South West Africa campaign

The South West Africa Campaign was the conquest and occupation of German South West Africa by forces from the Union of South Africa acting on behalf of the British imperial government at the beginning of the First World War.

| South West Africa campaign | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the African theatre of World War I | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Background

The outbreak of hostilities in Europe in August 1914 had been anticipated and government officials of South Africa were aware of the significance of their common border with the German colony. Prime Minister Louis Botha informed London that South Africa could defend itself and that the Imperial Garrison might depart for France; when the British government asked Botha whether his forces would invade German South West Africa, the reply was that they could and would.

South African troops were mobilised along the border between the two countries under the command of General Henry Lukin and Lt Col Manie Maritz early in September 1914. Shortly afterwards another force occupied the port of Lüderitz.

Boer Revolt

There was considerable sympathy among the Boer population of South Africa for the German cause. Only twelve years had passed since the end of the Second Boer War, in which Germany had offered the two Boer republics moral support against the British Empire. Lieutenant-Colonel Manie Maritz, heading commando forces on the border of German South West Africa, declared that

the former South African Republic and Orange Free State, as well as the Cape Province and Natal, are proclaimed free from British control and independent, and every [all] White inhabitant[s] of the mentioned areas, of whatever nationality, are hereby called upon to take their weapons in their hands and realise the long-cherished ideal of a Free and Independent South Africa.

— Manie Maritz.[3]

Maritz and several other high-ranking officers rapidly gathered forces with a total of about 12,000 rebels in the Transvaal and Orange Free State, ready to fight for the cause in what became known as the Boer Revolt (also sometimes referred to as the Maritz Rebellion).

The government declared martial law on 14 October 1914 and forces loyal to the government under the command of Generals Louis Botha and Jan Smuts proceeded to destroy the rebellion. Maritz was defeated on 24 October and took refuge with the Germans; the rebellion was suppressed by early February 1915. The leading Boer rebels received terms of imprisonment of six and seven years and heavy fines; two years later they were released from prison, as Botha recognised the value of reconciliation.

Combat between German and South African forces

A first attempt to invade German South West Africa from the south failed at the Battle of Sandfontein, close to the border with the Cape Colony, where on 26 September 1914 the German fusiliers inflicted a serious defeat on the British troops, although the survivors were left free to return to British territory.[4]

To disrupt South African plans to invade South West Africa, the Germans launched a pre-emptive invasion of their own. The Battle of Kakamas, between South African and German forces, took place over the fords at Kakamas, on 4 February 1915. It was a skirmish for control of two river fords over the Orange River between contingents of the German invasion force and South African armed forces. The South Africans succeeded in preventing the Germans gaining control of the fords and crossing the river.[5]

By February 1915, with the home front secure, the South Africans were ready to begin the complete occupation of the German territory. Botha in his military capacity as a senior and experienced military commander took command of the invasion. He split his command in two with Smuts commanding the southern forces while he took direct command of the northern forces.[6]

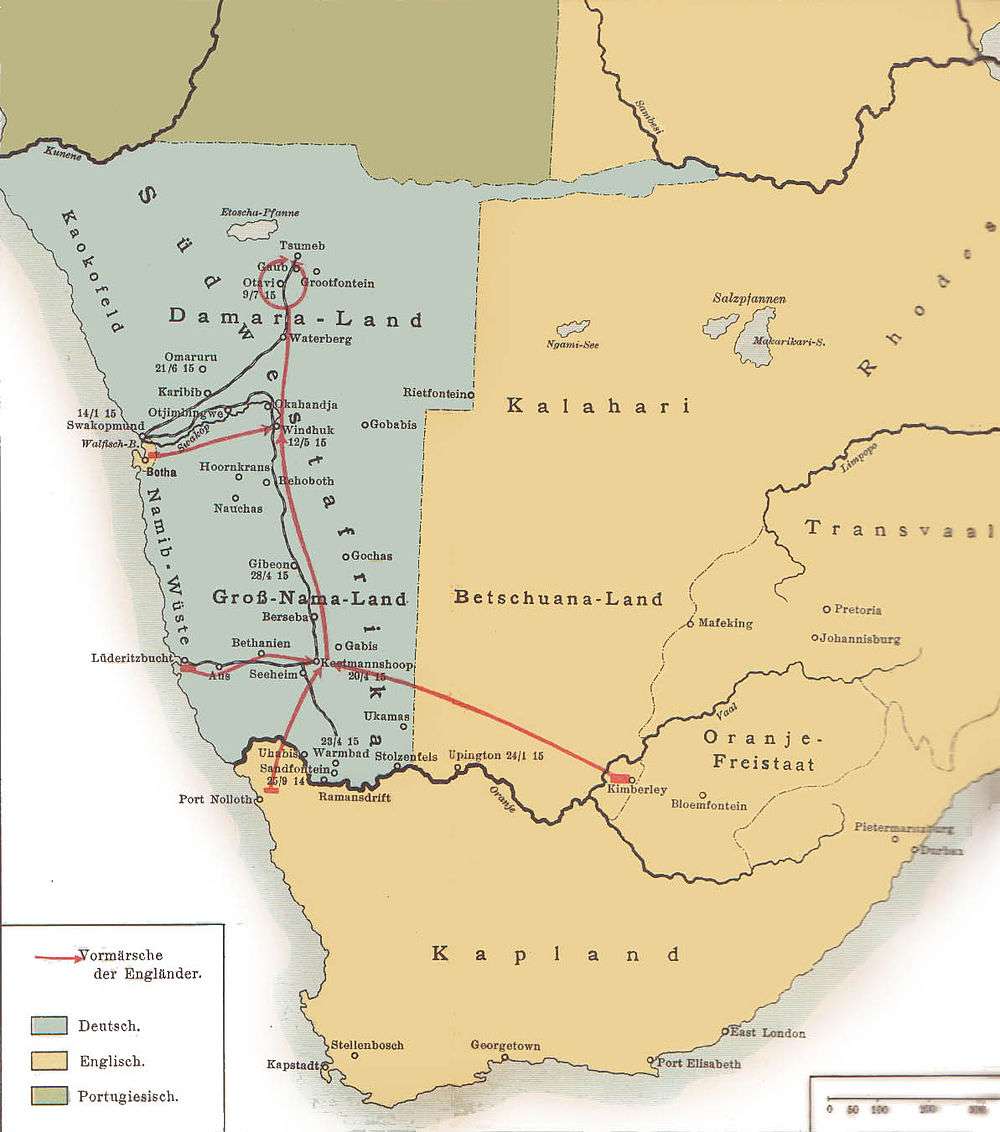

Botha arrived at the coastal German colonial town of Swakopmund, on 11 February to take direct command on the northern contingent, and continued to build up his invasion force at Walfish Bay (or Walvis Bay)—a South African enclave about halfway along the coast of German South West Africa (see the map). By March he was ready to invade. Advancing from Swakopmund along the Swakop valley with its railway line, his forces took Otjimbingwe, Karibib, Friedrichsfelde, Wilhelmsthal and Okahandja and entered the capital Windhuk on 5 May 1915.[7]

The Germans then offered terms under which they would surrender but they were rejected by Botha and the war continued.[6] On 12 May Botha declared martial law and having cut the colony in half, divided his forces into four contingents under Coen Brits, Lukin, Manie Botha and Myburgh. Brits went north to Otjiwarongo, Outjo and Etosha Pan which cut off German forces in the interior from the coastal regions of Kunene and Kaokoveld. The other three columns fanned out into the north-east. Lukin went along the railway line running from Swakopmund to Tsumeb. The other two columns advanced on Lukin's right flank, Myburgh to Otavi junction and Manie Botha to Tsumeb and the line's terminus. The men who commanded these columns, having gained their military experience fighting in Boer commandos, moved very rapidly.[7] The German forces in the north-west made a stand at Otavi on 1 July but were beaten and surrendered at Khorab on 9 July 1915.[8]

While events were unfolding in the north, Smuts landed with another South African force at the South West Africa colony's naval base at Luderitzbucht (now called Angra Pequena). Having secured the town Smuts advanced inland, capturing Keetmanshoop on 20 May. Here he met up with two other columns that had advanced over the border from South Africa, one from the coastal town of Port Nolloth and the other from Kimberley.[9] Smuts advanced north along the railway line to Berseba and after two days fighting captured Gibeon on 26 May.[6][10] The Germans in the south were forced to retreat northwards towards their capital and into the waiting arms of Botha's forces. Within two weeks the German forces in the south, faced with certain destruction, surrendered.[7]

When the Germans provided lists of the names of approximately 2,200 troops under their command, Botha told the German delegation that he had been tricked, as he knew that the Germans had 15,000 men. Victor Franke, the German commander, replied, "If we had 15,000 men then you wouldn't be here and we wouldn't be in this position." [11]

Combat between German and Portuguese forces

Before an official declaration of war between Germany and Portugal (March 1916), German and Portuguese troops clashed several times on the border between German South West Africa and Portuguese Angola. The Germans won most of these clashes and were able to occupy the Humbe region in southern Angola until Portuguese control was restored a few days before the successful South African campaign defeated the Germans.

Aftermath

South African casualties were 113 killed, 153 died of injury or illness and 263 wounded. German casualties were 103 killed, 890 taken prisoner, 37 field guns and 22 machine-guns captured.[12] After defeating the German force in South West Africa, South Africa occupied the colony and then administered it as a League of Nations mandate territory from 1919.

Although the South African government desired to incorporate South West Africa into its territory, it never officially did so, although it was administered as the de facto 'fifth province', with the white minority having representation in the whites-only Parliament of South Africa, as well as electing their own local administration the SWA Legislative Assembly. The South African government also appointed the SWA administrator, who had extensive powers. Following the League's supersession by the United Nations in 1946, South Africa refused to surrender its earlier mandate and the U.N. General Assembly revoked it. In 1971 the International Court of Justice issued an "advisory opinion" declaring South Africa's continued administration to be illegal.[13]

Notes

- Mitchell & Smith 1931, pp. 263–264.

- Portugal e a Grande Guerra 1914-18.

- Bunting 1964, p. 332.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 550, 555.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 550, 552, 554.

- Tucker & Wood 1996, p. 654.

- Crafford 1943, p. 102.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 556–557.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 559–565.

- Burg & Purcell 2004, p. 59.

- Mansfeld 2017, pp. 141-142.

- Strachan 2001, p. 568.

- ACED 2017.

References

- Bunting, B. (1964). The Rise of the South African Reich. London: Penguin. ISBN 0904759741.

- Burg, David F.; Purcell, L. Edward (2004). Almanac of World War I (Illus. ed.). University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-9087-7.

- Crafford, F. S. (1943). Jan Smuts: A Biography (reprint 2005 ed.). Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4179-9290-4.

- Fraga, L. A. (2010). Do intervencionismo ao sidonismo: os dois segmentos da política de guerra na 1a República, 1916–1918 [From Interventionism to Sidonism: The two Segments of the War Policy in the 1st Republic, 1916–1918] (in Portuguese). Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra. ISBN 978-989-26-0034-5.

- Mansfeld, Eugen (2017). The Autobiography of Eugene Mansfeld: A Settler's Life in Colonial Namibia. London: Jeppestown Press. ISBN 978-0-9570837-4-5.

- Mitchell, Thomas John; Smith, G. M. (1931). Casualties and Medical Statistics of the Great War. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence. London: HMSO. OCLC 14739880.

- "Namibian War of Independence 1966–1988". Armed Conflict Events Database. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

- Stejskal, James (2014). The Horns of the Beast: The Swakop River Campaign in South West Africa: 1914–1915. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-19099-827-89.

- Tucker, S.; Wood, L. M. (1996). Tucker, Spencer; Wood, Laura Matysek; Murphy, Justin D. (eds.). The European powers in the First World War: an Encyclopedia (Illus. ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-0399-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waldeck, K. (2010). Gut und Blut für unsern Kaiser. Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99945-71-55-0.

Further reading

- Collyer, J. J. (1922). "South West Africa: Military Operations 1914–1915". Encyclopædia Britannica. 31 (12th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 229–231. OCLC 232333208. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Patterson, H. "First Allied Victory: The South African Campaign in German South West Africa, 1914–1915". Military History Journal. The South African Military History Society. 13 (2). ISSN 0026-4016. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- Walker, H. F. B. (1917). A Doctor's Diary in Damaraland. London: Edward Arnold. OCLC 3586466. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Historicus Africanus (2011), Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15, 1. Band; 2nd edition. Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99916-872-1-6

- Historicus Africanus (2012), Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15, 2. Band, "Naulila", Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99916-872-3-0

- Historicus Africanus (2014), Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15, 3. Band, "Kämpfe im Süden", Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99916-872-8-5

- Historicus Africanus (2016), Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15, 4. Band, "Der Süden ist verloren", Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99916-909-2-6

- Historicus Africanus (2016), Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15, 5. Band, "Aufgabe der Küste", Windhoek: Glanz 6 Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99916-909-4-0

- Historicus Africanus (2017), Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15, 6. Band, Aufgabe der Zentralregionen", Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99916-909-5-7

- Historicus Africanus (2018), Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15, 7. Band, Der Ring schließt sich", Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99916-909-7-1

- Historicus Africanus (2018), Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15, 8. Band, Das Ende bei Khorab", Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99916-909-9-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South West Africa Campaign. |

- The Battle of Sandfontein

- Hypertext version of The Rise of the South African Reich, Brian Bunting, chapter 1. A source for the quote from Manie Maritz.

- Sol Plaatje, Native Life in South Africa: Chapter XXIII — The Boer Rebellion

- 90th anniversary of German defeat in South West Africa from the Great War Society

- Chronology of Events in the Defense of the Portuguese African Colonies, 1914–1920 (in Portuguese)