First Battle of the Masurian Lakes

The First Battle of the Masurian Lakes was a German offensive in the Eastern Front during the early stages of World War I. It pushed the Russian First Army back across its entire front, eventually ejecting it from Germany. Further progress was hampered by the arrival of the Russian Tenth Army on the Germans' right flank.

| First Battle of the Masurian Lakes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War I | |||||||

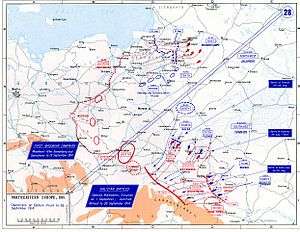

Eastern Front to 26 September 1914. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total 215,000 soldiers:[1] 16 infantry divisions 2 cavalry divisions |

Total 146,000 soldiers 14 infantry divisions 3 cavalry divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,000[2][3]–40,000 killed, wounded and missing[4][5][6] |

100,000[7][8]–125,000 killed, wounded and captured,[9][10][11] 70,000 killed and wounded,[4] 30,000[12]–45,000 prisoners | ||||||

Background

The Russian offensive in East Prussia had started well enough, with General Paul von Rennenkampf's First Army (Army of the Neman) forcing the Eighth Army westward from the border towards Königsberg. Meanwhile, the Russian Second Army invaded from the south, hoping to cut the Germans off in the area around the city but making slow progress against a single German army corps.

However, during their advance Yakov Zhilinsky, Chief of Staff of the Imperial Russian Army, made a strategic mistake by separating two large Russian armies and urging them to move rapidly over a marginally trafficable terrain in response to the requests of the French for an early offensive. As a result, the armies approached in a poorly coordinated manner, being isolated from each other by terrain obstacles, and before the logistical base could be established, the troops were worn down by a rapid march and had to face fresh German troops.[13]

The Germans developed a plan to rapidly move their forces to surround the Second Army as it moved northward over some particularly hilly terrain. The danger was that the First Army would turn to their aid, thereby flanking the German forces. However, the Russians broadcast their daily marching orders "in the clear" on the radio, and the Germans learned that the First Army was continuing to move away from the Second. Using railways in the area, the German forces maneuvered and eventually surrounded and destroyed the Second Army at the Battle of Tannenberg between 26 and 30 August 1914.

As the battle unfolded and the danger to the Second Army became clear, the First Army finally responded by sending units to help. By the time the battle proper ended on 30 August the closest of Rennenkampf's units, his II Corps, was still over 45 miles (70 km) from the pocket. In order to get even this close, his units had to rush southward and were now spread out over a long line running southward from just east of Königsberg. An attack by the German Eighth Army from the west would flank the entire army. Of course, the Germans were also far away, but unlike the Russians, the Germans could easily close the distance using their rail network in the area.

On 31 August, with Tannenberg lost, Zhilinsky ordered Rennenkampf to stand his ground in the event of a German attack. Realizing his forces were too spread out to be effective, he ordered a withdrawal to a line running from Königsberg's defensive works in the north to the Masurian Lakes near Angerburg (Węgorzewo, Poland) in the south, anchored on the Angrapa River. Bolstering his forces were the newly formed XXVI Corp, which he placed in front of Königsberg (a fortress on the Baltic Sea), moving his more experienced troops south into his main line. His forces also included two infantry divisions held in reserve. All in all, he appeared to be in an excellent position to await the arrival of the Russian Tenth Army, forming up to his south.

Battle

German efforts at mopping up the remains of the Second Army were essentially complete by 2 September and Hindenburg immediately started moving his units to meet the southern end of Rennenkampf's line. He was able to safely ignore the Russian right (in the north), which was in front of the extensive defensive works outside of Königsberg. Adding to his force were two newly arrived Corps from the Western Front, the Guards Reserve Corps and the XI Corps. Then, like Rennenkampf, Hindenburg fed his newest troops into the northern end of the line and planned an offensive against the south. But unlike Rennenkampf, Hindenburg had enough forces not only to cover the entire front in the Insterburg Gap but had additional forces left over. He sent his most capable units, the I Corps and XVII Corps, far to the south of the lines near the middle of the Lakes, and sent the 3rd Reserve Division even further south to Lyck, about 30 miles from the southern end of Rennenkampf's line.

Hindenburg's southern divisions began their attack on 7 September, with the battle proper opening the next day. Throughout 8 September the German forces in the north hammered at the Russian forces facing them, forcing an orderly retreat eastward. In the south, however, things were going much worse. The German XVII Corps had met their counterpart, the Russian II Corps, but were at this point outnumbered. The Russian II Corps maneuvered well, and by the end of the day had gotten their left flank into position for a flanking attack on the Germans, potentially encircling them.

However, all hope of a Russian victory vanished the following day when then the German I Corps arrived in support of the XVII; now the Russians were outflanked. Meanwhile, the 3rd Reserve Division had engaged the Russians' XXII Corps even further south, and after a fierce battle forced them to fall back southeastward; its commander wired Rennenkampf he had been attacked and defeated near Lyck, and could do nothing but withdraw. Rennenkampf ordered a counteroffensive in the north to buy time to reform his lines, managing to push the German XX Corps back a number of miles. However, the Germans did not stop to reform their lines but instead continued their advances in the south and north. This left the victorious Russian troops isolated but still able to retreat to new lines being set up in the east.

Now the battle turned decisively in the Germans' favor. By 11 September the Russians had been pushed back to a line running from Insterburg to Angerburg in the north, with a huge flanking maneuver developing to the south. It was at this point that the threat of encirclement appeared possible. Rennenkampf ordered a general retreat toward the Russian border, which happened rapidly under the protection of a strong rear guard. It was this speed that enabled the retreating Russian troops to escape the trap Hindenburg had planned for them. The German commander had ordered his wings to quicken their march as much as possible, but a trivial accident—a rumor of a Russian counterattack—cost the Germans half a day's march, allowing the Russians to escape to the east. These reached Gumbinnen the next day, and Stallupönen on the 13th. The remains of the First Army retreated to the safety of their own border forts. Likewise, the Tenth Army was forced back into Russia. German casualties were about 40,000, Russian 100,000.[8]

Outcome

This was a strategically significant victory for The Eighth Army, completely destroying the Second Army, mauling the First, and pushing back all Russian troops in that region beyond the pre-war borders. Meanwhile, new German corps (under von der Goltz) were able to use this movement to safely move into position to harass the scattered remains of the Second Army, while far to the southwest the new German Ninth was forming up. It would not be long before they were able to face the Russians in a position of numerical superiority.

However, this advantage was bought at a cost: the newly arrived corps had been sent from the Western front and their absence would be felt in the upcoming Battle of the Marne. Much of the territory taken by the Germans would later be lost to a Russian counterattack during 25–28 September.[4]

Around the same time far south on the Eastern Front, Russian forces routed the Austro-Hungarian army. It took another year before the German and Austro-Hungarian forces were finally able to reverse the Russian advances, pushing them out of Galicia and then Russian Poland.

See also

References

- Hans Niemann, Hindenburgs Siegeszug gegen Rußland, Berlin : Mittler & Sohn, 1917, p. 44.

- David Eggenberger, An Encyclopedia of Battles: Accounts of Over 1,560 Battles, 2012, p. 270

- Dennis Cove,Ian Westwell, History of World War I, 2002, p. 157

- Spencer C. Tucker. World War I: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. 2014. P. 1048

- Timothy C. Dowling. Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. 2014. P. 509

- Prit Buttar. Collision of Empires: The War on the Eastern Front in 1914. Osprey Publishing. 2014. P. 239

- Tucker S. The Great War, 1914-1918. Routledge. 2002. P. 44

- Gray, Randall; Argyle, Christopher (1990–91). Chronicle of the First World War. New York: Oxford. p. vol. I, 282.

- David Eggenberger, (2012), p. 270

- Christine Hatt, The First World War, 1914-18, 2007, p. 15

- Roger Chickering, Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914-1918, 2004, p. 26

- F. Kagan, R. Higham. The Military History of Tsarist Russia. Springer, 2016. P. 230

- William R. Griffiths. The Great War. Square One Publishers, 2003. P. 48