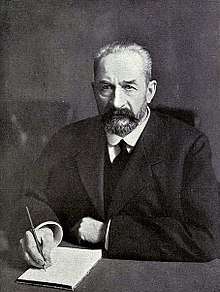

Georgy Lvov

Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov (Russian: Гео́ргий Евге́ньевич Львов; 2 November [O.S. 21 October] 1861 – 7/8 March 1925) was a Russian statesman and the first post-imperial prime minister of Russia, from 15 March to 21 July 1917.

Georgy Lvov Георгий Львов | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister-Chairman of the Russian Provisional Government | |

| In office 15 March 1917 – 21 July 1917 | |

| Monarch | Vacant |

| Preceded by | Nikolai Golitsyn (Prime Minister of Russia), Nicholas II (Emperor of Russia) |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Kerensky |

| Minister of Interior | |

| In office 15 March 1917 – 21 July 1917 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Alexander Protopopov |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Avksentiev |

| 8th Prime Minister of Russia | |

| In office 15 March 1917 – 21 July 1917 | |

| Monarch | Vacant |

| Preceded by | Nikolai Golitsyn |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Kerensky |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov November 2, 1861 Dresden, Kingdom of Saxony, German Confederation |

| Died | March 7, 1925 (age 63) Paris, France |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political party | Constitutional Democratic |

| Alma mater | Moscow State University |

| Profession | Politician |

Pre-Revolution

Prince Lvov was born in Dresden, Germany, and descended from the sovereign Rurik dynasty princes of Yaroslavl. His family moved home to Popovka in the Aleksin district of Tula Governorate from Germany soon after his birth. He graduated from the University of Moscow with a degree in law, then worked in the civil service until 1893. During the Russo-Japanese War he organized relief work in the East and in 1905 joined the liberal Constitutional Democratic Party. A year later he won election to the First Duma, and was nominated for a ministerial position. He became chairman of the All-Russian Union of Zemstvos in 1914, and in 1915 he became a leader of the Union of Zemstvos as well as a member of Zemgor, a joint committee of the Union of Zemstvos and the Union of Towns that hecember 1916, after Prince Lvov's tirades at the Congress of Zemstvos, the Voluntary Organisations would allow no one to work for the government unless thelped supply the military and tend to the wounded from World War I. In Deir collaboration were purchased by political concessions.[1]

He married Countess Julia Alexeievna Bobrinskaya (1867–1903), great-great-granddaughter of Grigory Orlov and Catherine the Great, without issue.

Later years

During the first Russian Revolution and the abdication of Nicholas II, emperor of Russia, Lvov was made head of the provisional government founded by the Duma on 2 March. Unable to rally sufficient support, he resigned in July 1917 in favour of his Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky.

After the October Revolution he settled in Tyumen. In the winter of 1917 he was arrested and transferred to Yekaterinburg. Three months later, Lvov and two other prisoners (Lopukhin and Prince Golitsyn) were released before the court under a written undertaking not to leave the place. The local war commissar, Filipp Goloshchekin, intended to execute Lvov and the other prisoners, but was ordered not to by Isaac Steinberg, the People's Commissar for Justice, a Left-Socialist Revolutionary while they were still in coalition with the Bolsheviks. Lvov immediately left Yekaterinburg, made his way to Omsk, occupied by the anti-Bolshevik Czechoslovak Legion. The Provisional Siberian Government, headed by Pyotr Vologodsky, was formed in Omsk and instructed Lvov to leave for the United States (since it was believed that this country was capable of providing the fastest and most effective assistance to anti-Bolshevik forces) to meet with President Woodrow Wilson and other statesmen to inform them on the aims of the anti-Soviet forces and receiving assistance from former allies of Russia in the First World War. In October 1918 he came to the United States but was late as in November of the same year the First World War ended and preparations began for the peace conference in Paris, where the centre of world politics moved.

Having failed to achieve any practical results in the USA, Lvov returned to France, where in 1918–1920 he was at the head of the Russian political meeting in Paris. He was at the source of the labor exchanges system to help Russian emigrants, transferred to their disposal the funds of Zemgor, stored in the National Bank of the United States. Later he left politics, living in Paris in poverty, working at handicraft and writing his memoirs.

Memorials

There is a memorial to Prince Lvov in Aleksin as well as a small exhibition on him in the town museum. In Popovka there is another memorial opposite his local church and a plaque on the wall of the local school he founded. He died in Boulogne-sur-Seine and is buried in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery in France.

A relative of his by the name of Prince Andre Nikita Lwoff (1901–1933), variously described as either Georgy Lvov's son or nephew, is buried in the old cemetery in Menton.

Further reading

Lvov wrote an autobiography, 'Воспоминания' ("Memories"), while in exile and a biography was also written in 1932 by Tikhon Polner entitled 'Жизненный путь князя Георгія Евгеніевича Львова. Личность. Взгляды. Условія дѣятельности' ("The Life Course of Prince Georgy Yevgenievich Lvov. Personality. Views. Conditions of Activity"). Neither has been translated but both have been reprinted and are still available in Russian.

Notes

Note on transliteration: An older French form, Lvoff, is used on his tombstone. Georgy can be written as Georgi and is sometimes seen in its translated form, George or Jorge.

References

- G. Katkov (1967) Russia 1917. The February Revolution, p. 228.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Georgy Lvov. |

- (in Russian) Lvov Days and memorials

- (in Russian) Aleksin Museum of Art and Regional Studies

- (in Russian) Publishers of Lvov's biographies

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Nikolai Golitsyn (Prime Minister) Nicholas II of Russia (Emperor) |

Minister-Chairman of the Russian Provisional Government 15 March 1917 – 21 July 1917 |

Succeeded by Alexander Kerensky |