French invasion of Russia

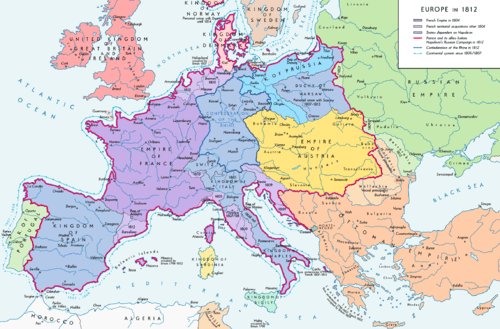

The French invasion of Russia, known in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812 (Russian: Отечественная война 1812 года, romanized: Otechestvennaya voyna 1812 goda) and in France as the Russian campaign (French: Campagne de Russie), began on 24 June 1812 when Napoleon's Grande Armée crossed the Neman River in an attempt to engage and defeat the Russian Army.[16] Napoleon hoped to compel the Emperor of All Russia, Alexander I, to cease trading with British merchants through proxies in an effort to pressure the United Kingdom to sue for peace.[17] The official political aim of the campaign was to liberate Poland from the threat of Russia. Napoleon named the campaign the Second Polish War to gain favor with the Poles and to provide a political pretext for his actions.[18]

At the start of the invasion, the Grande Armée numbered around 685,000 soldiers (including 400,000 soldiers from France). It was the largest army ever known to have been assembled in the history of European warfare up to that point.[19] Through a series of long marches Napoleon pushed his army rapidly through Western Russia in an attempt to destroy the Russian Army, winning a number of minor engagements and a major battle, the Battle of Smolensk in August. Napoleon hoped this battle would win the war for him, but the Russian Army slipped away and continued to retreat, leaving Smolensk to burn.[20] As their army fell back, the Russians employed scorched-earth tactics, destroying villages, towns and crops and forcing the invaders to rely on a supply system that was incapable of feeding their large army in the field.[17][21] On 7 September the French caught up with the Russian Army, which had dug itself in on hillsides before the small town of Borodino, seventy miles west of Moscow. The following Battle of Borodino, the bloodiest single-day action of the Napoleonic Wars, with 72,000 casualties, resulted in a narrow French victory. The Russian Army withdrew the following day, leaving the French again without the decisive victory Napoleon sought.[22] A week later, Napoleon entered Moscow, only to find it abandoned, and the city was soon ablaze, with the French blaming the fire on Russian arsonists.

The capture of Moscow did not compel Alexander I to sue for peace, and Napoleon stayed in Moscow for a month, waiting for a peace offer that never came. On 19 October 1812 Napoleon and his army left Moscow and marched southwest toward Kaluga, where Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov was encamped with the Russian Army. After the inconclusive Battle of Maloyaroslavets, Napoleon began to retreat back to the Polish border. In the following weeks, the Grande Armée suffered from the onset of the Russian Winter. Lack of food and fodder for the horses, hypothermia from the bitter cold and persistent guerilla warfare upon isolated troops from Russian peasants and Cossacks led to great losses in men, and a breakdown of discipline and cohesion in the Grande Armée. More fighting at the Battle of Vyazma and the Battle of Krasnoi resulted in further losses for the French. When the remnants of Napoleon's main army crossed the Berezina River in late November, only 27,000 soldiers remained; the Grande Armée had lost some 380,000 men dead and 100,000 captured during the campaign.[23] Following the crossing of the Berezina, Napoleon left the army after much urging from his advisors and with the unanimous approval of his Marshals.[24] He returned to Paris to protect his position as Emperor of the French and to raise more forces to resist the advancing Russians. The campaign ended after nearly six months on 14 December 1812, with the last French troops leaving Russian soil.

The campaign proved a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars.[1] It was the greatest and bloodiest of the Napoleonic campaigns, involving more than 1.5 million soldiers, with over 500,000 French and 400,000 Russian casualties.[14] The reputation of Napoleon suffered severely, and French hegemony in Europe weakened dramatically. The Grande Armée, made up of French and allied invasion forces, was reduced to a fraction of its initial strength. These events triggered a major shift in European politics. France's ally Prussia, soon followed by the Austrian Empire, broke their imposed alliance with France and switched sides. This triggered the War of the Sixth Coalition (1813–1814).[25]

Causes

Although the French Empire seemed to be at its peak in 1810 and 1811,[26] it had in fact already declined somewhat from its apogee in 1806–1809. Although most of Western and Central Europe lay under his control—either directly or indirectly through various protectorates, allies, and countries defeated by his empire and under treaties favorable for France—Napoleon had embroiled his armies in the costly and drawn-out Peninsular War in Spain and Portugal. France's economy, army morale, and political support at home had also declined. But most importantly, Napoleon himself was not in the same physical and mental state as in years past. He had become overweight and increasingly prone to various maladies.[27] Nevertheless, despite his troubles in Spain, with the exception of British expeditionary forces to that country, no European power dared to oppose him.[28]

The Treaty of Schönbrunn, which ended the 1809 war between Austria and France, had a clause removing Western Galicia from Austria and annexing it to the Grand Duchy of Warsaw. Russia viewed this as against its interests and as a potential launching point for an invasion of Russia.[29] In 1811 the Russian general staff developed a plan of an offensive war, assuming a Russian assault on Warsaw and on Danzig.[30]

In an attempt to gain increased support from Polish nationalists and patriots, Napoleon in his own words termed this war the Second Polish War.[31] Napoleon coined the War of the Fourth Coalition as the "first" Polish war because one of the officials declared goals of this war was the resurrection of the Polish state on territories of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Tsar Alexander I found Russia in an economic bind as his country had little in the way of manufacturing, yet was rich in raw materials and relied heavily on trade with Napoleon's continental system for both money and manufactured goods. Russia's withdrawal from the system was a further incentive to Napoleon to force a decision.[32]

Logistics

The invasion of Russia clearly and dramatically demonstrates the importance of logistics in military planning, especially when the land will not provide for the number of troops deployed in an area of operations far exceeding the experience of the invading army.[33] Napoleon made extensive preparations providing for the provisioning of his army.[34] The French supply effort was far greater than in any of the previous campaigns.[35] Twenty train battalions, comprising 7,848 vehicles, were to provide a 40-day supply for the Grande Armée and its operations, and a large system of magazines was established in towns and cities in Poland and East Prussia.[36][37] Napoleon studied Russian geography and the history of Charles XII's invasion of 1708–1709 and understood the need to bring forward as many supplies as possible.[34] The French Army already had previous experience of operating in the lightly populated and underdeveloped conditions of Poland and East Prussia during the War of the Fourth Coalition in 1806–1807.[34]

Napoleon and the Grande Armée had developed a proclivity for living off the land that had served it well in the densely populated and agriculturally rich central Europe with its dense network of roads.[38] Rapid forced marches had dazed and confused old order Austrian and Prussian armies and much had been made of the use of foraging.[38] Forced marches in Russia often made troops do without supplies as the supply wagons struggled to keep up,[38] furthermore horsedrawn wagons and artillery were stalled by lack of roads which often turned to mud due to rainstorms.[39] Lack of food and water in thinly populated, much less agriculturally dense regions led to the death of troops and their mounts by exposing them to waterborne diseases from drinking from mud puddles and eating rotten food and forage. The front of the army received whatever could be provided while the formations behind starved.[40] Many of the Grande Armée's methods of operation worked against it and they were additionally seriously handicapped by the lack of winter horseshoes which made it impossible for the horses to obtain traction on snow and ice.[41]

Organization

The Vistula river valley was built up in 1811–1812 as a supply base.[34] Intendant General Guillaume-Mathieu Dumas established five lines of supply from the Rhine to the Vistula.[35] French-controlled Germany and Poland were organized into three arrondissements with their own administrative headquarters.[35] The logistical buildup that followed was a testament to Napoleon's administrative skill, who devoted his efforts during the first half of 1812 largely on the provisioning of his invasion army.[34] The French logistic effort was characterized by John Elting as "amazingly successful".[35]

Ammunition

A massive arsenal was established in Warsaw.[34] Artillery was concentrated at Magdeburg, Danzig, Stettin, Küstrin and Glogau.[42] Magdeburg contained a siege artillery train with 100 heavy guns and stored 462 cannons, two million paper cartridges and 300,000 pounds/135 tonnes of gunpowder; Danzig had a siege train with 130 heavy guns and 300,000 pounds of gunpowder; Stettin contained 263 guns, a million cartridges and 200,000 pounds/90 tonnes of gunpowder; Küstrin contained 108 guns and a million cartridges; Glogau contained 108 guns, a million cartridges and 100,000 pounds/45 tonnes of gunpowder.[42] Warsaw, Danzig, Modlin, Thorn and Marienburg became ammunition and supply depots as well.[34]

Provisions

Danzig contained enough provisions to feed 400,000 men for 50 days.[42] Breslau, Plock and Wyszogród were turned into grain depots, milling vast quantities of flour for delivery to Thorn, where 60,000 biscuits were produced every day.[42] A large bakery was established at Villenberg.[35] 50,000 cattle were collected to follow the army.[35] After the invasion began, large magazines were constructed at Vilnius, Kaunas and Minsk with the Vilnius base having rations sufficient to feed 100,000 men for 40 days.[35] It also contained 27,000 muskets, 30,000 pairs of shoes along with brandy and wine.[35] Medium-sized depots were established at Smolensk, Vitebsk and Orsha, along with several small ones throughout the Russian interior.[35] The French also captured numerous intact Russian supply dumps, which the Russians had failed to destroy or empty, and Moscow itself was filled with food.[35] Despite the logistical problems faced by the Grande Armée as a whole, the main strike force got to Moscow without much in the way of hunger.[43] Indeed, the French spearheads lived well on the basis of pre-prepared stocks and forage.[43]

Combat service and support and medicine

Nine pontoon companies, three pontoon trains with 100 pontoons each, two companies of marines, nine sapper companies, six miner companies and an engineer park were deployed for the invasion force.[42] Large-scale military hospitals were created at Warsaw, Thorn, Breslau, Marienburg, Elbing and Danzig,[42] while hospitals in East Prussia had beds for 28,000 alone.[35]

Transportation

Twenty train battalions provided most of the transportation, with a combined load of 8,390 tons.[42] Twelve of these battalions had a total of 3,024 heavy wagons drawn by four horses each, four had 2,424 one-horse light wagons and four had 2,400 wagons drawn by oxen.[42] Auxiliary supply convoys were formed on Napoleon's orders in early June 1812, using vehicles requisitioned in East Prussia.[44] Marshal Nicolas Oudinot's IV Corps alone took 600 carts formed into six companies.[45] The wagon trains were supposed to carry enough bread, flour and medical supplies for 300,000 men for two months.[45] Two river flotillas at Danzig and Elbing carried enough supplies for 11 days.[42] The Danzig flotilla sailed by way of canals to the Niemen river.[42] After the war began, the Elbing flotilla assisted in building up forward depots at Tapiau, Insterburg, and Gumbinnen.[42]

Deficiencies

Despite all these preparations, the Grande Armée was still not fully self-sufficient logistically and still depended on foraging to a significant extent.[44] Napoleon already faced difficulties providing for his 685,000-man, 180,000-horse army on friendly territory in Poland and Prussia.[44] The standard heavy wagons, well-suited for the dense and partially paved road networks of Germany and France proved too cumbersome for the sparse and primitive Russian dirt tracks.[5] The supply route from Smolensk to Moscow was therefore entirely dependent on light wagons with small loads.[45] The heavy losses to disease, hunger and desertion in the early months of the campaign were in large part due to the inability to transport provisions quickly enough to the troops.[5] A large portion of the army consisted of partially-trained, unmotivated recruits that lacked training in the fieldcraft and foraging techniques that had proven so successful in earlier campaigns, and were paralyzed without a constant stream of supplies.[46] Some exhausted soldiers threw away their reserve rations in the summer heat.[43] Forage was scarce after a late, dry spring, leading to great losses of horses.[43] 10,000 horses were lost due to a great storm in the opening weeks of the campaign.[43]

Many of the commanders lacked the operational and administrative skills and apparatus to efficiently move so many troops across such large distances of hostile territory.[46] The supply depots established by the French in the Russian interior, while extensive, were too far behind the main army.[47] The Intendance administration failed to distribute with sufficient rigor the supplies that were built up or captured.[35] Some of the administrative officials fled prematurely from their depots during the retreat, leaving them to be used up indiscriminately by the starving soldiers.[43] The French train battalions moved forward huge amounts of supplies during the campaign, but the distances and speed required, a lack of discipline and training in the newer formations and reliance on defective, requisitioned vehicles that broke down easily meant that the demands Napoleon placed on them were too great.[48] Of the 7,000 officers and men in the train battalions, 5,700 became casualties.[48]

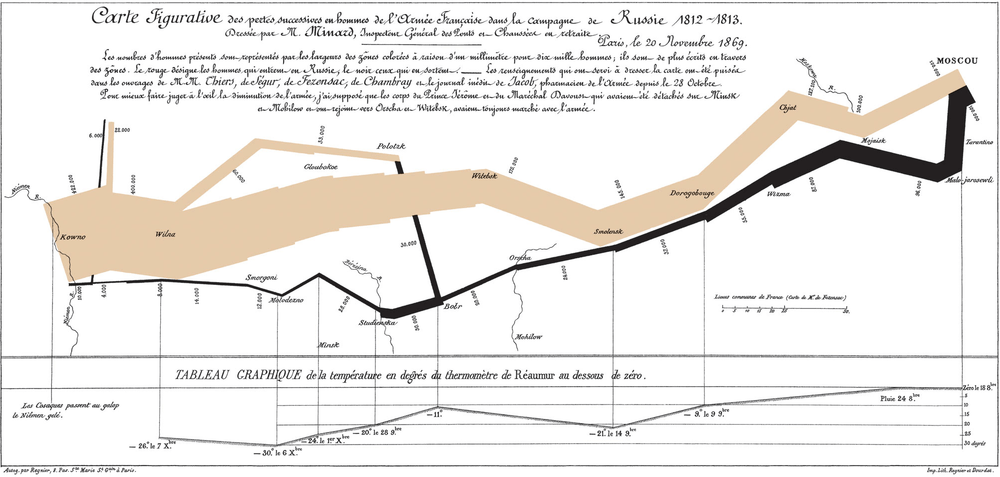

Napoleon intended to trap and destroy the Russian Army on the frontier or before Smolensk.[49] He would fortify Smolensk and Minsk, establish forward supply depots in Lithuania and winter quarters at Vilnius and wait for either peace negotiations or a continuation of the campaign in the spring.[49] Aware of the vast distances that could undo his army, Napoleon's original plan did not have him continuing beyond Smolensk in 1812.[49] However, the Russian armies could not stand singularly against the main battle group of 285,000 men and continued to retreat and attempt to join one another. This demanded an advance by the Grande Armée over a network of dirt roads that dissolved into deep mires, where ruts in the mud froze solid, killing already exhausted horses and breaking wagons.[50] As the graph of Charles Joseph Minard, given below, shows, the Grande Armée incurred the majority of its losses during the march to Moscow during the summer and autumn.

Opposing forces

Grande Armée

On 24 June 1812, the 685,000 men of the Grande Armée, the largest army assembled up to that point in European history, crossed the Neman River and headed towards Moscow. Anthony Joes wrote in the Journal of Conflict Studies that:

Figures on how many men Napoleon took into Russia and how many eventually came out vary widely.

- [Georges] Lefebvre says that Napoleon crossed the Neman with over 600,000 soldiers, only half of whom were from France, the others being mainly Poles and Germans.

- Felix Markham thinks that 450,000 crossed the Neman on 25 June 1812, of whom fewer than 40,000 recrossed in anything like a recognizable military formation.

- James Marshall-Cornwall says 510,000 Imperial troops entered Russia.

- Eugene Tarle believes that 420,000 crossed with Napoleon and 150,000 eventually followed, for a grand total of 570,000.

- Richard K. Riehn provides the following figures: 685,000 men marched into Russia in 1812, of whom around 355,000 were French; 31,000 soldiers marched out again in some sort of military formation, with perhaps another 35,000 stragglers, for a total of fewer than 70,000 known survivors.

- Adam Zamoyski estimated that between 550,000 and 600,000 French and allied troops (including reinforcements) operated beyond the Nemen, of which as many as 400,000 troops died.[51]

"Whatever the accurate number, it is generally accepted that the overwhelming majority of this grand army, French and allied, remained, in one condition or another, inside Russia."

— Anthony Joes[52]

Minard's famous infographic (see below) depicts the march ingeniously by showing the size of the advancing army, overlaid on a rough map, as well as the retreating soldiers together with temperatures recorded (as much as 30 below zero on the Réaumur scale (−38 °C, −36 °F)) on their return. The numbers on this chart have 422,000 crossing the Neman with Napoleon, 22,000 taking a side trip early on in the campaign, 100,000 surviving the battles en route to Moscow and returning from there; only 4,000 survive the march back, to be joined by 6,000 that survived from that initial 22,000 in the feint attack northward; in the end, only 10,000 crossed the Neman back out of the initial 422,000.[53]

Imperial Russian Army

General of Infantry Mikhail Bogdanovich Barclay de Tolly served as the Commander in Chief of the Russian Armies, a field commander of the First Western Army and Minister of War, Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov replaced him, and assumed the role of Commander-in-chief during the retreat following the Battle of Smolensk.

These forces, however, could count on reinforcements from the second line, which totaled 129,000 men and 8,000 Cossacks with 434 guns and 433 rounds of ammunition.

Of these, about 105,000 men were actually available for the defense against the invasion. In the third line were the 36 recruit depots and militias, which came to a total of approximately 161,000 men of various and highly disparate military values, of which about 133,000 actually took part in the defense.

Thus, the grand total of all the forces was 488,000 men, of which about 428,000 gradually came into action against the Grande Armee. This bottom line, however, includes more than 80,000 Cossacks and militiamen, as well as about 20,000 men who garrisoned the fortresses in the operational area. The majority of the officer corps came from the aristocracy.[54] About 7% of the officer corps came from the Baltic German nobility from the governorates of Estonia and Livonia.[54] Because the Baltic German nobles tended to be better educated than the ethnic Russian nobility, the Baltic Germans were often favored with positions in high command and various technical positions.[54] The Russian Empire had no universal educational system, and those who could afford it had to hire tutors and/or send their children to private schools.[54] The educational level of the Russian nobility and gentry varied enormously depending on the quality of the tutors and/or private schools with some Russian nobles being extremely well educated while others were just barely literate. The Baltic German nobility were more inclined to invest in their children's education than the ethnic Russian nobility, which led to the government favoring them when granting officers' commissions.[54] Of the 800 doctors in the Russian Army in 1812, almost all of them were Baltic Germans.[54] The British historian Dominic Lieven noted that at the time, the Russian elite defined Russianness in terms of loyalty to the House of Romanov rather in terms of language or culture, and as the Baltic German aristocrats were very loyal, they were considered and considered themselves to be Russian despite speaking German as their first language.[54]

Sweden, Russia's only ally, did not send supporting troops, but the alliance made it possible to withdraw the 45,000-man Russian corps Steinheil from Finland and use it in the later battles (20,000 men were sent to Riga).[55]

Invasion

Crossing the Niemen

The invasion commenced on 24 June 1812. Napoleon had sent a final offer of peace to Saint Petersburg shortly before commencing operations. He never received a reply, so he gave the order to proceed into Russian Poland. He initially met little resistance and moved quickly into the enemy's territory. The French coalition of forces amounted to 449,000 men and 1,146 cannons being opposed by the Russian armies combining to muster 153,000 Russians, 938 cannons, and 15,000 Cossacks.[56] The center of mass of French forces focused on Kaunas and the crossings were made by the French Guard, I, II and III corps amounting to some 120,000 at this point of crossing alone.[57] The actual crossings were made in the area of Alexioten where three pontoon bridges were constructed. The sites had been selected by Napoleon in person.[58] Napoleon had a tent raised and he watched and reviewed troops as they crossed the Neman River.[59] Roads in this area of Lithuania hardly qualified as such, actually being small dirt tracks through areas of dense forest.[60] Supply lines simply could not keep up with the forced marches of the corps and rear formations always suffered the worst privations.[61]

March on Vilnius

The 25th of June found Napoleon's group past the bridgehead with Ney's command approaching the existing crossings at Alexioten. Murat's reserve cavalry provided the vanguard with Napoleon the guard and Davout's 1st corps following behind. Eugene's command would cross the Niemen further north at Piloy, and MacDonald crossed the same day. Jerome's command wouldn't complete its crossing at Grodno until the 28th. Napoleon rushed towards Vilnius pushing the infantry forward in columns that suffered from heavy rain then stifling heat. The central group would cross 70 miles (110 km) in two days.[62] Ney's III Corps would march down the road to Sudervė with Oudinot marching on the other side of the Neris River in an operation attempting to catch General Wittgenstein's command between Ney, Oudinout and Macdonald's commands, but Macdonald's command was late in arriving to an objective too far away and the opportunity vanished. Jerome was tasked with tackling Bagration by marching to Grodno and Reynier's VII corps sent to Białystok in support.[63]

The Russian headquarters was in fact centered in Vilnius on June 24 and couriers rushed news about the crossing of the Niemen to Barclay de Tolley. Before the night had passed orders were sent out to Bagration and Platov to take the offensive. Alexander left Vilnius on June 26 and Barclay assumed overall command. Although Barclay wanted to give battle he assessed it as a hopeless situation and ordered Vilnius's magazines burned and its bridge dismantled. Wittgenstein moved his command to Perkele passing beyond Macdonald and Oudinot's operations with Wittgenstein's rear guard clashing with Oudinout's forward elements.[63] Doctorov on the Russian Left found his command threatened by Phalen's III cavalry corps. Bagration was ordered to Vileyka which moved him towards Barclay though the order's intent is still something of a mystery to this day.[64]

.gif)

On June the 28th Napoleon entered Vilnius with only light skirmishing. The foraging in Lithuania proved hard as the land was mostly barren and forested. The supplies of forage were less than that of Poland and two days of forced marching made a bad supply situation worse.[64] Central to the problem were the expanding distances to supply magazines and the fact that no supply wagon could keep up with a forced marched infantry column.[39] The weather itself became an issue where according to historian Richard K. Riehn:

The thunderstorms of the 24th turned into other downpours, turning the tracks—some diarists claim there were no roads in Lithuania—into bottomless mires. Wagon sank up to their hubs; horses dropped from exhaustion; men lost their boots. Stalled wagons became obstacles that forced men around them and stopped supply wagons and artillery columns. Then came the sun which would bake the deep ruts into canyons of concrete, where horses would break their legs and wagons their wheels.[39]

A Lieutenant Mertens—a Württemberger serving with Ney's III corps—reported in his diary that oppressive heat followed by rain left them with dead horses and camping in swamp-like conditions with dysentery and influenza raging though the ranks with hundreds in a field hospital that had to be set up for the purpose. He reported the times, dates and places, of events reporting thunderstorms on the 6th of June and men dying of sunstroke by the 11th.[39] The Crown Prince of Wurttemberg reported 21 men dead in bivouacs. The Bavarian corps was reporting 345 sick by June 13.[65]

Desertion was high among Spanish and Portuguese formations. These deserters proceeded to terrorize the population, looting whatever lay to hand. The areas in which the Grande Armée passed were devastated. A Polish officer reported that areas around him were depopulated.[65]

The French light Cavalry was shocked to find itself outclassed by Russian counterparts so much so that Napoleon had ordered that infantry be provided as back up to French light cavalry units.[65] This affected both French reconnaissance and intelligence operations. Despite 30,000 cavalry, contact was not maintained with Barclay's forces leaving Napoleon guessing and throwing out columns to find his opposition.[66]

The operation intended to split Bagration's forces from Barclay's forces by driving to Vilnius had cost the French forces 25,000 losses from all causes in a few days.[65] Strong probing operations were advanced from Vilnius towards Nemenčinė, Mykoliškės, Ashmyany and Molėtai.[65]

Eugene crossed at Prenn on June 30 while Jerome moved VII Corps to Białystok, with everything else crossing at Grodno.[66] Murat advanced to Nemenčinė on July 1 running into elements of Doctorov's III Russian Cavalry Corps en route to Djunaszev. Napoleon assumed this was Bagration's 2nd Army and rushed out before being told it was not 24 hours later. Napoleon then attempted to use Davout, Jerome, and Eugene out on his right in a hammer and anvil to catch Bagration to destroy the 2nd Army in an operation spanning Ashmyany and Minsk. This operation had failed to produce results on his left before with Macdonald and Oudinot. Doctorov had moved from Djunaszev to Svir narrowly evading French forces, with 11 regiments and a battery of 12 guns heading to join Bagration when moving too late to stay with Doctorov.[67]

Conflicting orders and lack of information had almost placed Bagration in a bind marching into Davout; however, Jerome could not arrive in time over the same mud tracks, supply problems, and weather, that had so badly affected the rest of the Grande Armée, losing 9000 men in four days. Command disputes between Jerome and General Vandamme would not help the situation.[68] Bagration joined with Doctorov and had 45,000 men at Novi-Sverzen by the 7th. Davout had lost 10,000 men marching to Minsk and would not attack Bagration without Jerome joining him. Two French Cavalry defeats by Platov kept the French in the dark and Bagration was no better informed with both overestimating the other's strength, Davout thought Bagration had some 60,000 men and Bagration thought Davout had 70,000. Bagration was getting orders from both Alexander's staff and Barclay (which Barclay didn't know) and left Bagration without a clear picture of what was expected of him and the general situation. This stream of confused orders to Bagration had him upset with Barclay which would have repercussions later.[69]

Napoleon reached Vilnius on 28 June, leaving 10,000 dead horses in his wake. These horses were vital to bringing up further supplies to an army in desperate need. Napoleon had supposed that Alexander would sue for peace at this point and was to be disappointed; it would not be his last disappointment.[70] Barclay continued to retreat to the Drissa deciding that the concentration of the 1st and 2nd armies was his first priority.[71]

Barclay continued his retreat and with the exception of the occasional rearguard clash remained unhindered in his movements ever further east.[72] To date the standard methods of the Grande Armée were working against it. Rapid forced marches quickly caused desertion, starvation, exposed the troops to filthy water and disease, while the logistics trains lost horses by the thousands, further exacerbating the problems. Some 50,000 stragglers and deserters became a lawless mob warring with local peasantry in all-out guerrilla war, that further hindered supplies reaching the Grand Armée which was already down 95,000 men.[73]

March on Moscow

Barclay, the Russian commander-in-chief, refused to fight despite Bagration's urgings. Several times he attempted to establish a strong defensive position, but each time the French advance was too quick for him to finish preparations and he was forced to retreat once more. When the French Army progressed further, it encountered serious problems in foraging, aggravated by scorched earth tactics of the Russian forces[74][75] advocated by Karl Ludwig von Phull.[76]

Political pressure on Barclay to give battle and the general's continuing reluctance to do so (viewed as intransigence by the Russian nobility) led to his removal. He was replaced in his position as commander-in-chief by the popular, veteran Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov. Kutuzov, however, continued much along the line of the general Russian strategy, fighting the occasional defensive engagement but being careful not to risk the army in an open battle. Instead, the Russian Army fell back ever deeper into Russia's interior. Following a defeat at Smolensk on August 16–18 he continued the move east. Unwilling to give up Moscow without a fight, Kutuzov took up a defensive position some 75 miles before Moscow at Borodino. Meanwhile, French plans to quarter at Smolensk were abandoned, and Napoleon pressed his army on after the Russians.[77]

The Battle of Borodino

The Battle of Borodino, fought on September 7, 1812,[78] was the largest and bloodiest battle of the French invasion of Russia, involving more than 250,000 troops and resulting in at least 70,000 casualties.[79] The French Grande Armée under Emperor Napoleon I attacked the Imperial Russian Army of General Mikhail Kutuzov near the village of Borodino, west of the town of Mozhaysk and eventually captured the main positions on the battlefield but failed to destroy the Russian army. About a third of Napoleon's soldiers were killed or wounded; Russian losses, while heavier, could be replaced due to Russia's large population, since Napoleon's campaign took place on Russian soil.

The battle ended with the Russian Army, while out of position, still offering resistance.[80] The state of exhaustion of the French forces and the lack of recognition of the state of the Russian Army led Napoleon to remain on the battlefield with his army instead of the forced pursuit that had marked other campaigns that he had conducted.[81] The entirety of the Guard was still available to Napoleon and in refusing to use it he lost this singular chance to destroy the Russian Army.[82] The battle at Borodino was a pivotal point in the campaign, as it was the last offensive action fought by Napoleon in Russia. By withdrawing, the Russian Army preserved its combat strength, eventually allowing it to force Napoleon out of the country.

The Battle of Borodino on September 7 was the bloodiest day of battle in the Napoleonic Wars. The Russian Army could only muster half of its strength on September 8. Kutuzov chose to act in accordance with his scorched earth tactics and retreat, leaving the road to Moscow open. Kutuzov also ordered the evacuation of the city.

By this point the Russians had managed to draft large numbers of reinforcements into the army bringing total Russian land forces to their peak strength in 1812 of 904,000 with perhaps 100,000 in the vicinity of Moscow—the remnants of Kutuzov's army from Borodino partially reinforced.

Retreat and rebuilding

Both armies began to move and rebuild. The Russian retreat was significant for two reasons; firstly, the move was to the south and not the east; secondly, the Russians immediately began operations that would continue to deplete the French forces. Platov, commanding the rear guard on September 8, offered such strong resistance that Napoleon remained on the Borodino field.[80] On the following day, Miloradovitch assumed command of the rear guard adding his forces to the formation. Another battle was given throwing back French forces at Semolino causing 2,000 losses on both sides, however some 10,000 wounded would be left behind by the Russian Army.[83]

The French Army began to move out on September 10 with the still ill Napoleon not leaving until the 12th. Some 18,000 men were ordered in from Smolensk, and Marshal Victor's corps supplied another 25,000.[84] Miloradovich would not give up his rearguard duties until September 14, allowing Moscow to be evacuated. Miloradovich finally retreated under a flag of truce.[85]

Capture of Moscow

.jpg)

On September 14, 1812, Napoleon moved into Moscow. However, he was surprised to have received no delegation from the city. At the approach of a victorious general, the civil authorities customarily presented themselves at the gates of the city with the keys to the city in an attempt to safeguard the population and their property. As nobody received Napoleon he sent his aides into the city, seeking out officials with whom the arrangements for the occupation could be made. When none could be found, it became clear that the Russians had left the city unconditionally.[86] In a normal surrender, the city officials would be forced to find billets and make arrangements for the feeding of the soldiers, but the situation caused a free-for-all in which every man was forced to find lodgings and sustenance for himself. Napoleon was secretly disappointed by the lack of custom as he felt it robbed him of a traditional victory over the Russians, especially in taking such a historically significant city.[86] To make matters worse, Moscow had been stripped of all supplies by its governor, Feodor Rostopchin, who had also ordered the prisons to be opened.

Before the order was received to evacuate Moscow, the city had a population of approximately 270,000 people. As much of the population pulled out, the remainder were burning or robbing the remaining stores of food, depriving the French of their use. As Napoleon entered the Kremlin, there still remained one-third of the original population, mainly consisting of foreign traders, servants, and people who were unable or unwilling to flee. These, including the several-hundred-strong French colony, attempted to avoid the troops.

On the first night of French occupation, a fire broke out in the Bazaar. There were no administrative means on hand to organize fighting the fire, and no pumps or hoses could be found. Later that night several more broke out in the suburbs. These were thought to be due to carelessness on the part of the soldiers.[87] Some looting occurred and a military government was hastily set up in an attempt to keep order. The following night the city began to burn in earnest. Fires broke out across the north part of the city, spreading and merging over the next few days. Rostopchin had left a small detachment of police, whom he charged with burning the city to the ground.[88] According to Germaine de Staël, who left the city a few weeks before Napoleon arrived, it was Rostopchin who ordered to set his mansion on fire.[89] Houses had been prepared with flammable materials.[90] The city's fire engines had been dismantled. Fuses were left throughout the city to ignite the fires.[91] French troops endeavored to fight the fire with whatever means they could, struggling to prevent the armory from exploding and to keep the Kremlin from burning down. The heat was intense. Moscow, composed largely of wooden buildings, burnt down almost completely. It was estimated that four-fifths of the city was destroyed.

Relying on classical rules of warfare aiming at capturing the enemy's capital (even though Saint Petersburg was the political capital at that time, Moscow was the spiritual capital of Russia), Napoleon had expected Tsar Alexander I to offer his capitulation at the Poklonnaya Hill but the Russian command did not think of surrendering.

Retreat and losses

Sitting in the ashes of a ruined city with no foreseeable prospect of Russian capitulation, idle troops, and supplies diminished by use and Russian operations of attrition, Napoleon had little choice but to withdraw his army from Moscow.[92] He began the long retreat by the middle of October 1812, leaving the city himself on October 19. At the Battle of Maloyaroslavets, Kutuzov was able to force the French Army into using the same Smolensk road on which they had earlier moved east, the corridor of which had been stripped of food by both armies. This is often presented as an example of scorched earth tactics. Continuing to block the southern flank to prevent the French from returning by a different route, Kutuzov employed partisan tactics to repeatedly strike at the French train where it was weakest. As the retreating French train broke up and became separated, Cossack bands and light Russian cavalry assaulted isolated French units.[92]

Supplying the army in full became an impossibility. The lack of grass and feed weakened the remaining horses, almost all of which died or were killed for food by starving soldiers. Without horses, the French cavalry ceased to exist; cavalrymen had to march on foot. Lack of horses meant many cannons and wagons had to be abandoned. Much of the artillery lost was replaced in 1813, but the loss of thousands of wagons and trained horses weakened Napoleon's armies for the remainder of his wars. Starvation and disease took their toll, and desertion soared. Many of the deserters were taken prisoner or killed by Russian peasants. Badly weakened by these circumstances, the French military position collapsed. Further, defeats were inflicted on elements of the Grande Armée at Vyazma, Polotsk and Krasny. The crossing of the river Berezina was a final French calamity; two Russian armies inflicted heavy casualties on the remnants of the Grande Armée as it struggled to escape across improvised bridges.

In early November 1812, Napoleon learned that General Claude de Malet had attempted a coup d'état in France. He abandoned the army on 5 December and returned home on a sleigh,[93] leaving Marshal Joachim Murat in command. Subsequently, Murat left what was left of the Grande Armée to try to save his Kingdom of Naples. Within a few weeks, in January 1813, he left Napoleon's former stepson, Eugène de Beauharnais, in command.

In the following weeks, the Grande Armée shrank further and on 14 December 1812, it left Russian territory. According to the popular legend, only about 22,000 of Napoleon's men survived the Russian campaign. However, some sources say that no more than 380,000 soldiers were killed.[9] The difference can be explained by up to 100,000 French prisoners in Russian hands (mentioned by Eugen Tarlé, and released in 1814) and more than 80,000 (including all wing-armies, not only the rest of the "main army" under Napoleon's direct command) returning troops (mentioned by German military historians).

Most of the Prussian contingent survived thanks to the Convention of Tauroggen and almost the whole Austrian contingent under Schwarzenberg withdrew successfully. The Russians formed the Russian-German Legion from other German prisoners and deserters.[55]

_-_detail.jpg)

Russian casualties in the few open battles are comparable to the French losses but civilian losses along the devastating campaign route were much higher than the military casualties. In total, despite earlier estimates giving figures of several million dead, around one million were killed including civilians—fairly evenly split between the French and Russians.[15] Military losses amounted to 300,000 French, about 72,000 Poles,[94] 50,000 Italians, 80,000 Germans, 61,000 from other nations. As well as the loss of human life the French also lost some 200,000 horses and over 1,000 artillery pieces.

.jpg)

The losses of the Russian armies are difficult to assess. The 19th-century historian Michael Bogdanovich assessed reinforcements of the Russian armies during the war using the Military Registry archives of the General Staff. According to this, the reinforcements totaled 134,000 men. The main army at the time of capture of Vilnius in December had 70,000 men, whereas its number at the start of the invasion had been about 150,000. Thus, total losses would come to 210,000 men. Of these about 40,000 returned to duty. Losses of the formations operating in secondary areas of operations as well as losses in militia units were about 40,000. Thus, he came up with the number of 210,000 men and militiamen.[13]

Increasingly the view that the greater part of the Grande Armée perished in Russia has been criticised. Hay has argued that the destruction of the Dutch contingent of the Grande Armée was not a result of the death of most of its members. Rather its various units disintegrated and the troops scattered. Later many of this personnel were collected and reorganised into the new Dutch army.[95]

Weather as a factor

Following the campaign a saying arose that the Generals Janvier and Février (January and February) defeated Napoleon, alluding to the Russian Winter. Although the campaign was over by mid-November, there is some truth to the saying. The coming winter weather was heavy on the minds of Napoleon's closest advisers. The army was equipped with summer clothing, and did not have the means to protect themselves from the cold.[96] In addition, it lacked the ability to forge caulkined shoes for the horses to enable them to walk over roads that had become iced over. The most devastating effect of the cold weather upon Napoleon's forces occurred during their retreat. Hypothermia coupled with starvation led to the loss of thousands. In his memoir, Napoleon's close adviser Armand de Caulaincourt recounted scenes of massive loss, and offered a vivid description of mass death through hypothermia:

The cold was so intense that bivouacking was no longer supportable. Bad luck to those who fell asleep by a campfire! Furthermore, disorganization was perceptibly gaining ground in the Guard. One constantly found men who, overcome by the cold, had been forced to drop out and had fallen to the ground, too weak or too numb to stand. Ought one to help them along – which practically meant carrying them? They begged one to let them alone. There were bivouacs all along the road – ought one to take them to a campfire? Once these poor wretches fell asleep they were dead. If they resisted the craving for sleep, another passer-by would help them along a little farther, thus prolonging their agony for a short while, but not saving them, for in this condition the drowsiness engendered by cold is irresistibly strong. Sleep comes inevitably, and sleep is to die. I tried in vain to save a number of these unfortunates. The only words they uttered were to beg me, for the love of God, to go away and let them sleep. To hear them, one would have thought sleep was their salvation. Unhappily, it was a poor wretch's last wish. But at least he ceased to suffer, without pain or agony. Gratitude, and even a smile, was imprinted on his discoloured lips. What I have related about the effects of extreme cold, and of this kind of death by freezing, is based on what I saw happen to thousands of individuals. The road was covered with their corpses.

— Caulaincourt[97]

This befell a Grande Armée that was ill-equipped for cold weather. The Russians, properly equipped, considered it a relatively mild winter – Berezina river was not frozen during the last major battle of the campaign; the French deficiencies in equipment caused by the assumption that their campaign would be concluded before the cold weather set in were a large factor in the number of casualties they suffered.[98] However, the outcome of the campaign was decided long before the weather became a factor.

Inadequate supplies played a key role in the losses suffered by the army as well. Davidov and other Russian campaign participants record wholesale surrenders of starving members of the Grande Armée even before the onset of the frosts.[99] Caulaincourt describes men swarming over and cutting up horses that slipped and fell, even before the poor creature had been killed.[100] There were even eyewitness reports of cannibalism. The French simply were unable to feed their army. Starvation led to a general loss of cohesion.[101] Constant harassment of the French Army by Cossacks added to the losses during the retreat.[99]

Though starvation and the winter weather caused horrendous casualties in Napoleon's army, losses arose from other sources as well. The main body of Napoleon's Grande Armée diminished by a third in just the first eight weeks of the campaign, before the major battle was fought. This loss in strength was in part due to desertions, the need to garrison supply centers, casualties sustained in minor actions and to diseases such as diphtheria, dysentery and typhus.[102] The central French force under Napoleon's direct command crossed the Niemen River with 286,000 men. By the time they fought the Battle of Borodino the force was reduced to 161,475 men.[103] Napoleon lost at least 30,000 men in this battle, to gain a narrow and Pyrrhic victory almost 1,000 km (620 mi) into hostile territory.

Napoleon's invasion of Russia is listed among the most lethal military operations in world history.[104]

Historical assessment

Alternative names

Napoleon's invasion of Russia is better known in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812 (Russian Отечественная война 1812 года, Otechestvennaya Vojna 1812 goda). It should not be confused with the Great Patriotic War (Великая Отечественная война, Velikaya Otechestvennaya Voyna), a term for Adolf Hitler's invasion of Russia during the Second World War. The Patriotic War of 1812 is also occasionally referred to as simply the "War of 1812", a term which should not be confused with the conflict between Great Britain and the United States, also known as the War of 1812. In Russian literature written before the Russian revolution, the war was occasionally described as "the invasion of twelve languages" (Russian: нашествие двенадцати языков). Napoleon termed this war the "First Polish War" in an attempt to gain increased support from Polish nationalists and patriots. Though the stated goal of the war was the resurrection of the Polish state on the territories of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (modern territories of Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine), in fact, this issue was of no real concern to Napoleon.[18]

Historiography

The British historian Dominic Lieven wrote that much of the historiography about the campaign for various reasons distorts the story of the Russian war against France in 1812–14.[105] The number of Western historians who are fluent in French and/or German vastly outnumbers those who are fluent in Russian, which has the effect that many Western historians simply ignore Russian language sources when writing about the campaign because they cannot read them.[106]

Memoirs written by French veterans of the campaign together with much of the work done by French historians strongly show the influence of "Orientalism", which depicted Russia as a strange, backward, exotic and barbaric "Asian" nation that was innately inferior to the West, especially France.[107] The picture drawn by the French is that of a vastly superior army being defeated by geography, the climate and just plain bad luck.[107] German language sources are not as hostile to the Russians as French sources, but many of the Prussian officers such as Carl von Clausewitz (who did not speak Russian) who joined the Russian Army to fight against the French found service with a foreign army both frustrating and strange, and their accounts reflected these experiences.[108] Lieven compared those historians who use Clausewitz's account of his time in Russian service as their main source for the 1812 campaign to those historians who might use an account written by a Free French officer who did not speak English who served with the British Army in World War II as their main source for the British war effort in the Second World War.[109]

In Russia, the official historical line until 1917 was that the peoples of the Russian Empire had rallied together in defense of the throne against a foreign invader.[110] Because many of the younger Russian officers in the 1812 campaign took part in the Decembrist uprising of 1825, their roles in history were erased at the order of Emperor Nicholas I.[111] Likewise, because many of the officers who were also veterans who stayed loyal during the Decembrist uprising went on to become ministers in the tyrannical regime of Emperor Nicholas I, their reputations were blacked among the radical intelligentsia of 19th century Russia.[111] For example, Count Alexander von Benckendorff fought well in 1812 commanding a Cossack company, but because he later become the Chief of the Third Section Of His Imperial Majesty's Chancellery as the secret police were called, was one of the closest friends of Nicholas I and is infamous for his persecution of Russia's national poet Alexander Pushkin, he is not well remembered in Russia and his role in 1812 is usually ignored.[111]

Furthermore, the 19th century was a great age of nationalism and there was a tendency by historians in the Allied nations to give the lion's share of the credit for defeating France to their own respective nation with British historians claiming that it was the United Kingdom that played the most important role in defeating Napoleon; Austrian historians giving that honor to their nation; Russian historians writing that it was Russia that played the greatest role in the victory, and Prussian and later German historians writing that it was Prussia that made the difference.[112] In such a context, various historians liked to diminish the contributions of their allies.

Leo Tolstoy was not a historian, but his extremely popular 1869 historical novel War and Peace which depicted the war as a triumph of what Lieven called the "moral strength, courage and patriotism of ordinary Russians" with military leadership a negligible factor has shaped the popular understanding of the war in both Russia and abroad from the 19th century onward.[113] A recurring theme of War and Peace is that certain events are just fated to happen, and there is nothing that a leader can do to challenge destiny, a view of history that dramatically discounts leadership as a factor in history. During the Soviet period, historians engaged in what Lieven called huge distortions to make history fit with Communist ideology, with Marshal Kutuzov and Prince Bagration transformed into peasant generals, Alexander I alternatively ignored or vilified, and the war becoming a massive "People's War" fought by the ordinary people of Russia with almost no involvement on the part of the government.[114] During the Cold War, many Western historians were inclined to see Russia as "the enemy", and there was a tendency to downplay and dismiss Russia's contributions to the defeat of Napoleon.[109] As such, Napoleon's claim that the Russians did not defeat him and he was just the victim of fate in 1812 was very appealing to many Western historians.[113]

Russian historians tended to focus on the French invasion of Russia in 1812 and ignore the campaigns in 1813–1814 fought in Germany and France because a campaign fought on Russian soil was regarded as more important than campaigns abroad and because in 1812 the Russians were commanded by the ethnic Russian Kutuzov while in the campaigns in 1813–1814 the senior Russian commanders were mostly ethnic Germans, being either Baltic German nobility or Germans who had entered Russian service.[115] At the time the conception held by the Russian elite was that the Russian empire was a multi-ethnic entity, in which the Baltic German aristocrats in service to the House of Romanov were considered part of that elite-an understanding of what it meant to be Russian defined in terms of dynastic loyalty rather than language, ethnicity, and culture that does not appeal to those later Russians who wanted to see the war as a purely a triumph of ethnic Russians.[116]

One consequence of this is that many Russian historians liked to disparage the officer corps of the Imperial Russian Army because of the high proportion of Baltic Germans serving as officers, which further reinforces the popular stereotype that the Russians won despite their officers rather than because of them.[117] Furthermore, Emperor Alexander I often gave the impression at the time that he found Russia a place that was not worthy of his ideals, and he cared more about Europe as a whole than about Russia.[115] Alexander's conception of a war to free Europe from Napoleon lacked appeal to many nationalist-minded Russian historians, who preferred to focus on a campaign in defense of the homeland rather than what Lieven called Alexander's rather "murky" mystical ideas about European brotherhood and security.[115] Lieven observed that for every book written in Russia on the campaigns of 1813–1814, there are a hundred books on the campaign of 1812 and that the most recent Russian grand history of the war of 1812–1814 gave 490 pages to the campaign of 1812 and 50 pages to the campaigns of 1813–1814.[113] Lieven noted that Tolstoy ended War and Peace in December 1812 and that many Russian historians have followed Tolstoy in focusing on the campaign of 1812 while ignoring the greater achievements of campaigns of 1813–1814 that ended with the Russians marching into Paris.[113]

Napoleon did not touch serfdom in Russia. What the reaction of the Russian peasantry would have been if he had lived up to the traditions of the French Revolution, bringing liberty to the serfs, is an intriguing question[118]

Aftermath

The Russian victory over the French Army in 1812 was a significant blow to Napoleon's ambitions of European dominance. This war was the reason the other coalition allies triumphed once and for all over Napoleon. His army was shattered and morale was low, both for French troops still in Russia, fighting battles just before the campaign ended and for the troops on other fronts. Out of an original force of 615,000, only 110,000 frostbitten and half-starved survivors stumbled back into France.[119] The Russian campaign was decisive for the Napoleonic Wars and led to Napoleon's defeat and exile on the island of Elba.[1] For Russia the term Patriotic War (an English rendition of the Russian Отечественная война) became a symbol for a strengthened national identity that had a great effect on Russian patriotism in the 19th century. The indirect result of the patriotic movement of Russians was a strong desire for the modernization of the country that resulted in a series of revolutions, starting with the Decembrist revolt of 1825 and ending with the February Revolution of 1917.

Napoleon was not completely defeated by the disaster in Russia. The following year he raised an army of around 400,000 French troops supported by a quarter of a million allied troops to contest control of Germany in the larger campaign of the Sixth Coalition. Although outnumbered, he won a large victory at the Battle of Dresden. Napoleon could replace the men he lost in 1812, but the huge numbers of horses he lost in Russia proved more difficult to replace, and this proved a major problem in his campaigns in Germany in 1813.[120] It was not until the decisive Battle of Nations (October 16–19, 1813) that he was finally defeated and afterward no longer had the troops to stop the Coalition's invasion of France. Napoleon did still manage to inflict many losses in the Six Days Campaign and a series of minor military victories on the far larger Allied armies as they drove towards Paris, though they captured the city and forced him to abdicate in 1814.

The Russian campaign revealed that Napoleon was not invincible and diminished his reputation as a military genius. Napoleon made many terrible errors in this campaign, the worst of which was to undertake it in the first place. The conflict in Spain was an additional drain on resources and made it more difficult to recover from the retreat. F. G. Hourtoulle wrote "One does not make war on two fronts, especially so far apart".[121] In trying to have both he gave up any chance of success at either. Napoleon had foreseen what it would mean, so he fled back to France quickly before word of the disaster became widespread, allowing him to start raising another army.[119] Following the campaign Metternich began to take the actions that took Austria out of the war with a secret truce.[122] Sensing this and urged on by Prussian nationalists and Russian commanders, German nationalists revolted in the Confederation of the Rhine and Prussia. The decisive German campaign might not have occurred without the defeat in Russia.

Historical echoes

Swedish invasion

Napoleon's invasion was prefigured by the Swedish invasion of Russia a century before. In 1707 Charles XII had led Swedish forces in an invasion of Russia from his base in Poland. After initial success, the Swedish Army was decisively defeated in Ukraine at the Battle of Poltava. Peter I's efforts to deprive the invading forces of supplies by adopting a scorched-earth policy is thought to have played a role in the defeat of the Swedes.

In one first-hand account of the French invasion, Philippe Paul, Comte de Ségur, attached to the personal staff of Napoleon and the author of Histoire de Napoléon et de la grande armée pendant l'année 1812, recounted a Russian emissary approaching the French headquarters early in the campaign. When he was questioned on what Russia expected, his curt reply was simply 'Poltava!'.[123] Using eyewitness accounts, historian Paul Britten Austin described how Napoleon studied the History of Charles XII during the invasion.[124] In an entry dated 5 December 1812, one eyewitness records: "Cesare de Laugier, as he trudges on along the 'good road' that leads to Smorgoni, is struck by 'some birds falling from frozen trees', a phenomenon which had even impressed Charles XII's Swedish soldiers a century ago." The failed Swedish invasion is widely believed to have been the beginning of Sweden's decline as a great power, and the rise of Tsardom of Russia as it took its place as the leading nation of north-eastern Europe.

German invasion

Academicians have drawn parallels between the French invasion of Russia and Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of 1941. David Stahel writes:[125]

Historical comparisons reveal that many fundamental points that denote Hitler's failure in 1941 were actually foreshadowed in past campaigns. The most obvious example is Napoleon's ill-fated invasion of Russia in 1812. The German High Command's inability to grasp some of the essential hallmarks of this military calamity highlights another angle of their flawed conceptualization and planning in anticipation of Operation Barbarossa. Like Hitler, Napoleon was the conqueror of Europe and foresaw his war on Russia as the key to forcing England to make terms. Napoleon invaded with the intention of ending the war in a short campaign centred on a decisive battle in western Russia. As the Russians withdrew, Napoleon's supply lines grew and his strength was in decline from week to week. The poor roads and harsh environment took a deadly toll on both horses and men, while politically Russia's oppressed serfs remained, for the most part, loyal to the aristocracy. Worse still, while Napoleon defeated the Russian Army at Smolensk and Borodino, it did not produce a decisive result for the French and each time left Napoleon with the dilemma of either retreating or pushing deeper into Russia. Neither was really an acceptable option, the retreat politically and the advance militarily, but in each instance, Napoleon opted for the latter. In doing so the French emperor outdid even Hitler and successfully took the Russian capital in September 1812, but it counted for little when the Russians simply refused to acknowledge defeat and prepared to fight on through the winter. By the time Napoleon left Moscow to begin his infamous retreat, the Russian campaign was doomed.

The invasion by Germany was called the Great Patriotic War by the Soviet people, to evoke comparisons with the victory by Tsar Alexander I over Napoleon's invading army.[126] In addition, the French, like the Germans, took solace from the myth that they had been defeated by the Russian winter, rather than the Russians themselves or their own mistakes.[127]

Cultural impact

An event of epic proportions and momentous importance for European history, the French invasion of Russia has been the subject of much discussion among historians. The campaign's sustained role in Russian culture may be seen in Tolstoy's War and Peace, Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture, and the identification of it with the German invasion of 1941–45, which became known as the Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union.

See also

- Antony's Parthian War, a Roman invasion of the Iranian world, which is widely compared to Napoleon's invasion of Russia

- Arches of Triumph in Novocherkassk, a monument built in 1817 to commemorate the victory over the French

- Nadezhda Durova

- General Confederation of Kingdom of Poland

- Vasilisa Kozhina

- List of In Our Time programmes, including "Napoleon's retreat from Moscow"

- List of wars

- Operation Barbarossa

- War and Peace (opera), an opera by Prokofiev

Notes

- von Clausewitz, Carl (1996). The Russian campaign of 1812. Transaction Publishers. Introduction by Gérard Chaliand, VII. ISBN 1-4128-0599-6

- Fierro; Palluel-Guillard; Tulard, p. 159–61

- Riehn 1991, p. 50.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 162.

- Mikaberidze 2016, p. 273.

- Riehn 1991, p. 90.

- Riehn 1991, p. 89.

- Zamoyski 2005, p. 536 — note this includes deaths of prisoners during captivity.

- The Wordsworth Pocket Encyclopedia, p. 17, Hertfordshire 1993.

- Bodart 1916, p. 127.

- The Wordsworth Pocket Encyclopedia, page 17, Hertfordshire 1993.

- http://www.museum.ru/museum/1812/Library/tarle1/tarle1.txt

- Bogdanovich, "History of Patriotic War 1812", Spt., 1859–1860, Appendix, pp. 492–503.

- Bodart 1916, p. 128.

- Zamoyski 2004, p. 536.

- Boudon Jacques-Olivier, Napoléon et la campagne de Russie: 1812, Armand Colin, 2012.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 9.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 294.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 161.

- Caulaincourt 2005, pp. 74–76.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 85, "Everyone was taken aback, the Emperor as well as his men – though he affected to turn the novel method of warfare into a matter of ridicule.".

- Riehn 1991, p. 236.

- The Wordsworth Pocket Encyclopedia, page 17, Hertfordshire 1993.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 268.

- Fierro; Palluel-Guillard; Tulard, p. 159–61.

- Illustrated History of Europe: A Unique Guide to Europe's Common Heritage (1992) p. 282

- McLynn, Frank, pp. 490–520.

- Riehn 1991, pp. 10–20.

- Riehn 1991, p. 25.

- Dariusz Nawrot, Litwa i Napoleon w 1812 roku, Katowice 2008, pp. 58–59.

- Chandler, David (2009). The Campaigns of Napoleon. Simon and Schuster. p. 739. ISBN 9781439131039.

- Riehn 1991, p. 24.

- Riehn 1991, pp. 138–40.

- Mikaberidze 2016, p. 270.

- Elting 1997, p. 566.

- Mikaberidze 2016, p. 271–272.

- Riehn 1991, p. 150.

- Riehn 1991, pp. 139.

- Riehn 1991, p. 169.

- Riehn 1991, pp. 139–53.

- Professor Saul David (9 February 2012). "Napoleon's failure: For the want of a winter horseshoe". BBC news magazine. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- Mikaberidze 2016, p. 271.

- Elting 1997, p. 567.

- Mikaberidze 2016, p. 272.

- Elting 1997, p. 569.

- Mikaberidze 2016, p. 280.

- Mikaberidze 2016, p. 313.

- Elting 1997, p. 570.

- Mikaberidze 2016, p. 278.

- Riehn 1991, p. 151.

- Zamoyski 2005, p. 536 — note this includes deaths of prisoners during captivity.

- Anthony James Joes. "Continuity and Change in Guerrilla War: The Spanish and Afghan Cases", Journal of Conflict Studies Vol. XVI No. 2, Fall 1997. Footnote 27, cites

- Georges Lefebvre, Napoleon from Tilsit to Waterloo (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969), vol. II, pp. 311–12.

- Felix Markham, Napoleon (New York: Mentor, 1963), pp. 190, 199.

- James Marshall-Cornwall: Napoleon as Military Commander (London: Batsford, 1967), p. 220.

- Eugene Tarle: Napoleon's Invasion of Russia 1812 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1942), p. 397.

- Riehn 1991, pp. 77, 501

- Discussed at length in Edward Tufte, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (London: Graphics Press, 1992)

- Lieven 2010, p. 23.

- Helmert/Usczek: Europäische Befreiungskriege 1808 bis 1814/15, Berlin 1986

- Riehn 1991, p. 159.

- Riehn 1991, p. 160.

- Riehn 1991, p. 163.

- Riehn 1991, p. 164.

- Riehn 1991, pp. 160–161.

- Riehn 1991, p. 162.

- Riehn 1991, p. 166.

- Riehn 1991, p. 167.

- Riehn 1991, p. 168.

- Riehn 1991, p. 170.

- Riehn 1991, p. 171.

- Riehn 1991, p. 172.

- Riehn 1991, pp. 174–175.

- Riehn 1991, p. 176.

- Riehn 1991, p. 179.

- Riehn 1991, p. 180.

- Riehn 1991, pp. 182–184.

- Riehn 1991, p. 185.

- George Nafziger, Napoleon's Invasion of Russia (1984) ISBN 0-88254-681-3

- George Nafziger, "Rear services and foraging in the 1812 campaign: Reasons of Napoleon's defeat" (Russian translation online)

- Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Bd. 26, Leipzig 1888 (in German)

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 77, "Before a month is out we shall be in Moscow. In six weeks we shall have peace.".

- August 26 in the Julian calendar then used in Russia.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2007). The Battle of Borodino: Napoleon Against Kutuzov. London: Pen & Sword. pp. 217. ISBN 978-1-84884-404-9.

- Riehn 1991, p. 260.

- Riehn 1991, p. 253.

- Riehn 1991, pp. 255–256.

- Riehn 1991, p. 261.

- Riehn 1991, p. 262.

- Riehn 1991, p. 265.

- Zamoyski 2005, p. 297.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 114.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 121.

- Ten Years' Exile, p. 350-352

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 118.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 119.

- Riehn 1991, p. 300-301.

- "Napoleon-1812". napoleon-1812.nl. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Zamoyski 2004, p. 537.

- Mark Edward Hay. "The Dutch Experience and Memory of the Campaign of 1812: a Final Feat of Arms of the Dutch Imperial Contingent, or: the Resurrection of an Independent Dutch Armed Forces?". academia.edu. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 155.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 259.

- Мороз ли истребил французскую армию в 1812 году? Денис Васильевич Давыдов Archived March 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (Did the cold exterminate the French army in 1812?) by Denis Vasilyevich Davidov in Дневник партизанских действий (Journal of Partisan Actions), part III (in Russian)

- "Fighting the Russians in Winter: Three Case Studies". US Army Command and General Staff College. Archived from the original on June 13, 2006. Retrieved March 31, 2006.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 191.

- Caulaincourt 2005, p. 213, "Our situation was such that one is forced to question whether it is really worthwhile to rally-in wretches whom we could not feed!".

- Allen, Brian M. (1998). The Effects of Infectious Disease on Napoleon's Russian Campaign. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air Command and Staff College. pp. Abstract, v. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.842.4588.

- Riehn 1991, p. 231.

- Grant, R. G. (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 212–13. ISBN 978-0-7566-1360-0.

- Lieven 2010, p. 4-13.

- Lieven 2010, p. 4-5.

- Lieven 2010, p. 5.

- Lieven 2010, p. 5-6.

- Lieven 2010, p. 6.

- Lieven 2010, p. 8.

- Lieven 2010, p. 9.

- Lieven 2010, p. 6-7.

- Lieven 2010, p. 10.

- Lieven 2010, p. 9-10.

- Lieven 2010, p. 11.

- Lieven 2010, p. 11-12.

- Lieven 2010, p. 12.

- Lazar Volin (1970) A century of Russian agriculture. From Alexander II to Khrushchev, p. 25. Harvard University Press

- Riehn 1991, p. 395.

- Lieven 2010, p. 7.

- Hourtoulle 2001, p. 119.

- Riehn 1991, p. 397.

- de Ségur, P.P. (2009). Defeat: Napoleon's Russian Campaign. NYRB Classics. ISBN 978-1-59017-282-7.

- Austin, P.B. (1996). 1812: The Great Retreat. Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-246-0.

- Stahel 2010, p. 448.

- Stahel 2010, p. 337.

- Stahel 2010, p. 30.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to French invasion of Russia. |

- Bodart, G. (1916). Losses of Life in Modern Wars, Austria-Hungary; France. ISBN 978-1371465520.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caulaincourt, Armand-Augustin-Louis (1935), With Napoleon in Russia (translated by Jean Hanoteau ed.), New York: Morrow

- Caulaincourt, Armand-Augustin-Louis (2005), With Napoleon in Russia (translated by Jean Hanoteau ed.), Mineola, New York: Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-44013-2

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elting, J. (1997) [1988]. Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon's Grande Armée. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80757-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hourtoulle, F. G. (2001), Borodino, The Moscova: The Battle for the Redoubts (Hardcover ed.), Paris: Histoire & Collections, ISBN 978-2908182965

- Lieven, Dominic (2010), Russia Against Napoleon The True Story of the Campaigns of War and Peace, New York: Viking, ISBN 978-0670-02157-4

- Mikaberidze, A. (2016). Leggiere, M. (ed.). Napoleon and the Operational Art of War. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-27034-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riehn, Richard K. (1991), 1812: Napoleon's Russian Campaign (Paperback ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 978-0471543022

- Stahel, David (2010). Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East (Third Printing ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76847-4.

- Zamoyski, Adam (2004), Moscow 1812: Napoleon's Fatal March, London: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-00-712375-9

- Zamoyski, Adam (2005), 1812: Napoleon's Fatal March on Moscow, London: Harper Perennial, ISBN 978-0-00-712374-2

Further reading

- Fierro, Alfred; Palluel-Guillard, André; Tulard, Jean (1995), Histoire et Dictionnaire du Consulat et de l'Empire, Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, p. 1350, ISBN 978-2-221-05858-9

- Hay, Mark Edward, The Dutch Experience and Memory of the Campaign of 1812

- Joes, Anthony James (1996), "Continuity and Change in Guerrilla War: The Spanish and Afghan Cases", Journal of Conflict Studies, 16 (2)

- Lieven, Dominic (2009), Russia Against Napoleon: The Battle for Europe, 1807 to 1814, Allen Lane/The Penguin Press, p. 617)review)

- Marshall-Cornwall, James (1967), Napoleon as Military Commander, London: Batsford

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2007), The Battle of Borodino: Napoleon versus Kutuzov, London: Pen&Sword

- Nafziger, George, Rear services and foraging in the 1812 campaign: Reasons of Napoleon's defeat (Russian translation online)

- Nafziger, George (1984), Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, New York, N.Y.: Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0-88254-681-0

- Ségur, Philippe Paul, comte de (2008), Defeat: Napoleon's Russian Campaign, New York: NYRB Classics, ISBN 978-1590172827

Russian studies

- Bogdanovich Modest I. (1859–1860). 'History of the War of 1812' (История Отечественной войны 1812 года) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

Primary sources

- Austin, Paul Britten (1996), 1812: The Great Retreat: told by Survivors

- Brett-James, Antony (1967), 1812: Eyewitness accounts of Napoleon's defeat in Russia