Hungarian–Romanian War

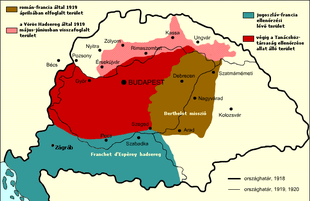

The Hungarian–Romanian War was fought between Hungary and Romania from 13 November 1918 to 3 August 1919. It started as a Romanian military campaign on the eastern parts of the self-disarmed Kingdom of Hungary on 13 November 1918, and continued against the First Hungarian Republic, and from March 1919 against the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The Romanian Army occupied eastern Hungary until 28 March 1920.

| Hungarian–Romanian War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the revolutions and interventions in Hungary | |||||||

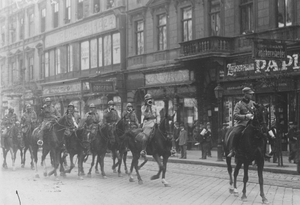

Romanian cavalry in Budapest | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000–80,000 | 10,000–96,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,000 killed[1] | ||||||

Background

Hungary after World War 1.

Aster Revolution, liberal republic and the self-disarmament of Hungary

In 1918, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy politically collapsed and disintegrated as a result of its defeat on the Italian Front (World War I). During the war, the liberal Hungarian aristocrat Count Mihály Károlyi led a small but very active pacifist anti-war maverick fraction in the Hungarian parliament.[2] He even organized covert contacts with British and French diplomats in Switzerland during the war.[3] On 31 October 1918, the Aster Revolution in Budapest brought Count Mihály Károlyi, a supporter of the Allied Powers, to power. The Hungarian Royal Honvéd army still had more than 1,400,000 soldiers[4][5] when Mihály Károlyi was announced as prime minister of Hungary. Károlyi yielded to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's demand for pacifism by ordering the disarmament of the Hungarian army. This happened under the direction of Béla Linder (minister of war) on 2 November 1918.[6][7] Due to the full disarmament of its army, Hungary was to remain without a national defence at a time of particular vulnerability. Oszkár Jászi, Minister for National Minorities of Hungary, offered democratic referendums about the disputed borders for minorities (such as the Romanians in Transylvania); however, the political leaders of those minorities refused the very idea of democratic referendums regarding disputed territories.[8] After the Hungarian self-disarmament, Czech, Serbian, and Romanian political leaders chose to attack Hungary instead of holding democratic plebiscites concerning the disputed areas.

International reactions after the Hungarian self-disarmament

Six days later, on 5 November 1918, the Serbian Army, with the help of the French Army, crossed the southern border of the Kingdom of Hungary. On 8 November, the Czechoslovak Army crossed the northern border, and on 13 November, the Romanian Army crossed the eastern border. On 13 November, Károlyi signed an armistice with the Allied nations in Belgrade. It limited the size of the Hungarian army to six infantry and two cavalry divisions.[9] Demarcation lines defining the territory to remain under Hungarian control were made.

The lines would apply until definitive borders could be established. Under the terms of the armistice, Serbian and French troops advanced from the south, taking control of the Banat and Croatia. Czechoslovakia took control of Upper Hungary and Carpathian Ruthenia. Romanian forces were permitted to advance to the River Maros (Mureș). However, on 14 November, Serbia occupied Pécs.[10][11] The Hungarian self-disarmament made the occupation of Hungary directly possible for the relatively small armies of Romania, the Franco-Serbian army and the armed forces of the newly established Czechoslovakia. During the rule of Károlyi's pacifist cabinet, Hungary lost the control over approximately 75% of its former pre-WWI territories (325,411 km2 (125,642 sq mi)) without a fight, and was subject to foreign occupation.[12]

Interventions, fall of the liberal regime and communist coup d'état

The Károlyi government failed to manage both domestic and military issues and lost popular support. On 20 March 1919, Béla Kun, who had been imprisoned in the Markó Street prison, was released.[13] On 21 March, he led a successful communist coup d'état; Károlyi was deposed and arrested.[14] Kun formed a social democratic, communist coalition government and proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Days later the Communists purged the Social Democrats from the government.[15][16] The Hungarian Soviet Republic was a small communist rump state.[17] When the Republic of Councils in Hungary was established, it controlled only approximately 23 percent of the Hungary's historic territory.

The Communists remained bitterly unpopular[18] in the Hungarian countryside, where the authority of that government was often nonexistent.[19] The communist party and communist policies only had real popular support among the proletarian masses of large industrial centers – especially in Budapest – where the working class represented a high proportion of the population. The communist government followed the Soviet model: the party established its terror groups (like the infamous Lenin Boys) to "overcome the obstacles" in the Hungarian countryside. This was later known as the Red Terror in Hungary.

The new government promised equality and social justice. It proposed that Hungary be restructured as a federation. The proposal was designed to appeal to both domestic and foreign opinion. Domestic considerations included maintaining the territorial integrity and economic unity of former crown lands, and protecting the nation's borders. The government had popular support and the support of the army. Most of the officers in the Hungarian army came from regions that had been forcibly occupied during World War I. This heightened their patriotic mood.[20] Hungary as a federation would appeal to President Wilson under his doctrine of self-determination of peoples due to the nation's multi-ethnic composition. In addition, self-governed and self-directed institutions for the non-Magyar peoples of Hungary would lessen the dominance of the Magyar people.[20]

Romania during and after World War 1.

In 1916, Romania entered World War I on the side of the Allies. In doing so, Romania's goal was to unite all the territories with a Romanian national majority into one state. In the Treaty of Bucharest (1916), terms for Romania's acquisition of territories within Austria-Hungary were stipulated.

After three months of war, two-thirds of the territory of the Kingdom of Romania was occupied by the Central Powers. The capital city of Romania, Bucharest was captured by the Central Powers on 6 December 1916. German general August von Mackensen was appointed as the "military governor" of the occupied territories of Romania.[21]

In 1918, after the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks signed a separate peace with the Central Powers in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Romania was alone on the Eastern Front, a situation that far surpassed its military capabilities. Therefore, on 7 May 1918, Romania sued for peace. The prime minister of Romania, Alexandru Marghiloman, signed the Treaty of Bucharest (1918) with the Central Powers. However, this treaty was never signed by King Ferdinand of Romania.

At the end of 1918, Romania's situation was dire. She was suffering from the consequences of punitive war reparations.[22] Dobruja was under Bulgarian occupation. The German army under the command of Field Marshal August von Mackensen was retreating through Romania. The bulk of the Romanian army was demobilized, leaving only four full-strength divisions. A further eight divisions were left in a reserve status. The four battle-ready divisions were used to keep order and protect Bessarabia from possible hostile actions of Soviet Russia. On 10 November 1918 Romania re-entered the war on the side of the Allied forces, with similar objectives to those of 1916. King Ferdinand called for the mobilization of the Romanian Army and ordered it to attack by crossing the Carpathian Mountains into Transylvania. The end of World War I that soon followed did not bring an end to fighting for the Romanian Army. Its action continued into 1918 and 1919 in the Hungarian–Romanian war.

November 1918 – March 1919

Following the 1918 Treaty of Bucharest, the bulk of the Romanian Army was demobilized. Only the 9th and 10th infantry divisions and the 1st and 2nd cavalry divisions were at full strength. However, those units were engaged in the protection of Bessarabia against the Bolshevik Soviet Russians. The 1st, 7th and 8th Vânători de munte divisions, stationed in Moldavia, were the first units to be mobilized. The 8th was sent to Bukovina and the other two were sent to Transylvania. On 13 November, the 7th entered Transylvania at the Prisăcani River in the eastern Carpathians. The 1st then entered Transylvania at Palanca, Bacău.[23]

On 1 December, the Union of Transylvania with Romania was officiated by the elected representatives of the Romanian people of Transylvania, who proclaimed a union with Romania. Later the Transylvanian Saxons and Banat Swabians also supported the union.[24][25] On 7 December, Brașov was occupied by the Romanian Army.[26] Later that month, Romanian units reached the line of the Maros (Mureș) River. This was a demarcation line agreed upon by the representatives of the Allied powers and Hungary at the Armistice of Belgrade. At the same time units of the German army, under the command of Marshal August von Mackensen, retreated to the west.

Following a request from Romania, the Allied Command in the east under the leadership of French Genenral Louis Franchet d'Espèrey allowed the Romanian army to advance to the line of the western Carpathians. The 7th Vânători division advanced in the direction of Kolozsvár (Cluj), while the 1st division advanced in the direction of Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia). On 24 December, units of the Romanian Army entered Cluj.[26] By 22 January 1919, the Romanian army controlled all the territory to the Maros River. The 7th and 1st divisions were spread thin, so the 2nd Division was sent to Nagyszeben (Sibiu) and the 6th Division to Brassó (Brașov). Two new infantry divisions, the 16th and 18th, were formed from Romanian soldiers previously mobilized in the Austro-Hungarian Army. A unified command of the Romanian Army in Transylvania was established. Its headquarters were at Sibiu, with Gen. Traian Moşoiu in command. Although Romania controlled new territories, it did not encompass all the ethnic Romanian population in the region.

On 28 February 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference, the council of the Allied nations notified Hungary of a new demarcation line to which the Romanian army would advance. This line coincided with railways connecting Szatmárnémeti (Satu Mare), Nagyvárad (Oradea), and Arad. However, the Romanian army was not to enter these cities. A demilitarized zone was to be created, extending from the new demarcation line to 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) beyond the line. The demilitarized zone represented the extent of Romanian territorial requests on Hungary. The retreat of the Hungarian army behind the western border of the demilitarized zone was to begin on 22 March.

On 19 March, Hungary received notification of the new demarcation line and demilitarized zone from French Lieutenant Colonel Fernand Vix (the "Vix note"). The Károlyi government would not accept the terms and this was a trigger for the coup d'état by Béla Kun, who formed the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Around this time, limited skirmishes took place between Romanian and Hungarian troops. Some Hungarian elements engaged in the harassment of the Romanian population outside the area controlled by the Romanian Army.[27]

April–June 1919

After 21 March 1919, Romania found itself between two nations with communist governments: Hungary to the west and the Russian SFSR to the east. The Romanian delegation at the Paris Peace Conference asked that the Romanian Army be allowed to oust Kun's communist government in Hungary. The Allied council was aware of the communist danger to Romania. However, there was a climate of dissension in the council among U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau about guarantees required by France on its borders with Germany. In particular, the American delegation was convinced that French hardliners around Marshal Ferdinand Foch were trying to initiate a new conflict with Germany and Soviet Russia. The Allied council did try to defuse the situation between Romania and Hungary.

On 4 April, South African General Jan Smuts was sent to Hungary. He carried the proposition that the Hungarian communist government under Kun abide by the conditions previously presented to Károlyi in the Vix note. Smuts' mission also represented official recognition of the Kun communist government by the Allied council. He may have asked if Kun would act as a conduit for communication between the Allied council and the Bolshevik Soviet Russians.[28] In exchange for Hungary's agreement to the conditions set out in the Vix note, the Allied powers promised to lift the blockade of Hungary and a take a benevolent attitude towards Hungary's loss of territory to Romania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Kun refused the terms, demanding that Romanian forces return to the line of the Maros River. Smuts' negotiations ceased.

Kun stalled for time in order to build a force capable of fighting Romania and Czechoslovakia. Hungary had 20,000 troops facing the Romanian Army and mobilized a further 60,000. There were recruitment centers in towns such as Nagyvárad, Gyula, Debrecen, and Szolnok. There were some elite units and officers from the former Austro-Hungarian Army, but there were also volunteers with little training. The Hungarian troops were equipped with 137 cannons and five armored trains. They were motivated by nationalist sentiments rather than communist ideals. Kun hoped that Soviet Russia would attack Romania from the east.

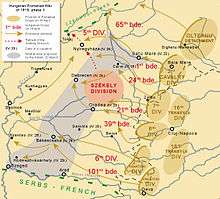

When Kun declined the terms of the Vix note, Romania acted to enforce the new railway demarcation line.[27]:p. 550. The Romanian army in Transylvania included 64 infantry battalions, 28 cavalry squadrons, 160 cannons, 32 howitzers, one armored train, two air squadrons and two pioneer battalions, one north and one south. General Gheorghe Mărdărescu commanded the Romanian army in Transylvania. The commander of the north battalion was General Moşoiu. Romania planned to take offensive action on 16 April 1919. The north battalion was to take Nagykároly (today Carei) and Nagyvárad (today Oradea. This would separate the elite Hungarian Székely division from the rest of the Hungarian army. The north battalion would then outflank the Hungarian Army. Simultaneously, the south battalion would advance to Máriaradna (today part of Lipova) and Belényes (today Beiuș)).

Hostilities begin

Foreign policy scandal: the establishment of the Slovak Soviet Republic

In late May, after the Entente military representative demanded more territorial concessions from Hungary, Kun attempted to "fulfill" his promise to adhere to Hungary's historical borders. The men of the Hungarian Red Army were recruited mainly from the volunteers of the Budapest proletariat.[29]

In June, the Hungarian Red Army invaded the eastern part of the newly-forming Czechoslovak state, approximately the former Upper Hungary. The Hungarian Red Army achieved some military success early on: under the leadership of Colonel Aurél Stromfeld, it ousted Czechoslovak troops from the north and planned to march against the Romanian Army in the east.

Kun ordered the preparation of an offensive against Czechoslovakia, which would increase his domestic support by making good on his promise to restore Hungary's borders. The Hungarian Red Army recruited men between 19–25 years of age. Industrial workers from Budapest volunteered. Many former Austro-Hungarian officers re-enlisted for patriotic reasons. The Hungarian Red Army moved its 1st and 5th artillery divisions—40 battalions—to Upper Hungary.

On 20 May 1919, a force under Colonel Aurél Stromfeld attacked and routed Czechoslovak troops from Miskolc. The Romanian Army attacked the Hungarian flank with troops from the 16th Infantry Division and the Second Vânători Division, aiming to maintain contact with the Czechoslovak Army. Hungarian troops prevailed and the Romanian Army retreated to its bridgehead at Tokaj. There, between 25–30 May, Romanian forces were required to defend their position against Hungarian attacks.

On 3 June, the Romanian Army was forced into further retreat but extended its line of defence along the Tisza River and reinforced its position with the 8th Division, which had been moving forward from Bukovina since 22 May. Hungary at the time controlled the territory from its old borders and had regained control of industrial areas around Miskolc, Salgótarján, Selmecbánya, and Kassa.

Demoralization of the Red Army

Despite promises for the restoration of the former borders of Hungary, the communists declared the establishment of the Slovak Soviet Republic in Prešov (Eperjes) on 16 June 1919.[30] After the proclamation of the Slovak Soviet Republic, the Hungarian nationalists and patriots soon realized that the new communist government had no intentions to recapture the lost territories, only to spread communist ideology and establish other communist states in Europe, thus sacrificing Hungarian national interests.[31]

The Hungarian patriots and professional military officers in the Red Army saw the establishment of the Slovak Soviet Republic as a betrayal, and their support for the government began to erode (the communists and their government supported the establishment of the Slovak Communist state, while the Hungarian patriots wanted to keep the reoccupied territories for Hungary). Despite a series of military victories against the Czechoslovak army, the Hungarian Red Army started to disintegrate due to tension between nationalists and communists during the establishment of the Slovak Soviet Republic. The concession eroded support of the communist government among professional military officers and nationalists in the Hungarian Red Army; even the chief of the general staff Aurél Stromfeld, resigned his post in protest.[32]

When the French promised the Hungarian government that Romanian forces would withdraw from the Tiszántúl, Kun withdrew his remaining military units who had remained loyal after the political fiasco in Upper Hungary. Kun then unsuccessfully tried to turn the remaining units of the demoralized Hungarian Red Army on the Romanians.

When Kun became aware of Romanian preparations for an offensive, he fortified mountain passes in the territory controlled by the Hungarian Red Army. Then, on the night of 15–16 April, the Hungarians launched a preemptive attack. The Romanian lines held. On 16 April, the Romanian Army commenced its offensive. After heavy fighting, the Romanians took the mountain passes. On the front of the 2nd Vânători division a battalion of Hungarian cadets offered strong resistance. However, they were defeated by the 9th Regiment.

By 18 April, the first elements of the Romanian offensive were completed and the Hungarian front was broken. On 19 April, Romanian forces took Nagykároly (Carei) and on 20 April they took Nagyvárad (Oradea) and Nagyszalonta (Salonta). Rather than following the instructions of the Vix note, the Romanian Army pressed on for the Tisza River, an easily defended natural military obstacle.[33][34]

The Romanian Army reaches the Tisza river

On 23 April, Debrecen was occupied by Romanian forces.[35] The Romanian Army then began preparations for an assault on Békéscsaba. On 25–26 April, after some heavy fighting, Békéscsaba fell to Romanian forces. The Hungarians retreated to Szolnok and from there across the Tisza River. They established two concentric defense lines extending from the Tisza River around Szolnok. Between 29 April and 1 May, the Romanian Army broke through these lines. On the evening of 1 May the entire east bank of the Tisza River was under the control of the Romanian Army.

On 30 April, French Foreign Minister Stéphen Pichon summoned Ion I.C. Brătianu, the Romanian representative to the Paris Peace Conference. Romania was told to cease its advance at the Tisza River and retreat to the first demarcation line imposed by the Allied council. Brătianu promised that Romanian troops would not cross the Tisza River. On 2 May, Hungary sued for peace via a request delivered by his representative, Lieutenant Colonel Henrik Werth. Kun was prepared to recognize all of Romania's territorial demands; requested the cessation of hostilities; and asked for ongoing control of Hungarian internal affairs.

Romania offered an armistice but this was given only under pressure from the Allied council. General Moşoiu became the governor of the military district between the Romanian border and the Tisza River. General Mihăescu became commander of the north battalion. The 7th Division was moved to the Russian front in Moldavia.

Incursions by Bolshevik Soviet Russia

The Union of Bessarabia with Romania was signed on 9 April 1918. The unification act that brought these lands within the modern Romanian state was not recognized by Bolshevik Soviet Russia, but it was occupied with fighting the White movement, Poland and the Ukraine in its war for independence, and resources were not available to challenge Romania. The Bolshevik Soviet Russians might have used Ukrainian paramilitary leader Nikifor Grigoriev to challenge Romania, but circumstances for this plan did not prove favorable.

Prior to communist rule in Hungary, Soviet Russia had engaged the Odessa Soviet Republic to invade Romania. Odessa made sporadic attacks across the Dniester River in order to reclaim territory from the Bessarabia Governorate. The Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, established in 1924, was later used in this way. Romania successfully repelled these incursions. After the commencement of communist rule in Hungary, Soviet Russia pressured Romania with ultimatums and threats of war. Although a Romanian army division and some other newly formed units were moved from the Hungarian front to Bessarabia, these threats did not deter Romania's actions in Hungary.

On 9 February 1918, the Central Powers and Ukraine signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which recognised Ukraine as a neutral and independent state. Incursions into Romanian territory ceased. From January–May 1919, there were some further limited actions by Soviet forces against Romania. In late January the Ukrainian army under Bolshevik command moved towards Zbruch. Ukrainian forces took Khotyn, a town that had been occupied by Romania since 10 November 1918. Ukrainian forces held Khotyn for a few days before being routed by the Romanian Army.

At the time Soviet Russia was fending off attacks by the Armed Forces of South Russia led by Anton Denikin. Three French and two Greek army divisions under General d'Anselme, with support from Polish, Ukrainian and Russian volunteers, attacked Soviet troops near Odessa. On 21 March 1919, in support of the allied attack, Romanian troops of the 39th Regiment occupied Tiraspol.

In April, at Berzov, the Bolshevik Soviet Russian 3rd Army defeated d'Anselme's forces, which retreated towards Odessa. In late April a change in government in France led to withdrawal of the Allied forces from Odessa. The troops left by ship, abandoning some heavy equipment. Some troops, with Ukrainian and Russian volunteers, retreated through southern Bessarabia. At the same time the Romanian army fortified its positions in Bessarabia.

On 1 May, Bolshevik Soviet Russian Foreign Minister Georgy Chicherin issued an ultimatum to the Romanian government. Romania was ordered to leave Bessarabia. Under the command of Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko, Bolshevik Soviet Russian troops gathered along the Dniester River in preparation for a large attack on Bessarabia on 10 May. Bolshevik Soviet Russian attacks in Bessarabia intensified, peaking on 27–28 May with an action at Tighina. In preparation for this attack, the Bolshevik Soviet Russians threw manifestos from a plane, inviting Allied troops to fraternize with them. Sixty French soldiers crossed the Dniester River to support the Russians. The Bolshevik Soviet Russian forces entered Tighina and held the town for a number of hours.

The Romanian Army's 4th and 5th infantry divisions were moved to Bessarabia. In southern Bessarabia a territorial command unit formed by the Romanian Army's 15th Infantry Division was established. By the end of June tensions in the area had eased.

July 1919 – August 1919

The Allied council was deeply displeased by the Romanian advance to the Tisza River. Some blamed Romania for the loss of Hungary to communist rule. The Allied council asked Romania to retreat to the first railway demarcation line and commence negotiations with the Kun government. Romania persisted at the Tisza line. The Allied council pressured Hungary to stop its incursions into Czechoslovakia, threatening a coordinated action against Hungary by French, Serb and Romanian forces from the south and the east. However, the Allied council also promised favor to Hungary in subsequent peace negotiations in delineating Hungary's new borders. On 12 June, the Allied council discussed Hungary's proposed new borders with Romania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.

On 23 June, Hungary signed an armistice with Czechoslovakia. By 4 July, the Hungarian Army had retreated 15 km south of the Hungarian–Czechoslovak demarcation line. The Allied council demanded that Romania leave Tiszántúl and respect the new borders. Romania said it would only do so after the Hungarian Army demobilized. Kun said he would continue to depend on the might of his army. On 11 July, the Allied council ordered Marshal Ferdinand Foch to prepare a coordinated attack against Hungary using Serb, French and Romanian forces. Hungary, in turn, prepared for action along the Tisza River.[36]

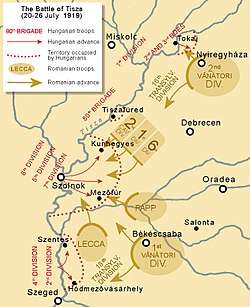

The Romanian army faced the Hungarian army along the Tisza River front line over a distance of 250 kilometres (160 mi). The front extended from beyond Szeged in the south—adjacent to French and Serb troops—to Tokaj in the north—adjacent to Czechoslovak troops. On 17 July, Hungary attacked.

Hungarian Army in July 1919

Kun's political commissars directed the Hungarian Army, supported by experienced professional military officers. Commanders of small units were experienced soldiers. The Hungarian Army mustered 100 infantry battalions (50,000 men), ten cavalry squadrons (1365 men), 69 artillery batteries of calibers up to 305 mm and nine armored trains. The troops were organized into three groups: north, central and south. The central group was the strongest.

Hungary planned to cross the Tisza River with all three groups. The north group would advance towards Szatmárnémeti, the central group to Nagyvárad and the south group to Arad. The aim was to ignite a communist uprising in Romania and incite Bolshevik Soviet Russia to attack Bessarabia.

Romanian Army in July 1919

The Romanian Army was composed of 92 battalions (48,000 men), 58 cavalry squadrons (12,000 men), 80 artillery batteries of calibers up to 155 mm, two armored trains and some support units. They were positioned along three lines. The first line was manned by the 16th Division in the north and the 18th Division in the south. More powerful units manned the second line: the 2nd Vânători Division in the north, concentrated in and around Nyíregyháza, and the 1st Vânători Division in the south, concentrated in and around Békéscsaba.

The third line was manned by Romania's strongest units: the 1st and 6th infantry divisions, the 1st and 2nd cavalry divisions and support units. The third line lay on the railway from Nagykároly, through Nagyvárad and north of Arad. The 20th and 21st infantry divisions were tasked with maintaining public order behind the third line. The first line was thin, as it was supposed to fight delaying actions until the true intentions of the attacking Hungarian army were revealed. After that, together with troops in the second line, the first line was to be held until troops in the third line could mount a counterattack. The Romanian command planned to use the railways under its control to move troops. The Romanian soldier was usually a World War I veteran.

Hungarian offensive

From 17–20 July, the Hungarian army bombarded the Romanian positions and conducted reconnaissance operations. On 20 July, at about 3 a.m., after a fierce bombardment, Hungarian infantry including all three groups crossed the Tisza River and attacked Romanian positions. On 20 July, in the northern arena, the Hungarians army Rakamaz and some nearby villages. Troops of the Romanian 16th and 2nd Vânători divisions took back the villages shortly and regained Rakamaz the next day. The Hungarians renewed their efforts and, supported by artillery fire, retook Rakamaz and two nearby villages but could not break out of the Rakamaz bridgehead.

Hungarian forces attempted to outflank the Romanian positions by crossing the Tisza River at Tiszafüred with troops of the 80th International Brigade. There they were halted by troops of the Romanian 16th Division. On 24 July, the Romanian 20th Infantry Division, brought in as reinforcements, cleared the bridgehead at Tiszafüred. Not being able to break out of Rakamaz, Hungarian forces fortified their positions and redeployed some troops. There was a lull in fighting in the north, as the Romanian troops did the same. On 26 July, the Romanians attacked, and by 10 p.m. had cleared the Rakamaz bridgehead. This left the Romanian army in control of the northern part of the Tisza's eastern bank.

In the southern area, during a two-day battle, the Hungarian 2nd Division took Szentes from the 89th and 90th regiments of the Romanian 18th Division. On 21–22 July, Hódmezővásárhely changed hands several times between Hungarian and Romanian troops of the 90th Infantry Regiment supported by the 1st Vânători Brigade. On 23 July, Romanian forces reoccupied Hódmezővásárhely, Szentes and Mindszent. The Romanians controlled the eastern bank of the Tisza River in this sector, which allowed the 1st Vânători Brigade to move to the center. On 20 July, Hungarian forces established a solid bridgehead on the east bank of the Tisza at Szolnok, opposed by the Romanian 91st Regiment of the 18th Infantry Division. The Hungarian army moved the 6th and 7th divisions across the Tisza River, formed up within the bridgehead, then attacked the Romanians in the first line of defense. The Hungarian 6th Infantry Division took Törökszentmiklós; the 7th Division advanced towards Mezőtúr and the 5th Division advanced towards Túrkeve.

On 22 July, Hungarian forces crossed the Tisza River at a point 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of Szolnok and took Kunhegyes from the Romanian 18th Vânători Regiment. The Romanian 18th Division was reinforced with units from the second line, including some troops from the 1st Cavalry Division and the entire 2nd Vânători Brigade. On 23 July, Hungarian forces took Túrkeve and Mezőtúr. The Hungarian army controlled an area 80 kilometres (50 mi) in length along the bank of the Tisza River and 60 kilometres (37 mi) in depth to the east of the Tisza River at Szolnok. The Romanian army undertook manoeuvres to the north of this Hungarian territory. Gen. Davidoglu, commanding the 2nd Cavalry Division, formed closest to the river. Gen. Obogeanu, commanding the 1st Infantry Division, formed in the center and Gen. Olteanu, commanding the 6th Infantry Division, formed furthest to the east.

Romanian counterattack

On 24 July, the Romanian Army's northern maneuver group attacked. Elements of the 2nd Cavalry Division, supported by troops of the 18th Infantry Division, took Kunhegyes. The Romanian 1st Infantry Division attacked the Hungarian 6th Infantry Division and took Fegyvernek. The Romanian 6th Ddivision was less successful, being counterattacked on the left flank by the Hungarian reserve formations. Altogether, the attack pushed back the Hungarian army 20 kilometres (12 mi). Romanian forces were supported by the 2nd Vânători Division and some cavalry units when they became available.

On 25 July, fighting continued. Hungarian forces counterattacked at Fegyvernek, engaging the Romanian 1st Infantry Division. With their lines breaking, Hungarian troops began a retreat towards the Tisza River bridge at Szolnok. On 26 July, Hungarian forces destroyed the bridge. By the end of that day the east bank of the Tisza River was once again under Romanian control.

Romanian forces cross the Tisza River

_32.jpg)

After repelling the Hungarian attack, the Romanian army prepared to cross the Tisza River. The 7th Infantry Division returned from Bessarabia. The 2nd Infantry Division and some smaller infantry and artillery units also returned. The Romanian army massed 119 battalions (84,000 men), 99 artillery batteries with 392 guns and 60 cavalry squadrons (12,000 men). Hungarian forces continued an artillery bombardment.

From 27–29 July, the Romanian Army tested the strength of the Hungarian defense with small attacks. A plan was made to cross the Tisza River near Fegyvernek, where it makes a turn. On the night of 29–30 July, the Romanian Army crossed the Tisza River. Decoy operations were mounted at other points along the river, bringing intense artillery duels. Romanian forces held the element of surprise. On 31 July the Hungarian army retreated towards Budapest.

Romanian occupation of Budapest

Romanian forces continued their advance towards Budapest. On 3 August, under the command of General Gheorghe Rusescu, three squadrons of the 6th Cavalry Regiment of the 4th Brigade entered Budapest. Until midday on 4 August, 400 Romanian soldiers with two artillery guns held Budapest. Then the bulk of the Romanian troops arrived in the city and a parade was held through the city center in front of the commander, General Moşoiu. Romanian forces continued their advance into Hungary and stopped at Győr.

The incursion of Romania into Hungary caused the heaviest fighting of the war. The Romanian army casualties were 123 officers and 6,434 soldiers — 39 officers and 1,730 soldiers killed, 81 officers and 3,125 soldiers wounded, and three officers and 1,579 soldiers missing in action. As of 8 August, the Romanians forces had captured 1,235 Hungarian officers and 40,000 soldiers, seized 350 guns—including two with a caliber of 305 mm—332 machine guns, 52,000 rifles and 87 airplanes.

Aftermath

_36.jpg)

On 2 August, Kun fled Hungary towards the Austrian border and eventually reached the Soviet Union. A socialist government under the leadership of Gyula Peidl was installed in Budapest with the assistance of the Allied council, but its tenure was short-lived.

The counter-revolutionary White House Fraternal Association attempted to install Archduke Joseph August of Austria as Hungary's head of state and István Friedrich as prime minister. However, the Allied council would not accept a Habsburg as head of state in Hungary, and a new government was needed.

Romanian occupation of Hungary

Romania occupied all of Hungary with the exception of an area around Lake Balaton. There, Admiral Miklós Horthy formed a militia with arms from Romania.[27]:p. 612 Horthy was preparing to be Hungary's new leader at the end of the Romanian occupation. His supporters included some far-right nationalists.[37] Horthy's supporters also included members of the White Guards, who had persecuted Bolsheviks and Hungarian Jews, whom they perceived as a communist group given their disproportionate participation in Kun's government.[27]:p. 616[38]:p. 80–86 and 120. Horthy's nationalists and Romanian troops took steps to protect Hungary's Jewish people. The Romanian occupying force also took punitive actions against any revolutionary elements in areas under its control.[39]

Initially, Romanian troops provided policing and administrative services in occupied Hungary. Later, under pressure from the Allied council, these roles were returned to the Hungarians.[38]:p. 52However, in Budapest, only 600 carbines were provided to arm 3,700 policemen.

Romanian reparations

The Allied council was discontented with Romania's conduct during much of the Hungarian–Romanian war. Romania did not follow the Allied council's instructions, for example, by moving west of the Tisza River and by demanding large reparations.[40][41][38]:p. xxii and xxviii The Allied council decided that Hungary should pay war reparations in common with the Central Powers. The council pressured Romania to accept the supervision of an Inter-Allied Military Mission to oversee the disarmament of the Hungarian army and to see the Romanian troops withdraw.[38]:p. xxviii[27]:p. 614

The Inter-Allied Military Mission committee included General Harry Hill Bandholtz, who wrote a detailed diary of the events[38] Reginald Gorton, Jean César Graziani, and Ernesto Mombelli.[38]:p. 32 Lieutenant Colonel Guido Romanelli, Mombelli's secretary and former military representative of the Supreme Council in Budapest, was accused of being biased against Romania and was replaced.[27]:p. 616 The relationship between the Inter-Allied Military Mission and Romania was one of discord.[38]:p. 45[42]

The Allied council requested Romania not make its own requisition for reparations and to return any captured military assets.[27]:p. 615 The Inter-Allied Military Mission requested Romania return to Hungary the largely Hungarian-populated territory between the Tisza River and the first line of demarcation. Romania, under the leadership of Prime Minister Ion Brătianu, did not comply with the requests of the Inter-Allied Military Mission. On 15 November, the Allied council denied Romania reparations from Germany.[27]:p. 635 The outcome of the negotiations was that Bratianu resigned his prime ministership; Romania received 1 percent of the total reparations from Germany and limited amounts from Bulgaria and Turkey; Romania signed a peace treaty with Austria; Romania kept reparations from Hungary; and Romania's border with Hungary was determined.[27]:p. 646

Hungary saw the Romanian conditions of armistice as harsh. It saw the requisitioning of quotas of goods as looting.[27]:p. 614 She was also required to pay the expenses of the occupying troops. Romania sought to prevent Hungary from re-arming and retribution for the plunder of her land by the Central Powers during World War I.[22][43] Romania, having been denied by the Allied council, also sought compensation for its entire war effort. Under the terms of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye concerning Austria and the Treaty of Trianon concerning Hungary, Romania had to pay a "liberation fee" of 230 million gold francs to each. Romania also had to assume a share of the public debt of Austria-Hungary corresponding to the size of the former Austria-Hungary territories it now held.[27]:p. 646

In early 1920, Romanian troops departed Hungary. They took with them resources including foodstuffs, mineral ores and transportation and factory equipment[44] and also discovered historic bells of Romanian churches in Budapest taken by the Hungarians from Austro-Hungarian Army, which had not been melted by then.[45][46][47][48] Hungary ceded all war materials, except for the weapons necessary to arm the troops under Horthy's command. It handed to Romania her entire armament industry as well as 50% of the railway rolling stock (800 locomotives and 19,000 cars), 30 percent of all livestock, 30 percent of all agricultural tools and 35,000 wagons of cereals and fodder. The Allied council confiscated any goods taken by Romania after the 1918 Treaty of Bucharest.[49]

Controversy exists as to whether Romania's actions amounted to looting in terms of the volume and indiscriminate nature of goods removed from Hungary. Even private motor vehicles could be requisitioned.[38]:p. 131[43][50][49][51] Although public entities in occupied Hungary bore the brunt of the Romanian-imposed reparation quotas, where these were not enough the Romanian occupation authorities requisitioned quotes from private entities, including cattle, horses and grain from farms.[38]:p. 128[27]:pp. 612, 615–616

Order of battle

|

|

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hungarian-Romanian War of 1919. |

Notes

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015. McFarland. pp. 344–345. ISBN 9781476625850.

- Robert Paxton; Julie Hessler (2011). Europe in the Twentieth Century. CEngage Learning. p. 129. ISBN 9780495913191.

- Deborah S. Cornelius (2011). Hungary in World War II: Caught in the Cauldron. Fordham University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780823233434.

- Martin Kitchen (2014). Europe Between the Wars. Routledge. p. 190. ISBN 9781317867531.

- Ignác Romsics (2002). Dismantling of Historic Hungary: The Peace Treaty of Trianon, 1920 Issue 3 of CHSP Hungarian authors series East European monographs. Social Science Monographs. p. 62. ISBN 9780880335058.

- Dixon J. C. Defeat and Disarmament, Allied Diplomacy and Politics of Military Affairs in Austria, 1918–1922. Associated University Presses 1986. p. 34.

- Sharp A. The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking after the First World War, 1919–1923. Palgrave Macmillan 2008. p. 156. ISBN 9781137069689.

- Adrian Severin; Sabin Gherman; Ildiko Lipcsey (2006). Romania and Transylvania in the 20th Century. Corvinus Publications. p. 24. ISBN 9781882785155.

- Krizman B. The Belgrade Armistice of 13 November 1918 Archived 26 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine in The Slavonic and East European Review January 1970, 48:110.

- Roberts, P. M. (1929). World War I: A Student Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 1824. ISBN 9781851098798.

- Breit J. Hungarian Revolutionary Movements of 1918–19 and the History of the Red War in Main Events of the Károlyi Era Budapest 1929. pp. 115–116.

- Agárdy, Csaba (6 June 2016). "Trianon volt az utolsó csepp - A Magyar Királyság sorsa már jóval a békeszerződés aláírása előtt eldőlt". veol.hu. Mediaworks Hungary Zrt.

- Sachar H. M. Dreamland: Europeans and Jews in the Aftermath of the Great War. Knopf Doubleday 2007. p. 409. ISBN 9780307425676.

- Tucker S. World War I: the Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection ABC-CLIO 2014. p. 867. ISBN 9781851099658.

- Dowling T.C. Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO 2014 p. 447 ISBN 9781598849486.

- Andelman D. A. A Shattered Peace: Versailles 1919 and the Price We Pay Today. John Wiley and Sons 2009. p. 193 ISBN 9780470564721.

- John C. Swanson (2017). Tangible Belonging: Negotiating Germanness in Twentieth-Century Hungary. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780822981992.

- Robin Okey (2003). Eastern Europe 1740–1985: Feudalism to Communism. Routledge. p. 162. ISBN 9781134886876.

- John Lukacs (1990). Budapest 1900: A Historical Portrait of a City and Its Culture. Grove Press. p. 2012. ISBN 9780802132505.

- Diner D. Cataclysms: a History of the Twentieth Century from Europe's Edge University of Wisconsin Press 2008. p. 77.

- Michael S. Neiberg (2011). Arms and the Man: Military History Essays in Honor of Dennis Showalter. Brill Publishers. p. 156. ISBN 9789004206946.

- Lojko M. Meddling in Middle Europe: Britain and the 'Lands Between', 1919–1925 Central European University Press 2006.

- Mardarescu G.D. Campania pentru desrobirea Ardealului si ocuparea Budapestei (1918–1920) Cartea Romaneasca S.A., Bucuresti, 1922, p. 12.

- Treptow K. W. A History of Romania fourth edition. Center for Romanian Studies January 2003. ISBN 9789739432351.

- Iancu G. and Wachter M. The Ruling Council: the Integration of Transylvania into Romania (1918–1920) Center for Transylvanian Studies 1995. ISBN 9789739132787.

- Leadbeater, Chris (3 January 2019). "The forgotten war which made Transylvania Romanian". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Constantin Kirițescu. Istoria războiului pentru întregirea României. România Nouă, 1923 volume 2.

- Read A. The World on Fire Random House 2009. p. 161. ISBN 9781844138326.

- Eötvös Loránd University (1979). Annales Universitatis Scientiarum Budapestinensis de Rolando Eötvös Nominatae, Sectio philosophica et sociologica. 13–15. Universita. p. 141.

- Jack A. Goldstone (2015). The Encyclopedia of Political Revolutions. Routledge. p. 227. ISBN 9781135937584.

- Peter Pastor (1988). Revolutions and Interventions in Hungary and Its Neighbor States, 1918–1919. 20. Social Science Monographs. p. 441. ISBN 9780880331371.

- Peter F. Sugar; Péter Hanák; Tibor Frank (1994). A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. p. 308. ISBN 9780253208675.

- d'Esperey F. Archives diplomatiques. Europe Z, R 12 April 1919, 47. p. 86.

- Georges Clemenceau Archives diplomatiques. Europe Z, R 14 April 1919. 47. pp. 83–84.

- Köpeczi B. History of Transylvania: from 1830 to 1919 Social Science Monographs 2001. p. 791.

- World War I: A–D. ABC-CLIO 2005. vol 1. p. 563.

- Bodo B. Paramilitary Violence in Hungary after the First World War, East European Quarterly 22 June 2004.

- Bandholtz H. H. "An Undiplomatic Diary" AMS Press 1966. pp. 80–86.

- Sugar, P. F.; Hanák, P. (1994). A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. p. 310.

- Hoover H. The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson McGraw-Hill 1958 pp. 134–140.

- Thomas R. The Land of Challenge, a profile of the Magyars Southwest University Press 1998.

- Pastor, P. (1988). Revolutions and Interventions in Hungary and its Neighbour States, 1918–1919. Social Science Monographs. p. 313.

- A Country Study: Romania. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress.

- Slavicek, L. (2010). The Treaty of Versailles. Infobase Publishing. p. 84.

- Bichir, F. Lumea credintei, anul III, nr. 3(20).

- Ardeleanu, I.; Popescu-Puțuri, I.; Statului, A. (1986). Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică. p. 64.

- Revista Fundației Drăgan. (5–6). 1989, p. 79.

- Aioanei, V.; Ardeleanu, I. (1983). Desăvîrșirea unitătii național-statele a poporului român: Februarie 1920 – decembrie 1920. Științifică și Enciclopedică. p. 64.

- Eby C. D. (2007). Hungary at War: Civilians and Soldiers in World War II. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 4.

- Barclay, G. (1971).20th Century Nationalism.. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 26.

- MacMillan, M. (2002). Paris 1919, Six Months that Changed the World. New York: Random House. p. 268.

Bibliography

- Bachman, R., ed. (1991). "Greater Romania and the Occupation of Budapest". Romania: A Country Study. LOC. Washington: GPO. OCLC 470420391.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bandholtz, H. (1933). An Undiplomatic Diary. New York: Columbia University Press. OCLC 716592714.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barclay, G. (1971). 20th Century Nationalism. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9780297004783.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bernád, D.; et al. (2015). Magyar Warriors: The History of the Royal Hungarian Armed Forces, 1919–1945. 1. Warick: Helion. ISBN 9781906033880.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bodo, B. (2004). "Paramilitary violence in Hungary after the first world war". East European Quarterly. 38 (2): 129–172. ISSN 0012-8449.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Breit, J. (1925). "Main Events of the Károlyi Era". Hungarian Revolutionary Movements of 1918–19. 1. Budapest: Magy. Kir. OCLC 55974053.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Busky, D. (2002). Communism in History and Theory: The European Experience. Westport: Greenwood. ISBN 9780275977344.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eby, C. (2007). Hungary at War: Civilians and Soldiers in World War II. University Park: Penn State Press. ISBN 9780271040882.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grecu, D. (1995). "The Romanian military occupation of Hungary, April 1919 – March 1920". Romanian Postal History Bulletin. 5 (2): 14–35. OCLC 752328222.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Iancu, G.; et al. (1995). The Ruling Council: The Integration of Transylvania into Romania. Cluj-Napoca: Center for Transylvanian Studies. ISBN 9789739132787.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kiriţescu, C. (1924). Istoria războiului pentru întregirea României (in Romanian). 2. Bucharest: Romania Noua. OCLC 251736838.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lojkó, M. (2006). Meddling in Middle Europe: Britain and the 'Lands Between', 1919–1925. New York: CEU Press. ISBN 9789637326233.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacMillan, M. (2002). Paris 1919, Six Months that Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780375760525.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mardarescu, C. (2009). Campania pentru desrobirea Ardealului si ocuparea Budapestei, 1918–1920 (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Militară. ISBN 9789733207948.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitrasca, M. (2002). Moldova: A Romanian Province Under Russian Rule, Diplomatic History. New York: Algora. ISBN 9781892941862.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ormos, M. (1982). "Hungarian Soviet Republic and Intervention by the Entente". War and Society in East Central Europe. 6. Brooklyn College Press. OCLC 906429961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Treptow, K. (2003). A History of Romania (fourth ed.). Iasi: Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 9789739432351.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Webb, A. (2008). The Routledge Companion to Central and Eastern Europe since 1919. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781134065202.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)