Ukrainian War of Independence

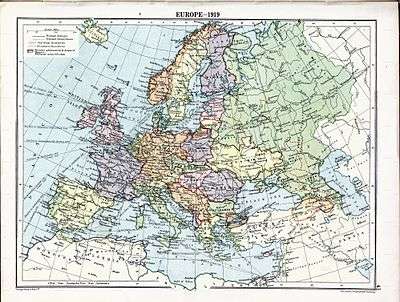

The Ukrainian War of Independence, a period of sustained warlike conflict, lasted from 1917 to 1921 and resulted in the establishment and development of a Ukrainian republic, most of which was later absorbed into the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic of 1922–1991.

| Ukrainian War of Independence | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War I and the Southern Front of the Russian Civil War | ||||||||||

A pro-Tsentralna Rada demonstration in Kiev's Sofia Square, 1917. | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

(1918) (1920–1921) |

(until 1920) |

(from 1920) | ||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Ukraine |

|

|

Early history

|

|

Modern history

|

|

Topics by history |

|

|

The war consisted of a series of military conflicts between different governmental, political and military forces. Belligerents included Ukrainian nationalists, anarchists, Bolsheviks, the forces of Germany and Austria-Hungary, the White Russian Volunteer Army, and Second Polish Republic forces. They struggled for control of Ukraine after the February Revolution (March 1917) in the Russian Empire. The Allied forces of Romania and France also became involved. The struggle lasted from February 1917 to November 1921 and resulted in the division of Ukraine between the Bolshevik Ukrainian SSR, Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia.

The conflict is frequently viewed within the framework of the Southern Front of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922, as well as the closing stage of the Eastern Front of the First World War of 1914–1918.

Background

During the First World War Ukraine was in the front lines of the main combatants: the Entente-allied Russian Empire and Romania, and the Central Powers of the German Empire and Austria-Hungary. By the start of 1917 – after the Brusilov Offensive – the Imperial Russian Army held a front line which partially reclaimed Volhynia and eastern Galicia.

The February Revolution of 1917 encouraged many ethnic groups in the Russian Empire to demand greater autonomy and various degrees of self-determination. A month later, the Ukrainian People's Republic was declared in Kiev as an autonomous entity with close ties to the Russian Provisional Government, and governed by a socialist-dominated Tsentralna Rada ("Central Council"). The weak and ineffective Provisional Government in Petrograd continued its loyalty to the Entente and the increasingly unpopular war, launching the Kerensky Offensive in the summer of 1917. This offensive was a complete disaster for the Imperial Russian Army. The German counter-attack caused Russia to lose all their gains of 1916 and ruined the morale of its army, which caused the near-complete disintegration of the armed forces and the governing apparatus all over the vast Russian Empire.

Many deserting soldiers and officers – particularly ethnic Ukrainians – had lost faith in the future of the Empire, and found the increasingly self-determinant Central Rada a much more favorable alternative. Nestor Makhno began his anarchist activity in the south of Ukraine by disarming deserting Russian soldiers and officers who crossed the Haychur River next to Huliaipole, while in the east in the industrial Donets Basin there were frequent strikes by Bolshevik-infiltrated trade unions.

Ukraine after the Russian revolution

All this led to the October Revolution in Petrograd, which quickly spread all over the empire. The Kiev Uprising in November 1917 led to the defeat of Russian imperial forces in the capital. Soon after, the Central Rada took power in Kiev, while in late December 1917 the Bolsheviks set up a rival Ukrainian republic in the eastern city of Kharkov (Ukrainian: Kharkiv) – initially also called the "Ukrainian People's Republic".[1] Hostilities against the Central Rada government in Kiev began immediately. Under these circumstances, the Rada declared Ukrainian independence on January 22, 1918 and broke ties with Russia.[2][3]

The Rada had a limited armed force at its disposal (the Ukrainian People's Army) and was hard-pressed by the Kharkov government which received men and resources from the Russian Soviet Republic. As a result, the Bolsheviks quickly overran Poltava, Aleksandrovsk (now Zaporizhia), and Yekaterinoslav (now Dnipro) by January 1918. Across Ukraine, local Bolsheviks also formed the Odessa and Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republics; and in the south Nestor Makhno formed the Free Territory – an anarchist region – then allied his forces with the Bolsheviks. Aided by the earlier Kiev Arsenal Uprising, the Red Guards entered the capital on February 9, 1918. This forced the Central Rada to evacuate to Zhytomyr. In the meantime, the Romanians took over Bessarabia. Most remaining Russian Imperial Army units either allied with the Bolsheviks or joined the Ukrainian People's Army. A notable exception was Colonel Mikhail Drozdovsky, who marched his White Volunteer Army unit across the whole of Novorossiya to the River Don, defeating Makhno's forces in the process.

German intervention and Hetmanate, 1918

.png)

(February 1918 article from The New York Times)

.jpg)

Faced with imminent defeat, the Rada turned to its still hostile opponents – the Central Powers – for a truce and alliance, which was accepted by Germany in the first Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (signed on February 9, 1918) in return for desperately needed food supplies which Ukraine would provide to the Germans. The Imperial German and Austro-Hungarian armies then drove the Bolsheviks out of Ukraine, taking Kiev on March 1. Two days later, the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which formally ended hostilities on the Eastern Front of World War I and left Ukraine in a German sphere of influence. The Ukrainian People's Army took control of the Donets Basin in April 1918.[4] Also in April 1918 Crimea was cleared of Bolshevik forces by Ukrainian troops and the Imperial German Army.[5][6] On March 13, 1918 Ukrainian troops and the Austro-Hungarian Army secured Odessa.[5] On April 5, 1918 the German army took control of Yekaterinoslav, and 3 days later Kharkov.[7] By April 1918 all Bolshevik gains in Ukraine were lost; this was due to the apathy of the locals and the then-inferior fighting skills of the Red Army compared to their Austro-Hungarian and German counterparts.[7]

Yet disturbances continued throughout Eastern Ukraine, where local Bolsheviks, peasant self-defense groups known as "green armies", and the anarchist Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine refused to subordinate to Germany. Former Imperial Russian Army General Pavlo Skoropadsky led a successful German-backed coup against the Rada on April 29.[2] He proclaimed the conservative Ukrainian State (also known as the "Hetmanate") with himself as monarch, and reversed many of the socialist policies of the former government. The new government had close ties to Berlin, but Skoropadsky never declared war on any of the Triple Entente powers; Skoropadsky also placed Ukraine in a position that made it a safe haven for many upper- and middle-class people fleeing Bolshevik Russia, and was keen on recruiting many former Russian Army soldiers and officers.

Despite sporadic harassment from Makhno, the territory of the Hetmanate enjoyed relative peace until November 1918; when the Central Powers were defeated on the Western Front, Germany completely withdrew from Ukraine. Skoropadsky left Kiev with the Germans, and the Hetmanate was in turn overthrown by the socialist Directorate.

Resumed hostilities, 1919

Almost immediately after the defeat of Germany, Lenin's government annulled their Brest-Litovsk Treaty – which Leon Trotsky described as "no war no peace" – and invaded Ukraine and other countries of Eastern Europe that were formed under German protection. Simultaneously, the collapse of the Central Powers affected the former Austrian province of Galicia, which was populated by Ukrainians and Poles. The Ukrainians proclaimed a Western Ukrainian People's Republic (WUNR) in Eastern Galicia, which wished to unite with the Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR); while the Poles of Eastern Galicia – who were mainly concentrated in Lwów (Ukrainian: Lviv) – gave their allegiance to the newly formed Second Polish Republic. Both sides became increasingly hostile with each other. On January 22, 1919, the Western Ukrainian People's Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic signed an Act of Union in Kiev. By October 1919, the Ukrainian Galician Army of the WUNR was defeated by Polish forces in the Polish–Ukrainian War and Eastern Galicia was annexed to Poland; the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 granted Eastern Galicia to Poland for 25 years.[8]

The defeat of Germany had also opened the Black Sea to the Allies, and in mid-December 1918 some mixed forces under French command were landed at Odessa and Sevastopol, and months later at Kherson and Nikolayev (Ukrainian: Mykolaiv). The cause and purpose of French intervention was not entirely clear; French military leaders quickly became disillusioned by internal quarrels within the anti-Bolshevik forces that prevented effective collaboration against Bolshevik pressures, and they particularly criticized the White Russian Volunteer Army for its arrogance towards the local population. Strong anti-foreigner feelings among Ukrainians convinced French officers that intervention in this climate of hostility was doomed without massive support. When the French government failed to supply enough equipment and manpower for extensive military operations, the French army faced defeat at the hands of pro-Bolshevik forces and French officers counseled Paris to withdraw the expedition from Odessa and Crimea.

A new, swift Bolshevik offensive overran most of Eastern and central Ukraine in early 1919. Kiev – under the control of Symon Petliura's Directorate – fell to the Red Army again on February 5, and the exiled Soviet Ukrainian government was re-instated as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, moving to Kiev on March 15. The Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR) faced imminent defeat against the Bolsheviks – it was reduced to a strip of land along the Polish border with its capital moving from Vinnytsia to Proskurov (now Khmelnytskyi), then to Kamianets-Podilskyi, and finally to Rivne. But the UNR was saved when the Bolshevik armies had to regroup against a renewed White Russian offensive in South Russia and the Urals, which threatened the very existence of Bolshevism – and so required more urgent attention. During the spring and summer of 1919, Anton Denikin's Volunteer Army and Don Army overran all of central and Eastern Ukraine and made significant gains on other fronts. Yet by winter the tide of war reversed decisively, and by 1920 all of Eastern and central Ukraine except Crimea was again in Bolshevik hands. The Bolsheviks also betrayed and defeated Nestor Makhno, their former ally against Denikin.

Polish involvement, 1920

Again facing imminent defeat, the UNR turned to its former adversary, Poland; and in April 1920, Józef Piłsudski and Symon Petliura signed a military agreement in Warsaw to fight the Bolsheviks.[2] Just like the former alliance with Germany, this move partially sacrificed Ukrainian sovereignty: Petliura recognised the Polish annexation of Galicia and agreed to Ukraine's role in Piłsudski's dream of a Polish-led federation in Eastern Europe.

Immediately after the alliance was signed, Polish forces joined the Ukrainian army in the Kiev Offensive to capture central and southern Ukraine from Bolshevik control. Initially successful, the offensive reached Kiev on May 7, 1920. However, the Polish-Ukrainian campaign was a pyrrhic victory: in late May, the Red Army led by Mikhail Tukhachevsky staged a large counter-offensive south of Zhytomyr which pushed the Polish army almost completely out of Ukraine, except for Lviv in Galicia. In yet another reversal, in August 1920 the Red Army was defeated near Warsaw and forced to retreat. The White forces, now under General Wrangel, took advantage of the situation and started a new offensive in southern Ukraine. Under the combined circumstances of their military defeat in Poland, the renewed White offensive, and disastrous economic conditions throughout the Russian SFSR – these together forced the Bolsheviks to seek a truce with Poland.

End of hostilities, 1921

Soon after the Battle of Warsaw the Bolsheviks sued for peace with the Poles. The Poles, exhausted and constantly pressured by the Western governments and the League of Nations, and with its army controlling the majority of the disputed territories, were willing to negotiate. The Soviets made two offers: one on 21 September and the other on 28 September. The Polish delegation made a counteroffer on 2 October. On the 5th, the Soviets offered amendments to the Polish offer, which Poland accepted. The Preliminary Treaty of Peace and Armistice Conditions between Poland on one side and Soviet Ukraine and Soviet Russia on the other was signed on 12 October, and the armistice went into effect on 18 October.[9][10] Ratifications were exchanged at Liepāja on 2 November 1920. Long negotiations of the final peace treaty ensued.

Meanwhile, Petliura's Ukrainian forces, which now numbered 23,000 soldiers and controlled territories immediately to the east of Poland, planned an offensive in Ukraine for 11 November but were attacked by the Bolsheviks on 10 November. By 21 November, after several battles, they were driven into Polish-controlled territory.[11]

On March 18, 1921, Poland signed a peace treaty in Riga, Latvia with Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine.[2] This effectively ended Poland's alliance obligations with Petliura's Ukrainian People's Republic. According to this treaty, the Bolsheviks recognized Polish control over Galicia (Ukrainian: Halychyna) and western Volhynia – the western part of Ukraine – while Poland recognized the larger central parts of Ukrainian territory, as well as eastern and southern areas, as part of Soviet Ukraine.

Having secured peace on the Western front, the Bolsheviks immediately moved to crush the remnants of the White Movement. After a final offensive on the Isthmus of Perekop, the Red Army overran Crimea. Wrangel evacuated the Volunteer Army to Constantinople in November 1920. After its military and political defeat, the Directorate continued to maintain control over some of its military forces; in October 1921, it launched a series of guerrilla raids into central Ukraine that reached as far east as the modern Kiev Oblast ("Kiev province"). On November 4, the Directorate's guerrillas captured Korosten and seized a cache of military supplies. But on November 17, 1921, this force was surrounded by Bolshevik cavalry and destroyed.

Aftermath

In the current Chyhyryn Raion of Cherkasy Oblast (then in the Kiev Governorate), a local man named Vasyl Chuchupak led the "Kholodnyi Yar Republic" which strived for Ukrainian independence. It lasted from 1919 to 1922, making it the last territory held by armed supporters of an independent Ukrainian state before the incorporation of Ukraine into the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian SSR.[12][13][14]

In 1922, the Russian Civil War was coming to an end in the Far East, and the Communists proclaimed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) as a federation of Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Transcaucasia. The Ukrainian Soviet government was nearly powerless in the face of a centralized monolith Communist Party apparatus based in Moscow. In the new state, Ukrainians initially enjoyed a titular nation position during the nativization and Ukrainization periods. However, by 1928 Joseph Stalin had consolidated power in the Soviet Union. Thus a campaign of cultural repression started, cresting in the 1930s when a massive famine – the Holodomor – struck the republic, claiming several millions of lives. The Polish-controlled part of Ukraine had a different fate: there was very little autonomy, both politically and culturally, but it was not affected by famine. In the late 1930s the internal borders of the Ukrainian SSR were redrawn, yet no significant changes were made.

The political status of Ukraine remained unchanged until the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between the USSR and Nazi Germany in August 1939, in which the Red Army allied with Nazi Germany to invade Poland and incorporate Volhynia and Galicia into the Ukrainian SSR. In June 1941, Germany and its allies invaded the Soviet Union and conquered Ukraine completely within the first year of the conflict. Following the Soviet victory on the Eastern Front of World War II, to which Ukrainians greatly contributed, the region of Carpathian Ruthenia – formerly a part of Hungary before 1919, of Czechoslovakia from 1919 to 1939, of Hungary between 1939 and 1944, and again of Czechoslovakia from 1944 to 1945 – was incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR, as were parts of interwar Poland. The final expansion of Ukraine took place in 1954, when the Crimea was transferred to Ukraine from Russia with the approval of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.

Legacy

The war is portrayed in Mikhail Bulgakov's novel The White Guard.

Many folk songs were written from 1918 to 1922 that were inspired by people and events of this conflict. "Oi u luzi chervona kalyna" and "Oi vydno selo" were inspired by the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen unit of the Austro-Hungarian Army, which became the core battalion of the West Ukrainian People's Republic's Ukrainian Galician Army. "Pisnya pro Tiutiunnyk" was inspired by events surrounding Ukrainian People's Army brigade commander Yuriy Tiutiunnyk. Another song written at this time was "Za Ukrayinu". These "war songs" started to be sung publicly again in the western part of the Ukrainian SSR after the introduction of glasnost (Ukrainian: hlasnist) by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, and regained popularity throughout Ukraine after independence – especially during the current Russian military intervention.

Another musical legacy of this period was the Ukrainian Republic Capella (later the Ukrainian National Chorus), set up in early 1919 by the Directorate government of Symon Petliura. Under the direction of Oleksandr Koshetz, the Capella/Chorus toured Europe and North America from 1919 to 1921 and while in exile from 1922 to 1927; popularising the songs "Shchedryk" and "Oi khodyt son, kolo vikon" – which influenced the composition of the popular English language songs "Carol of the Bells" and "Summertime", respectively.

In the 21st century the Kholodnyi Yar Republic flag was seen during the Euromaidan demonstrations and was later used by the Azov Battalion in the War in Donbas.[14]

Gallery

The coat of arms of the Ukrainian People's Republic (1917–1918); restored under the Directorate (November 1918 – 1921).

The coat of arms of the Ukrainian People's Republic (1917–1918); restored under the Directorate (November 1918 – 1921). The first flag of the Ukrainian People's Republic, used late 1917 to March 1918.

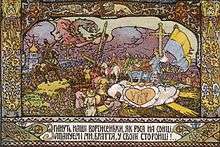

The first flag of the Ukrainian People's Republic, used late 1917 to March 1918. A propaganda leaflet in support of the Ukrainian People's Republic; designed by B. Shippikh in Kiev, 1917.

A propaganda leaflet in support of the Ukrainian People's Republic; designed by B. Shippikh in Kiev, 1917.

.png) The flag of the Ukrainian SSR (the "Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic") in 1919; note the Ukrainian language acronym "УCPP" in the canton.

The flag of the Ukrainian SSR (the "Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic") in 1919; note the Ukrainian language acronym "УCPP" in the canton. The coat of arms of Skoropadsky's Ukrainian State ("Hetmanate"), 1918.

The coat of arms of Skoropadsky's Ukrainian State ("Hetmanate"), 1918. The flag used by Skoropadsky's Ukrainian State in 1918; Petliura's Directorate kept Skoropadsky's flag for their revived Ukrainian People's Republic (November 1918 – 1921).1

The flag used by Skoropadsky's Ukrainian State in 1918; Petliura's Directorate kept Skoropadsky's flag for their revived Ukrainian People's Republic (November 1918 – 1921).1

Notes

1The Verkhovna Rada in 1992 used this design as the basis for the modern Ukrainian national flag.

See also

- Central Council of Ukraine

- Universals (Central Council of Ukraine)

- Ukrainian State

- Pavlo Skoropadsky

- Directorate of Ukraine

- Akt Zluky

- Polish–Ukrainian War

- Ukrainian–Soviet War

- Ukrainian People's Army

- Ukrainian Galician Army

- Ukrainian Air Force

- Ukrainian People's Republic Air Fleet

- Navy of the Ukrainian People's Republic

- Za Ukrayinu

- Finnish Civil War

- Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic

- Odessa Soviet Republic

- Galician Soviet Socialist Republic

References

- Ukrainian (Soviet) People's Republic at WMS Archived 2006-06-23 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- J. Kim Munholland. "Ukraine". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Reid, Anna (2000). Borderland : A Journey Through the History of Ukraine. Westview Press. p. 33. ISBN 0-8133-3792-5.

- (in Ukrainian) 100 years ago Bakhmut and the rest of Donbass liberated, Ukrayinska Pravda (April 18, 2018)

- Tynchenko, Yaros (March 23, 2018), "The Ukrainian Navy and the Crimean Issue in 1917-18", The Ukrainian Week, retrieved October 14, 2018

- Germany Takes Control of Crimea, New York Herald (May 18, 1918)

- War Without Fronts: Atamans and Commissars in Ukraine, 1917-1919 by Mikhail Akulov, Harvard University, August 2013 (page 102 and 103)

- Arkadii Zhukovsky. "Struggle for Independence (1917–1920)". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- (in Polish) Wojna polsko-bolszewicka. Entry at Internetowa encyklopedia PWN. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 4, pp. 8–45.

- Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopedia, Volume I (1963). Edited by Volodymyr Kubiyovych. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 831–833 and pp.872–874

- (in Ukrainian) In honor of the chieftain blessed knives, Gazeta.ua (21 April 2010)

- (in Ukrainian) Gerashchenko offers a National Park "Cold Yar", Ukrinform (19 October 2016)

- "Russian-Ukrainian war never stopped", Gazeta.ua (12 December 2014)

External links

- "Russian Civil War 1918-1820". OnWar.com. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- "31 серпня 1919 року. Як галичани з денікінцями Київ звільняли (August 31, 1919. How Galicians and Denikians liberated Kiev)". Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian).

- J. Kim Munholland. "The French army and intervention in Southern Russia, 1918–1919". Cahiers du monde russe (in French). Editions Ehess. Archived from the original on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- "The beginning of the Civil War and war intervention". RKKA (in Russian). Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Der Vormarsch der Flieger Abteilung 27 in der Ukraine (in German) (The advances of Flight Squadron 27 in the Ukraine). This portfolio, comprising 263 photographs mounted on 48 pages, is a photo-documentary of the German occupation and their military advances through southern Ukraine in the spring and summer of 1918.