Serbian campaign

The Serbian Campaign is the series of campaigns launched against Serbia at the beginning of the First World War. The first campaign began after Austria Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914, the campaign to "punish" Serbia, under the command of Austrian Oskar Potiorek, ended after three unsuccessful Austro-Hungarian invasion attempts were repelled by the Serbs and their Montenegrin allies. Serbia's defeat of the Austro-Hungarian invasion of 1914 ranks as one of the great upsets of modern military history.

| Serbian campaign | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Balkans Theatre of World War I | |||||||||

Serbian infantry positioned at Ada Ciganlija. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Central Powers: |

Allied Powers: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

1914: 1915: |

1914-1915: | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

1914: 1915: |

1914: 1915: | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

1914: Total: 340,000+ battle and non-battle casualties |

1914: Total: 405,000+ battle casualties | ||||||||

| 450,000 Serbian civilians died of war-related causes from 1914 to 1918[13] | |||||||||

The Second Campaign was launched, under German command, almost a year later, on 6 October 1915, when Bulgarian, Austrian, and German forces, lead by Field Marshall August von Mackensen, invaded Serbia from three sides, pre-empting the Allied advance from Salonica to help her. This resulted in the Great Retreat through Montenegro and Albania, the evacuation to Greece and the establishment of the Macedonian front.[14] The defeat of Serbia gave the Central Powers temporary mastery over the Balkans, opening up a land route from Berlin to Istanbul, allowing the Germans to re-supply the Ottoman Empire for the rest of the war.[15] Mackensen declared an end to the campaign on November 24, 1915. Serbia was then divided and occupied by the Habsburg Empire and Bulgaria.[16]

After the Allies launched the Vardar offensive in September 1918, which broke through the Macedonian front and defeated the Bulgarians and their German allies, a Franco-Serbian force advanced into the occupied territories and liberated Serbia, Albania and Montenegro. Serbian forces entered Belgrade on 1 November 1918.[17]

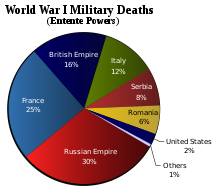

The Serbian Army declined severely from about 420,000[4] at its peak to about 100,000 at the moment of liberation. The estimates of casualties are various: the Serb sources claim that the Kingdom of Serbia lost more than 1,200,000 inhabitants during the war (both army and civilian losses), which represented over 29% of its overall population and 60% of its male population,[18][19] while western historians put the number either at 45,000 military deaths and 650,000 civilian deaths[20] or 127,355 military deaths and 82,000 civilian deaths. According to estimates prepared by the Yugoslav government in 1924, Serbia lost 265,164 soldiers, or 25% of all mobilized people. By comparison, France lost 16.8%, Germany 15.4%, Russia 11.5%, and Italy 10.3%.[21]

Background

Austria-Hungary precipitated the Bosnian crisis of 1908–09 by annexing the former Ottoman territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which it had occupied since 1878. This angered the Kingdom of Serbia and its patron, the Pan-Slavic and Orthodox Russian Empire.[22] Russian political manoeuvring in the region destabilised peace accords that were already unravelling in what was known as "the powder keg of Europe".[22]

In 1912 and 1913, the First Balkan War was fought between the Balkan League of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro and the fracturing Ottoman Empire. The resulting Treaty of London further shrank the Ottoman Empire by creating an independent Principality of Albania and enlarging the territorial holdings of Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece. When Bulgaria attacked both Serbia and Greece on 16 June 1913, it lost most of its Macedonian region to those countries, and additionally the Southern Dobruja region to Romania and Adrianople (the present-day city of Edirne) to Turkey in the 33-day Second Balkan War, which further destabilized the region.[23]

On 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb student and member of a multi-ethnic organisation of national revolutionaries called Young Bosnia, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, in Sarajevo, Bosnia.[24] The political objective of the assassination was the independence of the southern Austro-Hungarian provinces mainly populated by Slavs from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, though it also inadvertently triggered a chain of events that embroiled Russia and the major European powers. This began a period of diplomatic manoeuvring among Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, France, and Britain called the July Crisis. Austria-Hungary delivered the July Ultimatum to Serbia, a series of ten demands intentionally made unacceptable in order to provoke a war with Serbia.[25] When Serbia agreed to only eight of the ten demands, Austria-Hungary declared war on 28 July 1914.

The dispute between Austria-Hungary and Serbia escalated into what is now known as World War I, and drew in Russia, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. Within a week, Austria-Hungary had to face a war with Russia, Serbia's patron, which had the largest army in the world at the time. The result was that Serbia became a subsidiary front in the massive fight that started to unfold along Austria-Hungary's border with Russia. Serbia had an experienced army, but it was also exhausted from the conflicts of the Balkan Wars and poorly equipped, which led the Austro-Hungarians to believe that it would fall in less than a month. Serbia's strategy was to hold on as long as it could and hope the Russians could defeat the main Austro-Hungarian Army, with or without the help of other allies. Serbia constantly had to worry about its hostile neighbor to the east, Bulgaria, with which it had fought several wars, most recently in the Second Balkan War of 1913.

Military forces

Austro-Hungarian

The standing peacetime Austro-Hungarian army had some 36,000 officers and non-commissioned officers and 414,000 enlisted personnel. During the mobilization, this number was increased to a total of 3,350,000 men of all ranks. The operational army had over 1,420,000 men, and a further 600,000 were allocated to support and logistic units (train, munition and supply columns, etc.) while the rest – around 1,350,000 – were reserve troops available for replacing losses and the formation of new units.[26] This vast manpower allowed the Austro-Hungarian army to replace its losses regularly and keep units at their formation strength. According to some sources, during 1914 there were on average 150,000 men per month sent to replace the losses in the field army. During 1915 these numbers rose to 200,000 per month.[27] According to the official Austrian documents in the period from September until the end of December 1914, some 160,000 replacement troops were sent to the Balkan theater of war, as well as 82,000 reinforcements as part of newly formed units.[28]

The pre-war Austro-Hungarian plan for invasion of Serbia envisioned the concentration of three armies (2nd, 5th and 6th) on the western and northern borders of Serbia with the main goal of enveloping and destroying the bulk of the Serbian army. However, with the beginning of the Russian general mobilization, the Armeeoberkommando (AOK, Austro-Hungarian Supreme Command) decided to move the 2nd Army to Galicia to counter Russian forces. Due to the congestion of railroad lines towards Galicia, the 2nd Army could only start its departure on 18 August, which allowed the AOK to assign some units of the 2nd Army to take part in operations in Serbia before that date. Eventually, the AOK allowed General Oskar Potiorek to deploy a significant part of the 2nd Army (around four divisions) in fighting against Serbia, which caused a delay of transport of these troops to the Russian front for more than a week. Furthermore, the Austro-Hungarian defeats suffered during the first invasion of Serbia forced the AOK to transfer two divisions from the 2nd Army permanently to Potiorek's force. By 12 August, Austria-Hungary had amassed over 500,000 soldiers on Serbian frontiers, including some 380,000 operational troops. With the departure of the major part of the 2nd Army to the Russian front, this number fell to some 285,000 of operational troops, including garrisons.[29] Apart from land forces, Austria-Hungary also deployed its Danube River flotilla of six monitors and six patrol boats.

Many Austro-Hungarian soldiers were not of good quality.[30] About one-quarter of them were illiterate, and most of the conscripts from the empire's subject nationalities did not speak or understand German or Hungarian. In addition to this, most of the soldiers — ethnic Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Romanians and South Slavs — had linguistic and cultural links with the empire's various enemies.[31]

Serbian

The Serbian military command issued orders for the mobilization of its armed forces on 25 July and the mobilization began the following day. By 30 July, the mobilization was completed and the troops began to be deployed according to the war plan. Deployments were completed by 9 August, when all of the troops had arrived at their designated strategic positions. During mobilization, Serbia raised approximately 450,000 men of three age-defined classes (or bans) called poziv, which comprised all able-bodied men between 21 and 45 years of age.

The operational army consisted of 11 and 1/2 infantry (six of 1st and five of the 2nd ban) and 1 cavalry division. Aged men of the 3rd ban were organized in 15 infantry regiments with some 45–50,000 men designated for use in rear and line of communications duties. However, some of them were by necessity used as part of operational army as well, bringing its strength up to around 250,000 men.[32] Serbia was in a much more disadvantageous position when compared with Austria-Hungary with regard to human reserves and replacement troops, as its only source of replacements were new recruits reaching the age of military enlistment. Their maximum annual number was theoretically around 60,000, which was insufficient to replace the losses of more than 132,000 sustained during operations from August to December 1914. This shortage of manpower forced the Serbian army to recruit under- and over-aged men to make up for losses in the opening phase of the war.

Because of the poor financial state of the Serbian economy and losses in the recent Balkan Wars, the Serbian army lacked much of the modern weaponry and equipment necessary to engage in combat with their larger and wealthier adversaries. There were only 180,000 modern rifles available for the operational army, which meant that the Serbian Army lacked between one-quarter to one-third of the rifles necessary to fully equip even their front line units, let alone reserve forces.[33] Although Serbia tried to remedy this deficit by ordering 120,000 rifles from Russia in 1914, the weapons did not begin to arrive until the second half of August. Only 1st ban troops had complete grey-green M1908 uniforms, while 2nd ban troops often wore the obsolete dark blue M1896 issue, with the 3rd ban having no proper uniforms at all and were reduced to wearing their civilian clothes with military greatcoats and caps.[34] The Serbian troops did not have service issued boots at all, and the vast majority of them wore everyday footwear made of pig skin called opanak.

Ammunition reserves were also insufficient for sustained field operations as most of it had been used in the 1912–13 Balkan wars. Artillery ammunition was sparse and only amounted to several hundred shells per unit. Because Serbia lacked a significant domestic military-industrial complex, its army was completely dependent on imports of ammunition and arms from France and Russia, which themselves were chronically short of supplies. The inevitable shortages of ammunition, which later would include a complete lack of artillery ammunition, reached their peak during decisive moments of the Austro-Hungarian invasion.

Comparative strength

These figures detail the number of all Austro-Hungarian troops concentrated on the southern (Serbian) theater of war at the beginning of August 1914 and the resources of the entire Serbian army (the number of troops actually available for the operations on both sides was however somewhat less):

| Type | Austro-Hungarian[26] | Serbian |

|---|---|---|

| Battalions | 329 | 209 |

| Batteries | 200 | 122 |

| Squadrons | 51 | 44 |

| Engineer Companies | 50 | 30 |

| Field Guns | 1243 | 718 |

| Machine Guns | 490 | 315 |

| Total Combatants | 500,000 | 344,000 |

Serbia's ally Montenegro mustered an army of some 45–50,000 men, with only 14 modern quick firing field guns, 62 machine guns and some 51 older pieces (some of them antique models from the 1870s). Unlike the Austro-Hungarian and the Serbian armies, the Montenegrin army was a militia type without proper military training or a career officer's corps.

note:

According to AH military formation,[35] the average war strength of the following units was:

Battalion:1000 (combatants)

Battery: 196

Squadron: 180

Engineer Companies: 260

Strength of corresponding Serbian units was similar:

Battalion: 1116 (combatants and non-combatants)

Battery: 169

Squadron: 130

Engineer Company: 250

Heavy artillery

| Austro-Hungarian | Serbian |

|---|---|

|

12 mobile batteries: 4 305 mm mortars 5 240 mm mortars 20 150 mm howitzers 20 120 mm cannons Additionally A-H fortresses and garrisons near the Serbian and Montenegrin borders (Petrovaradin, Sarajevo, Kotor etc.) had about 40 companies of heavy fortress artillery of various models. |

13 mobile batteries: 8 150 mm mortars Schneider-Canet M97 22 120 mm howitzers Schneider-Canet M97 |

Order of battle

Serbian army

- First Army, commanded by general Petar Bojović; Chief of Staff colonel Božidar Terzić.

- Cavalry division, four regiments, colonel Branko Jovanović

- Timok I division, four regiments, general Vladimir Kondić

- Timok II division, three regiments

- Morava II division, three regiments

- Danube II division (Braničevo detachment), six regiments

- Army artillery, colonel Božidar Srećković

- Second Army, commanded by general Stepa Stepanović; Chief of Staff colonel Vojislav Živanović

- Morava I division, colonel Ilija Gojković, four regiments

- Combined I division, general Mihajlo Rašić, four regiments, regiment commanders Svetislav Mišković, X, X and Dragoljub Uzunmirković

- Šumadija I division, four regiments

- Danube I division, colonel Milivoje Anđelković, four regiments

- Army artillery, colonel Vojislav Milojević

- Third Army, commanded by general Pavle Jurišić Šturm; Chief of Staff colonel Dušan Pešić

- Drina I division, four regiments

- Drina II division, four regiments, regiment commanders Miloje Jelisijević, X, X and X

- Obrenovac detachment, one regiment, two battalions

- Jadar Chetnik detachment

- Army artillery, colonel Miloš Mihailović

- Užice Army, commanded by general Miloš Božanović

- Šumadija II division, colonel Dragutin Milutinović, four regiments

- Užice brigade, colonel Ivan Pavlović, two regiments

- Chetnik detachments, Lim, Zlatibor, Gornjak detachments

- Army artillery

Austro-Hungarian army

August 1914:

- Balkan force

- 5th Army, commanded by Liborius Ritter von Frank

- 9. infantry division

- 21. landwehr infantry division

- 36. infantry division

- 42. Honved (Hungarian homeguard) infantry division

- 13. infantry brigade

- 11. mountain brigade

- 104. landsturm infantry brigade

- 13. march brigade

- 6th Army, commanded by Oskar Potiorek

- 1. infantry division

- 48. infantry division

- 18. infantry division

- 47. infantry division

- 40. honved infantry division

- 109. landsturm infantry brigade

- Banat Rayon and garrisons

- 107. landsturm infantry brigade

- sundry units of infantry, cavalry and artillery

- 5th Army, commanded by Liborius Ritter von Frank

- Parts of the 2nd Army, commanded by Eduard von Böhm-Ermolli

- 17. infantry division

- 34. infantry division

- 31. infantry division

- 32. infantry division

- 29. infantry division

- 7. infantry division

- 23.infantry division

- 10. cavalry division

- 4. march brigade

- 7. march brigade

- 8. march brigade

1914

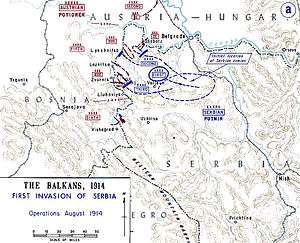

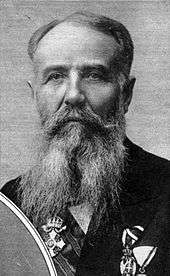

The Serbian campaign started on 28 July 1914, when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and her artillery shelled Belgrade the following day.[36] On August 12 the Austro-Hungarian armies crossed the border, the Drina River (see map).

Initially, three out of six Austro-Hungarian armies were mobilized at the Serbian frontier, but due to Russian intervention, the 2nd Army was redirected east to the Galician theater. However, since the railroad lines leading to Galicia were busy with transport of other troops, the 2nd Army could only start its departure northward on 18 August. In order to make use of the temporary presence of the 2nd Army, AOK allowed parts of it to be used in the Serbian campaign until that date. Eventually, AOK directed significant parts of the 2nd Army (around four divisions) to assist General Potiorek's main force and postponed their transportation to Russia until the last week of August. Defeats suffered in the first invasion of Serbia eventually forced AOK to transfer two divisions from 2nd Army to Potiorek's army permanently.

The V and VI Austro-Hungarian Armies had about 270,000 men who were much better equipped than the Serbs. Overall, Austro-Hungarian command was in the hands of General Potiorek. The Austro-Hungarian Empire had the third largest population in Europe in 1914, behind Russia and Germany (almost twelve times the population of the Kingdom of Serbia), giving it an enormous manpower advantage.

Battle of Cer

Potiorek rushed the attack against Serbia from northern Bosnia with his Fifth Army, supported by elements of the Second Army from Syrmia. The Second Army was due to be transported to Galicia to face the Russians at the end of August, but he made use of it until then. The Sixth was positioning itself in southern Bosnia and was not yet able to commence offensive operations. Potiorek's desire was to win a victory before Emperor Franz Joseph's birthday and to knock Serbia out as soon as possible. Thus he made two grave strategic errors by attacking with only just over half of his strength and attacking hilly western Serbia instead of the open plains of the north. This move surprised Marshal Putnik, who expected attack from the north and initially believed that it was a feint. Once it became clear that it was the main thrust, the strong Second Army under the command of General Stepa Stepanović was sent to join the small Third Army under Pavle Jurišić Šturm already facing the Austro-Hungarians and expel the invaders. After a fierce four-day battle, the Austro-Hungarians were forced to retreat, marking the first Allied victory of the war over the Central Powers led by Germany and Austria-Hungary. Casualties numbered 23,000 for the Austro-Hungarians (of whom 4,500 were captured) and 16,500 for the Serbs.

Battle of Drina

Under pressure from its allies, Serbia conducted a limited offensive across the Sava river into the Austro-Hungarian region of Syrmia with its Serbian First Army. The main operational goal was to delay the transport of the Austro-Hungarian Second Army to the Russian front. The objective was shown to be futile as forces of the Second Army were already in transport. Meanwhile, the Timok division I of the Serbian Second Army suffered a heavy defeat in a diversionary crossing, suffering around 6,000 casualties while inflicting only 2,000.

With most of his forces in Bosnia, Potiorek decided that the best way to stop the Serbian offensive was to launch another invasion into Serbia to force the Serbs to recall their troops to defend their much smaller homeland.

Winston Churchill, The Great War.[37]

7 September brought a renewed Austro-Hungarian attack from the west, across the river Drina, this time with both the Fifth Army in Mačva and the Sixth further south.[38] The initial attack by the Fifth Army was repelled by the Serbian Second Army, with 4,000 Austro-Hungarian casualties, but the stronger Sixth Army managed to surprise the Serbian Third Army and gain a foothold. After some units from the Serbian Second Army were sent to bolster the Third, the Austro-Hungarian Fifth Army also managed to establish a bridgehead with a renewed attack. At that time, Marshal Putnik withdrew the First Army from Syrmia (against much popular opposition) and used it to deliver a fierce counterattack against the Sixth Army that initially went well, but finally bogged down in a bloody four-day fight for a peak of the Jagodnja mountain called Mačkov Kamen, in which both sides suffered horrendous losses in successive frontal attacks and counterattacks. Two Serbian divisions lost around 11,000 men, while Austro-Hungarian losses were probably comparable.

Marshal Putnik ordered a retreat into the surrounding hills and the front settled into a month and a half of trench warfare, which was highly unfavourable to the Serbs, who had little in the way of an industrial base and were deficient in heavy artillery, ammunition stocks, shell production and footwear, since the vast majority of infantry wore the traditional (though state-issued) opanaks,[30] while the Austro-Hungarians had waterproof leather boots. Most of their war material was supplied by the Allies, who were short of such materials themselves. In such a situation, Serbian artillery quickly became almost silent, while the Austro-Hungarians steadily increased their fire. Serbian casualties reached 100 soldiers a day from all causes in some divisions.

During the first weeks of trench warfare, the Serbian Užice Army (first strengthened division) and the Montenegrin Sanjak Army (roughly a division) conducted an abortive offensive into Bosnia. In addition, both sides conducted a few local attacks, most of which were soundly defeated. In one such attack, the Serbian Army used mine warfare for the first time: the Combined Division dug tunnels beneath the Austro-Hungarian trenches (that were only 20–30 meters away from the Serbian ones on this sector), planted mines and set them off just before an infantry charge.

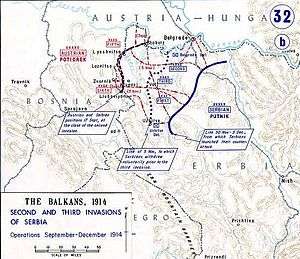

Battle of Kolubara

Having thus weakened the Serbian army, the Austro-Hungarian Army launched another massive attack on 5 November. The Serbs withdrew step by step, offering strong resistance at the Kolubara River, but to no avail, due to the lack of artillery ammunition. It was at that time that General Živojin Mišić was made commander of the battered First Army, replacing the wounded Petar Bojović. He insisted on a deep withdrawal in order to give the troops some much-needed rest and to shorten the front. Marshal Putnik finally relented, but the consequence was the abandonment of the capital city of Belgrade. After suffering heavy losses, the Austro-Hungarian Army entered the city on 2 December. This action led Potiorek to move the whole Fifth Army into the Belgrade area and use it to crush the Serbian right flank. This, however, left the Sixth alone for a few days to face the whole Serbian army.

At this point, artillery ammunition finally arrived from France and Greece. In addition, some replacements were sent to the units and Marshal Putnik correctly sensed that the Austro-Hungarian forces were dangerously overstretched and weakened in the previous offensives, so he ordered a full-scale counterattack with the entire Serbian Army on 3 December against the Sixth Army. The Fifth hurried its flanking maneuver, but it was already too late – with the Sixth Army broken, the Second and Third Serbian Armies overwhelmed the Fifth. Finally, Potiorek lost his nerve and ordered yet another retreat back across the rivers into Austria-Hungary's territory. The Serbian Army recaptured Belgrade on 15 December.

The first phase of the war against Serbia had ended with no change in the border, but casualties were enormous compared to earlier wars, albeit comparable to other campaigns of World War I. The Serbian army suffered 170,000 men killed, wounded, captured or missing. Austro-Hungarian losses were approaching 215,000 men killed, wounded or missing.. Austro-Hungarian General Potiorek was removed from command and replaced by Archduke Eugen of Austria (C. Falls p. 54). On the Serbian side, a deadly typhus epidemic killed hundreds of thousands of Serb civilians during the winter.

After the Battle of Kolubara, the Serbian Parliament adopted the Niš Declaration (7 December 1914) on the war goals of Serbia: "Convinced that the entire Serbian nation is determined to persevere in the holy struggle for the defense of their homesteads and their freedom, the government of the Kingdom (of Serbia) considers that, in these fateful times, its main and only task is to ensure the successful completion of this great warfare which, at the moment when it started, also became a struggle for the liberation and unification of all our unliberated Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian brothers. The great success which is to crown this warfare will make up for the extremely bloody sacrifices which this generation of Serbs is making". This amounted to announcing Serbia's intention to annex extensive amounts of Austria-Hungary's Balkan provinces.

1915

Prelude

Early in 1915, with Ottoman defeats at the Battle of Sarikamish and in the First Suez Offensive, the German Chief of the General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn tried to convince the Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf, of the importance of conquering Serbia. If Serbia were taken, then the Germans would have a direct rail link from Germany through Austria-Hungary, then down to Istanbul and beyond. This would allow the Germans to send military supplies and even troops to help the Ottoman Empire. While this was hardly in Austria-Hungary's interests, the Austro-Hungarians did want to defeat Serbia. However, Russia was the more dangerous enemy, and furthermore, with the entry of Italy into the war on the Allied side, the Austro-Hungarians had their hands full (see Italian Front (World War I)).

Both the Allies and the Central Powers tried to get Bulgaria to pick a side in the Great War. Bulgaria and Serbia had fought two wars in the last 30 years: the Serbo-Bulgarian War in 1885, and the Second Balkan War in 1913. The result was that the Bulgarian government and people felt that Serbia was in possession of lands to which Bulgaria was entitled, and when the Central Powers offered to give them what they claimed, the Bulgarians entered the war on their side. With the Allied loss in the Gallipoli campaign and the Russian defeat at Gorlice, King Ferdinand of Bulgaria signed a treaty with Germany and on 23 September 1915, Bulgaria began mobilizing for war.

Opposing forces

During the preceding nine months, the Serbs had tried and failed to rebuild their battered armies and improve their supply situation. Despite their efforts, the Serbian Army was only about 30,000 men stronger than at the start of the war (around 225,000) and was still badly equipped. Although Britain and France had talked about sending serious military forces to Serbia, nothing was done until it was too late. When Bulgaria began mobilizing, the French and British sent two divisions, but they arrived late in the Greek town of Salonika. Part of the reason for the delay was the National schism in Greek politics of the time that generating conflicting views about the war.

Against Serbia were marshalled the Bulgarian First Army commanded by Kliment Boyadzhiev, the German Eleventh Army commanded by Max von Gallwitz and the Austro-Hungarian Third Army commanded by Hermann Kövess von Kövessháza, all under the control of Field Marshal August von Mackensen. In addition the Bulgarian Second Army commanded by (Georgi Todorov), which remained under the direct control of the Bulgarian high command, was deployed against Macedonia.

Course of the campaign

The Austro-Hungarians and Germans began their attack on 7 October with their troops crossing the Drina and Sava rivers, covered by heavy artillery fire. Once they crossed the Danube, the Germans and Austro-Hungarians moved on Belgrade itself. Vicious street fighting ensued,[39] and the Serbs' resistance in the city was finally crushed on 9 October.[40]

Then, on 14 October, the Bulgarian Army attacked from the north of Bulgaria towards Niš and from the south towards Skopje (see map). The Bulgarian First Army defeated the Serbian Second Army at the Battle of Morava, while the Bulgarian Second Army defeated the Serbians at the Battle of Ovche Pole. With the Bulgarian breakthrough, the Serbian position became untenable; the main army in the north (around Belgrade) could either retreat or be surrounded and forced to surrender. In the Battle of Kosovo, the Serbs made a last and desperate attempt to join the two incomplete Allied divisions that made a limited advance from the south, but were unable to gather enough forces due to the pressure from the north and east. They were halted by the Bulgarians under General Todorov and had to pull back.

Marshal Putnik ordered the Great Retreat, a full retreat south and west through Montenegro and into Albania. The weather was terrible, the roads poor, and the army had to help the tens of thousands of civilians who retreated with them with almost no supplies or food left. But the bad weather and poor roads worked for the refugees as well, as the Central Powers forces could not press them hard enough, so they evaded capture. Many of the fleeing soldiers and civilians did not make it to the coast, though – they were lost to hunger, disease, and attacks by enemy forces and Albanian tribal bands,[41] due to the memory of suppressed rebellions and Massacres of Albanians in the Balkan Wars.[42][43][44]

The circumstances of the retreat were disastrous. All told, only some 155,000 Serbs, mostly soldiers, reached the coast of the Adriatic Sea and embarked on Allied transport ships that carried the army to various Greek islands (many to Corfu) before being sent to Salonika. The evacuation of the Serbian army from Albania was completed on 10 February 1916. The survivors were so weakened that thousands of them died from sheer exhaustion in the weeks after their rescue. Marshal Putnik had to be carried during the whole retreat and he died around fifteen months later in a hospital in France.

The French and British divisions had marched north from Thessaloniki in October 1915 under the command of French General Maurice Sarrail. The War Office in London was reluctant to advance too deep into Serbia, so the French divisions advanced on their own up the Vardar River. This advance gave some limited help to the retreating Serbian Army, as the Bulgarians had to concentrate larger forces on their southern flank to deal with the threat, which led to the Battle of Krivolak (October–November 1915). By the end of November, General Sarrail had to retreat in the face of massive Bulgarian assaults on his positions. During his retreat, the British at the Battle of Kosturino were also forced to retreat. By 12 December, all allied forces were back in Greece.

The Army of Serbia's ally Montenegro did not follow the Serbs into exile, but retreated to defend their own country. The Austrian-Hungarians launched their Montenegrin campaign on 5 January 1916 and despite some success of The Montenegrins in the Battle of Mojkovac, they were completely defeated within 2 weeks.

This was a nearly complete victory for the Central Powers at a cost of around 67,000 casualties as compared to around 94,000 Serbs killed or wounded and 174,000 captured, of which 70,000 were wounded.[6] The railroad from Berlin to Istanbul was finally opened. The only flaw in the victory was that much of the Serbian Army had successfully retreated, although it was left very disorganized and required rebuilding.

Aftermath

1916–1918

The Serbian army was evacuated to Greece and joined up with the Allied Army of the Orient. They then fought a trench war against the Bulgarians on the Macedonia Front. The Macedonian front in the beginning was mostly static. French and Serbian forces re-took limited areas of Macedonia by recapturing Bitola on 19 November 1916 as a result of the costly Monastir Offensive, which brought stabilization of the front.

French and Serbian troops finally made a breakthrough in the Vardar Offensive in 1918, after most of the German and Austro-Hungarian troops had withdrawn. This breakthrough was significant in defeating Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary, which led to the final victory of World War I. After the Allied breakthrough, Bulgaria capitulated on 29 September 1918.[45] Hindenburg and Ludendorff concluded that the strategic and operational balance had now shifted decidedly against the Central Powers and insisted on an immediate peace settlement during a meeting with government officials a day after the Bulgarian collapse.[46] On 29 September 1918, the German Supreme Army Command informed Kaiser Wilhelm II and the Imperial Chancellor Count Georg von Hertling, that the military situation facing Germany was hopeless .[47]

German Emperor Wilhelm II in his telegram to Bulgarian Tsar Ferdinand I stated: “Disgraceful! 62,000 Serbs decided the war!".[48][49]

The collapse of the Macedonian front meant that the road to Budapest and Vienna was now opened for the 670,000-strong army of General Franchet d'Esperey as the Bulgarian surrender deprived the Central Powers of the 278 infantry battalions and 1,500 guns (the equivalent of some 25 to 30 German divisions) that were previously holding the line.[50] The German high command responded by sending only seven infantry and one cavalry division, but these forces were far from enough for a front to be re-established.[50]

Serbs, with its well-earned reputation, spearhead the attack of the Allied armies, mostly French but aided by British and Greek troops. They pushed forward in September 1918, forced Bulgaria to leave the war and eventually managed to liberate Serbia two weeks before the end of World War I.

End of the War

The ramifications of the war were manifold. When World War I ended, the Treaty of Neuilly awarded Western Thrace to Greece, whereas Serbia received some minor territorial concessions from Bulgaria. Austria-Hungary was broken apart, and Hungary lost much land to both Yugoslavia and Romania in the Treaty of Trianon. Serbia assumed the leading position in the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia, joined by its old ally, Montenegro. Meanwhile, Italy established a quasi-protectorate over Albania and Greece re-occupied Albania's southern part, which was autonomous under a local Greek provisional government (see Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus), despite Albania's neutrality during the war.

Casualties

Before the war, the Kingdom of Serbia had 4,500,000 inhabitants.[51] According to The New York Times, 150,000 people are estimated to have died in 1915 alone during the worst typhus epidemic in world history. With the aid of the American Red Cross and 44 foreign governments, the outbreak was brought under control by the end of the year.[52] The number of civilian deaths is estimated by some sources at 650,000, primarily due to the typhus outbreak and famine, but also direct clashes with the occupiers.[53] Serbia's casualties accounted for 8% of the total Allied military deaths. 58% of the regular Serbian Army (420,000 strong) perished during the conflict.[54] According to the Serb sources, the total number of casualties is placed around 1,000,000:[55] 25% of Serbia's prewar size, and an absolute majority (57%) of its overall male population.[56] L.A. Times and N.Y. Times also cited early Serbian sources which claimed over 1,000,000 victims in their respective articles.[57][58] Modern western and non-Serb historians put the casualties number either at 45,000 military deaths and 650,000 civilian deaths[20] or 127,355 military deaths and 82,000 civilian deaths.[21]

The extent of the Serbian demographic disaster can be illustrated by the statement of the Bulgarian Prime Minister Vasil Radoslavov: "Serbia ceased to exist" (New York Times, summer 1917).[60] In July 1918 the US Secretary of State Robert Lansing urged the Americans of all religions to pray for Serbia in their respective churches.[61][62]

The Serbian Army suffered a staggering number of casualties. It was largely destroyed near the end of the war, falling from about 420,000[4] at its peak to about 100,000 at the moment of liberation.

The Serb sources claim that the Kingdom of Serbia lost 1,100,000 inhabitants during the war. Of 4.5 million people, there were 275,000 military deaths and 450,000 among the ordinary citizenry. The civilian deaths were attributable mainly to food shortages and the effects of epidemics such as Spanish flu. In addition to the military deaths, there were 133,148 wounded. According to the Yugoslav government in 1924, Serbia lost 365,164 soldiers, or 26% of all mobilized personnel, while France suffered 16.8%, Germany 15.4%, Russia 11.5%, and Italy 10.3%.

At the end of the war, there were 114,000 disabled soldiers and 500,000 orphaned children.[63]

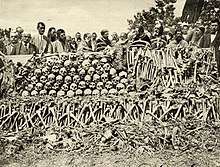

Attacks against ethnic Serb civilians

The assassination in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, was followed by violent anti-Serb demonstrations of angry Croats and Muslims[64] in the city during the evening of 28 June 1914 and for much of the following day. This happened because most Croats and many Muslims considered the archduke the best hope for the establishment of a South Slav political entity within the Habsburg Empire. The crowd directed its anger principally at shops owned by ethnic Serbs and the residences of prominent Serbs. Two ethnic Serbs were killed on 28 June by crowd violence.[65] That night there were anti-Serb demonstrations in other parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[66][67]

Incited by anti-Serbian propaganda with the collusion of the command of the Austro-Hungarian Army, soldiers committed numerous atrocities against the Serbs in both Serbia and Austria-Hungary. According to the Swiss criminologist and observer R.A. Reiss, it was a "system of extermination". In addition to executions of prisoners of war, civilian populations were subjected to mass murder and rape. Villages and towns were burned and looted. Fruit trees were cut down and water wells were poisoned in an effort on the Austro-Hungarian part to discourage Serb inhabitants from ever returning.[68][69][70]

- Austro-Hungarian propaganda postcard saying "Serbs, we'll smash you to pieces!"

Austro-Hungarian soldiers executing Serbian civilians during World War I (1916).[71]

Austro-Hungarian soldiers executing Serbian civilians during World War I (1916).[71]- Austro-Hungarian firing squad executing Serbian civilians in 1917

See also

- Albania during World War I

- Momčilo Gavrić (soldier)

- Serbian army's retreat through Albania (World War I)

- World War I casualties

References

- Number is for total Montenegrin losses in the war, including the Macedonian front.

- Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg — Wien: Verlag der Militärwissenschaftlichen Mitteilungen, 1930. — Vol. 1. pg. 759. This is the total number of soldiers who served on the Balkans until the middle of December 1914.

- Prit Buttar 2015, p. 594.

- Josephus Nelson Larned 1924, p. 9991.

- http://www.vojska.net/eng/world-war-1/serbia/organization/1914/

- Thomas & Babac. "Armies in the Balkans 1914–1918" pg.12

- DiNardo 2015, p. 122.

- Lyon 2015, p. 234.

- Георги Бакалов, "История на Българите: Военна история на българите от древността до наши дни", p.463

- Spencer Tucker, "Encyclopedia of World War I"(2005) pg 1077, ISBN 1851094202

- Lyon 2015, p. 235.

- International Labour Office, Enquête sur la production. Rapport général. Paris [etc.] Berger-Levrault, 1923–25. Tom 4 , II Les tués et les disparus p.29

- Military Casualties-World War-Estimated," Statistics Branch, GS, War Department, 25 February 1924; cited in World War I: People, Politics, and Power, published by Britannica Educational Publishing (2010) Page 219

- Urlanis, Boris (1971). Wars and Population. Moscow Pages 66,79,83, 85,160,171 and 268.

- Hughes Philpott 2005, p.48

- Hart 2013, p.325>

- DiNardo 2015, p. 117

- Fred Singleton (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 9780521274852.

ww1 Serbian army entered belgrade.

- Чедомир Антић, Судњи рат, Политика од 14. септембра 2008.

- Владимир Радомировић, Највећа српска победа, Политика од 14. септембра 2008.

- Sammis 2002, p. 32.

- Tucker 2005, p. 273.

- Keegan 1998, pp. 48–49

- Willmott 2003, pp. 2–23

- Willmott 2003, p. 26

- Willmott 2003, p. 27

- Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg 1914 - 1918, vol. 1, Wienn 1930, p68

- http://digi.landesbibliothek.at/viewer/image/AC03568741/1/LOG_0003/ Die Entwicklung der öst.-ung. Wehrmacht in den ersten zwei Kriegsjahren, 10

- http://digi.landesbibliothek.at/viewer/image/AC01351505/1/LOG_0003/ Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg 1914 -1918, vol. 2 Beilagen, Wienn 1930, table I )

- http://honsi.org/literature/svejk/dokumenty/oulk/band1.html Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg 1914 - 1918, vol. 1, Wienn 1930, p68

- Jordan 2008, p. 20

- Willmott 2009, p. 69

- James Lyon, A peasant mob: The Serbian army in the eve of the Great War, JMH 61, 1997, p501

- James Lyon, p496

- Thomas, Nigel (2001). Armies in the Balkans 1914-18. p. 38. ISBN 1-84176-194-X.

- Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg 1914 - 1918, vol. 1, Wienn 1930, p.82

- Gordon Martel, The Origins of the First World War, Pearson Longman, Harlow, 2003, p. xii f.

- Jordan 2008, p. 25

- Jordan 2008, p. 31

- Jordan 2008, p. 53

- Willmott 2008, p. 120

- Tucker & Roberts 2005, pp. 1075–6

- DiNardo, Richard L. (2015). Invasion: The Conquest of Serbia, 1915: The Conquest of Serbia, 1915 ("The Muslim population of Serbia had been subjekt to all manner of mistreatment oat the hands of the Serbian Orthodox majority during the Balkan Wars." ed.). ABC-CLIO. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-1-4408-0093-1. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Lieberman, Benjamin (2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe ("Driven out of the north and east, the Serb retreat ended up in Kosovo in November 1915. This new addition to Serbia, the scene of nationalist triumph only three yars earlier, was not hospitable ground for the fleeing Serbs. A large majority of the population was made up of Albanians. These Albanians lived with the memory of suppressed rebellions and recent massacres carried out by Serbs during the Blakan wars. " ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-1-4422-3038-5. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Eric, Sass. "Serbian "Great Retreat" Begins". Mentalfloss. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Tucker, Wood & Murphy 1999, p. 120

- Robert A. DOUGHTY (2005). Pyrrhic Victory. Harvard University Press. pp. 491–. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Axelrod 2018, p. 260.

- Editor. "The Battle of Dobro Polje – The Forgotten Balkan Skirmish That Ended WW1 | Militaryhistorynow.com". Retrieved 2019-11-21.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Editor. "The Germans Could no Longer Keep up the Fight | historycollection.co". Retrieved 2019-11-21.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Korsun, N. "The Balkan Front of the World War (in Russian)". militera.lib.ru. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- "Serbia in 1914".

- "$1,600,000 was raised for the Red Cross" (PDF). The New York Times. 29 October 1915.

- "First World War.com - Feature Articles - The Minor Powers During World War One - Serbia". www.firstworldwar.com.

- Serbian army, August 1914

- "Политика Online". www.politika.rs.

- Тема недеље : Највећа српска победа : Сви српски тријумфи : ПОЛИТИКА (in Serbian)

- "Fourth of Serbia's population dead". Archived from the original on 2013-07-21. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- "Asserts Serbians face extinction" (PDF).

- Mitrović 2007, p. 223.

- "Serbia restored" (PDF).

- "Serbia and Austria" (PDF). New York Times. 28 July 1918.

- "Appeals to Americans to pray for Serbians" (PDF). New York Times. 27 July 1918.

- Banac, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 222. ISBN 9780801494932.

its postwar population included some 114,000 invalids and over half a million orphans

- Christopher Bennett (1995). Yugoslavia's Bloody Collapse: Causes, Course and Consequences. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 259. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- Robert J. Donia (2006). Sarajevo: A Biography. University of Michigan Press. pp. 123–. ISBN 0-472-11557-X.

- Joseph Ward Swain (1933). Beginning the twentieth century: a history of the generation that made the war. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Christopher Bennett (January 1995). Yugoslavia's Bloody Collapse: Causes, Course and Consequences. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-85065-232-8.

- How Austria-Hungary waged war in Serbia (1915) German criminologist R.A. Reiss on atrocities by the Austro-Hungarian army

- Augenzeugen. Der Krieg gegen Zivilisten. Fotografien aus dem Ersten Weltkrieg Anton Holzer, Vienna

- "Executions, various". www.ww1-propaganda-cards.com.

- Honzík, Miroslav; Honzíková, Hana (1984). 1914/1918, Léta zkázy a naděje. Czech Republic: Panorama.

Sources

Books

- Babac, Dušan M. (2016). The Serbian Army in the Great War, 1914-1918. Solihull: Helion.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buttar, Prit (2014). Collision of Empires: The War on the Eastern Front in 1914. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cox, John K. (2002). The History of Serbia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DiNardo, Richard L. (2015). Invasion: The Conquest of Serbia, 1915. Santa Barbara: Praeger.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Đorđević, M. P.; Živojinović, D. R. (1991). Srbija i Jugosloveni za vreme rata 1914-1918. 5. Beograd: Biblioteka grada Beograda.

- Dragnich, Alex N. (2004). Serbia Through the Ages. Boulder: East European Monographs.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Falls, Cyril, The Great War (1960) 978-1440800924

- Fryer, Charles (1997). The Destruction of Serbia in 1915. New York: Columbia University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gumz, Jonathan E. (2009). The Resurrection and Collapse of Empire in Habsburg Serbia, 1914-1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hadži-Vasiljević, Jovan (1922). Bugarska zverstva u Vranju i okolini, 1915-1918. Zastava.

- Peter Hart (2013). The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-997627-0.

- M. Hughes; W. Philpott (29 March 2005). The Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of the First World War. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-230-50480-6.

- Jordan, David (2008). The Balkans, Italy & Africa 1914–1918: From Sarajevo to the Piave and Lake Tanganyika. London: Amber Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lyon, James B. (2015). Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War. London: Bloomsbury.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War 1914-1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg 1914 - 1918, vol. 1, Wienn 1930

- Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg 1914 -1918, vol. 2 Beilagen, Wienn 1931

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sammis, Kathy (2002). Focus on World History: The Twentieth Century. 5. Walch Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9780825143717.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hew Strachan (1998). World War I: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820614-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Temperley, Harold W. V. (1919) [1917]. History of Serbia (PDF) (2 ed.). London: Bell and Sons.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomac, Petar; Đurašinović, Radomir (1973). Prvi svetski rat, 1914-1918. Vojnoizdavački zavod.

- Tucker, Spencer (2005). World War I: Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 273. ISBN 9781851094202.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Willmott, H. P. (2003). World War I. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7894-9627-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Willmott, H. P. (2008). World War I. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-1-4053-2986-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Willmott, H. P. (2009). World War I. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7566-5015-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Axelrod, Alan (2018). How America Won World War I. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1493031924.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Josephus Nelson Larned (1924). The New Larned History for Ready Reference, Reading and Research: The Actual Words of the World's Best Historians, Biographers and Specialists; a Complete System of History for All Uses, Extending to All Countries and Subjects and Representing the Better and Newer Literature of History. C.A. Nichols Publishing Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prit Buttar (2015). Germany Ascendant: The Eastern Front 1915. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-1355-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Journals

- Silberstein, Gerard E. "The Serbian campaign of 1915: Its diplomatic background." American Historical Review 73.1 (1967): 51-69 online

- Pisarri, Milovan (2013). "Bulgarian Crimes Against Civilians in Occupied Serbia during the First World War". Balcanica. 44: 357–390.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Radić, Radmila (2015). "The Serbian Orthodox Church in the First World War". The Serbs and the First World War 1914-1918. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. pp. 263–285.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Radojević, Mira (2015). "Jovan M. Jovanović on the outbreak of the First World War". The Serbs and the First World War 1914-1918. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. pp. 187–204.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Serbia in World War I. |

- Bjelajac, Mile: Serbia, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Tasić, Dmitar: Warfare 1914-1918 (South East Europe), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Years which changed the war - WWI in documents from Archive of Serbia

- "Jugoslovenska kinoteka" (in Serbian). Kinoteka.

- Popović, Andra (1926). Ратни албум : 1914-1918. Збирка књига Универзитетске библиотеке у Београду (in Serbian). Digital National Library of Serbia.

- W. H. Crawfurd Price (1918). Serbia's Part in the War ... Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Company. (Public Domain)