French Army in World War I

This article is about the French Army in World War I. During World War I, France was one of the Triple Entente powers allied against the Central Powers. Although fighting occurred worldwide, the bulk of the fighting in Europe occurred in Belgium, Luxembourg, France and Alsace-Lorraine along what came to be known as the Western Front, which consisted mainly of trench warfare. Specific operational, tactical, and strategic decisions by the high command on both sides of the conflict led to shifts in organizational capacity, as the French Army tried to respond to day-to-day fighting and long-term strategic and operational agendas. In particular, many problems caused the French high command to re-evaluate standard procedures, revise its command structures, re-equip the army, and to develop different tactical approaches.

Background

.jpg)

France had been the major power in Europe for most of the Early Modern Era: Louis XIV, in the seventeenth century, and Napoleon I in the nineteenth, had extended French power over most of Europe through skillful diplomacy and military prowess. The Treaty of Vienna in 1815 confirmed France as a European power broker. By the early 1850s, Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck started a system of alliances designed to assert Prussian dominance over Central Europe. Bismarck's diplomatic maneuvering, and France's maladroit response to such crises as the Ems Dispatch and the Hohenzollern Candidature led to the French declaration of war in 1870. France's subsequent defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, including the loss of its army and the capture of its emperor at Sedan, the loss of territory, including Alsace-Lorraine, and the payment of heavy indemnities, left the French seething and placed the reacquisition of lost territory as a primary goal at the end of the 19th century; the defeat also ended French preeminence in Europe. Following German Unification, Bismarck attempted to isolate France diplomatically by befriending Austria–Hungary, Russia, Britain, and Italy.

After 1870, the European powers began gaining settlements in Africa, with colonialism on that continent hitting its peak between 1895 and 1905. However, colonial disputes were only a minor cause of World War I, as most had been settled by 1914. Economic rivalry was not only a source for some of the colonial conflicts but also a minor cause for the start of World War I. For France, the rivalry was mostly with the rapidly industrializing Germany, which had seized the coal-rich region of Alsace-Lorraine in 1870, and later struggled with France over mineral-rich Morocco.

Another cause of World War I was growing militarism which led to an arms race between the powers. As a result of the arms race, all European powers were ready for war and had time tables that would send millions of reserves into combat in a matter of days.

France was bound by treaty to defend Russia.[1] Austria–Hungary had declared war on Serbia due to the Black Hand's assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, which acted as the immediate cause of the war.[1] France was brought into the war by a German declaration of war on August 3, 1914.[1]

The Pre-War Army and mobilization

.jpg)

In common with most other continental European powers, the French Army was organized on the basis of universal conscription. Each year, the "class" of men turning twenty-one in the upcoming year would be inducted into the French Army and spend three years in active service. After leaving active service they would progress through various stages of reserves, each of which involved a lower degree of commitment.

- Active Army (20–23)

- Reserve of the Active Army (24–34)

- Territorial Army (35–41)

- Reserve of the Territorial Army (42–48)

The peacetime army consisted of 173 infantry regiments, 89 cavalry regiments, and 87 artillery regiments. All were substantially under strength and would be filled out on mobilization by the first three classes of the Reserve (that is, men between 24 and 26). Each regiment would also leave behind a cadre of training personnel to conduct refresher courses for the older reservists, who were organized into 201 Reserve Regiments and 145 Territorial Regiments. Above the regimental level, France was divided into 22 Military Regions, each of which would become an Army Corps on mobilization.

At the apex of the French Army was the General Staff, since 1911 under the leadership of General Joseph Joffre. The General Staff was responsible for drawing up the plan for mobilization, known as Plan XVII. Using the railroad network, the Army would be shifted from their peacetime garrisons throughout France to the eastern border with Germany.

The order for mobilization was given on 1 August 1914, the same day that Germany declared war on Russia. Immediately called to their regiments were the classes of 1896 to 1910, comprising almost three million reservists of 24 to 38 years old.[2]

Organization during the war

.jpg)

Upon mobilization, Joffre became Commander-in-Chief of the French Army. Most of his forces were concentrated in the north east of France, both to attack Alsace-Lorraine and to meet the expected German offensive through the Low Countries.

- First Army (7th, 8th, 13th, 14th, and 21st Army Corps), with the objective of capturing Mulhouse and Sarrebourg.

- Second Army (9th, 15th, 16th, 18th and 20th Army Corps), with the objective of capturing Morhange.

- Third Army (4th, 5th and 6th Army Corps), defending the region around Metz.

- Fourth Army (12th, 17th and Colonial Army Corps) held in reserve around the Forest of Argonne

- Fifth Army (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 10th and 11th Army Corps), defending the Ardennes.

Over the course of the First World War another five field armies would be raised. The war scare led to another 2.9 million men being mobilized in the summer of 1914 and the costly battles on the Western Front forced France to conscript men up to the age of 45. This was done by the mobilization in 1914 of the Territorial Army and its reserves; comprising men who had completed their peacetime service with the active and reserve armies (ages 20–34).[3]

In June 1915, the Allied countries met in the first inter-Allied conference.[4] Britain, France, Belgium, Italy, Serbia and Russia agreed to coordinate their attacks but the attempts were frustrated by German offensives on the Eastern Front and spoiling offensives at Ypres and in the hills west of Verdun.[4]

By 1918, towards the end of the war, the composition and structure of the French army had changed. Forty percent of all French soldiers on the Western Front were operating artillery and 850,000 French troops were infantry in 1918, compared to 1.5 million in 1915. Causes for the drop in infantry include increased machine gun, armored car and tank usage, as well as the increasing significance of the French air force, the Service Aéronautique. At the end of the war on November 11, 1918, the French had called up 8,817,000 men, including 900,000 colonial troops. The French army suffered around 6 million casualties, including 1.4 million dead and 4.2 million wounded, roughly 71% of those who fought.

Commanders in Chief

Joseph Joffre was Commander-in-Chief, a position for which he had been designated since 1911.[5] While serving in this position, Joffre was responsible for development of the Plan XVII the mobilisation and concentration plan for the offensive strategy against Germany, which proved a costly failure.[5] Joffre was thought to be the 'Savior of France' due to his serenity and a refusal to admit defeat, valuable at the beginning of the war, along with his regrouping of retreating Allied forces at the Battle of the Marne.[5] Joffre was effectively relieved of his duties on December 13, 1916, following the heavy human losses at the Battle of Verdun and the Somme, and the defeat of Romania, which appeared for a time to put the Salonika Bridgehead in jeopardy. Due to his popularity, it was not presented to the public as a dismissal when he was promoted to Marshal of France on the same day.[5]

Robert Nivelle, who began the war as a regimental colonel, was appointed Commander-in-Chief.[6] However, after the failure of the Nivelle Offensive in April 1917 he was removed from his position and appointed Commander-in-Chief in North Africa.[6]

On May 15, 1917, Philippe Pétain was made Commander-in-Chief after a few weeks as Army Chief of Staff. The French Army Mutinies had begun during that period, and he restored the fighting capability of the French troops by improving front line living conditions, and conducting only limited offensives.[7] In the Third Battle of the Aisne, fought in May 1918, French positions collapsed due to the local commander General Duchene's defiance of Pétain's recommendation of defence in depth, and Petain's pessimism saw him subordinated to the Supreme Allied Commander Ferdinand Foch.[7]

Western Front

Germany marched through neutral Belgium as part of the Schlieffen Plan to invade France, and by August 23 had reached the French border town of Maubeuge, whose true significance lay within its forts.[8] Maubeuge was a major railway junction and was consequently a protected city.[8] It had 15 forts and gun batteries, totaling 435 guns, along with a permanent garrison of 35,000 troops, a number enhanced by the British Expeditionary Force.[8] The BEF and the French Fifth Army retreated on August 23, and the town was besieged by German heavy artillery starting on August 25.[8] The fortress was surrendered on September 7 by General Fournier, who was later court-martialed, but exonerated, for the capitulation.[8]

The Battle of Guise, launched on August 29, was an attempt by the Fifth Army to capture Guise, they succeeded, but later withdrew on August 30.[9] This delayed the German Second Army's invasion of France, but also hurt Lanrezac's already damaged reputation.[9] The First Battle of the Marne was fought between September 6 and September 12. It started when retreating French forces (the Fifth and Sixth armies), stopped south of the Marne River.[10] Victory seemed close, the First German Army was given orders to surround Paris, unaware the French government had already fled to Bordeaux.[10] The First Battle of the Marne was a French victory, but was a bloody one: the French suffered 250,000 casualties, of which 80,000 died, with similar numbers believed for the Germans, and over 12,700 for the British.[10] The German retreat after the First Battle of the Marne halted at the Aisne River, and the Allies soon caught up, starting the First Battle of the Aisne on September 12. It lasted until September 28, it was indecisive, partially due to machine guns beating back infantry sent to capture enemy positions.[11] In the Battle of Le Cateau, fought on August 26–27, the French Sixth Army prevented the British from being outflanked.[12] The first major Allied attack against German forces since the incarnation of trench warfare on the Western Front, the First Battle of Champagne, lasting from December 20, 1914, until March 17, 1915; it was a German victory, due in part to their machine gun battalions and the well-entrenched German forces.[13]

The indecisive Second Battle of Ypres, from April 22 – May 25, was the site of the first German chlorine gas attack and the only major German offensive on the Western Front in 1915.[14] Ypres was devastated after the battle.[14] The Second Battle of Artois, from May 9 – June 18, the most important part of the Allied spring offensive of 1915, was successful for the Germans, allowing them to advance rather than retreat as the Allies had planned, and Artois would not be in Allied hands again until 1917.[15] The Second Battle of Champagne, from September 25 – November 6, was a general failure, with the French only advancing about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi), and not capturing the German's second line.[4] France suffered over 140,000 casualties, while the Germans suffered over 80,000.[4]

The Battle of the Somme, fought along a 30 kilometres (19 mi) front from north of the Somme River between Arras and Albert. It was fought between July 1 and November 18 and involved over 2 million men. The French suffered 200,000 casualties.[16][17] Little territory was gained, only 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) at the deepest points.

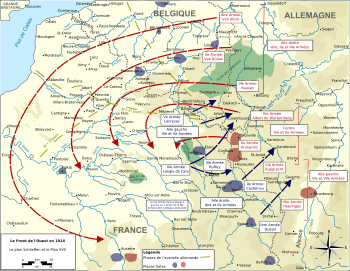

Battle of the Frontiers

The Battle of the Frontiers consisted of five offensives, commanded and planned by French Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre and German Chief-of-Staff Helmuth von Moltke. It was fought in August 1914.[18] These five offensives, Mulhouse, Lorraine, Ardennes, Charleroi, and Mons, were launched almost simultaneously. They were the result of the French Plan XVII and the German plans colliding.[18] The Battle of Mulhouse, on August 7–10, 1914, was envisioned by Joffre to anchor the French recapture of Alsace, but resulted in Joffre holding General Louis Bonneau responsible for its failure and replacing him with General Paul Pau.[19] The Battle of Lorraine, August 14–25, was an indecisive French invasion of that region by General Pau and his Army of Alsace.[20] The Battle of the Ardennes, fought between August 21 and 23 in the Ardennes forests, was sparked by unsuspecting French and German forces meeting, and resulted in a French defeat, forfeiting to the Germans a source of iron-ore.[21] The Battle of Charleroi, which started on August 20 and ended on August 23, was a key battle on the Western Front, and a German victory.[22] General Charles Lanrezac's retreat probably saved the French Army, but Joffre blamed him for the failure of Plan XVII, even though the withdrawal had been permitted.[22]

Race to the Sea

The First Battle of Albert was the first battle in the so-called 'Race to the Sea', so-called because the campaign was attempting to reach the English Channel in an effort to outflank the German army.[23] The First Battle of Albert was fought on September 25–29, 1914, after the First Battle of the Marne and the First Battle of the Aisne. It occurred after both sides realized that a breakthrough was not possible.[24] It was evident that both the French Plan XVII and the German Schlieffen Plan had failed.[24] Both sides then proceeded to attempt to outmaneuver the other, and the battle ended indecisively.[24] The Battle of Arras, which was another attempt on the part of the French to outflank the Germans, was started on October 1.[25] Despite heavy attacks by three corps from the First, Second, and Seventh armies, the French held on to Arras, albeit losing Lens on October 4.[25] The Battle of the Yser, fought between October 18 and November 30, was the northernmost battle in the 'Race to the Sea'.[26] The battle was a German victory, and fighting continued along the Yser River until the final Allied advance that won the war.[26] The last of the 'Race to the Sea' battles, the First Battle of Ypres, started on October 19, marked the formation of a bond between the British and French armies.[27] The battle was an Allied victory and ended, according to France, Britain, and Germany, on November 13, 22, or 30 respectively.[27]

Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun was the longest of the war, lasting from February 21, 1916 until December 18 of the same year. The battle started after a plan by German General Erich von Falkenhayn to capture Verdun and induce a battle of attrition was executed. After a few weeks, the battle became a series of local actions.[28] For the French, the battle signified the strength and fortitude of the French Army.[28] Many military historians consider Verdun the "most demanding" and the "greatest" battle in history.[28]

The German attack on Verdun began with one million troops, led by Crown Prince Wilhelm, facing only about 200,000 French soldiers. The following day, the French were forced to withdraw to their second line of trenches, and on February 24, they were pushed back to their third line, only 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) from Verdun. The newly appointed commander of the Verdun sector, General Philippe Pétain, stated that there would be no more withdrawals, and eventually had every French soldier that was available fighting in the Verdun sector; 259 out of 330 infantry regiments. A single road remained open for trucks, enabling a continual flow of supplies to the defenders.

The German attacking forces were not able to enter the city of Verdun itself and by December 1916 had been forced back beyond the original French trench lines of February. The sector again became a relatively inactive one as the allied focus shifted to the Somme and the Germans adopted a defensive stance. While generally regarded as a tactical victory for the French, the battle caused massive losses on both sides. French casualties had been higher but the original German objective of taking Verdun while destroying the defending army through a battle of attrition had not succeeded.[29]

Nivelle Offensive

In October 1916, troops under Robert Nivelle's command captured Douaumont and other Verdun forts, making him a national hero. Nivelle formulated a plan using his "creeping barrage" tactics that would supposedly end the war in 48 hours with only 10,000 casualties. War Minister Hubert Lyautey, General Philippe Pétain and Sir Douglas Haig were all opposed to the plan, although Aristide Briand supported the "Nivelle Offensive".[30] Lyautey resigned after being shouted down in the Chamber of Deputies for refusing to discuss military aviation secrets. For the offensive in April 1917, one million French soldiers were deployed on a front between Royle and Reims.

The main action of the Nivelle Offensive, the Second Battle of the Aisne, started on April 16, 1917, with the French suffering 40,000 casualties on the first day.[31] By the time the battle was over on May 9, the French had suffered 187,000 casualties, while the Germans suffered 168,000.[31] The Allies eventually suffered over 350,000 casualties fighting the Nivelle Offensive.

Mutinies

In the spring of 1917, after the failed Nivelle Offensive, there were a series of mutinies in the French army.[32] Over 35,000 soldiers were involved with 68 out of 112 divisions affected, but fewer than 3,000 men were punished.[32] Following a series of court-martials, there were 49 documented executions and 2,878 sentences to penal servitude with hard labour. Of the 68 divisions affected by mutinies, 5 had been “profoundly affected”’ 6 had been “very seriously affected”, 15 had been “seriously affected”, 25 were affected by “repeated incidents” and 17 had been affected by “one incident only”, according to statistics compiled by French military historian Guy Pedroncini.[32]

Mutinies began in April 1917 after the failure of the Second Battle of the Aisne, the main action in the Nivelle Offensive. The mutinies started on April 17 and ended on June 30, 1917.[32] They involved units from nearly half of the French infantry divisions stationed on the Western Front. The mutinies were kept secret at the time, and their full extent and intensity were not revealed for a half-century. The more serious episodes involved only a few units; the mutinies did not threaten complete military collapse, but did make the high command reluctant to launch another offensive. The popular cry was to wait for the arrival of millions of fresh U.S. troops. The mutinous soldiers were motivated by despair, not by politics or pacifism. They feared that mass infantry offensives would never prevail over machine guns and artillery. General Pétain restored morale in the summer of 1917 through a combination of rest rotations for front-line units, furloughs home, and stricter discipline.[33] However, Smith has argued that the mutinies were akin to labour strikes and can be considered political. The soldiers demanded not only peace, leave, and better food, and objected to the use of colonial workers on the home front; they were also concerned about the welfare of their families. The courts-martial were merely symbolic, designed to demonstrate the absolute authority of the high command.[34] The British government was alarmed, for it interpreted the mutinies as a sign of deep malaise in French society, and tried to reinvigorate French morale by launching an offensive at Passchendaele (also known as the Third Battle of Ypres).[35]

Kaiserschlacht

The French army was heavily involved in the allies' line of defense during the final German offensives in spring 1918. When British troops were attacked during Operation Michael, 40 French divisions were sent to help them. Those troops finally took part in the battle. Then, the third German offensive was launched against French positions in Champagne. The French troops began to lose ground but eventually, the Germans were stopped by a counterattack led by General Charles Mangin.

In July, a last German assault was launched against the French on the Marne. The German troops were crushed by about 40 French divisions helped by British and American troops. This was a turning point in the war on the Western Front.

The Grand Offensive

During the summer of 1918, General Ferdinand Foch was appointed supreme commander of the allied forces. After the decisive defeat of the Germans at the second Battle of the Marne, Foch ordered an offensive against Amiens. Some French units participated in this battle. Then, a general offensive was launched against the German positions in France. The French First Army helped the British troops in the north, while eight French field armies formed the center of the offensive. An additional army was sent to help the Americans. The French forces were the most numerous of all the allied troops, and during the last stage of the war, they took about 140,000 prisoners. British troops spearheaded the main attack by attacking in Flanders and Western Belgium where they first smashed the Hindenburg line. Meanwhile, the more exhausted French army managed to liberate most of northern France and to enter Belgian territory.

These numerous offensives left the German army on the verge of disaster and when Germany sought for an armistice, British, French and American troops were ready to launch an important offensive in Lorraine, where the Germans were collapsing.

Other campaigns

While the French Army's main commitment was inevitably to the Western Front, significant forces were deployed in other theatres of war. These included the occupation of the German colonies of Togo and Kamerun in West Africa, participation in the Dardanelles and Palestinian campaigns against the Ottoman Empire and a diversionary offensive in the Balkans carried out in conjunction with other Allied forces. The biggest French deployment to help an ally was the mission to Romania, led by Henri Berthelot, during the second half of the war.

The bulk of the French troops utilized in these campaigns were North African and colonial units, both European and indigenous. However the French reinforcements sent to the Italian Front in 1917 following the Battle of Caporetto were drawn from metropolitan French units, marking a diversion of resources from the Western Front.

Equipment

At the outset of the war, the primary French field gun was the French 75, (75mm caliber, entered service in 1897).[36] The French had about 4,000 of these guns, an adequate number, but despite accuracy, quick firing, and lethality against infantry, German howitzers outranged the French 75, which had a range of 7 kilometres (4.3 mi), by 3 kilometres (1.9 mi), and used heavier shells, inflicting more damage than the French guns.[36] In 1913, General Joseph Joffre authorized the limited adoption of the Rimailho Model 1904TR, a howitzer with a range of over 10 kilometres (6.2 mi).[36]

When war broke out in August 1914, the German Army had about 12,000 machine guns, while the British and French armies had a few hundred.[37] French models of machine gun used during the war included the Hotchkiss M1914, the Chauchat, and the St. Étienne Mle 1907.[37]

The first tank was ready for combat by January 1916. Unaware of the British tank development programme, Colonel Jean Baptiste Eugène Estienne persuaded Joffre to begin production of French tanks.[38] An order for 400 Schneider CA1s and 400 Saint-Chamonds was soon placed.[38] The French deployed 128 tanks in April 1917 as part of the Second Battle of the Aisne, but they were unreliable.[38] However, the Renault FT proved more worthy, and the French produced a total of 3,870 tanks by the end of the war.[38]

Grenades came to the attention of German military planners as a result of the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–1905, and by the beginning of the Great War, the Germans had 106,000 rifle grenades and 70,000 hand grenades.[39] The French and Russian armies were better prepared than the British, expecting to find themselves besieging German fortresses, a task suited to the grenade.[39] The French, along with the British, persisted in the use of rifle grenades (they used a special cup for launching) throughout the war, increasing their range from 180 and 200 metres (590 and 660 ft) to 400 metres (1,300 ft).[39]

The mortar also interested the Germans, for a specific use: an invasion of France's eastern front.[40] The advantage of a mortar was that it could be fired from the relative safety of a trench, unlike artillery.[40] At the beginning of World War I, the German Army had a stockpile of 150 mortars, which was a surprise to the French and British. The French were able to use the century-old Coehorn mortars from the Napoleonic Wars.[40][41] Subsequently, the French borrowed the design of the British Stokes Mortar, and collaborated on mortar designs with the British throughout the war. Eventually, large mortars could throw bombs 2 kilometres (1.2 mi).[40]

Despite the technological advances in grenades, machine guns, and mortars, the rifle remained the primary infantry weapon, in large part because other weapons were too cumbersome and unwieldy for an infantryman, and remained the weapon of choice for snipers.[42] Rifles remained virtually the same during the war years, mostly because research tended to be focused on larger weapons and poison gas.[42] The average range of a rifle throughout World War I was 1,400 metres (4,600 ft), but most were only accurate to 600 metres (2,000 ft).[42] The French rifle of choice was the Lebel Model 1886, officially styled the Fusil Modèle 1886-M93, from 1886. Its major design flaw was its eight-round tubular magazine which could cause explosions when the nose of one cartridge was forced onto the base of another.[42] In 1916, the Berthier rifle, officially titled the Fusil d'Infanterie Modele 1907, Transforme 1915, was issued as an improvement; it was clip-loaded.[42] The original, produced in 1907, only held three rounds. Later versions in 1915 introduced the use of spitzer bullets and 1916 increased the clip size to five rounds, and a carbine version of the Berthier, dubbed the Berthier carbine but titled Mousqueton modele 1916, was released in 1916.[42] The carbine was preferred over a 'normal' rifle because of the advantages in handling in a confined space, such as a trench, and was one of the few significant advances in rifle technology, although periscopes and tripods were produced for trench warfare.[42]

Contrary to popular belief, the first country to use chemical warfare in World War I was not Germany, but France, who used tear gas grenades against the German army in August 1914; however, the Germans were the first to seriously research chemical warfare.[43] Poison gas (chlorine) was first used on April 22, 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres, by the German army.[43] April 1915 saw the first innovation in protection against chemical warfare: a cotton pad dipped in bicarbonate of soda, but by 1918, troops on both sides had charcoal respirators.[43] By November 11, 1918, France had suffered 190,000 chemical warfare casualties, including 8,000 dead.[43]

Uniforms

.jpg)

At the outbreak of war the French Army retained the colourful traditional uniforms of the nineteenth century for active service wear. These included conspicuous features such as blue coats and red trousers for the infantry and cavalry.[44] The French cuirassiers wore plumed helmets and breastplates almost unchanged from the Napoleonic period.[45] From 1903 on several attempts had been made to introduce a more practical field dress but these had been opposed by conservative opinion both within the army and amongst the public at large. In particular, the red trousers worn by the infantry became a political debating point.[46] Adolphe Messimy who was briefly Minister of War in 1911-1912 stated that "This stupid blind attachment to the most visible of colours will have cruel consequences"; however, in the following year, one of his successors, Eugène Étienne, declared "Abolish red trousers? Never!"[47]

In order to appease traditionalists, a new cloth was devised woven from red, white and blue threads, known as "Tricolour cloth", resulting in a drab purple-brown colour. Unfortunately the red thread could only be produced with a dye made in Germany, so only the blue and white threads were used. The adoption of the blue-grey uniform (known as "horizon-blue" because it was thought to prevent soldiers from standing out against the skyline) had been approved by the French Chamber of Deputies on 10 July 1914[48] but new issues had not been possible before the outbreak of war a few weeks later.[49]

The very heavy French losses during the Battle of the Frontiers can be attributed in part to the high visibility of the French uniforms, combined with peacetime training which placed emphasis on attacking in massed formations.[50] The shortcomings of the uniforms were quickly realized and during the first quarter of 1915 general distribution of horizon-blue clothing in simplified patterns had been undertaken. The long established infantry practice of wearing greatcoats for field service, buttoned back when on the march, was continued in the trenches. British-style puttees were issued in place of leather gaiters from October 1914.[51] The French Army was the first to introduce steel helmets for protection against shrapnel, and by December 1915 more than three million "Adrian" helmets had been manufactured.[52]

The horizon-blue uniform and Adrian helmet proved sufficiently practical to be retained unchanged for the remainder of the war, although khaki of a shade described as "mustard" was introduced after December 1914 for the North African and colonial troops serving in France.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to French Army during World War I. |

References

- Duffey, Michael (2004-03-27). "Feature Articles: The Causes of World War One". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- Sumner, Ian. French Poilu 1914-18. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-84603-332-2.

- pages 215, 217 and 218, Vol. XXX, Encyclopædia Britannica, 12th Edition, 1922

- Rickard, J (2007-08-16). "Second Battle of Champagne, 25 September-6 November 1915". historyofwar.com. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-11). "Who's Who – Joseph Joffre". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-11). "Who's Who – Robert Nivelle". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-11). "Who's Who: Henri-Philippe Petain". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- Duffy, Michael (2002-10-06). "The Siege of Maubeuge". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- Duffy, Michael (2002-03-20). "Battles – The Battle of Guise, 1914". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-11). "Battles: The First Battle of the Marne, 1914". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-11). "Battles – The First Battle of the Aisne". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-11). "Battles: The Battle of Le Cateau, 1914". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- "First Battle of Champagne begins". history.com. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-11). "Battles: The Second Battle of Ypres". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Rickard, J (2007-08-26). "Second battle of Artois, 9 May-18 June 1915". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-11). "Battles: The Battle of the Somme, 1916". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- "The Battle of the Somme". pbs.org. Community Television of Southern California. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-12). "Battles – The Battle of the Frontiers, 1914". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- "This Day in History 1914: Battle of Mulhouse begins". history.com. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-19). "Battles: The Invasion of Lorraine, 1914". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-19). "Battles: The Battle of the Ardennes, 1914". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- Duffy, Michael (2003-01-12). "Battles: The Battle of Charleroi, 1914". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- Duffy, Michael (2002-10-13). "Race to the Sea". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-19). "Battles – The First Battle of Albert". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Duffy, Michael (2001-08-19). "Battles – The Battle of Arras, 1914". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Rickard, J (2007-08-24). "Battle of the Yser, 18 October-30 November 1914". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Rickard, J (2007-08-25). "First battle of Ypres, 19 October-22 November 1914". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- "The Great War , Maps & Battles , The Battle of Verdun". pbs.org. Community Television of Southern California. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- John Keegan, pages 300-308 "The First World War", ISBN 0 09 1801788

- "The Nivelle Offensive". historylearningsite.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- Duffy, Michael (2002-11-29). "Battles – The Second Battle of the Aisne, 1917". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- "Mutiny in the French Army". historylearningsite.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Bentley B.; Gilbert and Paul P. Bernard, "The French Army Mutinies of 1917," Historian (1959) 22#1 pp 24-41

- Leonard V. Smith, "War and 'Politics': The French Army Mutinies of 1917," War in History (1995( 2#2 pp 180-201.

- David French, "Watching the Allies: British Intelligence and the French Mutinies of 1917," Intelligence & National Security (1991) 6#3 pp 573-592

- Miquel, Pierre (1998). "France at War – The Politics of French Military Leadership, 1914–1918". worldwar1.com. The Great War Society. Archived from the original on 2009-04-18. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- Duffy, Michael (2003-05-03). "Weapons of War: Machine Guns". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- Duffy, Michael (2002-05-05). "First World War.com – Weapons of War – Tanks". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- Duffy, Michael (2003-07-26). "Weapons of War: Grenades". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- Duffy, Michael (2002-01-10). "Weapons of War – Trench mortars". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- Baker, Chris. "The Trench Mortar Batteries". 1914-1918.net. Archived from the original on 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- Duffy, Michael (2002-07-28). "Weapons of War – Rifles". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- Duffy, Michael (2002-05-05). "Weapons of War: Poison Gas". First World War.com. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- Mirouze, Laurent (2007). The French Army in the First World War - to Battle 1914. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-3-902526-09-0.

- Louis Delperier, pages 60-70 "Les Cuirassiers 1845-1918", Argout-Editions Paris 1981

- Mirouze, Laurent (2007). The French Army in the First World War - to Battle 1914. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-3-902526-09-0.

- Sumner, Ian (2012), They Shall Not Pass: The French Army on the Western Front 1914-1918, Pen & Sword Military, ISBN 978-1848842090 (p. 85)

- page 64 Militaria Magazine No 358, Mai 2015

- Sumner, p. 86

- Barbara W. Tuchman, page 274 "The Guns of August", Constable & Co. Ltd 1962

- Sumner, p. 40

- Andre Jouineau, page 4 "Officers and Soldiers of the French Army 1915 to Victory, ISBN 978-2-35250-105-3

Further reading

- Arnold, Joseph C, "French tactical doctrine 1870–1914", Military Affairs: The Journal of Military History, Including Theory and Technology. (1978): 61-67, doi:10.2307/1987399. Link in JSTOR

- Cabanes Bruno. August 1914: France, the Great War, and a Month That Changed the World Forever (2016) argues that the extremely high casualty rate in very first month of fighting permanently transformed France.

- Clayton, Anthony. Paths of glory: the French Army 1914–18, London: Cassell, 2003

- Delvert, Charles (translator Ian Sumner). From Marne to Verdun: A French Officer's Diary, Pen & Sword Military (2016) ISBN 978-1473823792

- Doughty, Robert A. Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War (2008), 592pp; excerpt and text search

- Fogarty, Richard S. Race and war in France: Colonial subjects in the French army, 1914–1918 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008)

- Gilbert, Bentley B. and Bernard, Paul P. "The French Army Mutinies of 1917", The Historian (1959) Volume 22 Issue 1, pp 24–41, doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1959.tb01641.x

- Herwig, Holger H. and Neil Heyman. Biographical Dictionary of World War I (1982), 425pp

- Horne, Alistair. The French Army and Politics, 1870–1970, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1984

- Porch, Douglas. The March to the Marne: The French Army 1871–1914, Cambridge University Press (2003) ISBN 978-0521545921

- Shapiro, Ann‐Louise. "Fixing History: Narratives of World War I in France." History and Theory 36.4 (1997): 111–130. online

- Sumner, Ian. The First Battle of the Marne: The French 'Miracle' Halts the Germans (Campaign), Osprey Publishing (2010) ISBN 978-1846035029

- Sumner, Ian. The French Army: 1914–18, Osprey Publishing (1995) ISBN 1-85532-516-0

- Sumner, Ian. The French Army at Verdun (Images of War), Pen & Sword Military (2016) ISBN 978-1473856158

- Sumner, Ian. The French Army in the First World War (Images of War), Pen & Sword Military (2016) ISBN 978-1473856196

- Sumner, Ian. French Poilu 1914–18 (Warrior), Osprey Publishing (2009) ISBN 978-1846033322

- Sumner, Ian. They Shall Not Pass: The French Army on the Western Front 1914–1918, Pen & Sword Military (2012) ISBN 978-1848842090