First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres (French: Première Bataille des Flandres German: Erste Flandernschlacht, 19 October – 22 November 1914) was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the First Battle of Flanders, in which German, French, Belgian armies and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) fought from Arras in France to Nieuport on the Belgian coast, from 10 October to mid-November. The battles at Ypres began at the end of the Race to the Sea, reciprocal attempts by the German and Franco-British armies to advance past the northern flank of their opponents. North of Ypres, the fighting continued in the Battle of the Yser (16–31 October), between the German 4th Army, the Belgian army and French marines.

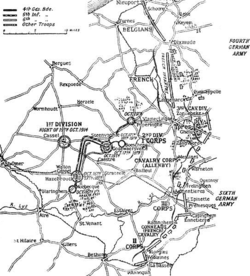

The fighting has been divided into five stages, an encounter battle from 19 to 21 October, the Battle of Langemarck from 21 to 24 October, the battles at La Bassée and Armentières to 2 November, coincident with more Allied attacks at Ypres and the Battle of Gheluvelt (29–31 October), a fourth phase with the last big German offensive, which culminated at the Battle of Nonne Bosschen on 11 November, then local operations which faded out in late November. Brigadier-General James Edmonds, the British official historian, wrote in the History of the Great War, that the II Corps battle at La Bassée could be taken as separate but that the battles from Armentières to Messines and Ypres, were better understood as one battle in two parts, an offensive by III Corps and the Cavalry Corps from 12 to 18 October against which the Germans retired and an offensive by the German 6th Army and 4th Army from 19 October to 2 November, which from 30 October, took place mainly north of the Lys, when the battles of Armentières and Messines merged with the Battles of Ypres.[lower-alpha 1]

Attacks by the BEF (Field Marshal Sir John French) the Belgians and the French Eighth Army in Belgium made little progress beyond Ypres. The German 4th and 6th Armies took small amounts of ground at great cost to both sides, during the Battle of the Yser and further south at Ypres. General Erich von Falkenhayn, head of the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, German General Staff), then tried a limited offensive to capture Ypres and Mont Kemmel, from 19 October to 22 November. Neither side had moved forces to Flanders fast enough to obtain a decisive victory and by November both sides were exhausted. The armies were short of ammunition, suffering from low morale and some infantry units refused orders. The autumn battles in Flanders had become static, attrition operations, unlike the battles of manoeuvre in the summer. French, British and Belgian troops in improvised field defences, repulsed German attacks for four weeks. From 21 to 23 October, German reservists had made mass attacks at Langemarck, with losses of up to 70 percent, to little effect.

Warfare between mass armies, equipped with the weapons of the Industrial Revolution and its later developments, proved to be indecisive, because field fortifications neutralised many classes of offensive weapon. The defensive firepower of artillery and machine guns, dominated the battlefield and the ability of the armies to supply themselves and replace casualties prolonged battles for weeks. Thirty-four German divisions fought in the Flanders battles, against twelve French, nine British and six Belgian divisions, along with marines and dismounted cavalry. Over the winter, Falkenhayn reconsidered Germany strategy because Vernichtungsstrategie and the imposition of a dictated peace on France and Russia had exceeded German resources. Falkenhayn devised a new strategy to detach either Russia or France from the Allied coalition through diplomacy as well as military action. A strategy of attrition (Ermattungsstrategie) would make the cost of the war too great for the Allies, until one dropped out and made a separate peace. The remaining belligerents would have to negotiate or face the Germans concentrated on the remaining front, which would be sufficient for Germany to inflict a decisive defeat.

Background

Strategic developments

Eastern Front

On 9 October, the First German offensive against Warsaw began with the battles of Warsaw (9–19 October) and Ivangorod (9–20 October). Four days later, Przemyśl was relieved by the advancing Austro-Hungarians and the Battle of Chyrow 13 October – 2 November) began in Galicia. Czernowitz in Bukovina was re-occupied by the Austro-Hungarian army on 22 August and then lost again to the Russian army on 28 October. On 29 October, the Ottoman Empire commenced hostilities against Russia, when Turkish warships bombarded Odessa, Sevastopol and Theodosia. Next day Stanislau in Galicia was taken by Russian forces and the Serbian army began a retreat from the line of the Drina. On 4 November, the Russian army crossed the frontier of Turkey-in-Asia and seized Azap.[1]

Britain and France declared war on Turkey on 5 November and next day, Keupri-Keni in Armenia was captured, during the Bergmann Offensive (2–16 November) by the Russian army. On 10 October, Przemysl was surrounded again by the Russian army, beginning the Second Siege; Memel in East Prussia was occupied by the Russians a day later. Keupri-Keni was recaptured by the Ottoman army on 14 November, the Sultan proclaimed Jihad, next day the Battle of Cracow (15 November – 2 December) began and the Second Russian Invasion of North Hungary (15 November – 12 December) commenced. The Second German Offensive against Warsaw opened with the Battle of Łódź (16 November – 15 December).[2]

Great Retreat

The Great Retreat was a long withdrawal by the Franco-British armies to the Marne, from 24 August – 28 September 1914, after the success of the German armies in the Battle of the Frontiers (7 August – 13 September). After the defeat of the French Fifth Army at the Battle of Charleroi (21 August) and the BEF in the Battle of Mons (23 August), both armies made a rapid retreat to avoid envelopment.[lower-alpha 2] A counter-offensive by the French and the BEF at the First Battle of Guise (29–30 August), failed to end the German advance and the Franco-British retreat continued beyond the Marne. From 5–12 September, the First Battle of the Marne ended the retreat and forced the German armies to retire towards the Aisne river, where the First Battle of the Aisne was fought from 13–28 September.[3]

Tactical developments

Flanders

After the retreat of the French Fifth Army and the BEF, local operations took place from August–October. General Fournier was ordered on 25 August to defend the fortress at Maubeuge, which was surrounded two days later by the German VII Reserve Corps. Maubeuge was defended by fourteen forts, a garrison of 30,000 French territorials and c. 10,000 French, British and Belgian stragglers. The fortress blocked the main Cologne–Paris rail line, leaving only the line from Trier to Liège, Brussels, Valenciennes and Cambrai open to the Germans, which was needed to carry supplies southward to the armies on the Aisne and transport troops of the 6th Army northwards from Lorraine to Flanders.[4] On 7 September, the garrison surrendered, after super-heavy artillery from the Siege of Namur demolished the forts. The Germans took 32,692 prisoners and captured 450 guns.[5][4] Small detachments of the Belgian, French and British armies conducted operations in Belgium and northern France, against German cavalry and Jäger.[6]

On 27 August, a squadron of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) flew to Ostend, for reconnaissance sorties between Bruges, Ghent and Ypres.[7] Royal Marines landed at Dunkirk on the night of 19/20 September and on 28 September, a battalion occupied Lille. The rest of the brigade occupied Cassel on 30 September and scouted the country in motor cars; an RNAS Armoured Car Section was created, by fitting vehicles with bullet-proof steel.[8][9] On 2 October, the Marine Brigade was sent to Antwerp, followed by the rest of the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division on 6 October, having landed at Dunkirk on the night of 4/5 October. From 6–7 October, the 7th Division and the 3rd Cavalry Division landed at Zeebrugge.[10] Naval forces collected at Dover were formed into a separate unit, which became the Dover Patrol, to operate in the Channel and off the French-Belgian coast.[11]

BEF

In late September, Marshal Joseph Joffre and Field Marshal John French discussed the transfer of the BEF from the Aisne to Flanders, to unify British forces on the Continent, shorten the British lines of communication from England and to defend Antwerp and the Channel Ports. Despite the inconvenience of British troops crossing French lines of communication, when French forces were moving north after the Battle of the Aisne, Joffre agreed subject to a proviso, that French would make individual British units available for operations as soon as they arrived. On the night of 1/2 October, the transfer of the BEF from the Aisne front began in great secrecy. Marches were made at night and billeted troops were forbidden to venture outside in daylight. On 3 October, a German wireless message was intercepted, which showed that the BEF was still believed to be on the Aisne.[12]

II Corps moved from the night of 3/4 October and III Corps followed from 6 October, leaving a brigade behind with I Corps, which stayed until the night of 13/14 October. II Corps arrived around Abbeville from 8–9 October and concentrated to the north-east around Gennes-Ivergny, Gueschart, Le Boisle and Raye, preparatory to an advance on Béthune. The 2nd Cavalry Division arrived at St Pol and Hesdin on 9 October and the 1st Cavalry Division arrived a day later. GHQ left Fère-en-Tardenois and arrived at Saint-Omer on 13 October. III Corps began to assemble around Saint-Omer and Hazebrouck on 11 October, then moved behind the left flank of II Corps, to advance on Bailleul and Armentières. I Corps arrived at Hazebrouck on 19 October and moved eastwards to Ypres.[13]

Race to the Sea

After a tour of the front on 15 September, the new chief of the German General Staff (Oberste Heeresleitung, OHL), General Erich von Falkenhayn planned to continue the withdrawal of the right flank of the German armies in France from the Aisne, to gain time for a strategic regrouping, by moving the 6th Army from Lorraine. A decisive result (Schlachtentscheidung), was intended to come from the offensive of the 6th Army but on 18 September, French attacks endangered the German northern flank instead and the 6th Army used the first units from Lorraine to repulse the French as a preliminary.[14][lower-alpha 3] The French used undamaged rail and communications networks, to move troops faster than the Germans but neither side could begin a decisive attack, having to send units forward piecemeal, against reciprocal attacks of the opponent, in the Race to the Sea (The name is a misnomer, because neither side raced to the sea but tried to outflank their opponent before they reached it and ran out of room.)[21]

A German attack on 24 September, forced the French onto the defensive and Joffre reinforced the northern flank of the Second Army. As BEF units arrived, operations began piecemeal on the northern flank; the Belgian army refused a request by Joffre to leave the National redoubt of Belgium and sortie against German communications. A Franco-British offensive was substituted towards Lille and Antwerp. The allied troops managed to advance towards Lille and the Lys river but were stopped by German attacks in the opposite direction on 20 October.[23] The "race" ended on the Belgian coast around 17 October, when the last open area from Dixmude to the North Sea, was occupied by Belgian troops withdrawing from Antwerp after the Siege of Antwerp (28 September – 10 October). The outflanking attempts resulted in indecisive encounter battles through Artois and Flanders, at the Battle of La Bassée (10 October – 2 November), the Battle of Messines (12 October – 2 November) and the Battle of Armentières (13 October – 2 November).[24][25][lower-alpha 4]

Prelude

Terrain

North-east France and the south-west Belgium are known as Flanders. West of a line between Arras and Calais in the north-west are chalk downlands, covered with soil sufficient for arable farming. East of the line, the land declines in a series of spurs into the Flanders plain, bounded by canals linking Douai, Béthune, St Omer and Calais. To the south-east, canals run between Lens, Lille, Roubaix and Courtrai, the Lys river from Courtrai to Ghent and to the north-west lies the sea. The plain is almost flat, apart from a line of low hills from Cassel, eastwards to Mont des Cats, Mont Noir, Mont Rouge, Scherpenberg and Mount Kemmel. From Kemmel, a low ridge lies to the north-east, declining in elevation past Ypres through Wytschaete, Gheluvelt and Passchendaele, curving north then north-west to Dixmude where it merges with the plain. A coastal strip is about 10 mi (16 km) wide, near sea level and fringed by sand dunes. Inland the ground is mainly meadow, cut by canals, dykes, drainage ditches and roads built up on causeways. The Lys, Yser and upper Scheldt are canalised and between them the water level underground is close to the surface, rises further in the autumn and fills any dip, the sides of which then collapse. The ground surface quickly turns to a consistency of cream cheese and on the coast movement is confined to roads, except during frosts.[28]

In the rest of the Flanders Plain were woods and small fields, divided by hedgerows planted with trees and fields cultivated from small villages and farms. The terrain was difficult for infantry operations because of the lack of observation, impossible for mounted action because of the many obstructions and awkward for artillery because of the limited view. South of La Bassée Canal around Lens and Béthune was a coal-mining district full of slag heaps, pit-heads (fosses) and miners' houses (corons). North of the canal, the city of Lille, Tourcoing and Roubaix formed a manufacturing complex, with outlying industries at Armentières, Comines, Halluin and Menin, along the Lys river, with isolated sugar beet and alcohol refineries and a steel works near Aire-sur-la-Lys. Intervening areas were agricultural, with wide roads, which in France were built on shallow foundations or were unpaved mud tracks. Narrow pavé roads ran along the frontier and inside Belgium. In France, the roads were closed by the local authorities during thaws to preserve the surface and marked by Barrières fermėes signs, which were ignored by British lorry drivers. The difficulty of movement after the end of summer absorbed much of the labour available on road maintenance, leaving field defences to be built by front-line soldiers.[29]

Tactics

In October, Herbert Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War, forecast a long war and placed orders for the manufacture of a large number of field, medium and heavy guns and howitzers, sufficient to equip a 24-division army. The order was soon increased by the War Office but the rate of shell manufacture had an immediate effect on operations. While the BEF was still on the Aisne front, ammunition production for field guns and howitzers was 10,000 shells a month and only 100 shells per month were being manufactured for 60-pounder guns; the War Office sent another 101 heavy guns to France during October. As the contending armies moved north into Flanders, the flat terrain and obstructed view, caused by the number of buildings, industrial concerns, tree foliage and field boundaries, forced changes in British artillery methods. Lack of observation was remedied in part by decentralising artillery to infantry brigades and by locating the guns in the front line but this made them more vulnerable and several batteries were overrun in the fighting between Arras and Ypres. Devolving control of the guns made concentrated artillery-fire difficult to arrange, because of a lack of field telephones and the obscuring of signal flags by mists and fog.[30]

Co-operation with French forces to share the British heavy artillery was implemented and discussions with French gunners led to a synthesis of the French practice of firing a field artillery rafale (squall) before infantry moved to the attack and then ceasing fire, with the British preference for direct fire at observed targets, which was the beginning of the development of creeping barrages. During the advance of the III Corps and an attack on Méteren, the 4th Division issued divisional artillery orders, which stressed the concentration of the fire of the artillery, although during the battle the gunners fired on targets of opportunity, since German positions were so well camouflaged. As the fighting moved north into Belgian Flanders, the artillery found that Shrapnel shells had little effect on buildings and called for high explosive ammunition. During a general attack on 18 October, the German defenders achieved a defensive success, due to the disorganised nature of the British attacks, which only succeeded where close artillery support was available. The unexpected strength of the German 4th Army opposite, compounded British failings, although the partly trained, poorly led and badly equipped German reserve corps suffered high casualties.[31]

German tactics developed during the battles around Ypres, with cavalry still effective during the early maneuvering, although just as hampered by hedges and fenced fields, railway lines and urban growth as the Allied cavalry, which made the ground far better suited to defensive battle. German accounts stress the accuracy of Allied sniper fire, which led troops to remove the spike from Pickelhaube helmets and for officers to carry rifles to be less conspicuous. Artillery remained the main infantry-killer, particularly French 75 mm field guns, firing shrapnel at ranges lower than 1,000 yd (910 m). Artillery in German reserve units was far less efficient due to lack of training and fire often fell short.[32] In the lower ground between Ypres and the higher ground to the south-east and east, the ground was drained by many streams and ditches, divided into small fields with high hedges and ditches, roads were unpaved and the area was dotted with houses and farmsteads. Observation was limited by trees and open spaces could be commanded from covered positions and made untenable by small-arms and artillery fire. As winter approached the views became more open as woods and copses were cut down by artillery bombardments and the ground became much softer, particularly in the lower-lying areas.[33]

Plans

The French, Belgian and British forces in Flanders had no organisation for unified command but General Foch had been appointed commandant le groupe des Armées du Nord on 4 October by Joffre. The Belgian army managed to save 80,000 men from Antwerp and retire to the Yser and although not formally in command of British and Belgian forces, Foch obtained co-operation from both contingents.[22] On 10 October, Foch and French agreed to combine French, British and Belgian forces north and east of Lille, from the Lys to the Scheldt.[34] Foch planned a joint advance from Ypres to Nieuport, towards a line from Roulers, Thourout and Ghistelles, just south of Ostend. Foch intended to isolate the German III Reserve Corps, which was advancing from Antwerp, from the main German force in Flanders. French and Belgian forces were to push the Germans back against the sea, as French and British forces turned south-east and closed up to the Lys river from Menin to Ghent, to cross the river and attack the northern flank of the German armies.[35]

Falkenhayn sent the 4th Army headquarters to Flanders, to take over the III Reserve Corps and its heavy artillery, twenty batteries of heavy field howitzers, twelve batteries of 210 mm howitzers and six batteries of 100mm guns, after the Siege of Antwerp (28 September – 10 October). The XXII, XXIII, XXVI and XXVII Reserve corps, of the six new reserve corps formed from volunteers after the outbreak of the war, were ordered from Germany to join the III Reserve Corps on 8 October. The German reserve corps infantry were poorly trained and ill-equipped but on 10 October, Falkenhayn issued a directive that the 4th Army was to cross the Yser, advance regardless of losses and isolate Dunkirk and Calais, then turn south towards Saint-Omer. With the 6th Army to the south, which was to deny the Allies an opportunity to establish a secure front and transfer troops to the north, the 4th Army was to inflict an annihilating blow on the French, Belgian and BEF forces in French and Belgian Flanders.[36]

Battle of the Yser

French, British and Belgian troops covered the Belgian and British withdrawal from Antwerp towards Ypres and the Yser from Dixmude to Nieuport, on a 35 km (22 mi) front. The new German 4th Army was ordered to capture Dunkirk and Calais, by attacking from the coast to the junction with the 6th Army.[36] German attacks began on 18 October, coincident with the battles around Ypres and gained a foothold over the Yser at Tervaete. The French 42nd Division at Nieuport detached a brigade to reinforce the Belgians and German heavy artillery was countered on the coast, by Allied ships under British command, which bombarded German artillery positions and forced the Germans to attack further inland.[37] On 24 October, the Germans attacked fifteen times and managed to cross the Yser on a 5 km (3.1 mi) front. The French sent the rest of the 42nd Division to the centre but on 26 October, the Belgian Commander Félix Wielemans, ordered the Belgian army to retreat, until over-ruled by the Belgian king. Next day sluice gates on the coast at Nieuport were opened, which flooded the area between the Yser and the railway embankment, running north from Dixmude. On 30 October, German troops crossed the embankment at Ramscapelle but as the waters rose, were forced back the following evening. The floods reduced the fighting to local operations, which diminished until the end of the battle on 30 November.[38]

Battle

Battle of Langemarck

The Battle of Langemarck took place from 21–24 October, after an advance by the German 4th and 6th armies which began on 19 October, as the left flank of the BEF began advancing towards Menin and Roulers. On 20 October, Langemarck, north-east of Ypres, was held by a French territorial unit and the British IV corps to the south. I Corps (Lieutenant-General Douglas Haig) was due to arrive with orders to attack on 21 October. On 21 October, it had been cloudy and attempts to reconnoitre the German positions during the afternoon had not observed any German troops movements; the arrival of four new German reserve corps was discovered by prisoner statements, wireless interception and the increasing power of German attacks; 5 1⁄2 infantry corps were now known to be north of the Lys, along with the four cavalry corps, against 7 1⁄3 British divisions and five allied cavalry divisions. The British attack made early progress but the 4th army began a series of attacks, albeit badly organised and poorly supported. The German 6th and 4th armies attacked from Armentières to Messines and Langemarck. The British IV Corps was attacked around Langemarck, where the 7th Division was able to repulse German attacks and I Corps was able to make a short advance.[39]

Further north, French cavalry was pushed back to the Yser by the XXIII Reserve Corps and by nightfall was dug in from the junction with the British at Steenstraat to the vicinity of Dixmude, the boundary with the Belgian army.[39] The British closed the gap with a small number of reinforcements and on 23 October, the French IX Corps took over the north end of the Ypres salient, relieving I Corps with the 17th Division. Kortekeer Cabaret was recaptured by the 1st Division and the 2nd Division was relieved. Next day, I Corps had been relieved and the 7th Division lost Polygon Wood temporarily. The left flank of the 7th Division was taken over by the 2nd Division, which joined in the counter-attack of the French IX Corps on the northern flank towards Roulers and Thourout, as the fighting further north on the Yser impeded German attacks around Ypres.[40] German attacks were made on the right flank of the 7th Division at Gheluvelt.[41] The British sent the remains of I Corps to reinforce IV Corps. German attacks from 25–26 October were made further south, against the 7th Division on the Menin Road and on 26 October part of the line crumbled until reserves were scraped up to block the gap and avoid a rout.[42]

Battle of Gheluvelt

On 28 October, as the 4th Army attacks bogged down, Falkenhayn responded to the costly failures of the 4th and 6th armies by ordering the armies to conduct holding attacks while a new force, Armeegruppe Fabeck (General Max von Fabeck) was assembled from XV Corps and the II Bavarian Corps, the 26th Division and the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division, under the XIII Corps headquarters.[lower-alpha 5] The Armeegruppe was rushed up to Deûlémont and Werviq, the boundary between the 6th and 4th armies, to attack towards Ypres and Poperinghe. Strict economies were imposed on the 6th Army formations further south, to provide artillery ammunition for 250 heavy guns allotted to support an attack to the north-west, between Gheluvelt and Messines. The XV Corps was to attack on the right flank, south of the Menin–Ypres road to the Comines–Ypres canal and the main effort was to come from there to Garde Dieu by the II Bavarian Corps, flanked by the 26th Division.[43]

On 29 October, attacks by the XXVII Reserve Corps began against I Corps north of the Menin Road, at dawn, in thick fog. By nightfall, the Gheluvelt crossroads had been lost and 600 British prisoners taken. French attacks further north, by the 17th Division, 18th Division and 31st Division recaptured Bixschoote and Kortekeer Cabaret. Advances by Armeegruppe Fabeck to the south-west against I Corps and the dismounted Cavalry Corps further south, came to within 1.9 mi (3 km) of Ypres along the Menin road and brought the town into range of German artillery.[44] On 30 October, German attacks by the 54th Reserve Division and the 30th Division, on the left flank of the BEF at Gheluvelt, were repulsed but the British were pushed out of Zandvoorde, Hollebeke and Hollebeke Château as German attacks on a line from Messines to Wytschaete and St Yves were repulsed. The British rallied opposite Zandvoorde with French reinforcements and "Bulfin's Force" a command improvised for the motley of troops. The BEF had many casualties and used all its reserves but the French IX Corps sent its last three battalions and retrieved the situation in the I Corps sector. On 31 October, German attacks near Gheluvelt broke through until a counter-attack by the 2nd Worcestershire restored the situation.[45]

Battle of Nonne Bosschen

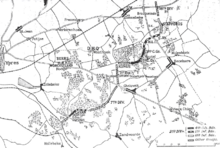

The French XVI Corps reached the area from St Eloi to Wytschaete on 1 November, to reinforce the cavalry Corps and the IX Corps attacked further north near Becelaere, which relieved the German pressure on both flanks of I Corps. By 3 November, Armeegruppe Fabeck had lost 17,250 men in five days and of 84 infantry battalions in the BEF which had come to France with about 1,000 officers and men each, 75 had fewer than 300 men, of which 18 battalions were under 100 men strong, despite receiving replacements up to 28 October. Foch planned an offensive towards Messines and Langemarck for 6 November, to expand the salient around Ypres. The attack was forestalled by German attacks on the flanks from 5–9 November. On 9 November, the Germans attacked the French and Belgians between Langemarck and Dixmude, forcing them back to the Yser, where the Belgians blew the crossings. After a lull, the German attacks resumed in great force from 10–11 November, mainly on the 4th Army front from Langemarck to Dixmude. On 10 November, 12 1⁄2 German divisions of the 4th and 6th Armies, Armeegruppe Fabeck and XXVII Reserve Corps attacked from Nonne Bosschen (Nun's Copse) and the edge of Polygon Wood, to Gheluvelt and across the Menin Road to Shrewsbury Forest in the south.[46]

On 11 November, the Germans attacked from Messines to Herenthage, Veldhoek woods, Nonne Bosschen and Polygon Wood. Massed small-arms fire repulsed German attacks between Polygon Wood and Veldhoek. The German 3rd Division and 26th Division broke through to St Eloi and advanced to Zwarteleen, some 3,000 yd (2,700 m) east of Ypres, where they were checked by the British 7th Cavalry Brigade. The remains of II Corps from La Bassée, held a 3,500 yd (3,200 m) front, with 7,800 men and 2,000 reserves against 25 German battalions with 17,500 men. The British were forced back by the German 4th Division and British counter-attacks were repulsed.[46] Next day, an unprecedented bombardment fell on British positions in the south of the salient between Polygon Wood and Messines. German troops broke through along the Menin road but could not be supported and the advance was contained by 13 November.[47] Both sides were exhausted by these efforts; German casualties around Ypres had reached about 80,000 men and BEF losses, August – 30 November, were 89,964, 54,105 at Ypres. The Belgian army had been reduced by half and the French had lost 385,000 men by September, 265,000 men having been killed by the end of the year.[48]

Local operations, 12–22 November

The weather became much colder, with rain from 12–14 November and a little snow on 15 November. Night frosts followed and on 20 November, the ground was covered by snow. Frostbite cases appeared and the physical strain increased, among troops occupying trenches half-full of freezing water, falling asleep standing up and being sniped at and bombed from opposing trenches 100 yd (91 m) away.[49] On 12 November, a German attack surprised the French IX Corps and the British 8th Division arrived at the front on 13 November and more attacks were made on the II Corps front from 14 November. Between 15–22 November, I Corps was relieved by the French IX and XVI corps and the British line was reorganised.[50] On 16 November, Foch agreed with French to take over the line from Zonnebeke to the Ypres–Comines canal. The new British line ran 21 mi (34 km) from Wytschaete to the La Bassée Canal at Givenchy. The Belgians held 15 mi (24 km) and the French defended some 430 mi (690 km) of the new Western front. On 17 November, Albrecht ordered the 4th Army to cease its attacks; the III Reserve Corps and XIII Corps were ordered to move the Eastern Front, which was discovered by the Allies on 20 November.[51]

Aftermath

Analysis

Both sides had tried to advance after the "open" northern flank had disappeared, the Franco-British towards Lille in October, followed by attacks by the BEF, Belgians and a new French Eighth Army in Belgium. The German 4th and 6th armies took small amounts of ground at great cost to both sides, at the Battle of the Yser (16–31 October) and further south at the Battles of Ypres. Falkenhayn then tried a limited goal of capturing Ypres and Mount Kemmel, from 19 October – 22 November. By 8 November, Falkenhayn had accepted that the coastal advance had failed and that taking Ypres was impossible. Neither side had moved forces to Flanders fast enough to obtain a decisive victory and both were exhausted, short of ammunition and suffering from collapses in morale, some infantry units refusing orders. The autumn battles in Flanders had quickly become static, attrition operations, unlike the battles of manoeuvre in the summer. French, British and Belgian troops in improvised field defences repulsed German attacks for four weeks in mutually costly attacks and counter-attacks. From 21–23 October, German reservists had made mass attacks at Langemarck, with losses of up to 70 percent.[52]

Industrial warfare between mass armies had been indecisive; troops could only move forward over heaps of dead. Field fortifications had neutralised many classes of offensive weapon and the defensive firepower of artillery and machine-guns had dominated the battlefield; the ability of the armies to supply themselves and replace casualties kept battles going for weeks. The German armies engaged 34 divisions in the Flanders battles, the French twelve, the British nine and the Belgians six, along with marines and dismounted cavalry.[53] Falkenhayn reconsidered German strategy, because Vernichtungsstrategie and a dictated peace against France and Russia, were beyond German resources. Falkenhayn intended to detach Russia or France from the Allied coalition, by diplomatic as well as military action. A strategy of attrition (Ermattungsstrategie), would make the cost of the war was too great for the Allies to bear, until one enemy negotiated an end to the war. The remaining belligerents would have to come to terms or face the German army concentrated on the remaining front and capable of obtaining a decisive victory.[54]

Mad minute

In 2010, Sheldon wrote that a mad minute of accurate rapid rifle-fire, was held to have persuaded German troops that they were opposed by machine-guns. This was a false notion, picked out of a translation of Die Schlacht an der Yser und bei Ypern im Herbst 1914 (1918), which the Official Historians used in lieu of authoritative sources, during the writing of the 1914 volumes of the British Official History, the first editions of which were published in 1922 and 1925,

The British and French artillery fired as rapidly as they knew how and over every bush, hedge and fragment of wall floated a thin film of smoke, betraying a machine-gun rattling out bullets.

— Sheldon[55]

Sheldon wrote that the translation was inaccurate and ignored many references to the combined fire of rifles and machine-guns,

The British, most of whom had experience gained through long years of campaigning against cunning opponents in close country, let the attackers get to close range then, from hedges, houses and trees, opened up with withering rifle and machine-gun fire from point blank range.

— Sheldon[56]

typical of German regimental histories. The British fired short bursts at close range, to conserve ammunition. Sheldon also wrote that German troops knew the firing characteristics of machine-guns and kept still until French Hotchkiss M1909 and Hotchkiss M1914 machine-guns, which had ammunition in 24- and 30-round strips, were reloading.[57]

Kindermord

| Month | Losses |

|---|---|

| August | 14,409 |

| September | 15,189 |

| October | 30,192 |

| November | 24,785 |

| December | 11,079 |

| Total | 95,654 |

Sheldon wrote that a German description of the fate of the new reserve corps as Kindermord (massacre of the innocents), in a communiqué of 11 November 1914, was misleading. Claims that up to 75 percent of the manpower of the reserve corps were student volunteers, who attacked while singing Deutschland über alles began a myth. After the war, most regiments which had fought in Flanders, referred to the singing of songs on the battlefield, a practice only plausible when used to identify units at night.[59] In 1986, Unruh, wrote that 40,761 students had been enrolled in six reserve corps, four of which had been sent to Flanders, leaving a maximum of 30 percent of the reserve corps operating in Flanders made up of volunteers. Only 30 percent of German casualties at Ypres were young and inexperienced student reservists, others being active soldiers, older members of the Landwehr and army reservists. Reserve Infantry Regiment 211 had 166 men in active service, 299 members of the reserve, which was composed of former soldiers from 23–28 years old, 970 volunteers who were inexperienced and probably 18–20 years old, 1,499 Landwehr (former soldiers from 28–39 years old, released from the reserve) and one Ersatzreservist (enrolled but inexperienced).[60]

Casualties

In 1925, Edmonds recorded that the Belgians had suffered a great number of casualties from 15–25 October, including 10,145 wounded. British casualties from 14 October – 30 November were 58,155, French losses were 86,237 men and of 134,315 German casualties in Belgium and northern France, from 15 October – 24 November, 46,765 losses were incurred on the front from the Lys to Gheluvelt, from 30 October – 24 November.[61] In 2003, Beckett recorded 50,000–85,000 French casualties, 21,562 Belgian casualties, 55,395 British losses and 134,315 German casualties.[62] In 2010, Sheldon recorded 54,000 British casualties, c. 80,000 German casualties, that the French had many losses and that the Belgian army had been reduced to a shadow.[63] Sheldon also noted that Colonel Fritz von Lossberg had recorded that up to 3 November, casualties in the 4th Army were 62,000 men and that the 6th Army had lost 27,000 men, 17,250 losses of which had occurred in Armeegruppe Fabeck from 30 October – 3 November.[64]

Subsequent operations

Winter operations from November 1914 to February 1915 in the Ypres area, took place in the Attack on Wytschaete (14 December).[65] A reorganisation of the defence of Flanders had been carried out by the Franco-British from 15–22 November, which left the BEF holding a homogeneous front from Givenchy to Wytschaete 21 mi (34 km) to the north.[66] Joffre arranged for a series of attacks on the Western Front, after receiving information that German divisions were moving to the Russian Front. The Eighth Army was ordered to attack in Flanders and French was asked to participate with the BEF on 14 December. Joffre wanted the British to attack along all of the BEF front and especially from Warneton to Messines, as the French attacked from Wytschaete to Hollebeke. French gave orders to attack from the Lys to Warneton and Hollebeke with II and III Corps, as IV and Indian corps conducted local operations, to fix the Germans to their front.[67]

French emphasised that the attack would begin on the left flank, next to the French and that units must not move ahead of each other. The French and the 3rd Division were to capture Wytschaete and Petit Bois, then Spanbroekmolen was to be taken by II Corps attacking from the west and III Corps from the south, only the 3rd Division making a maximum effort. On the right the 5th Division was only to pretend to attack and III Corps was to make demonstrations, as the corps was holding a 10 mi (16 km) front and could do no more.[67] On the left, the French XVI Corps failed to reach its objectives and the 3rd Division got to within 50 yd (46 m) of the German line and found uncut wire. One battalion took 200 yd (180 m) of the German front trench and took 42 prisoners. The failure of the attack on Wytschaete resulted in the attack further south being cancelled but German artillery retaliation was much heavier than the British bombardment.[68]

Desultory attacks were made from 15–16 December which, against intact German defences and deep mud, made no impression. On 17 December, XVI and II corps did not attack, the French IX Corps sapped forward a short distance down the Menin road and small gains were made at Klein Zillebeke and Bixschoote. Joffre ended attacks in the north, except for operations at Arras and requested support from French who ordered attacks on 18 December along the British front, then restricted the attacks to support of XVI Corps by II Corps and demonstrations by II Corps and the Indian Corps. Fog impeded the Arras attack and a German counter-attack against XVI Corps led II Corps to cancel its supporting attack. Six small attacks were made by the 8th, 7th, 4th and Indian divisions, which captured little ground, all of which was found to be untenable due to mud and water-logging; Franco-British attacks in Flanders ended.[68]

Notes

- Four battles involving the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) occurred simultaneously during the First Battle of Flanders: the Battle of La Bassée (10 October – 2 November) from the Beuvry–Béthune road to a line from Estaires to Fournes, the Battle of Armentières (13 October – 2 November) from Estaires to the Douve river, the Battle of Messines (12 October – 2 November) from the Douve to the Ypres–Comines Canal and the Battles of Ypres (19 October – 22 November), comprising the Battle of Langemarck (21–24 October), the Battle of Gheluvelt (29–31 October) and the Battle of Nonne Bosschen (11 November) from the Ypres–Comines Canal north to Houthulst Forest.

- German armies are rendered in numbers: "7th Army" and Allied armies in words: "Second Army".

- Writers and historians have criticised the term Race to the Sea and used several date ranges. In 1925, James Edmonds the British official historian, used dates of 15 September – 15 October and 17 September – 19 October, in 1926[15][16] In 1929 in Der Weltkrieg the German Official Historians, described German outflanking attempts, without labelling them.[17] In 2001, Strachan used 15 September – 17 October.[18] In, 2003 Clayton gave dates from 17 September – 7 October.[19] In 2005, Doughty used the period from 17 September to 17 October and Foley from 17 September to 10–21 October.[20][21] In 2010, Sheldon placed the "erroneously named" race, from the end of the Battle of the Marne, to the beginning of the Battle of the Yser.[22]

- The British Battles Nomenclature Committee (1920), recorded four simultaneous battles, the Battle of La Bassée (10 October – 2 November), the Battle of Armentières (13 October – 2 November), the Battle of Messines (12 October – 2 November) and the Battles of Ypres (19 October – 22 November), comprising the Battle of Langemarck (21–24 October), the Battle of Gheluvelt (29–31 October) and the Battle of Nonne Bosschen (11 November).[26] In 1925, James Edmonds, the British Official Historian, wrote that the II Corps battle at La Bassée was separate but the battles from Armentières to Messines and Ypres, were better understood as one battle in two parts, an offensive by III Corps and the Cavalry Corps from 12–18 October and the offensive by the German 6th and 4th armies from 19 October – 2 November, which after 30 October, took place north of Armentières, when the battles of Armentières and Messines merged with the First Battle of Ypres.[27]

- Armeegruppe was a German term for a formation larger than a corps and smaller than an army, usually improvised and not a group of armies, which was a Heeresgruppe.

Footnotes

- Skinner & Stacke 1922, pp. 13–14.

- Skinner & Stacke 1922, pp. 14–16.

- James 1990, pp. 1–3.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 241, 266.

- Herwig 2009, p. 255.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 39–65.

- Raleigh 1969, pp. 371–374.

- Raleigh 1969, pp. 375–390.

- Corbett 2009, pp. 168–170.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 405.

- Corbett 2009, pp. 170–202.

- Edmonds 1926, pp. 405, 407.

- Edmonds 1926, p. 408.

- Foley 2007, p. 101.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 27–100.

- Edmonds 1926, pp. 400–408.

- Reichsarchiv 1929, p. 14.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 266–273.

- Clayton 2003, p. 59.

- Doughty 2005, p. 98.

- Foley 2007, pp. 101–102.

- Sheldon 2010, p. x.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 98–102.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 125–172, 205–223, 225–234.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 102–103.

- James 1990, pp. 4–5.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 125–126.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 73–74.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 74–76.

- Farndale 1986, pp. 67, 69.

- Farndale 1986, pp. 69–71.

- Sheldon 2010, p. viii.

- Farndale 1986, p. 71.

- Foch 1931, p. 143.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 127.

- Foley 2007, p. 102.

- Sheldon 2010, p. 79.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 275–276.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. xv, 166–167.

- Strachan 2001, p. 276.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 166–167.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 202.

- Sheldon 2010, pp. 223–224.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. xvii–xviii, 275–276.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. xviii, 278–301.

- Beckett 2006, pp. 213–214.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 277–278.

- Strachan 2001, p. 278.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 448.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. xxi, 447–460.

- Beckett 2006, pp. 219–224.

- Foley 2007, pp. 102–104.

- Philpott 2014, pp. 62, 65.

- Foley 2007, pp. 105–107.

- Schwink 1918, p. 94.

- Sheldon 2010, p. xi.

- Sheldon 2010, pp. xi–xii.

- War Office 1922, p. 253.

- Sheldon 2010, pp. xii–xiii.

- Unruh 1986, p. 65.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 466–468.

- Beckett 2006, p. 176.

- Sheldon 2010, p. xiv.

- Sheldon 2010, p. 264.

- James 1990, p. 6.

- Edmonds & Wynne 1995, p. 4.

- Edmonds & Wynne 1995, pp. 16–17.

- Edmonds & Wynne 1995, pp. 18–20.

References

Books

- Beckett, I. (2006) [2003]. Ypres: The First Battle, 1914 (pbk. ed.). London: Longmans. ISBN 978-1-4058-3620-3.

- Clayton, A. (2003). Paths of Glory: The French Army 1914–18. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35949-3.

- Corbett, J. S. (2009) [1938]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 978-1-84342-489-5. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Der Herbst-Feldzug im Osten bis zum Rückzug Im Westem bis zum Stellungskrieg [The Autumn Campaign in the East and the West until the Withdrawal and Position Warfare]. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Militärischen Operationen zu Lande. V (online scan ed.). Berlin: Verlag Ernst Siegfried Mittler & Sohn. 1929. OCLC 838299944. Retrieved 5 March 2015 – via Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic victory, French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II. London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (1995) [1927]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Winter 1915: Battle of Neuve Chapelle: Battles of Ypres. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-218-0.

- Farndale, M. (1986). History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Western Front 1914–18. London: Royal Artillery Institution. ISBN 978-1-870114-00-4.

- Foch, F. (1931). Mémoire pour servir à l'histoire de la guerre 1914–1918: avec 18 gravures hors-texte et 12 cartes [The Memoirs of Marshal Foch] (PDF) (in French). trans. T. Bentley Mott (Heinemann ed.). Paris: Plon. OCLC 86058356. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Herwig, H. (2009). The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle that Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6671-1.

- James, E. A. (1990) [1924]. A Record of the Battles and Engagements of the British Armies in France and Flanders 1914–1918 (London Stamp Exchange ed.). Aldershot: Gale & Polden. ISBN 978-0-948130-18-2.

- Philpott, W. (2014). Attrition: Fighting the First World War. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0355-7.

- Raleigh, W. A. (1969) [1922]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. I (Hamish Hamilton ed.). Oxford: OUP. OCLC 785856329. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Schwink, O. (1919) [1918]. Die Schlacht an der Yser und bei Ypern im Herbst 1914 [Ypres, 1914, an Official Account Published by Order of the German General Staff]. trans. G. C. Wynne (Constable ed.). Oldenburg: Gerhard Stalling. OCLC 3288637. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Sheldon, J. (2010). The German Army at Ypres 1914 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-113-0.

- Skinner, H. T.; Stacke, H. Fitz M. (1922). Principal Events 1914–1918. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. London: HMSO. OCLC 17673086. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War, 1914–1920. London: HMSO. 1922. OCLC 610661991. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Unruh, K. (1986). Langemarck: Legende und Wirklichkeit [Langemarck: Legend and Reality] (in German). Koblenz: Bernard & Graefe. ISBN 978-3-7637-5469-4.

Further reading

Books

- Armée Belgique: The war of 1914 Military Operations of Belgium in Defence of the Country and to Uphold Her Neutrality. London: W. H. & L Collingridge. 1915. OCLC 8651831. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Ashby, J. (2000). Seek Glory Now Keep Glory: The Story of the 1st Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment, 1914–1918. Helion. ISBN 978-1-874622-45-1.

- Beckett, I.; Simpson, K. (1985). A Nation in Arms: A Social Study of the British Army in the First World War. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-1737-7.

- Bidwell, S.; Graham, D. (1982). Fire-Power: The British Army Weapons and Theories of War, 1904–1945. London: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-216-2.

- Chapman-Huston, D.; Rutter, O. (1924). General Sir John Cowans, G.C.B., G.C.M.G: The Quartermaster-General of the Great War. I. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 792870994.

- Erdmann, K. D., ed. (1972). Kurt Riezler: Tagebücher, Aufsätze, Dokumente [Kurt Riezler: Diaries, Articles, Documents]. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-35817-7.

- Evans, M. M. (1997). Passchendaele and the Battles of Ypres 1914–1918. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-734-4.

- Farrar-Hockley, A. (1998) [1967]. Death of an Army (Wordsworth Editions ed.). London: Barker. ISBN 978-1-85326-698-0.

- Gardner, N. (2006). Trial by Fire: Command and the British Expeditionary Force in 1914. London: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-582-50612-1.

- Griffith, P. (1996). Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army's Art of Attack 1916–1918. London: Yale. ISBN 978-0-300-06663-0.

- Holmes, R. (2001). The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860696-3.

- Hussey, A. H.; Inman, D. S. (1921). The Fifth Division in the Great War. London: Nisbet & Co. OCLC 865491406. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. II (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-413-0. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Lomas, D. (2004). First Ypres 1914: The Birth of Trench Warfare. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-275-98291-1.

- Marden, T. O. (1920). A Short History of the 6th Division August 1914 – March 1919. London: Hugh Rees. OCLC 752897173. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- McGreal, S. (2010). Boesinghe: Battleground Ypres. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84884-046-1.

- Van Pul, P. (2006). In Flanders Flooded Fields, before Ypres there was Yser. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-492-0.

- Pawly, R.; Lierneux, P. (2009). The Belgian Army in World War I. Men at Arms. ISBN 978-1-84603-448-0.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (2004) [1992]. Command on the Western Front: The Military Career of Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1914–1918 (Pen & Sword ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-84415-103-5.

- Seton, B. (1915). An Analysis of 1,000 Wounds and Injuries Received in Action, with Special Reference to the Theory of the Prevalence of Self-Infliction (Secret). no ISBN. London: War Office. IOR/L/MIL/17/5/2402. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Sheffield, G.; Todman, G. (2004). Command and Control on the Western Front: The British Army's Experience 1914–18. London: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-420-4.

- Sheldon, J. (2010). The German Army at Ypres 1914. London: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-113-0.

- Wilson, T. (1986). The Myriad Faces of War: Britain and the Great War, 1914–1918. Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-0645-3.

- Wyrall, E. (2002) [1921]. The History of the Second Division, 1914–1918. I (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Thomas Nelson and Sons. OCLC 800898772. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

Journals

- Taylor, M. G. (1921). "Land Transportation in the Late War". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. 66 (464): 699–722. doi:10.1080/03071842109434650. ISSN 0035-9289. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

Websites

- Rickard, J. (1 September 2007). "Siege of Maubeuge, 25 August – 7 September 1914". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Battle of Ypres. |