Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was a battle in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, fought April 6–7, 1862, in southwestern Tennessee. A Union force known as the Army of the Tennessee (Major General Ulysses S. Grant) had moved via the Tennessee River deep into Tennessee and was encamped principally at Pittsburg Landing on the west bank of the Tennessee River, where the Confederate Army of Mississippi (General Albert Sidney Johnston, P. G. T. Beauregard second-in-command) launched a surprise attack on Grant's army from its base in Corinth, Mississippi. Johnston was mortally wounded during the fighting; Beauregard took command of the army and decided against pressing the attack late in the evening. Overnight, Grant was reinforced by one of his divisions stationed farther north and was joined by three divisions from the Army of the Ohio (Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell). The Union forces began an unexpected counterattack the next morning which reversed the Confederate gains of the previous day.

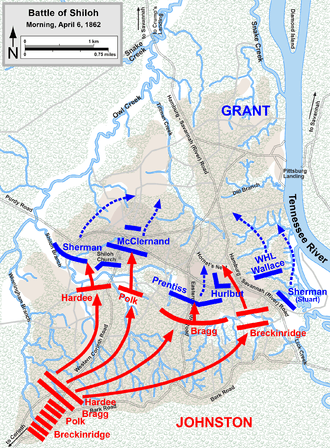

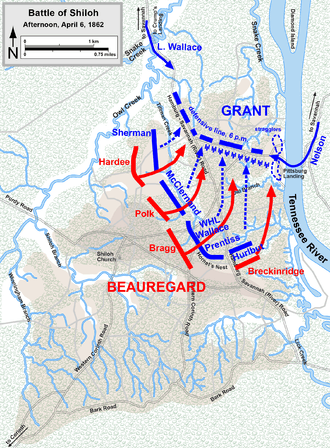

On April 6, the first day of the battle, the Confederates struck with the intention of driving the Union defenders away from the river and into the swamps of Owl Creek to the west. Johnston hoped to defeat Grant's army before the anticipated arrival of Buell and the Army of the Ohio. The Confederate battle lines became confused during the fighting, and Grant's men instead fell back to the northeast, in the direction of Pittsburg Landing. A Union position on a slightly sunken road, nicknamed the "Hornet's Nest" and defended by the divisions of Brig. Gens. Benjamin Prentiss and William H. L. Wallace, provided time for the remainder of the Union line to stabilize under the protection of numerous artillery batteries. Wallace was mortally wounded when the position collapsed, while several regiments from the two divisions were eventually surrounded and surrendered. Johnston was shot in the leg and bled to death while leading an attack. Beauregard acknowledged how tired the army was from the day's exertions and decided against assaulting the final Union position that night.

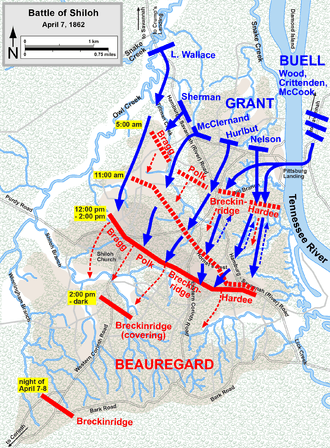

Tired but unfought and well-organized men from Buell's army and a division of Grant's army arrived in the evening of April 6 and helped turn the tide the next morning, when the Union commanders launched a counterattack along the entire line. Confederate forces were forced to retreat, ending their hopes of blocking the Union advance into northern Mississippi. Though victorious, the Union army had suffered heavier casualties than the Confederates, and Grant was heavily criticized in the media for being taken by surprise.

The Battle of Shiloh was the bloodiest engagement of the Civil War to date, with nearly twice as many casualties as the previous major battles of the war combined.

Background and plans

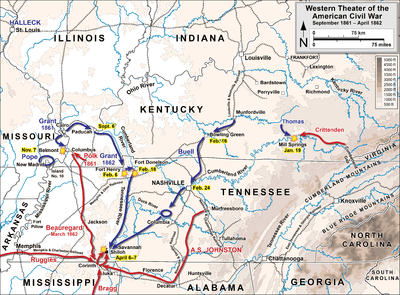

After the beginning of the American Civil War, the Confederacy sought to defend the Mississippi River valley, the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, and the Cumberland Gap, all of which provided invasion routes into the center of the Confederacy. The neutral state of Kentucky initially provided a buffer for the Confederacy in the region as it controlled the territory Union troops would have to pass through in an advance along these routes but in September 1861 General Leonidas Polk occupied Columbus, Kentucky, prompting the state to join the Union. This opened Kentucky to Union forces, prompting Confederate President Jefferson Davis to appoint General Albert Sidney Johnston, a respected antebellum army officer, to take charge of Confederate forces in the Western Theater. Under Johnston, Columbus was fortified to block the Mississippi, Forts Henry and Donelson were established on the Cumberland and Tennessee, Bowling Green, Kentucky, garrisoned astride the Louisville and Nashville, and Cumberland Gap occupied.[15]

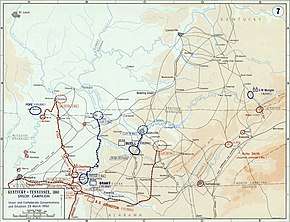

With numerical superiority, the Union could concentrate troops to break through the Confederate line at a single point and bypass Columbus. Major General Henry Halleck was given command of the Union forces in the Mississippi Valley and in late 1861 decided to focus on the Tennessee River as the major axis of advance. While the Union victory at the Battle of Mill Springs in January 1862 unhinged the Confederate right flank, Ulysses S. Grant's army captured Forts Henry and Donelson in February, with Grant's insistence on the unconditional surrender of their garrisons elevating him to national hero status. The fall of the twin forts opened the Tennessee and Cumberland as invasion routes and allowed for the outflanking of the Confederate forces in the west.[16] These reverses forced Johnston to withdraw his forces into western Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and Alabama to reorganize. Johnston established his base at Corinth, Mississippi, the site of a major railroad junction and strategic transportation link between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mississippi River, but left the Union troops with access into southern Tennessee and points farther south via the Tennessee River.[17]

In early March, Halleck, then commander of the Department of the Missouri, ordered Grant to remain at Fort Henry, and on March 4 turned field command of the expedition over to a subordinate, Brig. Gen. C. F. Smith, who had recently been nominated as a major general.[18] (Various writers assert that Halleck took this step because of professional and personal animosity toward Grant; however, Halleck shortly restored Grant to full command, perhaps influenced by an inquiry from President Abraham Lincoln.)[19] Smith's orders were to lead raids intended to capture or damage the railroads in southwestern Tennessee. Brig. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman's troops arrived from Paducah, Kentucky, to conduct a similar mission to break the railroads near Eastport, Mississippi.[20] Halleck also ordered Grant to advance his Army of West Tennessee (soon to be known by its more famous name, the Army of the Tennessee) on an invasion up the Tennessee River. Grant left Fort Henry and headed upriver (south), arriving at Savannah, Tennessee, on March 14, and established his headquarters on the east bank of the river. Grant's troops set up camp farther upriver: five divisions at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, and a sixth at Crump's Landing, four miles from Grant's headquarters.[21]

Meanwhile, Halleck's command was enlarged through consolidation of Grant's and Buell's armies and renamed the Department of the Mississippi. With Buell's Army of the Ohio under his command, Halleck ordered Buell to concentrate with Grant at Savannah.[22] Buell began a march with much of his army from Nashville, Tennessee, and headed southwest toward Savannah. Halleck intended to take the field in person and lead both armies in an advance south to seize Corinth, Mississippi, where the Mobile and Ohio Railroad linking Mobile, Alabama, to the Ohio River intersected the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. The railroad was a vital supply line connecting the Mississippi River at Memphis, Tennessee to Richmond, Virginia.[23]

Opposing forces and initial movements

Union

Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee of 44,895[7][24] men consisted of six divisions:

- 1st Division (Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand): 3 brigades;

- 2nd Division (Brig. Gen. W. H. L. Wallace): 3 brigades;

- 3rd Division (Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace): 3 brigades;

- 4th Division (Brig. Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut): 3 brigades;

- 5th Division (Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman): 4 brigades;

- 6th Division (Brig. Gen. Benjamin M. Prentiss): 2 brigades;[3]

Of the six divisions encamped on the western side of the Tennessee River in early April, only Lew Wallace's 3rd Division was at Crump's Landing; the remainder were farther south (upriver) at Pittsburg Landing. Grant developed a reputation during the war for being more concerned with his own plans than with those of the enemy.[25][26] His encampment at Pittsburg Landing displayed his most consequential lack of such concern—his army was spread out in bivouac style, with many of his men surrounding a small, log meetinghouse named Shiloh Church, passing the time waiting for Buell's army with drills for his many raw troops without establishing entrenchments or other significant defensive measures. However, major crossings into the encampment were guarded and patrols frequently dispatched.[27]

In his memoirs, Grant justified his lack of entrenchments by recounting that he did not consider them necessary, believing "drill and discipline were worth more to our men than fortifications." Grant wrote that he "regarded the campaign we were engaged in as an offensive one and had no idea that the enemy would leave strong intrenchments to take the initiative when he knew he would be attacked where he was if he remained."[28][27] Lew Wallace's division was 5 miles (8.0 km) downstream (north) from Pittsburg Landing, at Crump's Landing, a position intended to prevent the placement of Confederate river batteries, to protect the road connecting Crump's Landing to Bethel Station, Tennessee, and to guard the Union army's right flank. In addition, Wallace's troops could strike the railroad line connecting Bethel Station to Corinth, about 20 miles (32 km) to the south.[29]

The portion of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell's Army of the Ohio that was engaged in the battle consisted of four divisions:

- 2nd Division (Brig. Gen. Alexander M. McCook): 3 brigades;

- 4th Division (Brig. Gen. William "Bull" Nelson): 3 brigades;

- 5th Division (Brig. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden): 2 brigades;

- 6th Division (Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood): 2 brigades;

On April 5, the eve of battle, the first of Buell's divisions, under the command of Brig. Gen. William "Bull" Nelson, reached Savannah. Grant instructed Nelson to encamp there instead of immediately crossing the river. The remainder of Buell's army, still marching toward Savannah with only portions of four of his divisions, totaling 17,918 men,[26] did not reach the area in time to have a significant role in the battle until its second day. Buell's three other divisions were led by Brig. Gens. Alexander M. McCook, Thomas L. Crittenden, and Thomas J. Wood. (Wood's division appeared too late even to be of much service on the second day.)[30]

Confederate

On the Confederate side, Albert S. Johnston named his newly assembled force the Army of Mississippi.[lower-alpha 1] He concentrated almost 55,000 men around Corinth, Mississippi, about 20 miles (32 km) southwest of Grant's troops at Pittsburg Landing. Of these men, 40,335[9][10] departed from Corinth on April 3, hoping to surprise Grant before Buell arrived to join forces. They were organized into four large corps, commanded by:

- I Corps (Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk), with 2 divisions under Brig. Gen. Charles Clark and Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham;

- II Corps (Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg), with 2 divisions under Brig. Gens. Daniel Ruggles and Jones M. Withers;

- III Corps (Maj. Gen. William J. Hardee), with 3 brigades under Brig. Gens. Thomas C. Hindman, Patrick Cleburne, and Sterling A. M. Wood;

- Reserve Corps (Brig. Gen. John C. Breckinridge), with 3 brigades under Cols. Robert Trabue and Winfield S. Statham, and Brig. Gen. John S. Bowen, and attached cavalry;[26]

Comparison between Union and Confederate armies

On the eve of battle, Grant's and Johnston's armies were of comparable size, but the Confederates were poorly armed with antique weapons, including shotguns, hunting rifles, pistols, flintlock muskets, and even a few pikes; however, some regiments had recently received Enfield rifles.[31] The troops approached the battle with very little combat experience; Braxton Bragg's men from Pensacola and Mobile were the best trained. Grant's army included 32 out of 62 infantry regiments who had combat experience at Fort Donelson. One half of his artillery batteries and most of his cavalry were also combat veterans.[32]

Johnston's plan

P.G.T. Beauregard[33]

Johnston's plan was to attack Grant's left, separate the Union army from its gunboat support and avenue of retreat on the Tennessee River, and drive it west into the swamps of Snake and Owl Creeks, where it could be destroyed. The attack on Grant was originally planned for April 4, but it was delayed for 48 hours due to a heavy rain storm that turned roads into seas of mud, causing some units to get lost in the woods and others to grind to a halt faced with heavy traffic jams. It ended up taking Johnston 3 days to move his army just 23 miles.[34] This was a significant setback for the Confederate Army, as the originally scheduled attack would have commenced when Buell's Army of the Ohio was too far away to be of any aid to Grant. Instead, it would happen on the 6th with Buell's army close at hand and able to reinforce Grant on the second day. Furthermore, the delay left the Confederate Army desperately short of rations. They had issued their troops 5 days of rations just before leaving Corinth, but failure to properly conserve their food intake and the two-day delay left most troops completely out of rations by the time the battle commenced.[35]

During the Confederate march, there were several minor skirmishes with Union scouts and both sides had taken prisoners.[36] Furthermore, many Confederate troops failed to maintain proper noise discipline as the army prepared for the attack. Positioned only a few miles from the Union Army, the rebel soldiers routinely played their bugles, pounded their drums, and even discharged their muskets hunting for game.[34] As a result, Johnston's second in command, P. G. T. Beauregard, feared that the element of surprise had been lost and recommended withdrawing to Corinth, believing that by the time the battle commenced, they would be facing an enemy "entrenched up to the eyes".[37] He was also concerned about the lack of rations, fearing that if the army got into prolonged engagement, their meager remaining food supplies would not be able to sustain them. But Johnston once more refused to consider retreat.[38]

Johnston made the decision to attack, stating "I would fight them if they were a million."[39] Despite Beauregard's well-founded concern, most of the Union forces did not hear the marching army approach and were unaware of the enemy camps less than 3 miles (4.8 km) away.[40]

Battle, April 6 (first day: Confederate assault)

Early morning attack

Before 6 a.m. on Sunday, April 6, Johnston's army was deployed for battle, straddling the Corinth Road. The army had spent the entire night making a camp in order of battle within 2 miles (3.2 km) of the Union camp near Sherman's headquarters at Shiloh Church.[41] Despite several contacts, a few minor skirmishes with Union forces, and the failure of the army to maintain proper noise discipline in the days leading up to the 6th, their approach and dawn assault achieved a strategic and tactical surprise. Grant wanted to avoid provoking any major battles until the linkup with Buell's Army of the Ohio was complete. Thus the Union army had sent out no scouts or regular patrols and did not have any vedettes in place for early warning, concerned that scouts and patrols might provoke a major battle before the Army of the Ohio finished crossing the river.[42] Grant telegraphed a message to Halleck on the night of April 5, "I have scarcely the faintest idea of an attack (general one) being made upon us, but will be prepared should such a thing take place."[43] Grant's declaration proved to be overstated. Sherman, the informal camp commander at Pittsburg Landing, did not believe the Confederates had a major assault force nearby; he discounted the possibility of an attack from the south. Sherman expected that Johnston would eventually attack from the direction of Purdy, Tennessee, to the west. When Col. Jesse Appler of the 53rd Ohio Infantry warned Sherman that an attack was imminent, the general angrily replied, "Take your damned regiment back to Ohio. There are no Confederates closer than Corinth."[43]

Around 3 a.m., Col. Everett Peabody, commanding Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss's 1st Brigade, sent a patrol of 250 infantry men from the 25th Missouri and the 12th Michigan out on reconnaissance patrol, convinced that the constant reports of Confederate contacts over the last few days meant there was a strong possibility of a large confederate force in the area. The patrol, under the command of Maj. James E. Powell, met fire from Confederates who then fled into the woods. A short time later, 5:15 a.m., they encountered Confederate outposts manned by the 3rd Mississippi Battalion, and a spirited fight lasted about an hour. Arriving messengers and sounds of gunfire from the skirmish alerted the nearest Union troops, who formed battle line positions before the Confederates were able to reach them;[39] however, the Union army command had not adequately prepared for an attack on their camps.[44] When Prentiss learned that Peabody had sent out a patrol without his authorization he was outraged and accused the Colonel of provoking a major engagement in violation of Grant's orders, but he soon realized he was facing an assault by an entire Confederate army and rushed to prepare his men for defense.[45] By 9 a.m. Union forces at Pittsburg Landing were either engaged or moving toward the front line.[46] Both Peabody and Powell were soon killed in the subsequent fighting.[47]

The confusing alignment of the Confederate army helped reduce the effectiveness of the attack, since Johnston and Beauregard had no unified battle plan. Earlier, Johnston had telegraphed Confederate President Jefferson Davis his plan for the attack: "Polk the left, Bragg the center, Hardee the right, Breckinridge in reserve."[48] His strategy was to emphasize the attack on his right flank to prevent the Union army from reaching the Tennessee River, its supply line and avenue of retreat. Johnston instructed Beauregard to stay in the rear and direct men and supplies as needed, while he rode to the front to lead the men on the battle line. This effectively ceded control of the battle to Beauregard, who had a different concept, which was simply to attack in three waves and push the Union army eastward to the river.[49][lower-alpha 3] The corps of Hardee and Bragg began the assault with their divisions in one line, nearly 3 miles (4.8 km) wide and about 2 miles (3.2 km) from its front to its rear column.[50] As these units advanced, they became intermingled and difficult to control. Recognizing the disorganization, the Confederate corps commanders divided responsibility for sectors of the line among themselves as the first attack progressed, but this made division commanders redundant in most cases and in some cases placed them over subordinates who they had not personally met before.[51] Corps commanders attacked in line without reserves, and artillery could not be concentrated to effect a breakthrough. At about 7:30 a.m., from his position in the rear, Beauregard ordered the corps of Polk and Breckinridge forward on the left and right of the line, diluting their effectiveness. The attack therefore went forward as a frontal assault conducted by a single linear formation, which lacked both the depth and weight needed for success. Command and control, in the modern sense, were lost from the onset of the first assault.[52]

Grant and his army rally

The Confederate assault, despite its shortcomings, was ferocious, causing some of the numerous inexperienced Union soldiers in Grant's new army to flee to the river for safety. Others fought well, but were forced to withdraw under strong pressure from the Confederates, and attempted to form new defensive lines. Many Union regiments fragmented entirely; the companies and sections that remained on the field attached themselves to other commands. Sherman, who had been negligent in preparing for an attack, became one of its most important elements. He appeared everywhere along his lines, inspiring his raw recruits to resist the initial assaults, despite the staggering losses on both sides. Sherman received two minor wounds and had three horses shot out from under him. Historian James M. McPherson cites the battle as the turning point of Sherman's life, helping him to become one of the North's premier generals.[53] Sherman's division bore the brunt of the initial attack. Despite heavy fire on their position and their left flank crumbling, Sherman's men fought stubbornly, but the Union troops slowly lost ground and fell back to a position behind Shiloh Church. McClernand's division temporarily stabilized the position. Overall, however, Johnston's forces made steady progress until noon, rolling up Union positions one by one.[54] As the Confederates advanced, many threw away their flintlock muskets and grabbed rifles dropped by the fleeing Union troops.[55]

By 11:00 am, the Confederate advance began to slow down, due to stiff Union resistance, but also due to disciplinary problems as the army overran the Federal camps. The sight of fresh food still burning on camp fires proved too tempting for many hungry Confederates, and many broke ranks to pillage and loot the camps, putting the army on hold until their officers could get them back into line. Johnston himself ended up personally intervening to help prevent the looting and get his army back on track. Riding into the Union camp, he took a single tin cup and announced "Let this be my share of the spoils today," before directing his army onward.[56]

Grant was about 10 miles (16 km) downriver at Savannah, Tennessee, when he heard the sound of artillery fire. (On April 4, he had been injured when his horse fell and pinned him underneath. He was convalescing and unable to move without crutches.)[57] Before leaving Savannah, Grant ordered Bull Nelson's division to march along the east side of the river, to a point opposite Pittsburg Landing, where it could be ferried over to the battlefield. Grant then took his steamboat, Tigress, to Crump's Landing, where he gave Lew Wallace his first orders, which were to wait in reserve and be ready to move.[58] Grant proceeded to Pittsburg Landing, arriving about 8:30 a.m.; most of the day went by before the first of these reinforcements arrived. (Nelson's division arrived around 5 p.m.; Wallace's appeared about 7 p.m.[59]) Wallace's slow movement to the battlefield would become particularly controversial.[60]

Lew Wallace's division

On the morning of April 6, around 8:00 or 8:30 a.m., Grant's flagship stopped alongside Wallace's boat moored at Crump's Landing and gave orders for the 3rd Division to be held ready to move in any direction. Wallace concentrated his troops at Stoney Lonesome, although his westernmost brigade remained at Adamsville. He then waited for further orders, which arrived between 11 and 11:30 a.m.[61] Grant ordered Wallace to move his unit up to join the Union right, a move that would have been in support of Sherman's 5th Division, which was encamped around Shiloh Church when the battle began. The written orders, transcribed from verbal orders that Grant gave to an aide, were lost during the battle and controversy remains over their wording.[62] Wallace maintained that he was not ordered to Pittsburg Landing, which was to the left rear of the army, or told which road to use. Grant later claimed that he ordered Wallace to Pittsburg Landing by way of the River Road (also called the Hamburg–Savannah Road).[63]

Around noon, Wallace began the journey along the Shunpike, a route familiar to his men.[64] A member of Grant's staff, William R. Rowley, found Wallace between 2 and 2:30 p.m. on the Shunpike, after Grant wondered where Wallace was and why he had not arrived on the battlefield, while the main Union force was being slowly pressed backward. Rowley told Wallace that the Union army had retreated, Sherman was no longer fighting at Shiloh Church, and the battle line had moved northeast toward Pittsburg Landing.[65] If Wallace continued in the same direction, he would have found himself in the rear of the advancing Confederate troops.[66]

Wallace had to make a choice: he could launch an attack and fight through the Confederate rear to reach Grant's forces closer to Pittsburg Landing, or reverse his direction and march toward Pittsburg Landing via a crossroads to the River Road. Wallace chose the second option.[67] (After the war, Wallace claimed that his division might have attacked and defeated the Confederates if his advance had not been interrupted,[68] but later conceded that the move would not have been successful[69] Rather than realign his troops so the rear guard would be in the front, Wallace made a controversial decision to countermarch his troops to maintain the original order, only facing in the other direction. The move further delayed Wallace's troops as they marched north along the Shunpike road, then took a crossover to reach the River Road to the east, and headed south toward the battlefield.[70]

Wallace's division began arriving at Grant's position about 6:30 p.m., after a march of about 14 miles (23 km) in seven hours over poor and muddy roads. It formed line on the battlefield about 7 p.m., when the fighting was nearly over for the day.[71] Although Grant showed no disapproval at the time, his later endorsement of Wallace's battle report was negative enough to severely damage Wallace's military career.[72] Today, Wallace's reputation is somewhat better, thanks to his actions at the July 9, 1864 Battle of Monocacy (aka "The Battle that Saved Washington") which delayed Jubal Early's attack by a critical 24 hours, allowing Union reinforcements from Petersburg just enough time to arrive and fortify Washington's defenses and defeat Early on July 12. Wallace is also now remembered as the author of Ben-Hur.[73]

Hornet's Nest

.jpg)

On the main Union defensive line, starting around 9 a.m., Prentiss's and W. H. L. Wallace's divisions established and held a position nicknamed the "Hornet's Nest", in a field along a road, now popularly called the "Sunken Road," although there is little physical justification for that name.[74] The Confederates assaulted the position for several hours rather than simply bypassing it, and suffered heavy casualties. Historians' estimates of the number of separate charges range from 8 to 14.[lower-alpha 4] The Union forces to the left and right of the Nest were forced back, making Prentiss's position a prominent point in the line. Coordination within the Nest was poor, and units withdrew based solely on their individual commanders' decisions. The pressure increased when W. H. L. Wallace, commander of the largest concentration of troops in the position, was mortally wounded while attempting to lead a breakout from the Confederate encirclement.[75] Union regiments became disorganized and companies disintegrated as the Confederates, led by Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles, assembled more than 50 cannons into "Ruggles's Battery",[lower-alpha 5] the largest concentration of artillery ever assembled in North America up to that point, to blast the line at close range.[76] Confederates surrounded the Hornet's Nest, and it fell after holding out for seven hours. Prentiss surrendered himself and the remains of his division to the Confederates. A large portion of the Union survivors, an estimated 2,200 to 2,400 men, were captured, but their sacrifice bought time for Grant to establish a final defense line near Pittsburg Landing.[77][lower-alpha 6]

While dealing with the Hornet's Nest, the South suffered a serious setback with the death of their commanding general. Albert Sidney Johnston had received a report from Breckenridge that one of his brigades was refusing orders to advance against a Union force in a peach orchard. Quickly rushing to the scene, Johnston was able to rally the men to make the charge by leading it personally, and was mortally wounded at about 2:30 p.m. as he led the attacks on the Union left through the Widow Bell's cotton field against the Peach Orchard.[78] Johnston was shot in his right leg, behind the knee.[79] Deeming the wound insignificant, Johnston continued on leading the battle.[80]

Eventually, Johnston's staff members noticed him slumping in his saddle. One of them, Tennessee governor Isham Harris, asked Johnston if he was wounded, and the general replied "Yes, and I fear seriously."[81] Earlier in the battle, Johnston had sent his personal surgeon to care for the wounded Confederate troops and Yankee prisoners, and there were no medical staff at his current location.[82] An aide helped him off his horse and laid him down under a tree, then went to fetch his surgeon, but did not apply a tourniquet to Johnston's wounded leg. Before a doctor could be found, Johnston bled to death from a torn popliteal artery that caused internal bleeding and blood to collect unnoticed in his riding boot.[83][lower-alpha 7]

Jefferson Davis considered Johnston to be the most effective general they had (this was two months before Robert E. Lee emerged as the preeminent Confederate general). Johnston was the highest-ranking officer from either side to be killed in combat during the Civil War. Beauregard assumed command, but his position in the rear, where he relied on field reports from his subordinates, may have given him only a vague idea of the disposition of forces at the front.[84][lower-alpha 8] Beauregard ordered Johnston's body shrouded for secrecy to avoid lowering morale and resumed attacks against the Hornet's Nest. This was likely a tactical error, because the Union flanks were slowly pulling back to form a semicircular line around Pittsburg Landing. If Beauregard had concentrated his forces against the flanks, he might have defeated the Union army at the landing, and then reduced the Hornet's Nest position at his leisure.[85]

Defense at Pittsburg Landing

The Union flanks were being pushed back, but not decisively. In the face of the advance of Hardee and Polk against the Union right, Sherman and McClernand mounted a fighting retreat in the direction of Pittsburg Landing,[86] leaving the right flank of the Hornet's Nest exposed. Just after Johnston's death, Breckinridge, whose corps had been in reserve, attacked on the extreme left of the Union line, driving off the understrength brigade of Col. David Stuart and potentially opening a path into the Union rear and the Tennessee River. However, the Confederates paused to regroup and recover from exhaustion and disorganization, then moved toward the Hornet's Nest.[87] The flanking attack on the latter has been attributed by historians to the Confederates moving to the sound of the guns, though Samuel Lockett on Bragg's staff recalled that Bragg dispatched him and Franklin Gardner to order the attack.[88]

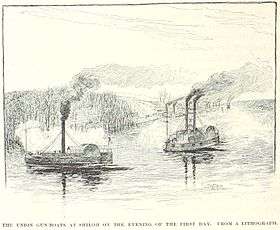

After the Hornet's Nest fell, the remnants of the Union line established a solid three-mile (5 km) front around Pittsburg Landing, extending west from the river and then north, up the River Road, keeping the approach open for the expected, although belated, arrival of Lew Wallace's division. Sherman commanded the right of the line, McClernand took the center, and on the left, the remnants of W. H. L. Wallace's, Hurlbut's, and Stuart's men mixed with thousands of stragglers[lower-alpha 9] who were crowding on the bluff over the landing. The advance of Buell's army, Col. Jacob Ammen's brigade of Bull Nelson's division, arrived in time to be ferried over and join the left end of the line.[89] The defensive line included a ring of more than 50 cannons[lower-alpha 10] and naval guns from the river (the gunboats USS Lexington and USS Tyler).[91] A final Confederate charge of two brigades, led by Brig. Gen. Withers, attempted to break through the line but was repulsed. Beauregard called off a second attempt after 6 p.m., as the sun set.[92] The Confederate plan had failed; they had pushed Grant east to a defensible position on the river where he could be re-enforced and resupplied, not cut him off from his supply lines by forcing him west into the swamps in accordance with the original battle plan.[87]

Evening lull

The evening of April 6 was a dispiriting end to the first day of one of the bloodiest battles in American history. The cries of wounded and dying men on the fields between the armies could be heard in the Union and Confederate camps throughout the night. Exhausted Confederate soldiers bedded down in the abandoned Union camps. The Union troops were pushed back to the river and the junction of the River (Hamburg–Savannah Road) and the Corinth-Pittsburg Landing Roads.[93] Around 10 p.m. a thunderstorm passed through the area. Coupled with the continuous shelling from the Union gunboats Lexington and Tyler, it made the night a miserable experience for both sides.[69]

In his 1885 memoirs, Grant described his experience that night:

During the night rain fell in torrents and our troops were exposed to the storm without shelter. I made my headquarters under a tree a few hundred yards back from the river bank. My ankle was so much swollen from the fall of my horse the Friday night preceding, and the bruise was so painful, that I could get no rest. The drenching rain would have precluded the possibility of sleep without this additional cause. Some time after midnight, growing restive under the storm and the continuous pain, I moved back to the loghouse under the bank. This had been taken as a hospital, and all night wounded men were being brought in, their wounds dressed, a leg or an arm amputated as the case might require, and everything being done to save life or alleviate suffering. The sight was more unendurable than encountering the enemy's fire, and I returned to my tree in the rain.[94]

A famous anecdote encapsulates Grant's unflinching attitude to temporary setbacks and his tendency for offensive action. Sometime after midnight, Sherman encountered Grant standing under a tree, sheltering himself from the pouring rain and smoking one of his cigars, while considering his losses and planning for the next day. Sherman remarked, "Well, Grant, we've had the devil's own day, haven't we?" Grant looked up. "Yes," he replied, followed by a puff. "Yes. Lick 'em tomorrow, though."[95]

Nathan Bedford Forrest to Patrick R. Cleburne[96]

Beauregard sent a telegram to President Davis announcing a complete victory. He later admitted, "I thought I had Grant just where I wanted him and could finish him up in the morning."[97] Many of his men were jubilant, having overrun the Union camps and taken thousands of prisoners and tons of supplies. Grant still had reason to be optimistic: Lew Wallace's 5,800 men (minus the two regiments guarding the supplies at Crump's Landing) and 15,000 of Don Carlos Buell's army began to arrive that evening. Wallace's division took up a position on the right of the Union line and was in place by 1 a.m.;[5] Buell's men were fully on the scene by 4 a.m., in time to turn the tide the next day.[98]

Beauregard caused considerable historical controversy with his decision to halt the assault at dusk. Braxton Bragg and Albert Sidney Johnston's son, Col. William Preston Johnston, were among those who bemoaned the so-called "lost opportunity at Shiloh." Beauregard did not come to the front to inspect the strength of the Union lines; he remained at Shiloh Church. He also discounted intelligence reports from Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest (and bluster from prisoner of war General Prentiss[lower-alpha 11]) that Buell's men were crossing the river to reinforce Grant. In defense of his decision, Beauregard's troops were simply exhausted, there was less than an hour of daylight left, and Grant's artillery advantage was formidable. In addition, he had received a dispatch from Brig. Gen. Benjamin Hardin Helm in northern Alabama that indicated Buell was marching toward Decatur and not Pittsburg Landing.[100]

Battle, April 7 (second day: Union counterattack)

On Monday morning, April 7, the combined Union armies numbered 45,000 men. The Confederates had suffered as many as 8,500 casualties the first day and their commanders reported no more than 20,000 effectives due to stragglers and deserters. (Buell disputed that figure after the war, stating that there were 28,000). The Confederates had withdrawn south into Prentiss's and Sherman's former camps, while Polk's corps retired to the Confederate bivouac established on April 5, which was 4 miles (6.4 km) southwest of Pittsburg Landing. No line of battle was formed, and few if any commands were resupplied with ammunition. The soldiers were consumed by the need to locate food, water, and shelter for a much-needed night's rest.[101]

Beauregard, unaware that he was now outnumbered, planned to continue the attack and drive Grant into the river. To his surprise, Union forces started moving forward in a massive counterattack at dawn. Grant and Buell launched their attacks separately; coordination occurred only at the division level. Lew Wallace's division was the first to see action, about 5:30 a.m., at the extreme right of the Union line.[102] Wallace continued the advance, crossing Tilghman Branch around 7 a.m. and met little resistance. Changing direction and moving to the southwest, Wallace's men drove back the brigade of Col. Preston Pond. On Wallace's left were the survivors of Sherman's division, then McClernand's, and W. H. L. Wallace's (now under the command of Col. James M. Tuttle). Buell's army continued to the left with Bull Nelson's, Crittenden's, and McCook's divisions. The Confederate defenders were so badly commingled that little unit cohesion existed above the brigade level. It required more than two hours to locate Gen. Polk and bring up his division from its bivouac to the southwest. By 10 a.m., Beauregard had stabilized his front with his corps commanders from left to right: Bragg, Polk, Breckinridge, and Hardee.[103] In a thicket near the Hamburg-Purdy Road, the fighting was so intense that Sherman described in his report of the battle "the severest musketry fire I ever heard."[104][lower-alpha 12]

On the Union left, Nelson's division led the advance, followed closely by Crittenden's and McCook's men, down the Corinth and Hamburg-Savannah roads. After heavy fighting, Crittenden's division recaptured the Hornet's Nest area by late morning, but the Crittenden and Nelson forces were repulsed by determined counterattacks from Breckinridge. Wallace's and Sherman's men on the Union right made steady progress, driving Bragg and Polk to the south. As Crittenden and McCook resumed their attacks, Breckinridge was forced to retire. By noon Beauregard's line paralleled the Hamburg-Purdy Road.[105]

In early afternoon, Beauregard launched a series of counterattacks from the Shiloh Church area, aiming to control the Corinth Road. The Union right was temporarily driven back by these assaults at Water Oaks Pond. Crittenden, reinforced by Tuttle, seized the junction of the Hamburg-Purdy and East Corinth roads, driving the Confederates into Prentiss's old camps. Nelson resumed his attack and seized the heights overlooking Locust Grove Branch by late afternoon. Beauregard's final counterattack was flanked and repulsed when Grant moved Col. James C. Veatch's brigade forward.[106]

Grant later wrote of a close call he and his staff officers had during the fighting in which they personally came under heavy fire, stating "During this second day of the battle I had been moving from right to left and back, to see for myself the progress made. In the early part of the afternoon, while riding with Colonel McPherson and Major Hawkins, then my chief commissary, we got beyond the left of our troops. We were moving along the northern edge of a clearing, very leisurely, toward the river above the landing. There did not appear to be an enemy to our right, until suddenly a battery with musketry opened upon us from the edge of the woods on the other side of the clearing. The shells and balls whistled about our ears very fast for about a minute. I do not think it took us longer than that to get out of range and out of sight. In the sudden start we made, Major Hawkins lost his hat. He did not stop to pick it up. When we arrived at a perfectly safe position we halted to take an account of damages. McPherson's horse was panting as if ready to drop. On examination it was found that a ball had struck him forward of the flank just back of the saddle, and had gone entirely through. In a few minutes the poor beast dropped dead; he had given no sign of injury until we came to a stop. A ball had struck the metal scabbard of my sword, just below the hilt, and broken it nearly off; before the battle was over it had broken off entirely. There were three of us: one had lost a horse, killed; one a hat and one a sword-scabbard. All were thankful that it was no worse."[107]

Confederate retreat

Realizing that he had lost the initiative, was low on ammunition and food, and had more than 10,000 of his men killed, wounded, or missing, Beauregard could go no further. He withdrew beyond Shiloh Church, leaving 5,000 men under Breckinridge as a covering force, and massed Confederate batteries at the church and on the ridge south of Shiloh Branch. Confederate forces kept the Union men in position on the Corinth Road until 5 p.m., then began an orderly withdrawal southwest to Corinth. The exhausted Union soldiers did not pursue much farther than the original Sherman and Prentiss encampments. Lew Wallace's division crossed Shiloh Branch and advanced nearly 2 miles (3.2 km), but received no support from other units and was recalled. They returned to Sherman's camps at dark.[108] The battle was over.

For long afterwards, Grant and Buell quarreled over Grant's decision not to mount an immediate pursuit with another hour of daylight remaining. Grant cited the exhaustion of his troops, although the Confederates were certainly just as exhausted. Part of Grant's reluctance to act could have been the unusual command relationship he had with Buell. Although Grant was the senior officer and technically was in command of both armies, Buell made it quite clear throughout the two days that he was acting independently.[109]

Fallen Timbers, April 8

On April 8, Grant sent Sherman south along the Corinth Road on a reconnaissance in force to confirm that the Confederates had retreated, or if they were regrouping to resume their attacks. Grant's army lacked the large organized cavalry units that would have been better suited for reconnaissance and vigorous pursuit of a retreating enemy. Sherman marched with two infantry brigades from his division, along with two battalions of cavalry, and met Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood's division of Buell's army. Six miles (10 km) southwest of Pittsburg Landing, Sherman's men came upon a clear field in which an extensive camp was erected, including a Confederate field hospital. The camp was protected by 300 troopers of Confederate cavalry, commanded by Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest. The road approaching the field was covered by fallen trees for more than 200 yards (180 m).[110]

As skirmishers from the 77th Ohio Infantry approached, having difficulty clearing the fallen timber, Forrest ordered a charge. The wild melee, with Confederate troops firing shotguns and revolvers and brandishing sabers, nearly resulted in Forrest's capture. As Col. Jesse Hildebrand's brigade began forming in line of battle, the Southern troopers started to retreat at the sight of the strong force, and Forrest, who was well in advance of his men, came within a few yards of the Union soldiers before realizing he was all alone. Sherman's men yelled out, "Kill him! Kill him and his horse!"[111] A Union soldier shoved his musket into Forrest's side and fired, striking him above the hip, penetrating to near the spine. Although he was seriously wounded, Forrest was able to stay on horseback and escape; he survived both the wound and the war. The Union lost about 100 men, most of them captured during Forrest's charge, in an incident that has been remembered with the name "Fallen Timbers". After capturing the Confederate field hospital, Sherman encountered the rear of Breckinridge's covering force, but determined the enemy was making no signs of renewing its attack and withdrew back to the Union camps.[112][lower-alpha 13]

Aftermath

In his memoirs, Grant intimated that

The battle of Shiloh, or Pittsburg landing, has been perhaps less understood, or to state the case more accurately, more persistently misunderstood, than any other engagement between National and Confederate troops during the entire rebellion. Correct reports of the battle have been published, notably by Sherman, Badeau and, in a speech before a meeting of veterans, by General Prentiss; but all of these appeared long subsequent to the close of the rebellion and after public opinion had been most erroneously formed

— Ulysses S. Grant[113]

Reactions and effects

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Northern newspapers vilified Grant for his performance during the battle on April 6, especially for being surprised and unprepared. Reporters, many far from the battle, spread the story that Grant had been drunk, falsely alleging that this had resulted in many of his men being bayoneted in their tents because of a lack of defensive preparedness. Despite the Union victory, Grant's reputation suffered in Northern public opinion. Many credited Buell with taking control of the broken Union forces and leading them to victory on April 7. Calls for Grant's removal overwhelmed the White House. President Lincoln replied with one of his most famous quotations about Grant: "I can't spare this man; he fights."[114] Although all of the Union division commanders fought well, Sherman emerged as an immediate hero after Grant and Halleck commended him especially. His steadfastness under fire and amid chaos atoned for his previous melancholy and his defensive lapses preceding the battle.[115] Army officers that were with Grant gave a starkly different account of his capacity, and performance, than those of enterprising newspaper reporters far away from Grant during the battle. One such officer, Colonel William R. Rowley, answering a letter of inquiry about allegations aimed at Grant, maintained:

I pronounce it an unmitigated slander. I have been on his Staff ever since the Donelson affair (and saw him frequently during that) and necessary in close contact with him every day, and I have never seen him take even a glass of liquor more than two or three times in my life and then only a single at a time. And I have never seen him intoxicated or even approximate to it. As to the story that he was intoxicated at the Battle of Pittsburg, I have only to say that the man who fabricated the story is an infamous liar, and you are at liberty to say to him that I say so. ...

— Yours &c W R ROWLEY[116]

In retrospect, however, Grant is recognized positively for the clear judgment he was able to retain under the strenuous circumstances, and his ability to perceive the larger tactical picture that ultimately resulted in victory on the second day.[117][118] For the rest of his life, Grant would insist he always had the battle well under control and rejected claims from critics that only the death of Johnston and arrival of Buell's Army prevented his defeat. In his 1885 memoirs, he wrote:

Some of these critics claim that Shiloh was won when Johnston fell, and that if he had not fallen the army under me would have been annihilated or captured. Ifs defeated the Confederates at Shiloh. There is little doubt that we would have been disgracefully beaten if all the shells and bullets fired by us had passed harmlessly over the enemy and if all of theirs had taken effect. Commanding generals are liable to be killed during engagements; and the fact that when he was shot Johnston was leading a brigade to induce it to make a charge which had been repeatedly ordered, is evidence that there was neither the universal demoralization on our side nor the unbounded confidence on theirs which has been claimed. There was, in fact, no hour during the day when I doubted the eventual defeat of the enemy, although I was disappointed that reinforcements so near at hand did not arrive at an earlier hour.[119]

Subsequent events

Grant's career suffered temporarily in the aftermath of Shiloh; Halleck combined and reorganized his armies, relegating Grant to the powerless position of second-in-command.[120] Beauregard remained in command of the Army of Mississippi and led it back to Corinth.[121] In late April and May, the Union armies, under Halleck advanced slowly toward Corinth and took it in the Siege of Corinth, while an amphibious force on the Mississippi River destroyed the Confederate River Defense Fleet and captured Memphis, Tennessee. Halleck was promoted to be general in chief of all the Union armies and with his departure to the East, Grant was restored to command. The Union forces eventually pushed down the Mississippi River to besiege Vicksburg, Mississippi. After the surrender of Vicksburg and the fall of Port Hudson in the summer of 1863, the Mississippi River came under Union control and the Confederacy was cut in two.[122]

Davis was outraged at Beauregard for withdrawing from Corinth without a fight, even though he faced an army nearly twice his size and his water supplies in the city had become contaminated. Shortly after the fall of Corinth, Beauregard took medical leave without receiving authorization from Davis. This was the final straw for Davis, who quickly reassigned him to oversee the coastal defenses in South Carolina. Command of the Army of Mississippi fell to Braxton Bragg, who was promoted to full general on April 6 and during the fall of 1862, he led it on an abortive invasion of Kentucky, culminating in his retreat from the Battle of Perryville.[123]

The Union General Lew Wallace was heavily criticized for failing to get his division into the battle until 1830 hours, near the end of combat on the first day. He was removed from the Army of the Tennessee and never again received a front line command or took part in a big offensive operation, though his backwater assignments still placed him in important battles. Shortly after Shiloh, he was sent to the War Department in Ohio where he led the successful Defense of Cincinnati during Bragg's invasion of Kentucky. In 1864, at the Battle of Monocacy, Wallace commanded a 5,800 man force to oppose Jubal Early's 14,000-man invasion of Maryland. Faced against an army more than twice his size, Wallace was eventually forced to retreat to Baltimore, but his men delayed Early's advance for a full day, enabling Union re-enforcement to be brought up to protect Washington D.C. Despite this success and later fame for writing the book Ben Hur, criticism of Wallace's conduct at Shiloh would haunt him for the rest of his life and he would spend much of it trying to defend his actions there.[124]

Casualties

The two-day battle of Shiloh, the costliest in American history up to that time,[lower-alpha 14] resulted in the defeat of the Confederate army and frustration of Johnston's plans to prevent the two Union armies in Tennessee from joining together. Union casualties were 13,047 (1,754 killed, 8,408 wounded, and 2,885 missing); Grant's army bore the brunt of the fighting over the two days, with casualties of 1,513 killed, 6,601 wounded, and 2,830 missing or captured. Confederate casualties were 10,699 (1,728 killed, 8,012 wounded, and 959 missing or captured).[126][lower-alpha 15] The dead included the Confederate army's commander, Albert Sidney Johnston, as well as Brigadier General Adley H. Gladden.[127] George W. Johnson, the head of Kentucky's shadow Confederate government, was also mortally wounded.[128] The highest ranking Union general killed was W. H. L. Wallace.[129] Union Colonel Everett Peabody, whose decision to send out a patrol the morning of the battle may have saved the Union from disaster, was also among the dead. Both sides were shocked at the carnage, which resulted in nearly twice as many casualties as the previous major battles of the war combined:[lower-alpha 16]

I saw an open field, in our possession on the second day, over which the Confederates had made repeated charges the day before, so covered with dead that it would have been possible to walk across the clearing, in any direction, stepping on dead bodies, without a foot touching the ground.

— Ulysses S. Grant[113]

Grant later came to realize that his prediction of one great battle bringing the war to a close would probably not occur. The war would continue, at great cost in casualties and resources, until the Confederacy succumbed or the Union was divided. Grant also learned a valuable personal lesson on preparedness that (mostly) served him well for the rest of the war.[130]

Significance

The loss of Albert Sidney Johnston dealt a severe blow to Confederate morale. Contemporaries saw his death, and their defeat as the beginning of the end for the Confederacy: President Jefferson Davis called it "the turning point of our fate," while Confederate brigade commander Randall L. Gibson believed that "the West perished with Albert Sidney Johnston, and the Southern country followed."[131] With the Confederate loss, their best opportunity to retake the Mississippi Valley and achieve numerical superiority with the Union armies in the west disappeared, and the heavy losses suffered at Shiloh represented the start of an unwinnable war of attrition.[132][133]

Battlefield preservation

Shiloh's importance as a Civil War battle, coupled with the lack of widespread agricultural or industrial development in the battle area after the war, led to its development as one of the first five battlefields restored by the federal government in the 1890s, when the Shiloh National Military Park was established under the administration of the War Department; the National Park Service took over the park in 1933.[134] The federal government had saved just over 2,000 acres at Shiloh by 1897, and consolidated those gains by adding another 1,700 acres by 1954, these efforts gradually dwindled and government involvement proved insufficient to preserve the land on which the battle took place. Since 1954, only 300 additional acres of the saved land had been preserved.[135] Private preservation organizations stepped in to fill the void. The Civil War Trust became the primary agent of these efforts, joining federal, state and local partners to acquire and preserve 1,317 acres (5.33 km2) of the battlefield in more than 25 different acquisitions since 1996. Much of the acreage has been sold or conveyed to the National Park Service and incorporated into the Shiloh National Military Park.[136][137] The land preserved by the Trust at Shiloh included tracts over which Confederate divisions passed as they fought Grant's men on the battle's first day and their retreat during the Union counteroffensive on day two. A 2012 campaign focused in particular on a section of land which was part of the Confederate right flank on day one and on several tracts which were part of the Battle of Fallen Timbers.[138]

Honors and commemoration

The United States Postal Service released a commemorative stamp on the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Shiloh, first issued through the Shiloh, Tennessee, Post Office on April 7, 1962. It was the second in a series of five stamps marking the Civil War Centennial.[139]

Notes

- During the battle, correspondence referred to the army as the Army of the Mississippi, deviating from the general rule that only Union armies were named after rivers. See, for instance, the NPS website. It was also sometimes referred to as the Army of the West. The army was activated on March 5, 1862, and was renamed by Braxton Bragg as the Army of Tennessee in November. See Army of Mississippi.

- 66,812 according to Eicher 2001, pp. 222–23 (Army of the Tennessee: 48,894; Army of the Ohio: 17,918)

- Esposito 1959 Map 34 text states that that Johnston was severely criticized for this arrangement with Beauregard, but there was some justification since Johnston's had many inexperienced recruits in his army that needed personal inspiration at the front.

- Eicher 2001, p. 227 cites 12. Daniel 1997, p. 214 refers to "modern historians" who criticize Bragg for ordering 11 to 14 assaults, but Daniel accounts for only 8 unique instances.

- Historians disagree on the number of artillery pieces the Confederates massed against the Hornets Nest. Cunningham 2007, p. 290 accounts for 51; Daniel 1997, p. 229 argues for 53; Sword 1992, p. 326 and Eicher 2001, p. 228 report the traditional count of 62, which was originally established by battlefield historian D. W. Reed.

- Sword 1992, p. 306 lists 2,320 captured; Eicher 2001, p. 228: lists 2,200; Daniel 1997, p. 214: lists 2,400.

- In 1837, Johnston had been hit in the right hip by a pistol shot during a duel that severed the sciatic nerve. This earlier injury caused nerve damage and numbness in his right leg. As a result, Johnston was unable to feel heat, cold, or pain in his right leg and may not have realized that he had been seriously wounded at Shiloh. See Allen 1997a, p. 53

- A traditional view of the battle holds that Johnston's death caused a lull in fighting, which deprived the Confederates of their momentum and eventually led to their defeat in battle. Both Sword 1992, p. 310 and Daniel 1997, p. 235 subscribe to this view; however, Cunningham 2007, pp. 277–78, maintains that any such lull was a factor of the general Confederate disorganization, not Beauregard's lack of action, and that he held a good sense of the dispositions on the battlefield.

- Cunningham 2007, p. 321 estimates the number of stragglers and noncombatant troops at the landing to be about 15,000.

- As with the Hornets Nest, the estimate of the number of guns varies widely. Grant, in his memoirs, recalls "20 or more." Daniel 1997, p. 246 and Grimsley & Woodworth 2006, p. 109 account for 41 guns; Sword 1992, p. 356 states there were "at least 10 batteries"; and [90] cites historical accounts that vary from 42 to more than 100.

- Cunningham 2007, pp. 332–34: Prentiss laughed to his captors, "You gentlemen have had your way today, but it will be very different to-morrow. You'll see! Buell will effect the junction with Grant to-night, and we'll turn the tables on you in the morning."

- In Steven E. Woodworth's Sherman: Lessons in Leadership, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, ISBN 978-0-230-61024-8, p. 57, he wrote (without a citation) that Sherman recalled in later years that the gunfire there was the heaviest he heard during the war.

- A popular story about Forrest's grabbing a Union soldier by the collar and lifting him up on the horse to be a human shield is probably not true; none of the cited references (Sword 1992, pp. 425–26; Daniel 1997, pp. 296–97; Cunningham 2007, pp. 373–75) include it.

- Some authors, including Larry J. Daniel and Jean Edward Smith, claim that the total of 23,746 casualties at the battle (counting both sides) represented more than the American battle-related casualties of the American Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican–American War combined. See Smith 2001, p. 204 and Daniel 1997, p. 305. Timothy B. Smith disputes this claim as untrue.[125]

- In his memoirs, Grant (vol. 1, chap. 25, p. 22) disputes the Confederate casualties reported by Beauregard, claiming that the Union burial parties documented far more Confederate dead than Beauregard's figures. Grant estimates the Confederate dead at 4,000.

- Daniel 1997, p. 305 and Smith 2001, p. 204: The battles were First Bull Run, Wilson's Creek, Fort Donelson, and Pea Ridge.

References

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Part 1, pp. 100–05

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Part 1, pp. 105–08

- Eicher 2001, p. 222.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Part 1, pp. 382–84

- Stephens 2010, pp. 80, 90–93.

- Further information: Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Part 1, p. 112.

- 48,894 according to Eicher 2001, p. 222.

- 17,918 Eicher 2001, p. 223.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Part 1, p. 396

- 44,699 according to Eicher 2001, p. 222

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Part 1, p. 108

- Cunningham 2007, pp. 422–24.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Part 1, p. 395

- Cunningham 2007, p. 422.

- Smith 2014, pp. 2–4.

- Smith 2014, pp. 6–7.

- Allen 1997a, pp. 7–8.

- Stephens 2010, p. 64.

- Conger 1970, p. 211; Nevin 1983, p. 104; Woodworth 2005, pp. 128–31, 141–42; Cunningham 2007, pp. 72–74; Smith 2001, pp. 173–179.

- Allen 1997a, p. 12.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 64, 68.

- Allen 1997a, p. 13.

- Marszalek 2004, pp. 119–121; Smith 2001, p. 179; Woodworth 2005, p. 136.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume X, Part 1, p. 112

- Smith 2001, p. 185.

- Eicher 2001, p. 223.

- Smith 2014, pp. 51–55.

- Grant, pp. 211–12.

- Daniel 1997, p. 139; Nevin 1983, p. 105; Stephens 2010, p. 65.

- Eicher 2001, pp. 222, 230; Grant, Memoirs, p. 245 (Lib. of Am. ed.).

- McDonough 1977, p. 25.

- Cunningham 2007, pp. 93, 98–101, 120.

- Cunningham 2007, p. 125.

- "The Road to Shiloh, April 1862 – The Civil War For Dummies". erenow.com.

- Carlson, Joseph R. The Negative Impact of Jefferson Davis' Lack of Grand Strategy (Master's). American Military University. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- "Battle of Shiloh: Shattering Myths".

- "The Battle of Shiloh".

- Daniel 1997, pp. 119, 121–23; Cunningham 2007, pp. 128–29, 137–40; Woodworth 2005, p. 108; Eicher 2001, p. 223.

- Allen 1997a, p. 19.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 127–28; Stephens 2010, p. 78.

- Stephens 2010, p. 78.

- "Battle of Shiloh: Shattering Myths".

- Allen 1997a, p. 24.

- Smith 2001, p. 185; McPherson 1988, p. 408; Woodworth 2005, pp. 150–54; Nevin 1983, pp. 110–11; Cunningham 2007, pp. 143–44; Sword 1992, p. 127; Eicher 2001, p. 224; Daniel 1997, pp. 141–42.

- "Great American History Unsung Hero of the Civil War".

- Stephens 2010, p. 79.

- Smith 2014, pp. 126, 199.

- Cunningham 2007, p. 140.

- Nevin 1983, p. 113; Daniel 1997, p. 145.

- Allen 1997a, p. 20; Cunningham 2007, p. 200.

- Smith 2014, p. 151.

- Smith 2001, p. 187; Esposito 1959: Map 34; Eicher 2001, pp. 224–26

- McPherson 1988, p. 409.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 143–64; Eicher 2001, p. 226; Esposito 1959: Map 34.

- "Concise History of the 7th Arkansas Infantry, Company I". Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- Smith 2014, pp. 128–30.

- Daniel 1997, p. 139; Cunningham 2007, p. 133.

- Stephens 2010, p. 83.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 79, 91.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 143–64; Woodworth 2005, pp. 164–66; Cunningham 2007, pp. 157–58, 174; Eicher 2001.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 83–84; Allen 1997b, p. 8.

- Allen 1997b, pp. 8–9.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 85, 92.

- Allen 1997b, pp. 9–10.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 86–88.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 88–89.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 88-89; Allen 1997b, p. 10.

- Woodworth 2001, p. 77; Cunningham 2007, p. 339.

- Allen 1997b, p. 10.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 88-89.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 80, 90–91.

- Woodworth 2001, pp. 72–82; Daniel 1997, pp. 256–61; Sword 1992, pp. 439–40; Cunningham 2007, pp. 338–39; Smith 2001, p. 196.

- Ray Boomhower (Winter 1993). "The Gen. Lew Wallace Study and Ben-Hur Museum". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. 5 (1): 14.

- Cunningham 2007, pp. 241–42.

- Cunningham 2007, p. 298.

- "The Hornet's Nest" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- Nevin 1983, pp. 121–29, 136–39; Esposito 1959: Map 36; Daniel 1997, pp. 207–14; Woodworth 2005, pp. 179–85; Eicher 2001, p. 227

- "Shiloh Battlefield Tours – 1 Death of General Johnston Frame". civilwarlandscapes.org (cwla). Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 226–27; Allen 1997a, p. 53.

- Smith 2014, pp. 191–92.

- "Tennessee 4 Me – General Albert Sidney Johnston's death at Shiloh". www.tn4me.org.

- "cwla – Shiloh Battlefield Tours – 1 Death of General Johnston Frame". civilwarlandscapes.org. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- Cunningham 2007, pp. 275–77; Sword 1992, pp. 271–73, 443–46.

- Allen 1997a, p. 53.

- Nevin 1983, pp. 121–29, 136.

- Smith 2014, pp. 218, 223.

- Eicher 2001, pp. 227–28; Daniel 1997, pp. 235–237; Nevin 1983, pp. 138–39.

- Smith 2014, pp. 209–11.

- Cunningham 2007, p. 317.

- Cunningham 2007, p. 307.

- Daniel 1997, p. 265.

- Cunningham 2007, pp. 323–26.

- Allen 1997a, p. 61.

- Grant, Ulysses S (1894). Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. New York: Charles L. Webster & Company. p. 206.

- Smith 2001, p. 201; Sword 1992, pp. 369–82; Allen 1997b, p. 7.

- Cunningham 2007, p. 333.

- Allen 1997b, p. 13.

- Cunningham 2007, pp. 340–41.

- "Civil War Landscapes Association". Civilwarlandscapes.org. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- Nevin 1983, p. 147; Daniel 1997, pp. 252–56; Cunningham 2007, pp. 323–26, 332; Sword 1992, p. 378.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 263-264, 278.

- Stephens 2010, pp. 93, 95; Allen 1997b, p. 16.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 265, 278.

- Woodworth 2005, p. 196.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 275–283.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 283–87.

- "PERSONAL MEMOIRS U. S. GRANT, COMPLETE". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- Allen 1997b, p. 46; Stephens 2010, p. 101.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 289–92.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 296–97; Sword 1992, pp. 423–24.

- Allen 1997b, p. 48.

- Sword 1992, pp. 425–26; Daniel 1997, pp. 296–97; Cunningham 2007, pp. 373–75.

- Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, Chapter XXV

- Daniel 1997, p. 308.

- Smith 2001, pp. 204–205; Woodworth 2005, pp. 198–201; Cunningham 2007, pp. 382–83.

- Smith 2001, pp. 204–205.

- Woodworth 2005, pp. 198–201; Cunningham 2007, pp. 382–83.

- "Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, Struck by a bullet-precipitate retreat of the Confederates – intrenchments at Shiloh – General Buell–General Johnston – remarks on Shiloh". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- Daniel 1997, p. 309.

- Smith 2014, p. 392.

- O'Connell 2014, p. 147.

- Cunningham 2007, pp. 384–96.

- Gudmens 2005, pp. 84–85.

- Smith 2014, p. 402.

- Eicher 2001, p. 230; Cunningham 2007, pp. 421–24.

- Smith 2014, p. 122.

- Smith 2014, p. 344.

- Simon 2000, p. v.

- McDonough 2000, p. 1775.

- Smith 2014, p. 409.

- Daniel 1997, pp. 316–17.

- Smith 2014, pp. 418–19.

- Smith 2014, pp. 420–21.

- ""A History of Shiloh National Military Park," Charles E. Shedd, Jr., 1954" (PDF).

- American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- "The Battle of Shiloh Summary & Facts". Civilwar.org. Archived from the original on September 8, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- "Maps of Shiloh, Tennessee (1862): Battle of Shiloh – April 6, 1862". Civil War Trust. Archived from the original on August 22, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- "1962 Civil War Centennial Issue". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

Sources

- Allen, Stacy D. (February 1997a). "Shiloh!: The Campaign and First Day's Battle". Blue & Gray. Columbus, Ohio: Blue and Gray Enterprises, Inc. XIV (3): 7–8.

- Allen, Stacy D. (April 1997b). "Shiloh!: The Second Day's Battle and Aftermath". Blue & Gray. Columbus, Ohio: Blue and Gray Enterprises, Inc. XIV (4): 7–8.

- Conger, Arthur Latham (1970) [1931]. The Rise of U.S. Grant. Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, first published by the Century Co. ISBN 978-0-8369-5572-9.

- Cunningham, O. Edward (2007). Joiner, Gary; Smith, Timothy (eds.). Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862. New York, New York: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-27-2.

- Daniel, Larry J. (1997). Shiloh: The Battle That Changed the Civil War. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80375-3.

- Eicher, David J. (2001). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-84944-7.

- Esposito, Vincent J (1959). West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York, New York: Frederick A. Praeger. OCLC 5890637.

- Grimsley, Mark; Woodworth, Steven E. (2006). Shiloh: A Battlefield Guide. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7100-5.

- Gudmens, Jeffrey J. (2005). Staff Ride Handbook for the Battle of Shiloh, 6–7 April 1862. Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-4289-1012-6.

- Hanson, Victor Davis (2003). Ripples of Battle: How Wars of the Past Still Determine How We Fight, How We Live, and How We Think. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-50400-3.

- McDonough, James Lee (1977). Shiloh: In Hell before Night. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-232-7.

- McDonough, James Lee (2000). Heidler, David S.; Heidler, Jeanne T. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History: Battle of Shiloh. New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04758-5.

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7.

- Marszalek, John F. (2004). Commander of All Lincoln's Armies: A Life of General Henry W. Halleck. Boston, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01493-0.

- Nevin, David (1983). The Editors of Time-Life Books (ed.). The Road to Shiloh: Early Battles in the West. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8094-4712-1.

- O'Connell, Robert L. (2014). Fierce Patriot: The Tangled Lives of William Tecumseh Sherman. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-679-60469-3.

- Simon, John Y. (2000). "Foreword". Life and Letters of General W. H. L. Wallace. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-2347-0.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-84927-0.

- Smith, Timothy B. (2014). Shiloh: Conquer or Perish. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1995-5.

- Stephens, Gail (2010). The Shadow of Shiloh: Major General Lew Wallace in the Civil War. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87195-287-5.

- Sword, Wiley (1992) [1974]. Shiloh: Bloody April. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, First published by Morrow. ISBN 978-0-7006-0650-4.

- Woodworth, Steven E., ed. (2001). Grant's Lieutenants: From Cairo to Vicksburg. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1127-0.

- Woodworth, Steven E., ed. (2005). Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41218-9.

- "Grant at Shiloh: A letter of William Rowley". The Ulysses S. Grant Association Newsletter. Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library / Ulysses S. Grant Association. X1. 1972–1973. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016.

Further reading

- Arnold, James R., Carl Smith, and Alan Perry. Shiloh 1862: The Death of Innocence. London: Osprey Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-85532-606-X.

- Davis, William C., ed. (1990). "Chapter 2: This Day Will Long Be Remembered: Shiloh". Diary of a Confederate Soldier: John S. Jackman of the Orphan Brigade. American Military History. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 28–42. ISBN 0-87249-695-3. LCCN 90012431. OCLC 906557161.

- Frank, Joseph Allan, and George A. Reaves. Seeing the Elephant: Raw Recruits at the Battle of Shiloh. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003. ISBN 0-252-07126-3. First published 1989 by Greenwood Press.

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. 2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- Groom, Winston. Shiloh, 1862. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4262-0874-4.

- Groom, Winston. "Why Shiloh Matters." New York Times Opinionator weblog, April 6, 2012.

- Gudmens, Jeffrey J. Staff Ride Handbook for the Battle of Shiloh, 6–7 April 1862. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2005. OCLC 58801939.

- Howard, Samuel Meek (1921). The illustrated comprehensive history of the great battle of Shiloh. Gettysburg, S.D. : Howard.

- Martin, David G. The Shiloh Campaign: March–April 1862. New York: Da Capo Press, 2003. ISBN 0-306-81259-2.

- Mertz, Gregory A. Attack at Daylight and Whip Them: The Battle of Shiloh, April 6–7, 1862. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2019. ISBN 978-1-61121-313-3.

- Reed, David W. The Battle of Shiloh and the Organizations Engaged. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1909.

- Smith, Timothy B. Rethinking Shiloh: Myth and Memory. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1-57233-941-5.

- —— The Untold Story of Shiloh: The Battle and the Battlefield. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57233-466-3.

- Woodworth, Steven E.., ed. The Shiloh Campaign. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8093-2892-5.

- Tidball, John C. The Artillery Service in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865. Westholme Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1594161490.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

External links

- Report of Major General U.S. Grant on the Battle of Shiloh

- Battle of Shiloh: Maps, histories, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- Battle of Shiloh Animated Map (Civil War Trust)

- U.S. National Park Service site for Shiloh National Military Park

- Civilwarhome description of the battle

- Animated history of the Battle of Shiloh

- Newspaper coverage of the Battle of Shiloh

- New York Times main page headline, April 7, 1862, The Battle of Pittsburgh

- C-SPAN American History TV Battle of Shiloh Tour

- C-SPAN American History TV tour of Shiloh National Military Park Visitor Center artifacts

- A sober look at the battle of Shiloh

- Pittsburg Landing : or, Adventures of a young volunteer : a thrilling story of a western boy / by Duke Duncan from Digital Library@Villanova University

.jpg)