Architecture of Finland

The architecture of Finland has a history spanning over 800 years,[1] and while up until the modern era the architecture was strongly influenced by currents from Finland's two respective neighbouring ruling nations Sweden and Russia, from the early 19th century onwards influences came directly from further afield: first when itinerant foreign architects took up positions in the country and then when the Finnish architect profession became established.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Finland |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

|

Mythology and folklore

|

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

|

Art

|

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

Symbols |

|

Furthermore, Finnish architecture in turn has contributed significantly to several styles internationally, such as Jugendstil (or Art Nouveau), Nordic Classicism and Functionalism. In particular, the works of the country's most noted early modernist architect Eliel Saarinen have had significant worldwide influence. Even more renowned than Saarinen has been modernist architect Alvar Aalto, who is regarded as one of the major figures in the world history of modern architecture.[2] In an article from 1922 titled "Motifs from past ages", Aalto discussed national and international influences in Finland, and as he saw it:

Seeing how people in the past were able to be international and unprejudiced and yet remain true to themselves, we may accept impulses from old Italy, from Spain, and from the new America with open eyes. Our Finnish forefathers are still our masters.[3]

In a 2000 review article of twentieth century Finnish architecture, Frédéric Edelmann, arts critic of the French newspaper Le Monde, suggested that Finland has more great architects of the status of Alvar Aalto in proportion to the population than any other country in the world.[4] Finland's most significant architectural achievements are related to modern architecture, mostly because the current building stock has less than 20% that dates back to before 1955, which relates significantly to the reconstruction following World War II and the process of urbanisation which only gathered pace after the war.[5]

1249 is the date normally given for the beginning of Swedish rule over the land now known as Finland (in Finnish, Suomi), and this rule continued until 1809, after which it was ceded to Russia. However, under Russian rule it had a significant degree of autonomy as the Grand Duchy of Finland.[6] Finland declared independence from Russia in 1917, at the time of the Russian Revolution. These historical factors have had a significant bearing on the history of architecture in Finland, along with the founding of towns and the building of castles and fortresses (in the numerous wars between Sweden and Russia fought in Finland), as well as the availability of building materials and craftsmanship and, later on, government policy on issues such as housing and public buildings. As an essentially forested region, timber has been the natural building material, while the hardness of the local stone (predominantly granite) initially made it difficult to work, and the manufacture of brick was rare before the mid-19th century.[7] The use of concrete took on a particular prominence with the rise of the welfare state in the 1960s, in particular in state-sanctioned housing with the dominance of prefabricated concrete elements.[8]

From early architecture to 1809 (including the Swedish colonial period)

The dominance of wood construction

The vernacular architecture of Finland is generally characterised by the predominant use of wooden construction. The oldest known dwelling structure is the so-called kota, a goahti, hut or tent with a covering in fabric, peat, moss, or timber. The building type remained in use throughout Finland until the 19th century, and is still in use among the Sami people in Lapland. The sauna is also a traditional building type in Finland: the oldest known saunas in Finland were made from pits dug into a slope in the ground and primarily used as dwellings in the wintertime. The first Finnish saunas are what nowadays are called "smoke saunas". These differed from modern saunas in that they had no windows and were heated by heating up a pile of rocks (called kiuas) by burning large amounts of wood for about 6–8 hours, and then letting the smoke out through a hatch before entering to enjoy the sauna heat (called löyly).[9]

The tradition of wood construction - beyond the kota hut - has been common throughout the entire northern boreal coniferous zone since prehistoric times.[10] The central structural factor in its success was the corner joining - or "corner-timbering" - technique, whereby logs are laid horizontally in succession and notched at the ends to form tightly secure joints. The origins of the technique are uncertain; though it was used by the Romans in northern Europe in the first century BC, other possible older sources are said to be areas of present-day Russia, but also it is said to have been common among the Indo-Aryan peoples of Eastern Europe, the Near East, Iran and India.[11] Crucial in the development of the "corner-timbering" technique were the necessary tools, primarily an axe rather than a saw.[12] The resulting building type, a rectangular plan, originally comprising a single interior space and with a low-pitched saddle-back roof, is of the same origin as the megaron, the early Greek dwelling house.[10] Its first use in Finland may have been as a storehouse, and later a sauna and then domestic house. The first examples of the "corner-timbering" technique would have used round logs, but a more developed form soon emerged, shaping logs with an axe to a square shape for a surer fit and better insulation. Hewing with an axe was seen as preferable to sawing because the axe-cut surfaces were better in abating water penetration.

According to historians, though the principles of wooden construction may have arrived in Finland from elsewhere, one particular innovation in wooden construction seems to be unique to Finland, the so-called block-pillar church (tukipilarikirkko).[10] Though ostensibly looking like a normal wooden church, the novelty involved the construction of hollow pillars from logs built into the exterior walls, making the walls themselves structurally unnecessary. The pillars are tied internally across the nave by large joists. Usually there were two, but occasionally three pillars on each longitudinal wall. The largest preserved block-pillar church is at Tornio (1686). Other examples are the churches of Vöyri (1627) and Tervola (1687).

In later developments, most particularly in urban contexts, the log frame was then further covered in a layer of wooden planks. It is hypothesised that it was only from the 16th century onwards that wooden houses were painted in the familiar red-ochre or punamulta, containing up to 95% iron oxide, often mixed with tar.[13] The balloon framing technique for timber construction popularized throughout North America only came to Finland in the 20th century. Finnish master builders had travelled to the USA to see how the industrialisation of the timber-framing technique had developed and wrote about it positively in trade journals on their return. Some experiments were made in using the wooden frame, but initially it was not popular.[14] One reason was the thin construction's poor climatic performance (improved in the 1930s with the addition of insulation): also significant was the relatively low price of both timber and labour in Finland. However, by the outbreak of the First World War, the industrialised timber construction system had become more widespread. Also a comparatively recent "import" to Finland is the use of wooden shingles for roofs, dating only from the early 19th century. Previous to that, the traditional system had been a so-called birch-bark roof (in Finnish, malkakatto), comprising a wooden slat base, overlaid with several layers of birch-bark and finished off with a layer of long timber poles by weighed down in places by the occasional boulder. Traditionally, the whole structure was unpainted.[15] The coating of shingles with tar was the modern appropriation of a material first produced in the Nordic countries during the Iron Age, a major export product, especially in sealing wooden boats.

The traditional timber house in Finland was generally of two types: i. Eastern Finland, influenced by Russian traditions. For example, in the Pertinotsa house (now in the Seurasaari Open Air Museum in Helsinki) the family's dwelling rooms are on the upper floors while the animal barns and storerooms are on the ground floor, with hay lofts above them; ii. Western Finland, influenced by Swedish traditions. For example, in the Antti farmstead, originally from the village of Säkylä (nowadays also in Seurasaari), the farmstead consisted of a group of individual log buildings placed around a central farmyard. Traditionally, the first building to be constructed in such a farmstead was the sauna, followed by the first or main room ("tupa") of the main house, where the family would cook, eat and sleep. In summertime they would cook outdoors, and some family members would even choose to sleep in the barns.[16]

The development of wood construction to a more refined level occurred, however, in the construction of churches. The earliest examples were not designed by architects but rather by master builders, who also were responsible for their construction. One of the oldest known wooden church is that of Santamala, in Nousiainen (only archaeological remains existing), dating from the 12th century, with a simple rectangular ground plan of 11,5 x 15 metres.[10] The oldest preserved wooden churches in Finland date back to the 17th century (e.g. Sodankylä old church, Lapland, 1689); none of the medieval churches are remaining as, like all wooden buildings, they were susceptible to fire. Indeed, only 16 wooden churches from the 17th century still exist - though it was not uncommon to demolish a wooden church to make way for a larger stone one.[7]

The designs of the wooden churches were clearly influenced by the church architecture from central and southern Europe as well as Russia, with cruciform plans and Gothic, Romanesque and Renaissance features and detailing. These influences most often, however, came via Sweden. The development of the wooden church in Finland is marked by greater complexity in the plan, the increased size and the refinement of details. The "Lapp church" of Sodankylä (c. 1689), Finland's best-preserved and least changed wooden church, is a simple, unpainted rectangular saddle-back-roofed block, measuring 13 x 8,5 metres with the walls rising to 3,85 metres, and resembling a peasant dwelling. By contrast, Petäjävesi church (planned and built by master builder Jaakko Klemetinpoika Leppänen, 1765) plus the additional sacristy and belfry (Erkki Leppänen, 1821) (a World Heritage Site), though also unpainted on the exterior, has a refined cross plan with even-sized arms, 18 x 18 metres, with a 13-metre-tall interior wooden vault. The atmosphere of the interior of Petäjävesi church is regarded as unique; the large windows, unusual for log construction, give it a soft light.[10]

Even at the time of the building of Petäjävesi church, with its "cross plan", more complex ground plans had already existed in Finland, but in later years the ground plans would become even more complex. The first so-called "double cross plan" in Finland was probably the Ulrika Eleonora church in Hamina (1731, burnt down 1742), built under the direction of master builder Henrik Schultz. It was then replaced by a somewhat similar church, the Church of Elisabet in Hamina (1748–51, destroyed 1821), built under the direction of Arvi Junkkarinen. The double cruciform plan entailed a cross with extensions at the inner corners. This became a model for later churches, for example, Mikkeli church (1754, destroyed 1806) and Lappee church (Juhana Salonen, 1794), the latter incorporating yet a further development, where the transepts of the cross plan are tapered and even chamfered at the corners, as one sees in the plan of the Ruovesi church (1776). Historian Lars Pettersson has suggested that the Katarina Church (1724) in Stockholm, by the French-born architect Jean de la Vallée was the model for the plan of Hamina church and hence the development that followed.[10]

During the Middle Ages there were only 6 towns in Finland (Turku, Porvoo, Naantali, Rauma, Ulvila and Vyborg), with wooden buildings growing organically around a stone church and/or castle. Historian Henrik Lilius has pointed out that Finnish wooden towns were on average destroyed by fire every 30–40 years.[17] They were never rebuilt exactly as they had existed before, and the fire damage offered the opportunity to create new urban structures in accordance with any reigning ideals: for example, completely new grid plans, straightening and widening streets, codes for constructing buildings in stone (in practice often ignored) and the introduction of "fire breaks" in the form of green areas between properties. As a consequence of fires, the greatest part of the wooden towns which have been preserved date from the nineteenth century. For example, the town of Oulu was founded in 1605 by Charles IX beside a medieval castle and, typical for its time, grew organically. In 1651 Claes Claesson drew up a new plan comprising a regular street grid, his proposal outlined on top of the existing "medieval" situation, but still retaining the position of the existing church. Over the following years, there more fires (significantly in 1822 and 1824) and yet more exacting regulations in new town plans regarding wider streets and fire breaks. Of Finland's 6 medieval towns, only Porvoo has retained its medieval town plan.

Tornio block-pillar church, 1686.

Tornio block-pillar church, 1686.- Sodankylä Old Church, Lapland, c.1689.

- Petäjävesi Old Church, "cross plan", 1765, bell tower 1861.

- Petäjävesi Old Church interior.

Elisabet Church, Hamina, "double cross plan", 1748–51, destroyed 1821.

Elisabet Church, Hamina, "double cross plan", 1748–51, destroyed 1821.- Lappee church, 1799.

Lappee church, "double cross plan", 1799.

Lappee church, "double cross plan", 1799. Cathedral and wooden houses of Old Porvoo.

Cathedral and wooden houses of Old Porvoo. Torneå (founded 1620) as depicted in Dahlbergh's Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, 1716.

Torneå (founded 1620) as depicted in Dahlbergh's Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, 1716. View of Turku Cathedral before the Great Fire of 1827.

View of Turku Cathedral before the Great Fire of 1827.

The development of stone construction

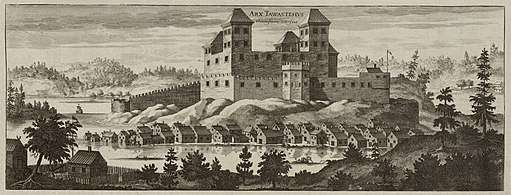

The use of stone construction in Finland was initially limited to the few medieval castles and churches in the country. The construction of castles was part of a project by the Swedish crown to construct both defensive and administrative centres throughout Finland. Six castles of national importance were built during the medieval period, from the second half of the 13th century onwards: Kastelholm on the Åland Islands, Turku, and Raseborg on the south-west coast, Vyborg on an islet off the south-east coast and Häme and Olavinlinna further inland.[18] The northern-most castle, and situated even further inland, Kajaani, dates from the beginning of the 17th century. Kuusisto, on an island of the same name, and Korsholma on the coast also dates from this later period. The earlier parts of the castle constructions are characterised by heavy granite boulder constructions, but with ever more refined details in later periods. Strategically, the two most important castle were that of Turku and Vyborg. The three high-medieval Finnish "castle fiefs" were ruled until the 1360s from the castles of Turku, Hämeenlinna and Vyborg. By the beginning of the 14th century, Turku Castle was one of the largest in northern Europe, with over 40 rooms and by the mid-16th century received further changes to withstand cannon fire. Construction of Vyborg castle started in 1293 by order of Torkel Knutsson, Lord High Constable of Sweden. The documentation for the construction of Olavinlinna is unusually clear: it was founded precisely in 1475 by a Danish-born knight, Erik Axelsson Tott who worked in the service of the Swedish crown and was also governor of Vyborg castle; the castle's strategic significance, along with Vyborg castle, was to protect the eastern border from the Novgorod Republic to the east. According to Axelsson's own account, the castle was built by "16 good foreign master masons" - some of them from Tallinn. The castle is built on an island in the Kyrönsalmi strait that connects the lakes Haukivesi and Pihlajavesi; the design was based on the idea of 3 large towers in a line facing north-west and an encircling wall. The castle's present good state of repair is due to a thorough restoration carried out in the 1960s and 70s. Häme Castle, the oldest parts built in stone, said to originate in the 1260s, was originally built in wood, then rebuilt in stone, but then transformed radically in the 14th century in red brick, unique for Finland, with extra lines of defence also in brick added beyond the central bastion. In the 19th century it was converted into a prison in accordance with a design by architect Carl Ludvig Engel.

The Medieval stone building tradition in Finland is also preserved in 73 stone churches and 9 stone sacristies added to otherwise originally wood churches.[10] Probably the oldest stone church is the Church of St. Olaf in Jomala, Åland Islands, completed in 1260–1280. The stone churches are characterised by their massive walls, and predominantly with a single interior space. Small details, such as windows would sometimes be decorated with redbrick detailing, in particular in the gables (e.g. Sipoo Old Church, 1454).[19] An exception among the churches was Turku Cathedral; it was originally built in wood in the late 13th century, but was considerably expanded in the 14th and 15th centuries, mainly in stone but also using brick. The cathedral was badly damaged during the Great Fire of Turku in 1827, and was rebuilt to a great extent afterwards in brick.

Turku Castle, 13th century, viewed in 1934.

Turku Castle, 13th century, viewed in 1934. Vyborg Castle, 13th century, depicted by Torsten Wilhelm Forstén in 1840.

Vyborg Castle, 13th century, depicted by Torsten Wilhelm Forstén in 1840. Olavinlinna castle dates from 1475.

Olavinlinna castle dates from 1475. Häme Castle featured in Erik Dahlbergh's Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, 1660-1716.

Häme Castle featured in Erik Dahlbergh's Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, 1660-1716. Sipoo Old Church (St. Sigfried's Church), 1454.

Sipoo Old Church (St. Sigfried's Church), 1454. St. Olaf's Church, Tyrvää, c. 1516

St. Olaf's Church, Tyrvää, c. 1516

Already in the mid-16th century there was the odd example of importing refined Renaissance architecture principles to Finland. Duke John of Finland (later King John III of Sweden) (1537–92) built refined Renaissance interiors in the otherwise medieval Turku Castle. However, during the 17th century Sweden became a major political power in Europe, extending its territory into present day Estonia, Russia and Poland - and this expansiveness was reflected in its architecture over the next century. These architectural ambitions were realised in Finland, too, and markedly in the founding of new towns. Four new towns were founded along the Gulf of Bothnia on the west coast of Finland during the reign of Gustavus II Adolphus: Nystad (Uusikaupunki in Finnish) in 1617, and Nykarleby (Uusikaarlepyy in Finnish), Karleby (Kokkola in Finnish) and Torneå (Tornio in Finnish) in 1620. All these are characterised by strict grid street plans, which were filled in with single-storey vernacular-style wooden buildings. Even stricter building and planning regulations came with the appointment of Per Brahe as Governor-General of Finland in 1637 (a position he held intermittently until 1653). Among the new towns founded by Brahe were Hämeenlinna, Savonlinna, Kajaani, Raahe and Kristinestad as well as shifting the position of Helsinki.[7]

The Great Northern War (1700–21) and the occupation of Finland by Russia (known as the Great Wrath, 1713–21) led to vast areas of Sweden's territory being lost to Russia, though Finland itself remained part of Sweden. This led to a rethinking of Sweden's defence policies, including the creation of more fortification works in eastern Finland, but in particular the founding of the fortress town of Fredrikshamn (Hamina), with the first plan by Axel von Löwen in 1723. Von Löwen designed a Baroque octagonal "Ideal City" plan, modelled on similar fortress towns in central Europe - though in terms of shape and street pattern it was similar to Palmanova in Italy. However, following the so-called Hat's War between Sweden and Russia in 1741-43, which Sweden again lost, a large area of eastern Finland was ceded to Russia, including Hamina and the fortified towns of Lappeenranta and Savonlinna. The focus of the country's defences then switched to a small provincial coastal town, Helsinki. However, even during Russia's rule of Hamina, the grandeur of its neoclassical architecture continued to grow; and when the town was "returned" to Finland, as all of Finland became a Grand Duchy of Russia in 1809, the refined architecture was continued further, with several buildings designed by Carl Ludvig Engel designed in the then prevailing neoclassical style.

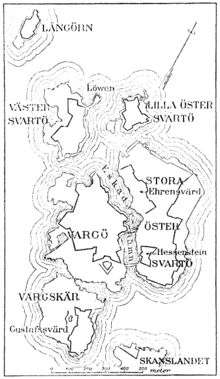

Helsinki had been founded as a trading town by Gustav I in 1550 as the town of Helsingfors, which he intended to be a rival to the Hanseatic city of Reval (today known as Tallinn), directly south across the Gulf of Finland. The siting proved unfavourable and the town remained small and insignificant, and it was plagued by poverty and diseases. The site was changed in 1640. But even with a new grid town plan the architecture of the town remained modest, mainly single-storey buildings. However, the development in Helsinki's architecture came after 1748 with the construction of the Sveaborg fortress - nowadays a World Heritage Site - (first planned by Augustin Ehrensvärd) on a group of islands just off the coast from Helsinki; the heart of the fortress was a dockyard, but distinct Baroque architecture as well as an English-style landscape park were placed within the otherwise unsymmetrical fortification system, all built in stone and brick, and many of the "windows" in the classical facade compositions were in fact painted on. The architecture of the buildings was in a restrained Rococo classicism named after the influential Swedish architect Carl Hårleman(1700-1753). Hårleman had been responsible for completing the Royal Palace in Stockholm, begun by Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, but he himself was also responsible for the design of the grand entrance to the Sveaborg fortress, the so-called King's Gate and may well have had an input, too, in the design of other key residential buildings there.[20]

The height of Sweden's political expansion was marked by the instigation by the crown of the publication Erik Dahlbergh's Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna (Ancient and Modern Sweden), published 1660-1716, containing over 400 carefully prepared engravings illustrating the monuments of the kingdom of Sweden. However, only 9 featured Finland, the towns of Torneå and Vyborg, and a few castles, but mostly coats of arms of the Finnish counties, and depicting them as wilderness areas, or as in the case of the image for "South Finland", a craftsman carving a classical column in a wilderness.[21] By 1721 Sweden's reign as a great power was over, and Russia now dominated the north. The war-weary Swedish parliament, the Riksdag, asserted new powers and reduced the crown to a constitutional monarch, with power held by a civilian government controlled by the Riksdag, albeit by 1772 Gustav III had imposed an absolute monarchy, and by 1788 Sweden and Russia would again be at war in the Russo–Swedish War (1788–1790). But before the war, the so-called new "Age of Freedom" (1719-1772) opened, and the Swedish economy was rebuilt. Advances in the natural sciences put culture in a new perspective; for instance, building techniques improved, the use of the wood-burning cocklestove and glass windows became more common. Also the design of fortifications (often combined with ideas about town planning and architectural design) was at the cutting-edge of warfare technology, with fortifications officers travelling to central Europe to follow new precedents.[7] From 1776 onward, the drawings of all public buildings had to be sent for building approval and review in Stockholm, and new statutes were introduced to prevent fires, so typical for wooden towns. Attempts at achieving a uniformity in architecture was furthered by the introduction of standard "model plans".[22] These were first introduced with the restructuring of the army by Charles XI already in 1682, whereby each of the lands of Sweden were to have 1200 soldiers at disposal, at all times, and two farms were to provide accommodations for one soldier. The "model plans" for military quarters, showing detailed facades and a scale, were designed in a classical Hårleman Rococo style or "Palladian" style, and these in turn affected vernacular architecture, in much the same way as the "model drawings" of the 16th century treatise by Palladio, I quattro libri dell'architettura, influenced the following generations throughout Europe and in the colonies. Among the most influential "pattern books" containing the model drawings were those made up by Swedish fortifications officer Carl Wijnblad (1702-1768), published in 1755, 1756 and 1766, which were spread widely in Finland as well as in Sweden. A particular significant example is the commandant's house in the "castle courtyard" at the heart of the Sveaborg fortress off Helsinki.[20]

Compared to the rest of Europe, the manor houses of Finland are extremely modest in size and architectural refinement.[23] Strictly speaking, a manor house was a gift from the Swedish king, and enjoyed tax privileges. Later manors, stemmed from military officer houses and mansions from privately owned ironworks.[24] The oldest surviving stone manor houses date from the Vasa period in the 16th century; good examples are the manors of Kankainen (founded 1410s) and Vuorentaka (late 1400s), both near Turku. Also in south-west Finland, Louhisaari manor house, completed in 1655 (unknown architect, though probably designed by its builder-owner Herman Klasson Fleming) is a rare example in Finland of a Palladian-style country house.[25] The construction of manor houses in Finland raises the name of an early foreign architect in Finland; Prussian-born Christian Friedrich Schröder (1722-1789) was by training a mason and who worked in Stockholm before moving to Turku in 1756 and was appointed city architect in 1756 - which included responsibility for training assistants. Among his works in Turku, was the rebuilding of the tower of Turku Cathedral[26] Designing in the Rococo and French classical styles, albeit in a more modest idiom, Schröder designed the manor houses of Lapila (1763), Paddais (mid 1760s), Nuhjala (1764), Ala-Lemu (1767), Teijo (1770) and Fagervik (1773), as well as the Rauma town hall (1776).[27]

Kankainen Manor, Henrik Klasson Horn (c. 1550), Augustin Ehrensvärd (c.1756), Claes Aminoff (1935).

Kankainen Manor, Henrik Klasson Horn (c. 1550), Augustin Ehrensvärd (c.1756), Claes Aminoff (1935).- Louhisaari manor house, 1655.

Fredrikshamn (Hamina), fortress-town plan, Axel von Löwen, 1723.

Fredrikshamn (Hamina), fortress-town plan, Axel von Löwen, 1723. Castle courtyard, Sveaborg fortress, Helsinki, after Carl Wijnblad, 1747.

Castle courtyard, Sveaborg fortress, Helsinki, after Carl Wijnblad, 1747. The King's Gate, Sveaborg fortress, Helsinki, Carl Hårleman, 1747.

The King's Gate, Sveaborg fortress, Helsinki, Carl Hårleman, 1747. Rauma Town Hall, Christian Friedrich Schröder, 1776.

Rauma Town Hall, Christian Friedrich Schröder, 1776.- Oravais church, Jacob Rijf, 1792.

Hämeenlinna Church, Louis Jean Desprez, 1799.

Hämeenlinna Church, Louis Jean Desprez, 1799.- Sulkava church, Charles Bassi, 1822.

Grand Duchy period, 1809-1917

Early Grand Duchy period: Neoclassicism and Gothic revival

The cornerstone of Finland as a state was laid in 1809 at the Diet of Porvoo, where Czar Alexander I proclaimed himself constitutional ruler of the new Grand Duchy of Finland and promised to maintain the faith and laws of the land. The creation of a capital was a clear indication of the Czar's will to make the new Grand Duchy a functioning entity. On April 8, 1812 Alexander I declared Helsinki the capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland. At that time Helsinki was only a small wooden town of about 4000 inhabitants, albeit with huge island fortress of Sveaborg and its military garrison nearby.[20] The czar appointed the military engineer Johan Albrecht Ehrenström, a former courtier of Sweden's King Gustavus III, as head of the reconstruction committee, with the task of drawing up a plan for a new stone-built capital. The heart of the scheme was the Senate Square, surrounded by Neoclassical buildings for the state, church and university. In the words of art historian Riitta Nikula, Ehrenström created "the symbolic heart of the Grand Duchy of Finland, where all the main institutions had an exact place dictated by their function in the hierarchy."[7]

In fact, even before the ceding of Finland to Russia in 1809, the advent of Neoclassicism in the mid-18th century arrived with French artist-architect Louis Jean Desprez, who was employed by the Swedish state, and who designed Hämeenlinna church in 1799. Charles (Carlo) Bassi was another foreigner, an Italian-born architect also employed by the Swedish state, who worked especially in the design of churches. Bassi immigrated to Finland and became the first formally skilled architect to settle permanently in Finland.[28] In 1810 Bassi was appointed the first head of the National Board of Building (Rakennushallitus - a government post that remained until 1995), based in Turku, a position he held until 1824. Bassi remained in Finland after power over the country was ceded to Russia. In 1824 his official position as head of the National Board of Building was taken by another immigrant architect, German-born Carl Ludvig Engel.[29]

With the move of the Finnish capital from Turku to Helsinki, Engel had been appointed by Czar Alexander I to design the major new public buildings to be fitted into Ehrenström's town plan: these included the major buildings around the Senate Square; the Senate church, Helsinki University buildings - including Engel's finest interior, Helsinki University Library (1836–45) - and Government buildings. All these buildings were designed following the dominant architectural style of the Russian capital, St. Petersburg, namely Neoclassicism - making Helsinki what was termed a St. Petersburg in miniature, and indeed Ehrenström's plan had even originally included a canal, mimicking a cityscape feature of the former.

In addition to his work in Helsinki, Engel was also appointed "state intendant" with responsibility for the design and supervision of construction of the vast majority of state buildings throughout the country, including tens of church designs, as well as the design and laying out of town plans. Among these works were Helsinki Naval Barracks (1816–38), Helsinki Old Church (1826), Lapua Church (1827), Kärsämäki Church (1828), Pori Town Hall (1831), Hamina Church (1843), Wiurila manor house (1845).[30]

Engel had in his possession a copy of Andrea Palladio's architectural treatise I quattro libri dell'architettura, and Engel scholars have often stressed Engels' indebtedness to Palladian theory. But Engel also kept up correspondence with colleagues from Germany and followed trends there. Engel's relationship with key Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, three years his senior and both having studied at the Bauakademie in Berlin, has yet to be properly verified. The influences from central Europe would also take on board a more formulaic process, typified by standardisations of design formulas in post-revolutionary France by Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, for instance by the use of design grids.[30]

Some of Engel's later works are also characterised by the turn in central Europe to Gothic Revival architecture, with an emphasis on red brick facades typical for central Europe. The German Church (1864) is typical of that period, though designed by another two itinerant architects, the German Harald Julius von Bosse (who had worked much in St. Petersburg) and the Swedish-born Carl Johan von Heideken. In addition to churches, the neo-Gothic style was also dominant for the buildings of the growing industrial manufacturers, including the Verla mill in Jaala (1892) - nowadays a World Heritage Site - designed by Edward Dippel. The emergence of various revivalist styles throughout Europe - in the search for a new "national style" - was also felt in Finland, but would not flourish until the advent of Jugendstil at the end of the century; an argument is even made for the influence in Finland of the neo-Romanesque or Rundbogenstil from Germany, particularly associated with Heinrich Hübsch. For example, certain Rundbogenstil features have been noted in Kerimäki Church (1847) - the world's largest wooden church - designed by Adolf Fredrik Granstedt, but with considerable input from the master builders for the project Axel Tolpo and his son Th. J. Tolpo.[7]

C.L. Engel, Helsinki University Library (1845).

C.L. Engel, Helsinki University Library (1845). C.L. Engel, Helsinki Naval Barracks, (1816–38).

C.L. Engel, Helsinki Naval Barracks, (1816–38). Adolf Fredrik Granstedt, Kerimäki Church (1847).

Adolf Fredrik Granstedt, Kerimäki Church (1847). Harald Julius von Bosse and Carl Johan von Heideken, German Church, Helsinki (1864).

Harald Julius von Bosse and Carl Johan von Heideken, German Church, Helsinki (1864). Edward Dippel, Verla paper mill, Jaala (1893)

Edward Dippel, Verla paper mill, Jaala (1893)

The eclectic mixtures of neo-Gothic, neo-Romanesque, neo-Classical and neo-Renaissance architecture continued even during the beginning of the 20th century, with architects using different styles for different projects or even combining elements in the same work. The Turku Main Library, by Karl August Wrede, completed in 1903, was designed in a Dutch late Renaissance style imitating the House of Nobility of 1660 designed by French architect Simon De la Vallée. Swedish architect Georg Theodor von Chiewitz had a fairly successful career in his home country before arriving in Finland in 1851, fleeing a prison sentence in Sweden following bankruptcy, and soon established a career for himself, being named county architect for Turku and Pori in 1852.[31] Among his varied works, he designed new baroque-style town plans for the towns of Pori (1852), Mariehamn (Åland Islands) (1859) and Uusikaupunki (1856), an English-style romantic landscape park for Seinäjoki (1858), neo-gothic churches for Lovisa (1865) and Uusikaupunki (1864), Rundbogenstil-neo-Gothic Lovisa town hall and the House of Nobility in Helsinki (1862), neo-Renaissance Nya Teatern, Helsinki (1853, burnt down 1863) as well as redbrick factory buildings in Littoinen, Turku, Forssa and Tampere and various rustic villas for private clients. A similar eclecticism was continued most successfully by one of Chiewitz's employees, Theodor Höijer (1843-1910), who went on to establish one of the most commercially successful private architecture firms in Helsinki, designing tens of buildings mostly in Helsinki, schools, libraries and several apartment blocks. One of his most famous works, the redbrick Erottaja fire station, Helsinki (1891) is seen as a mixture of neo-Gothic and neo-Renaissance styles modelled on Giotto's Campanile in Florence and the tower of the medieval Palazzo Vecchio also in Florence.[32]

However, the question of "stylistic revival" in Finland has another important cultural-political aspect, the presence of the Russian Empire through the building of Russian Orthodox churches in the second half of the 19th century - though what is regarded as the initiation of the deliberate politico-cultural policy of the Russification of Finland didn't take place until the reign of Czar Nicholas II, from 1899 onward. Initially, just as in the Russian capital, St. Petersburg, the Russian Orthodox churches were initially designed in the prevailing neoclassical style; however, the latter half of the 19th century also saw the emergence of a Russian Revival architecture and Byzantine Revival architecture - part of the interest in Russia as in Finland and elsewhere in Europe of exploring nationalism - with distinct "onion domes", tented roofs and rich decoration.[33] Several such churches were built in Finland, the vast majority in the eastern half of the country, with notable examples in Tampere, Kuopio, Viinijärvi and Kouvola. An early example, the Suomenlinna church (1854) in the fortress off the coast of Helsinki, was designed by Moscow-based architect Konstantin Thon, the same architect who designed, among other key buildings, the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, the Grand Kremlin Palace and the Kremlin Armoury in Moscow. The presence of the Orthodox church in the heart of Helsinki was made clear by the placement of the Uspenski Cathedral (1868) on a prominent hill overlooking the city; its architect, Aleksey Gornostayev was one of the pioneers of the Russian Revival architecture, credited with the rebirth of traditional tented roof architecture of northern Russia, which is also a prominent feature in the Uspenski Cathedral.

Karl August Wrede, Turku Main Library, 1903.

Karl August Wrede, Turku Main Library, 1903. Georg Theodor von Chiewitz, Nya Teatern, Helsinki (1853).

Georg Theodor von Chiewitz, Nya Teatern, Helsinki (1853). Georg Theodor von Chiewitz, House of Nobility, Helsinki (1862).

Georg Theodor von Chiewitz, House of Nobility, Helsinki (1862). Konstantin Thon, Suomenlinna Church in 1908 (1854).

Konstantin Thon, Suomenlinna Church in 1908 (1854)..jpg) Aleksey Gornostayev, Uspenski Cathedral, Helsinki (1868).

Aleksey Gornostayev, Uspenski Cathedral, Helsinki (1868).

This period also marked the establishment of the first architecture courses in Finland, and in 1879 these began at the Polytechnical Institute in Helsinki, though at first with German or German-educated teachers.[34] Other Finns went abroad for various periods of time to study. In fact, Jacob Rijf (1753-1808) is noted as the first Finn to have studied architecture at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in Stockholm in 1783-84, though he is a rare early exception. He became a notable designer of churches throughout Finland, including Hyrynsalmi church (1786) and Oravais church (1797).[35] One hundred years later it was also still quite rare; e.g. notable revivalist-style architect Karl August Wrede studied architecture in Dresden, and Theodor Höijer at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in Stockholm. Also, Gustaf Nyström studied both architecture and town planning in Vienna in 1878-79. His buildings are typical of the eclecticism of the time, designing in both Gothic Revival style and a so-called neo-Renaissance style of classicism, with heavy ornamentation as well as heavy use of colour in interiors but also occasionally in facades, as for instance with his House of the Estates, Helsinki (1891). The semi-circular Rotonda (1902–07), Gustaf Nyström's design for the extension to C.L. Engel's neoclassical Helsinki University Library (1845), demonstrates both an outwardly stylistic continuity with the original - albeit the pilasters have not classical capitals but reliefs, made by the sculptor Walter Runeberg, personifying the sciences - whilst also employing modern techniques in the Art Nouveau interior: the semicircular 6-storey extension comprises a large light-well surrounded by radially placed bookshelves. Due to the then stringent fire-safety requirements, the extension has a framework of steel and reinforced concrete, with reinforced concrete stairs, an iron construction supporting the large glazed roof and metal windows. After graduating at the Polytechnical Institute, Usko Nyström (no relation) had continued his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1890-91; on returning to Finland he initially designed (from 1895 to 1908 in the partnership Usko Nyström-Petrelius-Penttilä) neo-Renaissance architecture - in particular gaining from the growth area of building speculation in middle-class apartment buildings in Helsinki - whilst also developing a more Jugendstil style inspired by National Romanticism, and politically by the pro-independence Fennoman movement.[36] Usko Nyström's chief work, the Grand Hôtel Cascade, Imatra (1903) (nowadays called Imatran Valtionhotelli), is a key Jugendstil style building; the "wilderness hotel", built next to the impressive Imatra Rapids (the biggest in Finland), was intended mostly for wealthy tourists from the Russian Imperial capital of Saint Petersburg, while its architectural style was inspired by Finnish National Romanticism, whilst taking its inspiration partly from the medieval and neo-Renaissance French châteaux Usko Nyström had seen during his time in France.[37]

Gustaf Nyström, House of the Estates, Helsinki (1891).

Gustaf Nyström, House of the Estates, Helsinki (1891). Gustaf Nyström, Rotonda, Helsinki University Library (1906).

Gustaf Nyström, Rotonda, Helsinki University Library (1906). Theodor Höijer, Erottaja fire station, Helsinki (1891).

Theodor Höijer, Erottaja fire station, Helsinki (1891). Grand Hôtel Cascade, Imatra (1903) (nowadays Imatran Valtionhotelli) Usko Nyström, 1903.

Grand Hôtel Cascade, Imatra (1903) (nowadays Imatran Valtionhotelli) Usko Nyström, 1903.

Late Grand Duchy period: Jugend

At the end of the 19th century Finland continued to enjoy greater independence under Russia as a grand duchy; however, this would change with the coming to power of Czar Nicholas II in 1894, who introduced a greater process of "Russification". The reaction to this among the bourgeois classes was evident, too, in the arts, for instance in the music of Jean Sibelius and the artist Akseli Gallén-Kallela - but also in architecture. The Finnish Architects Club was founded in 1892 within the Swedish-speaking Engineering Society (Tekniska Föreningen). Originally a loose forum for collaboration and discussion, its voluntary basis meant that it operated informally in cafés and restaurants. In this way it resembled many of the writers’ or artists’ clubs of the time and generally fostered a collegial spirit of some solidarity. It quickly helped to establish the architect as an artist responsible for aesthetic decisions. In 1903, as a supplement to the engineering publication, the Club published the first issue of Arkitekten (‘The Architect’ in Swedish, the predominant language still in use at the time among professional classes and certainly architects).[38]

In 1889 the artist Albert Edelfelt depicted the national awakening in a poster showing Mme Paris receiving Finland, a damsel, who alights with a model of St Nicholas' Church (later Helsinki Cathedral) on her hat; the parcels in the boat are all marked EU (i.e. Exposition Universelle). A distinct symbolic importance was given in 1900 to Finland receiving its own pavilion at the Paris World Expo, designed by young architects Herman Gesellius, Armas Lindgren and Eliel Saarinen in the so-called Jugendstil style (or Art Nouveau) then popular in Central Europe. The Finnish pavilion was well received by the European press and critics, albeit usually tying the building closely with Finland's cultural-political circumstances. For example, the German art historian and critic Julius Meier-Graefe wrote of the pavilion: "From the peripheries... we would like to mention the extremely effective Finnish pavilion, with its extremely simple and modern design ... the character of the country and the people and the strong conditioning of its artists for the decorative are reflected in the building in the most pleasant way.".[39]

The Jugendstil style in Finland is characterised by flowing lines and the incorporation of nationalistic-mythyological symbols - especially those taken from the national epic, Kalevala - mostly taken from nature and even medieval architecture, but also contemporary sources elsewhere in Europe and even the USA (e.g. H.H. Richardson and the Shingle Style).[40] The more prominent buildings of this National Romantic style were built in stone, but the discovery in Finland of deposits of soapstone, an easily carved metamorphic rock, overcame the difficulty of using only hard granite; an example of this is the facade of the Pohjola Insurance Building, Helsinki (1901) by Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen. The Jugendstil style became associated in Finland with the fight for national independence. The importance of nationalism also was made evident in the actual surveying of Finnish vernacular buildings: all architecture students at that time - at Finland's then only school of architecture, in Helsinki - became acquainted with the Finnish building heritage by measuring and drawing it. From the 1910s onwards, in addition to large medieval castles and churches also 17th and 18th century wooden churches and neoclassical wooden towns were surveyed - a practice which continues in the Finnish schools of architecture even today. The Jugendstil style was used by Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen in key state buildings such as the National Museum and Helsinki Railway Station. Other architects employing the same style were Lars Sonck and Wivi Lönn, one of the first female architects in Finland.

Finnish Pavilion at Paris Expo 1900.

Finnish Pavilion at Paris Expo 1900. Pohjola Insurance Building, Helsinki, Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen, 1901.

Pohjola Insurance Building, Helsinki, Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen, 1901. Tampere Cathedral, Lars Sonck, 1902-1907.

Tampere Cathedral, Lars Sonck, 1902-1907. National Museum of Finland, Helsinki, Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen, 1916.

National Museum of Finland, Helsinki, Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen, 1916.

Even at the height of the Jugendstil style, there were opponents who criticised the stagnant tastes and mythological approaches whereby Jugendstil was becoming institutionalised. The most well-known opponents were architect-critics Sigurd Frosterus and Gustaf Strengel.[41] Frosterus had worked briefly in the office of Belgian-born architect Henry van de Velde in Weimar in 1903, and at the same time Strengel worked in London at the office of architect Charles Harrison Townsend. Their critique was partly inspired by the results for the 1904 competition to design the Helsinki railway station, won by Eliel Saarinen. In the jury report, the architecture of Frosterus's entry was described as "imported". That same year Frosterus entered the competition for the Vyborg railway station, which Saarinen again won. Frosterus was a strict rationalist who wanted to develop architecture towards scientific ideals, instead of the historical approach of Jugendstil. In Frosterus's own words: "We want an iron and brain style for the railway stations and exhibition buildings; we want an iron and brain style for stores, theatres and concert halls."[42] According to him, an architect had to analyse his tasks of construction in order to be able to logically justify his solutions, and he must take advantage of the possibilities of the latest technology. The particular challenge of his time was reinforced concrete. Frosterus considered that the buildings of a modern metropolis should be "constructivist" in expressing their purpose and technology honestly. He designed a number of private residences, but made his major breakthrough in 1916, gaining second prize in the competition for the Stockmann department store in the heart of Helsinki. He was eventually commissioned to realise the building, which was completed after Finland gained independence, in 1930. It would be misleading to see the Jugendstil style as wholly opposed to classicism; Frosterus's own works combined elements of both. Another key example is the Kalevakangas Cemetery Chapel in Tampere, designed by Wäinö Gustaf Palmqvist and Einar Sjöström; they had won an architectural competition for the project in 1911, and it was completed in 1913. While containing many of the decorative elements familiar from Jugendstil, the overall form borrows from a key classical model, the Pantheon in Rome.

Another point of debate at that time was that of the merits of urbanism. Again, of importance here were opposing views from abroad, namely the picturesque theories of town planning proposed by Viennese city planner Camillo Sitte, as put forward in his influential book City Planning According to Artistic Principles (1889) and the opposing classical-rational urbanism point of view also proposed in Vienna by Otto Wagner, heavily influenced by the Parisian model - under the directorship of Baron Haussmann from 1858 to 1870 - of driving wide boulevards through the old labyrinthine city with the intent of modernising traffic and waste management, as well as enabling the greater social control of the population. This debate came to a head in Finland in the first ever town planning design competition in 1898-1900 for the Töölö district of Helsinki. Three entries were lifted out for recognition; first prize to Gustaf Nyström (together with engineer Herman Norrmén), second prize to Lars Sonck, and third prize to a joint entry by Sonck, Bertil Jung and Valter Thomé. Nyström's scheme represented classicism with wide main streets and imposing public buildings arranged in symmetrical axial compositions, and the other two in the Sittesque style, with the street network adapted to the rocky terrain and with picturesque compositions. A fantastic sketch accompanying Sonck's competition entry gives an indication of the imagery he was aiming for, inspired by his travels in Germany. Historian Pekka Korvenmaa makes the point that leading theme was the creation of the atmosphere of medieval urban environments - and Sonck later designed a similar proposal in 1904 to rearrange the immediate surroundings of St.Michael's Church in Helsinki, with numerous "fantastic" spired buildings.[43] In the Töölö competition, undecided what course of action to take, however, the City Council asked the prize-winners to submit new proposals. When this led to further stalemate Nyström and Sonck were commissioned to work together on the final plan combining Nyström's spacious street network and elements of Sonck's Sittesque details. The final plan (1916) under the direction of Jung, made the scheme more uniform, while the architecture is seen as typical of the Nordic Classicism style. A typical street in the plan is that of Museokatu, with tall lines of buildings in a classical style along a curving street line. A still wider (24 metres) new tree-lined boulevard was that of Helsinginkatu, driven through the working-class district of Kallio, first outlined in 1887 by Sonck, but with further input from Nyström, and completed in around 1923.[44]

But even more ambitious than the town plan for Töölö were Eliel Saarinen's two plans also for Helsinki, the Munkkiniemi-Haaga plan of 1910-15 and the Pro-Helsingfors plan of 1918.[45] The former was for a city development of 170 000, which equalled the entire population of central Helsinki at that time. The scheme was equally inspired by the Parisian axiality of Haussman, the intimate residential squares of Raymond Unwin in the English garden cities and the large-scale apartment blocks of Otto Wagner in Vienna. Only small fragments of the scheme were ever completed. The later scheme, which originated from private land speculation rather than public planning, involved the expansion of central Helsinki - which even included filling in the Töölö Bay in the centre of the city - as well as the planning of smaller satellite communities - what Saarinen termed 'organic decentralization', again inspired by the British garden city principle - around the edge of the city. No aspects of the latter scheme were ever realised.

A major architectural-historical event was the emigration of Eliel Saarinen to the United States in 1923, after he received second prize in the Chicago Tribune Tower competition of 1922. On moving to the United States, Saarinen designed the campus for the Cranbrook Academy of Art (1928) in his same architectural style, while architects in Finland moved on much more quickly into modernism.

Vyborg railway station competition entry, Sigurd Frosterus, 1904.

Vyborg railway station competition entry, Sigurd Frosterus, 1904. Stockmann department store, Helsinki, Sigurd Frosterus, 1916-30.

Stockmann department store, Helsinki, Sigurd Frosterus, 1916-30. Kalevakangas Cemetery Chapel, Tampere, Wäinö Gustaf Palmqvist and Einar Sjöström, 1913.

Kalevakangas Cemetery Chapel, Tampere, Wäinö Gustaf Palmqvist and Einar Sjöström, 1913. Lars Sonck, 1920s-30s urbanism, Museokatu, Töölö, Helsinki.

Lars Sonck, 1920s-30s urbanism, Museokatu, Töölö, Helsinki. Oiva Kallio, Helsinki town plan, 1920s.

Oiva Kallio, Helsinki town plan, 1920s.

Post-independence, 1917-

Nordic classicism and international Functionalism

With Finland's independence achieved in 1917, there was a turn away from the Jugendstil style, which became associated with bourgeois culture. In turn there was a brief return to classicism, so-called Nordic Classicism, influenced to an extent by architect study trips to Italy, but also by key examples from Sweden, in particular the architecture of Gunnar Asplund. Notable Finnish architects from this period include J. S. Sirén and Gunnar Taucher, as well as the early work of Alvar Aalto, Erik Bryggman, Martti Välikangas, Hilding Ekelund and Pauli E. Blomstedt. The most notable large scale building from this period was the Finnish Parliament building (1931) by Sirén. Other key buildings built in this style were the Finnish Language Adult Education Centre in Helsinki (1927) by Taucher (with key assistance from P.E. Blomstedt), Vyborg Art Museum and Drawing School (1930) by Uno Ullberg, "Taidehalli" Art Gallery, Helsinki (1928) and Töölö Church, Helsinki (1930) by Hilding Ekelund, and several buildings by Alvar Aalto, in particular the Workers' Club, Jyväskylä (1925), the South-West Finland Agricultural building, Turku (1928), Muuramäki Church (1929) and the early version of the Vyborg Library (1927–1935) before Aalto greatly modified his design in line with the emerging Functionalist style.

But beyond these public buildings designed in the Nordic Classicism style, this same style was also used in timber constructed workers' housing, most famously in the Puu-Käpylä ("Wooden Käpylä") district of Helsinki (1920–1925) by Martti Välikangas. The around 165 houses of Puu-Käpylä, modelled on farmhouses, were built from traditional square log construction clad in vertical boarding, but the construction technique was rationalised with an on-site "factory" with a partly building element technique. The principle of standardization for housing generally would take off during this time. In 1922 the National Board of Social Welfare (Sosiaalihalitus) commissioned architect Elias Paalanen to design different options of farmhouses, which were then published as a brochure, Pienasuntojen tyyppipiirustuksia (Standard drawings for small houses) republished several times. In 1934 Paalanen was commissioned to design an equivalent urban type-house, and he came up with twelve different options. Alvar Aalto, too, became involved, from 1936, in standard small houses, designing for the Ahlström timber and wood product company, with three types of the so-called AA system: 40 m² (Type A), 50 m² (Type B) and 60 m² (Type C). Though based on traditional farmhouses, there are also clear stylistic elements from Nordic Classicism but also modernism. However, it was with the repercussions of the Second World War that the standard system for house design took on even greater potency, with the advent of the so-called Rintamamiestalo house (literally: War-front soldier's house).[46] These were built throughout the country; a particularly well-preserved example is the district of Karjasilta in Oulu. But this same house type also took on a different role in the aftermath of World War II as part of the Finnish war reparations to the Soviet Union; among the "goods" delivered from Finland to the Soviet Union were over 500 wooden houses based on the standard Rintamamiestalo house, deliveries taking place between 1944 and 1948. A number of these houses ended up being exported from the Soviet Union to various places in Poland, where small "Finnish villages" were established; for example, the district of Szombierki in Bytom, as well as in Katowice and Sosnowiec.[47]

Puu-Käpylä workers' housing area Helsinki, 1920–1925.

Puu-Käpylä workers' housing area Helsinki, 1920–1925. Workers' Club, Jyväskylä, Alvar and Aino Aalto, 1925.

Workers' Club, Jyväskylä, Alvar and Aino Aalto, 1925. Taidehalli Art Gallery, Hilding Ekelund and Jarl Eklund, 1928.

Taidehalli Art Gallery, Hilding Ekelund and Jarl Eklund, 1928. Töölö Church, Helsinki, Hilding Ekelund, 1930.

Töölö Church, Helsinki, Hilding Ekelund, 1930. Liittopankki bank building, Helsinki, Pauli E. Blomstedt, 1929.

Liittopankki bank building, Helsinki, Pauli E. Blomstedt, 1929. Finnish Parliament building, J.S. Sirén, 1931.

Finnish Parliament building, J.S. Sirén, 1931. Rintamamiestalo (war veteran) houses, Karjasilta, Oulu, in 1950.

Rintamamiestalo (war veteran) houses, Karjasilta, Oulu, in 1950.- "Finnish houses" in Sosnowiec, Poland, late 1940s.

Apart from housing design, the period of Nordic Classicism is regarded as being fairly brief, surpassed by the more "continental" style – especially in banks and other office buildings – typified by Frosterus and Pauli E. Blomstedt (e.g. Liittopankki bank building, Helsinki, 1929). In reality, however, a synthesis of elements from various styles emerged. Nevertheless, but by the late 1920s and early 1930s there was already a significant move towards Functionalism, inspired most significantly by French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier, but also from examples closer to hand, again Sweden, such as the Stockholm Exhibition (1930) by Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz. However, at the time, there were certainly architects who attempted to articulate their dissatisfaction with static styles, just as Sigurd Frosterus and Gustaf Strengel had criticised the National Romanticism. Pauli E. Blomstedt, who had certainly designed significant buildings in the Nordic Classicism style, then became a vehement critic, writing sarcastically in a 1928 essay "Architectural Anemia" about Nordic Classicism's sense of "good taste", at a time when he had already endorsed the white Functionalism:

There will soon be no difference between an architect and a fashionable tailor. Dress designers travel each spring to Parisian fashion houses, and we architects will make a trip to Stockholm or Gothenburg every now and then and find there the latest novelties of the season, that is, if they have not already been published in our 'Revue des Modes', Byggmästaren journal or Architekten journal. Window frames, ready-made colonnades and bitter-sweet colours, even complete interiors can find their way to Finland. But we have developed during the last few years, and the facades and the ciytscapes are made so harmonious! That's what many say. ...let us add some circles – called medallions – between the windows on some floors, and to demonstrate sensitive artistry, we find a delicate dangling clothesline of a garland, or a flattened-out meander, or even a gilt star, which is an extremely 'elegant' solution.[48]

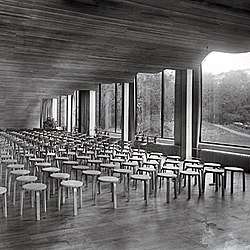

Blomstedt himself died prematurely in 1935, aged 35. The significant vehicle for the development of modernism in Finland was his contemporary, Alvar Aalto, who was a friend of Asplund as well as key Swedish architect Sven Markelius. The latter had invited Aalto to join Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM), ostensibly run by Le Corbusier. Aalto's reputation as a significant contributor to modernism was endorsed by his involvement in CIAM and by the inclusion of his works in significant architectural journals worldwide as well as significant histories of architecture, notably in the second edition (1949) of Space, Time and Architecture by the secretary-general of CIAM, Sigfried Giedion.[49] Aalto's significant buildings from the early period of Modernism, which basically corresponded to the theoretical principles and architectural aesthetic of Le Corbusier and other modernist architects such as Walter Gropius, include the Turku Sanomat newspaper offices, Turku, Paimio tuberculosis sanatorium (1932) (part of a nationwide campaign for tuberculosis sanatorium construction) and Viipuri Library (1927–35). Central to Functionalism was paying close attention to how the building is used. In the case of the Aalto's Paimio tuberculosis sanatorium, the starting point for the design, he himself claimed, was to make the building itself a contributor to the healing process. Aalto liked to call the building a "medical instrument". For instance, particular attention was paid to the design of the patient bedrooms: these generally held two patients, each with his or her own cupboard and washbasin. Aalto designed special non-splash basins, so that the patient would not disturb the other while washing. The patients spent many hours lying down, and thus Aalto placed the lamps in the room out of the patients line of vision and painted the ceiling a relaxing dark green so as to avoid glare. Each patient had their own specially designed cupboard, fixed to the wall and off the floor so as to aid in cleaning beneath it.[50]

Another key Finnish modernist architect from that period, who had also gone through Nordic Classicism, and who was briefly in partnership with Aalto – working together on the design of the Turku Fair of 1929 – was Erik Bryggman, chief among his own works being Resurrection Chapel (1941) in Turku. However, for Giedion the importance of Aalto led in his move away from high modernism, towards an organic architecture – and as Giedion saw it, the impulse for this lay in the natural formations of Finland. Though these "organic elements" were said to be visible already in these first projects, they became more apparent in Aalto's masterpiece house design, Villa Mairea (1937–1939), in Noormarkku – designed for industrialist Harry Gullichsen and his industrialist-heiress wife Maire Gullichsen – the design for which it is felt took inspiration from Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater (1936–1939), in Pennsylvania, USA. Though even when designing a luxury villa, Aalto argued that he felt Villa Mairea would provide research for building standardisation for social housing.[51]

The shift or transition from Nordic Classicism to Functionalism is said sometimes to have been sudden and revolutionary, as with Aalto's Turku Sanomat newspaper offices and Paimio Sanatorium, which employs such distinct modernist features as use of reinforced concrete construction, steel strip windows and flat roofs. The shift in Aalto's design approach from classicism to modernism is epitomised by the Viipuri Library (1927–35), which went through a transformation from an originally classical competition entry proposal (1927) to the completed high-modernist building, following delays in the project, yet still retaining many of the ideals of the original idea. Traces of Nordic Classicism would naturally continue synthesized with Functionalism and a more idiosyncratic individual style, a well-known example being Erik Bryggman's mature work, the Resurrection Chapel in Turku, dating from as late as 1941. Indeed, in a major study of Finnish architecture during this period, albeit with a particular emphasis on Aalto, Greek historian-theoretician Demetri Porphyrios, in Sources of Modern Eclecticism (1983), argues that the "organic" ordering of Aalto's mature works makes use of the same "heterotopic" ordering – i.e. the juxtaposition of contrary elements – that is evident in the Nordic National Romantic architecture from the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century; for example, the works of Eliel Saarinen.[52]

- Viipuri Library, Alvar Aalto, 1927–1935.

Paimio Sanatorium, Alvar Aalto, 1932.

Paimio Sanatorium, Alvar Aalto, 1932. Paimio Sanatorium, patient room ceiling lamp, Alvar Aalto.

Paimio Sanatorium, patient room ceiling lamp, Alvar Aalto..jpg) Alvar Aalto, Villa Mairea, Noormarkku, 1938–1939.

Alvar Aalto, Villa Mairea, Noormarkku, 1938–1939. Resurrection Chapel, Turku, Erik Bryggman, 1941.

Resurrection Chapel, Turku, Erik Bryggman, 1941.

Regional Functionalism

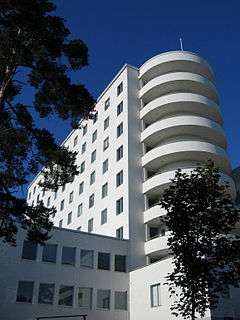

A major event that enabled Finland to display its modernist architecture credentials was the Helsinki Olympic Games. Key among the buildings was the Olympic Stadium by architects Yrjö Lindegren and Toivo Jäntti, the first version of which was the result of an architectural competition in 1938, intended for the games due to be held in 1940 (cancelled due to the war), but eventually held in an enlarged stadium in 1952. The importance of the Olympic Games for architecture was that it coupled the modern, white Functionalist architecture with modernisation of the nation, giving it public endorsement; indeed the general public could contribute to the funding of the stadium's construction by purchasing various souvenir trinkets.[53] Other channels by which Functionalist architecture developed was by means of various state architecture offices, such as the military, industry, and to a small extent tourism. A strong "white Functionalism" characterised the mature architecture of Erkki Huttunen, head of the building department of the retail cooperative Suomen Osuuskauppojen Keskuskunta (SOK), as evident in their production works, warehouses, offices and even shops built throughout the country; the first of these was a combined office and warehouse in Rauma (1931), with white-rendered walls, roof terrace with "ship railing" balustrade, large street-level windows and curved access stairs.[54] The Ministry of Defence had its own building-architecture department, and during the 1930s many of the military's buildings were designed in the "white Functionalism" style. Two examples were the Viipuri military hospital and Tilkka military hospital in Helsinki (1936), both designed by Olavi Sortta.[55] Following independence there was a growing tourism industry with an emphasis on experiencing the wilderness of Lapland: the fashionable white Functionalist architecture of the Hotel Pohjanhovi in Rovaniemi by Pauli E. Blomstedt (1936, destroyed in the Lapland War in 1944) catered to the growing middle-class Finnish tourists as well as foreign tourists to Lapland, though at the same time more modest hostels designed in a vernacular rustic style were also being built.[9]

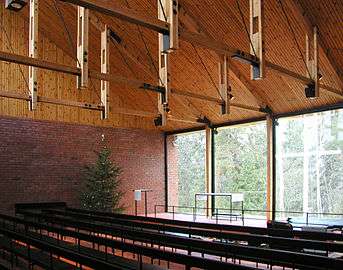

Following World War II, Finland ceded 11% of its territory and 30% of its economic assets to the Soviet Union as part of the Moscow Peace Treaty of 1940. Also 12% of Finland's population, including some 422,000 Karelians, were evacuated. The state response to this has become known as the period of reconstruction. Reconstruction started in the rural areas because still at that time two-thirds of the population lived there.[56] But reconstruction involved not only the repair of war damage (e.g., the destruction of the city of Rovaniemi by the retreating German army) but also the beginnings of greater urbanisation, programmes for standardised housing, building programmes for schools, hospitals, universities and other public service buildings, as well as the construction of new industries and power stations.[57] For instance, architect Aarne Ervi was responsible for the design of five power stations along the Oulujoki river in the decade after the war, and Alvar Aalto designed several industrial complexes following the war, though in fact he had been heavily involved in designing projects of various sizes for Finnish industrial enterprises already since the 1930s.[58] However, for all the expansion of public works, the decade following the war was marred by shortages in building materials, except for wood. The Finnish Lutheran Church also became a key figure in architecture in the interim and post-war period by arranging with the Finnish Association of Architects (SAFA) architectural competitions for the design of new churches and cemeteries/cemetery chapels throughout the country, and significant war-time and post-war examples include: Turku Resurrection Chapel (Erik Bryggman, 1941), Lahti Church (Alvar Aalto, 1950), Vuoksenniska Church (Alvar Aalto, 1952–1957), Vatiala Cemetery Chapel, Tampere (Viljo Rewell, 1960), Hyvinkää Church (Aarno Ruusuvuori, 1960), and Holy Cross Chapel, Turku (Pekka Pitkänen, 1967). Bryggman in particular designed several cemetery chapels but also was the most prolific designer of war graves, designed in conjunction with artists.

Hotel Pohjanhovi, Rovaniemi, Pauli E. Blomstedt, 1936 (destroyed 1944).

Hotel Pohjanhovi, Rovaniemi, Pauli E. Blomstedt, 1936 (destroyed 1944). Tilkka military hospital, Helsinki, Olavi Sortta, 1936.

Tilkka military hospital, Helsinki, Olavi Sortta, 1936. Helsinki Olympic Stadium, Lindegren and Jäntti, 1938–1950.

Helsinki Olympic Stadium, Lindegren and Jäntti, 1938–1950.- SOK offices and warehouse, Oulu, Erkki Huttunen, 1938.

- Pyhakoski Power Station, Aarne Ervi, 1942–1951.

High rise blocks, Tapiola, Viljo Revell, 1953.

High rise blocks, Tapiola, Viljo Revell, 1953. Otaniemi Chapel, Espoo, Kaija Siren (with Heikki Siren), 1954–1957.

Otaniemi Chapel, Espoo, Kaija Siren (with Heikki Siren), 1954–1957. "Serpentine House" housing block, Helsinki, Yrjö Lindegren, 1949–1951.

"Serpentine House" housing block, Helsinki, Yrjö Lindegren, 1949–1951. Roihuvuori housing area, Helsinki, Hilding Ekelund, 1957.

Roihuvuori housing area, Helsinki, Hilding Ekelund, 1957.- Finnish Church, London, Cyril Mardall-Sjöström, 1958.

The 1950s also marked the beginning not only of greater population migration to the cities but also state financed projects for social housing. A key early example is the so-called "Käärmetalo" (literally "Snake house", though usually referred to in English as the "Serpentine house"), (1949–1951) by Yrjö Lindegren; built using traditional building techniques, plastered brick, the building nevertheless has a modern snake-like form that follows the topography of the area whilst also creating small pocket-like yards for the residents.[59] But beyond the matter of form, was the production of mass housing based on systems of standardisation and prefabricated element construction. A leader in the design of social housing was Hilding Ekelund – who had previously been responsible for the design of the athletes' village for the Olympic Games.[60] A challenge to the traditional urbanisation process came, however, with the design of "forest towns", high-rise developments set in forested areas on the outskirts of the major cities, such as the Pihlajamäki suburb of Helsinki (1959–1965), based on a town plan by Olli Kivinen, and building designs by Lauri Silvennoinen, the area comprising white Functionalist-style 9-storey tower blocks and up to 250-metre-long 4–5-storey "lamella" blocks dispersed within a forest setting.[61] Pihlajamäki was also one of the first precast concrete construction projects in Finland. The major example of the goal to set living within nature was Tapiola garden city, located in Espoo, promoted by its founder Heikki von Hertzen to encourage social mobility. The town planning for the garden city was made by Otto-Iivari Meurman, and with the key buildings of the town centre by Aarne Ervi, and other buildings by, among others, Aulis Blomstedt and Viljo Revell.[62] In the 1950s and 1960s, as the Finnish economy began to prosper with greater industrialisation, the state began to consolidate a welfare state, building more hospitals, schools, universities and sports facilities (athletics being a sport Finland had proved successful in internationally). Also larger businesses would have architectural policies, notably the dairy company Valio, in constructing rational high-tech factories and later, their headquarters (Helsinki, 1975–1978) by their own architect Matti K. Mäkinen, together with architect Kaarina Löfström. There was, however, a flip side to the urbanization and the expressed concern for the value of nature; traditional towns, even the old medieval ones, such as Porvoo and Rauma, were under threat of being demolished, to be replaced by straightened streets and large urban developments of prefabricated multi-storey blocks. This did indeed happen to an extent in the cities of Turku – where the wholsale redevelopment was described as the "Turku Disease" –, Helsinki and Tampere; however the latter two did not have medieval architecture at all and even Turku had lost the majority of its medieval building entities at the great fire in 1827. Anyway, the "old town" areas of Porvoo and Rauma were saved, the wooden old town of Rauma, Old Rauma, eventually becoming a UNESCO World Heritage site.[63]

There was also at this time more disposable income; one outlet for this was the growth in the number of leisure homes – previously the preserve of the very wealthy – preferably placed alone on one of the numerous isolated lakesides or the coastal waterfront. An essential part of the leisure home (occupied for summer holidays and intermittently during the spring and autumn, but close up for the winter) has been the sauna, usually as a separate building. Indeed, the sauna had traditionally been a rural phenomenon, and its popularity in modern homes was a consequence of its growth as a leisure-time activity rather than as a washing facility. The Finnish Association of Architects (SAFA) and commercial companies organised design competitions for standardised models of leisure homes and saunas, preferably built in wood. Architects could also use the summer house type and sauna as an opportunity to experiment, an opportunity that many architects still use today. In terms of size and opulence, Aalto's own summer house, the so-called Experimental House, in Muuratsalo (1952–1953) fell between the traditions of middle-class splendor and modest rusticity, while its accompanying lakeside sauna, built from round logs, was a modern application of rustic construction.[64] The 1960s witnessed more experimental summer house types, designed with the objective of serial production. The most noted of these was Matti Suuronen's Futuro House (1968) and Venturo House (1971), of which several were made and sold worldwide. Their success was short lived, however, as production was hit by the 1970s energy crisis.[9]

"Turku Disease": radical change in the townscape, early 1960s.

"Turku Disease": radical change in the townscape, early 1960s. Muuratsalo sauna, Alvar Aalto, c. 1952.

Muuratsalo sauna, Alvar Aalto, c. 1952.- Futuro House (1968), Matti Suuronen.

The late 1950s and 1960s also witnessed a reaction to the then still dominant position of Alvar Aalto in Finnish architecture, though some, most significantly Heikki and Kaija Siren (e.g., Otaniemi Chapel, 1956–1957), Keijo Petäjä (e.g., Lauttasaari Church, Helsinki, 1958), Viljo Revell (e.g., Toronto City Hall, Canada, 1958–1965), Timo Penttilä (e.g., Helsinki City Theatre, 1967), Marjatta and Martti Jaatinen (e.g., Kannelmäki church, 1962–68), and brothers Timo and Tuomo Suomalainen (e.g., Temppeliaukio Church, Helsinki, 1961–1969) developed their own interpretation of a non-rationalist modernist architecture. Taking architecture in an even more idiosyncratic organic line than Aalto was Reima Pietilä, while at the other end of the spectrum was a rationalist line epitomized in the works of Aarne Ervi, Aulis Blomstedt, Aarno Ruusuvuori, Kirmo Mikkola, Kristian Gullichsen, Matti K. Mäkinen, Pekka Salminen, Juhani Pallasmaa and, slightly later, Helin & Siitonen Architects.

Extension to Adult Education Centre, Helsinki (Taucher, 1927) (1959), Aulis Blomstedt

Extension to Adult Education Centre, Helsinki (Taucher, 1927) (1959), Aulis Blomstedt Holy Cross Chapel, Turku (1967), Pekka Pitkänen.

Holy Cross Chapel, Turku (1967), Pekka Pitkänen. Helsinki City Theatre (1967), Timo Penttilä.

Helsinki City Theatre (1967), Timo Penttilä. Tapiola church, Espoo (1965), Aarno Ruusuvuori.

Tapiola church, Espoo (1965), Aarno Ruusuvuori.- Weilin & Göös Print Works, Espoo (1964–1966), Aarno Ruusuvuori.

Dipoli student building, Espoo (1961–1966), Reima and Raili Pietilä.

Dipoli student building, Espoo (1961–1966), Reima and Raili Pietilä. 'Metso' Tampere City Library (1978–1986), Reima and Raili Pietilä.

'Metso' Tampere City Library (1978–1986), Reima and Raili Pietilä.- Järvenpää Church (1968), Erkki Elomaa.

Kortepohja prefabricated housing (1964–1969), Bengt Lundsten and Esko Kahri.

Kortepohja prefabricated housing (1964–1969), Bengt Lundsten and Esko Kahri.%2C_Finland%2C_architect_Kosti_Kuronen.jpg) STS Bank, Tampere (1973), Kosti Kuronen.

STS Bank, Tampere (1973), Kosti Kuronen.