Greeneville, Tennessee

Greeneville is a town in and the county seat of Greene County, Tennessee, United States.[11] The population as of the 2010 census was 15,062. The town was named in honor of Revolutionary War hero Nathanael Greene.[4] It is the only town with this spelling in the United States, although there are numerous U.S. towns named Greenville.[4] The town was the capital of the short-lived State of Franklin in the 18th-century history of East Tennessee.[12]

Greeneville, Tennessee | |

|---|---|

| Town of Greeneville | |

Corner of Main and Depot in downtown Greeneville | |

Logo | |

| Nickname(s): Home of President Andrew Johnson[1] | |

Location of Greeneville in Greene County, Tennessee. | |

| Coordinates: 36°10′6″N 82°49′21″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Tennessee |

| County | Greene |

| Founded | 1783[2] |

| Incorporated | 1795[3] |

| Named for | Nathanael Greene[4] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Aldermen-administrator |

| • Mayor | W.T. Daniels |

| • Town Administrator | Todd Smith |

| • Town Recorder | Carolyn Susong |

| • Chief of Police | Timothy P. Ward |

| • Aldermen | List of Aldermen

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 17.00 sq mi (44.02 km2) |

| • Land | 17.00 sq mi (44.02 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,519 ft (463 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 15,062 |

| • Estimate (2019)[8] | 14,891 |

| • Density | 876.10/sq mi (338.26/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 37616, 37743 & 37745 (General Delivery) and 37744 (P.O. Boxes) |

| Area code(s) | 423 |

| FIPS code | 47-30980[9] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1286186[10] |

| Website | http://www.greenevilletn.gov |

Greeneville is known as the town where United States President Andrew Johnson began his political career when elected from his trade as a tailor. He and his family lived there most of his adult years. It was an area of strong abolitionist and Unionist views and yeoman farmers, an environment which influenced Johnson's outlook.[13]

The Greeneville Historic District was established in 1974.[14]

The U.S. Navy Los Angeles-class submarine USS Greeneville was named in honor of the town.[15]

Greeneville is part of the Johnson City-Kingsport- Bristol TN-VA Combined Statistical Area – commonly known as the "Tri-Cities" region.

Geography

Greeneville is located at 36°10′6″N 82°49′21″W (36.168240, -82.822474).[16] It lies in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. These hills are part of the Appalachian Ridge-and-Valley Province, which is characterized by fertile river valleys flanked by narrow, elongate ridges. Greeneville is located roughly halfway between Bays Mountain to the northwest and the Bald Mountains— part of the main Appalachian crest— to the southeast. The valley in which Greeneville is situated is part of the watershed of the Nolichucky River, which passes a few miles south of the town.

Several federal and state highways now intersect in Greeneville, as they were built to follow old roads and trails. U.S. Route 321 follows Main Street through the center of the town and connects Greeneville to Newport to the southwest. U.S. Route 11E (Andrew Johnson Highway), which connects Greeneville with Morristown to the west, intersects U.S. 321 in Greeneville and the merged highway proceeds northeast to Johnson City. Tennessee State Route 107, which also follows Main Street and Andrew Johnson Hwy, Greeneville to Erwin to the east and to the Del Rio area to the south. Tennessee State Route 70 (Lonesome Pine Trail) connects Greeneville with Interstate 81, and Rogersville to the north and Asheville, North Carolina to the south. Tennessee State Route 172 (Baileyton Road) connects Greeneville with Interstate 81 and Baileyton to the north.

Tennessee State Route 93 (Kingsport Highway) connects Greeneville to Interstate 81, Fall Branch and Kingsport to the north.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 17.01 square miles (44.1 km2), all land.

Climate

| Climate data for Greeneville, Tennessee | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F | 47 | 52 | 61 | 69 | 78 | 85 | 88 | 87 | 82 | 72 | 61 | 50 | 69 |

| Average low °F | 24 | 28 | 33 | 41 | 51 | 60 | 64 | 63 | 55 | 43 | 34 | 27 | 44 |

| Average precipitation inches | 3.15 | 3.66 | 3.43 | 3.86 | 4.06 | 4.09 | 4.69 | 4.29 | 3.23 | 2.09 | 2.83 | 3.35 | 42.73 |

| Average high °C | 8 | 11 | 16 | 21 | 26 | 29 | 31 | 31 | 28 | 22 | 16 | 10 | 21 |

| Average low °C | −4 | −2 | 1 | 5 | 11 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 13 | 6 | 1 | −3 | 7 |

| Average precipitation mm | 80 | 93 | 87 | 98 | 103 | 104 | 119 | 109 | 82 | 53 | 72 | 85 | 1,085 |

| Source: US Climate Data[17] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods

- Buckingham Heights

- Cherrydale

- Oak Hills

- Windy Hills

- Harrison Hills

History

Early history

Native Americans were hunting and camping in the Nolichucky Valley as early as the Paleo-Indian period (c. 10,000 B.C.). A substantial Woodland period (1000 B.C. - 1000 A.D.) village existed at the Nolichucky's confluence with Big Limestone Creek (now part of Davy Crockett Birthplace State Park).[18] By the time the first Euro-American settlers arrived in the area in the late 18th century, the Cherokee claimed the valley as part of their hunting grounds. The Great Indian Warpath passed just northwest of modern Greeneville, and the townsite is believed to have once been the juncture of two lesser Native American trails.[19]

Permanent European settlement of Greene County began in 1772. Jacob Brown, a North Carolina merchant, leased a large stretch of land from the Cherokee, located between the upper Lick Creek watershed and the Nolichucky River, in what is now the northeastern corner of the county. The "Nolichucky Settlement" initially aligned itself with the Watauga Association as part of Washington County, North Carolina. After voting irregularities in a local election, however, an early Nolichucky settler named Daniel Kennedy (1750–1802) led a movement to form a separate county, which was granted in 1783.

The county was named after Nathanael Greene, reflecting the loyalties of the numerous Revolutionary War veterans who settled in the Nolichucky Valley, especially from Pennsylvania and Virginia. The first county court sessions were held at the home of Robert Kerr, who lived at "Big Spring" (near the center of modern Greeneville). Kerr donated 50 acres (0.20 km2) for the establishment of the county seat, most of which was located in the area currently bounded by Irish, College, Church, and Summer streets. "Greeneville" was officially recognized as a town in 1786.[20]

Greeneville becomes capital of the State of Franklin

In 1784, North Carolina attempted to resolve its debts by giving the U.S. Congress its lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, including Greene County, abandoning responsibility for the area to the federal government. In response, delegates from Greene and neighboring counties convened at Jonesborough and resolved to break away from North Carolina and establish an independent state. The delegates agreed to meet again later that year to form a constitution, which was rejected when presented to the general delegation in December.[21] Reverend Samuel Houston (not to be confused with the later governor of Tennessee and Texas) had presented a draft constitution which restricted the election of lawyers and other professionals. Houston's draft met staunch opposition, especially from Reverend Hezekiah Balch (1741–1810) (who was later instrumental in the creation of Tusculum College). John Sevier was elected governor, and other executive offices were filled.

A petition for statehood for what would have become known as the State of Franklin (named in honor of Benjamin Franklin) was drawn at the delegates session in May 1785. The delegates submitted a petition for statehood to Congress, which failed to gain the requisite votes needed for admission to the Union. The first state legislature of Franklin met in December 1785 in a crude log courthouse in Greeneville, which had been named the capital city the previous August.[22] During this session, the delegates finally approved a constitution which was based on, and quite similar to, the North Carolina state constitution. However, the Franklin movement began to collapse soon thereafter, with North Carolina reasserting its control of the area the following spring.

In 1897, at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition in Nashville, a log house that had been moved from Greeneville was displayed as the capitol where the State of Franklin's delegates met in the 1780s. There is, however, nothing to verify that this building was the actual capitol. In the 1960s, the capitol was reconstructed, based largely on the dimensions given in historian J. G. M. Ramsey's Annals of Tennessee.[23]

Greeneville and the abolitionist movement

Greene County, like much of East Tennessee, was home to a strong abolitionist movement in the early 19th century. This movement was likely influenced by the relatively large numbers of Quakers who migrated to the region from Pennsylvania in the 1790s. The Quakers considered slavery to be in violation of Biblical Scripture, and were active in the region's abolitionist movement throughout the antebellum period.[24] One such Quaker was Elihu Embree (1782–1820), who published the nation's first abolitionlist newspaper, The Emancipator, at nearby Jonesborough.

When Embree's untimely death in 1820 effectively ended publication of The Emancipator, several of Embree's supporters turned to Ohio abolitionist Benjamin Lundy, who had started publication of his own antislavery newspaper, The Genius of Universal Emancipation, in 1821. Anticipating that a southern-based abolitionist movement would be more effective, Lundy purchased Embree's printing press and moved to Greeneville in 1822. Lundy remained in Greeneville for two years before moving to Baltimore. He would later prove influential in the career of William Lloyd Garrison, whom he hired as an associate editor in 1829.[25][26]

Greenevillians involved in the abolitionist movement included Hezekiah Balch, who freed his slaves at the Greene County Courthouse in 1807. Samuel Doak, the founder of Tusculum College, followed in 1818. Valentine Sevier (1780–1854), a nephew of John Sevier who served as Greene County Court Clerk, freed his slaves in the 1830s and offered to pay for their passage to Liberia, which had been formed as a colony for freed slaves. Francis McCorkle, the pastor of Greeneville's Presbyterian Church, was a leading member of the Manumission Society of Tennessee.[27]

Civil War

In June 1861, on the eve of the Civil War, thirty counties of the pro-Union East Tennessee Convention met in Greeneville to discuss strategy after state voters had elected to join the Confederate States of America. The convention sought to create a separate state in East Tennessee that would remain with the United States. The state government in Nashville rejected the convention's request, however, and East Tennessee was occupied by Confederate forces shortly thereafter.[28] Thomas Dickens Arnold, a Greeneville resident and former congressman who attended the convention, advocated the use of violent force to allow East Tennessee to break away from Tennessee, and taunted other members of the convention who advocated a more peaceful set of resolutions.[29]

Several conspirators involved in the pro-Union East Tennessee bridge burnings lived near what is now Mosheim, and managed to destroy the railroad bridge over Lick Creek in western Greene County on the night of November 8, 1861. Two of the conspirators, Jacob Hensie and Henry Fry, were executed in Greeneville on November 30, 1861.[30]

A portion of James Longstreet's army wintered in Greeneville following the failed Siege of Knoxville in late 1863.[31] Confederate general John Hunt Morgan was killed in Greeneville during a raid by Union soldiers led by Alvan Cullem Gillem on September 4, 1864.[32]

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson, the 17th President of the United States, spent much of his active life in Greeneville. In 1826, Johnson arrived in Greeneville after fleeing an apprenticeship in Raleigh. Johnson chose to remain in Greeneville after learning that the town's tailor was planning to retire. Johnson purchased the tailor shop, which he moved from Main Street to its present location at the corner of Depot and College streets. Johnson married a local girl, Eliza McCardle, in 1827. The two were married by Mordecai Lincoln (1778–1851), who was Greene County's Justice of the Peace. He was a cousin of Abraham Lincoln, under whom Johnson would serve as Vice President.[33][34]

In the late 1820s, a local artisan named Blackstone McDannel often stopped by Johnson's tailor shop to debate issues of the day, especially the Indian Removal, which Johnson opposed. Johnson and McDannel decided to debate the issue publicly. The interest sparked by this debate led Johnson, McDannel, and several others to form a local debate society. The experience and influence Johnson gained in debating local issues helped him get elected to the Greeneville City Council in 1829. He was elected mayor of Greeneville in 1834, although he resigned after just a few months in office to pursue a position in the Tennessee state legislature, which he attained the following year. As Johnson rose through the ranks of political office in state and national government, he used his influence to help Greeneville constituents obtain government positions, among them his long-time supporter, Sam Milligan, who was appointed to the Court of Claims in Washington, D.C.[35]

Whilst Andrew Johnson was away from home, during his vice-presidency, both Union and Confederate armies often used his home as a place to stay and rest during their travel. Soldiers left graffiti on the walls of Johnson's home. Confederate soldiers left notes on the walls expressing their displeasure, to put it delicately, of Johnson. Evidence of this can still be seen at the Andrew Johnson home. Andrew Johnson had to almost completely renovate his home after he returned home from Washington D.C.

The Andrew Johnson National Historic Site, located in Greeneville, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1963. Contributing properties include Johnson's tailor shop at the corner of Depot Street and College Street. The site also maintains Johnson's house on Main Street and the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery (atop Monument Hill to the south). A replica of Johnson's birth home and a life-size statue of Johnson have been placed across the street from the visitor center and tailor shop.[36]

2011 tornado outbreak

The rural community of Camp Creek south of Greeneville was severely affected by an EF-3 tornado in 2011 Super Outbreak.[37] Six people were killed immediately and a seventh died later.[38][39] Horse Creek, southeast of Greeneville, was also hit by an EF-3 tornado during the same outbreak.[40] One person was killed in that community.[41] A total of eight were killed in Greene County..

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 660 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,039 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,066 | 2.6% | |

| 1890 | 1,779 | 66.9% | |

| 1900 | 1,817 | 2.1% | |

| 1910 | 1,920 | 5.7% | |

| 1920 | 3,775 | 96.6% | |

| 1930 | 5,544 | 46.9% | |

| 1940 | 6,784 | 22.4% | |

| 1950 | 8,721 | 28.6% | |

| 1960 | 11,759 | 34.8% | |

| 1970 | 13,722 | 16.7% | |

| 1980 | 14,097 | 2.7% | |

| 1990 | 13,532 | −4.0% | |

| 2000 | 15,198 | 12.3% | |

| 2010 | 15,062 | −0.9% | |

| Est. 2019 | 14,891 | [8] | −1.1% |

| Sources:[42][43] | |||

As of the 2010 census, there were 15,062 people; 6,478 households; 7,399 housing units; and 3,845 families in the town.[44][note 1] The population density was 885.3 per square mile (341.8/km2).[45] The racial makeup of the city was 89.1% White, 5.6% African American, 0.2% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 2.3% from other races, and 2% from two or more races.[44][note 2] Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 4.4% of the population.[44][note 3]

There were 6,506 households out of which 24.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.2% were married couples living together, 14.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.6% were non-families. 36.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 17.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.2 and the average family size was 2.86.

The age distribution was 21.2% under 18 and 21% who were 65 or older. The median age was 42.6 years. The median income for a household in the city was $51,692. The per capita income for the city was $24,376. About 13.9% of the population was below the poverty line.[46]

Economy

Retail is a major employer in Greeneville. The largest shopping center in Greeneville is Greeneville Commons, which includes Hobby Lobby, Ross, Five Below, Marshall's, Belk, Burke's Outlet and Hibbett Sports. Grocery stores in Greeneville include three K-VA-T Food City Supermarkets, two Ingles Markets, Dollar General Market, Sav-Mor Foods (a Grocery Store owned by Ingles Markets), Publix and Save-A-Lot. Walmart and Lowe's also have stores in Greeneville.

Arts and culture

Festivals and fairs

The Greene County Fair is recognized statewide as one of the best of its size. In 2005, it received the Tennessee Association of Fairs highest award, the “Champion of Champions” fair trophy. In 2001 and 2004, it was named the AAA division Champion Fair in the state of Tennessee. In 1994 and 2000, it was named first runner-up for the Champion Fair in the AAA Division, and in 1988, received the award for Most Outstanding Fair in Tennessee.

There has been a fair in some form in Greene County since 1870 when the Farmers and Mechanics Association held its first exposition. The present-day Greene County Fair Association was incorporated in 1949. The Fair exists on the support of countless volunteers, board members and officers since 1949. The fair holds many various events such as the "Fairest of the Fair" event, in which different young ladies are crowned based on voluntary activities and their performance in the pageant.

The fair was also an inspiration for The Band Perry's song "Walk Me Down The Middle", which was featured on their eponymous debut album.

Sports

Greeneville is home to the Greeneville Reds, a Minor League Baseball team of the Appalachian League, which began play in 2018.[47] The team plays at Pioneer Park on the campus of Tusculum College.[48]

Two other minor league teams have hailed from Greeneville. The Greeneville Burley Cubs played in the Appalachian League from 1921 to 1925 and 1938 to 1942.[48] They won the league championship in 1925 and 1928.[49] From 2004 to 2017, Greeneville was represented in the Appalachian League by the Greeneville Astros.[48] They won the Appalachian League championship in 2004 and 2015.[49]

Parks and recreation

Town of Greeneville Parks and Recreation Department maintains:

- Dogwood Park

- Ginny Kidwell Amphitheater at Dogwood Park

- Hardin Park

- Highland Hills Park

- J.J. Jones Memorial Park

- Kinser Park[50] (Kinser Park is Co-owned by the Town of Greeneville and Greene County)

- Veterans Memorial Park (Forest Park)

- Wesley Heights Park

Government

Municipal

Greeneville is administered through a Mayor-Alderman-Administrator form of government. The town has a mayor and four alderman, along with the town administrator who is the chief administrative officer and is in charge of supervising all town employees and is required to develop an annual budget and present it to the mayor and aldermen. The following is a list of current officials as of October 2017:

- W.T. Daniels – Mayor

- "Buddy" Hawk – Alderman

- Scott Bullington – Alderman

- Keith Paxton – Alderman

- Jeff Taylor – Alderman

- Todd Smith – City/Town Administrator[51]

- Amy Rose – Public Relations Manager

- Tim Ward – Chief of Police

- Carolyn C. Susong – Town Recorder

- Brooke Davis – Town Accountant

- Alan Shipley – Chief of Fire Department

- Harold "Butch" Patterson – Director of Parks and Recreation

- Brad Peters – Director of Public Works Department

State

Greeneville is represented in the Tennessee House of Representatives in the 5th district,[52] by Representative David Hawk, a Republican.[53]

In the Tennessee State Senate, Greeneville is represented by the 1st district,[54] by Senator Steve Southerland, also a Republican.[55]

Federal

Greeneville is represented in the United States House of Representatives by Republican Phil Roe of the 1st congressional district.[56]

Education

Greeneville is home to Walters State Niswonger Campus, which is currently being expanded.[57][58]

Tusculum University is located in nearby Tusculum.

The Town of Greeneville City Schools operates:

- Eastview Elementary School - Grades PK-5

- Greene Technology Center - Grades 9-12 (Also contains adult education classes and is associated with the Tennessee College of Applied Technology at Morristown)

- Greeneville High School - Grades 9-12

- Greeneville Middle School - Grades 6-8

- Hal Henard Elementary School - Grades PK-5

- Highland Elementary School - Grades PK-5

- Tusculum View Elementary School - Grades PK-5

Media

Television

Greeneville is part of both the Knoxville DMA and the Tri-Cities DMA. One station has Greeneville listed as its city of license (WEMT-Fox Tri-Cities). WGRV (AM) also has a television station on Comcast Cable channel 18. The channel simulcasts WGRV's live newscasts and other live programs and shows local events.

Radio

Greeneville has three radio stations: WGRV (AM), WIKQ-FM, and WSMG-AM.

Newspaper

The Greeneville and Greene County area are served by The Greeneville Sun, a daily newspaper published Monday through Saturday.[59] The Greeneville Sun also publishes a free newspaper, The Greeneville Neighbor News, which spotlights arts and entertainment.

Infrastructure

Healthcare

Greeneville has two hospitals, both of which are part of Ballad Health.[60]

- Greeneville Community Hospital East, formerly Laughlin Memorial Hospital[61][62]

- Greeneville Community Hospital West, formerly Takoma Regional Hospital[61][62]

Greeneville also has many nursing facilities, including Life Care Center of Greeneville, Laughlin Healthcare Center, Signature HEALTHCARE of Greeneville, Morning Pointe, Wellington Place owned by Brookdale Senior Living, Maxim Healthcare Services and Comcare.

Notable people

- Dale Alexander: professional baseball player, 1932 American League batting champion.

- Thomas D. Arnold, congressman and foe of Andrew Jackson.

- Elias Nelson Conway, fifth governor of Arkansas.

- William Crutchfield (1824–1890): Congressman and Southern Unionist.

- Samuel Doak (1749–1830) Presbyterian minister, pioneer, founded earliest schools and churches in East Tennessee. President of Washington College 1795-1818, he moved to Greeneville and taught at Tusculum Academy, later Tusculum College from 1818-1830. Delegate to the "Lost State" of Franklin which convened in Greeneville.[63]

- Col. Joseph Hardin (1734–1801) Speaker of the House for the State of Franklin; trustee of Greeneville (now Tusculum) College.[64]

- Andrew Johnson: Alderman and Mayor of Greeneville, Tennessee. U.S. Senator, U.S. Vice President, U.S. President.[65]

- Sergeant Elbert Kinser: (October 21, 1922 - May 4, 1945) was a United States Marine who received the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions and sacrifice of his life on Okinawa during World War II. US Marine Base Camp Kinser located on the island of Okinawa is named for Sgt Kinser.

- Frank Little (tenor), opera singer.

- Samuel Milligan (1814–1874), judge and state representative.

- Samuel R. Rodgers (1798–1866), Southern Unionist and post-Civil War Speaker of the Tennessee Senate.

- Oliver Perry Temple, 19th-century Knoxville attorney and economic promoter.

- Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, entrepreneur and founder of National Allied Publications, which would later evolve into DC Comics, was a Greeneville native and lived there for several years before his family moved away in his early childhood. Wheeler-Nicholson is widely credited as being the creator of the modern comic book.

- Park Overall, actress, most notably for Empty Nest, a Golden Girls spin-off.

- The Band Perry, musician siblings, Kimberly, Reid and Neil. Exceptionally talented, their modern take on country music attracts many new fans to the genre. Kimberlys unique vocal skills are widely recognised as being the best in the business.

Photo gallery

Andrew Johnson House on Main Street

Andrew Johnson House on Main Street Susong House, built c. 1795 by Valentine Sevier

Susong House, built c. 1795 by Valentine Sevier The Greeneville Sun, 121 W. Summer Street

The Greeneville Sun, 121 W. Summer Street Hotel Brumley, now General Morgan Inn & Conference Center, 111 North Main Street

Hotel Brumley, now General Morgan Inn & Conference Center, 111 North Main Street Cumberland Presbyterian Church, 201 North Main Street

Cumberland Presbyterian Church, 201 North Main Street St. James Episcopal Church, 105 North Church Street

St. James Episcopal Church, 105 North Church Street Valentine Sevier House, 214 North Main Street

Valentine Sevier House, 214 North Main Street Doughty House, 309 North Main Street

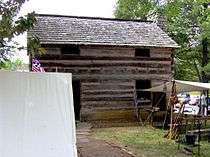

Doughty House, 309 North Main Street Antrium-log-cabin, 307 North Main Street

Antrium-log-cabin, 307 North Main Street Clawson Home, 204 South Main Street

Clawson Home, 204 South Main Street Lowry Snapp House, 216 West Irish Street

Lowry Snapp House, 216 West Irish Street Armitage-McKee Law Office, Corner of McKee and Irish Streets

Armitage-McKee Law Office, Corner of McKee and Irish Streets Dickson Williams Mansion, 106 North Irish Street

Dickson Williams Mansion, 106 North Irish Street

References

- Welcome signs at town's entrance.

- "Greeneville, Tennessee Visitor's Center". 27 February 2017. Greene Facts. Retrieved 30 Nov 2019.

- Tennessee Blue Book, 2005-2006, pp. 618-625.

- Miller, Larry (2001). Tennessee Place Names. Indiana University Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-253-33984-7. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "Greeneville". Municipal Technical Advisory Service. University of Tennessee. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "Town Government". Town of Greeneville. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Toomey, Michael (October 8, 2017). "State of Franklin". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Tennessee Historical Society. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- Bergeron, Paul (October 8, 2017). "Andrew Johnson". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Tennessee Historical Society. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "Greeneville Historic District". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "USS Greeneville (SSN 772)". NavySite. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Greeneville weather averages". US Climate Data.

- Samuel Smith, Historical Background and Archaeological Testing of the Davy Crockett Birthplace State Historic Area, Greene County, Tennessee (Nashville, Tenn.: Tennessee Division of Archaeology, 1980), 3.

- Richard Doughty, Greeneville: One Hundred Year Portrait (1775-1875) (Kingsport Press, 1974), 3.

- Doughty, 11-13.

- Doughty, 15-16.

- Doughty, 15-17.

- Doughty, 17-19.

- Doughty, 43.

- Tara Mitchell Mielnik, "Benjamin Lundy." The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2009. Retrieved: 11 February 2013.

- Doughty, 44-46.

- Doughty, 43-47.

- Eric Lacy, Vanquished Volunteers: East Tennessee Sectionalism from Statehood to Secession (Johnson City, Tenn.: East Tennessee State University Press, 1965), pp. 217-233.

- Oliver Perry Temple, East Tennessee and the Civil War (R. Clarke Company, 1899), p. 351.

- Temple, East Tennessee and the Civil War, p. 393.

- Blythe Semmer, "Greene County," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: 28 March 2014.

- A.B. Wilson, "Death of Morgan: Correction of Errors in Some Alleged Histories," The National Tribune, 24 April 1902, p. 7.

- Doughty, 59-60.

- Andrew Johnson National Historic Site - Curriculum Materials. Retrieved: 3 June 2008.

- Doughty, 59-73.

- "Learn About the Park". Andrew Johnson National Historic Site. National Park Service. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- Ken Little, "Fourth Tornado Confirmed: This One In Houston Valley Area," Archived 2012-07-08 at Archive.today Greeneville Sun May 13, 2011.

- "Six Greene County tornado victims identified," Tri-Cities.com, April 29, 2011, retrieved May 17, 2011.

- Ken Little, "7th Victim Dies From Injuries Related To Tornadoes," Archived 2012-07-11 at Archive.today Greeneville Sun May 5, 2011.

- "National Weather Service confirms eight tornadoes in our region," Archived 2011-10-08 at the Wayback Machine Tri-Cities.com, April 30, 2011.

- Ken Little, "'Incredible Devastation' Viewed By Sen. Corker," Archived 2012-07-10 at Archive.today Greeneville Sun May 7, 2011.

- "Census of Population and Housing: Decennial Censuses". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "2010 Census: General Population and Housing Characteristics". American FactFinder. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 30 Nov 2019.

- "Greeneville town, Tennessee". U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 30 Nov 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-08-15. Retrieved 2012-10-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Speddon, Zach (January 24, 2017). "Greeneville Reds to be Announced Friday". Ballpark Digest. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- "Greeneville, Tennessee Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 13, 2017.

- "Standings". 2017 Appalachian League Media Guide and Record Book. Minor League Baseball. pp. 39–61. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- Kinserpark.info. Retrieved: 7 May 2013.

- "Town of Greeneville". www.greenevilletn.gov.

- "State House District 05" (PDF). Tennessee House of Representative. Tennessee General Assembly. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- State of Tennessee. "Representative Rick Eldridge". www.capitol.tn.gov. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- "State Senate District 01" (PDF). Tennessee State Senate. Tennessee General Assembly. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- State of Tennessee. "Senator Steve Southerland". www.capitol.tn.gov. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- "Congressman Phil Roe Tennessee's 1st District – About the 1st District". Archived from the original on May 27, 2009.

- "Construction nears completion at Walters State downtown Greeneville campus". January 18, 2019.

- "Facilities Enhancement -- Campus Enhancement -- Walters State Community College". ws.edu.

- Greeneville Sun, official website. Retrieved: 29 October 2013.

- "Locations | Ballad Health". www.balladhealth.org.

- "Ballad spells out plan to consolidate hospital services in Greene County". February 8, 2019.

- Romano, Ellie (April 3, 2019). "Ballad Health rolls out changes to Greene County hospitals, residents express concern". WCYB.

- E. Alvin Gerhardt, Jr., "Samuel Doak." The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2009. Retrieved: 11 February 2013.

- Patterson, Prof. Tommie Cochran (1931). Joseph Hardin: A Biographical & Genealogical Study. Dissertation Manuscript. Library of the University of Texas at Austin, Texas; Austin, TX. OCLC 13179015.

- Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton. 1989.

Notes

- For total population, see field "Sex and Age>Total Population"; for households, see field "Households by type>Total households"; for housing unites, see field "Housing occupancy>Total housing units"; for families, see field "Households by type>Total households>Family households".

- All information from the Race section of the table.

- See section "Hispanic or Latino>Total population>Hispanic or Latino (of any race)".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Greeneville, Tennessee. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Greeneville. |