittle and non–plastic upon drying or firing.[2][3][4] Depending on the soil's content in which it is found, clay can appear in various colours from white to dull grey or brown to deep orange-red.

Although many naturally occurring deposits include both silts and clay, clays are distinguished from other fine-grained soils by differences in size and mineralogy. Silts, which are fine-grained soils that do not include clay minerals, tend to have larger particle sizes than clays. There is, however, some overlap in particle size and other physical properties. The distinction between silt and clay varies by discipline. Geologists and soil scientists usually consider the separation to occur at a particle size of 2 μm (clays being finer than silts), sedimentologists often use 4–5 μm, and colloid chemists use 1 μm.[2] Geotechnical engineers distinguish between silts and clays based on the plasticity properties of the soil, as measured by the soils' Atterberg limits. ISO 14688 grades clay particles as being smaller than 2 μm and silt particles as being larger. Mixtures of sand, silt and less than 40% clay are called loam.

Formation

Clay minerals typically form over long periods as a result of the gradual chemical weathering of rocks, usually silicate-bearing, by low concentrations of carbonic acid and other diluted solvents. These solvents, usually acidic, migrate through the weathering rock after leaching through upper weathered layers. In addition to the weathering process, some clay minerals are formed through hydrothermal activity. There are two types of clay deposits: primary and secondary. Primary clays form as residual deposits in soil and remain at the site of formation. Secondary clays are clays that have been transported from their original location by water erosion and deposited in a new sedimentary deposit.[5] Clay deposits are typically associated with very low energy depositional environments such as large lakes and marine basins.

Grouping

Depending on the academic source, there are three or four main groups of clays: kaolinite, montmorillonite-smectite, illite, and chlorite. Chlorites are not always considered to be a clay, sometimes being classified as a separate group within the phyllosilicates. There are approximately 30 different types of "pure" clays in these categories, but most "natural" clay deposits are mixtures of these different types, along with other weathered minerals.

Varve (or varved clay) is clay with visible annual layers, which are formed by seasonal deposition of those layers and are marked by differences in erosion and organic content. This type of deposit is common in former glacial lakes. When fine sediments are delivered into the calm waters of these glacial lake basins away from the shoreline, they settle to the lake bed. The resulting seasonal layering is preserved in an even distribution of clay sediment banding.[5]

Quick clay is a unique type of marine clay indigenous to the glaciated terrains of Norway, Canada, Northern Ireland, and Sweden. It is a highly sensitive clay, prone to liquefaction, which has been involved in several deadly landslides.

Identification

X-ray diffraction

Powder X-ray diffraction can be used to identify clays.[6]

Historical and modern uses

Clays exhibit plasticity when mixed with water in certain proportions. However, when dry, clay becomes firm, and when fired in a kiln, permanent physical and chemical changes occur. These changes convert the clay into a ceramic material. Because of these properties, clay is used for making pottery, both utilitarian and decorative, and construction products, such as bricks, walls, and floor tiles. Different types of clay, when used with different minerals and firing conditions, are used to produce earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain. Prehistoric humans discovered the useful properties of clay. Some of the earliest pottery shards recovered are from central Honshu, Japan. They are associated with the Jōmon culture, and recovered deposits have been dated to around 14,000 BC.[8] Cooking pots, art objects, dishware, smoking pipes, and even musical instruments such as the ocarina can all be shaped from clay before being fired.

Clay tablets were the first known writing medium.[9] Scribes wrote by inscribing them with cuneiform script using a blunt reed called a stylus. Purpose-made clay balls were used as sling ammunition. Clay is used in many industrial processes, such as paper making, cement production, and chemical filtering. Until the late 20th century, bentonite clay was widely used as a mold binder in the manufacture of sand castings.

Clay, being relatively impermeable to water, is also used where natural seals are needed, such as in the cores of dams, or as a barrier in landfills against toxic seepage (lining the landfill, preferably in combination with geotextiles).[10] Studies in the early 21st century have investigated clay's absorption capacities in various applications, such as the removal of heavy metals from waste water and air purification.[11][12]

Medical use

Traditional uses of clay as medicine goes back to prehistoric times. An example is Armenian bole, which is used to soothe an upset stomach. Some animals such as parrots and pigs ingest clay for similar reasons.[13] Kaolin clay and attapulgite have been used as anti-diarrheal medicines.

As a building material

.jpg)

Clay as the defining ingredient of loam is one of the oldest building materials on Earth, among other ancient, naturally-occurring geologic materials such as stone and organic materials like wood.[14] Between one-half and two-thirds of the world's population, in both traditional societies as well as developed countries, still live or work in buildings made with clay, often baked into brick, as an essential part of its load-bearing structure. Also a primary ingredient in many natural building techniques, clay is used to create adobe, cob, cordwood, and rammed earth structures and building elements such as wattle and daub, clay plaster, clay render case, clay floors and clay paints and ceramic building material. Clay was used as a mortar in brick chimneys and stone walls where protected from water.

See also

- Argillaceous minerals

- Industrial plasticine – A modeling material which is mainly used by automotive design studios

- Clay animation

- Clay chemistry – The chemical structures, properties and reactions of clay minerals

- Clay court

- Clay panel

- Clay pit

- Geophagia – Practice of eating earth or soil-like substrates such as clay or chalk

- Graham Cairns-Smith

- Expansive clay

- London Clay

- Modelling clay

- Paper clay

- Particle size

- Plasticine – Brand of modeling clay

- Vertisol – Clay-rich soil, prone to cracking

- Clay–water interaction – Various progressive interactions between clay minerals and water

Notes

- Olive, W.W.; Chleborad, A.F.; Frahme, C.W.; Shlocker, Julius; Schneider, R.R. & Schuster, R.L. (1989). Swelling Clays Map of the Conterminous United States. U.S. Geological Survey.

- Guggenheim & Martin 1995, pp. 255–256

- "University College London Geology on Campus: Clays". Earth Sciences department, University College London. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- "What is clay". Science Learning Hub. University of Waikato. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- "Environmental Characteristics of Clays and Clay Mineral Deposits". usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008.

- Greene‐Kelly, R. (1953). "The Identification of Montmorillonoids in Clays". Journal of Soil Science. 4 (2): 232–237. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2389.1953.tb00657.x. ISSN 1365-2389.

- Weems, J. B. (1904). "Chemistry of Clays". Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report. 14 (1): 319–346. doi:10.17077/2160-5270.1076. ISSN 2160-5270.

- Scarre, C. 2005. The Human Past, Thames and Hudson: London, p.238

- Ebert, John David (31 August 2011). The New Media Invasion: Digital Technologies and the World They Unmake. McFarland. ISBN 9780786488186. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017.

- Koçkar, Mustafa K.; Akgün, Haluk; Aktürk, Özgür, Preliminary evaluation of a compacted bentonite / sand mixture as a landfill liner material (Abstract) Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Department of Geological Engineering, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey

- García-Sanchez, A.; Alvarez-Ayuso, E.; Rodriguez-Martin, F. (1 March 2002). "Sorption of As(V) by some oxyhydroxides and clay minerals. Application to its immobilization in two polluted mining soils". Clay Minerals. 37 (1): 187–194. Bibcode:2002ClMin..37..187G. doi:10.1180/0009855023710027.

- Churchman, G. J.; Gates, W. P.; Theng, B. K. G.; Yuan, G. (2006). Faïza Bergaya, Benny K. G. Theng and Gerhard Lagaly (ed.). "Chapter 11.1 Clays and Clay Minerals for Pollution Control". Developments in Clay Science. Handbook of Clay Science. Elsevier. 1: 625–675. doi:10.1016/S1572-4352(05)01020-2. ISBN 9780080441832.

- DIAMOND, JARED M. "Diamond on Geophagy". ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015.

- Grim, Ralph. "Clay mineral". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

References

- Guggenheim, Stephen; Martin, R. T. (1995), "Definition of clay and clay mineral: Journal report of the AIPEA nomenclature and CMS nomenclature committees", Clays and Clay Minerals, 43 (2): 255–256, Bibcode:1995CCM....43..255G, doi:10.1346/CCMN.1995.0430213

- Clay mineral nomenclature American Mineralogist.

- Ehlers, Ernest G. and Blatt, Harvey (1982). 'Petrology, Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic' San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-1279-2.

- Hillier S. (2003) "Clay Mineralogy." pp 139–142 In Middleton G.V., Church M.J., Coniglio M., Hardie L.A. and Longstaffe F.J. (Editors) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht. clay is used to make multiple things.

External links

| Look up clay in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clay. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Clay. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Clay |