Collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The interests of the employees are commonly presented by representatives of a trade union to which the employees belong. The collective agreements reached by these negotiations usually set out wage scales, working hours, training, health and safety, overtime, grievance mechanisms, and rights to participate in workplace or company affairs.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labour |

|---|

|

|

Labour movement

|

|

Academic disciplines |

The union may negotiate with a single employer (who is typically representing a company's shareholders) or may negotiate with a group of businesses, depending on the country, to reach an industry-wide agreement. A collective agreement functions as a labour contract between an employer and one or more unions. Collective bargaining consists of the process of negotiation between representatives of a union and employers (generally represented by management, or, in some countries such as Austria, Sweden and the Netherlands, by an employers' organization) in respect of the terms and conditions of employment of employees, such as wages, hours of work, working conditions, grievance procedures, and about the rights and responsibilities of trade unions. The parties often refer to the result of the negotiation as a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) or as a collective employment agreement (CEA).

History

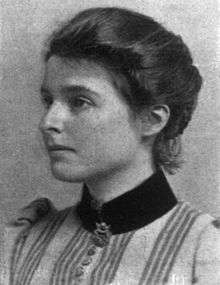

The term "collective bargaining" was first used in 1891 by Beatrice Webb, a founder of the field of industrial relations in Britain.[2] It refers to the sort of collective negotiations and agreements that had existed since the rise of trade unions during the 18th century.

United States

In the United States, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 made it illegal for any employer to deny union rights to an employee. The issue of unionizing government employees in a public-sector trade union was much more controversial until the 1950s. In 1962 President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order granting federal employees the right to unionize.

An issue of jurisdiction surfaced in National Labor Relations Board v. Catholic Bishop of Chicago (1979) when the Supreme Court held that the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) could not assert jurisdiction over a church-operated school because such jurisdiction would violate the First Amendment establishment of freedom of religion and the separation of church of state.[3]

International protection

Ronald Reagan, Labor Day Speech at Liberty State Park, 1980

The right to collectively bargain is recognized through international human rights conventions. Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights identifies the ability to organize trade unions as a fundamental human right.[5] Item 2(a) of the International Labour Organization's Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work defines the "freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining" as an essential right of workers.[6] The Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (C087) and several other conventions specifically protect collective bargaining through the creation of international labour standards that discourage countries from violating workers' rights to associate and collectively bargain.[7]

In June 2007 the Supreme Court of Canada extensively reviewed the rationale for regarding collective bargaining as a human right. In the case of Facilities Subsector Bargaining Association v. British Columbia, the Court made the following observations:

The right to bargain collectively with an employer enhances the human dignity, liberty and autonomy of workers by giving them the opportunity to influence the establishment of workplace rules and thereby gain some control over a major aspect of their lives, namely their work… Collective bargaining is not simply an instrument for pursuing external ends…rather [it] is intrinsically valuable as an experience in self-government… Collective bargaining permits workers to achieve a form of workplace democracy and to ensure the rule of law in the workplace. Workers gain a voice to influence the establishment of rules that control a major aspect of their lives.[8]

Empirical findings

- Union members and other workers covered by collective agreements get, on average, a wage markup over their nonunionized (or uncovered) counterparts. Such a markup is typically 5 to 10 percent in industrial countries.[9]

- Unions tend to equalize the income distribution, especially between skilled and unskilled workers.[9]

- The welfare loss associated with unions is 0.2 to 0.5 percent of GDP, which is similar to monopolies in product markets.[9]

Sweden

In Sweden the coverage of collective agreements is very high despite the absence of legal mechanisms to extend agreements to whole industries. In 2018, 83% of all private sector employees were covered by collective agreements, 100% of public sector employees and in all 90% (referring to the whole labor market).[10] This reflects the dominance of self-regulation (regulation by the labour market parties themselves) over state regulation in Swedish industrial relations.[11]

United States

In the United States, the National Labor Relations Act (1935) covers most collective agreements in the private sector. This act makes it illegal for employers to discriminate, spy on, harass, or terminate the employment of workers because of their union membership or to retaliate against them for engaging in organizing campaigns or other "concerted activities", to form company unions, or to refuse to engage in collective bargaining with the union that represents their employees. It is also illegal to require any employee to join a union as a condition of employment.[12] Unions are also able to secure safe work conditions and equitable pay for their labor.

At a workplace where a majority of workers have voted for union representation, a committee of employees and union representatives negotiate a contract with the management regarding wages, hours, benefits, and other terms and conditions of employment, such as protection from termination of employment without just cause. Individual negotiation is prohibited. Once the workers' committee and management have agreed on a contract, it is then put to a vote of all workers at the workplace. If approved, the contract is usually in force for a fixed term of years, and when that term is up, it is then renegotiated between employees and management. Sometimes there are disputes over the union contract; this particularly occurs in cases of workers fired without just cause in a union workplace. These then go to arbitration, which is similar to an informal court hearing; a neutral arbitrator then rules whether the termination or other contract breach is extant, and if it is, orders that it be corrected.

In 24 U.S. states,[13] employees who are working in a unionized shop may be required to contribute towards the cost of representation (such as at disciplinary hearings) if their fellow employees have negotiated a union security clause in their contract with management. Dues are generally 1–2% of pay. However, union members and other workers covered by collective agreements get, on average, a 5-10% wage markup over their nonunionized (or uncovered) counterparts.[9] Some states, especially in the south-central and south-eastern regions of the U.S., have outlawed union security clauses; this can cause controversy, as it allows some net beneficiaries of the union contract to avoid paying their portion of the costs of contract negotiation. Regardless of state, the Supreme Court has held that the Act prevents a person's union dues from being used without consent to fund political causes that may be opposed to the individual's personal politics. Instead, in states where union security clauses are permitted, such dissenters may elect to pay only the proportion of dues which go directly toward representation of workers.[14]

The American Federation of Labor was formed in 1886, providing unprecedented bargaining powers for a variety of workers.[15] The Railway Labor Act (1926) required employers to bargain collectively with unions.

In 1931, the Supreme Court, in the case of Texas & N.O.R. Co. v. Brotherhood of Railway Clerks, upheld the act's prohibition of employer interference in the selection of bargaining representatives.[15] In 1962, President Kennedy signed an executive order giving public-employee unions the right to collectively bargain with federal government agencies.[15]

The Office of Labor-Management Standards, part of the United States Department of Labor, is required to collect all collective bargaining agreements covering 1,000 or more workers, excluding those involving railroads and airlines.[16] They provide public access to these collections through their website.

OECD

Only one in three OECD employees have wages which were agreed on through collective bargaining. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, with its 36 members, has become an outspoken proponent for collective bargaining as a way to ensure that the falling unemployment also leads to higher wages.[17]

See also

- 11 U.S.C. § 1113 – Rejection of Collective Bargaining Agreements

- Boulwarism

- Canadian labour law

- Enterprise bargaining agreement

- Labour law

- Labour economics

- UK labour law

- US labor law

- Right-to-work law

- Surface bargaining

- Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949

- 2011 Wisconsin protests, related to attempts to reduce or eliminate collective bargaining rights for public employee unions in Wisconsin

- 2011 United States public employee protests

- Civic Openness In Negotiations

- Project Labor Agreement

Notes

- "BLS Information". Glossary. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Information Services. February 28, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- Adrian Wilkinson et al. eds. (2014). Handbook of Research on Employee Voice. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 227. ISBN 9780857939272.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Pynes, J.E. & Lombardi (2011) Human Resources Management for Healthcare Organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

- http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/reference/9.1.80.html

- United Nations General Assembly (1948). "Article 23". Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Paris. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- International Labour Organization (1998). Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. 86th Session: Geneva. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- "C087 - Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87)". International Labour Organization. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Health Services and Support – Facilities Subsector Bargaining Assn. v. British Columbia [2007] SCC 27 Archived July 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- Toke Aidt and Zafiris Tzannatos (2002). "Unions and Collective Bargaining".

- Anders Kjellberg (2020) Kollektivavtalens täckningsgrad samt organisationsgraden hos arbetsgivarförbund och fackförbund, Department of Sociology, Lund University. Studies in Social Policy, Industrial Relations, Working Life and Mobility. Research Reports 2020:1, Appendix 3 (in English) Table F

- Anders Kjellberg (2017) ”Self-regulation versus State Regulation in Swedish Industrial Relations” In Mia Rönnmar and Jenny Julén Votinius (eds.) Festskrift till Ann Numhauser-Henning. Lund: Juristförlaget i Lund 2017, pp. 357-383 357-383ning. Lund: Juristförlaget i Lund 2017, pp. 357-383

- "Can I be required to be a union member or pay dues to a union?". National Right To Work. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- "National Right to Work Foundation » Right to Work States". www.nrtw.org.

- "Communications Workers of America v. Beck". Retrieved 2011-08-27., 487 U.S. 735.

- Illinois Labor History Society. A Curriculum of United States Labor History for Teachers Archived 2008-05-14 at the Wayback Machine. Online at the Illinois Labor History Society Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on August 29, 2007.

- "Collective Bargaining Agreements File: Online Listings of Private and Public Sector Agreements". Office of Labor-Management Standards (OLMS). Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- lars. "OECD: The crisis is over, but collective bargaining is needed for wage growth — Nordic Labour Journal". www.nordiclabourjournal.org.

References

- Buidens, Wayne, and others. "Collective Gaining: A Bargaining Alternative." Phi Delta Kappan 63 (1981): 244-245.

- DeGennaro, William, and Kay Michelfeld. "Joint Committees Take the Rancor out of Bargaining with Our Teachers." The American School Board Journal 173 (1986): 38-39.

- Herman, Jerry J. "With Collaborative Bargaining, You Work with the Union--Not Against It." The American School Board Journal 172 (1985): 41-42, 47.

- Huber, Joe; and Jay Hennies. "Fix on These Five Guiding Lights, and Emerge from the Bargaining Fog." The American School Board Journal 174 (1987): 31.

- Kjellberg, Anders (2019) "Sweden: collective bargaining under the industry norm", in Torsten Müller & Kurt Vandaele & Jeremy Waddington (eds.) Collective bargaining in Europe: towards an endgame, European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) Brussels 2019. Vol. III (pp. 583-604).

- Liontos, Demetri. Collaborative Bargaining: Case Studies and Recommendations. Eugene: Oregon School Study Council, University of Oregon, September 1987. OSSC Bulletin Series. 27 pages. ED number not yet assigned.

- McMahon, Dennis O. "Getting to Yes." Paper presented at the annual conference of the American Association of School Administrators, New Orleans, LA, February 20–23, 1987. ED 280 188.

- Namit, Chuck; and Larry Swift. "Prescription for Labor Pains: Combine Bargaining with Problem Solving." The American School Board Journal 174 (1987): 24.

- Nyland, Larry. "Win/Win Bargaining Takes Perseverance." The Executive Educator 9 (1987): 24.

- O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003) [January 2002]. Economics: Principles in Action. The Wall Street Journal: Classroom Edition (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall: Addison Wesley Longman. p. 223. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Smith, Patricia; and Russell Baker. "An Alternative Form of Collective Bargaining." Phi Delta Kappan 67 (1986): 605-607.

- Alberta Human Rights Act, RSA 2000, c A-25

- Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- Donnelly, Jack. "Cultural and Universal Human Right". Human Right Quarterly 6(1984): 400-419

- Dunmore v. Ontario (Attorney General), [2001] 3 S.C.R. 1016, 2001 SCC 94

- Health Services and Support—Facilities Subcontractor Bargaining Assn. v. British Columbia, [2007] SCC 27, [2007] 2 S.C.R. 391

- Mathiesen, Kay. "labor laws on unionization and collective bargaining — comparative study". Journal of information Ethics. 3(2009):245-567. Print.

- Sitati, Ezekiel. "Examining the development sin the labor laws". Melbournes Journal of politic 3(2009):55-74. Print

- Ontario (Attorney General) v. Fraser, 2011 SCC 20

- Reference Re Public Service Employee Relations Act (Alberta), [1987] 1 S.C.R. 313

External links

- Labor & Worklife Program at Harvard Law school

- Collective Bargaining Subject Guide at the ILR School, Cornell University

- Collective Bargaining, Labor Law, and Labor History at DigitalCommons@ILR

- Collective Bargaining Agreements at DigitalCommons@ILR

- GVSU links to actual arbitration awards and collective bargaining resources