Russo-Turkish War (1828–29)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 was sparked by the Greek War of Independence of 1821–1829. War broke out after the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II closed the Dardanelles to Russian ships and revoked the 1826 Akkerman Convention in retaliation for Russian participation in October 1827 in the Battle of Navarino.[2]

| Russo-Turkish War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Russo-Turkish Wars, Russian conquest of the Caucasus, and Greek War of Independence | |||||||||

Battle of Akhalzic (1828), by January Suchodolski. Oil on canvas, 1839 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 100,000[1] | Unknown | ||||||||

Opening hostilities

At the start of hostilities the Russian army of 100,000 men was commanded by Emperor Nicholas I, while the Ottoman forces were commanded by Hussein Pasha. In April and May 1828 the Russian commander-in-chief, Prince Peter Wittgenstein, moved into Romanian Principates Wallachia and Moldavia. In June 1828, the main Russian forces under the emperor crossed the Danube and advanced into Dobruja.

The Russians then laid prolonged sieges to three key Ottoman citadels in modern Bulgaria: Shumla, Varna, and Silistra.[1] With the support of the Black Sea Fleet under Aleksey Greig, Varna was captured on 29 September. The siege of Shumla proved much more problematic, as the 40,000-strong Ottoman garrison outnumbered the Russian forces. As the latter were harassed by Turkish troops and ill-equipped, many of its soldiers died of disease or exhaustion. Russia then had to withdraw to Moldavia with heavy losses without having captured Shumla and Silistra.[3]

Changing fortunes

As winter approached, the Russian army was forced to leave Shumla and retreat back to Bessarabia. In February 1829 the cautious Wittgenstein was replaced by the more energetic Hans Karl von Diebitsch, and the Tsar left the army for St Petersburg. On 7 May, 60,000 soldiers led by Field Marshal Diebitsch crossed the Danube and resumed the siege of Silistra. The Sultan sent a 40,000-strong contingent to the relief of Varna, which was defeated at the Battle of Kulevicha on 30 May. Three weeks later on 19 June, Silistra fell to the Russians.

Meanwhile, Ivan Paskevich advanced on the Caucasian front defeated the Turks at the Battle of Akhalzic and captured Kars on 23 June and Erzurum, in north-eastern Anatolia on 27 June, the 120th anniversary of the Poltava.

On 2 July Diebitsch launched the Transbalkan offensive, the first in Russian history since the 10th-century campaigns of Svyatoslav I. The contingent of 35,000 Russians moved across the mountains, circumventing the besieged Shumla on their way to Constantinople. The Russians captured Burgas ten days later, and the Turkish reinforcement was routed near Sliven on 31 July. By 22 August, the Russians had taken Adrianople,[4] reportedly causing the Muslim population in the city to leave.[5] The Ottoman palace in Adrianople, Saray-i Djedid-i Amare, was heavily damaged by Russian troops.[5]

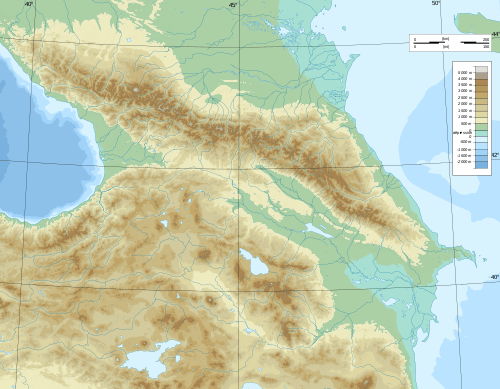

Caucasus front

Although the main fighting was in the west there was significant action on the Caucasus front. Paskevich’s main aims were to tie down as many Turkish troops as possible, to capture the Turkish forts on the Black Sea coast that supported the Circassians and might be used to land troops, and to push the border west to some desirable point. Most of the Turkish side was held by the semi-independent Pasha of Akhaltsikhe and Muslim Georgian Beys who ruled the hills. Kars on an upland plain blocked the road from Akhaltsikhe to Erzerum, the main city in eastern Turkey. The Russo-Persian War (1826–28) had just ended, which removed a major danger. Since two-thirds of his troops were tied down holding the Caucasus and watching the Persians, he had only 15.000 men to fight the Turks. The Turks delayed attacking so he had time to move troops and supplies west, concentrating at Gyumri on the border.

1828, June: Kars: On 14 June[6] he set out for Kars 40 miles southwest which was held by 11.000 men and 151 guns. The capture of Kars was almost an accident. During a skirmish in the suburbs a company of riflemen under Lieutenant Labintsev made an unauthorized advance. Seeing their danger other companies rushed to the rescue. Their danger drew in more soldiers until most of the Russian force was massed at one point. The wall was breached and soon the Turks held only the citadel. At 10AM 23 June the citadel surrendered. The Turks lost 2.000 killed and wounded, 1350 prisoners and 151 guns, but much of the garrison managed to escape. The Russians lost 400 killed and wounded. Kios Pasha[7] of Erzerum was within an hour’s march of Kars, but when he heard the news he withdrew to Ardahan.

1828, July: Akhalkalaki: Paskevich feinted toward Erzerum and then marched north to Akhalkalaki. Under bombardment, the 1000-man garrison became demoralized and half of them tried to escape by letting themselves down the walls on ropes, but most were killed. The Russians used the same ropes to scale the walls and the remaining 300 men surrendered (24 July).

1828, August: Akhaltsikhe: Forty miles west was Akhaltsikhe with 10.000 men under its semi-independent Pasha. It guarded the Borjomi Gorge which led northeast to Georgia. Instead of taking the main road which went southwest to Ardahan and then north, Paskevich and 8000 men marched three days through roadless country and reached Akhaltsikhe on 3 August. The next day Kios Pasha and 30.000 men encamped four miles from the fort. Paskevich, outnumbered by an enemy on two sides, turned on Kios. After a day-long battle Kios, wounded, and 5.000 infantry fled to the fort and the remaining Turks scattered south to Ardahan. The Russians took enormous booty and lost 531 men, including a general. The siege now began. Akhaltsikhe had three lines of defense: the fortress, the citadel within and the town without. The town, with its crooked streets, ravines and bastions was almost a fortress itself. The attack began at 4PM, the citizens defended themselves as best they could and by nightfall the town was on fire. In one mosque 400 people burned to death. By dawn of the 16th the ruined town was in Russian hands. They moved artillery up to bear on the fortress walls. On 17 August Kios Pasha surrendered on the condition that he and 4000 men be allowed to withdraw with their arms and property. The Russians lost about 600 men and the Turks 6000. The next day they took the Atskhur castle which controlled the Borjomi Gorge leading from Akhaltsikhe northeast to Georgia. On 22 August the occupied Ardahan, the road junction connecting Akhaltsikhe-Akhalkalaki to the Kars-Erzerum road. Seeing no further opportunities the Russians retired to winter quarters.

On the Black Sea coast Anapa was captured on 12 June and Poti on 15 June. By September Chavchadvadze had occupied the Pashalik of Bayazid with little opposition. “And the banners of your majesty float over the headwaters of the Euphrates.” On the last day of September the Russians occupied Guria.

X=Russian

Blue circle=Taken and returned; Blue triangle=Turkish not captured

1829: Kios Pasha was replaced by Salih Pasha with Haghki (Hakki) Pasha as his deputy. In winter Paskevich went to St Petersburg with a plan for a massive invasion of Anatolia, but this was rejected. 20000 raw recruits would be sent to the Caucasus, but they would not be ready until late summer. On 30 January the Russian ambassadors to Tehran, including Alexander Griboyedov were killed by a mob. Both sides were too wise to start another war but the possibility tied up part of the Russian army. On 21 February Akhmet Beg (Ahmet Bey) of Hulo and 15000 Lazes and Adjars occupied the town of Akhaltsikhe, slaughtered the Armenian part of the population, and besieged the fortress. Twelve days later Burtsev forced the Borjomi Gorge and the Adjars fled with their loot. General Hesse drove back a Turkish advance from Batum and captured the Turkish camp of Limani south of Poti. Far to the southeast, Bayazid was besieged by the Pasha of Van. The main Turkish advance began in mid-May. Kiaghi Bek approached Ardahan, but was driven north to Adjaria where he threatened Akhaltsikhe. He was defeated at Digur south of Akhaltsikhe and the Russians went south to join Paskevich at Kars.

1829, June: Saganlug and Erzerum: On 13 June Paskevich (12340 infantry, 5785 cavalry and 70 guns) left Kars for Erzerum. The Turks had 50000 men including 30000 nizams (new-model infantry). They stood between Hasankale and Zivin on the Erzerum-Kars road. Further east on the road an advanced force (20000 under Haghki Pasha) held the Millidiuz (Meliduz) Pass over the Saganlug[8] mountain. Paskevich chose to take the inferior road to the north, place himself near Zevin between the two armies and attack Haghki Pasha from the rear. There were complex maneuvers and small actions. At 7 PM on the 19th Paskevich attacked and completely defeated the western army. Next day he turned east and captured Haghki Pasha and 19 guns, but most of his men managed to scatter. With the armies out of the way he set out for Erzerum. On 27 June that great city, which had not seen Christian soldiers within its walls for five centuries, surrendered, due, it is said to the cowardice of its citizens.

1829: After Erzerum: From Erzerum the main road led northwest through Bayburt and Hart to Trebizond on the coast, a very formidable place that could only be taken with the fleet which was now busy on the Bulgarian coast. In July Burtsev went up this road and was killed at Hart. To retrieve Russia’s reputation Paskevich destroyed Hart (28 July). He sent an army somewhere west and brought it back, went up the Trebizond road, saw that nothing could be accomplished in that direction, and returned to Erzerum. Hesse and Osten-Sacken pushed north toward Batum and returned. The Pasha of Trebizond moved against Bayburt and was defeated on 28 September, the last action of the war. The Treaty of Adrianople (1829) was signed on 2 September 1829, but it took a month for the news to reach Paskevich. In October his army began marching home. Russia kept the ports of Anapa and Poti, the border forts of Atskhur, Akhalkalaki and Akhaltsikhe fort, but returned Ardahan and the Pashaliks of Kars, Bayazid and most of Akhaltsikhe Pashalik. In 1855 and 1877 Paskevich’s work had to be done all over again. One consequence of the war the migration of 90000 Armenians from Turkish to Russian territory.

The Treaty of Adrianople

Faced with these several defeats, the Sultan decided to sue for peace. The Treaty of Adrianople on 14 September 1829 gave Russia most of the eastern shore of the Black Sea and the mouth of the Danube. Turkey recognized Russian sovereignty over parts of northwest present-day Armenia. Serbia achieved autonomy and Russia was allowed to occupy Moldavia and Wallachia (guaranteeing their prosperity and full "liberty of trade") until Turkey had paid a large indemnity. Moldavia and Wallachia remained Russian protectorates until the Crimean War. The Straits Question was settled four years later, when both powers signed the Treaty of Hünkâr İskelesi.

Regarding the Greek case, with the treaty of Andrianople, the Ottoman Sultan recognized finally the autonomy or independence of the Greeks. Much later, Karl Marx in an article in New York Tribune (21 April 1853), wrote: "Who solved finally the Greek case? It was neither the rebellion of Ali Pasha, neither the battle in Navarino, neither the French Army in Peloponnese, neither the conferences and protocols of London; but it was Diebitsch, who invaded through the Balkans to Evros."[9]

See also

- Russo-Persian War (1826–28)

- Greek War of Independence

Sources and further reading

- Bitis, Alexander. "The 1828–1829 Russo-Turkish war and the resettlement of Balkan peoples into Novorossiia." Jahrbücher Für Geschichte Osteuropas (2005): 506-525 online in English

- William Edward David Allen and Muratoff, Paul, Caucasian Battlefields, 1953,2010, Chapter II

- Michael Khodarkovsky. Bitter Choices: Loyalty and Betrayal in the Russian Conquest of the North Caucasus (Cornell University Press, 2011). excerpt

- J. A. R. Marriott, The Eastern Question An Historical Study In European Diplomacy (1940) pp 221–225. online

In Russian

- (in Russian) Османская империя: проблемы внешней политики и отношений с Россией. М., 1996.

- (in Russian) Шишов А.В. Русские генерал-фельдмаршалы Дибич-Забалканский, Паскевич-Эриванский. М., 2001.

- (in Russian) Шеремет В. И. У врат Царьграда. Кампания 1829 года и Адрианопольский мирный договор. Русско-турецкая война 1828–1829 гг.: военные действия и геополитические последствия. – Военно-исторический журнал. 2002, № 2.

References

- A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol.III, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010), 1152.

- Michael Khodarkovsky, Bitter Choices: Loyalty and Betrayal in the Russian Conquest of the North Caucasus (2011).

- Metternich and Austria: An Evaluation, Alan Sked

- Stanford J. Shaw, Ezel Kural Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey:Reform, Revolution, Republic, Volume 2, (Cambridge University Press, 1977), 31.

- Edirne, M. Tayyib Gokbilgin, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. II, ed. B. Lewis, C. Pellat and J. Schacht, (Brill, 1991), 684.

- All dates Old Style so add 12 days for the modern calendar

- Allen-Muratoff call him Köse Mehmet. Köse means beardless so he may have been a eunuch.

- Allen-Muratoff have Soğanli-dağ (former) and Pasinler-sira-dağ(current)

- Μάρξ για Ρωσοτουρκικό

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829). |