History of the Southern United States

The history of the Southern United States reaches back hundreds of years and includes the Mississippian people, well known for their mound building. European history in the region began in the very earliest days of the exploration and colonization of North America. Spain, France, and England eventually explored and claimed parts of what is now the Southern United States, and the cultural influences of each can still be seen in the region today. In the centuries since, the history of the Southern United States has recorded a large number of important events, including the American Revolution, the American Civil War, the ending of slavery, and the American Civil Rights Movement.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the United States |

|

|

By ethnicity |

|

|

Native American civilizations

In Pre-Columbian times, the only inhabitants of what is now the Southern United States were Native Americans. At the time of European contact much of the area was home to several regional variants of the Mississippian culture, an agrarian culture that flourished in the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States. The Mississippian way of life began to develop around the 10th century in the Mississippi River Valley (for which it is named).

Notable Native American nations that developed in the South after the Mississippians include what are known as "the Five Civilized Tribes": the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole.

European colonization

Spanish exploration

Spain made frequent exploratory trips to the New World after its discovery in 1492. Rumors of natives being decorated with gold and stories of a Fountain of Youth helped hold the interest of many Spanish explorers, and colonization eventually followed. Juan Ponce de León was the first European to come to the South when he landed in Florida in 1513.

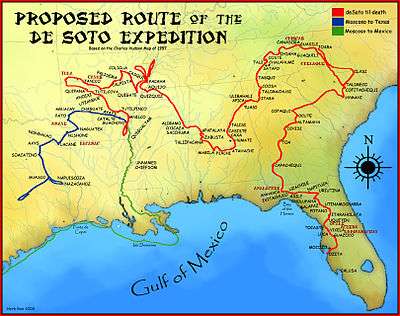

Hernando de Soto, a Spanish explorer and conquistador led the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day southern United States searching for gold, and a passage to China. De Sotos group were the first documented Europeans to cross the Mississippi River, on whose banks de Soto died in 1542. (Alonso Álvarez de Pineda was the first European to see the river, in 1519 when he sailed twenty miles up the river from the Gulf of Mexico).[2]

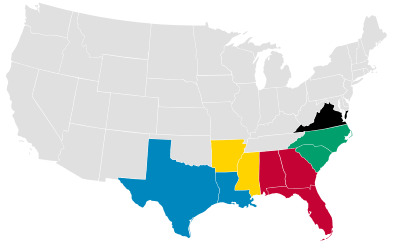

A vast undertaking, de Soto's North American expedition ranged across parts of the modern states of Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Texas.[1]

Among the first European settlements in North America were Spanish settlements in what would later become the state of Florida; the earliest was Tristán de Luna y Arellano's failed colony in what is now Pensacola in 1559. More successful was Pedro Menéndez de Avilés's St. Augustine, founded in 1565; St. Augustine remains the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the continental United States. Spain also colonized parts of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Spain issued land grants in the South from Kentucky to Florida and into the southwestern areas of what is now the United States. There was also a Spanish colony location near King Powhatan's ruling town in the Chesapeake Bay area of what is now Virginia and Maryland. It preceded Jamestown, the English colony, by as much as one hundred years.

French colonization

The first French settlement in what is now the Southern United States was Fort Caroline, located in what is now Jacksonville, Florida, in 1562. It was established as a haven for the Huguenots and was founded under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière and Jean Ribault. It was destroyed by the Spanish from the nearby colony of St. Augustine in 1565.

Later French arrived from the north. Having established agricultural colonies in Canada and built a fur trading network with Indians in the Great Lakes area, they began to explore the Mississippi River. The French called their territory Louisiana, in honor of their King Louis. France claimed Texas and set up several short-lived forts there, such as the one in Red River County, built in 1718. In 1817 the French pirate Jean Lafitte settled on Galveston Island; his colony there grew to more than 1,000 persons by 1818 but was abandoned in 1820. The most important French settlements were established at New Orleans and Mobile (originally called Bienville). Only a few settlers came from France directly, with others arriving from Haiti and Acadia.[3]

British colonial era (1607–1775)

Just before they defeated the Spanish Armada, the English began exploring the New World. In 1585 an expedition organized by Walter Raleigh established the first English settlement in the New World, on Roanoke Island, North Carolina. The colony failed to prosper, however, and the colonists were retrieved the following year by English supply ships. In 1587, Raleigh again sent out a group of colonists to Roanoke. From this colony, the first recorded European birth in North America, a child named Virginia Dare, was reported. That group of colonists disappeared and is known as the "Lost Colony". Many people theorize that they were either killed or taken in by local tribes.[4]

Like New England, the South was originally settled by English Protestants, later becoming a melting pot of religions as with other parts of the country. While the earlier attempt at colonization had failed on Roanoke Island, the English established their first permanent colony in America in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, at the mouth of the James River, which in turn empties into Chesapeake Bay.[5]

Settlement of Chesapeake Bay was driven by a desire to obtain precious metal resources, specifically gold. The colony was technically still within Spanish territorial claims, yet far enough from most Spanish settlements to avoid colonial clashes. As the "Anchor of the South", the region includes the Delmarva Peninsula and much of coastal Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

Early in the history of the colony, it became clear that the claims of gold deposits were vastly exaggerated. Referred to as the "Starving Time" of the Jamestown colony, the years from the time of landing in 1607 until 1609 were rife with famine and instability. However, Native American support, in addition to reinforcements from Britain, sustained the small colony. Due to continued political and economic instability, however, the charter of the Colony of Virginia was revoked in 1624. The primary cause of this revocation was the revelation that hundreds of settlers were dead or missing following an attack in 1622 by Native American tribes led by Opechancanough. A royal charter was established for Virginia, yet the House of Burgesses, formed in 1619, was allowed to continue as political leadership for the colony in conjunction with a royal governor.[6]

A key figure in the Virginia Colony and Southern political and cultural development generally was William Berkeley, who served, with some interruptions, as governor of Virginia from 1645 until 1675. His desire for an elite immigration to Virginia led to the "Second Sons" policy, in which younger sons of English aristocrats were recruited to emigrate to Virginia. Berkeley also emphasized the headright system, the offering of large tracts of land to those arriving in the colony. This early immigration by an elite contributed to the development of an aristocratic political and social structure in the South.[7]

English colonists, especially young indentured servants, continued to arrive along the southern Atlantic coast. Virginia became a prosperous English colony. The area now known as Georgia was also settled. Its beginnings under James Oglethorpe were as a resettlement colony for imprisoned debtors.[8]

Rise of tobacco culture and slavery in the colonial South

From the introduction of tobacco in 1613, its cultivation began to form the basis of the early Southern economy. Cotton did not become a mainstay until much later, after technological developments, especially the Whitney cotton gin of 1794, greatly increased the profitability of cotton cultivation. Until that point, most cotton was farmed in large plantations in the Province of Carolina, and tobacco, which could be grown profitably in farms of smaller scale, was the dominant cash crop export of the South and the Middle Atlantic States.

In 1640, the Virginia General Court recorded the earliest documentation of lifetime slavery when it sentenced John Punch to lifetime servitude under his master Hugh Gwyn for running away.[9][10]

The first slavery law in the British colonies was enacted by Massachusetts to enslave the indigenous population in 1641.[10]:62

During this period, life expectancy was often low, and indentured servants came from overpopulated European areas. With the lower price of servants compared to slaves, and the high mortality of the servants, planters often found it much more economical to use servants.

Because of this, slavery in the early colonial period differed greatly in the American colonies from that in the Caribbean. Often Caribbean slaves were worked literally to death on large sugar and rice plantations, while the American slave population had a higher life expectancy and was maintained through natural reproduction. This natural reproduction was important for the continuation of slavery after the prohibition on slave importation after about 1780.[11]

Much of the slave trade was conducted as part of the "triangular trade", a three-way exchange of slaves, rum, and sugar. Northern shippers purchased slaves using rum, made in New England from cane sugar, which was in turn grown in the Caribbean. This slave trade was generally able to fulfill labor needs in the South for the cultivation of tobacco after the decline of indentured servants. At approximately the point when tobacco labor needs began to increase, the mortality rate fell and all groups lived longer. By the late 17th century and early 18th century, slaves became economically viable sources of labor for the growing tobacco culture. Also, further south than the Mid-Atlantic, Southern settlers grew wealthy by raising and selling rice, indigo, and cotton. The plantations of South Carolina often were modeled on Caribbean plantations, albeit smaller in size.[12]

Growth of the Southern colonies

For details on each specific colony, see Province of Georgia, Province of Maryland, Province of North Carolina, Province of South Carolina, and Colony of Virginia.

By the end of the 17th century, the number of colonists was growing. The economies of the Southern colonies were tied to agriculture. During this time the great plantations were formed by wealthy colonists who saw great opportunity in the new country. Tobacco and cotton were the main cash crops of the areas and were readily accepted by English buyers. Rice and indigo were also grown in the area and exported to Europe. The plantation owners built a vast aristocratic life and accumulated a great deal of wealth from their land. They supported slavery as a means of working their land.

On the other side of the agricultural coin were the small yeoman farmers. They did not have the capability or wealth to operate large plantations. Instead, they worked small tracts of land and developed a political activism in response to the growing oligarchy of the plantation owners. Many politicians from this era were yeoman farmers speaking out to protect their rights as free men.

Charleston became a booming trade town for the southern colonies. The abundance of pine trees in the area provided raw materials for shipyards to develop, and the harbor provided a safe port for English ships bringing in imported goods. The colonists exported tobacco, cotton and textiles and imported tea, sugar, and slaves. The fact that these colonies maintained an independent trade relation with England and the rest of Europe became a major factor later on as tension mounted leading up to the American Revolutionary War.

After the late 17th century, the economies of the North and the South began to diverge, especially in coastal areas. The Southern emphasis on export production contrasted with the Northern emphasis on food production.

By the mid-18th century, the colonies of Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia had been established. In the upper colonies, that is, Maryland, Virginia, and portions of North Carolina, the tobacco culture prevailed. However, in the lower colonies of South Carolina and Georgia, cultivation focused more on cotton and rice.

American Revolution

The southern colonies, led by Virginia, gave strong support for the Patriot cause in solidarity with Massachusetts. Georgia, the newest, smallest, most exposed and militarily most vulnerable colony, hesitated briefly before joining the other 12 colonies in Congress. As soon as news arrived of the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Patriot forces took control of every colony, using secret committees that had been organized in the previous two years.[13] After the combat began, Governor Dunmore of Virginia was forced to flee to a British warship off the coast. In late 1775 he issued a proclamation offering freedom to slaves who escaped from Patriot owners and volunteer to fight for the British Army. Over 1,000 volunteered and served in British uniforms, chiefly in the Ethiopian Regiment. However, they were defeated in the Battle of Great Bridge, and most of them died of disease. The Royal Navy took Dunmore and other officials home in August 1776, and also carried to freedom 300 surviving former slaves.[14]

After their defeat at Saratoga in 1777 and the entry of the French into the American Revolutionary War, the British turned their attention to the South. With fewer regular troops at their disposal, the British commanders developed a "southern strategy" that relied heavily on volunteer soldiers and militia from the Loyalist element.[15]

Beginning in late December 1778, the British captured Savannah and controlled the Georgia coastline. In 1780 they seized Charleston, capturing a large American army. A significant victory at the Battle of Camden meant that royal forces soon controlled most of Georgia and South Carolina. The British set up a network of forts inland, expecting the Loyalists would rally to the flag. Far too few Loyalists turned out, however, and the British had to fight their way north into North Carolina and Virginia with a severely weakened army. Behind them most of the territory they had already captured dissolved into a chaotic guerrilla war, fought predominantly between bands of Loyalist and Patriot militia, with the Patriots retaking the areas the British had previously gained.[16]

The British army marched to Yorktown, Virginia, where they expected to be rescued by a British fleet. The fleet showed up but so did a larger French fleet, so the British fleet after the Battle of the Chesapeake returned to New York for reinforcements, leaving General Cornwallis trapped by the much larger American and French armies under Washington. He surrendered. The most prominent Loyalists, especially those who joined Loyalist regiments, were evacuated by the Royal Navy back to England, Canada, or other British colonies; they brought their slaves along, but lost their land. However, the great majority of Loyalists remained in the southern states and became American citizens.[17]

Antebellum era (1783–1861)

After the upheaval of the American Revolution effectively came to an end at the Siege of Yorktown (1781), the South became a major political force in the development of the United States. With the ratification of the Articles of Confederation, the South found political stability and a minimum of federal interference in state affairs. However, with this stability came a weakness in its design, and the inability of the Confederation to maintain economic viability eventually forced the creation of the United States Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787.

Importantly, Southerners of 1861 often believed their secessionist efforts and the Civil War paralleled the American Revolution, as a military and ideological "replay" of the latter.

Southern leaders were able to protect their sectional interests during the Constitutional Convention of 1787, preventing the insertion of any explicit anti-slavery position in the Constitution. Moreover, they were able to force the inclusion of the "fugitive slave clause" and the "Three-Fifths Compromise". Nevertheless, Congress retained the power to regulate the slave trade. Twenty years after the ratification of the Constitution, the law-making body prohibited the importation of slaves, effective January 1, 1808. While North and South were able to find common ground in order to gain the benefits of a strong Union, the unity achieved in the Constitution masked deeply rooted differences in economic and political interests. After the 1787 convention, two discrete understandings of American republicanism emerged.

For the North, a Puritanical republicanism predominated, with leaders such as Alexander Hamilton and John Adams.

In the South, agrarian laissez-faire formed the basis of political culture. Led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, this agrarian position is characterized by the epitaph on the grave of Jefferson. While including his "condition bettering" roles in the foundation of the University of Virginia, and the writing of the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, absent from the epitaph was his role as President of the United States. The development of Southern political thought thus focused on the ideal of the yeoman farmer; i.e., those who are tied to the land also have a vested interest in the stability and survival of the government.

Antebellum slavery

In the North, where slaves were mostly household servants or farm laborers, every state eventually abolished slavery; New Jersey was the last to pass a law on this subject (in 1804), although many of these laws were gradual in nature. Slavery was also abolished in the Northwest Territory and its states. Therefore, by 1804 the Mason–Dixon line (which separated free Pennsylvania and slave Maryland) became the dividing mark between "free" and "slave" states.

While about a third of white Southern families were slave owners, most were independent yeoman farmers. Nevertheless, the slave system represented the basis of the Southern social and economic system, and thus even non-slaveowners opposed any suggestions for terminating that system, whether through outright abolition or case-by-case manumission.

| Union | CSA | |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 22,000,000 (71%) | 9,000,000 (29%) |

| Free population | 22,000,000 | 5,500,000 |

| 1860 Border state slaves | 432,586 | NA |

| 1860 Southern slaves | NA | 3,500,000 |

| Soldiers | 2,200,000 (67%) | 1,064,000 (33%) |

| Railroad miles | 21,788 (71%) | 8,838 (29%) |

| Manufactured items | 90% | 10% |

| Firearm production | 97% | 3% |

| Bales of cotton in 1860 | Negligible | 4,500,000 |

| Bales of cotton in 1864 | Negligible | 300,000 |

| Pre-war U.S. exports | 30% | 70% |

The southern plantation economy was dependent on foreign trade, and the success of this trade helps explain why southern elites and some white yeomen were so violently opposed to abolition. There is considerable debate among scholars about whether or not the slaveholding South was a capitalist society and economy.[19]

Nullification crisis, political representation, and rising sectionalism

Although slavery had yet to become a major issue, states' rights would surface periodically in the early antebellum period, especially in the South. The election of Federalist member John Adams in the 1796 presidential election came in tandem with escalating tensions with France. In 1798, the XYZ Affair brought these tensions to the fore, and Adams became concerned about French power in America, fearing internal sabotage and malcontent that could be brought on by French agents. In response to these developments and to repeated attacks on Adams and the Federalists by Democratic-Republican publishers, Congress enacted the Alien and Sedition Acts. Enforcement of the acts resulted in the jailing of "seditious" Democratic-Republican editors throughout the North and South, and prompted the adoption of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798 (authored by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison), by the legislatures of those states.

Thirty years later, during the Nullification Crisis, the "Principles of '98" embodied in these resolutions were cited by leaders in South Carolina as a justification for state legislatures' asserting the power to nullify, or prevent the local application of, acts of the federal Congress that they deemed unconstitutional. The Nullification Crisis arose as a result of the Tariff of 1828, a set of high taxes on imports of manufactures, enacted by Congress as a protectionist measure to foster the development of domestic industry, primarily in the North. In 1832, the legislature of South Carolina nullified the entire "Tariff of Abominations", as the Tariff of 1828 was known in the South, prompting a stand-off between the state and federal government. On May 1, 1833, President Andrew Jackson wrote, "the tariff was only a pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object. The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question."[20] Although the crisis was resolved through a combination of the actions of the president, Congressional reduction of the tariff, and the Force Bill, it had lasting importance for the later development of secessionist thought.[21] An additional factor that led to Southern sectionalism was the proliferation of cultural and literary magazines such as the Southern Literary Messenger and DeBow's Review.[22]

Sectional parity and issue of slavery in new territories

Another issue feeding sectionalism was slavery, and especially the issue of whether to permit slavery in western territories seeking admission to the Union as states. In the early 19th century, as the cotton boom took hold, slavery became more economically viable on a large scale, and more Northerners began to perceive it as an economic threat, even if they remained indifferent to its moral dimension. While relatively few Northerners favored outright abolition, many more opposed the expansion of slavery to new territories, as in their view the availability of slaves lowered wages for free labor.

At the same time, Southerners increasingly perceived the economic and population growth of the North as threatening to their interests. For several decades after the Union was formed, as new states were admitted, North and South were able to finesse their sectional differences and maintain political balance by agreeing to admit "slave" and "free" states in equal numbers. By means of this compromise approach, the balance of power in the Senate could be extended indefinitely. The House of Representatives, however, was a different matter. As the North industrialized and its population grew, aided by a major influx of European immigrants, the Northern majority in the House of Representatives also grew, making Southern political leaders increasingly uncomfortable. Southerners became concerned that they would soon find themselves at the mercy of a federal government in which they no longer had sufficient representation to protect their interests. By the late 1840s, Senator Jefferson Davis from Mississippi stated that the new Northern majority in the Congress would make the government of the United States "an engine of Northern aggrandizement" and that Northern leaders had an agenda to "promote the industry of the United States at the expense of the people of the South."

With the Mexican War, which alarmed many Northerners by adding new territory on the Southern side of the free-slave boundary, the slavery-in-the-territories issue heated up dramatically. After a four-year sectional conflict, the Compromise of 1850 narrowly averted civil war with a complex deal in which California was admitted as a free state, including Southern California, thus preventing a separate slave territory there, while slavery was allowed in the New Mexico and Utah territories and a stronger Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, requiring all citizens to assist in recapturing runaway slaves wherever found. Four years later, the peace bought with successive compromises finally came to an end. In the Kansas–Nebraska Act, Congress left the issue of slavery to a vote in each territory, thereby provoking a breakdown of law and order as rival groups of pro- and anti-slavery immigrants competed to populate the newly settled region.

Election of 1860, secession, and Lincoln's response

For many Southerners, the last straws were the raid on Harper's Ferry in 1859 by fanatical abolitionist John Brown, immediately followed by a Northern Republican presidential victory in the election of 1860. Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected president with only 40% of the popular vote and with hardly any popular support in the South.[23]

Members of the South Carolina legislature had previously sworn to secede from the Union if Lincoln was elected, and the state declared its secession on December 20, 1860. In January and February, six other cotton states of the Deep South followed suit: Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. The other eight slave states postponed a decision, but the seven formed a new government in Montgomery, Alabama, in February: the Confederate States of America. Throughout the South, Confederates seized federal arsenals and forts, without resistance, and forced the surrender of all U.S. forces in Texas. The sitting President, James Buchanan, believed he had no constitutional power to act, and in the four months between Lincoln's election and his inauguration, the South strengthened its military position.[24]

In Washington, proposals for compromise and reunion went nowhere, as the Confederates demanded complete, total, permanent independence. When Lincoln dispatched a supply ship to federal-held Fort Sumter, in South Carolina, the Confederate government ordered an attack on the fort, which surrendered on April 13. President Lincoln called upon the states to supply 75,000 troops to serve for ninety days to recover federal property, and, forced to choose sides, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina promptly voted to secede. Kentucky declared its neutrality.[25]

Civil War (1861–1865)

The seceded states, joined together as the Confederate States of America and only wanting to be independent, had no desire to conquer any state north of its border. After secession, no compromise was possible, because the Confederacy insisted on its independence and the Lincoln Administration refused to meet with President Davis's commissioners. Instead of diplomacy, Lincoln ordered that a Navy fleet of warships and troop transports be sent to Charleston Harbor to reinforce and resupply Fort Sumter. Just before the fleet was about to enter the harbor, Confederates forced the Federal garrison holed up in the fort to surrender. That incident, although only a cannon duel that produced no deaths, allowed President Lincoln to proclaim that United States forces had been attacked and justified his calling up of troops to invade the seceded states. In response the Confederate military strategy was to hold its territory together, gain worldwide recognition, and inflict so much punishment on invaders that the Northerners would tire of an expensive war and negotiate a peace treaty that would recognize the independence of the CSA. Two Confederate counter-offensives into Maryland and southern Pennsylvania failed to influence Federal elections as hoped. The victory of Lincoln and his party in the 1864 elections made the Union's military victory only a matter of time.

Both sides wanted the border states, but the Union military forces took control of all of them in 1861–1862. Union victories in western Virginia allowed a Unionist government based in Wheeling to take control of western Virginia and, with Washington's approval, create the new state of West Virginia.[26] The Confederacy did recruit troops in the border states, but the enormous advantage of controlling them went to the Union.

The Union naval blockade, starting in May 1861, reduced exports by 95%; only small, fast blockade runners—mostly owned and operated by British interests—could get through. The South's vast cotton crops became nearly worthless.[27]

In 1861 the rebels assumed that "King Cotton" was so powerful that the threat of losing their supplies would induce Britain and France to enter the war as allies, and thereby frustrate Union efforts. Confederate leaders were ignorant of European conditions; Britain depended on the Union for its food supply, and would not benefit from an extremely expensive major war with the U.S. The Confederacy moved its capital from a defensible location in remote Montgomery, Alabama, to the more cosmopolitan city of Richmond, Virginia, only 100 miles (160 km) from Washington. Richmond had the heritage and facilities to match those of Washington, but its proximity to the Union forced the CSA to spend most of its war-making capability to defend Richmond.

Leadership

The strength of the Confederacy included an unusually strong officer corps—about a third of the officers of the U.S. Army had resigned and joined. But the political leadership was not very effective. A classic interpretation is that the Confederacy "died of states' rights", as governors of Texas, Georgia, and North Carolina refused Richmond's request for troops.[28]

The Confederacy decided not to have political parties. There was a strong sense that parties were divisive and would weaken the war effort. Historians, however, agree that the lack of parties weakened the political system. Instead of having a viable alternative to the current system, as expressed by a rival party, the people could only grumble and complain and lose faith.[29]:690

Historians disparage the effectiveness of President Jefferson Davis, with a consensus holding that he was much less effective than Abraham Lincoln.[29]:754 As a former Army officer, senator, and Secretary of War, he possessed the stature and experience to be president, but certain character defects undercut his performance. He played favorites and was imperious, frosty, and quarrelsome. By dispensing with parties, he lost the chance to build a grass roots network that would provide critically needed support in dark hours. Instead, he took the brunt of the blame for all difficulties and disasters. Davis was animated by a profound vision of a powerful, opulent new nation, the Confederate States of America, premised on the right of its white citizens to self-government. However, in dramatic contrast to Lincoln, he was never able to articulate that vision or provide a coherent strategy to fight the war. He neglected the civilian needs of the Confederacy while spending too much time meddling in military details. Davis's meddling in military strategy proved counterproductive. His explicit orders that Vicksburg be held no matter what sabotaged the only feasible defense and led directly to the fall of the city in 1863.[30][31]

Abolition of slavery

By 1862 most northern leaders realized that the mainstay of Southern secession, slavery, had to be attacked head-on. All the border states rejected President Lincoln's proposal for compensated emancipation. However, by 1865 all had begun the abolition of slavery, except Kentucky and Delaware. The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order issued by Lincoln on January 1, 1863. In a single stroke it changed the legal status, as recognized by the U.S. government, of 3 million slaves in designated areas of the Confederacy from "slave" to "free". It had the practical effect that as soon as a slave escaped the control of the Confederate government, by running away or through advances of federal troops, the slave became legally and actually free. Plantation owners, realizing that emancipation would destroy their economic system, sometimes moved their slaves as far as possible out of reach of the Union Army. By June 1865, the Union Army controlled all of the Confederacy and liberated all of the designated slaves. The owners were never compensated. Nor were the slaves themselves.[32] Many of the freedmen remained on the same plantation, others crowded into refugee camps operated by the Freedmen's Bureau. The Bureau provided food, housing, clothing, medical care, church services, some schooling, legal support, and arranged for labor contracts.[33]

The severe dislocations of war and Reconstruction affected the black population, with a large amount of sickness and death.[34]

Railroads

The Union had a 3-1 superiority in railroad mileage and (even more important) an overwhelming advantage in engineers and mechanics in the rolling mills, machine shops, factories, roundhouses and repair yards that produced and maintained rails, bridging equipage, locomotives, rolling stock, signaling gear, and telegraph equipment. In peacetime the South imported all its railroad gear from the North; the Union blockade completely cut off such imports. The lines in the South were mostly designed for short hauls, as from cotton areas to river or ocean ports; they were not designed for trips of more than 100 miles or so, and such trips involved numerous changes of trains and layovers.[35] The South's 8,500 miles (13,700 km) of track comprised enough of a railroad system to handle essential military traffic along some internal lines, assuming it could be defended and maintained. As the system deteriorated because of worn out equipment, accidents and sabotage, the South was unable to construct or even repair new locomotives, cars, signals or track. Little new equipment ever arrived, although rails in remote areas such as Florida were removed and put to more efficient use in the war zones. Realizing their enemy's dilemma, Union cavalry raids routinely destroyed locomotives, cars, rails, roundhouses, trestles, bridges, and telegraph wires. By the end of the war, the southern railroad system was totally ruined. Meanwhile, the Union army rebuilt rail lines to supply its forces. A Union railroad through hostile territory, as from Nashville to Atlanta in 1864, was an essential but fragile lifeline—it took a whole army to guard it, because each foot of track had to be secure. Large numbers of Union soldiers throughout the war were assigned to guard duty and, while always ready for action, seldom saw any fighting.[36]

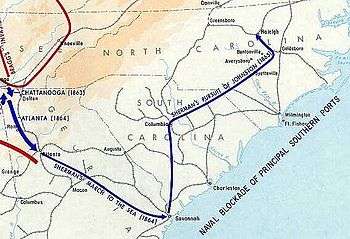

Sherman's March

By 1864 the top Union generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman realized the weakest point of the Confederate armies was the decrepitude of the southern infrastructure, so they escalated efforts to wear it down. Cavalry raids were the favorite device, with instructions to ruin railroads and bridges. Sherman's insight was deeper. He focused on the trust the rebels had in their Confederacy as a living nation, and he set out to destroy that trust; he predicted his raid would "demonstrate the vulnerability of the South, and make its inhabitants feel that war and individual ruin are synonymous terms."[37] Sherman's "March to the Sea" from Atlanta to Savannah in the fall of 1864 burned and ruined every part of the industrial, commercial, transportation and agricultural infrastructure it touched, but the actual damage was confined to a swath of territory totaling about 15% of Georgia. Sherman struck at Georgia in October, just after the harvest, when the food supplies for the next year had been gathered and were exposed to destruction. In early 1865 Sherman's army moved north through the Carolinas in a campaign even more devastating than the march through Georgia. More telling than the twisted rails, smoldering main streets, dead cattle, burning barns and ransacked houses was the bitter realization among civilians and soldiers throughout the remaining Confederacy that if they persisted, sooner or later their homes and communities would receive the same treatment.[38]

Out-gunned, out-manned, and out-financed, defeat loomed after four years of fighting. When Lee surrendered to Grant in April 1865, the Confederacy fell. There was no insurgency, no treason trials, and only one war crimes trial.

Reconstruction (1863–1877)

Reconstruction began as soon as the Union Army took control of a state; the start and ending times varied by state, beginning in 1863 and ending in 1877. Slavery ended and the large slave-based plantations were mostly subdivided into tenant or sharecropper farms of 20–40 acres (8.1–16.2 ha). Many white farmers (and some blacks) owned their land. However sharecropping, along with tenant farming, became a dominant form in the cotton South from the 1870s to the 1950s, among both blacks and whites. By the 1960s both had largely disappeared. Sharecropping was a way for very poor farmers to earn a living from land owned by someone else. The landowner provided land, housing, tools and seed, and perhaps a mule, and a local merchant provided food and supplies on credit. At harvest time the sharecropper received a share of the crop (from one-third to one-half, with the landowner taking the rest). The cropper used his share to pay off his debt to the merchant. The system started with blacks when large plantations were subdivided. By the 1880s white farmers also became sharecroppers. The system was distinct from that of the tenant farmer, who rented the land, provided his own tools and mule, and received half the crop. Landowners provided more supervision to sharecroppers, and less or none to tenant farmers.[39][40]

Material ruin and human losses

Reconstruction played out against a backdrop of a once prosperous economy that lay in ruins. According to Hesseltine (1936),

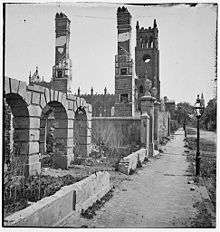

Throughout the South, fences were down, weeds had overrun the fields, windows were broken, live stock had disappeared. The assessed valuation of property declined from 30 to 60 percent in the decade after 1860. In Mobile, business was stagnant; Chattanooga and Nashville were ruined; and Atlanta's industrial sections were in ashes.[41]

In Charleston, a journalist in September 1865 discovered "a city of ruins, of desolation, of vacant houses, of widowed women, of rotten wharves, of deserted warehouses, of weed-wild gardens, of miles of grass-grown streets, of acres of pitiful and voiceful barrenness."[42][43]

Reports from Confederate officials show 94,000 killed in battle and another 164,000 who died of disease, with about 194,000 wounded.[44] The Confederate official counts are too low; perhaps another 75,000-100,000 Confederate soldiers died because of the war.[45]

The number of civilian deaths is unknown, but was highest among refugees and former slaves.[34][46] Most of the war was fought in Virginia and Tennessee, but every Confederate state was affected, as well as Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Indian Territory; Pennsylvania was the only northerner state to be the scene of major action, during the Gettysburg Campaign. In the Confederacy there was little military action in Texas and Florida. Of 645 counties in 9 Confederate states (excluding Texas and Florida), there was Union military action in 56% of them, containing 63% of the whites and 64% of the slaves in 1860; however, by the time the action took place some people had fled to safer areas, so the exact population exposed to war is unknown.[47]

The Confederacy in 1861 had 297 towns and cities with 835,000 people; of these 162 with 681,000 people were at one point occupied by Union forces. Ten were destroyed or severely damaged by war action, including Atlanta (with an 1860 population of 9,600), Columbia, and Richmond (with prewar populations of 8,100 and 37,900, respectively), plus Charleston, much of which was destroyed in an accidental fire in 1861. These eleven contained 115,900 people in the 1860 census, or 14% of the urban South. Historians have not estimated their population when they were invaded. The number of people who lived in the destroyed towns represented just over 1% of the Confederacy's population. In addition, 45 courthouses were burned (out of 830). The South's agriculture was not highly mechanized. The value of farm implements and machinery in the 1860 Census was $81 million; by 1870, there was 40% less, or $48 million worth. Many old tools had broken through heavy use and could not be replaced; even repairs were difficult.[47]

The economic calamity suffered by the South during the war affected every family. Except for land, most assets and investments had vanished with slavery, but debts were left behind. Worst of all were the human deaths and amputations. Most farms were intact but most had lost their horses, mules and cattle; fences and barns were in disrepair. Prices for cotton had plunged. The rebuilding would take years and require outside investment because the devastation was so thorough. One historian has summarized the collapse of the transportation infrastructure needed for economic recovery:[48]

One of the greatest calamities which confronted Southerners was the havoc wrought on the transportation system. Roads were impassable or nonexistent, and bridges were destroyed or washed away. The important river traffic was at a standstill: levees were broken, channels were blocked, the few steamboats which had not been captured or destroyed were in a state of disrepair, wharves had decayed or were missing, and trained personnel were dead or dispersed. Horses, mules, oxen, carriages, wagons, and carts had nearly all fallen prey at one time or another to the contending armies. The railroads were paralyzed, with most of the companies bankrupt. These lines had been the special target of the enemy. On one stretch of 114 miles in Alabama, every bridge and trestle was destroyed, cross-ties rotten, buildings burned, water-tanks gone, ditches filled up, and tracks grown up in weeds and bushes. ... Communication centers like Columbia and Atlanta were in ruins; shops and foundries were wrecked or in disrepair. Even those areas bypassed by battle had been pirated for equipment needed on the battlefront, and the wear and tear of wartime usage without adequate repairs or replacements reduced all to a state of disintegration.

Railroad mileage was of course located mostly in rural areas. The war followed the rails, and over two-thirds of the South's rails, bridges, rail yards, repair shops and rolling stock were in areas reached by Union armies, which systematically destroyed what it could. The South had 9,400 miles (15,100 km) of track, and 6,500 miles (10,500 km) were in areas reached by the Union armies. About 4,400 miles (7,100 km) were in areas where Sherman and other Union generals adopted a policy of systematic destruction of the rail system. Even in untouched areas, the lack of maintenance and repair, the absence of new equipment, the heavy over-use, and the deliberate movement of equipment by the Confederates from remote areas to the war zone guaranteed the system would be virtually ruined at war's end.[47]

Political Reconstruction (1863–1877)

Reconstruction was the process by which the states returned to full status. It took place in four stages, which varied by state. Tennessee and the border states were not affected. First came the governments appointed by President Andrew Johnson that lasted 1865–66. The Freedmen's Bureau was active, helping refugees, setting up employment contracts for Freedmen, and setting up courts and schools for the freedmen. Second came rule by the U.S. Army, which held elections that included all freedmen but excluded over 10,000 Confederate leaders. Third was "Radical Reconstruction" or "Black Reconstruction" in which a Republican coalition governed the state, comprising a coalition of freedmen, scalawags (native whites) and carpetbaggers (migrants from the North). Violent resistance by the Ku Klux Klan and related groups was suppressed by President Ulysses S. Grant and the vigorous use of federal courts and soldiers in 1868–70. The Reconstruction governments spent large sums on railroad subsidies and schools, but quadrupled taxes and set off a tax revolt among conservatives. Stage four was reached by 1876 as the white conservative coalition, called Redeemers, had won political control of all the states except South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana. The disputed presidential election of 1876 hinged on those three violently contested states. The outcome was the Compromise of 1877, whereby the Republican Rutherford Hayes became president and all federal troops were withdrawn from the South, leading to the immediate collapse of the last Republican state governments.

Railroads

The building of a new, modern rail system was widely seen as essential to the economic recovery of the South, and modernizers invested in a "Gospel of Prosperity". Northern money financed the rebuilding and dramatic expansion of railroads throughout the South; they were modernized in terms of rail gauge, equipment and standards of service. the Southern network expanded from 11,000 miles (18,000 km) in 1870 to 29,000 miles (47,000 km) in 1890. Railroads helped create a mechanically skilled group of craftsmen and broke the isolation of much of the region. Passengers were few, however, and apart from hauling the cotton crop when it was harvested, there was little freight traffic.[49][50] The lines were owned and directed overwhelmingly by Northerners, who often had to pay heavy bribes to corrupt politicians for needed legislation.[51]

The Panic of 1873 ended the expansion everywhere in the United States, leaving many Southern lines bankrupt or barely able to pay the interest on their bonds.

Backlash to Reconstruction

Reconstruction was a harsh time for many white Southerners who found themselves without many of the basic rights of citizenship (such as the ability to vote). Reconstruction was also a time when many African Americans began to secure these same rights. With the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution (which outlawed slavery), the 14th Amendment (which granted full U.S. citizenship to African Americans) and the 15th Amendment (which extended the right to vote to black males), African Americans in the South began to enjoy more rights than they had ever had in the past.

A reaction to the defeat and changes in society began immediately, with vigilante groups such as the Ku Klux Klan arising in 1866 as the first line of insurgents. They attacked and killed both freedmen and their white allies. By the 1870s, more organized paramilitary groups, such as the White League and Red Shirts, took part in turning Republicans out of office and barring or intimidating blacks from voting.

Origins of the New South (1877–1913)

The classic history was written by C. Vann Woodward, The Origins of the New South: 1877–1913, which was published in 1951 by Louisiana State University Press. Sheldon Hackney explains:

Of one thing we may be certain at the outset. The durability of Origins of the New South is not a result of its ennobling and uplifting message. It is the story of the decay and decline of the aristocracy, the suffering and betrayal of the poor whites, and the rise and transformation of a middle class. It is not a happy story. The Redeemers are revealed to be as venal as the carpetbaggers. The declining aristocracy are ineffectual and money hungry, and in the last analysis they subordinated the values of their political and social heritage in order to maintain control over the black population. The poor whites suffered from strange malignancies of racism and conspiracy-mindedness, and the rising middle class was timid and self-interested even in its reform movement. The most sympathetic characters in the whole sordid affair are simply those who are too powerless to be blamed for their actions.[52]

Race: from Jim Crow to the Civil Rights Movement

After the Redeemers took control in the mid-1870s, Jim Crow laws were created to legally enforce racial segregation in public facilities and services. The phrase "separate but equal", upheld in the 1896 Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, came to represent the notion that whites and blacks should have access to physically separate but ostensibly equal facilities. It would not be until 1954 that Plessy was overturned in Brown v. Board of Education, and only in the late 1960s was segregation fully repealed by legislation passed following the Civil Rights Movement.

The most extreme white leader was Senator Ben Tillman of South Carolina, who proudly proclaimed in 1900, "We have done our level best [to prevent blacks from voting] ... we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them. We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it."[53] With no voting rights and no voice in government, blacks in the South were subjected to a system of segregation and discrimination. Blacks and whites attended separate schools. Blacks could not serve on juries, which meant that they had little if any legal recourse. In Black Boy, an autobiographical account of life during this time, Richard Wright writes about being struck with a bottle and knocked from a moving truck for failing to call a white man "sir".[54] Between 1889 and 1922, the NAACP calculates that lynchings reached their worst level in history, with almost 3,500 people, three-fourths of them black men, murdered.[55]

African-Americans responded with two major reactions: the Great Migration and the Civil Rights Movement.

The Great Migration began during World War I, hitting its high point during World War II. During this migration, black people left the racism and lack of opportunities in the South and settled in northern cities like Chicago, where they found work in factories and other sectors of the economy.[56] This migration produced a new sense of independence in the black community and contributed to the vibrant black urban culture seen in the emergence of jazz and the blues from New Orleans and its spread north to Memphis and Chicago.[57]

The migration also empowered the growing Civil Rights Movement.[58] While the Civil Rights Movement existed in all parts of the United States, its focus was against the Jim Crow laws in the South. Most of the major events in the movement occurred in the South, including the Montgomery bus boycott, the Mississippi Freedom Summer, the march on Selma, Alabama, and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. In addition, some of the most important writings to come out of the movement were written in the South, such as King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail".

As a result of the Civil Rights Laws of 1964 and 1965, all Jim Crow laws across the South were dropped. This change in the South's racial climate combined with the new industrialization in the region to help usher in what is called the New South.

Rural South

Agriculture's share of the labor force by region, 1890:

| Northeast | 15% |

| Middle Atlantic | 17% |

| Midwest | 43% |

| South Atlantic | 63% |

| South Central | 67% |

| West | 29% |

| Source[60] | |

The South remained heavily rural until World War II. There were only a few scattered cities; small courthouse towns served the farm population. Local politics revolved around the politicians and lawyers based at the courthouse. Mill towns, narrowly focused on textile production or cigarette manufacture, began opening in the Piedmont region, especially in the Carolinas. Racial segregation and outward signs of inequality were everywhere, and rarely were challenged. Blacks who violated the color line were liable to expulsion or lynching.[61] Cotton became even more important than before, even though prices were much lower. White southerners showed a reluctance to move north, or to move to cities, so the number of small farms proliferated, and they became smaller and smaller as the population grew.

Many of the white farmers, and some of the blacks, were tenant farmers who owned their work animals and tools, and rented their land. Others were day laborers or impoverished sharecroppers, who worked under the supervision of the landowner. Sharecropping was a way for landless farmers (both black and white) to earn a living. The landowner provided land, housing, tools and seed, and perhaps a mule, and a local merchant loaned money for food and supplies. At harvest time the sharecropper received a share of the crop (from one-third to one-half), which paid off his debt to the merchant. By the late 1860s white farmers also became sharecroppers. The cropper system was a step below that of the tenant farmer, who rented the land, provided his own tools and mule, and received half the crop. Landowners provided more supervision to sharecroppers, and less or none to tenant farmers.[62]

There was little cash in circulation, since most farmers operated on credit accounts from local merchants, and paid off their debts at cotton harvest time in the fall. Although there were small country churches everywhere, there were only a few dilapidated schools; high schools were available in the cities, which were few in number, but were hard to find in most rural areas. All the Southern high schools combined graduated 66,000 students in 1928. The school terms were shorter in the South, and total spending per student was much lower. Nationwide, the students in elementary and secondary schools attended 140 days of school in 1928, compared to 123 days for white children in the South and 95 for blacks. The national average in 1928 for school expenditures was $70,700 for every 1,000 children aged 5–17. Only Florida reached that level; seven of the eleven Southern states spent under $31,000 per 1000 children.[63][64] Conditions were marginally better in newer areas, especially in Texas and central Florida, with the deepest poverty in South Carolina, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas. Hookworm[65] and other diseases sapped the vitality of a large fraction of Southerners.[66][67]

Collapse of the Black belt socio-economic plantation system

Economic historians of the South generally emphasize the continuity of the system of white supremacy and cotton plantations in the Black Belt from the late colonial era into the mid-20th century, when it collapsed. Harold D, Woodman summarizes the explanation that external forces caused the disintegration from the 1920s to the 1970s:

- When a significant change finally occurred, its impetus came from outside the South. Depression-bred New Deal reforms, war-induced demand for labor in the North, perfection of cotton-picking machinery, and civil rights legislation and court decisions finally... destroyed the plantation system, undermined landlord or merchant hegemony, diversified agriculture and transformed it from a labor- to a capital-intensive industry, and ended the legal and extra-legal support for racism. The discontinuity that war, invasion, military occupation, the confiscation of slave property, and state and national legislation failed to bring in the mid-19th century, finally arrived in the second third of the 20th century. A "second reconstruction" created a real New South.[68]

Creating the "New South" (1945–present)

In the decades after World War II, the old agrarian Southern economy evolved into the "New South" – a manufacturing region with strong roots in laissez-faire capitalism. As a result, high-rise buildings began to crowd the skylines of Atlanta, Birmingham, Charlotte, Raleigh-Durham, Houston, Dallas, Nashville, and Little Rock.[69] King Cotton was dethroned. There were 1.5 million cotton farms in 1945, and only 18,600 remained in 2009. The Census stopped counting sharecroppers because they were so few.[39]

The industrialization and modernization of the South picked up speed with the ending of racial segregation in the 1960s. Today, the economy of the South is a diverse mixture of agriculture, light and heavy industry, tourism, and high technology companies, and is becoming increasingly integrated into the global economy.[70] State governments aggressively recruited northern business to the "Sun Belt", promising more enjoyable weather and recreation, a lower cost of living, an increasingly skilled work force, minimal taxes, weak labor unions, and a business-friendly attitude.[71] With the expansion of jobs in the South, there has been migration of northerners, increasing the population and political influence of southern states. The newcomers displaced the old rural political system built around courthouse cliques. The suburbs became the base of the emerging Republican Party, which became dominant in presidential elections by 1968, and in state politics by the 1990s.[72]

The South urbanized as the cotton base collapsed, especially east of the Mississippi River. Farming was much less important (and the remaining farmers more often specialized in soybeans and cattle, or citrus in Florida). The need for cotton pickers ended with the utilization of picking machines after 1945, and nearly all of the black cotton farmers moved to urban areas, often in the North. Whites, who had been farmers, usually moved to nearby towns. Factories and service industries were opened in those towns for employment.[73]

Millions of Northern retirees moved down for the mild winters. These well-to-do retirees often moved into expensive homes located near the ocean, which, over the years, resulted in increasingly expensive hurricane damages. Tourism became a major industry, especially in venues such as Williamsburg, Virginia, Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, San Antonio, Texas, Orlando, Florida, and Branson, Missouri.[74]

Sociologists report that Southern collective identity stems from political, demographic and cultural distinctiveness. Studies have shown that Southerners are more conservative than non-Southerners in several areas including religion, morality, international relations and race relations.[75][76] In the 21st century, the South remains demographically distinct with higher percentages of blacks, lower percentages of high school graduates, lower housing values, lower household incomes and higher percentages of people in poverty.[77] That, combined with the fact that Southerners continue to maintain strong loyalty to family ties, has led some sociologists to label white Southerners a "quasi-ethnic regional group".[78]

Apart from the still-distinctive climate, the living experience in the South increasingly resembles the rest of the nation. The arrival of millions of Northerners (especially in the suburbs and coastal areas)[79] and millions of Hispanics[80] means the introduction of cultural values and social norms not rooted in Southern traditions.[81][82] Observers conclude that collective identity and Southern distinctiveness are thus declining, particularly when defined against "an earlier South that was somehow more authentic, real, more unified and distinct."[83] The process has worked both ways, however, with aspects of Southern culture spreading throughout a greater portion of the rest of the United States in a process termed "Southernization".[84]

Southern presidents

The South has long been a center of political power in the United States, especially in regard to presidential elections. During the history of the United States, the South has supplied many of the 45 presidents. Virginia specifically was the birthplace of seven of the nation's first twelve presidents (including four of the first five).

Presidents born in the South and identified with the region include:

- George Washington of Virginia (term 1789–1797)

- Thomas Jefferson of Virginia (term 1801–1809)

- James Madison of Virginia (term 1809–1817)

- James Monroe of Virginia (term 1817–1825)

- Andrew Jackson, born in either North Carolina or South Carolina, identified with Tennessee (term 1829–1837)

- John Tyler of Virginia (term 1841–1845)

- James Knox Polk, born in North Carolina, identified with Tennessee (term 1845–1849)

- Polk was born in North Carolina, but spent his adult and political life in Tennessee.

- Zachary Taylor of Virginia (term 1849–1850)

- Andrew Johnson, born in North Carolina, identified with Tennessee (term 1865–1869)

- Johnson was born in North Carolina, but spent his adult and political life in Tennessee.

- Lyndon Baines Johnson of Texas (term 1963–1969)

- Jimmy Carter of Georgia (term 1977–1981)

- Bill Clinton of Arkansas (term 1993–2001)

One president was born in the South, and is identified both with the South and elsewhere:

- Woodrow Wilson was born and raised in the South. His academic and political career was in the North but he retained strong ties with the South.

Presidents born outside the South, but generally identified with the region:

- George H. W. Bush (term 1989–1993) was born in Massachusetts, but spent his adult life in Texas.

- George W. Bush, born in Connecticut, lived from early childhood in Texas.

Presidents born in Southern states, but not primarily identified with that region, include:

- William Henry Harrison, born in Virginia, identified with Midwest

- Abraham Lincoln, born in Kentucky, left at age 7; identified with Illinois

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, born in Texas, left at age 2 and identified with Kansas

This list encompasses members of the Whig Party, Republican Party and the Democratic Party; in addition, Washington, while officially non-partisan, was generally associated with the Federalist Party.

They have also supplied Presidential losers:

- Charles Pinckney of South Carolina – 1804 election, 1808 election

- Henry Clay of Kentucky (born in Virginia) – 1824 election, 1832 election, 1844 election

- William Crawford of Georgia (born in Virginia) – 1824 election

- Hugh White of Tennessee (born in North Carolina) – 1836 election

- John Breckinridge of Kentucky – 1860 election

- John Bell of Tennessee – 1860 election

- John W. Davis of West Virginia – 1924 election

- J. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina – 1948 election

- George Wallace of Alabama – 1968 election; last third-party candidate to win any state's popular vote

- Al Gore of Tennessee (born in Washington, D.C.) – 2000 election

See also

- African-American culture

- African-American history

- American gentry

- Black Belt in the American South

- Border states (American Civil War)

- Civil rights movement (1896–1954)

- Civil rights movement in popular culture

- Colonial history of the United States

- Culture of honor (Southern United States)

- Culture of the Southern United States

- Dueling in the Southern United States

- Juneteenth

- Politics of the Southern United States

- Southern United States literature

Footnotes

- Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press.

- Morison, Samuel (1974). The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages, 1492–1616. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Weddle, Robert S. (1991). The French Thorn: Rival Explorers in the Spanish Sea, 1682–1762. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-480-7.

- Kupperman, Karen Ordahl (2007). Roanoke: The Abandoned Colony. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742552630.

- Robert Appelbaum, and John Wood Sweet, eds., Envisioning an English Empire: Jamestown and the Making of the North Atlantic World (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012)

- Billings, Warren M.; Selby, John E.; Tate, Thad W. (1986). Colonial Virginia: A History. KTO Press. ISBN 9780527187224.

- Warren M. Billings, Sir William Berkeley and the Forging of Colonial Virginia (LSU Press, 2004)

- Coleman, Kenneth (1976). Colonial Georgia: A History. Scribner's Sons. ISBN 9780684145556.

- Jordan, Winthrop (1968). White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807871419.

- Higginbotham, A. Leon (1975). In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780195027457.

- C. Vann Woodward, American Counterpoint: Slavery and Racism in the North-South Dialogue (1971) pp. 78-91

- Walter B. Edgar (1998). South Carolina: A History. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 131–54. ISBN 9781570032554.

- Alden, John Richard (1957). The South in the Revolution, 1763–1789. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807100035.

- W. Hugh Moomaw, "The British Leave Colonial Virginia", Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (1958) 66#2 pp. 147-160 in JSTOR

- Jeffrey J. Crow and Larry E. Tise, eds., The Southern Experience in the American Revolution (1978) p. 157–9

- Henry Lumpkin, From Savannah to Yorktown: The American Revolution in the South (2000)

- Morrissey, Brendan (1997). Yorktown 1781: The World Turned Upside Down. Praeger. ISBN 9780275984571.

- Railroad mileage is from: Chauncey Depew (ed.), One Hundred Years of American Commerce 1795–1895, p. 111; For other data see: 1860 US census and Carter, Susan B., ed. The Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition (5 vols), 2006.

- "Capitalism and Slavery in the United States (Topical Guide) | H-Slavery | H-Net". networks.h-net.org. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- Jon Meacham (2009), American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House, New York: Random House, p. 247; Correspondence of Andrew Jackson, Vol. V, p. 72.

- Freehling, William W. (1992) [1966]. Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina, 1816–1836. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507681-8.

- Haveman, H. A. (2004). "Antebellum literary culture and the evolution of American magazines". Poetics. 32 (1): 5–28. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2003.12.002.

- Potter, David (1977). The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780061319297.

- Robert J. Cook and William L. Barney, Secession Winter: When the Union Fell Apart (2013)

- William C. Davis, Look Away! A History of the Confederate States of America (2003).

- Rice, Otis K.; Brown, Stephen W. (1994). West Virginia: A History (2nd ed.). Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 111–123. ISBN 0-8131-1854-9.

- Surdam, David G. (2001). Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War. Columbia: U. of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-407-9.

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence (1925). "Local Defense and the Overthrow of the Confederacy: A Study in State Rights". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 11 (4): 490–525. doi:10.2307/1895910. JSTOR 1895910.

- James M. McPherson (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743902.

- Cooper, William James (2000). Jefferson Davis, American: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-56916-4; compare Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2005). Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-82490-6.

- For a defense of Davis see Johnson, Ludwell H. (1981). "Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln As War Presidents: Nothing Succeeds Like Success". Civil War History. 27 (1): 49–63. doi:10.1353/cwh.1981.0055.

- Michael Vorenberg, ed. The Emancipation Proclamation: A Brief History with Documents (2010),

- Paul A. Cimbala, The Freedmen's Bureau: Reconstructing the American South after the Civil War (2005)

- Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction (2015)

- Marrs, Aaron W. (2009). Railroads in the Old South: Pursuing Progress in a Slave Society. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9130-4.

- Turner, George Edgar (1953). Victory Rode the Rails: The Strategic Place of the Railroads in the Civil War. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Beringer, Richard E.; et al. (1991). Why the South Lost the Civil War. University of Georgia Press. p. 349. ISBN 0-8203-1396-3.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre (2008). Southern Storm: Sherman's March to the Sea. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-059867-9.

- Brown, D. Clayton (2010). King Cotton in Modern America: A Cultural, Political, and Economic History since 1945. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-798-1.

- Joseph D. Reid, "Sharecropping as an understandable market response: The post-bellum South." Journal of Economic History (1973) 33#1 pp: 106-130. in JSTOR

- Hesseltine, William B. (1936). A History of the South, 1607–1936. New York: Prentice-Hall. pp. 573–574.

- Rosen, Robert N. (1997). A Short History of Charleston. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 121. ISBN 1-57003-197-5.

- For more detail see Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson (1917). A History of the United States Since the Civil War. 1. pp. 56–67.

- For details see Livermore, Thomas L. (1901). Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America 1861–65. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin.

- Hacker, J. David (2011). "A Census-Based Count of the Civil War Dead". Civil War History. 57 (4): 307–348. doi:10.1353/cwh.2011.0061. PMID 22512048.

- Humphreys, Margaret (2013). Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0999-3.

- Paskoff, Paul F. (2008). "Measures of War: A Quantitative Examination of the Civil War's Destructiveness in the Confederacy". Civil War History. 54 (1): 35–62. doi:10.1353/cwh.2008.0007.

- Ezell, John Samuel (1963). The South since 1865. New York: Macmillan. pp. 27–28.

- Stover, John F. (1955). The Railroads of the South, 1865-1900: A Study in Finance and Control. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Moore, A. B. (1935). "Railroad Building in Alabama During the Reconstruction Period". Journal of Southern History. 1 (4): 421–441. doi:10.2307/2191774. JSTOR 2191774.

- Summers, Mark Wahlgren (1984). Railroads, Reconstruction, and the Gospel of Prosperity: Aid Under the Radical Republicans, 1865–1877. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04695-6.

- Hackney, Sheldon (1972). "Origins of the New South in Retrospect". Journal of Southern History. 38 (2): 191–216 [quote at p. 191]. doi:10.2307/2206441. JSTOR 2206441.

- Logan (1997). The Betrayal of the Negro from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-306-80758-0.

- Wright, Richard (1945). "9". Black Boy. New York City: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 0-06-113024-9.

- Estes, Steve (2005). I Am a Man! Race, Manhood, and the Civil Rights Movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-5593-6.

- Nicholas Lemann, The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America (2011)

- Richard Knight, The Blues Highway: New Orleans to Chicago: a Travel and Music Guide (2003)

- Bernadette Pruitt (2013). The Other Great Migration: The Movement of Rural African Americans to Houston, 1900-1941. Texas A&M University Press. p. 287. ISBN 9781623490034.

- "Census Regions and Divisions of the United States" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013.

- Whitten, David O. (2010). "The Depression of 1893".

- Hahn, Steven (2005). A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration. Cambridge: Belknap Press. pp. 425–426. ISBN 0-674-01765-X.

- Sharon Monteith, ed. (2013). The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the American South. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9781107036789.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- U.S. Department of Commerce (1930). Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1930. Washington. pp. 113–115.

- Odum, Howard (1936). Southern Regions of the United States. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 100.

- Coelho, Philip R. P.; McGuire, Robert A. (2006). "Racial Differences in Disease Susceptibilities: Intestinal Worm Infections in the Early Twentieth-Century American South". Social History of Medicine. 19 (3): 461–482. doi:10.1093/shm/hkl047. indicates 56% of the whites suffered from worms, and 20% of the blacks.

- Woodward, C. Vann (1951). The Origins of the New South, 1877–1913. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press

- Tindall, George B. (1967). The Emergence of the New South, 1913–1945. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-0010-2.

- Harold D, Woodman, "Economic Reconstruction and the Rise of the New South, 1865-1900" in John B. Boles, and Evelyn Thomas Nolen, eds., Interpreting Southern history: Historiographical essays in honor of Sanford W. Higginbotham (LSU Press, 1987) pp. 254–307, quoting pp 273-274.

- Cobb, James C. (2011). The South and America Since World War II. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516650-7.

- Cobb, James C.; Stueck, William (2005). Globalization and the American South. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-2648-8.

- Dennis, Michael (2009). The New Economy and the Modern South. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-3291-7.

- Black, Earl (2003). "The Republican Surge". The Rise of Southern Republicans. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00728-X.

- Kirby, Jack Temple (1986). Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920–1960. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1300-X.

- Stanonis, Anthony J. (2008). Dixie Emporium: Tourism, Foodways, and Consumer Culture in the American South. Athens: University of Georgia Press. pp. 120–147 on Branson. ISBN 978-0-8203-2951-2.

- Cooper, Christopher A.; Knotts, H. Gibbs (2010). "Declining Dixie: Regional Identification in the Modern American South". Social Forces. 88 (3): 1083–1101. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0284.

- Rice, Tom W.; McLean, William P.; Larsen, Amy J. (2002). "Southern Distinctiveness over Time: 1972–2000". American Review of Politics. 23: 193–220. doi:10.15763/issn.2374-7781.2002.23.0.193-220.

- Cooper, Christopher A.; Knotts, H. Gibbs (2004). "Defining Dixie: A State-Level Measure of the Modern Political South". American Review of Politics. 25 (2): 25–39. doi:10.15763/issn.2374-7781.2004.25.0.25-39.

- Reed, John Shelton (1982). One South: An Ethnic Approach to Regional Culture. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8071-1003-5.

- Egnal, Marc (1996). Divergent Paths: How Culture and Institutions have shaped North American Growth. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0-19-509866-8.

- Mark, Rebecca; Vaughan, Robert C. (2004). The South. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-313-32734-3.

- Cooper, Christopher A.; Knotts, H. Gibbs (2010). "Declining Dixie: Regional Identification in the Modern American South". Social Forces. 88 (3): 1083–1101 [p. 1084]. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0284.

- Cooper, Christopher A.; Knotts, H. Gibbs, eds. (2008). The New Politics of North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3191-5.

- Ayers, Edward L. (2005). What Caused the Civil War? Reflections on the South and Southern History. New York: Norton. p. 46. ISBN 0-393-05947-2.

- Hirsh, Michael (April 25, 2008). "How the South Won (This) Civil War". Newsweek. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

Further reading

- Abernethy, Thomas P. The South in the New Nation, 1789–1819 (LSU Press, 1961)

- Alden, John R. The South in the Revolution, 1763–1789 (LSU Press, 1957)

- Ayers; Edward L. The Promise of the New South: Life after Reconstruction (Oxford University Press, 1993) online edition

- Bartley, Numan V. The New South, 1945–1980 (LSU Press, 1996)

- Best, John Hardin. "Education in the Forming of the American South". History of Education Quarterly (1996) 36#1 pp. 39–51 in JSTOR

- Clark, Thomas D. Pills, Petticoats, and Plows: The Southern Country Store (1944).

- Cooper, William J., Thomas E. Terrill and Christopher Childers. The American South (2 vol. 5th ed. 2016), 1160 pp

- Craven, Avery O. The Growth of Southern Nationalism, 1848–1861 (LSU, 1953)

- Craven, Wesley Frank. The Southern Colonies in the Seventeenth Century, 1607–1689. (LSU, 1949)

- Coulter, E. Merton. The Confederate States of America, 1861–1865. (LSU, 1962)

- Coulter, E. Merton. The South During Reconstruction, 1865–1877. (LSU, 1947)

- Current, Richard, ed. Encyclopedia of the Confederacy (4 vol 1995); 1,474 entries by 330 scholars.

- Davis, William C. (2003). Look Away! A History of the Confederate States of America. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-86585-8.

- Hesseltine; William B. A History of the South, 1607-1936 Prentice-Hall, 1936 online edition

- Hill, Samuel S. et al. eds. Encyclopedia of Religion in the South (2005)

- Hubbell; Jay B. The South in American Literature, 1607-1900 Duke University Press, 1973

- Key, V.O. Southern Politics in State and Nation (1951) classic political analysis, state by state. online free to borrow

- Kirby, Jack Temple. Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920-1960 (LSU Press, 1986) major scholarly survey with detailed bibliography; online free to borrow.

- Lamis, Alexander P. ed. Southern Politics in the 1990s (LSU Press, 1999).

- Logan, Rayford, The Betrayal of the Negro from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson, (1997). (This is an expanded edition of Logan, The Negro in American Life and Thought, The Nadir, 1877–1901 (1954))

- Mark, Rebecca, and Rob Vaughan. The South: The Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Regional Cultures (2004), post 1945 society

- Marrs, Aaron W. Railroads in the Old South: Pursuing Progress in a Slave Society (2009)

- Moreland; Laurence W. et al. Blacks in Southern Politics Praeger Publishers, 1987 online edition

- Paterson, Thomas G. ed. (1999). Major Problems in the History of the American South. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-87139-5.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) readings from primary and secondary sources

- Richter, William L. The A to Z of the Old South (2009), a short scholarly encyclopedia

- Shafer, Byron E. and Richard Johnston, eds. The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South (2009) excerpt and text search

- Sydnor, Charles W. The Development of Southern Sectionalism, 1819–1848. (LSU Press, 1964), Broad ranging history of the region

- Tindall, George B. The Emergence of the New South, 1913–1945 (LSU Press, 1967) online