Eritrean War of Independence

The Eritrean War of Independence was a conflict fought between the Ethiopian government and Eritrean separatists from September 1961 to May 1991.

| Eritrean War of Independence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ethiopian Civil War, the Cold War and the conflicts in the Horn of Africa | |||||||||

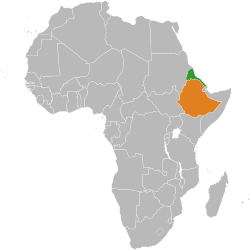

Military situation during the Eritrean War of Independence | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by:

|

1961–1974 Supported by:

1974–1991 Supported by:

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

60,000 insurgents[32] 90,000 civilians[32] | |||||||||

Eritrea was claimed by the Ethiopian Empire from 1947 after Eritrea was liberated from Italy's occupation since 1890 (both countries were part of Italian East Africa during World War II). Ethiopia and some of the predominantly Christian parts of Eritrea advocated for a union with Ethiopia, while predominantly Muslim and other areas of Eritrea wanted a separate Eritrean state. The United Nations General Assembly in an effort to satisfy both sides decided to federate Eritrea with Ethiopia in 1950, and Eritrea became a constituent state of the Federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea in 1952.[33] Eritrea's declining autonomy and growing discontent with Ethiopian rule caused an independence movement led by the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) in 1961, leading Ethiopia to dissolve the federation and annex Eritrea the next year.

Following the Ethiopian Revolution in 1974, the Derg abolished the Ethiopian Empire and established a Marxist-Leninist communist state, bringing the Eritrean War of Independence into the Ethiopian Civil War and Cold War conflicts. The Derg enjoyed support from the Soviet Union and other Second World nations in fighting against Eritrean separatists supported by the United States and various other nations. The Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) became the main separatist group in 1977, expelling the ELF from Eritrea, then exploiting the Ogaden War to launch a war of attrition against Ethiopia. The Ethiopian government under the Workers Party of Ethiopia lost Soviet support at the end of the 1980s and were overwhelmed by Eritrean separatists and Ethiopian anti-government groups, allowing the EPLF to defeat Ethiopian forces in Eritrea in May 1991.[34]

The Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), with the help of the EPLF, defeated the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE) when it took control of the capital Addis Ababa a month later.[35] In April 1993, the Eritrean people voted almost unanimously in favour of independence in the Ethiopia-supported Eritrean independence referendum, with formal international recognition of an independent, sovereign Eritrea later the same year.

Background

The Italians colonised Eritrea in 1890. In 1936, Italy invaded Ethiopia and declared it part of their colonial empire, which they called Italian East Africa. Italian Somaliland was also part of that entity. There was a unified Italian administration.

Conquered by the Allies in 1941, Italian East Africa was sub-divided. Ethiopia reoccupied its formerly Italian occupied lands in 1941. Italian Somaliland remained under Italian rule until 1960 but as a United Nations protectorate, not a colony, when it united with independence in 1960, to form the independent state of Somalia.

Eritrea was made a British Protectorate from the end of World War II until 1951. However, there was debate as to what should happen with Eritrea after the British left. The British proposed that Eritrea be divided along religious lines with the Christians to Ethiopia and the Muslims to Sudan. This, however, caused great controversy. Then, in 1952, the UN decided to federate Eritrea to Ethiopia, hoping to reconcile Ethiopian claims of sovereignty and Eritrean aspirations for independence. About nine years later, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie dissolved the federation and annexed Eritrea, triggering a thirty-year armed struggle in Eritrea.[36]

Revolution

During the 1960s, the Eritrean independence struggle was led by the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF). The independence struggle can properly be understood as the resistance to the annexation of Eritrea by Ethiopia long after the Italians left the territory. Additionally, one may consider the actions of the Ethiopian Monarchy against Muslims in the Eritrean government as a contributing factor to the revolution.[37] At first, this group factionalized the liberation movement along ethnic and geographic lines. The initial four zonal commands of the ELF were all lowland areas and primarily Muslim. Few Christians joined the organization in the beginning, fearing Muslim domination.[38]

After growing disenfranchisement with Ethiopian occupation, highland Christians began joining the ELF. Typically these Christians were part of the upper class or university-educated. This growing influx of Christian volunteers prompted the opening of the fifth (highland Christian) command. Internal struggles within the ELF command coupled with sectarian violence among the various zonal groups splintered the organization.

The war started on 1 September 1961 with the Battle of Adal, when Hamid Idris Awate and his companions fired the first shots against the occupying Ethiopian Army and police. In 1962, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia unilaterally dissolved the federation and the Eritrean parliament and annexed the country.

War (1961–1991)

In 1970 members of the group had a falling out, and several different groups broke away from the ELF. During this time, the ELF and the groups that later joined together to form the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) fought a bitter civil war. The two organizations were forced by popular will to reconcile in 1974 and participated in joint operations against Ethiopia.

In 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie was ousted in a coup. The new Ethiopian government, called the Derg, was a Marxist military junta, which eventually came to be controlled by strongman Mengistu Haile Mariam. The new Derg regime took an additional three to four years to get complete control of both Ethiopia, Eritrea, and parts of Somalia. With this change of government and eventually widely known recognition, Ethiopia became directly under the influence of the Soviet Union.

Many of the groups that splintered from the ELF joined together in 1977 and formed the EPLF. By the late 1970s, the EPLF had become the dominant armed Eritrean group fighting against the Ethiopian government. The leader of the umbrella organization was Secretary-General of the EPLF Ramadan Mohammed Nour, while the Assistant Secretary-General was Isaias Afewerki.[39] Much of the equipment used to combat Ethiopia was captured from the Ethiopian Army.

During this time, the Derg could not control the population by force alone. To supplement its garrisons, forces were sent on missions to instill fear in the population. An illustrative example of this policy was the village of Basik Dera in northern Eritrea. On 17 November 1970, the entire village was rounded up into the local mosque and the mosque's doors were locked. The building was then razed and the survivors were shot . Similar massacres took place in primarily Muslim parts of Eritrea, including the villages of She'eb, Hirgigo, Elabared, and the town of Om Hajer; massacres also took place in predominately Christian areas as well.[38] The advent of these brutal killings of civilians regardless of race, religion, or class was the final straw for many Eritreans who were not involved in the war, and at this point many either fled the country or went to the front lines.[40]

From 1975 to 1977, the ELF and EPLF outnumbered the Ethiopian army and overran all of Eritrea except Asmara, Massawa, and Barentu.[41] By 1977, the EPLF was poised to drive the Ethiopians out of Eritrea, by utilizing a simultaneous military offensive from the east by Somalia to siphon off Ethiopian military resources. The Somali invasion surprised many experts in the west due to the initial successes, however the Soviet Union, Cuba and Yemen came to the government's aid allowing them to prevent the Somalis from coming to the capital. This turnaround was possible thanks mainly to a massive airlift of Soviet arms, the deployment of 18,000 Cubans and two Yemeni brigades to reinforce Harar. After that, using the considerable manpower and military hardware available from the Somali campaign, the Ethiopian Army regained the initiative and forced the EPLF to retreat to the bush. This was most notable in the Battle of Barentu and the Battle of Massawa.

Between 1978 and 1986, the Derg launched eight major offensives against the independence movements, and all failed to crush the guerrilla movement. In 1988, with the Battle of Afabet, the EPLF captured Afabet and its surroundings, then headquarters of the Ethiopian Army in northeastern Eritrea, prompting the Ethiopian Army to withdraw from its garrisons in Eritrea's western lowlands. EPLF fighters then moved into position around Keren, Eritrea's second-largest city. Meanwhile, other dissident movements were making headway throughout Ethiopia.

Throughout the conflict Ethiopia used "anti-personnel gas",[42] napalm,[43] and other incendiary devices.

At the end of the 1980s, the Soviet Union informed Mengistu that it would not be renewing its defence and cooperation agreement. With the cessation of Soviet support and supplies, the Ethiopian Army's morale plummeted, and the EPLF, along with other Ethiopian rebel forces, began to advance on Ethiopian positions. The joint effort to overthrow the Mengistu, Marxist regime was a joint effort of mostly EPLF forces, united with other Ethiopian faction groups primarily consisting of tribal liberation fronts (for example: the Oromo Liberation Front, the Tigrayan People's Liberation Front – who were jointly in battles against the ELF and other key battles where many Tigrayans were lost in the Eritrean Civil Wars – and the EPRDF, a conglomerate of the current TPLF regime and the marxist Oromo People's Democratic Organization who became prominent for recruiting Derg defectors as the EPLF and EPRDF occupied parts of the provinces of Wollo and Shewa in Ethiopia).[44]

.svg.png)

Peace talks

The former President of the United States, Jimmy Carter, with the help of some U.S. government officials and United Nation officials, attempted to mediate in peace talks with the EPLF, hosted by the Carter Presidential Center in Atlanta, Georgia in September 1989. Ashagre Yigletu, Deputy Prime Minister of the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE), helped negotiate and signed a November 1989 peace deal with the EPLF in Nairobi, along with Jimmy Carter and Al-Amin Mohamed Seid. However, soon after the deal was signed, hostilities resumed.[7][45][46][47] Yigletu also led the Ethiopian government delegations in peace talks with the TPLF leader Meles Zenawi in November 1989 and March 1990 in Rome.[48][49] He also attempted again to lead the Ethiopian delegation in peace talks with the EPLF in Washington, D.C. until March 1991.[50]

Recognition

After the end of the Cold War, the United States played a facilitative role in the peace talks in Washington, D.C. during the months leading up to the May 1991 fall of the Mengistu regime. In mid-May, Mengistu resigned as head of the Ethiopian government and went into exile in Zimbabwe, leaving a caretaker government in Addis Ababa. A high-level U.S. delegation was present in Addis Ababa for the 1–5 July 1991 conference that established a transitional government in Ethiopia. Having defeated the Ethiopian forces in Eritrea, the EPLF attended as an observer and held talks with the new transitional government regarding Eritrea's relationship to Ethiopia. The outcome of those talks was an agreement in which the Ethiopians recognized the right of the Eritreans to hold a referendum on independence. The referendum was held in April 1993 and the Eritrean people voted almost unanimously in favour of independence, with the integrity of the referendum being verified by the UN Observer Mission to Verify the Referendum in Eritrea (UNOVER). On 28 May 1993, the United Nations formally admitted Eritrea to its membership.[51] Below are the results from the referendum:

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 1,100,260 | 99.83 |

| No | 1,822 | 0.17 |

| Invalid/blank votes | 328 | - |

| Total | 1,102,410 | 100 |

| Registered voters/turnout | 1,173,706 | 98.52 |

| Source: African Elections Database | ||

| Region | Do you want Eritrea to be an independent and sovereign country? | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | uncounted | ||

| Asmara | 128,443 | 144 | 33 | 128,620 |

| Barka | 4,425 | 47 | 0 | 4,472 |

| Denkalia | 25,907 | 91 | 29 | 26,027 |

| Gash-Setit | 73,236 | 270 | 0 | 73,506 |

| Hamasien | 76,654 | 59 | 3 | 76,716 |

| Akkele Guzay | 92,465 | 147 | 22 | 92,634 |

| Sahel | 51,015 | 141 | 31 | 51,187 |

| Semhar | 33,596 | 113 | 41 | 33,750 |

| Seraye | 124,725 | 72 | 12 | 124,809 |

| Senhit | 78,513 | 26 | 1 | 78,540 |

| Freedom fighters | 77,512 | 21 | 46 | 77,579 |

| Sudan | 153,706 | 352 | 0 | 154,058 |

| Ethiopia | 57,466 | 204 | 36 | 57,706 |

| Other | 82,597 | 135 | 74 | 82,806 |

| % | 99.79 | 0.17 | 0.03 | |

References

Notes

- Fauriol, Georges A; Loser, Eva (1990). Cuba: the international dimension. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-88738-324-6.

- The maverick state: Gaddafi and the New World Order, 1996. Page 71.

- Connell, Dan; Killion, Tom (2011). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-5952-4.

- Schoultz, Lars (2009). That infernal little Cuban republic: the United States and the Cuban Revolution. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3260-8.

- Historical Dictionary of Eritrea, 2010. Page 492

- Oil, Power and Politics: Conflict of Asian and African Studies, 1975. Page 97.

- Fontrier, Marc. La chute de la junte militaire ethiopienne: (1987–1991) : chroniques de la Republique Populaire et Democratique d'Ethiopie. Paris [u.a.]: L' Harmattan, 1999. pp. 453–454

- Eritrea: Even the Stones Are Burning, 1998. Page 110

- Eritrea – liberation or capitulation, 1978. Page 103

- Politics and liberation: the Eritrean struggle, 1961–86: an analysis of the political development of the Eritrean liberation struggle 1961–86 by help of a theoretical framework developed for analysing armed national liberation movements, 1987. Page 170

- Tunisia, a Country Study, 1979. Page 220.

- African Freedom Annual, 1978. Page 109

- Ethiopia at Bay: A Personal Account of the Haile Selassie Years, 2006. page 318.

- Historical Dictionary of Eritrea, 2010. page 460

- Spencer C. Tucker, A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, 2009. page 2402

- The Pillage of Sustainablility in Eritrea, 1600s–1990s: Rural Communities and the Creeping Shadows of Hegemony, 1998. Page 82.

- Foreign Intervention in Africa: From the Cold War to the War on Terror, 2013. Page 158.

- Chinese and African Perspectives on China in Africa 2009, Page 93

- Ethiopia and the United States: History, Diplomacy, and Analysis, 2009. page 84.

- [1][2][3][19]

- "Toledo Blade - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- Ethiopia Archived 10 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Peace Corps website (accessed 6 July 2010)

- File:Haille Sellasse and Richard Nixon 1969.png

- [21][22][23]

- "Ethiopia-Israel". country-data.com. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- U.S. Requests for Ethiopian Bases Pushed Toledo Blade, March 13, 1957

- "Communism, African-Style". Time. 4 July 1983. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- "Ethiopia Red Star Over the Horn of Africa". Time. 4 August 1986. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- "Ethiopia a Forgotten War Rages On". Time. 23 December 1985. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- [27][28][29][30]

- Cousin, Tracey L. "Eritrean and Ethiopian Civil War". ICE Case Studies. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- "Eritrea: Report of the United Nations Commission for Eritrea; Report of the Interim Committee of the General Assembly on the Report of the United Nations Commission for Eritrea". undocs.org. United Nations. 2 December 1950. A/RES/390(V). Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Ethiopia-Eritrea: A Troubled Relationship". The Washington Post.

- Krauss, Clifford (28 May 1991). "Ethiopian Rebels Storm the Capital and Seize Control". The New York Times.

- "Ethiopia and Eritrea", Global Policy Forum

- "HISTORY OF ERITREA". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- Killion, Tom (1998). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow. ISBN 0-8108-3437-5.

- "Discourses on Liberation and Democracy – Eritrean Self-Views". Archived from the original on 15 December 2004. Retrieved 25 August 2006.

- "List of massacres committed during the Eritrean War of Independence - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia". www.ehrea.org. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- Waal, Alexander De (1991). Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia. Human Rights Watch. p. 50. ISBN 9781564320384.

- Johnson & Johnson 1981.

- Keller 1992.

- "Ethiopia - Eritrea: A tale of Two Halves". TesfaNews. 21 August 2014.

- AP Images. Former President Jimmy Carter tells a news conference that peace talks between delegations headed by Alamin Mohamed Saiyed, left, of the Eritrean People's Liberation Front and Ashegre Yigletu, right, of the Worker's Party of Ethiopia will be resumed in November in Nairobi, Kenya, at the Carter Presidential Center in Atlanta, Sept. 19, 1989. (AP Photo/Charles Kelly)

- New African. London: IC Magazines Ltd., 1990. p. 9

- The Weekly Review. Nairobi: Stellascope Ltd.], 1989. p. 199

- Haile-Selassie, Teferra. The Ethiopian Revolution, 1974–1991: From a Monarchical Autocracy to a Military Oligarchy. London [u.a.]: Kegan Paul Internat, 1997. p. 293

- countrystudies.us. [Regime Stability and Peace Negotiations]

- Iyob, Ruth. The Eritrean Struggle for Independence: Domination, Resistance, Nationalism, 1941–1993. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1997. p. 175

- "Eritrea". Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

- "Eritrea: Birth of a Nation". Retrieved 30 January 2007.

Bibliography

- Gebru Tareke (2009). The Ethiopian Revolution: War in the Horn of Africa. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14163-4.

- Johnson, Michael; Johnson, Trish (1981). "Eritrea: The National Question and the Logic of Protracted Struggle". African Affairs. 80: 181–195. JSTOR 721320.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keller, Edmond J. (1992). "Drought, War, and the Politics of Famine in Ethiopia and Eritrea". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 30 (4): 609–624. doi:10.1017/s0022278x00011071. JSTOR 161267.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eritrean War of Independence. |

.svg.png)