Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War[nb 1] was a civil war in Finland in 1918 fought for the leadership and control of Finland during the country's transition from a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire to an independent state. The clashes took place in the context of the national, political, and social turmoil caused by World War I (Eastern Front) in Europe. The war was fought between the Reds, led by a section of the Social Democratic Party, and the Whites, conducted by the conservative-based Senate and the German Imperial Army. The paramilitary Red Guards, composed of industrial and agrarian workers, controlled the cities and industrial centres of southern Finland. The paramilitary White Guards, composed of farmers, along with middle-class and upper-class social strata, controlled rural central and northern Finland.

In the years before the conflict, Finnish society had experienced rapid population growth, industrialisation, pre-urbanisation and the rise of a comprehensive labour movement. The country's political and governmental systems were in an unstable phase of democratisation and modernisation. The socio-economic condition and education of the population had gradually improved, as well as national thinking and cultural life had awakened.

World War I led to the collapse of the Russian Empire, causing a power vacuum in Finland, and a subsequent struggle for dominance led to militarisation and an escalating crisis between the left-leaning labour movement and the conservatives. The Reds carried out an unsuccessful general offensive in February 1918, supplied with weapons by Soviet Russia. A counteroffensive by the Whites began in March, reinforced by the German Empire's military detachments in April. The decisive engagements were the Battles of Tampere and Vyborg (Finnish: Viipuri; Swedish: Viborg), won by the Whites, and the Battles of Helsinki and Lahti, won by German troops, leading to overall victory for the Whites and the German forces. Political violence became a part of this warfare. Around 12,500 Red prisoners of war died of malnutrition and disease in camps. About 39,000 people, of whom 36,000 were Finns, perished in the conflict.

In the aftermath, the Finns passed from Russian governance to the German sphere of influence with a plan to establish a German-led Finnish monarchy. The scheme was cancelled with the defeat of Germany in World War I and Finland instead emerged as an independent, democratic republic. The Civil War divided the nation for decades. Finnish society was reunited through social compromises based on a long-term culture of moderate politics and religion and the post-war economic recovery.

Background

International politics

The main factor behind the Finnish Civil War was a political crisis arising out of World War I. Under the pressures of the Great War, the Russian Empire collapsed, leading to the February and October Revolutions in 1917. This breakdown caused a power vacuum and a subsequent struggle for power in Eastern Europe. Russia's Grand Duchy of Finland (1809–1917), became embroiled in the turmoil. Geopolitically less important than the continental Moscow–Warsaw gateway, Finland, isolated by the Baltic Sea was a peaceful side front until early 1918. The war between the German Empire and Russia had only indirect effects on the Finns. Since the end of the 19th century, the Grand Duchy had become a vital source of raw materials, industrial products, food and labour for the growing Imperial Russian capital Petrograd (modern Saint Petersburg), and World War I emphasised that role. Strategically, the Finnish territory was the less important northern section of the Estonian–Finnish gateway and a buffer zone to and from Petrograd through the Narva area, the Gulf of Finland and the Karelian Isthmus.[6]

The German Empire saw Eastern Europe—primarily Russia—as a major source of vital products and raw materials, both during World War I and for the future. Her resources overstretched by the two-front war, Germany attempted to divide Russia by providing financial support to revolutionary groups, such as the Bolsheviks and the Socialist Revolutionary Party, and to radical, separatist factions, such as the Finnish national activist movement leaning toward Germanism. Between 30 and 40 million marks were spent on this endeavour. Controlling the Finnish area would allow the Imperial German Army to penetrate Petrograd and the Kola Peninsula, an area rich in raw materials for the mining industry. Finland possessed large ore reserves and a well-developed forest industry.[7]

From 1809 to 1898, a period called Pax Russica, the peripheral authority of the Finns gradually increased, and Russo-Finnish relations were exceptionally peaceful in comparison with other parts of the Russian Empire. Russia's defeat in the Crimean War in the 1850s led to attempts to speed up the modernisation of the country. This caused more than 50 years of economic, industrial, cultural and educational progress in the Grand Duchy of Finland, including an improvement in the status of the Finnish language. All this encouraged Finnish nationalism and cultural unity through the birth of the Fennoman movement, which bound the Finns to the domestic administration and led to the idea that the Grand Duchy was an increasingly autonomous state of the Russian Empire.[8]

In 1899, the Russian Empire initiated a policy of integration through the Russification of Finland. The strengthened, pan-slavist central power tried to unite the "Russian Multinational Dynastic Union" as the military and strategic situation of Russia became more perilous due to the rise of Germany and Japan. Finns called the increased military and administrative control, "the First Period of Oppression", and for the first time Finnish politicians drew up plans for disengagement from Russia or sovereignty for Finland. In the struggle against integration, activists drawn from sections of the working class and the Swedish-speaking intelligentsia carried out terrorist acts. During World War I and the rise of Germanism, the pro-Swedish Svecomans began their covert collaboration with Imperial Germany and, from 1915 to 1917, a Jäger (Finnish: jääkäri; Swedish: jägar) battalion consisting of 1,900 Finnish volunteers was trained in Germany.[9]

Domestic politics

The major reasons for rising political tensions among Finns were the autocratic rule of the Russian czar and the undemocratic class system of the estates of the realm. The latter system originated in the regime of the Swedish Empire that preceded Russian governance and divided the Finnish people economically, socially and politically. Finland's population grew rapidly in the nineteenth century (from 860,000 in 1810 to 3,130,000 in 1917), and a class of agrarian and industrial workers, as well as crofters, emerged over the period. The Industrial Revolution was rapid in Finland, though it started later than in the rest of Western Europe. Industrialisation was financed by the state and some of the social problems associated with the industrial process were diminished by the administration's actions. Among urban workers, socio-economic problems steepened during periods of industrial depression. The position of rural workers worsened after the end of the nineteenth century, as farming became more efficient and market-oriented, and the development of industry was insufficiently vigorous to fully utilise the rapid population growth of the countryside.[10]

The difference between Scandinavian-Finnish (Finno-Ugric peoples) and Russian-Slavic culture affected the nature of Finnish national integration. The upper social strata took the lead and gained domestic authority from the Russian czar in 1809. The estates planned to build an increasingly autonomous Finnish state, led by the elite and the intelligentsia. The Fennoman movement aimed to include the common people in a non-political role; the labour movement, youth associations and the temperance movement were initially led "from above".[11]

Between 1870 and 1916 industrialisation gradually improved social conditions and the self-confidence of workers, but while the standard of living of the common people rose in absolute terms, the rift between rich and poor deepened markedly. The commoners' rising awareness of socio-economic and political questions interacted with the ideas of socialism, social liberalism and nationalism. The workers' initiatives and the corresponding responses of the dominant authorities intensified social conflict in Finland.[12]

.jpg)

The Finnish labour movement, which emerged at the end of the nineteenth century from temperance, religious movements and Fennomania, had a Finnish nationalist, working-class character. From 1899 to 1906, the movement became conclusively independent, shedding the paternalistic thinking of the Fennoman estates, and it was represented by the Finnish Social Democratic Party, established in 1899. Workers' activism was directed both toward opposing Russification and in developing a domestic policy that tackled social problems and responded to the demand for democracy. This was a reaction to the domestic dispute, ongoing since the 1880s, between the Finnish nobility-bourgeoisie and the labour movement concerning voting rights for the common people.[13]

Despite their obligations as obedient, peaceful and non-political inhabitants of the Grand Duchy (who had, only a few decades earlier, accepted the class system as the natural order of their life), the commoners began to demand their civil rights and citizenship in Finnish society. The power struggle between the Finnish estates and the Russian administration gave a concrete role model and free space for the labour movement. On the other side, due to an at-least century-long tradition and experience of administrative authority, the Finnish elite saw itself as the inherent natural leader of the nation.[14] The political struggle for democracy was solved outside Finland, in international politics: the Russian Empire's failed 1904–1905 war against Japan led to the 1905 Revolution in Russia and to a general strike in Finland. In an attempt to quell the general unrest, the system of estates was abolished in the Parliamentary Reform of 1906. The general strike increased support for the social democrats substantially. The party encompassed a higher proportion of the population than any other socialist movement in the world.[15]

The Reform of 1906 was a giant leap towards the political and social liberalisation of the common Finnish people because the Russian House of Romanov had been the most autocratic and conservative ruler in Europe. The Finns adopted a unicameral parliamentary system, the Parliament of Finland (Finnish: eduskunta; Swedish: riksdag) with universal suffrage. The number of voters increased from 126,000 to 1,273,000, including female citizens. The reform led to the social democrats obtaining about fifty percent of the popular vote, but the Czar regained his authority after the crisis of 1905. Subsequently, during the more severe programme of Russification, called "the Second Period of Oppression" by the Finns, the Czar neutralised the power of the Finnish Parliament between 1908 and 1917. He dissolved the assembly, ordered parliamentary elections almost annually, and determined the composition of the Finnish Senate, which did not correlate with the Parliament.[16]

The capacity of the Finnish Parliament to solve socio-economic problems was stymied by confrontations between the largely uneducated commoners and the former estates. Another conflict festered as employers denied collective bargaining and the right of the labour unions to represent workers. The parliamentary process disappointed the labour movement, but as dominance in the Parliament and legislation was the workers' most likely way to obtain a more balanced society, they identified themselves with the state. Overall domestic politics led to a contest for leadership of the Finnish state during the ten years before the collapse of the Russian Empire.[17]

February Revolution

Build-up

The Second Period of Russification was halted on 15 March 1917 by the February Revolution, which removed the czar, Nicholas II. The collapse of Russia was caused by military defeats, war-weariness against the duration and hardships of the Great War, and the collision between the most conservative regime in Europe and a Russian people desiring modernisation. The Czar's power was transferred to the State Duma (Russian Parliament) and the right-wing Provisional Government, but this new authority was challenged by the Petrograd Soviet (city council), leading to dual power in the country.[18]

The autonomous status of 1809–1899 was returned to the Finns by the March 1917 manifesto of the Russian Provisional Government. For the first time in history, de facto political power existed in the Parliament of Finland. The political left, consisting mainly of social democrats, covered a wide spectrum from moderate to revolutionary socialists. The political right was even more diverse, ranging from social liberals and moderate conservatives to rightist conservative elements. The four main parties were:

- The conservative Finnish Party;

- the Young Finnish Party, which included both liberals and conservatives, with the liberals divided between social liberals and economic liberals;

- the social reformist, centrist Agrarian League, which drew its support mainly from peasants with small or mid-sized farms; and

- the conservative Swedish People's Party, which sought to retain the rights of the former nobility and the Swedish-speaking minority of Finland.[19]

During 1917, a power struggle and social disintegration interacted. The collapse of Russia induced a chain reaction of disintegration, starting from the government, military and economy, and spreading to all fields of society, such as local administration, workplaces and to individual citizens. The social democrats wanted to retain the civil rights already achieved and to increase the socialists' power over society. The conservatives feared the loss of their long-held socio-economic dominance. Both factions collaborated with their equivalents in Russia, deepening the split in the nation.[20]

The Social Democratic Party gained an absolute majority in the parliamentary elections of 1916. A new Senate was formed in March 1917 by Oskari Tokoi, but it did not reflect the socialists' large parliamentary majority: it comprised six social democrats and six non-socialists. In theory, the Senate consisted of a broad national coalition, but in practice (with the main political groups unwilling to compromise and top politicians remaining outside of it), it proved unable to solve any major Finnish problem. After the February Revolution, political authority descended to the street level: mass meetings, strike organisations and worker-soldier councils on the left and to active organisations of employers on the right, all serving to undermine the authority of the state.[21]

The February Revolution halted the Finnish economic boom caused by the Russian war-economy. The collapse in business led to unemployment and high inflation, but the employed workers gained an opportunity to resolve workplace problems. The commoners' call for the eight-hour working day, better working conditions and higher wages led to demonstrations and large-scale strikes in industry and agriculture.[22]

While the Finns had specialised in milk and butter production, the bulk of the food supply for the country depended on cereals produced in southern Russia. The cessation of cereal imports from disintegrating Russia led to food shortages in Finland. The Senate responded by introducing rationing and price controls. The farmers resisted the state control and thus a black market, accompanied by sharply rising food prices, formed. As a consequence, export to the free market of the Petrograd area increased. Food supply, prices and, in the end, the fear of starvation became emotional political issues between farmers and urban workers, especially those who were unemployed. Common people, their fears exploited by politicians and an incendiary, polarised political media, took to the streets. Despite the food shortages, no actual large-scale starvation hit southern Finland before the civil war and the food market remained a secondary stimulator in the power struggle of the Finnish state.[23]

Contest for leadership

The passing of the Tokoi Senate bill called the "Law of Supreme Power" (Finnish: laki Suomen korkeimman valtiovallan käyttämisestä, more commonly known as valtalaki; Swedish: maktlagen) in July 1917, triggered one of the key crises in the power struggle between the social democrats and the conservatives. The fall of the Russian Empire opened the question of who would hold sovereign political authority in the former Grand Duchy. After decades of political disappointment, the February Revolution offered the Finnish social democrats an opportunity to govern; they held the absolute majority in Parliament. The conservatives were alarmed by the continuous increase of the socialists' influence since 1899, which reached a climax in 1917.[24]

The "Law of Supreme Power" incorporated a plan by the socialists to substantially increase the authority of Parliament, as a reaction to the non-parliamentary and conservative leadership of the Finnish Senate between 1906 and 1916. The bill furthered Finnish autonomy in domestic affairs: the Russian Provisional Government was only allowed the right to control Finnish foreign and military policies. The Act was adopted with the support of the Social Democratic Party, the Agrarian League, part of the Young Finnish Party and some activists eager for Finnish sovereignty. The conservatives opposed the bill and some of the most right-wing representatives resigned from Parliament.[25]

In Petrograd, the social democrats' plan had the backing of the Bolsheviks. They had been plotting a revolt against the Provisional Government since April 1917, and pro-Soviet demonstrations during the July Days brought matters to a head. The Helsinki Soviet and the Regional Committee of the Finnish Soviets, led by the Bolshevik Ivar Smilga, both pledged to defend the Finnish Parliament, were it threatened with attack.[26] However, the Provisional Government still had sufficient support in the Russian army to survive and as the street movement waned, Vladimir Lenin fled to Karelia. In the aftermath of these events, the "Law of Supreme Power" was overruled and the social democrats eventually backed down; more Russian troops were sent to Finland and, with the co-operation and insistence of the Finnish conservatives, Parliament was dissolved and new elections announced.[27]

In the October 1917 elections, the social democrats lost their absolute majority, which radicalised the labour movement and decreased support for moderate politics. The crisis of July 1917 did not bring about the Red Revolution of January 1918 on its own, but together with political developments based on the commoners' interpretation of the ideas of Fennomania and socialism, the events favoured a Finnish revolution. In order to win power, the socialists had to overcome Parliament.[28]

The February Revolution resulted in a loss of institutional authority in Finland and the dissolution of the police force, creating fear and uncertainty. In response, both the right and left assembled their own security groups, which were initially local and largely unarmed. By late 1917, following the dissolution of Parliament, in the absence of a strong government and national armed forces, the security groups began assuming a broader and more paramilitary character. The Civil Guards (Finnish: suojeluskunnat; Swedish: skyddskåren; lit. 'protection corps') and the later White Guards (Finnish: valkokaartit; Swedish: vita gardet) were organised by local men of influence: conservative academics, industrialists, major landowners, and activists. The Workers' Order Guards (Finnish: työväen järjestyskaartit; Swedish: arbetarnas ordningsgardet) and the Red Guards (Finnish: punakaartit; Swedish: röda gardet) were recruited through the local social democratic party sections and from the labour unions.[29]

October Revolution

The Bolsheviks' and Vladimir Lenin's October Revolution of 7 November 1917 transferred political power in Petrograd to the radical, left-wing socialists. The German government's decision to arrange safe-conduct for Lenin and his comrades from exile in Switzerland to Petrograd in April 1917, was a success. An armistice between Germany and the Bolshevik regime came into force on 6 December and peace negotiations began on 22 December 1917 at Brest-Litovsk.[30]

November 1917 became another watershed in the 1917–1918 rivalry for the leadership of Finland. After the dissolution of the Finnish Parliament, polarisation between the social democrats and the conservatives increased markedly and the period witnessed the appearance of political violence. An agricultural worker was shot during a local strike on 9 August 1917 at Ypäjä and a Civil Guard member was killed in a local political crisis at Malmi on 24 September.[31] The October Revolution disrupted the informal truce between the Finnish non-socialists and the Russian Provisional Government. After political wrangling over how to react to the revolt, the majority of the politicians accepted a compromise proposal by Santeri Alkio, the leader of the Agrarian League. Parliament seized the sovereign power in Finland on 15 November 1917 based on the socialists' "Law of Supreme Power" and ratified their proposals of an eight-hour working day and universal suffrage in local elections, from July 1917.[32]

.jpg)

The purely non-socialist, conservative-led government of Pehr Evind Svinhufvud was appointed on 27 November. This nomination was both a long-term aim of the conservatives and a response to the challenges of the labour movement during November 1917. Svinhufvud's main aspirations were to separate Finland from Russia, to strengthen the Civil Guards, and to return a part of Parliament's new authority to the Senate.[33] There were 149 Civil Guards on 31 August 1917 in Finland, counting local units and subsidiary White Guards in towns and rural communes; 251 on 30 September; 315 on 31 October; 380 on 30 November and 408 on 26 January 1918. The first attempt at serious military training among the Guards was the establishment of a 200-strong cavalry school at the Saksanniemi estate in the vicinity of the town of Porvoo, in September 1917. The vanguard of the Finnish Jägers and German weaponry arrived in Finland during October–November 1917 on the Equity freighter and the German U-boat UC-57; around 50 Jägers had returned by the end of 1917.[34]

After political defeats in July and October 1917, the social democrats put forward an uncompromising program called "We Demand" (Finnish: Me vaadimme; Swedish: Vi kräver) on 1 November, in order to push for political concessions. They insisted upon a return to the political status before the dissolution of Parliament in July 1917, disbandment of the Civil Guards and elections to establish a Finnish Constituent Assembly. The program failed and the socialists initiated a general strike during 14–19 November to increase political pressure on the conservatives, who had opposed the "Law of Supreme Power" and the parliamentary proclamation of sovereign power on 15 November.[35]

Revolution became the goal of the radicalised socialists after the loss of political control, and events in November 1917 offered momentum for a socialist uprising. In this phase, Lenin and Joseph Stalin, under threat in Petrograd, urged the social democrats to take power in Finland. The majority of Finnish socialists were moderate and preferred parliamentary methods, prompting the Bolsheviks to label them "reluctant revolutionaries". The reluctance diminished as the general strike appeared to offer a major channel of influence for the workers in southern Finland. The strike leadership voted by a narrow majority to start a revolution on 16 November, but the uprising had to be called off the same day due to the lack of active revolutionaries to execute it.[36]

.jpg)

At the end of November 1917, the moderate socialists among the social democrats won a second vote over the radicals in a debate over revolutionary versus parliamentary means, but when they tried to pass a resolution to completely abandon the idea of a socialist revolution, the party representatives and several influential leaders voted it down. The Finnish labour movement wanted to sustain a military force of its own and to keep the revolutionary road open, too. The wavering Finnish socialists disappointed V. I. Lenin and in turn, he began to encourage the Finnish Bolsheviks in Petrograd.[37]

Among the labour movement, a more marked consequence of the events of 1917 was the rise of the Workers' Order Guards. There were 20–60 separate guards between 31 August and 30 September 1917, but on 20 October, after defeat in parliamentary elections, the Finnish labour movement proclaimed the need to establish more worker units. The announcement led to a rush of recruits: on 31 October the number of guards was 100–150; 342 on 30 November 1917 and 375 on 26 January 1918. Since May 1917, the paramilitary organisations of the left had grown in two phases, the majority of them as Workers' Order Guards. The minority were Red Guards, these were partly underground groups formed in industrialised towns and industrial centres, such as Helsinki, Kotka and Tampere, based on the original Red Guards that had been formed during 1905–1906 in Finland.[38]

The presence of the two opposing armed forces created a state of dual power and divided sovereignty on Finnish society. The decisive rift between the guards broke out during the general strike: the Reds executed several political opponents in southern Finland and the first armed clashes between the Whites and Reds took place. In total, 34 casualties were reported. Eventually, the political rivalries of 1917 led to an arms race and an escalation towards civil war.[39]

Independence of Finland

The disintegration of Russia offered Finns an historic opportunity to gain national independence. After the October Revolution, the conservatives were eager for secession from Russia in order to control the left and minimise the influence of the Bolsheviks. The socialists were skeptical about sovereignty under conservative rule, but they feared a loss of support among nationalistic workers, particularly after having promised increased national liberty through the "Law of Supreme Power". Eventually, both political factions supported an independent Finland, despite strong disagreement over the composition of the nation's leadership.[40]

Nationalism had become a "civic religion" in Finland by the end of nineteenth century, but the goal during the general strike of 1905 was a return to the autonomy of 1809–1898, not full independence. In comparison to the unitary Swedish regime, the domestic power of Finns had increased under the less uniform Russian rule. Economically, the Grand Duchy of Finland benefited from having an independent domestic state budget, a central bank with national currency, the markka (deployed 1860), and customs organisation and the industrial progress of 1860–1916. The economy was dependent on the huge Russian market and separation would disrupt the profitable Finnish financial zone. The economic collapse of Russia and the power struggle of the Finnish state in 1917 were among the key factors that brought sovereignty to the fore in Finland.[41]

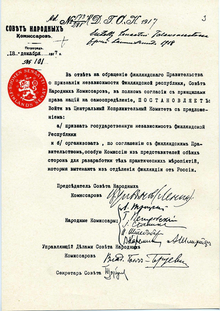

Svinhufvud's Senate introduced Finland's Declaration of Independence on 4 December 1917 and Parliament adopted it on 6 December. The social democrats voted against the Senate's proposal, while presenting an alternative declaration of sovereignty. The establishment of an independent state was not a guaranteed conclusion for the small Finnish nation. Recognition by Russia and other great powers was essential; Svinhufvud accepted that he had to negotiate with Lenin for the acknowledgement. The socialists, having been reluctant to enter talks with the Russian leadership in July 1917, sent two delegations to Petrograd to request that Lenin approve Finnish sovereignty.[43]

In December 1917, Lenin was under intense pressure from the Germans to conclude peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk and the Bolsheviks' rule was in crisis, with an inexperienced administration and the demoralised army facing powerful political and military opponents. Lenin calculated that the Bolsheviks could fight for central parts of Russia but had to give up some peripheral territories, including Finland in the geopolitically less important north-western corner. As a result, Svinhufvud's delegation won Lenin's concession of sovereignty on 31 December 1917.[44]

By the beginning of the Civil War, Austria-Hungary, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland had recognised Finnish independence. The United Kingdom and United States did not approve it; they waited and monitored the relations between Finland and Germany (the main enemy of the Allies), hoping to override Lenin's regime and to get Russia back into the war against the German Empire. In turn, the Germans hastened Finland's separation from Russia so as to move the country to within their sphere of influence.[45]

Warfare

.jpg)

Escalation

The final escalation towards war began in early January 1918, as each military or political action of the Reds or the Whites resulted in a corresponding counteraction by the other. Both sides justified their activities as defensive measures, particularly to their own supporters. On the left, the vanguard of the movement was the urban Red Guards from Helsinki, Kotka and Turku; they led the rural Reds and convinced the socialist leaders who wavered between peace and war to support the revolution. On the right, the vanguard was the Jägers, who had transferred to Finland, and the volunteer Civil Guards of southwestern Finland, southern Ostrobothnia and Vyborg province in the southeastern corner of Finland. The first local battles were fought during 9–21 January 1918 in southern and southeastern Finland, mainly to win the arms race and to control Vyborg (Finnish: Viipuri; Swedish: Viborg).[46]

On 12 January 1918, Parliament authorised the Svinhufvud Senate to establish internal order and discipline on behalf of the state. On 15 January, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, a former Finnish general of the Imperial Russian Army, was appointed the commander-in-chief of the Civil Guards. The Senate appointed the Guards, henceforth called the White Guards, as the White Army of Finland. Mannerheim placed his Headquarters of the White Army in the Vaasa–Seinäjoki area. The White Order to engage was issued on 25 January. The Whites gained weaponry by disarming Russian garrisons during 21–28 January, in particular in southern Ostrobothnia.[47]

The Red Guards, led by Ali Aaltonen, refused to recognise the Whites' hegemony and established a military authority of their own. Aaltonen installed his headquarters in Helsinki and nicknamed it Smolna echoing the Smolny Institute, the Bolsheviks' headquarters in Petrograd. The Red Order of Revolution was issued on 26 January, and a red lantern, a symbolic indicator of the uprising, was lit in the tower of the Helsinki Workers' House. A large-scale mobilisation of the Reds began late in the evening of 27 January, with the Helsinki Red Guard and some of the Guards located along the Vyborg-Tampere railway having been activated between 23 and 26 January, in order to safeguard vital positions and escort a heavy railroad shipment of Bolshevik weapons from Petrograd to Finland. White troops tried to capture the shipment: 20–30 Finns, Red and White, died in the Battle of Kämärä at the Karelian Isthmus on 27 January 1918.[48] The Finnish rivalry for power had culminated.[49]

Opposing parties

Red Finland and White Finland

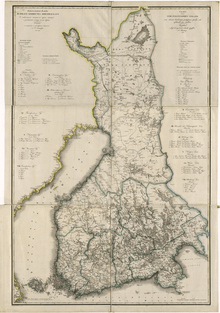

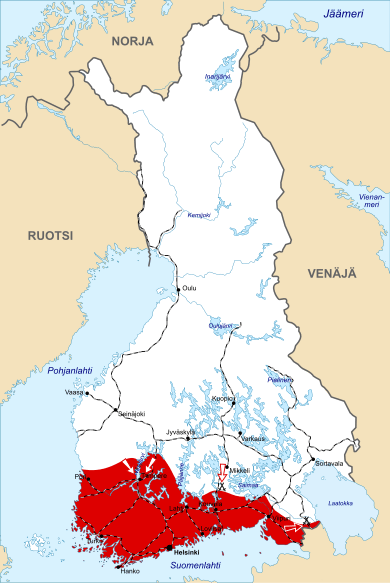

At the beginning of the war, a discontinuous front line ran through southern Finland from west to east, dividing the country into White Finland and Red Finland. The Red Guards controlled the area to the south, including nearly all the major towns and industrial centres, along with the largest estates and farms with the highest numbers of crofters and tenant farmers. The White Army controlled the area to the north, which was predominantly agrarian and contained small or medium-sized farms and tenant farmers. The number of crofters was lower and they held a better social status than those in the south. Enclaves of the opposing forces existed on both sides of the front line: within the White area lay the industrial towns of Varkaus, Kuopio, Oulu, Raahe, Kemi and Tornio; within the Red area lay Porvoo, Kirkkonummi and Uusikaupunki. The elimination of these strongholds was a priority for both armies in February 1918.[50]

Red Finland was led by the People's Delegation (Finnish: kansanvaltuuskunta; Swedish: folkdelegationen), established on 28 January 1918 in Helsinki. The delegation sought democratic socialism based on the Finnish Social Democratic Party's ethos; their visions differed from Lenin's dictatorship of the proletariat. Otto Ville Kuusinen formulated a proposal for a new constitution, influenced by those of Switzerland and the United States. With it, political power was to be concentrated to Parliament, with a lesser role for a government. The proposal included a multi-party system; freedom of assembly, speech and press; and the use of referenda in political decision-making. In order to ensure the authority of the labour movement, the common people would have a right to permanent revolution. The socialists planned to transfer a substantial part of property rights to the state and local administrations.[51]

In foreign policy, Red Finland leaned on Bolshevist Russia. A Red-initiated Finno–Russian treaty and peace agreement was signed on 1 March 1918, where Red Finland was called the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (Finnish: Suomen sosialistinen työväentasavalta; Swedish: Finlands socialistiska arbetarrepublik). The negotiations for the treaty implied that –as in World War I in general– nationalism was more important for both sides than the principles of international socialism. The Red Finns did not simply accept an alliance with the Bolsheviks and major disputes appeared, for example, over the demarcation of the border between Red Finland and Soviet Russia. The significance of the Russo–Finnish Treaty evaporated quickly due to the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between the Bolsheviks and the German Empire on 3 March 1918.[52]

Lenin's policy on the right of nations to self-determination aimed at preventing the disintegration of Russia during the period of military weakness. He assumed that in war-torn, splintering Europe, the proletariat of free nations would carry out socialist revolutions and unite with Soviet Russia later. The majority of the Finnish labour movement supported Finland's independence. The Finnish Bolsheviks, influential, though few in number, favoured annexation of Finland by Russia.[53]

The government of White Finland, Pehr Evind Svinhufvud's first senate, was called the Vaasa Senate after its relocation to the safer west-coast city of Vaasa, which acted as the capital of the Whites from 29 January to 3 May 1918. In domestic policy, the White Senate's main goal was to return the political right to power in Finland. The conservatives planned a monarchist political system, with a lesser role for Parliament. A section of the conservatives had always supported monarchy and opposed democracy; others had approved of parliamentarianism since the revolutionary reform of 1906, but after the crisis of 1917–1918, concluded that empowering the common people would not work. Social liberals and reformist non-socialists opposed any restriction of parliamentarianism. They initially resisted German military help, but the prolonged warfare changed their stance.[54]

In foreign policy, the Vaasa Senate relied on the German Empire for military and political aid. Their objective was to defeat the Finnish Reds; end the influence of Bolshevist Russia in Finland and expand Finnish territory to East Karelia, a geopolitically significant home to people speaking Finno-Ugric languages. The weakness of Russia inspired an idea of Greater Finland among the expansionist factions of both the right and left: the Reds had claims concerning the same areas. General Mannerheim agreed on the need to take over East Karelia and to request German weapons, but opposed actual German intervention in Finland. Mannerheim recognised the Red Guards' lack of combat skill and trusted in the abilities of the German-trained Finnish Jägers. As a former Russian army officer, Mannerheim was well aware of the demoralisation of the Russian army. He co-operated with White-aligned Russian officers in Finland and Russia.[55]

Soldiers and weapons

The number of Finnish troops on each side varied from 70,000 to 90,000 and both had around 100,000 rifles, 300–400 machine guns and a few hundred cannons. While the Red Guards consisted mostly of volunteers, with wages paid at the beginning of the war, the White Army consisted predominantly of conscripts with 11,000–15,000 volunteers. The main motives for volunteering were socio-economic factors, such as salary and food, as well as idealism and peer pressure. The Red Guards included 2,600 women, mostly girls recruited from the industrial centres and cities of southern Finland. Urban and agricultural workers constituted the majority of the Red Guards, whereas land-owning farmers and well-educated people formed the backbone of the White Army.[57] Both armies used child soldiers, mainly between 14 and 17 years of age. The use of juvenile soldiers was not rare in World War I; children of the time were under the absolute authority of adults and were not shielded against exploitation.[58]

Rifles and machine guns from Imperial Russia were the main armaments of the Reds and the Whites. The most commonly used rifle was the Russian 7.62 mm (0.3 in) Mosin–Nagant Model 1891. In total, around ten different rifle models were in service, causing problems for ammunition supply. The Maxim gun was the most-used machine gun, along with the less-used M1895 Colt–Browning, Lewis and Madsen guns. The machine guns caused a substantial part of the casualties in combat. Russian field guns were mostly used with direct fire.[59]

The Civil War was fought primarily along railways; vital means for transporting troops and supplies, as well for using armoured trains, equipped with light cannons and heavy machine guns. The strategically most important railway junction was Haapamäki, approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) northeast of Tampere, connecting eastern and western Finland and as well as southern and northern Finland. Other critical junctions included Kouvola, Riihimäki, Tampere, Toijala and Vyborg. The Whites captured Haapamäki at the end of January 1918, leading to the Battle of Vilppula.[60]

Red Guards and Soviet troops

The Finnish Red Guards seized the early initiative in the war by taking control of Helsinki on 28 January 1918 and by undertaking a general offensive lasting from February till early March 1918. The Reds were relatively well-armed, but a chronic shortage of skilled leaders, both at the command level and in the field, left them unable to capitalise on this momentum, and most of the offensives came to nothing. The military chain of command functioned relatively well at company and platoon level, but leadership and authority remained weak as most of the field commanders were chosen by the vote of the troops. The common troops were more or less armed civilians, whose military training, discipline and combat morale were both inadequate and low.[61]

Ali Aaltonen was replaced on 28 January 1918 by Eero Haapalainen as commander-in-chief. He, in turn, was displaced by the Bolshevik triumvirate of Eino Rahja, Adolf Taimi and Evert Eloranta on 20 March. The last commander-in-chief of the Red Guard was Kullervo Manner, from 10 April until the last period of the war when the Reds no longer had a named leader. Some talented local commanders, such as Hugo Salmela in the Battle of Tampere, provided successful leadership, but could not change the course of the war. The Reds achieved some local victories as they retreated from southern Finland toward Russia, such as against German troops in the Battle of Syrjäntaka on 28–29 April in Tuulos.[62]

.jpg)

Around 50,000 of the former czar's army troops were stationed in Finland in January 1918. The soldiers were demoralised and war-weary, and the former serfs were thirsty for farmland set free by the revolutions. The majority of the troops returned to Russia by the end of March 1918. In total, 7,000 to 10,000 Red Russian soldiers supported the Finnish Reds, but only around 3,000, in separate, smaller units of 100–1,000 soldiers, could be persuaded to fight in the front line.[63]

The revolutions in Russia divided the Soviet army officers politically and their attitude towards the Finnish Civil War varied. Mikhail Svechnikov led Finnish Red troops in western Finland in February and Konstantin Yeremejev Soviet forces on the Karelian Isthmus, while other officers were mistrustful of their revolutionary peers and instead co-operated with General Mannerheim, in disarming Soviet garrisons in Finland. On 30 January 1918, Mannerheim proclaimed to Russian soldiers in Finland that the White Army did not fight against Russia, but that the objective of the White campaign was to beat the Finnish Reds and the Soviet troops supporting them.[64]

The number of Soviet soldiers active in the civil war declined markedly once Germany attacked Russia on 18 February 1918. The German-Soviet Treaty of Brest-Litovsk of 3 March restricted the Bolsheviks' support for the Finnish Reds to weapons and supplies. The Soviets remained active on the south-eastern front, mainly in the Battle of Rautu on the Karelian Isthmus between February and April 1918, where they defended the approaches to Petrograd.[65]

White Guards and Sweden's role

.jpg)

While the conflict has been called by some, "The War of Amateurs", the White Army had two major advantages over the Red Guards: the professional military leadership of Gustaf Mannerheim and his staff, which included 84 Swedish volunteer officers and former Finnish officers of the czar's army; and 1,450 soldiers of the 1,900-strong, Jäger battalion. The majority of the unit arrived in Vaasa on 25 February 1918.[66] On the battlefield, the Jägers, battle-hardened on the Eastern Front, provided strong leadership that made disciplined combat of the common White troopers possible. The soldiers were similar to those of the Reds, having brief and inadequate training. At the beginning of the war, the White Guards' top leadership had little authority over volunteer White units, which obeyed only their local leaders. At the end of February, the Jägers started a rapid training of six conscript regiments.[66]

The Jäger battalion was politically divided, too. Four-hundred-and-fifty –mostly socialist– Jägers remained stationed in Germany, as it was feared they were likely to side with the Reds. White Guard leaders faced a similar problem when drafting young men to the army in February 1918: 30,000 obvious supporters of the Finnish labour movement never showed up. It was also uncertain whether common troops drafted from the small-sized and poor farms of central and northern Finland had strong enough motivation to fight the Finnish Reds. The Whites' propaganda promoted the idea that they were fighting a defensive war against Bolshevist Russians, and belittled the role of the Red Finns among their enemies.[67] Social divisions appeared both between southern and northern Finland and within rural Finland. The economy and society of the north had modernised more slowly than that of the south. There was a more pronounced conflict between Christianity and socialism in the north, and the ownership of farmland conferred major social status, motivating the farmers to fight against the Reds.[68]

Sweden declared neutrality both during World War I and the Finnish Civil War. General opinion, in particular among the Swedish elite, was divided between supporters of the Allies and the Central powers, Germanism being somewhat more popular. Three war-time priorities determined the pragmatic policy of the Swedish liberal-social democratic government: sound economics, with export of iron-ore and foodstuff to Germany; sustaining the tranquility of Swedish society; and geopolitics. The government accepted the participation of Swedish volunteer officers and soldiers in the Finnish White Army in order to block expansion of revolutionary unrest to Scandinavia.[69]

A 1,000-strong paramilitary Swedish Brigade, led by Hjalmar Frisell, took part in the Battle of Tampere and in the fighting south of the town. In February 1918, the Swedish Navy escorted the German naval squadron transporting Finnish Jägers and German weapons and allowed it to pass through Swedish territorial waters. The Swedish socialists tried to open peace negotiations between the Whites and the Reds. The weakness of Finland offered Sweden a chance to take over the geopolitically vital Finnish Åland Islands, east of Stockholm, but the German army's Finland operation stalled this plan.[70]

German intervention

In March 1918, the German Empire intervened in the Finnish Civil War on the side of the White Army. Finnish activists leaning on Germanism had been seeking German aid in freeing Finland from Soviet hegemony since late 1917, but because of the pressure they were facing at the Western Front, the Germans did not want to jeopardise their armistice and peace negotiations with the Soviet Union. The German stance changed after 10 February when Leon Trotsky, despite the weakness of the Bolsheviks' position, broke off negotiations, hoping revolutions would break out in the German Empire and change everything. On 13 February, the German leadership decided to retaliate and send military detachments to Finland too. As a pretext for aggression, the Germans invited "requests for help" from the western neighbouring countries of Russia. Representatives of White Finland in Berlin duly requested help on 14 February.[71]

The Imperial German Army attacked Russia on 18 February. The offensive led to a rapid collapse of the Soviet forces and to the signing of the first Treaty of Brest-Litovsk by the Bolsheviks on 3 March 1918. Finland, the Baltic countries, Poland and Ukraine were transferred to the German sphere of influence. The Finnish Civil War opened a low-cost access route to Fennoscandia, where the geopolitical status was altered as a British Naval squadron invaded the Soviet harbour of Murmansk by the Arctic Ocean on 9 March 1918. The leader of the German war effort, General Erich Ludendorff, wanted to keep Petrograd under threat of attack via the Vyborg-Narva area and to install a German-led monarchy in Finland.[72]

On 5 March 1918, a German naval squadron landed on the Åland Islands (in mid-February 1918, the islands had been occupied by a Swedish military expedition, which departed from there in May). On 3 April 1918, the 10,000-strong Baltic Sea Division (German: Ostsee-Division), led by General Rüdiger von der Goltz, launched the main attack at Hanko, west of Helsinki. It was followed on 7 April by Colonel Otto von Brandenstein's 3,000-strong Detachment Brandenstein (German: Abteilung-Brandenstein) taking the town of Loviisa east of Helsinki. The larger German formations advanced eastwards from Hanko and took Helsinki on 12–13 April, while Detachment Brandenstein overran the town of Lahti on 19 April. The main German detachment proceeded northwards from Helsinki and took Hyvinkää and Riihimäki on 21–22 April, followed by Hämeenlinna on 26 April. The final blow to the cause of the Finnish Reds was dealt when the Bolsheviks broke off the peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk, leading to the German eastern offensive in February 1918.[73]

Decisive engagements

Battle of Tampere

.jpg)

In February 1918, General Mannerheim deliberated on where to focus the general offensive of the Whites. There were two strategically vital enemy strongholds: Tampere, Finland's major industrial town in the south-west, and Vyborg, Karelia's main city. Although seizing Vyborg offered many advantages, his army's lack of combat skills and the potential for a major counterattack by the Reds in the area or in the south-west made it too risky.[74]

Mannerheim decided to strike first at Tampere. He launched the main assault on 16 March 1918, at Längelmäki 65 km (40 mi) north-east of the town, through the right flank of the Reds' defence. At the same time, the Whites attacked through the north-western frontline Vilppula–Kuru–Kyröskoski–Suodenniemi. Although the Whites were unaccustomed to offensive warfare, some Red Guard units collapsed and retreated in panic under the weight of the offensive, while other Red detachments defended their posts to the last and were able to slow the advance of the White troops. Eventually, the Whites lay siege to Tampere. They cut off the Reds' southward connection at Lempäälä on 24 March and westward ones at Siuro, Nokia, and Ylöjärvi on 25 March.[75]

The Battle for Tampere was fought between 16,000 White and 14,000 Red soldiers. It was Finland's first large-scale urban battle and one of the four most decisive military engagements of the war. The fight for the area of Tampere began on 28 March, on the eve of Easter 1918, later called "Bloody Maundy Thursday", in the Kalevankangas cemetery. The White Army did not achieve a decisive victory in the fierce combat, suffering more than 50 percent losses in some of their units. The Whites had to re-organise their troops and battle plans, managing to raid the town centre in the early hours of 3 April.[76]

After a heavy, concentrated artillery barrage, the White Guards advanced from house to house and street to street, as the Red Guards retreated. In the late evening of 3 April, the Whites reached the eastern banks of the Tammerkoski rapids. The Reds' attempts to break the siege of Tampere from the outside along the Helsinki-Tampere railway failed. The Red Guards lost the western parts of the town between 4 and 5 April. The Tampere City Hall was among the last strongholds of the Reds. The battle ended 6 April 1918 with the surrender of Red forces in the Pyynikki and Pispala sections of Tampere.[76]

The Reds, now on the defensive, showed increased motivation to fight during the battle. General Mannerheim was compelled to deploy some of the best-trained Jäger detachments, initially meant to be conserved for later use in the Vyborg area. The Battle of Tampere was the bloodiest action of the Civil War. The White Army lost 700–900 men, including 50 Jägers, the highest number of deaths the Jäger battalion suffered in a single battle of the 1918 war. The Red Guards lost 1,000–1,500 soldiers, with a further 11,000–12,000 captured. 71 civilians died, mainly due to artillery fire. The eastern parts of the city, consisting mostly of wooden buildings, were completely destroyed.[77]

Battle of Helsinki

After peace talks between Germans and the Finnish Reds were broken off on 11 April 1918, the battle for the capital of Finland began. At 05:00 on 12 April, around 2,000–3,000 German Baltic Sea Division soldiers, led by Colonel Hans von Tschirsky und von Bögendorff, attacked the city from the north-west, supported via the Helsinki-Turku railway. The Germans broke through the area between Munkkiniemi and Pasila, and advanced on the central-western parts of the town. The German naval squadron led by Vice Admiral Hugo Meurer blocked the city harbour, bombarded the southern town area, and landed Seebataillon marines at Katajanokka.[78]

Around 7,000 Finnish Reds defended Helsinki, but their best troops fought on other fronts of the war. The main strongholds of the Red defence were the Workers' Hall, the Helsinki railway station, the Red Headquarters at Smolna, the Senate Palace–Helsinki University area and the former Russian garrisons. By the late evening of 12 April, most of the southern parts and all of the western area of the city had been occupied by the Germans. Local Helsinki White Guards, having hidden in the city during the war, joined the battle as the Germans advanced through the town.[79]

On 13 April, German troops took over the Market Square, the Smolna, the Presidential Palace and the Senate-Ritarihuone area. Toward the end, a German brigade with 2,000–3,000 soldiers, led by Colonel Kondrad Wolf joined the battle. The unit rushed from north to the eastern parts of Helsinki, pushing into the working-class neighborhoods of Hermanni, Kallio and Sörnäinen. German artillery bombarded and destroyed the Workers' Hall and put out the red lantern of the Finnish revolution. The eastern parts of the town surrendered around 14:00 on 13 April, when a white flag was raised in the tower of the Kallio Church. Sporadic fighting lasted until the evening. In total, 60 Germans, 300–400 Reds and 23 White Guard troopers were killed in the battle. Around 7,000 Reds were captured. The German army celebrated the victory with a military parade in the centre of Helsinki on 14 April 1918.[80]

Battle of Lahti

On 19 April 1918, Detachment Brandenstein took over the town of Lahti. The German troops advanced from the east-southeast via Nastola, through the Mustankallio graveyard in Salpausselkä and the Russian garrisons at Hennala. The battle was minor but strategically important as it cut the connection between the western and eastern Red Guards. Local engagements broke out in the town and the surrounding area between 22 April and 1 May 1918 as several thousand western Red Guards and Red civilian refugees tried to push through on their way to Russia. The German troops were able to hold major parts of the town and halt the Red advance. In total, 600 Reds and 80 German soldiers perished, and 30,000 Reds were captured in and around Lahti.[81]

Battle of Vyborg

After the defeat in Tampere, the Red Guards began a slow retreat eastwards. As the German army seized Helsinki, the White Army shifted the military focus to Vyborg area, where 18,500 Whites advanced against 15,000 defending Reds. General Mannerheim's war plan had been revised as a result of the Battle for Tampere, a civilian, industrial town. He aimed to avoid new, complex city combat in Vyborg, an old military fortress. The Jäger detachments tried to tie down and destroy the Red force outside the town. The Whites were able to cut the Reds' connection to Petrograd and weaken the troops on the Karelian Isthmus on 20–26 April, but the decisive blow remained to be dealt in Vyborg. The final attack began on late 27 April with a heavy Jäger artillery barrage. The Reds' defence collapsed gradually, and eventually the Whites conquered Patterinmäki—the Reds' symbolic last stand of the 1918 uprising—in the early hours of 29 April 1918. In total, 400 Whites died, and 500–600 Reds perished and 12,000–15,000 were captured.[82]

Red and White terror

.jpg)

Both Whites and Reds carried out political violence through executions, respectively termed White Terror (Finnish: valkoinen terrori; Swedish: vit terror) and Red Terror (Finnish: punainen terrori; Swedish: röd terror). The threshold of political violence had already been crossed by the Finnish activists during the First Period of Russification. Large-scale terror operations were born and bred in Europe during World War I, the first total war. The February and October Revolutions initiated similar violence in Finland: at first by Russian army troops executing their officers, later between the Finnish Reds and Whites.[83]

The terror consisted of a calculated aspect of general warfare and, on the other hand, the local, personal murders and corresponding acts of revenge. In the former, the commanding staff planned and organised the actions and gave orders to the lower ranks. At least a third of the Red terror and most of the White terror was centrally led. In February 1918, a Desk of Securing Occupied Areas was implemented by the highest-ranking White staff, and the White troops were given Instructions for Wartime Judicature, later called the Shoot on the Spot Declaration. This order authorised field commanders to execute essentially anyone they saw fit. No order by the less-organised, highest Red Guard leadership authorising Red Terror has been found. The paper was "burned" or the command was oral.[84]

The main goals of the terror were to destroy the command structure of the enemy; to clear and secure the areas governed and occupied by armies; and to create shock and fear among the civil population and the enemy soldiers. Additionally, the common troops' paramilitary nature and their lack of combat skills drove them to use political violence as a military weapon. Most of the executions were carried out by cavalry units called Flying Patrols, consisting of 10 to 80 soldiers aged 15 to 20 and led by an experienced, adult leader with absolute authority. The patrols, specialised in search and destroy operations and death squad tactics, were similar to German Sturmbattalions and Russian Assault units organized during World War I. The terror achieved some of its objectives but also gave additional motivation to fight against an enemy perceived to be inhuman and cruel. Both Red and White propaganda made effective use of their opponents' actions, increasing the spiral of revenge.[85]

The Red Guards executed influential Whites, including politicians, major landowners, industrialists, police officers, civil servants and teachers as well as White Guards. Ten priests of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and 90 moderate socialists were killed. The number of executions varied over the war months, peaking in February as the Reds secured power, but March saw low counts because the Reds could not seize new areas outside of the original frontlines. The numbers rose again in April as the Reds aimed to leave Finland. The two major centres for Red Terror were Toijala and Kouvola, where 300–350 Whites were executed between February and April 1918.[87]

The White Guards executed Red Guard and party leaders, Red troops, socialist members of the Finnish Parliament and local Red administrators, and those active in implementing Red Terror. The numbers varied over the months as the Whites conquered southern Finland. Comprehensive White Terror started with their general offensive in March 1918 and increased constantly. It peaked at the end of the war and declined and ceased after the enemy troops had been transferred to prison camps. During the high point of the executions, between the end of April and the beginning of May, 200 Reds were shot per day. White Terror was decisive against Russian soldiers who assisted the Finnish Reds, and several Russian non-socialist civilians were killed in the Vyborg massacre, the aftermath of the Battle of Vyborg.[88]

In total, 1,650 Whites died as a result of Red Terror, while around 10,000 Reds perished by White Terror, which turned into political cleansing. White victims have been recorded exactly, while the number of Red troops executed immediately after battles remains unclear. Together with the harsh prison-camp treatment of the Reds during 1918, the executions inflicted the deepest mental scars on the Finns, regardless of their political allegiance. Some of those who carried out the killings were traumatised, a phenomenon that was later documented.[89]

End

On 8 April 1918, after the defeat in Tampere and the German army intervention, the People's Delegation retreated from Helsinki to Vyborg. The loss of Helsinki pushed them to Petrograd on 25 April. The escape of the leadership embittered many Reds, and thousands of them tried to flee to Russia, but most of the refugees were encircled by White and German troops. In the Lahti area they surrendered on 1–2 May.[90] The long Red caravans included women and children, who experienced a desperate, chaotic escape with severe losses due to White attacks. The scene was described as a "road of tears" for the Reds, but for the Whites, the sight of long, enemy caravans heading east was a victorious moment. The Red Guards' last strongholds between the Kouvola and Kotka area fell by 5 May, after the Battle of Ahvenkoski. The war of 1918 ended on 15 May 1918, when the Whites took over Fort Ino, a Russian coastal artillery base on the Karelian Isthmus, from the Russian troops. White Finland and General Mannerheim celebrated the victory with a large military parade in Helsinki on 16 May 1918.[90]

The Red Guards had been defeated. The initially pacifist Finnish labour movement had lost the Civil War, several military leaders committed suicide and a majority of the Reds were sent to prison camps. The Vaasa Senate returned to Helsinki on 4 May 1918, but the capital was under the control of the German army. White Finland had become a protectorate of the German Empire and General Rüdiger von der Goltz was called "the true Regent of Finland". No armistice or peace negotiations were carried out between the Whites and Reds and an official peace treaty to end the Finnish Civil War was never signed.[91]

Aftermath and impact

Prison camps

The White Army and German troops captured around 80,000 Red prisoners of war (POWs), including 5,000 women, 1,500 children and 8,000 Russians. The largest prison camps were Suomenlinna (an island facing Helsinki), Hämeenlinna, Lahti, Riihimäki, Tammisaari, Tampere and Vyborg. The Senate decided to keep the POWs detained until each individual's role in the Civil War had been investigated. Legislation making provision for a Treason Court (Finnish: valtiorikosoikeus; Swedish: domstolen för statsförbrytelser) was enacted on 29 May 1918. The judicature of the 145 inferior courts led by the Supreme Treason Court (Finnish: valtiorikosylioikeus; Swedish: överdomstolen för statsförbrytelser) did not meet the standards of impartiality, due to the condemnatory atmosphere of White Finland. In total 76,000 cases were examined and 68,000 Reds were convicted, primarily for treason; 39,000 were released on parole while the mean-length of punishment for the rest was two to four years in jail. 555 people were sentenced to death, of whom 113 were executed. The trials revealed that some innocent adults had been imprisoned.[92]

Combined with the severe food shortages caused by the Civil War, mass imprisonment led to high mortality rates in the POW camps, and the catastrophe was compounded by the angry, punitive and uncaring mentality of the victors. Many prisoners felt that they had been abandoned by their own leaders, who had fled to Russia. The physical and mental condition of the POWs declined in May 1918. Many prisoners had been sent to the camps in Tampere and Helsinki in the first half of April and food supplies were disrupted during the Reds' eastward retreat. Consequently, in June 2,900 prisoners starved to death, or died as a result of diseases caused by malnutrition or the Spanish flu: 5,000 in July; 2,200 in August; and 1,000 in September. The mortality rate was highest in the Tammisaari camp at 34 percent, while the rate varied between 5 percent and 20 percent in the others. In total, around 12,500 Finns perished (3,000–4,000 due to the Spanish flu) while detained. The dead were buried in mass graves near the camps. Moreover, 700 severely weakened POWs died soon after release from the camps.[93]

Most POWs were paroled or pardoned by the end of 1918, after a shift in the political situation. There were 6,100 Red prisoners left at the end of the year and 4,000 at the end of 1919. In January 1920, 3,000 POWs were pardoned and civil rights were returned to 40,000 former Reds. In 1927, the Social Democratic Party government led by Väinö Tanner pardoned the last 50 prisoners. The Finnish government paid reparations to 11,600 POWs in 1973. The traumatic hardships of the prison camps increased support for communism in Finland.[94]

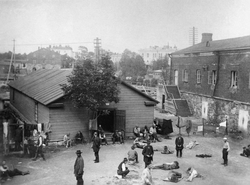

War-torn nation

.jpg)

The Civil War was a catastrophe for Finland: around 36,000 people – 1.2 percent of the population – perished. The war left approximately 15,000 children orphaned. Most of the casualties occurred outside the battlefields: in the prison camps and the terror campaigns. Many Reds fled to Russia at the end of the war and during the period that followed. The fear, bitterness and trauma caused by the war deepened the divisions within Finnish society and many moderate Finns identified themselves as "citizens of two nations."[95]

The conflict caused disintegration within both socialist and non-socialist factions. The rightward shift of power caused a dispute between conservatives and liberals on the best system of government for Finland to adopt: the former demanded monarchy and restricted parliamentarianism; the latter demanded a democratic republic. Both sides justified their views on political and legal grounds. The monarchists leaned on the Swedish regime's 1772 monarchist constitution (accepted by Russia in 1809), belittled the Declaration of Independence of 1917, and proposed a modernised, monarchist constitution for Finland. The republicans argued that the 1772 law lost validity in the February Revolution, that the authority of the Russian czar was assumed by the Finnish Parliament on 15 November 1917, and that the Republic of Finland had been adopted on 6 December that year. The republicans were able to halt the passage of the monarchists' proposal in Parliament. The royalists responded by applying the 1772 law to select a new monarch for the country without reference to Parliament.[96]

The Finnish labour movement was divided into three parts: moderate social democrats in Finland; radical socialists in Finland; and communists in Soviet Russia. The Social Democratic Party had its first official party meeting after the Civil War on 25 December 1918, at which the party proclaimed a commitment to parliamentary means and disavowed Bolshevism and communism. The leaders of Red Finland, who had fled to Russia, established the Communist Party of Finland in Moscow on 29 August 1918. After the power struggle of 1917 and the bloody civil war, the former Fennomans and the social democrats who had supported "ultra-democratic" means in Red Finland declared a commitment to revolutionary Bolshevism–communism and to the dictatorship of the proletariat, under the control of Lenin.[97]

In May 1918, a conservative-monarchist Senate was formed by J. K. Paasikivi, and the Senate asked the German troops to remain in Finland. 3 March 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and 7 March German-Finnish agreements bound White Finland to the German Empire's sphere of influence. General Mannerheim resigned his post on 25 May after disagreements with the Senate about German hegemony over Finland, and about his planned attack on Petrograd to repulse the Bolsheviks and capture Russian Karelia. The Germans opposed these plans due to their peace treaties with Lenin. The Civil War weakened the Finnish Parliament; it became a Rump Parliament that included only three socialist representatives.[98]

On 9 October 1918, under pressure from Germany, the Senate and Parliament elected a German prince, Friedrich Karl, the brother-in-law of German Emperor William II, to become the King of Finland. The German leadership was able to utilise the breakdown of Russia for the geopolitical benefit of the German Empire in Fennoscandia also. The Civil War and the aftermath diminished independence of Finland, compared to the status it had held at the turn of the year 1917–1918.[99]

The economic condition of Finland deteriorated drastically from 1918; recovery to pre-conflict levels was achieved only in 1925. The most acute crisis was in food supply, already deficient in 1917, though large-scale starvation had been avoided that year. The Civil War caused marked starvation in southern Finland. Late in 1918, Finnish politician Rudolf Holsti appealed for relief to Herbert Hoover, the American chairman of the Committee for Relief in Belgium. Hoover arranged for the delivery of food shipments and persuaded the Allies to relax their blockade of the Baltic Sea, which had obstructed food supplies to Finland, and to allow food into the country.[100]

Compromise

On 15 March 1917, the fate of Finns had been decided outside Finland, in Petrograd. On 11 November 1918, the future of the nation was determined in Berlin, as a result of Germany's surrender to end World War I. The German Empire collapsed in the German Revolution of 1918–19, caused by lack of food, war-weariness and defeat in the battles of the Western Front. General Rüdiger von der Goltz and his division left Helsinki on 16 December 1918, and Prince Friedrich Karl, who had not yet been crowned, abandoned his role four days later. Finland's status shifted from a monarchist protectorate of the German Empire to an independent republic. The new system of government was confirmed by the Constitution Act (Finnish: Suomen hallitusmuoto; Swedish: regeringsform för Finland) on 17 July 1919.[101]

The first local elections based on universal suffrage in Finland were held during 17–28 December 1918, and the first free parliamentary election took place after the Civil War on 3 March 1919. The United States and the United Kingdom recognised Finnish sovereignty on 6–7 May 1919. The Western powers demanded the establishment of democratic republics in post-war Europe, to lure the masses away from widespread revolutionary movements. The Finno–Russian Treaty of Tartu was signed on 14 October 1920, with the aim of stabilizing political relations between Finland and Russia and settling the border question.[102]

In April 1918, the leading Finnish social liberal and the eventual first President of Finland, Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg wrote: "It is urgent to get the life and development in this country back on the path that we had already reached in 1906 and which the turmoil of war turned us away from." Moderate social democrat Väinö Voionmaa agonised in 1919: "Those who still trust in the future of this nation must have an exceptionally strong faith. This young independent country has lost almost everything due to the war." Voionmaa was a vital companion for the leader of the reformed Social Democratic Party, Väinö Tanner.[103]

Santeri Alkio supported moderate politics. His party colleague, Kyösti Kallio urged in his Nivala address of 5 May 1918: "We must rebuild a Finnish nation, which is not divided into the Reds and Whites. We have to establish a democratic Finnish republic, where all the Finns can feel that we are true citizens and members of this society." In the end, many of the moderate Finnish conservatives followed the thinking of National Coalition Party member Lauri Ingman, who wrote in early 1918: "A political turn more to the right will not help us now, instead it would strengthen the support of socialism in this country."[104]

Together with other broad-minded Finns, the new partnership constructed a Finnish compromise which eventually delivered a stable and broad parliamentary democracy. The compromise was based both on the defeat of the Reds in the Civil War and the fact that most of the Whites' political goals had not been achieved. After foreign forces left Finland, the militant factions of the Reds and the Whites lost their backing, while the pre-1918 cultural and national integrity and the legacy of Fennomania stood out among the Finns.[105]

The weakness of both Germany and Russia after World War I empowered Finland and made a peaceful, domestic Finnish social and political settlement possible. A reconciliation process led to a slow and painful, but steady, national unification. In the end, the power vacuum and interregnum of 1917–1919 gave way to the Finnish compromise. From 1919 to 1991, the democracy and sovereignty of the Finns withstood challenges from right-wing and left-wing political radicalism, the crisis of World War II and pressure from the Soviet Union during the Cold War.[106]

In popular culture

Between 1918 and the 1950s, mainstream literature and poetry presented the 1918 war from the White victors' point of view, with works such as the "Psalm of the Cannons" (Finnish: Tykkien virsi) by Arvi Järventaus in 1918. In poetry, Bertel Gripenberg, who had volunteered for the White Army, celebrated its cause in "The Great Age" (Swedish: Den stora tiden) in 1928 and V. A. Koskenniemi in "Young Anthony" (Finnish: Nuori Anssi) in 1918. The war tales of the Reds were kept silent.[108]

The first neutrally critical books were written soon after the war, notably, "Devout Misery" (Finnish: Hurskas kurjuus) written by the Nobel Prize laureate Frans Emil Sillanpää in 1919; "Dead Apple Trees" (Finnish: Kuolleet omenapuut) by Joel Lehtonen in 1918; and "Homecoming" (Swedish: Hemkomsten) by Runar Schildt in 1919. These were followed by Jarl Hemmer in 1931 with the book "A Man and His Conscience" (Swedish: En man och hans samvete) and Oiva Paloheimo in 1942 with "Restless Childhood" (Finnish: Levoton lapsuus). Lauri Viita's book "Scrambled Ground" (Finnish: Moreeni) from 1950 presented the life and experiences of a worker family in the Tampere of 1918, including a point of view from outsiders to the Civil War.[109]

Between 1959 and 1962, Väinö Linna described in his trilogy "Under the North Star" (Finnish: Täällä Pohjantähden alla) the Civil War and World War II from the viewpoint of the common people. Part II of Linna's work opened a larger view of these events and included tales of the Reds in the 1918 war. At the same time, a new outlook on the war was opened by Paavo Haavikko's book "Private Matters" (Finnish: Yksityisiä asioita), Veijo Meri's "The Events of 1918" (Finnish: Vuoden 1918 tapahtumat) and Paavo Rintala's "My Grandmother and Mannerheim" (Finnish: Mummoni ja Mannerheim), all published in 1960. In poetry, Viljo Kajava, who had experienced the Battle of Tampere at the age of nine, presented a pacifist view of the Civil War in his "Poems of Tampere" (Finnish: Tampereen runot) in 1966. The same battle is described in the novel "Corpse Bearer" (Finnish: Kylmien kyytimies) by Antti Tuuri from 2007. Jenni Linturi's multilayered "Malmi 1917" (2013) describes contradictory emotions and attitudes in a village drifting towards civil war.[110]

Väinö Linna's trilogy turned the general tide, and after it, several books were written mainly from the Red viewpoint: The Tampere-trilogy by Erkki Lepokorpi in 1977; Juhani Syrjä's "Juho 18" in 1998; "The Command" (Finnish: Käsky) by Leena Lander in 2003; and "Sandra" by Heidi Köngäs in 2017. Kjell Westö's epic novel "Where We Once Went" (Swedish: Där vi en gång gått), published in 2006, deals with the period of 1915–1930 from both the Red and the White sides. Westö's book "Mirage 38" (Swedish: Hägring 38) from 2013, describes post-war traumas of the 1918 war and Finnish mentality in the 1930s. Many of the stories have been utilised in motion pictures and in theatre.[111]

See also

References

Notes

- Finnish: Suomen sisällissota; Swedish: Finska inbördeskriget; Russian: Гражданская война в Финляндии; German: Finnischer Bürgerkrieg. Other designations: Brethren War, Citizen War, Class War, Freedom War, Red Rebellion and Revolution, Tepora & Roselius 2014b, pp. 1–16. According to 1,005 interviews done by the newspaper Aamulehti, the most popular names were as follows: Civil War 29%, Citizen War 25%, Class War 13%, Freedom War 11%, Red Rebellion 5%, Revolution 1%, other name 2% and no answer 14%, Aamulehti 2008, p. 16

Citations

- Including conspirative co-operation between Germany and Russian Bolsheviks 1914–1918, Pipes 1996, pp. 113–149, Lackman 2009, pp. 48–57, McMeekin 2017, pp. 125–136

- Arimo 1991, pp. 19–24, Manninen 1993a, pp. 24–93, Manninen 1993b, pp. 96–177, Upton 1981, pp. 107, 267–273, 377–391, Hoppu 2017, pp. 269–274

- Ylikangas 1993a, pp. 55–63

- Muilu 2010, pp. 87–90

- Paavolainen 1966, Paavolainen 1967, Paavolainen 1971, Upton 1981, pp. 191–200, 453–460, Eerola & Eerola 1998, National Archive of Finland 2004 Archived 10 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Roselius 2004, pp. 165–176, Westerlund & Kalleinen 2004, pp. 267–271, Westerlund 2004a, pp. 53–72, Tikka 2014, pp. 90–118

- Upton 1980, pp. 62–144, Haapala 1995, pp. 11–13, 152–156, Klinge 1997, pp. 483–524, Meinander 2012, pp. 7–47, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50

- Upton 1980, pp. 62–144, Haapala 1995, pp. 11–13, 152–156, Pipes 1996, pp. 113–149, Klinge 1997, pp. 483–524, Lackman 2000, pp. 54–64, Lackman 2009, pp. 48–57, Meinander 2012, pp. 7–47, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50, Hentilä & Hentilä 2016, pp. 15–40

- Upton 1980, pp. 13–15, 30–32, Alapuro 1988, pp. 110–114, 150–196, Haapala 1995, pp. 49–73, Lackman 2000, Jutikkala & Pirinen 2003, p. 397, Jussila 2007, pp. 81–148, 264–282, Meinander 2010, pp. 108–165, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50

- Klinge 1997, pp. 483–524, Jussila, Hentilä & Nevakivi 1999, Lackman 2000, pp. 13–85, Jutikkala & Pirinen 2003, pp. 397, Jussila 2007, pp. 81–150, 264–282, Soikkanen 2008, pp. 45–94, Lackman 2009, pp. 48–57, Ahlbäck 2014, pp. 254–293, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50, Lackman 2014, pp. 216–250

- For centuries, the geographical area of the Finns had been a firm part of Sweden's development to a major Nordic Empire. With the exception of language (the Finnish ground became bilingual), the culture of the people did not differ substantially between the western and eastern part of Sweden, dominated by the Swedish administration and the common Lutheran Church, Alapuro 1988, pp. 29–35, 40–51, Haapala 1995, pp. 49–69, 90–97, Kalela 2008a, pp. 15–30, Kalela 2008b, pp. 31–44, Engman 2009, pp. 9–43, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50

- In contrast to developments in Central Europe and mainland Russia, the policies of the Swedish regime did not result in the economic, political and social authority of the upper-class being based on feudal land property and capital. The peasantry existed in relative freedom, with no tradition of serfdom, and the might of the pre-eminent estates was bound up with an interaction between state formation and industrialisation. Forest industry was a vital sector for Finland and peasants owned a major part of the forest land. These economic considerations gave rise to the birth of Fennomania among a Swedish-speaking upper-class social layer. Alapuro 1988, pp. 19–39, 85–100, Haapala 1995, pp. 40–46, Kalela 2008a, pp. 15–30, Kalela 2008b, pp. 31–44, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50

- Socialism was the antithesis of the class system of the estates. Apunen 1987, pp. 73–133, Haapala 1995, pp. 49–69, 245–250, Klinge 1997, pp. 250–288, 416–449, Kalela 2008a, pp. 15–30, Kalela 2008b, pp. 31–44, Haapala 2014, pp. 21–50