Battle of Megiddo (1918)

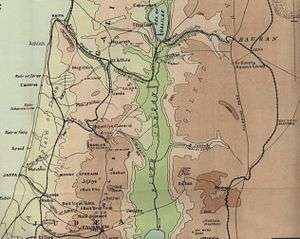

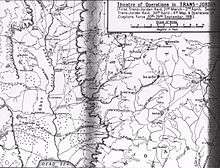

The Battle of Megiddo (Turkish: Megiddo Muharebesi) also known in Turkish as the Nablus Hezimeti ("Rout of Nablus"), or the Nablus Yarması ("Breakthrough at Nablus") was fought between 19 and 25 September 1918, on the Plain of Sharon, in front of Tulkarm, Tabsor and Arara in the Judean Hills as well as on the Esdralon Plain at Nazareth, Afulah, Beisan, Jenin and Samakh. Its name, which has been described as "perhaps misleading"[3] since very limited fighting took place near Tel Megiddo,[4] was chosen by Allenby for its biblical and symbolic resonance.[4]

The battle was the final Allied offensive of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War. The contending forces were the Allied Egyptian Expeditionary Force, of three corps including one of mounted troops, and the Ottoman Yildirim Army Group which numbered three armies, each the strength of barely an Allied corps. The series of battles took place in what was then the central and northern parts of Ottoman Palestine and parts of present-day Israel, Syria and Jordan. After forces of the Arab Revolt attacked the Ottoman lines of communication, distracting the Ottomans, British and Indian infantry divisions attacked and broke through the Ottoman defensive lines in the sector adjacent to the coast in the set-piece Battle of Sharon. The Desert Mounted Corps rode through the breach and almost encircled the Ottoman Eighth and Seventh Armies still fighting in the Judean Hills. The subsidiary Battle of Nablus was fought virtually simultaneously in the Judean Hills in front of Nablus and at crossings of the Jordan River. The Ottoman Fourth Army was subsequently attacked in the Hills of Moab at Es Salt and Amman.

These battles resulted in many tens of thousands of prisoners and many miles of territory being captured by the Allies. Following the battles, Daraa was captured on 27 September, Damascus on 1 October and operations at Haritan, north of Aleppo, were still in progress when the Armistice of Mudros was signed ending hostilities between the Allies and Ottomans.

The operations of General Edmund Allenby, the British commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, achieved decisive results at comparatively little cost, in contrast to many offensives during the First World War. Allenby achieved this through the use of creeping barrages to cover set-piece infantry attacks to break a state of trench warfare and then use his mobile forces (cavalry, armoured cars and aircraft) to encircle the Ottoman armies' positions in the Judean Hills, cutting off their lines of retreat. The irregular forces of the Arab Revolt also played a part in this victory.

Background

The ancient fortress of Megiddo stands on Tell el-Mutesellim (Tel Megiddo), at the mouth of the Musmus Pass near al-Lajjun, controlling the routes to the north and the interior by dominating the Plain of Armageddon or of Megiddo. Across this plain several armies, from the ancient Egyptians to the French under Napoleon, had fought on their way towards Nazareth in the Galilean Hills. By 1918 this plain, known as the Plain of Esdraelon (the Jezreel Valley in Israeli terms) was still strategically important as it linked the Jordan Valley and the Plain of Sharon 40 miles (64 km) behind the Ottoman front line, and together, these three valleys formed a semicircle round the main Ottoman positions in the Judean Hills held by their Seventh and Eighth Armies.[5][6]

Allied situation

The Entente Powers had declared war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914. In early 1915 and in August 1916 the Ottomans, with German commanders, aid and encouragement, had attacked the Suez Canal, a vital link between Britain and India, Australia and New Zealand. Under General Archibald Murray, the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) stopped the Ottoman army at the Battle of Romani and drove them back to Magdhaba and across the Sinai to Rafa to reoccupy Egyptian territory and secure the safety of the Suez Canal. Having constructed a railway and water pipeline across the desert, Murray then attacked southern Palestine. In the First Battle of Gaza and the Second Battle of Gaza in March and April 1917, the British attacks were defeated.

In 1916, the Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule had broken out in the Hejaz, led by Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca. Although the Ottomans defended Medina, at the end of the Hejaz Railway against them, part of the Sherifian Army, led by Hussein's son, the Emir Feisal, and British liaison officer T. E. Lawrence, extended the revolt northwards. Finally, Lawrence and bedouin tribesmen won the Battle of Aqaba in July 1917. The capture of the port of Aqaba allowed the Allies to supply Feisal's forces and deprived the Ottomans of a position behind the right flank of the EEF.

General Edmund Allenby had been appointed to succeed Murray in command of the EEF, and was encouraged to renew the offensive. After receiving reinforcements, he broke through the Ottoman defences in the Third Battle of Gaza and defeated an Ottoman attempt to make a stand to the north at the Battle of Mughar Ridge. Despite Ottoman counter-attacks, the EEF captured Jerusalem in the second week in December 1917.

After a pause of several weeks caused by bad weather and the need to repair his lines of communication, Allenby advanced eastward to capture Jericho in February 1918. However, in March, the Germans launched their Spring Offensive on the Western Front, intending to defeat the Allied armies in France and Belgium. Allenby was ordered to send reinforcements (two complete divisions, another 24 infantry battalions from other divisions and nine dismounted yeomanry regiments) to the Western Front.[7] Allenby's tank force was also returned to France.[8] In total approximately 60,000 officers and men were transferred to the Western Front in 1918.[9]

However, Allenby maintained pressure on the Ottoman armies by twice sending mounted and infantry divisions across the Jordan. The first attack briefly cut the Hejaz Railway near Amman before the attackers retreated. In the second attack, Allenby's troops captured Es Salt on the road to Amman, but fell back when their communications were threatened. Despite these failures, Allenby had established two bridgeheads across the Jordan north of the Dead Sea which were retained during the ensuing occupation of the southern Jordan Valley.[10]

Ottoman situation

At the same time (effectively from 8 March), the Ottoman command changed.[11] The highest level Ottoman headquarters in Palestine was the Yıldırım Army Group. The Army Group had originally been formed to recapture Baghdad which had been captured by the British in March 1917. Instead, it had been diverted to Palestine where the British were close to capturing Jerusalem. The Army Group's commander was the German General Erich von Falkenhayn, who wished to continue a policy of "yielding defence" rather than hold positions at all costs. He was also prepared to retreat to shorten his lines of communication and reduce the need for static garrisons. However, he was unpopular among Ottoman officers, mainly because he relied almost exclusively on German rather than Turkish staff officers, and was blamed for the defeats at Gaza and Jerusalem.[12] He was replaced by another German General, Otto Liman von Sanders, who had commanded the Ottoman defence during the Gallipoli Campaign.[11] Liman reasoned that continued retreat in Palestine would demoralise the troops, ruin their draught animals, encourage the Arab Revolt to spread further north into the Ottoman rear areas and also lead to all the Ottoman forces to the south in the Hejaz being finally isolated.[13] His forces halted their retreat and dug in to resist the British, even reoccupying some ground near the Jordan as Allenby's two raids across the Jordan were repulsed.[14]

Until late September 1918, the strategic situation of the Ottoman Empire appeared to be better than that of the other Central Powers. Their forces in Mesopotamia were holding their ground, while in the Caucasus they had captured Armenia, Azerbaijan and much of Georgia in an advance towards the Caspian Sea. Liman von Sanders was expected to repeat his defence of Gallipoli and defeat the British invasion in Palestine.[15]

However, some other commanders were worried about an assault on their extended front in Palestine. They wished to pull their troops back, so an attack would have to cross undefended ground and lose any tactical surprise. However, Liman would have had to abandon what seemed to be good defences and decided that it was too late to pull back.[16]

Allied reorganisation

During the summer of 1918, Allenby's forces were built back up to full strength. Two British Indian Army cavalry divisions, the 4th Cavalry Division and 5th Cavalry Division, arrived from the Western Front and were reorganised to include one British yeomanry regiment in five of their six brigades.[17] Two Indian infantry divisions, the 3rd (Lahore) Division and the 7th (Meerut) Division, were transferred from the Mesopotamian Campaign to replace two divisions which had been sent to the Western Front.[17] Four of Allenby's infantry divisions (the 10th, 53rd, 60th and 75th) were reformed on the pattern of British Indian Army, with three Indian and one British infantry battalion in each brigade[18] except one brigade in the 53rd Division which had one British, one South African and two Indian battalions.[19] The remaining British infantry division, the 54th (East Anglian) Division, retained its all-British composition, although the brigade-sized Détachement Français de Palestine et de Syrie was attached to the division.[18]

There was a comparative lull in activity while Allenby's divisions were reorganised and retrained, but some local attacks were made, especially in the Judean Hills. On 19 July, the Ottomans and Germans mounted a brief attack at Abu Tellul near the Jordan, but were defeated by Australian Light Horse regiments with heavy casualties to the German 11th Reserve Jäger battalion, which was subsequently withdrawn from Palestine.[20]

Arab Northern Army

As Allenby's reorganisation proceeded, the Arab Northern Army (part of the Arab Revolt) was operating east of the Jordan under the overall leadership of the Emir Feisal. Feisal's headquarters were at Aba el Lissan, about 15 miles (24 km) south-west of the Ottoman position at Ma'an, and his army received support from the British through the port of Aqaba. Assistance to Feisal included liaison officers, detachments of armoured cars, Indian machine gunners and a French Algerian mountain battery,[21] 2,000 camels from three disbanded battalions of the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade,[22] weapons, ammunition and above all, money (almost always in coin). In mid-1916, this had started as a monthly subsidy of £30,000. By the time Allenby launched his Megiddo offensive, it had grown to £220,000 a month.[23]

The 2,000[24] regular soldiers of the Arab Northern Army maintained a blockade of the Ottoman garrison at Ma'an after an unsuccessful attack at Al-Samna earlier in the year.[25] They were commanded by Jaafar Pasha, formerly an Ottoman officer who had been sent to lead a rebellion against the British by the Senussi in Egypt, but had joined the Arab Revolt after being captured. Most of these regulars were former Arab conscripts in the Ottoman Army who had deserted or, like Jaafar, had changed sides after becoming prisoners of war.[26]

Meanwhile, Arab irregulars raided the Hejaz Railway from Aba-el-Lissan and Aqaba, often accompanied by Lawrence and other British liaison officers.[27] In particular, in the weeks following the failure of Allenby's second attack across the Jordan, they carried out demolitions on an 80 miles (130 km) stretch of line around Mudawara, due east of Aqaba, effectively closing the line for a month and ending Ottoman operations around Medina at the end of the railway.[28]

I do not for one moment denigrate the good name of Lawrence, nor detract from his leadership in the 'Arab Revolt' in Arabia in harassing the Turks, blowing up trains, etc. but when it came to co–operation with Allenby's forces, the Arabs under Lawrence had in my experience, nuisance value only.

— Rex Hall 5th Light Horse Brigade[29]

Prelude

Allenby's plan

Allenby intended to break through the western end of the Ottoman line, where the terrain was favourable to cavalry operations. His horsemen would pass through the gap to seize objectives deep in the Ottoman rear areas and isolate their Seventh and Eighth Armies.[30]

As a preliminary move, the Arab Northern Army would attack the railway junction at Daraa beginning on 16 September, to interrupt the Ottoman lines of communication and distract the Yildirim headquarters.[31][32]

The two divisions of XX Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Philip Chetwode, would make an attack in the Judean Hills beginning on the night of 18 September, partly to further distract Ottoman attention to the Jordan Valley sector, and partly to secure positions from which their line of retreat across the Jordan could be blocked.[13] Once the main offensive by XXI Corps and the Desert Mounted Corps was launched, XX Corps was to block the Ottoman escape route from Nablus to the Jordan crossing at Jisr ed Damieh and if possible capture the Ottoman Seventh Army's headquarters in Nablus.[33][34][35]

The main breakthrough was to be achieved on the coast on 19 September by four infantry divisions of XXI Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Edward Bulfin, massed on a front 8 miles (13 km) wide. The fifth division of XXI Corps (the 54th) was to make a subsidiary attack 5 miles (8.0 km) inland of the main breach.[13] Once the breakthrough was achieved, the corps, with the 5th Light Horse Brigade attached, would advance to capture the headquarters of the Ottoman Eighth Army at Tulkarm and the lateral railway line by which the Ottoman Seventh and Eighth Armies were supplied, including the important railway junction at Messudieh.[31][34][36]

The strategic move was to be made by the Desert Mounted Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Harry Chauvel. Its three mounted divisions were massed behind the three westernmost infantry divisions of XXI Corps. As soon as XXI Corps had breached the Ottoman defences, they were to march north to reach the passes through the Carmel Range before Ottoman troops could forestall them, and pass through these to seize the communication centres of Al-Afuleh and Beisan. These two communication centres were within the 60 miles (97 km) radius of a strategic cavalry "bound", the distance mounted units could cover before being forced to halt for rest and to obtain water and fodder for the horses. If they were captured, the lines of communication and retreat for all Ottoman troops west of the Jordan would be cut.[30]

Finally, a detachment consisting of the Anzac Mounted Division, the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade, two battalions of the British West Indies Regiment, and two battalions of Jewish Volunteers in the Royal Fusiliers, amounting to 11,000 men[37][38] commanded by Major General Edward Chaytor and known as Chaytor's Force, was to capture the Jisr ed Damieh bridge and fords in a pincer movement. This important line of communication between the Ottoman Armies on the west bank of the Jordan with the Ottoman Fourth Army at Es Salt, was required by Allenby before Chaytor could proceed to capture Es Salt and Amman.[36][39]

Entente deceptions

Secrecy was an essential part, as it had been at the Battle of Beersheba the preceding year. It was feared that the Ottomans could thwart the preparations for the attack by making a withdrawal in the coastal sector.[40] Laborious efforts were therefore made to prevent the Ottomans discerning Allenby's intentions and to persuade them that the next Entente attack would be made in the Jordan Valley. All westward movements of personnel and vehicles from the Jordan Valley towards the Mediterranean coast were made during the night while all movements eastwards were made during daytime. The detached Anzac Mounted Division in the Jordan Valley simulated the activity of the entire mounted corps. Troops marched openly down to the valley by day, and were secretly taken back by lorry at night to repeat the process the next day. Vehicles or mules dragged harrows along tracks to raise dust clouds, simulating other troop movements. Dummy camps and horse lines were constructed and a hotel in Jerusalem was ostentatiously commandeered for an Expeditionary Force headquarters.[13][41][42]

Meanwhile, the 2nd (British) Battalion of the Imperial Camel Corps joined Arab irregulars in a raid east of the Jordan. They first captured and destroyed the railway station at Mudawara, finally cutting the Hejaz Railway,[43] and then mounted a reconnaissance near Amman, scattering corned beef tins and documents as proof of their presence.[44] Lawrence sent agents to openly buy up huge quantities of forage in the same area.[13] As a final touch, British newspapers and messages were filled with reports of a race meeting to take place on 19 September, the day on which the attack was to be launched.[45]

Though Allenby's deceptions did not induce Liman to concentrate his forces against the River Jordan flank,[46] Allenby was nevertheless able to concentrate a force superior to the Ottoman XXII Corps by nearly five to one in infantry and even more in artillery on the Mediterranean flank, where the main attack was to be made, undetected by the Ottomans.[13] Earlier in the year (on 9 June), units of the 7th (Meerut) Division had captured two hills just inland from the coast, depriving the Ottomans of two important observation points overlooking the Allied bridgehead north of the Nahr-el-Auja.[47] Also, the Royal Engineers had established a bridging school on the Nahr-al-Auja much earlier in the year, so the sudden appearance of several bridges across it on the eve of the assault did not alert any other Ottoman observers.[48]

Entente air superiority

These various deceptions could not have been successful without the Entente forces' undisputed air supremacy west of the Jordan. The squadrons of the Royal Air Force and the Australian Flying Corps outnumbered and outclassed the Ottoman and German aircraft detachments in Palestine.[48] During the weeks before the September attack, enemy aerial activity dropped markedly. Although during one week in June hostile aeroplanes crossed the British front lines 100 times, mainly on the tip–and–run principle at altitudes of 16,000–18,000 feet (4,900–5,500 m), by the last week in August this number had dropped to 18 and during the three following weeks of September it was reduced to just four enemy aircraft. During the 18 days before the start of the battle, only two or three German aircraft were seen flying.[49] Eventually, Ottoman and German reconnaissance aircraft could not even take off without being engaged by British or Australian fighters,[13] and could therefore not see through Allenby's deceptions, nor spot the true Allied concentration which was concealed in orange groves and plantations.

Ottoman dispositions

Under the Yildirim Army Group were, from west to east: the Eighth Army (Jevad Pasha) which held the front from the Mediterranean coast to the Judean Hills with five divisions (one of which had recently arrived at Et Tire, a few miles behind the front lines), a cavalry division and the German "Pasha II" detachment, equivalent to a regiment; the Seventh Army (Mustafa Kemal Pasha) which held the front in the Judean Hills to the Jordan River with four divisions and a German regiment; and the Fourth Army (Jemal Mersinli Pasha), which was divided into two groups: one faced the bridgeheads which Allenby's forces had seized over the Jordan with two divisions, while the other defended Amman and Ma'an and the Hejaz Railway against attacks by Arab forces with two divisions, a cavalry division and some miscellaneous detachments.[50]

In August 1918, the Yildirim Army Group's front-line strength was 40,598 infantrymen armed with 19,819 rifles, 273 light and 696 heavy machine guns,[51] and 402 guns.[1]

Although the Ottomans had fairly accurately estimated the total Allied strength, Liman lacked intelligence on the Allied plans and dispositions and was forced to dispose his forces evenly along the entire length of his front. Moreover, almost his entire fighting strength was in the front line. The armies' only operational reserves were the two German regiments and the two understrength cavalry divisions. Further back there were no strategic reserves other than some "Depot Regiments", not organised as fighting units, and scattered garrisons and line of communication units.

After four years of warfare, most Ottoman units were understrength and demoralised by desertions, sickness and shortage of supplies (although supplies were not short at Damascus when Desert Mounted Corps arrived there on 1 October 1918. It was possible to find food and forage for three cavalry divisions; 20,000 men and horses "without depriving the inhabitants of essential food."[52]). Liman nevertheless relied on the determination of the Turkish infantry and the strength of their front-line fortifications.[51] Although the numbers of artillery pieces and especially of machine guns among the defenders were unusually high, the Ottoman lines had only thin belts of barbed wire compared with those on the Western Front,[53] and Liman was unable to take into account the improved British tactical methods in set-piece offensives, involving surprise and short but accurate artillery preparation based on aerial reconnaissance.[54]

Battle

Opening attacks

On 16 September 1918, Arabs under T. E. Lawrence and Nuri as-Said began destroying railway lines around the vital rail centre of Daraa, at the junction of the Hedjaz Railway which supplied the Ottoman army at Amman and the Palestine Railway which supplied the Ottoman armies in Palestine. Lawrence's initial forces (a Camel Corps unit from Feisal's Army, an Egyptian Camel Corps unit, some Gurkha machine gunners, British and Australian armoured cars and French mountain artillery) were soon joined by up to 3,000 Ruwallah and Howeitat tribesmen under noted fighting chiefs such as Auda abu Tayi and Nuri es-Shaalan. Although Lawrence was ordered by Allenby only to disrupt communications around Daraa for a week and Lawrence himself had not intended a major uprising to take place in the area immediately, to avoid Ottoman reprisals, a growing number of local communities spontaneously took up arms against the Turks.[55][56]

As the Ottomans reacted, sending the garrison of Al-Afuleh to reinforce Daraa,[57] the units of Chetwode's Corps made attacks in the hills above the Jordan on 17 and 18 September. The 53rd Division attempted to seize ground commanding the road system behind the Ottoman front lines. Some objectives were captured but a position known to the British as "Nairn Ridge" was defended by the Ottomans until late on 19 September. Once it was captured, roads could be constructed to link the British road systems with those newly captured.[58]

At the last minute, an Indian deserter had warned the Turks about the impending main attack. Refet Bey, the commander of the Ottoman XXII Corps on the Eighth Army's right flank, wished to withdraw to forestall the attack but his superiors Jevad Pasha, commanding the Ottoman Eighth Army, and Liman (who feared that the deserter was himself an attempted intelligence bluff) forbade him to do so.[13][56]

At 1:00am on 19 September, the RAF Palestine Brigade's single Handley Page O/400 heavy bomber dropped its full load of sixteen 112-pound (51 kg) bombs on the main telephone exchange and railway station in Al-Afuleh. This cut communications between Liman's headquarters at Nazareth and Ottoman Seventh and Eighth Armies for the following vital two days, dislocating the Ottoman command.[59][60][61] DH.9s of No. 144 Squadron also bombed El Afule telephone exchange and railway station, Messudieh railway junction and the Ottoman Seventh Army headquarters and telephone exchange at Nablus.[62][63][64]

Breakthrough of Ottoman line

At 4:30am, Allenby's main attack by XXI Corps opened. A barrage by 385 guns (the field artillery of five divisions, five batteries of 60-pounder guns, thirteen siege batteries of medium howitzers and seven batteries of the Royal Horse Artillery),[65] 60 trench mortars and two destroyers off the coast fell on the Ottoman 7th and 20th Divisions' front-line positions defending Nahr el Faliq.[65] As the opening bombardment turned to a "lifting" barrage at 4:50am, the British and Indian infantry advanced and quickly broke through the Ottoman lines.[53] Within hours, the Desert Mounted Corps were moving north along the coast, with no Ottoman reserves available to check them.

From 10.00 hours onwards, a hostile aeroplane observer, if one had been available, flying over the Plain of Sharon would have seen a remarkable sight – ninety–four squadrons, disposed in great breadth and in great depth, hurrying forward relentlessly on a decisive mission – a mission of which all cavalry soldiers have dreamed, but in which few have been privileged to partake.

— Lieutenant Colonel Rex Osborn in The Cavalry Journal.[66]

According to Woodward, "concentration, surprise, and speed were key elements in the blitzkrieg warfare planned by Allenby."[67] By the end of the first day of battle, the left flank unit of the British XXI Corps (the 60th Division) had reached Tulkarm[68] and the remnants of the Ottoman Eighth Army were in disorderly retreat under air attack by Bristol F.2 Fighters of No. 1 Australian Squadron, through the defile at Messudieh and into the hills to the east, covered by a few hastily organised rearguards. Jevad Pasha, the army commander, had fled, and Mustafa Kemal Pasha at Seventh Army headquarters was unable to re-establish control over Eighth Army's troops.

Throughout the day, the RAF prevented any of the German aircraft based at Jenin from taking off and interfering with the British land operations. Relays of two S.E.5s from Nos. 111 and 145 Squadrons, armed with bombs, circled over the German airfield at Jenin all day on 19 September. Whenever they spotted any movement on the ground, they bombed the airfield. Each pair of aircraft were relieved every two hours, machine-gunning the German hangars before departing.[69]

Encirclement of two Ottoman Armies

During the early hours of 20 September 1918, the Desert Mounted Corps secured the defiles of the Carmel Range. The 4th Mounted Division passed through these to capture Afulah and Beisan, complete with the bulk of two depot regiments. A brigade of the 5th Mounted Division attacked Nazareth, where Liman von Sanders's HQ was situated, although Liman himself escaped. In the late afternoon a brigade from the Australian Mounted Division occupied Jenin, capturing many retreating Ottomans. The 15th Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade, of the 5th Mounted Division, captured the port of Haifa on 23 September.[68][70]

Once nothing stood between Allenby's forces and Mustafa Kemal's Seventh Army in Nablus, Kemal decided that he lacked sufficient men to fight the British forces.[71] With the railway blocked, the Seventh Army's only escape route lay to the east, along the Nablus-Beisan road that led down the Wadi Fara into the Jordan valley.[72]

_Destroyed_Turkish_transport.jpg)

On the night of 20–21 September the Seventh Army began to evacuate Nablus.[72] By this time it was the last formed Ottoman army west of the Jordan and although there was a chance that Chetwode's XX Corps might cut off their retreat, its advance had been slowed by Ottoman rearguards. On 21 September, the Seventh Army was spotted by aircraft in a defile west of the river. The RAF proceeded to bomb the retreating army and destroyed the entire column. Waves of bombing and strafing aircraft passed over the column every three minutes and although the operation had been intended to last for five hours, the Seventh Army was routed in 60 minutes. The wreckage of the destroyed column stretched over 6 miles (9.7 km). British cavalry later found 87 guns, 55 motor-lorries, 4 motor-cars, 75 carts, 837 four-wheeled wagons, and scores of water-carts and field-kitchens destroyed or abandoned on the road.[73] Many Ottoman soldiers were killed and the survivors were scattered and leaderless. Lawrence later wrote that "the RAF lost four killed. The Turks lost a corps."[74]

According to Chauvel's biographer, Allenby's plan for the Battle of Megiddo was as "brilliant in execution as it had been in conception; it had no parallel in France or on any other front, but rather looked forward in principle and even in detail to the Blitzkrieg of 1939."[75] Over the next four days, the 4th Cavalry Division and Australian Mounted Division rounded up large numbers of demoralised and disorganised Ottoman troops in the Jezreel Valley. Many of the surviving refugees who crossed the Jordan were attacked and captured by Arabs as they approached or tried to bypass Daraa.

Liman deployed a rearguard to hold Samakh, on the Sea of Galilee. This town was to be the centre of a line stretching from Lake Hula to Daraa. A charge by one and a half Australian Light Horse regiments before dawn on 25 September, followed by intense hand-to-hand fighting, eventually captured the town. This victory broke the proposed defensive line and ended the Battle of Sharon.[76][77]

Judean Hills fighting

As the Desert Mounted Corps and XXI Corps achieved their objectives, the units of XX Corps resumed their advance. Nablus was captured about noon on 21 September by the 10th Division and the Australian 5th Light Horse Brigade from XXI Corps. The British 53rd Division halted its advance towards the Wadi el Fara road when it became clear that the retreating Ottomans had effectively been destroyed by aerial attacks.

Later operations around Daraa

German and Turkish aircraft had continued to operate from Daraa, harassing the Arab irregulars and insurgents still attacking railways and isolated Ottoman detachments about the town. At Lawrence's urging, British aircraft began operating from makeshift landing strips at Um el Surab nearby from 22 September. Three Bristol F.2 Fighters shot down several of the German aircraft. The Handley Page 0/400 ferried across petrol, ammunition and spares for the fighters and two Airco DH.9s, and itself bombed the airfield at Daraa early on 23 September and nearby Mafraq on the following night.[78]

Capture of Amman

On 22 September, on the western side of the Jordan River, the Ottoman 53rd Division was attacked at its headquarters near the Wadi el Fara road, by units from Meldrum's Force. This force consisted of the New Zealand Mounted Brigade (commanded by Brigadier General W. Meldrum), the Machine Gun Squadron, the mounted sections of the 1st and 2nd British West Indies Regiment, the 29th Indian Mountain Battery and Ayrshire (or Inverness) Battery RHA. Meldrum's force captured the commander of the 53rd Division, its headquarters and 600 prisoners, before defeating determined Ottoman rearguards to capture the Jisr ed Damieh bridge.[79][80][81][82]

The Ottoman Fourth Army had remained in its positions until 21 September, apparently unaware of the destruction of the Ottoman armies west of the Jordan until refugees reached them. That day, Liman ordered the Fourth Army to retreat to Daraa and Irbid, about 18 miles (29 km) to the west. The Fourth Army began to retreat from the Jordan and Amman on 22 September in increasing disorder due to attacks by British and Australian aircraft on 23 September which caused heavy casualties to the retreating troops on the roads between Es Salt and Amman. On the same day, Chaytor's Force advanced across the Jordan River to capture Es Salt.[83][84]

On 25 September the Ottoman troops who had reached Mafraq by train from Amman, but who could proceed no further because the railway ahead was demolished, came under heavy aerial attack which caused many casualties and much disorder. Many Ottoman soldiers fled into the desert but several thousand maintained some order and, having abandoned their wheeled transport, continued to retreat northwards towards Daraa on foot or horseback, under constant air attack.[83]

Chaytor's Force captured Amman on 25 September.[80] The Ottoman detachment from Ma'an, also trying to retreat northwards, found its line of retreat blocked at Ziza, south of Amman, and surrendered intact to the Anzac Mounted Division on 28 September, rather than risk slaughter by Arab irregulars.[84][85]

I desire to convey to all ranks and all arms of the Force under my command, my admiration and thanks for their great deeds of the past week, and my appreciation of their gallantry and determination, which have resulted in the total destruction of the VIIth and VIIIth Turkish Armies opposed to us. Such a complete victory has seldom been known in all the history of war.

— E. H. H. Allenby General Commander in Chief EEF 26 September 1918[86]

Aftermath

Capture of Damascus

Allenby now ordered his cavalry to cross the Jordan, to capture Daraa and Damascus. Meanwhile, the 3rd (Lahore) Division advanced north along the coast towards Beirut and the 7th (Meerut) Division advanced on Baalbek in the Beqaa Valley, where the rearmost Ottoman depots and reinforcement camps were situated.

On 27 September, the 4th Mounted Division moved to Daraa, which had already been abandoned to Arab forces, and then advanced north on Damascus in company with them. The retreating Ottomans committed several atrocities against hostile Arab villages; in return, the Arab forces took no prisoners. Almost an entire Ottoman brigade (along with some German and Austrians) was massacred near the village of Tafas on 27 September, with the commander Jemal Pasha narrowly escaping. The Arabs repeated the performance the next day, losing a few hundred casualties while wiping out nearly 5,000 Turks in these two battles.

The 5th Mounted and Australian Mounted Divisions advanced directly across the Golan Heights towards Damascus. They fought actions at Benat Yakup, Kuneitra, Sasa and Katana, before they reached and closed the north and north-west exits from Damascus on 29 September.[87] On 30 September, the Australians intercepted the garrison of Damascus as they tried to retreat through the Barada gorge. Damascus was captured the next day, with the Allies capturing 20,000 prisoners.[88] Jemal Pasha fled, having failed to inspire last-ditch resistance.

Overall, the campaign to the fall of Damascus resulted in the surrender of 75,000 Ottoman soldiers.[88]

Pursuit to Aleppo

After the fall of Damascus, the 5th Mounted Division and some detachments of the Arab Northern Army advanced north through Syria, capturing Aleppo on 26 October. They subsequently advanced to Mouslimmiye, where Mustafa Kemal (who had replaced Liman von Sanders in command of the Yıldırım Army Group) had rallied some troops under XXII Corps HQ. Kemal held his positions until 31 October, when hostilities ceased following the signing of the Armistice of Mudros.

Effects

The successful action at Megiddo resulted in the battle honour "Megiddo" being awarded to units of the British, Dominion and Empire forces participating in the battle. Battle honours for the two subsidiary battles of Sharon and Nablus were also awarded.[89]

Edward Erickson, a historian of the Ottoman Army, later wrote:

The Battle of the Nablus Plain ranks with Ludendorff's Black Days of the German Army in the effect that it had on the consciousness of the Turkish General Staff. It was now apparent to all but the most diehard nationalists that the Turks were finished in the war. In spite of the great victories in Armenia and in Azerbaijan, Turkey was now in an indefensible condition, which could not be remedied with the resources on hand. It was also apparent that the disintegration of the Bulgarian Army at Salonika and the dissolution of the Austro–Hungarian Army spelled disaster and defeat for the Central Powers. From now until the Armistice, the focus of the Turkish strategy would be to retain as much Ottoman territory as possible.[90]

Notes

- Liddell Hart, p.432 fn

- Cutlack 1941 p. 168

- Christopher Catherwood (22 May 2014). The Battles of World War I. Allison & Busby. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7490-1502-2.

- Alan Warwick Palmer (December 2000). Victory 1918. Grove Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-8021-3787-6.

- Gullett 1919 pp. 25–6

- Hill 1978 pp. 162–3

- Falls 1930 Vol 2 Part I pp. 184–291, 302–9, Part II pp. 411–21

- Perrett 1999, p. 16

- Bruce 2002, p. 204

- Falls 1930 Vol 2 Part I pp. 328–49, 364–394, Part II pp. 422–38

- Erickson 2001, p.194

- Erickson 2001, p.193

- Liddell Hart, p.437

- Erickson 2001, p.195

- Erickson 2001 p. 179

- Grainger 2006 p. 234

- Perrett 1999, p.24

- Hanafin, James. "Order of Battle of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, September 1918" (PDF). orbat.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "53rd (Welsh) Division". The Long Long Trail. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- Bruce 2002, p. 208

- Wavell 1968 pp. 199–200

- Lawrence, p.141

- Hughes, p.23

- Murphy, David (2008). The Arab Revolt 1916–18. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-339-1.

- Lawrence, pp.532–533; Murphy, pp.68, 73

- Hughes, pp.20–21

- Lawrence, pp.531–538

- Lawrence, pp.545–548

- Hall 1975 pp. 120–1

- Liddell Hart, p.435

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 448

- Wavell pp. 199–200

- Maunsell p.213

- Carver 2003 p. 232

- Bruce p. 216

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 Part II pp. 455–6

- Jukes, p.307

- Kinloch, p.321

- Allenby 24 July 1918 in Hughes 2004 pp. 168–9

- Lawrence, p.554

- Downes 1938 p. 716

- Powles 1922 p. 234

- Lawrence, p.570

- Lawrence, pp.589–590

- Paget 1994 Vol. 5 pp. 255–7

- Erickson 2007, pp.134–135

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2, pp. 425–6

- Falls (1964), p.39

- Cutlack pp. 133, 146–147

- Erickson 2001, p.197

- Erickson 2001, p.196

- Preston 1921 pp. 322–3

- Erickson 2001, p. 198

- Erickson 2001, p.200

- Lawrence, pp.618–19

- Erickson 2001 p. 198

- Lawrence, pp.623–24

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 471–2, 488–491

- Baker 2003, p.134

- Cutlack p. 152

- Liddell Hart, p.436

- Cutlack pp. 151–2

- Carver 2003 p. 225, 232

- Maunsell 1926 p.213

- Falls, p.37

- Woodward p. 195

- Woodward 2006 p. 191

- Liddell Hart, p.438

- Baker 2003, pp.134–35

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 529–32, 532–7

- Mango 2002, p.180

- "Battle of Megiddo, 19–25 September 1918". historyofwar.com. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- Cutlack, p.161

- Baker 2003, pp. 136–37

- Hill 1978 p. 173

- Falls 1964, p.88

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 542–5

- Lawrence, pp.638–640, 643

- Powles 1922 pp. 245–6

- Wavell 1968 p. 221

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 550

- Moore 1920 pp. 148–50

- Cutlack 1941 pp.165–167

- Falls 1964, pp.97–99

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 555–6

- Hughes 2004 p. 189

- "Campaign Summary and Notes on Horse Artillery in Sinai and Palestine" (PDF). Field Artillery Journal. May–June 1928. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- Liddell Hart, p.439

- Singh 1993, p. 166

- Erickson 2001 p.200

References

- Baker, Anne (2003). From Biplane to Spitfire: The Life of Air Chief Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond KCB KCMG DSO. Barnsley, Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 0-85052-980-8.

- Bruce, Anthony (2002). The Last Crusade: The Palestine Campaign in the First World War. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5432-2.

- Cutlack, Frederic Morley (1941). The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War, 1914–1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Volume VIII (11th ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 220900299.

- Downes, Rupert M. (1938). "The Campaign in Sinai and Palestine". In Butler, Arthur Graham (ed.). Gallipoli, Palestine and New Guinea. Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918. Volume 1 Part II (2nd ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 547–780. OCLC 220879097.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2001). Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31516-7.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2007). John Gooch; Brian Holden Reid (eds.). Ottoman Army Effectiveness in World War I: A Comparative Study. Cass Military History and Policy Series No. 26. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96456-9.

- Falls, Cyril (1930). Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from June 1917 to the End of the War. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Volume 2 Part I. A. F. Becke (maps). London: HM Stationery Office. OCLC 644354483.

- Falls, Cyril (1930). Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from June 1917 to the End of the War. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Volume 2 Part II. A. F. Becke (maps). London: HM Stationery Office. OCLC 256950972.

- Falls, Cyril (1964). Armageddon, 1918. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. ISBN 0-933852-05-3.

- Grainger, John D. (2006). The Battle for Palestine, 1917. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-263-8.

- Henry S. Gullett; Charles Barnet; David Baker, eds. (1919). Australia in Palestine. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 224023558.

- Hall, Rex (1975). The Desert Hath Pearls. Melbourne: Hawthorn Press. OCLC 677016516.

- Hill, Alec Jeffrey (1978). Chauvel of the Light Horse: A Biography of General Sir Harry Chauvel, GCMG, KCB. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. OCLC 5003626.

- Hughes, Matthew, ed. (2004). Allenby in Palestine: The Middle East Correspondence of Field Marshal Viscount Allenby June 1917 – October 1919. Army Records Society. 22. Phoenix Mill, Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3841-9.

- Jukes, Geoffrey (2003). The First World War: The War To End All Wars. Volume 2 of Essential Histories Specials. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 9781841767383.

- Kinloch, Terry (2007). Devils on Horses: In the Words of the Anzacs in the Middle East 1916–19. Auckland: Exisle Publishing. ISBN 978-0908988945.

- Mango, Andrew (2000). Ataturk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey. Woodstock, New York: Overlook Press. ISBN 9781585670116.

- Maude, Roderick (1998). The Servant, the General and Armageddon. Oxford: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-424-7.

- Murphy, David (2008). The Arab Revolt 1916–18: Lawrence Sets Arabia Ablaze. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-339-1.

- Lawrence, Thomas Edward (1926). Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Modern Classics. ISBN 0-14-001696-1.

- Liddell Hart, Basil Henry (1970). History of the First World War. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-23354-5.

- Paget, G.C.H.V Marquess of Anglesey (1994). Egypt, Palestine and Syria 1914 to 1919. A History of the British Cavalry 1816–1919. 5. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-395-9.

- Perrett, Bryan (1999). Megiddo 1918 – The Last Great Cavalry Victory. Osprey Military Campaign Series. 61. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-827-5.

- Powles, C. Guy; A. Wilkie (1922). The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine. Official History New Zealand's Effort in the Great War. Volume III. Auckland: Whitcombe & Tombs. OCLC 2959465.

- Preston, R.M.P. (1921). The Desert Mounted Corps: An Account of the Cavalry Operations in Palestine and Syria 1917–1918. London: Constable & Co. OCLC 3900439.

- Singh, Sarbans (1993). Battle Honours of the Indian Army 1757–1971. New Delhi: Vision Books. ISBN 81-7094-115-6.

- Woodward, David R. (2006). Hell in the Holy Land: World War I in the Middle East. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2383-7.

Further reading

- Cline, Eric H. (2000). The Battles of Armageddon: Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley from the Bronze Age to the Nuclear Age. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-09739-3.

- Lambden, Stephen (2000) [1999]. "Catastrophe, Armageddon and Millennium: Some Aspects of the Bábí-Bahá'í Exegesis of Apocalyptic Symbolism". Bahá'í Studies Review. 9. ISSN 2040-1701.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Megiddo (1918). |

- Daddis, Gregory (2005). "Armageddon's Lost Lesson's – Combined Arms Operations in Allenby's Palestine Campaign" (PDF). Air University Press.