Property rights (economics)

Property rights are theoretical socially-enforced constructs in economics for determining how a resource or economic good is used and owned.[1] Resources can be owned by (and hence be the property of) individuals, associations, collectives, or governments.[2] Property rights can be viewed as an attribute of an economic good. This attribute has four broad components[3] and is often referred to as a bundle of rights:[4]

- the right to use the good

- the right to earn income from the good

- the right to transfer the good to others, alter it, abandon it, or destroy it (the right to ownership cessation)

- the right to enforce property rights

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

By application |

|

Notable economists |

|

Lists |

|

Glossary |

|

In economics, property is usually considered to be ownership (rights to the proceeds generated by the property) and control over a resource or good. Many economists effectively argue that property rights need to be fixed and need to portray the relationships among other parties in order to be more effective.[5]

Regimes

Property rights to a good must be defined, their use must be monitored, and possession of rights must be enforced. The costs of defining, monitoring, and enforcing property rights are termed transaction costs.[6][7] Depending on the level of transaction costs, various forms of property rights institutions will develop. Each institutional form can be described by the distribution of rights.

The following list is ordered from no property rights defined to all property rights being held by individuals[8]

- Nobodies property (res nullius) is not 'owned' by anyone. It is non-excludable (no one can exclude anyone else from using it), non-transferable, but may be rival (one person's use of it reduces the quantity available to other users). Open-access property is not managed by anyone, and access to it is not controlled. There is no constraint on anyone using open-access property (excluding people is either impossible or prohibitively costly). Examples of currently open-access property is outer space or ocean fisheries (outside of territorial borders).

Open-access property may exist because ownership has never been established, granted, by laws within a particular country, or because no effective controls are in place, or feasible, i.e., the cost of exclusivity outweighs the benefits. The government can sometimes effectively convert open access property into private, common, or public property through the land grant process, by legislating to define public/private rights previously not granted.

— Kevin Guerin, [9]

- Public property (also known as state property) is property that is publicly owned, but its access and use are managed and controlled by a government agency or organization granted such authority. An example is a national park or a state-owned enterprise.[9]

- Common property or collective property is property that is owned by a group of individuals. Access, use, and exclusion are controlled by the joint owners. True commons can break down, but, unlike open-access property, common property owners have greater ability to manage conflicts through shared benefits and enforcement.[9]

- Private property is both excludable and rival. Private property access, use, exclusion and management are controlled by the private owner or a group of legal owners.

The environment

Implicit or explicit property rights can be created by regulating the environment, either through prescriptive command and control approaches (e.g. limits on input/output/discharge quantities, specified processes/equipment, audits) or by market-based instruments (e.g. taxes, transferable permits or quotas),[9] and more recently through cooperative, self-regulatory, post-regulatory and reflexive law approaches.[10] See the Conservation Property Right

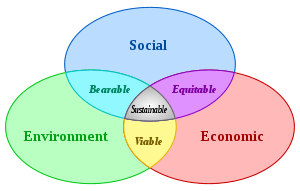

It has been proposed by Ronald Coase that clearly defining and assigning property rights would resolve environmental problems by internalizing externalities and relying on incentives of private owners to conserve resources for the future. At common law nuisance and tort law allows adjacent property holders to seek compensation when individual actions diminish the air and water quality for adjacent landowners. Critics of this view argue that this assumes that it is possible to internalize all environmental benefits, that owners will have perfect information, that scale economies are manageable, transaction costs are bearable, and that legal frameworks operate efficiently.[9]

Literature

In 2013 researchers[11] produced an annotated bibliography on the property rights literature concerned with two principal outcomes: (a) reduction in investors risk and increase in incentives to invest, and (b) improvements in household welfare; the researchers explored the channels through which property rights affect growth and household welfare in developing countries. They found that better protection of property rights can affect several development outcomes, including better management of natural resources.

Despite the overwhelming evidence on the economic relevance of property rights however, only recently economists have begun to study their determinants by looking at the trade-off between the dispersed coercive power in a state of anarchy and the predation by a central authority. To illustrate, incomplete property rights allow agents with valuation lower than that of the original owners of economic value to inefficiently expropriate them distorting in this way their investment and effort exertion decisions. When instead, the state is entrusted the power to protect property, it might directly expropriate private parties if not sufficiently constrained by an efficient political process.[12] The necessity of strong protection of property for efficiency has been however criticized by a vast legal scholarship, originated from the seminal contribution by Guido Calabresi and Douglas Melamed.[13] These authors argue that in the face of transaction costs sufficiently sizeable to prevent consensual trade, legalized private expropriation in the form of, for instance, liability rules can be welfare-increasing. Carmine Guerriero blends these two different strands of literature by linking property rights protection, transaction costs, and preference heterogeneity.[14] To elaborate, when property is fully protected, some agents with valuation higher than that of the original owners will be unable to legally acquire value because of sizable transaction costs. When the protection of property is weak instead, low-valuation potential buyers inefficiently expropriate original owners. Hence, a rise in the heterogeneity of the potential buyers' valuations makes inefficient expropriation by low-valuation potential buyers be more important from a social welfare point of view than inefficient exclusion from trade and so induces stronger property rights. Crucially, this prediction survives even after considering production and investment activities and it is consistent with a novel dataset on the rules on the acquisition of ownership through adverse possession and on the use of government takings to transfer real property from a private party to another private party prevailing in 126 jurisdictions. These data measure “horizontal property rights” and thus the extent of protection of property from “direct and indirect private takings,” which are ubiquitous forms of expropriation that occur daily within the rule of law and are thus different from predation by the state and the elites, which is much less common but has been the focus of the economics literature. To capture preference diversity, the author uses the contemporary genetic diversity, which is a primitive metric of the genealogical distance between populations with a common ancestor and so of the differences in characteristics transmitted across generations, such as preferences.[15] Regression analysis reveals that the protection of the original owners' property rights is the strongest where contemporary genetic diversity is the largest. Evidence from several different identification strategies suggests that this relationship is indeed causal.

Property rights approach to the theory of the firm

The property rights approach to the theory of the firm based on the incomplete contracting paradigm was developed by Sanford Grossman, Oliver Hart, and John Moore.[16][17] These authors argue that in the real world, contracts are incomplete and hence it is impossible to contractually specify what decisions will have to be taken in any conceivable state of the world. There will be renegotiations in the future, so parties have insufficient investment incentives (since they will only get a fraction of the investment's return in future negotiations); i.e., there is a hold-up problem. Hence, property rights matter, because they determine who has control over future decisions if no agreement will be reached. In other words, property rights determine the parties' future bargaining positions (while their bargaining powers, i.e. their fractions of the renegotiation surplus, are independent of the property rights allocation).[18] The property rights approach to the theory of the firm can thus explain pros and cons of integration in the context of private firms. Yet, it has also been applied in various other frameworks such as public good provision and privatization.[19][20] The property rights approach has been extended in many directions. For instance, some authors have studied different bargaining solutions,[21][22] while other authors have studied the role of asymmetric information.[23]

Role of property rights in economic and political development

Classical economists such as Adam Smith and Karl Marx generally recognize the importance of property rights in the process of economic development, and modern mainstream economics agree with such a recognition.[24] A widely accepted explanation is that well-enforced property rights provide incentives for individuals to participate in economic activities, such as investment, innovation and trade, which lead to a more efficient market.[25] The development of property rights in Europe during the Middle Ages provides an example.[26] During this epoch, full political power came into the hands of hereditary monarchies, which often abused their power to exploit producers, to impose arbitrary taxes, or to refuse to pay their debts. The lack of protection for property rights provided little incentive for landowners and merchants to invest in land, physical or human capital, or technology. After the English Civil War of 1642-1646 and the Glorious Revolution of 1688, shifts of political power away from the Stuart monarchs led to the strengthening of property rights of both land and capital owners. Consequently, rapid economic development took place, setting the stage for Industrial Revolution.

Property rights are also believed to lower transaction costs by providing an efficient resolution for conflicts over scarce resources.[27] Empirically, using historical data of former European colonies, Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson find substantial evidence that good economic institutions – those that provide secure property rights and equality of opportunity – lead to economic prosperity.[28]

Property rights might be closely related to the evolution of political order, due to their protections of an individual's claims on economic rents. North, Wallis and Weingast argue that property rights originate to facilitate elites' rent-seeking activities. Particularly, the legal and political systems that protect elites' claims on rent revenues form the basis of the so-called "limited access order", in which non-elites are denied access to political power and economic privileges.[29] In a historical study of medieval England, for instance, North and Thomas find that the dramatic development of English land laws in the 13th century resulted from elites' interests in exploiting rent revenues from land ownership after a sudden rise in land price in the 12th century.[30] In contrast, the modern "open access order", which consists of a democratic political system and a free- market economy, usually features widespread, secure and impersonal property rights. Universal property rights, along with impersonal economic and political competition, downplay the role of rent-seeking and instead favor innovations and productive activities in a modern economy.[31]

See also

- Alienation (property law)

- Bundle of rights

- Common ownership

- Commons

- Economic system

- Intellectual property

- Land tenure

- Land titling

- Law and economics

- Means of production

- Natural and legal rights

- Open-access

- Personal property

- Public property

- Private property

- Property income

- Right to property

- Social ownership

- State ownership

- Taxation as theft

References

- Alchian, Armen A. "Property Rights". New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, Second Edition (2008).

A property right is a socially enforced right to select uses of an economic good.

- Alchian, Armen A. (2008). "Property Rights". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0-86597-665-8. OCLC 237794267. Archived from the original on 2007-04-09.

- • "Economics Glossary". Retrieved 2007-01-28.

• Thrainn Eggertsson (1990). Economic behavior and institutions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34891-1.

• Dean Lueck (2008). "property law, economics and," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. - Klein, Daniel B. and John Robinson. "Property: A Bundle of Rights? Prologue to the Symposium." Econ Journal Watch 8(3): 193–204, September 2011.

- An, Zhiyong (1 November 2013). "Private Property Rights, Investment Patterns, and Asset Structure". Economics & Politics. 25 (3): 481–495. doi:10.1111/ecpo.12021.

- Barzel, Yoram (April 1982). "Measurement Costs and the Organization of Markets". Journal of Law and Economics. 25 (1): 27–48. doi:10.1086/467005. ISSN 0022-2186. JSTOR 725223.

- Douglas Allen (1991). What are Transaction Costs? (Research in Law and Economics). Jai Pr. ISBN 978-0-7623-1115-6.

- Daniel W. Bromley (1991). Environment and Economy: Property Rights and Public Policy. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 978-1-55786-087-3.

- Guerin, K. (2003). Property Rights and Environmental Policy: A New Zealand Perspective. Wellington, New Zealand: NZ Treasury

- See literature on post-regulatory approaches and reflexive law, especially literature from Gunther Teubner. See also the example of the 'conservation property right'

- Mike Denison and Robyn Klingler-Vidra, October 2012, Annotated Bibliography for Rapid Review on Property Rights, Economics and Private Sector Professional Evidence and Applied Knowledge Services (EPS PEAKS)https://partnerplatform.org/?tcafmd80

- Besley, Timothy, and Maitreesh Ghatak (2010). Handbook of Development Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 4525–4595.

- Calabresi, Guido, and Melamed, A. Douglas (1972). "Property Rules, Liability Rules and Inalienability: One View of the Cathedral". Harvard Law Review. 85 (6): 1089–1128. doi:10.2307/1340059. JSTOR 1340059.

- Guerriero, Carmine (2016). "Endogenous Property Rights". Journal of Law and Economics. 59 (2): 313–358. doi:10.1086/686985.

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luca L., Paolo Menozzi, and Alberto Piazza (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Grossman, Sanford J.; Hart, Oliver D. (1986). "The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration". Journal of Political Economy. 94 (4): 691–719. doi:10.1086/261404. hdl:1721.1/63378. ISSN 0022-3808.

- Hart, Oliver; Moore, John (1990). "Property Rights and the Nature of the Firm". Journal of Political Economy. 98 (6): 1119–1158. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.472.9089. doi:10.1086/261729. ISSN 0022-3808.

- Schmitz, Patrick W. (2013). "Bargaining position, bargaining power, and the property rights approach" (PDF). Economics Letters. 119 (1): 28–31. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2013.01.011.

- Hart, Oliver; Shleifer, Andrei; Vishny, Robert W. (1997). "The Proper Scope of Government: Theory and an Application to Prisons". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 112 (4): 1127–1161. doi:10.1162/003355300555448. ISSN 0033-5533.

- Hoppe, Eva I.; Schmitz, Patrick W. (2010). "Public versus private ownership: Quantity contracts and the allocation of investment tasks". Journal of Public Economics. 94 (3–4): 258–268. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.11.009.

- Meza, David de; Lockwood, Ben (1998). "Does Asset Ownership Always Motivate Managers? Outside Options and the Property Rights Theory of the Firm". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 113 (2): 361–386. doi:10.1162/003355398555621. ISSN 0033-5533.

- Chiu, Y. Stephen (1998). "Noncooperative Bargaining, Hostages, and Optimal Asset Ownership". The American Economic Review. 88 (4): 882–901. JSTOR 117010.

- Schmitz, Patrick W (2006). "Information Gathering, Transaction Costs, and the Property Rights Approach". American Economic Review. 96 (1): 422–434. doi:10.1257/000282806776157722.

- Besley, Timothy; Maitreesh, Ghatak (2009). Rodrik, Dani; Rosenzweig, Mark R (eds.). "Property Rights and Economic Development". Handbook of Development Economics. V: 4526–28.

- Acemoglu, Daron; Johnson, Simon; Robinson, James (2005). "Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth". Handbook of Economic Growth. 1: 397.

- Acemoglu, Daron; Johnson, Simon; Robinson, James A. (2005). Chapter 6 Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth. Handbook of Economic Growth. 1. pp. 385–472. doi:10.1016/S1574-0684(05)01006-3. ISBN 978-0-444-52041-8.

- Alchian, Armen; Demsetz, Harold (1973). "The Property Right Paradigm". The Journal of Economic History. 33 (1): 16–27. doi:10.1017/S0022050700076403.

- Acemoglu, Daron; Johnson, Simon; Robinson, James (2005). "Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth". Handbook of Economic Growth. 1. pp. 385–472.

- North, Douglass C; Wallis, John J; Weingast, Barry R (2006). "A conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history". National Bureau of Economic Research. 12795: 32–33.

- North, Douglass C; Thomas, Robert P (1971). "The Rise and Fall of the Manorial System: A Theoretical Model". The Journal of Economic History. 31 (4): 777–803. doi:10.1017/S0022050700074623.

- North, Douglass C; Wallis, John J; Weingast, Barry R (2009). "Violence and the Rise of Open-Access Orders". Journal of Democracy. 20 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1353/jod.0.0060.