Little Tennessee River

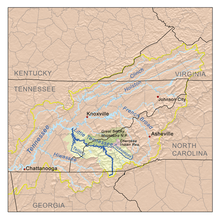

The Little Tennessee River is a 135-mile (217 km) tributary of the Tennessee River that flows through the Blue Ridge Mountains of Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It drains portions of three national forests— Chattahoochee, Nantahala, and Cherokee— and provides the southwestern boundary of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The river flows through five major impoundments: Fontana Dam, Cheoah Dam, Calderwood Dam, Chilhowee Dam, and Tellico Dam, and one smaller impoundment, Porters Bend Dam.

| Little Tennessee River | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Little Tennessee River in North Carolina | |

Little Tennessee River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Keener Creek |

| • location | Rabun County, Georgia |

| • coordinates | 34°57′36″N 83°27′53″W[1] |

| • elevation | 3,240 ft (990 m) |

| 2nd source | Billy Creek |

| • location | Rabun County, Georgia |

| • coordinates | 34°55′17″N 83°27′04″W[2] |

| • elevation | 2,640 ft (800 m) |

| Source confluence | |

| • location | Rabun County, Georgia |

| • coordinates | 34°55′49″N 83°26′11″W[3][4] |

| • elevation | 2,169 ft (661 m) |

| Mouth | Tennessee River |

• location | Lenoir City, Tennessee |

• coordinates | 35°46′57″N 84°15′28″W[3] |

• elevation | 741 ft (226 m)[3] |

| Length | 135 mi (217 km)[5] |

| Basin size | 2,627 sq mi (6,800 km2)[6] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Tallassee, Tennessee (below Chilhowee Dam), 33 miles (53 km) above the mouth(mean for water years 1958–1979)[7] |

| • average | 5,012 cu ft/s (141.9 m3/s)(mean for water years 1958–1979)[7] |

| • minimum | 20 cu ft/s (0.57 m3/s)October 1974[7] |

| • maximum | 41,500 cu ft/s (1,180 m3/s)May 1973[7] |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Tennessee → Ohio → Mississippi |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Nantahala River, Cheoah River, Citico Creek, Tellico River |

| • right | Tuckasegee River, Hazel Creek, Abrams Creek |

Course

The Little Tennessee River rises in the Blue Ridge Mountains, in the Chattahoochee National Forest in northeast Georgia's Rabun County. After flowing north through the mountains past Dillard into southwestern North Carolina, it is joined by the Cullasaja River at Franklin. The river then turns northwest, flowing through the Nantahala National Forest along the north side of the Nantahala Mountains. It crosses into eastern Tennessee and joins the Tennessee River at Lenoir City, 25 miles (40 km) southwest of Knoxville.

Impoundments

The lower river is impounded several places by sequential dams, some created as part of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) system; they form a string of reservoirs in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee down to the river's confluence with the Tennessee. Near the state line between North Carolina and Tennessee, the Little Tennessee River is impounded by the 480-foot (150 m) Fontana Dam, completed in 1944, forming Fontana Lake along the southern boundary of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. It is also impounded by Cheoah Dam in North Carolina, and by Calderwood and Chilhowee dams in Tennessee. The reservoirs provide flood control and hydroelectric power.

Calderwood and Cheoah dams divert water through short tunnels slightly downstream of the dams themselves to hydroelectric generators. Chilhowee has power generators built straight into the dam itself. Some water is also diverted from the nearby Santeetlah Dam on the Cheoah River to power another hydroelectric generator at the Santeetlah Powerhouse. This water is brought to the Little Tennessee River through 7 miles (11 km) of tunnels through the Great Smoky Mountains. Chilhowee, Calderwood, and Cheoah Dams and the Santeetlah Powerhouse were originally built by Alcoa to power the aluminum plant at Alcoa, Tennessee. To ensure efficiency in operation, Alcoa coordinates the operation of its hydro system with TVA, making sure that reservoir and river water levels are safe for recreational use (primarily boating and fishing) and that proper flows of water continue down the river.

The final impoundment is Tellico Dam, which is just above its mouth into the Tennessee River at Lenoir City, Tennessee. It creates Tellico Reservoir. The dam does not have its own hydroelectric generators but serves to increase the flow through those at nearby Fort Loudoun Dam on the Tennessee by means of a canal which diverts much of the flow of the Little Tennessee. The plan to build the dam was the subject of environmental controversy during the 1970s regarding the snail darter, an endangered species.[8] It was the first major legal challenge to the Endangered Species Act.

History

The Little Tennessee River and its immediate watershed comprise one of the richest archaeological areas in the southeastern United States, containing substantial habitation sites dating back to as early as 7,500 B.C.[9] Cyrus Thomas, who conducted a survey of earthwork mounds in the area for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s, wrote that the Little Tennessee River was "undoubtedly the most interesting archaeological section in the entire Appalachian district."[10]

.jpg)

Substantial Archaic period (8000-1000 B.C.) sites along the river include the Icehouse Bottom and the Rose Island sites, both located near the river's confluence with the Tellico River.[11] These sites were probably semi-permanent base camps, the inhabitants of which may have sought the chert deposits on the bluffs above the river which they used to create tools.[12]

Evidence of Woodland period (1000 B.C. - 1000 A.D.) habitation has been uncovered at numerous sites along the Little Tennessee, most notably at Icehouse Bottom, Rose Island, Calloway Island (near the river's confluence with Toqua Creek), Thirty Acre Island (near the river's confluence with Nine Mile Creek) and Bacon Bend (between Toqua and Citico Beach). Excavations in the 1970s uncovered large groups of Woodland-period burials on both Rose and Calloway islands.[13] Pottery fragments uncovered at Icehouse Bottom in the 1970s show evidence of interaction with the Hopewell people of what is now Ohio.[14]

Mississippian period (c. 1000-1500 A.D.) sites in the Little Tennessee Valley include the Toqua site (at the river's confluence with Toqua Creek), Tomotley (adjacent to Toqua), Citico (at the river's Citico Creek confluence), and Bussell Island (at the mouth of the river).[15] Toqua's Mississippian inhabitants constructed a 25-foot (7.6 m) platform mound overlooking a central plaza. By 1400, the village covered 4.8 acres (0.019 km2) surrounded by a clay-covered palisade.[16]

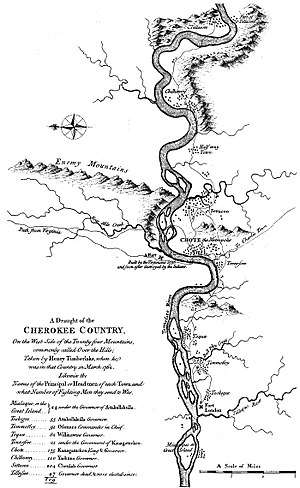

Several Cherokee Middle towns, including Nikwasi, Jore, and Cowee were located along the river's North Carolina section.[17] The river was also home to most of the major Overhill Cherokee towns, the most prominent of which included Chota, Tanasi, Toqua, Tomotley, Mialoquo (near Rose Island), Chilhowee (at the river's Abrams Creek confluence), Tallassee (near modern Calderwood), Citico, and Tuskegee (adjacent to Fort Loudoun).[18]

Euro-American traders were visiting the Overhill towns along the Little Tennessee by the late 17th century, and there is some evidence that Hernando De Soto and Juan Pardo passed through the Little Tennessee Valley in 1540 and 1567, respectively.[19] In 1756 the English built Fort Loudoun, located at the river's confluence with the Tellico River. The fort has been reconstructed as an historic site. Two early American sites are located along the Little Tennessee— the Tellico Blockhouse, an outpost at the river's Nine Mile Creek confluence, and Morganton, a river port and ferry town near modern Greenback that thrived in the early 19th century.[20] The Hazel Creek section of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, located on the north shore of the river's Fontana Lake impoundment, was home to a substantial Appalachian community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[21]

See also

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Keener Creek

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Billy Creek

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Little Tennessee River

- Adrian Holt, Coweeta LTER, and Little Tennessee Watershed Association, "Upper Little Tennessee Watershed Water and Habitat Quality Education Curriculum," Coweeta Longterm Ecological Research (LTER) website. Retrieved: 4 June 2015.

- Marcos Luna, The Environment Since 1945 (Infobase Learning, 2012), p. 161.

- U.S. Geological Survey, "Introduction to the Upper Tennessee River Basin," 11 January 2013. Accessed: 31 May 2015.

- United States Geological Survey, Water Resources Data Tennessee: Water Year 1979, Water Data Report TN-79-1, p. 192. Gaging station 03518300 (discontinued in 1979).

- Richard Polhemus, The Toqua Site — 40MR6, Vol. I (Norris, Tenn.: Tennessee Valley Authority, 1987), 1.

- Jefferson Chapman, Tellico Archaeology: 12,000 Years of Native American History (Norris, Tenn.: Tennessee Valley Authority, 1985), 41.

- Chapman, Tellico Archaeology, 16.

- Jay Franklin, "Archaic Period," The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: 26 January 2008.

- Chapman, Tellico Archaeology, 40-41.

- Chapman, Tellico Archaeology, 63-67.

- James Stoltman, "Icehouse Bottom and the Hopewell Connection Archived 2008-07-23 at the Wayback Machine," Frank H. McClung Museum Research Notes, February 1999. Retrieved: 27 January 2008.

- Polhemus, The Toqua Site — 40MR6 Vol. II, 1240-1246.

- Chapman, Tellico Archaeology, 79.

- William Steele, The Cherokee Crown of Tannassy (Winston-Salem: John F. Blair, 1977), map on inside cover.

- Chapman, Tellico Archaeology, 100.

- Chapman, Tellico Archaeology, 97.

- Alberta and Carson Brewer, Valley So Wild (Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1975), 94-97.

- Duane Oliver, Hazel Creek From Then Till Now (Maryville, Tenn.: Stinnett Printing, 1989), 1-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Little Tennessee River. |