Finnish Air Force

The Finnish Air Force (FAF or FiAF) (Finnish: Ilmavoimat ("Air Forces"), Swedish: Flygvapnet) ("Air Arm") is one of the branches of the Finnish Defence Forces. Its peacetime tasks are airspace surveillance, identification flights, and production of readiness formations for wartime conditions.[1] The Finnish Air Force was founded on 6 March 1918.

| Finnish Air Force | |

|---|---|

| Ilmavoimat (Finnish) Flygvapnet (Swedish) | |

Finnish Air Force emblem | |

| Active | 6 March 1918—present |

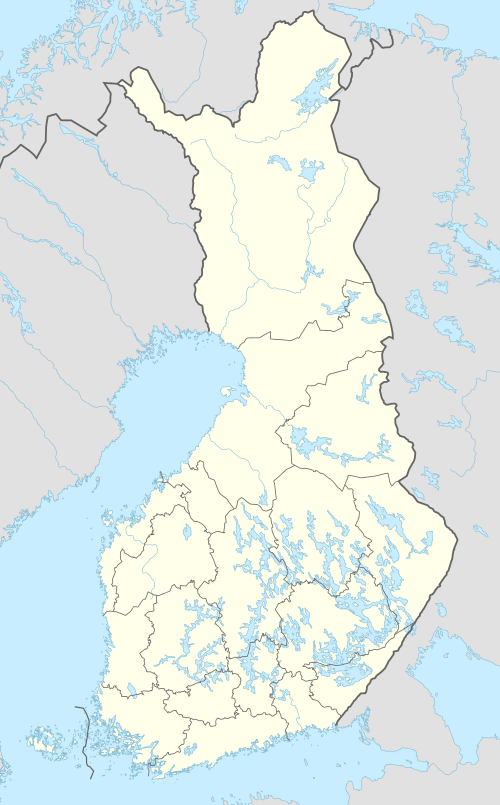

| Country | |

| Type | Air force |

| Role | Aerial warfare |

| Size | 3,100 active personnel, 38,000 reserve personnel |

| Motto(s) | Qualitas Potentia Nostra Quality is our Strength |

| Equipment | 134 aircraft |

| Engagements | Finnish Civil War Winter War Continuation War Lapland War |

| Website | ilmavoimat |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | Major General Pasi Jokinen |

| Notable commanders | Arne Somersalo Jarl Lundqvist Jarmo Lindberg |

| Insignia | |

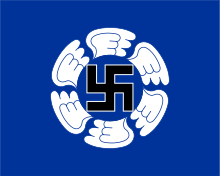

| Roundel |  |

| Aviator wings | |

History

The first steps in the history of Finnish aviation were taken with Russian aircraft. The Russian military had a number of early designs stationed in the country, which until the Russian Revolution of 1917 had been part of the Russian Empire. Soon after the declaration of independence the Finnish Civil War erupted, in which the Soviets sided with the Reds – the socialist rebels with ties to the Bolshevik Party. Finland's White Guard, the Whites, managed to seize a few aircraft from the Soviets, but were forced to rely on foreign pilots and aircraft. Sweden refused to send men and material, but individual Swedish citizens came to the aid of the Whites. The editor of the Swedish daily magazine Aftonbladet, Waldemar Langlet, bought a N.A.B. Albatros aircraft from the Nordiska Aviatik A.B. factory with funds gathered by the Finlands vänner ("Friends of Finland") organization. This aircraft, the first to arrive from Sweden, was flown via Haparanda on 25 February 1918 by Swedish pilot John-Allan Hygerth (who on March 10 became the first commander of the Finnish Air Force) and Per Svanbäck. The aircraft made a stop at Kokkola and had to make a forced landing in Jakobstad when its engine broke down. It was later given the Finnish Air Force designation F.2 ("F" coming from the Swedish word "Flygmaskin", meaning "aircraft").[2]

Swedish count Eric von Rosen gave the Finnish White government its second aircraft, a Thulin Typ D.[3] Its pilot, Lieutenant Nils Kindberg, flew the aircraft to Vaasa on 6 March 1918, carrying von Rosen as a passenger. As this gift ran counter to the will of the Swedish government, and no flight permit had been granted, it led to Kindberg being fined 100 Swedish crowns for leaving the country without permission. This aircraft is considered by some to be the first aircraft of the Finnish Air Force, which did not exist during the Civil War, while the Red side flew a few aircraft with the help of some Russian pilots. The von Rosen aircraft was given the designation F.1.[2] The Finnish Air Force is one of the oldest air forces of the world – the British RAF was founded as the first independent branch on 1 April 1918 and the Swedish Flygvapnet on 1 July 1926.

Von Rosen had painted his personal good luck charm on the Thulin Typ D aircraft. This charm – a blue swastika, the ancient symbol of the sun and good luck, with no political connotation at the time – was adopted as the insignia of the Finnish Air Force. The white circular background was created when the Finns painted over the advertisement from the Thulin air academy.[4] The swastika was officially taken into use after an order by Commander-in-Chief C. G. E. Mannerheim on 18 March 1918. The FAF changed its aircraft insignia, which resembled the unrelated Third Reich swastika, after 1944, due to an Allied Control Commission decree[5] prohibiting Fascist organizations.[5] It nevertheless continues to be featured in some unit emblems, unit flags and decorations, including on uniforms. In 2020 it was reported that the FAF had "quietly stopped" using the symbol in the emblem of the Air Force Command.[6]

The F.1 aircraft was destroyed in an accident, killing its crew, not long after it had been handed over to the Finns. On 7 September 1920, two newly purchased Savoia flying boats crashed in the Swiss Alps en route to Finland, killing all on-board (three Finns and one Italian). This day has since been the memorial day for fallen pilots.

The Finnish Air Force assigns the matriculation numbers to its aircraft by assigning each type a two-letter code following by dash and an individual aircraft number. The two-letter code usually refers to the aircraft manufacturer or model, such as HN for F/A-18 Hornet, DK for Saab 35 Draken, VN for Valmet Vinka etc.

The Finnish Civil War 1918

The air activity of the Reds

Most of the airbases that the Russians had left in Finland had been taken over by Whites after the Russian pilots had returned to Russia.

The Reds were in possession of a few airbases and a few Russian aircraft, mainly amphibious aircraft. They had 12 aircraft in all. The Reds did not have any pilots themselves, so they hired some of the Russian pilots that had stayed behind. On 24 February 1918 five aircraft arrived to Viipuri, and were quickly transferred to Riihimäki.

The Reds created air units in Helsinki, Tampere, Kouvola, and Viipuri. There were no overall headquarters, but the individual units served under the commander of the individual front line. A flight school was created in Helsinki, but no students were trained there before the fall of Helsinki.

Two of the aircraft, one reconnaissance aircraft (Nieuport 10) and one fighter aircraft (Nieuport 17) that had arrived to Riihimäki were sent to Tampere, and three to Kouvola. Four Russian pilots and six mechanics also arrived to Tampere. The first war sortie was flown on March 1, 1918 over Naistenlahti.

It seems like the Reds also operated two aircraft over the Eastern front. The Reds mainly performed reconnaissance, bombing sorties, spreading of propaganda leaflets, and artillery spotting. The Reds' air activity was not particularly successful. Their air operations suffered from bad leadership, worn-out aircraft, and the un-motivated Russian pilots. Some of the aircraft were captured by the Whites, while the rest were destroyed.

The air activity of the Whites

In January 1918 the Whites did not have a single aircraft, let alone pilots, so they asked the Swedes for help. Sweden was a neutral nation and thus could not send any official help. Sweden also forbade its pilots to aid Finland.

Despite this official stance, however, one Morane-Saulnier Parasol, and three N.A.B. Albatros arrived from Sweden by the end of February 1918. Two of the Albatross aircraft were gifts from private citizens supporting the White Finnish cause, while the third was bought. It was initially meant that the aircraft would be used to support the air operations of the Whites, but the aircraft ultimately proved unsuitable.

Along with aircraft shortages, the Whites also did not have any personnel, so all the pilots and mechanics also came from Sweden. One of the Finnish Jägers, Lieutenant Bertil Månsson, had been given pilot training in Imperial Germany, but he stayed behind in Germany, trying to secure further aircraft deals for Finland.

During the Civil War the White Finnish Air Force consisted of:

- 29 Swedes (16 pilots, two observers and 11 mechanics). Of the pilots, only 4 had been given military training, and one of them was operating as an observer.

- 2 Danes (one pilot, one observer)

- 7 Russians (six pilots, one observer)

- 28 Finns (four pilots of whom two were military trained, six observers, two engineers and 16 mechanics).

The air activity consisted mainly of reconnaissance sorties. The Germans brought several of their own aircraft, but they did not contribute much to the overall outcome of the war.

The first Air Force Base of independent Finland was founded on the shore near Kolho. The base could operate three aircraft. The first aircraft was brought by rail on March 7, 1918, and on March 17, 1918 took off from the base for the first time. In 1918, the Finns took over nine Russian Stetinin M-9 aircraft that had been left behind.

The first air operation of the Whites during the war was flown over Lyly. It was a reconnaissance gathering mission as the front line moved south. As the line neared Tampere, the AFB was moved first to Orivesi and then to Kaukajärvi near Tampere as well. The contribution of the White air force during the war was almost insignificant.

From March 10, 1918, the Finnish Air Force was led by the Swedish Lt. John-Allan Hygerth. He was however replaced on April 18, 1918, due to his unsuitability for the position and numerous accidents. His job was taken over by the German Captain Carl Seber, who commanded the air force from April 28, 1918 until December 13, 1918.

By the end of the Civil War, the Finnish Air Force had 40 aircraft, of which 20 had been captured from the Reds (the Reds did not operate this many aircraft, but some had been found abandoned on the Åland Islands). Five of the aircraft had been flown by the Allies from Russia, four had been gifts from Sweden and eight had been bought from Germany.

Winter War 1939–1940

The Winter War began on 30 November 1939, when the Soviet Air Force bombed 21 Finnish cities and municipalities. The Soviet Union is estimated to have had about 5,000 aircraft in 1939, and of these, some 700 fighters and 800 medium bombers were brought to the Finnish front to support the Red Army's operations. As with most aerial bombardment of the early stages of World War II, the damage to Finnish industry and railways was quite limited.

At the beginning of the Winter War, the Finnish Air Force was equipped with only 18 Bristol Blenheim bombers and 46 fighters (32 modern Fokker D.XXIs and 14 obsolete Bristol Bulldogs). There were also 58 liaison aircraft, but 20 of these were only used for messengers. The most modern aircraft in the Finnish arsenal were British-designed and -built Bristol Blenheim bombers. The primary fighter aircraft was the Fokker D.XXI, a cheap but maneuverable design with fabric-covered fuselage and fixed landing gear. On paper, this force should have been no match for the attacking Soviet Red Air Force. However, the Finnish Air Force had already adopted the Finger-four formation in the mid-1930s,[7][8] which was to be found to be much more effective formation than the Vic formation that many other countries were still using when World War II began.

To prevent their aircraft from being destroyed on the ground, the Finns spread out their aircraft to many different airfields and hid them in the nearby forests. The Finns constructed many decoys and built shrapnel protection walls for the aircraft. Soviet air raids on Finnish airfields usually caused little or no damage as a result, and often resulted in interception of the attackers by the Finns as the bombers flew homeward.

As the war progressed, the Finns tried desperately to purchase aircraft wherever there were any to be found. This policy resulted in a very diverse aircraft inventory, which caused some major logistical problems until the inventory became more standardized. The Finnish Air Force included numerous American, British, Czechoslovakian, Dutch, French, German, Italian, Soviet, and Swedish designs. Other countries, like South Africa and Denmark, sent aircraft to assist in the Finnish war effort. Many of these purchases and gifts did not arrive until the end of the hostilities, but were to see action later during the Continuation and Lapland wars.

To make up for its weaknesses (few and obsolete fighters) the FAF mainly focused on attacking enemy bombers from directions that were disadvantageous to the enemy. Soviet fighters were usually superior in firepower, speed and agility, and were to be avoided unless the enemy was in a disadvantageous position.

As a result of these tactics, the Finnish Air Force managed to shoot down 218 Soviet aircraft during the Winter War while losing only 47 to enemy fire. Finnish anti-aircraft guns also had 314 confirmed downed enemy planes. 30 Soviet planes were captured – these were "kills" that landed more or less intact within Finland and were quickly repaired.

Continuation War 1941–1944

The Finnish Air Force was better prepared for the Continuation War. It had been considerably strengthened and consisted of some 550 aircraft, though many were considered second-rate and thus "exportable" by their countries of origin. Finland purchased a large number of aircraft during the Winter War, but few of those reached service during the short conflict. Politics also played a factor, since Hitler did not wish to antagonize the Soviet Union by allowing aircraft exports through German-controlled territory during the conflict. In addition to Fokker fighters and Bristol Blenheim bombers built under license, new aircraft types were in place by the time hostilities with Soviet Union resumed in 1941. Small numbers of Hawker Hurricanes arrived from the United Kingdom, Morane-Saulnier M.S.406s from France, Fiat G.50s from Italy, and one liaison aircraft. Numerous Brewster F2A Buffaloes from the neutral USA strengthened the FAF. A few dozen Curtiss Hawk 75s captured by the Germans in France and Norway were sold to Finland when Germany began warming up its ties with Finland. Captured Tupolev SBs, Ilyushin DB-3s, and Polikarpov I-153s were reconditioned for service.

The FAF proved capable of holding its own in the upcoming battles with the Red Air Force. Older models, such as the Fokker D.XXI and Gloster Gladiator, had been replaced with new aircraft in front-line combat units.

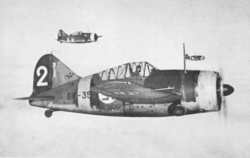

The FAF's main mission was to achieve air superiority over Finland and prevent Soviet air power from reinforcing their front lines. The fighter squadrons were very successful in the Finnish offensive of 1941. A stripped-down, more maneuverable, and significantly lightened version of the American Brewster Buffalo was the FAF's main fighter until 1943. Results with this fighter were very good, even though the type was considered to be a failure in the US Navy and with British and Dutch Far East forces. In Finnish use, the Brewster had a victory rate of 32:1 – 459 kills to 15 losses. German Bf 109s replaced the Brewster as the primary front-line fighter of the FAF in 1943, though the Buffalos continued in secondary roles until the end of the wars. Other types, especially the Italian Fiat G.50 and Curtiss Hawk 75, also proved capable in the hands of well-trained Finnish pilots. Various Russian designs also saw action when lightly damaged "kills" were repaired and made airworthy.

Dornier Do 17s (received as a gift from Hermann Göring in 1942) and Junkers Ju 88s improved the bombing capability of the Finnish Air Force. The bomber force was also strengthened with a number of captured Soviet bombers, which had been taken in large numbers by the Germans during Operation Barbarossa. The bomber units flew assorted missions with varying results, but a large part of their time was spent in training, waiting to use their aircraft until the time required it. Thus the bomber squadrons of Flying Regiment 4 were ready for the summer battles of 1944, which included for example the Battle of Tali-Ihantala.

While the FAF was successful in its mission, the conditions were not easy. Spare parts for the FAF planes were scarce — parts from the US (Buffalo and Hawk), Britain (Hurricanes), and Italy (G.50) were unavailable for much of the war. Repairs took often a long time, and the State Aircraft Factory was burdened with restoration/repair of captured Soviet planes, foreign aircraft with many hours of flight time, and the development of indigenous Finnish fighter types. Also, one damaged bomber took up workshop space equalling three fighters.

Finland was required to expel or intern remaining German forces as part of its peace agreement with the Soviets in mid-1944. As a result, the final air battles were against retreating Luftwaffe units.

The Finnish Air Force did not bomb any civilian targets during either war.[9] Curiously, overflying Soviet towns and bases was also forbidden, as to avoid any unneeded provocations and to spare equipment.

The Finnish Air Force shot down 1,621 Soviet aircraft while losing 210 of its own aircraft during the Continuation War.[10]

After World War II

The end of World War II, and the Paris peace talks of 1947 brought with it some limitations to the FAF. Among these were that the Finnish Air Force were to have:

- No more than 60 combat aircraft

- No aircraft with internal bomb bays

- No guided missiles or atomic weapons

- No weaponry of German construction or using German parts

- A maximum strength of 3,000 persons

- No offensive weapons

These revisions followed Soviet demands closely. When Britain tried to add some of their own (fearing that the provisions were there only to augment the Soviet air-defences) they were opposed by the Soviets. The revisions were again revised in 1963 and Finland was allowed to buy guided missiles and a few bombers that were used as target-tugs. The FAF also used a loop-hole to strengthen its capabilities by purchasing large numbers of two-seater aircraft, which counted as trainer aircraft and were not included in the revisions. These aircraft could have secondary roles.[11]

During the Cold War years, Finland tried to balance its purchases between east, west and domestic producers. This led to a diverse inventory of Soviet, British, Swedish, French and Finnish aircraft. After leading Finnish politicians held unofficial talks with their Swedish counterparts, Sweden began storing surplus Saab 35 Drakens, which were to be transferred to Finland in the event of a war with the Soviet Union. These were kept until the 1980s.[12]

On 22 September 1990, a week before the unification of Germany, Finland declared that the limiting treaties were no longer active and that all the provisions of the Paris Peace Treaties were nullified.[13]

In the 1990s, with the Cold War over, the Finnish Air Force ended its policy of purchasing Soviet/Russian aircraft and replaced the Saab Draken and MiG-21s in its fighter wing with US F/A-18C/D Hornets.[14][15][16][17]

Today, the FAF is organized into three Air Commands, each assigned to one of the three air defence areas into which Finland is divided. The main Wing bases are at Rovaniemi, Tampere and Kuopio-Rissala, each with a front-line squadron. Pilot training is undertaken at the Air Force Academy in Tikkakoski, with advanced conversion performed at squadron level.

The HX Fighter Program

The current Hornet fleet is set to begin being phased out from 2025, and to be completely decommissioned by 2030.

The Finnish MoD initiated its Hornet replacement programme in June 2015, and named it the "HX Fighter Program".

A working group was created and it identified suitable aircraft.[18]

The final decision for choosing the new Air Force jet is based on five key considerations, which are the multi-role fighter’s military capability, security of supply, industrial cooperation solutions, procurement and life cycle costs, and security and defence policy implications. An extensive questionnaire had been sent out the producers asking what their products can offer Finland in form of capabilities, cost, security of supply and the domestic industry's role, as well as security and defence policy impacts.

The goal is to retain the numerical strength of the FAF fighter fleet, which means that the goal is to obtain some 64 aircraft. The MoD has estimated that the programme will cost somewhere between 7-10 billion Euros. In October 2019, the government of Finland stipulated a budget ceiling of €10 billion for the HX fighter programme.[19]

In December 2015 the Finnish MoD sent a letter to Britain, France, Sweden and the US informing them that the fighter project had been launched in the Defence Forces.

The request for information concerning the HX Fighter Program was sent in April 2016.[20] Responses were received from all five participants in November 2016. The official Request for Quotation was sent in the spring of 2018. The goal is to start the fighter candidates’ environmental testing in Finland in 2019.[21] The buying decision is scheduled to take place in 2021.[22]

Participants

- Boeing has offered its EA-18G Growler variant in its package.

Aircraft

Current inventory

.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

| Aircraft | Origin | Type | Variant | In service | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combat Aircraft | ||||||

| Boeing F/A-18 | United States | multirole | F/A-18C | 55[26] | ||

| Electronic Warfare | ||||||

| CASA C-295 | Spain | electronic warfare | C-295M | 1[27] | ||

| Transport | ||||||

| Learjet 35 | United States | transport | 35-A/S | 3[28] | ||

| CASA C-295 | Spain | transport | C-295M | 2[27] | ||

| Pilatus PC-12 | Switzerland | liaison | PC-12 NG | 6[29] | ||

| Trainer Aircraft | ||||||

| BAE Hawk | United Kingdom | jet trainer | 51 / 51A / 66 | 8 / 7 / 16[30] | ||

| L-70 Vinka | Finland | primary trainer | 26[31] | |||

| Grob G 115E | Germany | primary trainer | 28[32] | |||

| Boeing F/A-18 | United States | conversion trainer | F/A-18D | 7[26] | ||

Note: Three C-17 Globemaster III's are available through the Heavy Airlift Wing based in Hungary.[33]

Armament

| Name | Origin | Type | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air-to-air missile | ||||||

| AIM-120 AMRAAM | United States | beyond-visual-range missile | AIM-120A 445 units AIM-120B AIM-120C-5 9 units AIM-120C-7 300 units[34] | |||

| AIM-9 Sidewinder | United States | AIM-9M 480 units AIM-9X 150 units[34] | ||||

| Air-to-surface missile | ||||||

| AGM-154C JSOW | United States | joint standoff weapon | [34] | |||

| AGM-158A JASSM | United States | air-launched cruise missile | 70 units[34] | |||

| General-purpose bomb | ||||||

| GBU-31V1 JDAM | United States | 937 kg (2000 lb) precision guided munition | 114 units[34] | |||

| GBU-32 | United States | 454 kg (1000 lb) precision guided munition | [34] | |||

| GBU-38 | United States | 226 kg (500 lb) precision guided munition | [34] | |||

Organization

_of_the_Finnish_Air_Force_departs_RIAT_Fairford_17July2017_arp.jpg)

_of_the_Finnish_Air_Force_arrives_RIAT_Fairford_13July2017_arp.jpg)

The Air Force is organised into three air commands, each of which operates a fighter squadron. In addition, the Air Force includes a number of other units:

- Air Force General Staff, in Tikkakoski

- Air Force Command (AFCOMFIN), at Jyväskylä–Tikkakoski Air Base

- Air Operations Centre, at Jyväskylä–Tikkakoski Air Base

- Lapland Air Command, at Rovaniemi Air Base[35]

- Fighter Squadron 11 (Hävittäjälentolaivue 11, HävLLv 11)

- 1st Flight, with F-18C/D

- 2nd Flight, with F-18C/D

- Communication Flight, with L-70 Vinka, PC-12 NG

- 5th Sector Operations Center

- Base Support Squadron

- C4I Center

- Maintenance Center

- Fighter Squadron 11 (Hävittäjälentolaivue 11, HävLLv 11)

- Karelia Air Command, at Kuopio Air Base

- Fighter Squadron 31 (Hävittäjälentolaivue 31, HävLLv 31)

- Headquarters Flight

- 1st Fighter Flight, with F-18C/D

- 2nd Flight, with F-18C/D

- 3rd Flight, with F-18C/D

- Communication Flight, with L-70 Vinka, PC-12 NG

- 7th Sector Operations Center[36]

- Base Support Squadron

- C4I Center

- Maintenance Center

- Fighter Squadron 31 (Hävittäjälentolaivue 31, HävLLv 31)

- Satakunta Air Command, at Tampere-Pirkkala Air Base[37]

- Air Operations Support Squadron

- Headquarters Flight

- Flight, with CASA C-295M, Learjet 35A/S

- Base Support Squadron

- C4I Center

- Maintenance Center

- Air Operations Support Squadron

- Air Force Academy, at Jyväskylä–Tikkakoski Air Base[38]

- Fighter Squadron 41, with Hawk Mk 51/51A, 61

- Headquarters Flight

- 1st Flight, with Hawk Mk.51, Mk.51A, Mk.66

- 2nd Flight, with Hawk Mk.51, Mk.51A, Mk.66

- 3rd Flight, with Hawk Mk.51, Mk.51A, Mk.66

- Communication Flight, with L-70 Vinka, PC-12 NG

- Training Center, with Grob G 115E

- Training Battalion

- Air Force Reserve Officer School

- Air Force NCO School

- Signal Technology Company

- Air Traffic Engineer Company

- Base Support Squadron

- C4I Center

- Maintenance Center

- Air Force Band

- Fighter Squadron 41, with Hawk Mk 51/51A, 61

- Air Force Command (AFCOMFIN), at Jyväskylä–Tikkakoski Air Base

War Time Strength

- 2x F-18C squadrons

- 1x Hawk squadron

- 1x Air Operations Support squadron

- 4x Stand-by bases

- 4x Communication flights

Total strength is 38,000.

Commanders

| Rank | Name | From | To |

| Captain | Carl Seber | April 28, 1918 | December 13, 1918 |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Torsten Aminoff | December 14, 1918 | January 9, 1919 |

| Colonel | Sixtus Hjelmmann | January 10, 1919 | October 25, 1920 |

| Major | Arne Somersalo | October 26, 1920 | February 2, 1926 |

| Colonel | Väinö Vuori | February 2, 1926 | September 7, 1932 |

| Lieutenant General | Jarl Lundqvist | September 8, 1932 | June 29, 1945 |

| Lieutenant General | Frans Helminen | June 30, 1945 | November 30, 1952 |

| Lieutenant General | Reino Artola | December 1, 1952 | December 5, 1958 |

| Major General | Fjalar Seeve | December 6, 1958 | September 12, 1964 |

| Lieutenant General | Reino Turkki | September 13, 1964 | December 4, 1968 |

| Lieutenant General | Eero Salmela | February 7, 1969 | April 21, 1975 |

| Lieutenant General | Rauno Meriö | April 22, 1975 | January 31, 1987 |

| Lieutenant General | Pertti Jokinen | February 1, 1987 | January 31, 1991 |

| Lieutenant General | Heikki Nikunen | February 1, 1991 | April 30, 1995 |

| Major General | Matti Ahola | May 1, 1995 | August 31, 1998 |

| Lieutenant General | Jouni Pystynen | September 1, 1998 | December 31, 2004 |

| Lieutenant General | Heikki Lyytinen | January 1, 2005 | July 31, 2008 |

| Lieutenant General | Jarmo Lindberg | August 1, 2008 | February 29, 2012 |

| Major General | Lauri Puranen | March 1, 2012 | March 31, 2014 |

| Major General | Kim Jäämeri | April 1, 2014 | May 31, 2017 |

| Major General | Sampo Eskelinen | June 1, 2017 | April 1, 2019 |

| Major General | Pasi Jokinen | April 1, 2019 |

See also

References

- "Finnish Air Force today". Finnish Air Force. Archived from the original (Web article) on 2008-02-12. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Keskinen, Partonen, Stenman 2005.

- A photograph of this plane can be found in the book by Shores 1969, p. 4.

- Heinonen 1992.

- "Armistice Agreement". Heninen.net. Archived from the original on 2014-01-28. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- Claudia Allen (1 July 2020). "Finland's air force quietly drops swastika symbol". BBC News. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Finnish Air Force". Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- "Finnish Air Force History". Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- "Continuation War Aviation in Review". virtualpilots.fi. 2005-09-19. Archived from the original on 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- Kalevi Keskinen, Kari Stenman. Aerial Victories 1, Aerial Victories 2 (2006)

- Arter, David: Scandinavian politics today, Manchester University Press (1999), ISBN 0-7190-5133-9, p.254

- "Avslöjande: Sverige lagrade jaktplan för finska piloter" (in Swedish). Hbl.fi. Archived from the original on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- "NATO Review - No. 1 - Feb 1993". Archived from the original on 2016-09-17. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- Finland MiG-21 Archived 2017-02-22 at the Wayback Machine Aviata.net Retrieved February 22, 2017

- Jeziorski, Andrzej F-18 costs delay Finnish support requirements November 15, 1995 Archived February 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Flight Global Retrieved February 22, 2017

- F/A-18 Hornet Archived 2017-02-22 at the Wayback Machine Global Security Retrieved February 22, 2017

- The Finnish Air Force Archived 2017-02-22 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved February 22, 2017

- "Working group proposes multi-role fighters to replace F/A-18 aircraft" (press release). FI: Def Min. 11 June 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- "Hävittäjähankinnassa yllätyskäänne: Suomi saattaa ostaa nykyistä enemmän taistelukoneita - hallitus asetti hintakatoksi 10 miljardia euroa". Iltalehti (in Finnish). 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "Finland sends RFI to 4 countries for Hornet replacement". The Finland times. 23 April 2016.

- "Requests for Quotation for the HX Programme will be sent to all candidates" (press release). FI: Ministry of Defence. 24 April 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- "The Finnish Defence Forces' Logistics Command received responses concerning the replacement of the Hornet aircraft" (press release). FI: Ministry of Defence. 22 November 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- "Welcome to Eurofighter Typhoon". BAE Systems. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "Lockheed Martin. Your Mission is Ours". Lockheed Martin. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "Gripen E". Saab. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "Finnish Air Force Aircraft Fact Sheet: Boeing F/A-18C and F/A-18D Hornet" (PDF). Finnish Air Force. January 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Finnish Air Force Aircraft Fact Sheet: Airbus Military C295M" (PDF). Finnish Air Force. January 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Finnish Air Force Aircraft Fact Sheet: Gates Learjet 35A/S" (PDF). Finnish Air Force. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Finnish Air Force Aircraft Fact Sheet: Pilatus PC-12 NG" (PDF). Finnish Air Force. January 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Finnish Air Force Aircraft Fact Sheet: BAE Systems Hawk" (PDF). Finnish Air Force. December 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Finnish Air Force Aircraft Fact Sheet: Valmet L-70 Vinka" (PDF). Finnish Air Force. January 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Finnish Air Force Aircraft Fact Sheet: Grob G 115E" (PDF). Finnish Air Force. July 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "Heavy Airlift Wing". Strategic Airlift Capability Program. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Trade Registers Archived 2011-05-13 at the Wayback Machine. Armstrade.sipri.org. Retrieved on 2017-12-23.

- "Puolustusvoimat". Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- "Puolustusvoimat" (in Finnish). Ilmavoimat.fi. 2014-02-14. Archived from the original on 2007-04-25. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- Satakunnan lennoston organisaatio. Satakunta Air Command. Retrieved 2008-12-22. (in Finnish)

- "Puolustusvoimat" (in Finnish). Ilmavoimat.fi. 2014-02-14. Archived from the original on 2007-09-05. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- Shores, Christopher (1969). Finnish Air Force, 1918–1968. Reading, Berkshire, UK: Osprey Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0668021210.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Air force of Finland. |