Armenian Genocide

The Armenian Genocide[lower-alpha 3] (also sometimes known as the Armenian Holocaust)[13] was the systematic mass murder and expulsion of 1.5 million[lower-alpha 2] ethnic Armenians carried out in Turkey and adjoining regions by the Ottoman government between 1914 and 1923.[14][15] The starting date is conventionally held to be 24 April 1915, the day that Ottoman authorities rounded up, arrested, and deported from Constantinople (now Istanbul) to the region of Angora (Ankara), 235 to 270 Armenian intellectuals and community leaders, the majority of whom were eventually murdered.

| Armenian Genocide | |

|---|---|

| Part of the late Ottoman genocides[1][2] | |

| |

| Location |

|

| Date | 1914–1923[lower-alpha 1] |

| Target | Armenian population |

Attack type | Deportation, genocide, mass murder, starvation |

| Deaths | c. 1.5 million (disputed)[lower-alpha 2] |

| Perpetrators | Ottoman Empire (Committee of Union and Progress) |

| Motive | Anti-Armenian sentiment,[10] Turkification, Islamization[11] |

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

| Issues |

| Genocide of indigenous peoples |

|

| Late Ottoman genocides |

| World War II (1941–1945) |

| Cold War |

|

| Genocides in postcolonial Africa |

|

| Ethno-religious genocide in contemporary era |

|

| Related topics |

| Category |

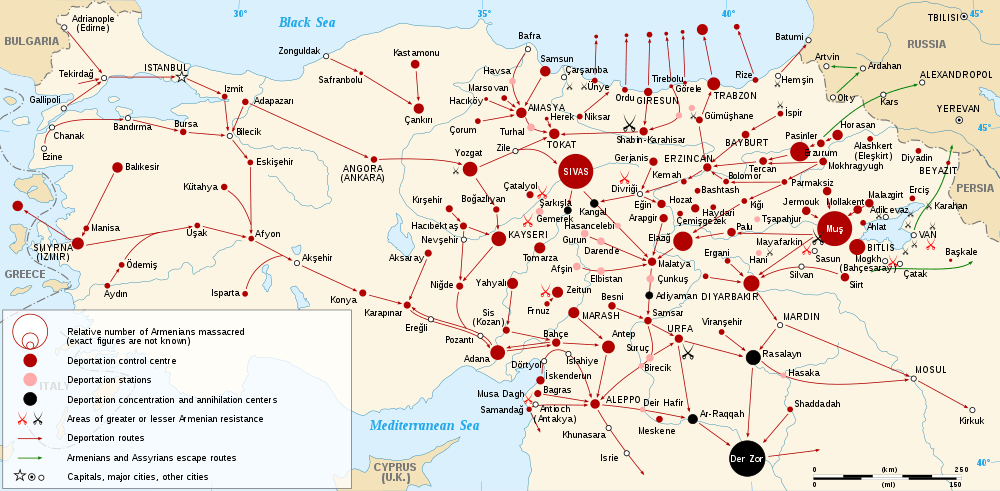

The genocide was carried out during and after World War I and implemented in two phases—the wholesale killing of the able-bodied male population through massacre and subjection of army conscripts to forced labour, followed by the deportation of women, children, the elderly, and the infirm on death marches leading to the Syrian Desert. Driven forward by military escorts, the deportees were deprived of food and water and subjected to periodic robbery, rape, and massacre.[16] Most Armenian diaspora communities around the world came into being as a direct result of the genocide.[17]

Other ethnic groups were similarly targeted for extermination in the Assyrian genocide and the Greek genocide, and their treatment is considered by some historians to be part of the same genocidal policy.[1][2]

Raphael Lemkin was moved specifically by the annihilation of the Armenians to define systematic and premeditated exterminations within legal parameters and to coin the word genocide in 1943.[18] The Armenian Genocide is acknowledged to have been one of the first modern genocides,[19][20][21] because scholars point to the organized manner in which the killings were carried out. It is the second-most-studied case of genocide after the Holocaust.[22]

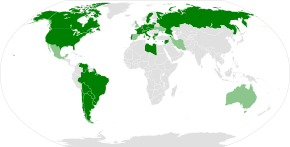

Turkey denies that the word genocide is an accurate term for these crimes, but in recent years has been faced with increasing calls to recognize them as such.[23] As of 2019, governments and parliaments of 32 countries, including the United States, Russia, and Germany, have recognized the events as a genocide.

Terminology

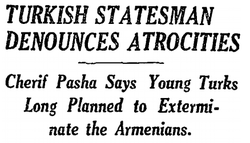

The Armenian Genocide took place before the coining of the term genocide. English-language words and phrases used by contemporary accounts to characterise the event include "massacres", "atrocities", "annihilation", "holocaust", "the murder of a nation", "race extermination" and "a crime against humanity".[24] Raphael Lemkin coined "genocide" in 1943, with the fate of the Armenians in mind; he later explained that: "it happened so many times ... It happened to the Armenians, then after the Armenians Hitler took action."[25]

The survivors of the genocide used a number of Armenian terms to name the event. Mouradian writes that Yeghern (Crime/Catastrophe), or variants like Medz Yeghern (Great Crime) and Abrilian Yeghern (the April Crime) were the terms most commonly used.[26] The name Aghed, usually translated as "Catastrophe", was, according to Beledian, the term most often used in Armenian literature to name the event.[27][28] After the coining of the term genocide, the portmanteau word Armenocide was also used as a name for the Armenian Genocide.[29]

Works that seek to deny the Armenian Genocide often attach qualifying words against the term genocide, such as "so-called", "alleged", or "disputed", or characterise it as a "controversy", or dismiss it as "Armenian allegations", "Armenian claims",[30] or "Armenian lies", or employ euphemisms to avoid the word genocide, such as calling it a "tragedy for both sides", or "the events of 1915".[31] American President Barack Obama's use of the term Medz Yeghern when referring to the Armenian Genocide has been described "as a means of avoiding the word genocide".[32]

Several international organizations have conducted studies of the atrocities, each in turn determining that the term "genocide" aptly describes "the Ottoman massacre of Armenians in 1915–16".[33] Among the organizations affirming this conclusion are the International Center for Transitional Justice,[33] the International Association of Genocide Scholars,[34] and the United Nations' Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities.[35]

In 2005, the International Association of Genocide Scholars affirmed that scholarly evidence revealed the "Young Turk government of the Ottoman Empire began a systematic genocide of its Armenian citizens – an unarmed Christian minority population. More than a million Armenians were exterminated through direct killing, starvation, torture, and forced death marches."[36] The IAGS also condemned Turkish attempts to deny the factual and moral reality of the Armenian Genocide. In 2007, the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity produced a letter[37] signed by 53 Nobel laureates re-affirming the Genocide Scholars' conclusion that the 1915 killings of Armenians constituted genocide.[38][39]

Bat Ye'or has suggested that "the genocide of the Armenians was a jihad".[40] This perspective is challenged by Faiz el-Ghusein, a Bedouin Arab witness of the Armenian persecution, whose 1918 treatise aimed "to refute beforehand inventions and slanders against the Faith of Islam and against Moslems generally ... [W]hat the Armenians have suffered is to be attributed to the Committee of Union and Progress ... [I]t has been due to their nationalist fanaticism and their jealousy of the Armenians, and to these alone; the Faith of Islam is guiltless of their deeds".[41]:49 Arnold J. Toynbee writes that "the Young Turks made Pan-Islamism and Turkish Nationalism work together for their ends, but the development of their policy shows the Islamic element receding and the Nationalist gaining ground".[42] Toynbee and various other sources report that many Armenians were spared death by marrying into Turkish families or converting to Islam. Concerned that Westerners would come to regard the "extermination of the Armenians" as "a black stain on the history of Islam, which the ages will not efface", El-Ghusein also observes that many Armenian converts were put to death.[41]:39 In one instance, when an Islamic leader appealed to spare Armenian converts to Islam, El-Ghusein quotes a government official as responding that "politics have no religion", before sending the converts to their deaths.[41]:49

Background

Armenians under Ottoman rule

The western portion of historical Armenia, known as Western Armenia, had come under Ottoman jurisdiction by the Peace of Amasya (1555) and was permanently divided from Eastern Armenia by the Treaty of Zuhab (1639).[43][44] Thereafter, the region was alternatively referred to as "Turkish" or "Ottoman" Armenia.[45] The vast majority of Armenians were grouped together into a semi-autonomous community, the Armenian millet, which was led by one of the spiritual heads of the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople. Armenians were mainly concentrated in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire, although large communities were also found in the western provinces, as well as in the capital, Constantinople.

The Armenian community was made up of three religious denominations: Armenian Catholic, Armenian Protestant, and Armenian Apostolic, the Church of the vast majority of Armenians. Under the millet system, the Armenian community was allowed to rule itself under its own system of governance with fairly little interference from the Ottoman government. Most Armenians—approximately 70%—lived in poor and dangerous conditions in the rural countryside, with the exception of the wealthy, Constantinople-based Amira class, a social elite whose members included the Duzians (Directors of the Imperial Mint), the Balyans (Chief Imperial Architects) and the Dadians (Superintendent of the Gunpowder Mills and manager of industrial factories).[46][47] Ottoman census figures clash with the statistics collected by the Armenian Patriarchate, but according to the latter, there were almost three million Armenians living in the empire in 1878 (400,000 in Constantinople and the Balkans, 600,000 in Asia Minor and Cilicia, 670,000 in Lesser Armenia and the area near Kayseri, and 1,300,000 in Western Armenia).[48]

In the eastern provinces, the Armenians were subject to the whims of their Turkish and Kurdish neighbors, who would regularly overtax them, subject them to brigandage and kidnapping, force them to convert to Islam, and otherwise exploit them without interference from central or local authorities.[47] In the Ottoman Empire, in accordance with the dhimmi system implemented in Muslim countries, they, like all other Christians and also Jews, were accorded certain freedoms. The dhimmi system in the Ottoman Empire was largely based upon the Pact of Umar. The client status established the rights of the non-Muslims to property, livelihood and freedom of worship, but they were in essence treated as second-class citizens in the empire and referred to in Turkish as gavours, a pejorative word meaning "infidel" or "unbeliever". The clause of the Pact of Umar which prohibited non-Muslims from building new places of worship was historically imposed on some communities of the Ottoman Empire and ignored in other cases, at the discretion of local authorities. Although there were no laws mandating religious ghettos, this led to non-Muslim communities being clustered around existing houses of worship.[49][50]

In addition to other legal limitations, Christians were not considered equals to Muslims and several prohibitions were placed on them. Testimony against Muslims by Christians and Jews was inadmissible in courts of law wherein a Muslim could be punished; this meant that their testimony could only be considered in commercial cases. They were forbidden to carry weapons or ride atop horses and camels. Their houses could not overlook those of Muslims; and their religious practices were severely circumscribed, e.g., the ringing of church bells was strictly forbidden.[49][51]

Reform, 1840s–1880s

In the mid-19th century, the three major European powers—the United Kingdom, France and Russia—began to question the Ottoman Empire's treatment of its Christian minorities and pressure it to grant equal rights to all its subjects. From 1839 to the declaration of a constitution in 1876, the Ottoman government instituted the Tanzimat, a series of reforms designed to improve the status of minorities. Nevertheless, most of the reforms were never implemented because the empire's Muslim population rejected the principle of equality for Christians. By the late 1870s, the European Greeks, along with several other Christian nations in the Balkans, frustrated with their conditions, had, often with the help of the Entente powers, broken free of Ottoman rule.[52]:192[53]

The Armenians remained, by and large, passive during these years, earning them the title of millet-i sadika or the "loyal millet".[54] In the mid-1860s and early 1870s this passivity gave way to new currents of thinking in Armenian society. Led by intellectuals educated at European universities or American missionary schools in Turkey, Armenians began to question their second-class status and press for better treatment from their government. In one such instance, after amassing the signatures of peasants from Western Armenia, the Armenian Communal Council petitioned the Ottoman government to redress their principal grievances: "the looting and murder in Armenian towns by [Muslim] Kurds and Circassians, improprieties during tax collection, criminal behavior by government officials and the refusal to accept Christians as witnesses in trial". The Ottoman government considered these grievances and promised to punish those responsible, but no meaningful steps to do so were ever taken.[51]:36

Following the violent suppression of Christians during the Great Eastern Crisis, particularly in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria and Serbia, the United Kingdom and France invoked the 1856 Treaty of Paris by claiming that it gave them the right to intervene and protect the Ottoman Empire's Christian minorities.[51]:35ff Under growing pressure, the government of Sultan Abdul Hamid II declared itself a constitutional monarchy with a parliament (which was almost immediately prorogued) and entered into negotiations with the powers. At the same time, the Armenian patriarch of Constantinople, Nerses II, forwarded Armenian complaints of widespread "forced land seizure ... forced conversion of women and children, arson, protection extortion, rape, and murder" to the Powers.[51]:37

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 ended with Russia's decisive victory and its army in occupation of large parts of eastern Turkey, but not before entire Armenian districts had been devastated by massacres carried out with the connivance of Ottoman authorities. In the wake of these events, Patriarch Nerses and his emissaries made repeated approaches to Russian leaders to urge the inclusion of a clause granting local self-government to the Armenians in the forthcoming Treaty of San Stefano, which was signed on 3 March 1878. The Russians were receptive and drew up the clause, but the Ottomans flatly rejected it during negotiations. In its place, the two sides agreed on a clause making the Sublime Porte's implementation of reforms in the Armenian provinces a condition of Russia's withdrawal, thus designating Russia the guarantor of the reforms.[55] The clause entered the treaty as Article 16 and marked the first appearance of what came to be known in European diplomacy as the Armenian Question.

On receiving a copy of the treaty, Britain promptly objected to it and particularly Article 16, which it saw as ceding too much influence to Russia. It immediately pushed for a congress of the great powers to be convened to discuss and revise the treaty, leading to the Congress of Berlin in June–July 1878.[lower-alpha 4] Patriarch Nerses of the Armenian Apostolic Church sent a delegation led by his distinguished predecessor, Archbishop Khrimian Hayrik, to speak for the Armenians, but it was not admitted into the sessions on the grounds that it did not represent a country. Confined to the periphery, the delegation did its best to contact the representatives of the powers and argue the case for Armenian administrative autonomy within the Ottoman Empire, but to little effect.

Following an understanding reached with Ottoman representatives, Britain drew up an emasculated version of Article 16 to replace the original, a clause that retained the call for reforms, but omitted any reference to the Russian occupation, thereby dispensing with the principal guarantee of their implementation. Despite an ambiguous reference to Great Power supervision, the clause failed to offset the removal of the Russian guarantee with any tangible equivalent, thus leaving the timing and fate of the reforms to the discretion of the Sublime Porte.[51]:38–39 The clause was readily adopted as Article 61 of the Treaty of Berlin on the last day of the Congress, 13 July 1878, to the deep disappointment of the Armenian delegation.

Armenian national liberation movement

Prospects for reforms faded rapidly following the signing of the Berlin treaty, as security conditions in the Armenian provinces went from bad to worse and abuses proliferated. Upset with this turn of events, a number of disillusioned Armenian intellectuals living in Europe and Russia decided to form political parties and societies dedicated to the betterment of their compatriots in the Ottoman Empire. In the last quarter of the 19th century, this movement came to be dominated by three parties: the Armenakan, whose influence was limited to Van; the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party; and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutiun). Ideological differences aside, all the parties had the common goal of achieving better social conditions for the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire through self-defense[57][58] and advocating increased European pressure on the Ottoman government to implement the promised reforms.

Hamidian massacres, 1894–1896

Soon after the Treaty of Berlin was signed, Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876–1909) attempted to forestall the implementation of its reform provisions by asserting that Armenians did not make up a majority in the provinces and that their reports of abuses were largely exaggerated or false. In 1890, Abdul Hamid created a paramilitary outfit known as the Hamidiye, which was mostly made up of Kurdish irregulars tasked to "deal with the Armenians as they wished".[50]:40 As Ottoman officials intentionally provoked rebellions (often as a result of over-taxation) in Armenian populated towns, such as in Sasun in 1894 and Zeitun in 1895–1896, those regiments were increasingly used to deal with the Armenians by way of oppression and massacre. In some instances, Armenians successfully fought off the regiments and in 1895 brought the excesses to the attention of the Great Powers, who subsequently condemned the Porte.[51]:40–42

In May 1895, the Powers forced Abdul Hamid to sign a new reform package designed to curtail the powers of the Hamidiye, but, like the Berlin Treaty, it was never implemented. On 1 October 1895, 2,000 Armenians assembled in Constantinople to petition for the implementation of the reforms, but Ottoman police units violently broke the rally up.[50]:57–58 Soon, massacres of Armenians broke out in Constantinople and then engulfed the rest of the Armenian-populated provinces of Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Erzurum, Harput, Sivas, Trebizond (Trabzon), and Van. Estimates differ on how many Armenians were killed, but European documentation of the pogroms, which became known as the Hamidian massacres, placed the figures at between 100,000 and 300,000.[60]

Although Hamid was never directly implicated, it is believed that the massacres had his tacit approval.[51]:42 Frustrated with European indifference to the massacres, a group of members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation seized the European-managed Ottoman Bank on 26 August 1896. This incident brought further sympathy for Armenians in Europe and was lauded by the European and American press, which vilified Hamid and painted him as the "great assassin", "bloody Sultan", and "Abdul the Damned".[50]:35, 115 The Great Powers vowed to take action and enforce new reforms, which never came to fruition due to conflicting political and economic interests.

Prelude to the genocide

Young Turk Revolution of 1908

On 24 July 1908, Armenians' hopes for equality in the Ottoman Empire brightened when a coup d'état staged by officers in the Ottoman Third Army based in Salonika removed Abdul Hamid II from power and restored the country to a constitutional monarchy. The officers were part of the Young Turk movement that wanted to reform administration of the perceived decadent state of the Ottoman Empire and modernize it to European standards.[61] The movement was an anti-Hamidian coalition made up of two distinct groups, the liberal constitutionalists and the nationalists. The former were more democratic and accepting of Armenians, whereas the latter were less tolerant of Armenians and their frequent requests for European assistance.[50]:140–41 In 1902, during a congress of the Young Turks held in Paris, the heads of the liberal wing, Sabahaddin and Ahmed Riza Bey, partially persuaded the nationalists to include in their objectives ensuring some rights for all the minorities of the empire.

One of the numerous factions within the Young Turk movement was a secret revolutionary organization called the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). It drew its membership from disaffected army officers based in Salonika and was behind a wave of mutinies against the central government. In 1908, elements of the Third Army and the Second Army Corps declared their opposition to the Sultan and threatened to march on the capital to depose him. Hamid, shaken by the wave of resentment, stepped down from power as Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians, Arabs, Bulgarians and Turks alike rejoiced in his dethronement.[50]:143–44

Adana massacre of 1909

A countercoup took place in early 1909, ultimately resulting in the 31 March Incident on 13 April 1909. Some reactionary Ottoman military elements, joined by Islamic theological students, aimed to return control of the country to the Sultan and the rule of Islamic law. Riots and fighting broke out between the reactionary forces and CUP forces, until the CUP was able to put down the uprising and court-martial the opposition leaders.

While the movement initially targeted the Young Turk government, it spilled over into pogroms against Armenians who were perceived as having supported the restoration of the constitution.[51]:68–69 About 4,000 Turkish civilians and soldiers participated in the rampage.[62] Estimates of the number of Armenians killed in the course of the Adana massacre range between 15,000 and 30,000 people.[51]:69[63]

Conflict in the Balkans and Russia

In 1912, the First Balkan War broke out and ended with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire as well as the loss of 85% of its European territory. Many in the empire saw their defeat as "Allah's divine punishment for a society that did not know how to pull itself together".[51]:84 The Turkish nationalist movement in the country gradually came to view Anatolia as their last refuge. The Armenian population formed a significant minority in this region.

An important consequence of the Balkan Wars was also the mass expulsion of Muslims (known as muhacirs) from the Balkans. Beginning in the mid-19th century, hundreds of thousands of Muslims, including Turks, Circassians, and Chechens, were forcibly expelled and others voluntarily migrated from the Caucasus and the Balkans (Rumelia) as a result of the Russo-Turkish wars, the Circassian genocide and the conflicts in the Balkans. Muslim society in the empire was incensed by this flood of refugees. A journal published in Constantinople expressed the mood of the times: "Let this be a warning ... O Muslims, don't get comfortable! Do not let your blood cool before taking revenge".[51]:86 As many as 850,000 of these refugees were settled in areas where the Armenians resided. The muhacirs resented the status of their relatively well-off neighbors and, as historian Taner Akçam and others have noted, some of them came to play a pivotal role in the killings of the Armenians and the confiscation of their properties during the genocide.[51]:86–87

Incitement

Ottoman propaganda described Armenians as "traitors, saboteurs, spies, conspirators, vermin, and infidels". At a meeting of the Committee of Union and Progress in February 1915, a speaker argued that "It is absolutely necessary to eliminate the Armenian people in its entirety, so that there is no further Armenian on this earth and the very concept of Armenia is extinguished." The party "envisioned the Armenian as an invasive infection in Muslim Turkish society", and CUP propagandist Ziya Gökalp promoted the idea that "Turkey could only be revitalized if it rid itself of its non-Muslim elements".[64] This incitement to genocide led directly to the murder of over a million Armenians.[65]

World War I

On 2 November 1914, the Ottoman Empire opened the Middle Eastern theater of World War I by entering hostilities on the side of the Central Powers and against the Allies. The battles of the Caucasus Campaign, the Persian Campaign and the Gallipoli Campaign affected several populous Armenian centers. Before entering the war, the Ottoman government had sent representatives to the Armenian congress at Erzurum to persuade Ottoman Armenians to facilitate its conquest of Transcaucasia by inciting an insurrection of Russian Armenians against the Russian army in the event a Caucasus front was opened.[51]:136[66] On 24 December 1914, Minister of War Enver Pasha implemented a plan to encircle and destroy the Russian Caucasus Army at Sarikamish in order to regain territories lost to Russia after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. Enver Pasha's forces were routed in the battle, and almost completely destroyed. Returning to Constantinople, Enver Pasha publicly blamed his defeat on Armenians in the region having actively sided with the Russians.[50]:200 In November 1914 Shaykh ul-Islam proclaimed Jihad (Holy War) against the Christians: this was later used as a factor to provoke radical masses in the implementation of the Armenian Genocide.[67]

Labour battalions

On 25 February 1915, the Ottoman General Staff released the War Minister Enver Pasha's Directive 8682 on "Increased security and precautions" to all military units calling for the removal of all ethnic Armenians serving in the Ottoman forces from their posts and for their demobilization. They were assigned to the unarmed Labour battalions (Turkish: amele taburları). The directive accused the Armenian Patriarchate of releasing State secrets to the Russians. Enver Pasha explained this decision as "out of fear that they would collaborate with the Russians".[68] Traditionally, the Ottoman Army only drafted non-Muslim males between the ages of 20 and 45 into the regular army. The younger (15–20) and older (45–60) non-Muslim soldiers had always been used as logistical support through the labour battalions. Before February, some of the Armenian recruits were utilized as labourers (hamals), though they would ultimately be executed.[69] Transferring Armenian conscripts from active combat to passive, unarmed logistic sections was an important precursor to the subsequent genocide. As reported in The Memoirs of Naim Bey, the execution of the Armenians in these battalions was part of a premeditated strategy of the CUP. Many of these Armenian recruits were executed by local Turkish gangs.[50]:178

Van, April 1915

On 19 April 1915, Jevdet Bey demanded that the city of Van immediately furnish him 4,000 soldiers under the pretext of conscription. However, it was clear to the Armenian population that his goal was to massacre the able-bodied men of Van so that there would be no defenders. Jevdet Bey had already used his official writ in nearby villages, ostensibly to search for arms, but in fact to initiate wholesale massacres.[50]:202 The Armenians offered five hundred soldiers and exemption money for the rest in order to buy time, but Jevdet Bey accused the Armenians of "rebellion" and asserted his determination to "crush" it at any cost. "If the rebels fire a single shot", he declared, "I shall kill every Christian man, woman, and" (pointing to his knee) "every child, up to here".[70]:205

The next day, 20 April 1915, the siege of Van began when an Armenian woman was harassed, and the two Armenian men who came to her aid were killed by Ottoman soldiers. The Armenian defenders protected the 30,000 residents and 15,000 refugees living in an area of roughly one square kilometer of the Armenian Quarter and suburb of Aigestan with 1,500 ablebodied riflemen who were supplied with 300 rifles and 1,000 pistols and antique weapons. The conflict lasted until General Yudenich of Russia came to their rescue.[71]

Reports of the conflict reached then United States Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Henry Morgenthau, Sr. from Aleppo and Van, prompting him to raise the issue in person with Talaat and Enver. As he quoted to them the testimonies of his consulate officials, they justified the deportations as necessary to the conduct of the war, suggesting that complicity of the Armenians of Van with the Russian forces that had taken the city justified the persecution of all ethnic Armenians.[70]:300

Arrest and deportation of Armenian notables, April 1915

By 1914, Ottoman authorities had already begun a propaganda drive to present Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire as a threat to the empire's security. An Ottoman naval officer in the War Office described the planning:

In order to justify this enormous crime the requisite propaganda material was thoroughly prepared in Istanbul. [It included such statements as] 'the Armenians are in league with the enemy. They will launch an uprising in Istanbul, kill off the Ittihadist leaders and will succeed in opening up the straits [of the Dardanelles]'.[52]:220

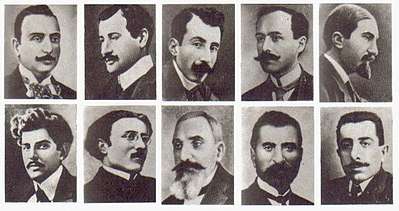

On the night of 23–24 April 1915, known as Red Sunday (Armenian: Կարմիր Կիրակի Garmir Giragi), the Ottoman government rounded up and imprisoned an estimated 250 Armenian intellectuals and community leaders of the Ottoman capital, Constantinople, and later those in other centers, who were moved to two holding centers near Angora (Ankara).[50]:211–12 This date coincided with Allied troop landings at Gallipoli after unsuccessful Allied naval attempts to break through the Dardanelles to Constantinople in February and March 1915.

Following the passage of Tehcir Law on 29 May 1915, the Armenian leaders, except for the few who were able to return to Constantinople, were gradually deported and assassinated.[72][73][74][75][76] The date 24 April is commemorated as Genocide Remembrance Day by Armenians around the world.

Deportations

In May 1915, Mehmet Talaat Pasha requested that the cabinet and Grand Vizier Said Halim Pasha legalize a measure for the deportation of Armenians to other places due to what Talaat Pasha called "the Armenian riots and massacres, which had arisen in a number of places in the country". However, Talaat Pasha was referring specifically to events in Van and extending the implementation to the regions in which alleged "riots and massacres" would affect the security of the war zone of the Caucasus Campaign. Later, the scope of the deportation was widened in order to include the Armenians in the other provinces.[78]

On 29 May 1915, the CUP Central Committee passed the Temporary Law of Deportation ("Tehcir Law"), giving the Ottoman government and military authorization to deport anyone it "sensed" as a threat to national security.[50]:186–88

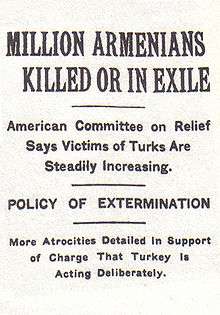

With the implementation of the Tehcir Law, the confiscation of Armenian property and the slaughter of Armenians that ensued upon its enactment outraged much of the Western world. While the Ottoman Empire's wartime allies offered little protest, a wealth of German and Austrian historical documents has since come to attest to the witnesses' horror at the killings and mass starvation of Armenians.[80]:329–31[81]:212–13 In the United States, The New York Times reported almost daily on the mass murder of the Armenian people, describing the process as "systematic", "authorized" and "organized by the government". Theodore Roosevelt would later characterize this as "the greatest crime of the war".[82]

Historian Hans-Lukas Kieser states that, from the statements of Talaat Pasha[83] it is clear that the officials were aware that the deportation order was genocidal.[84] Another historian Taner Akçam states that the telegrams show that the overall coordination of the genocide was taken over by Talaat Pasha.[85] In 2017, Akçam was able to access one of the original telegrams, archived in Jerusalem, which inquired about Armenian liquidation and elimination.[86]

Death marches

The Armenians were marched out to the Syrian town of Deir ez-Zor and the surrounding desert. The Ottoman government deliberately withheld the facilities and supplies that would have been necessary to sustain the life of hundreds of thousands of Armenian deportees during and after their forced march to the Syrian desert.[88][89][90] By August 1915, The New York Times repeated an unattributed report that "the roads and the Euphrates are strewn with corpses of exiles, and those who survive are doomed to certain death. It is a plan to exterminate the whole Armenian people".[91] Talaat Pasha and Djemal Pasha were completely aware that by abandoning the Armenian deportees in the desert they were condemning them to certain death.[92] A dispatch from a "high diplomatic source in Turkey, not American, reporting the testimony of trustworthy witnesses" about the plight of Armenian deportees in northern Arabia and the Lower Euphrates valley was extensively quoted by The New York Times in August 1916:

The witnesses have seen thousands of deported Armenians under tents in the open, in caravans on the march, descending the river in boats and in all phases of their miserable life. Only in a few places does the Government issue any rations, and those are quite insufficient. The people, therefore, themselves are forced to satisfy their hunger with food begged in that scanty land or found in the parched fields. Naturally, the death rate from starvation and sickness is very high and is increased by the brutal treatment of the authorities, whose bearing toward the exiles as they are being driven back and forth over the desert is not unlike that of slave drivers. With few exceptions no shelter of any kind is provided and the people coming from a cold climate are left under the scorching desert sun without food and water. Temporary relief can only be obtained by the few able to pay officials.[88]

Similarly, Major General Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein noted in 1918 while stationed in the Caucasus that "The Turkish policy of causing starvation is an all too obvious proof, if proof was still needed as to who is responsible for the massacre, for the Turkish resolve to destroy the Armenians".[52]:350

German engineers and labourers involved in building the railway also witnessed Armenians being crammed into cattle cars and shipped along the railroad line. Franz Gunther, a representative for Deutsche Bank which was funding the construction of the Baghdad Railway, forwarded photographs to his directors and expressed his frustration at having to remain silent amid such "bestial cruelty".[50]:326 Major General Otto von Lossow, acting military attaché and head of the German Military Plenipotentiary in the Ottoman Empire, spoke to Ottoman intentions in a conference held in Batum in 1918:

The Turks have embarked upon the "total extermination of the Armenians in Transcaucasia ... The aim of Turkish policy is, as I have reiterated, the taking of possession of Armenian districts and the extermination of the Armenians. Talaat's government wants to destroy all Armenians, not just in Turkey, but also outside Turkey. On the basis of all the reports and news coming to me here in Tiflis there hardly can be any doubt that the Turks systematically are aiming at the extermination of the few hundred thousand Armenians whom they left alive until now.[52]:349

Rape was an integral part of the genocide;[93] military commanders told their men to "do to [the women] whatever you wish", resulting in widespread sexual abuse. Deportees were displayed naked in Damascus and sold as sex slaves in some areas, including Mosul according to the report of the German consul there, constituting an important source of income for accompanying soldiers.[94] Dr. Walter Rössler, the German consul in Aleppo during the genocide, heard from an "objective" Armenian that around a quarter of young women, whose appearance was "more or less pleasing", were regularly raped by the gendarmes, and that "even more beautiful ones" were violated by 10–15 men. This resulted in girls and women being left behind dying.[95]

Concentration camps

A network of 25 concentration camps was set up by the Ottoman government to dispose of the Armenians who had survived the deportations to their ultimate point.[96] This network, situated in the region of Turkey's present-day borders with Iraq and Syria, was directed by Şükrü Kaya, one of Talaat Pasha's right-hand men. Some of the camps were only temporary transit points. Others, such as Radjo, Katma, and Azaz, were briefly used as mass graves and then vacated by autumn 1915. Camps such as Lale, Tefridje, Dipsi, Del-El, and Ra's al-'Ayn were built specifically for those whose life expectancy was just a few days.[97] According to genocide scholar Hilmar Kaiser, the Ottoman authorities refused to provide food and water to the victims, increasing the mortality rate. According to The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies, "Muslims were eager to obtain Armenian women. Authorities registered such marriages but did not record the deaths of the former Armenian husbands."[98]

Bernau, an American citizen of German descent, traveled to the areas where Armenians were incarcerated and wrote a report that was deemed factual by Rössler, the German Consul at Aleppo. He reports mass graves containing over 60,000 people in Meskene and large numbers of mounds of corpses, as the Armenians died due to hunger and disease. He reported seeing 450 orphans, who received at most 150 grams (5.3 oz) of bread per day, in a tent of 5 square metres (54 sq ft) to 6 square metres (65 sq ft). Dysentery swept through the camp and days passed between the instances of distribution of bread to some. In "Abu Herrera", near Meskene, he described how the guards let 240 Armenians starve, and wrote that they searched "horse droppings" for grains.[99]

"Special Organization"

The Committee of Union and Progress founded the "Special Organization" (Turkish: Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa) that participated in the destruction of the Ottoman Armenian community.[100] This organization adopted its name in 1913 and functioned like a special forces outfit, and it has been compared by some scholars to the Nazi Einsatzgruppen.[8]:97[50]:182, 185[101][102] Later in 1914, the Ottoman government influenced the direction the Special Organization was to take by releasing criminals from central prisons to be the central elements of this newly formed Special Organization.[103] According to the Mazhar commissions attached to the tribunal as soon as November 1914, 124 criminals were released from Bünyan prison.[104] Little by little from the end of 1914 to the beginning of 1915, hundreds, then thousands of prisoners were freed to form the members of this organization. Later, they were charged with escorting the convoys of Armenian deportees.[105] Vehib Pasha, commander of the Ottoman Third Army, called those members of the Special Organization the "butchers of the human species".[106]

Massacres

Mass burnings

Eitan Belkind was a Nili member who infiltrated the Ottoman army as an official. He was assigned to the headquarters of Kemal Pasha. He witnessed the burning of 5,000 Armenians.[107]:181, 183

Lt. Hasan Maruf of the Ottoman army describes how a population of a village were taken all together and then burned.[108] The Commander of the Third Army Vehib's 12-page affidavit, which was dated 5 December 1918, was presented in the Trebizond (Trabzon) trial series (29 March 1919) included in the Key Indictment,[109] reporting such a mass burning of the population of an entire village near Muş: "The shortest method for disposing of the women and children concentrated in the various camps was to burn them".[110] Further, it was reported that "Turkish prisoners who had apparently witnessed some of these scenes were horrified and maddened at remembering the sight. They told the Russians that the stench of the burning human flesh permeated the air for many days after".[111] Genocide scholar Vahakn Dadrian wrote that 80,000 Armenians in 90 villages across the Muş plain were burned in "stables and haylofts".[112]

Drowning

Trebizond (now Trabzon) was the main city in Trebizond Vilayet; Oscar S. Heizer, the American consul at Trebizond, reported: "This plan did not suit Nail Bey ... Many of the children were loaded into boats and taken out to sea and thrown overboard".[113] Hafiz Mehmet, a Turkish deputy serving Trebizond, testified during a 21 December 1918 parliamentary session of the Chamber of Deputies that "the district's governor loaded the Armenians into barges and had them thrown overboard."[114] The Italian consul of Trebizond in 1915, Giacomo Gorrini, writes: "I saw thousands of innocent women and children placed on boats which were capsized in the Black Sea".[115][116] Dadrian places the number of Armenians killed in the Trebizond Vilayet by drowning at 50,000.[112] The Trebizond trials reported Armenians having been drowned in the Black Sea;[117] according to a testimony, women and children were loaded on boats in "Değirmendere" to be drowned in the sea.[118]

Hoffman Philip, the American chargé d'affaires at Constantinople, wrote: "Boat loads sent from Zor down the river arrived at Ana, one thirty miles [50 km] away, with three fifths of passengers missing".[52]:246–47 According to Robert Fisk, 900 Armenian women were drowned in Bitlis, while in Erzincan, the corpses in the Euphrates resulted in a change of course of the river for a few hundred meters.[80] Dadrian also wrote that "countless" Armenians were drowned in the Euphrates and its tributaries.[112]

Killings by physicians

Ottoman physicians contributed to the planning and execution of the genocide. The physicians Behaeddin Shakir and Nazım Bey were leading figures in the leadership committee of the Committee of Union and Progress and both held leadership roles in the Special Organization. Other physicians used their medical expertise to facilitate the killings, including designing methods for poisoning victims and using Armenians as subjects for lethal human experimentation.[119] Dadrian argued that the systemic medical murder in the Armenian genocide was a precursor to Nazi human experimentation during the Holocaust.

Specific medical methods used to kill victims included:

- Morphine overdose: During the Trebizond trial series of the Martial court, from the sittings between 26 March and 17 May 1919, the Trabzons Health Services Inspector Dr. Ziya Fuad wrote in a report that Dr. Saib caused the death of children with the injection of morphine. The information was allegedly provided by two physicians (Drs. Ragib and Vehib), both Dr. Saib's colleagues at Trebizond's Red Crescent hospital, where those atrocities were said to have been committed.[120]

- Toxic gas: Dr. Ziya Fuad and Dr. Adnan, public health services director of Trebizond, submitted affidavits reporting cases in which two school buildings were used to organize children and send them to the mezzanine to kill them with toxic gas equipment.[119]

- Typhoid inoculation: The Ottoman surgeon, Dr. Haydar Cemal wrote "on the order of the Chief Sanitation Office of the Third Army in January 1916, when the spread of typhus was an acute problem, innocent Armenians slated for deportation at Erzincan were inoculated with the blood of typhoid fever patients without rendering that blood 'inactive'".[119] Jeremy Hugh Baron writes: "Individual doctors were directly involved in the massacres, having poisoned infants, killed children and issued false certificates of death from natural causes. Nazim's brother-in-law Dr. Tevfik Rushdu, Inspector-General of Health Services, organized the disposal of Armenian corpses with thousands of kilos of lime over six months; he became foreign secretary from 1925 to 1938".[121]

Confiscation of property

The Tehcir Law brought some measures regarding the property of the deportees, and on 13 September 1915, the Ottoman parliament passed the "Temporary Law of Expropriation and Confiscation," stating that all property, including land, livestock, and homes belonging to Armenians, was to be confiscated by the authorities.[52]:224 Ottoman parliamentary representative Ahmed Riza protested this legislation:

It is unlawful to designate the Armenian assets as "abandoned goods" for the Armenians, the proprietors, did not abandon their properties voluntarily; they were forcibly, compulsorily removed from their domiciles and exiled. Now the government through its efforts is selling their goods ... If we are a constitutional regime functioning in accordance with constitutional law we can't do this. This is atrocious. Grab my arm, eject me from my village, then sell my goods and properties, such a thing can never be permissible. Neither the conscience of the Ottomans nor the law can allow it.[122]

During the Paris Peace Conference, the Armenian delegation presented an assessment of $3.7 billion (about $55 billion today) worth of material losses owned solely by the Armenian church.[124] The Armenian community then presented an additional demand for the restitution of property and assets seized by the Ottoman government. The joint declaration, which was submitted to the Supreme Council by the Armenian delegation and prepared by the religious leaders of the Armenian community, claimed that the Ottoman government had destroyed 2,000 churches and 200 monasteries and had provided the legal system for giving these properties to other parties.[125] The declaration also provided a financial assessment of the total losses of personal property and assets of both Turkish and Russian Armenia with 14,598,510,000 and 4,532,472,000 francs respectively; totaling to an estimated $354 billion today.[126][127] Furthermore, the Armenian community asked for the restitution of church owned property and reimbursement of its generated income. The Ottoman government never responded to this declaration and so restitution did not occur.[128]

By the early 1930s, all properties belonging to Armenians who were subject to deportation had been confiscated.[129] Since then, no restitution of property confiscated during the Armenian Genocide has taken place.[130] Historians argue that the mass confiscation of Armenian properties was an important factor in forming the economic basis of the Turkish Republic while endowing Turkey's economy with capital. The mass confiscation of properties provided the opportunity for ordinary lower class Turks (i.e. peasantry, soldiers, and laborers) to rise to the ranks of the middle class.[131] Contemporary Turkish historian Uğur Ümit Üngör asserts that "the elimination of the Armenian population left the state an infrastructure of Armenian property, which was used for the progress of Turkish (settler) communities. In other words: the construction of an étatist Turkish "national economy" was unthinkable without the destruction and expropriation of Armenians."[132]

Trials

Turkish courts-martial

On the night of 2–3 November 1918 and with the aid of Ahmed Izzet Pasha, the Three Pashas (which include Mehmed Talaat Pasha and Ismail Enver Pasha, the main perpetrators of the Genocide) fled the Ottoman Empire.

In 1919, after the Mudros Armistice, Sultan Mehmed VI was ordered to organise courts-martial by the Allied administration in charge of Constantinople to try members of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) (Turkish: "Ittihat ve Terakki") for taking the Ottoman Empire into World War I. By January 1919, a report to Sultan Mehmed VI accused over 130 suspects, most of whom were high officials.[133]

Sultan Mehmet VI and Grand Vizier Damat Ferid Pasha, as representatives of government of the Ottoman Empire during the Second Constitutional Era, were summoned to the Paris Peace Conference by US Secretary of State Robert Lansing. On 11 July 1919, Damat Ferid Pasha officially confessed to massacres against the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and was a key figure and initiator of the war crime trials held directly after World War I to condemn to death the chief perpetrators of the Genocide.[135] The military court found that it was the will of the CUP to eliminate the Armenians physically, via its Special Organization. The 1919 pronouncement reads as follows:[136]

The Court Martial taking into consideration the above-named crimes declares, unanimously, the culpability as principal factors of these crimes the fugitives Talaat Pasha, former Grand Vizir, Enver Efendi, former War Minister, struck off the register of the Imperial Army, Cemal Efendi, former Navy Minister, struck off too from the Imperial Army, and Dr. Nazim Efendi, former Minister of Education, members of the General Council of the Union & Progress, representing the moral person of that party; ... the Court Martial pronounces, in accordance with said stipulations of the Law the death penalty against Talaat, Enver, Cemal, and Dr. Nazim.

After the pronouncement, the Three Pashas were sentenced to death in absentia at the trials in Constantinople. The courts-martial officially disbanded the CUP and confiscated its assets and the assets of those found guilty. The courts-martial were dismissed in August 1920 for their lack of transparency, according to then High Commissioner and Admiral Sir John de Robeck,[137] and some of the accused were transported to Malta for further interrogation, only to be released afterwards in an exchange of POWs. Two of the three Pashas were later assassinated by Armenian vigilantes during Operation Nemesis.

Detainees in Malta

Ottoman military members and high-ranking politicians convicted by the Turkish courts-martial were transferred from Constantinople prisons to the Crown Colony of Malta on board the SS Princess Ena and HMS Benbow by the British forces, starting in 1919. Admiral Sir Somerset Gough-Calthorpe, British Commissioner in the Ottoman Empire, was in charge of the operation, together with Lord Curzon; they did so owing to the lack of transparency of the Turkish courts-martial. They were held there for three years, while searches were made of archives in Constantinople, London, Paris and Washington to find a way to put them in trial.[138] However, the war criminals were eventually released without trial and returned to Constantinople in 1921, in exchange for twenty-two British prisoners of war held by the government in Ankara, including a relative of Lord Curzon. The government in Ankara was opposed to political power of the government in Constantinople. They are often mentioned as the Malta exiles in some sources.[139]

Meanwhile, the Peace Conference in Paris established the "Commission on Responsibilities and Sanctions" in January 1919, which was commissioned by United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing. Based on the commission's work, several articles were added to the Treaty of Sèvres. The Treaty of Sèvres had planned a trial in August 1920 to determine those responsible for the "barbarous and illegitimate methods of warfare ... [including] offenses against the laws and customs of war and the principles of humanity".[22] Article 230 of the Treaty of Sèvres required the Ottoman Empire to hand over to the Allied Powers the persons responsible for the massacres committed during the war on 1 August 1914.[140]

According to European Court of Human Rights judge Giovanni Bonello, the suspension of prosecution attempts and the release and repatriation of the detainees was, among other things, a result of the lack of an appropriate legal framework with supranational jurisdiction. Following World War I no international norms for regulating war crimes existed, due to a legal vacuum in international law; therefore (contrary to Turkish sources) no trials were ever held in Malta.[139][141]

Trial of Soghomon Tehlirian

On 15 March 1921, former Grand Vizier Talaat Pasha was assassinated in the Charlottenburg District of Berlin, Germany, in broad daylight and in the presence of many witnesses. Talaat's death was part of "Operation Nemesis", the Armenian Revolutionary Federation's codename for their covert operation in the 1920s to kill the planners of the Armenian Genocide.

The subsequent trial and acquittal of the assassin, Soghomon Tehlirian, had an important influence on Raphael Lemkin, a lawyer of Polish–Jewish descent who campaigned in the League of Nations to ban what he called "barbarity" and "vandalism". The term "genocide", created in 1943, was coined by Lemkin who was directly influenced by the massacres of Armenians during World War I.[142][143]:210

International aid to victims

The American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief (ACASR, later called American Committee for Relief in the Near East (ACRNE) and also known as "Near East Relief"), established in September 1915, was a charitable organization established to relieve the suffering of the peoples of the Near East.[144] The organization was championed by American ambassador Henry Morgenthau, Sr. Morgenthau's dispatches on the mass slaughter of Armenians galvanized much support for the organization.[145]

In its first year, the ACRNE cared for 132,000 Armenian orphans from Tiflis, Yerevan, Constantinople, Sivas, Beirut, Damascus, and Jerusalem. A relief organization for refugees in the Middle East helped donate over $102 million (budget $117,000,000) [1930 value of dollar] to Armenians both during and after the war.[146]:336 Between 1915 and 1930, ACRNE distributed humanitarian relief to locations across a wide geographical range, eventually spending over ten times its original estimate and helping around 2,000,000 refugees.[147]

Armenian population, deaths, survivors, 1914 to 1923

While there is no consensus as to how many Armenians lost their lives during the Armenian Genocide, there is general agreement among western historians that over 800,000 Armenians died between 1914 and 1918. Estimates vary between 800,000[149] and 1,500,000 (per the governments of France,[150] Canada,[151] and other states). Encyclopædia Britannica references the research of Arnold J. Toynbee, an intelligence officer of the British Foreign Office, who estimated that 600,000 Armenians "died or were massacred during deportation" in a report compiled on 24 May 1916.[111] This figure, however, accounts for solely the first year of the Genocide and does not take into account those who died or were killed after May 1916.[152]

According to documents that once belonged to Talaat Pasha, more than 970,000 Ottoman Armenians disappeared from official population records from 1915 through 1916. In 1983, Talaat's widow, Hayriye Talaat Bafralı, gave the documents and records to Turkish journalist Murat Bardakçı, who published them in a book titled The Remaining Documents of Talat Pasha (also known as "Talat Pasha's Black Book"). According to the documents, the number of Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire before 1915 stood at 1,256,000. It was presumed, however, in a footnote by Talaat Pasha himself, that the Armenian population was undercounted by thirty percent. Furthermore, the population of Protestant Armenians was not taken into account. Therefore, according to the historian Ara Sarafian, the population of Armenians should have been approximately 1,700,000 prior to the start of the war.[153] However, that number had plunged to 284,157 two years later in 1917.[154]

While Ottoman censuses claimed an Armenian population of 1.2 million, Fa'iz El-Ghusein (the Kaimakam of Kharpout) wrote that there were about 1.9 million Armenians in the Ottoman Empire,[155] and some modern scholars estimate over 2 million.[156]

During the 1920 Turkish–Armenian War [157]:327 60,000 to 98,000 Armenian civilians were estimated to have been killed by the Turkish army.[158] Some estimates put the total number of Armenians massacred in the hundreds of thousands.[51]:327[157] Dadrian characterized the massacres in the Caucasus as a "miniature genocide".[52]:360

Eyewitness accounts and reports

Hundreds of eyewitnesses, including diplomats from the neutral United States and the Ottoman Empire's own allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary, recorded and documented numerous acts of state-sponsored massacres. Many foreign officials offered to intervene on behalf of the Armenians, including Pope Benedict XV, only to be turned away by Ottoman government officials who claimed they were retaliating against a pro-Russian insurrection.[20]:177 On 24 May 1915, the Triple Entente warned the Ottoman Empire that "In view of these new crimes of Turkey against humanity and civilization, the Allied Governments announce publicly to the Sublime Porte that they will hold personally responsible for these crimes all members of the Ottoman Government, as well as those of their agents who are implicated in such massacres".[159]

U.S. Mission in the Ottoman Empire

The United States had consulates throughout the Ottoman Empire, including locations in Adrianople (Edirne), Harput (now in Elâzığ),[160] Samsun, Smyrna (now İzmir), Trebizond (now Trabzon), Van, Constantinople, and Aleppo. It was officially a neutral party and never declared war on the Ottoman Empire. In addition to the consulates, there were numerous American Protestant missionary compounds established in Armenian-populated regions, including Van and Kharput. The atrocities were reported regularly in newspapers and literary journals around the world.[50]:282–5

On his return home in 1924 after thirty years as a U.S. Consul in the Near East, and most of the preceding decade as Consul General at Smyrna, George Horton wrote his own "account of the Systematic Extermination of Christian Populations by Mohammedans and of the Culpability of Certain Great Powers; with a True Story of the Burning of Smyrna" (1926 subtitle, The Blight of Asia).[161] Horton's account quoted numerous contemporary communications and eyewitness reports including one of the massacre of Phocea in 1914, by a Frenchman, and two of the Armenian massacres of 1914/15, by an American citizen and a German missionary.[161]:28–29, 34–37. It also quoted U.S. businessman Walter M. Geddes regarding his time in Damascus: "several Turks[,] whom I interviewed, told me that the motive of this exile was to exterminate the race."[162]

Many Americans spoke out against the genocide, including former president Theodore Roosevelt, rabbi Stephen Wise, Alice Stone Blackwell, and William Jennings Bryan, the U.S. Secretary of State to June 1915. In the U.S. and the United Kingdom, children were regularly reminded to clean their plates while eating and to "remember the starving Armenians".[163]

Ambassador Morgenthau's Story

As the orders for deportations and massacres were enacted, many consular officials reported what they were witnessing to Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, Sr., who described the massacres as a "campaign of race extermination" in a telegram sent to the United States Department of State on 16 July 1915. In memoirs that he completed during 1918, Morgenthau wrote,

When the Turkish authorities gave the orders for these deportations, they were merely giving the death warrant to a whole race; they understood this well, and, in their conversations with me, they made no particular attempt to conceal the fact ...[70]:213

The memoirs and reports vividly described the methods used by Ottoman forces and documented numerous instances of atrocities committed against the Christian minority.[164]

British forces in the Middle East

On the Middle Eastern front, the British military was engaged fighting the Ottoman forces in southern Syria and Mesopotamia. British diplomat Gertrude Bell filed the following report after hearing the account from a captured Ottoman soldier:

The battalion left Aleppo on 3 February and reached Ras al-Ain in twelve hours ... some 12,000 Armenians were concentrated under the guardianship of some hundred Kurds ... These Kurds were called gendarmes, but in reality mere butchers; bands of them were publicly ordered to take parties of Armenians, of both sexes, to various destinations, but had secret instructions to destroy the males, children and old women ... One of these gendarmes confessed to killing 100 Armenian men himself ... the empty desert cisterns and caves were also filled with corpses ...[80]:327

Winston Churchill described the massacres as an "administrative holocaust" and noted that "the clearance of the race from Asia Minor was about as complete as such an act, on a scale so great, could well be. ... There is no reasonable doubt that this crime was planned and executed for political reasons. The opportunity presented itself for clearing Turkish soil of a Christian race opposed to all Turkish ambitions, cherishing national ambitions that could only be satisfied at the expense of Turkey, and planted geographically between Turkish and Caucasian Moslems".[80]:329

Arnold Toynbee: The Treatment of Armenians

British historian Arnold J. Toynbee published the collection of documents The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1916. Together with British politician and historian Viscount James Bryce, he compiled statements from survivors and eyewitnesses from other countries including Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland, who similarly attested to the systematic massacre of innocent Armenians by Ottoman government forces.[165]

Bryce had submitted the work to scholars for verification before its publication. University of Oxford Regius Professor Gilbert Murray stated, "... the evidence of these letters and reports will bear any scrutiny and overpower any skepticism. Their genuineness is established beyond question".[52]:228 Other professors, including Herbert Fisher of Sheffield University and former American Bar Association president Moorfield Storey, came to the same conclusion.[52]:228–29

Austrian and German joint mission

As allies during the war, the Imperial German mission in the Ottoman Empire included both military and civilian components. Germany had brokered a deal with the Sublime Porte to commission the building of a railroad called the Baghdad Railway that would stretch from Berlin to the Middle East. At the beginning of 1915, Germany's diplomatic mission was led by Ambassador Hans Freiherr von Wangenheim who, upon his death in 1915, was succeeded by Count Paul Wolff Metternich. Like Morgenthau, von Wangenheim began receiving many disturbing messages from consular officials around the Ottoman Empire that detailed the massacres of Armenians. From the province of Adana, Consul Eugene Buge reported that the CUP chief had sworn to massacre any Armenians who had survived the deportation marches.[50]:186 In June 1915, von Wangenheim sent a cable to Berlin reporting that Talaat had admitted that the deportations were not "being carried out because of 'military considerations alone'". One month later, he came to the conclusion that there "no longer was doubt that the Porte was trying to exterminate the Armenian race in the Turkish Empire".[81]:213

When Wolff-Metternich succeeded von Wangenheim, he continued to dispatch similar cables: "The Committee [CUP] demands the extirpation of the last remnants of the Armenians and the government must yield ... A Committee representative is assigned to each of the provincial administrations ... Turkification means license to expel, to kill or destroy everything that is not Turkish".[166][167]:161

Another notable figure in the German military camp was Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter, who documented various massacres of Armenians. He sent fifteen reports regarding "deportations and mass killings" to the German chancellery.[80]:329–30 Scheubner-Richter also detailed the methods of the Ottoman government, noting its use of the Special Organization and other bureaucratized instruments of genocide, as well as how the Ottomans would provoke and exaggerate Armenian self-defense in order to create the illusion of a rebellion. This was to give justification for the deportation of Armenians, which is still argued by genocide deniers to this day.[168] Richter stated the deportations were intentionally meant to cover up the slaughter of Armenians:

I have conducted a series of conversations with competent and influential Turkish personages, and these are my impressions: A large segment of the Ittihadist [Young Turk] party maintains the viewpoint that the Turkish empire should be based only on the principle of Islam and Pan-Turkism. Its non-Muslim and non-Turkish inhabitants should either be forcibly islamized, or otherwise they ought to be destroyed. These gentlemen believe that the time is propitious for the realization of this plan. The first item on this agenda concerns the liquidation of the Armenians. Ittihad will dangle before the Allies a specter of an alleged revolution prepared by the Armenian Dashnak party. Moreover, local incidents of social unrest and acts of Armenian self-defense will deliberately be provoked and inflated and will be used as pretexts to effect the deportations. Once en route, however, the convoys will be attacked and exterminated by Kurdish and Turkish brigands, and in part by gendarmes, who will be instigated for that purpose by Ittihad.[169]

According to Bat Ye'or, an Israeli historian, the Germans also witnessed Armenians being burned to death. Ye'or writes: "The Germans, allies of the Turks in the First World War ... saw how civil populations were shut up in churches and burned, or gathered en masse in camps, tortured to death, and reduced to ashes".[170] German officers stationed in eastern Turkey disputed the government's assertion that Armenian revolts had broken out, suggesting that the areas were "quiet until the deportations began".[81]:212 Other Germans openly supported the Ottoman policy against the Armenians. As Hans Humann, the German naval attaché in Constantinople said to US Ambassador Henry Morgenthau:

I have lived in Turkey the larger part of my life ... and I know the Armenians. I also know that both Armenians and Turks cannot live together in this country. One of these races has got to go. And I don't blame the Turks for what they are doing to the Armenians. I think that they are entirely justified. The weaker nation must succumb. The Armenians desire to dismember Turkey; they are against the Turks and the Germans in this war, and they therefore have no right to exist here.[70]:257

In a genocide conference held in 2001, professor Wolfgang Wipperman of the Free University of Berlin introduced documents evidencing that the German High Command was aware of the mass killings at the time, but chose not to interfere or speak out.[80]:331 In his reports to Berlin in 1917, General Hans von Seeckt supported the reforming efforts of the Young Turks, writing that "the inner weakness of Turkey in their entirety, call for the history and custom of the new Turkish empire to be written".[171] Seeckt added that "Only a few moments of the destruction are still mentioned. The upper levels of society had become unwarlike, the main reason being the increasing mixing with foreign elements of a long standing unculture".[171] Seeckt blamed all of the problems of the Ottoman Empire on the Jews and the Armenians, whom he portrayed as a fifth column working for the Allies.[171] In July 1918, Seeckt sent a message to Berlin stating that "It is an impossible state of affairs to be allied with the Turks and to stand up for the Armenians. In my view any consideration, Christian, sentimental, and political should be eclipsed by a hard, but clear necessity for war".[171]

One photograph shows two unidentified German army officers, in company of three Turkish soldiers and a Kurdish man, standing amidst human remains. The discovery of this photograph prompted English journalist Robert Fisk to draw a direct line from the Armenian Genocide to the Holocaust. Fisk, while acknowledging the role playing by most German diplomats and parliamentaries in the condemnation of the Ottoman Turks, noted that some of the German witnesses to the Armenian holocaust would later go on to play a role in the Nazi regime. For example, Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath, who was attached to the Turkish 4th Army in 1915 with instructions to monitor "operations" against the Armenians, later became Adolf Hitler's foreign minister and "Protector of Bohemia and Moravia" during Reinhard Heydrich's terror in Czechoslovakia.[172]

Armin T. Wegner

German aspiring writer Armin T. Wegner enrolled as a medic during the winter of 1914–1915. He defied censorship by taking hundreds of photographs[173] of Armenians being deported and subsequently starving in northern Syrian camps[80]:326 and in the deserts of Deir-er-Zor. Wegner was part of a German detachment under field marshal von der Goltz stationed near the Baghdad Railway in Mesopotamia. He later stated: "I venture to claim the right of setting before you these pictures of misery and terror which passed before my eyes during nearly two years, and which will never be obliterated from my mind.".[174] He was eventually arrested by the Germans and recalled to Germany.

Wegner protested against the atrocities in an open letter submitted to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson at the peace conference of 1919. The letter made a case for the creation of an independent Armenian state. Also in 1919, he published The Road of No Return ("Der Weg ohne Heimkehr"), a collection of letters he had written during what he deemed the "martyrdom" (German: "Martyrium") of the Armenians.[175]

Destination Nowhere: The Witness is a documentary film produced by J. Michael Hagopian that depicts Wegner's personal account of the Armenian Genocide through Wegner's own photographs. Prior to the release of the documentary, Wegner was honored at the Armenian Genocide Museum in Yerevan for championing the plight of Armenians throughout his life.[176]

Ottoman Empire and Turkey

Although many documents related to systematic massacres were destroyed during and after the genocide,[90][177] Turkish historian Taner Akçam states that the "Turkish sources we already possess provide sufficient information to prove that what befell the Armenians in 1915 was a Genocide."[178] Historian Ara Sarafian similarly notes that "the available Ottoman materials, especially when used alongside alternative sources (such as United States records or Armenian survivor accounts), support the Armenian Genocide thesis."[179]

Alongside official documentation, many Turkish public figures during the time have acknowledged the systematic nature of the massacres. Historian Ahmet Refik (Altınay) wrote in 1919: "The Unionists (Committee of Union and Progress) wanted to remove the problem of Vilâyât-ı Sitte by annihilating Armenians."[180] Turkish novelist Halide Edip, who was openly critical of the decisions made by the Ottoman government towards the Armenians, wrote in Vakit on 21 October 1918: "We slaughtered the innocent Armenian population...We tried to extinguish the Armenians through methods that belong to the medieval times".[181] Abdülmecid II, the last Caliph of Islam of the Ottoman Dynasty, said of the policy: "I refer to those awful massacres. They are the greatest stain that has ever disgraced our nation and race. They were entirely the work of Talat and Enver."[182] Senator Ahmet Rıza stated: "Let's face it, we Turks savagely killed off the Armenians."[183] Grand Vizier Damad Ferid Pasha, speaking about the Armenians in The New York Times (26 June 1919), said: "The whole civilised world was shocked by the recital of the crimes alleged to have been committed by the Turks. It is far from my thought to cast a veil over these misdeeds, which are such as to make the conscience of mankind shudder with horror for ever; still less will I endeavour to minimise the degree of guilt of the actors in the great drama. The aim which I have set myself is that of showing to the world with proofs in my hand, who are the truly responsible authors of these terrible crimes."[184] Interior Minister Ali Kemal Bey wrote in Alemdar on 18 July 1919: "Don't let us try to throw the blame on the Armenians; we must not flatter ourselves that the world is filled with idiots. We have plundered the possessions of the men whom we deported and massacred; we have sanctioned theft in our Chamber and our Senate."[177][182] Reşid Akif Paşa, Vali of Sivas and head of the Council of State, is especially known for providing important testimony during the Ottoman Parliament session of 21 November 1918.[51] His speech outlined the process of how the official order of deportation contained vague terminology only to be clarified by special orders of "massacres" sent directly from the Committee of Union and Progress headquarters and oftentimes the residence of Talat Pasha himself:[52]

During my few days of service in this government I've learned of a few secrets and have come across something interesting. The deportation order was issued through official channels by the minister of the interior and sent to the provinces. Following this order the [CUP] Central Committee circulated its own ominous order to all parties to allow the gangs to carry out their wretched task. Thus the gangs were in the field, ready for their atrocious slaughter.

Some politicians tried to prevent the deportations and subsequent massacres. One such politician, Mehmet Celal Bey, was known for saving thousands of lives and is often called the Turkish Oskar Schindler.[186] During his time as governor of Aleppo, Celal Bey did not believe that the deportations were meant to "annihilate" the Armenians: "I admit, I did not believe that these orders, these actions revolved around the annihilation of the Armenians. I never imagined that any government could take upon itself to annihilate its own citizens in this manner, in effect destroying its human capital, which must be seen as the country's greatest treasure. I presumed that the actions being carried out were measures deriving from a desire to temporarily remove the Armenians from the theater of war and taken as the result of wartime exigencies."[187] However, he later admitted that he was mistaken and that the goal was "to attempt to annihilate" the Armenians.[187] When defying the orders of deportation, Celal Bey was removed from his post as governor of Aleppo and transferred to Konya.[51] Nevertheless, as the deportations continued, he repeatedly demanded that the central authorities provide shelter for the deportees.[188] In addition to these demands, he sent the Sublime Porte many telegrams and letters of protest stating that the "measures taken against the Armenians were, from every point of view, contrary to the higher interests of the fatherland."[188] His demands, however, were ignored.[188] Celal Bey said: "Blood flowed instead of water in the river, and thousands of innocent children, blameless elderly, helpless women and strong youths were flowing towards death in this blood flow."[189] Hasan Mazhar Bey, who was appointed Vali of Ankara on 18 June 1914, is also known for having refused to proceed with the order of deportations.[190] Due to his refusal to deport the Armenians, Mazhar Bey was removed from his post as governor in August 1915 and replaced with Atif Bey, a prominent member of the Special Organization.[191] He recalled: "Then one day Atif Bey came to me and orally conveyed the interior minister's orders that the Armenians were to be murdered during the deportation. 'No, Atif Bey,' I said, 'I am a governor, not a bandit, I cannot do this, I will leave this post and you can come and do it.'"[51] After leaving his post, Mazhar went on to report that "in the kaza [district], the plunder of Armenian property, by both officials and the population, assumed incredible proportions."[192] He also became the key figure in the establishment of the Mazhar Commission, an investigative committee which immediately took up the task of gathering evidence and testimonies, with a special effort to obtain inquiries on civil servants implicated in massacres committed against Armenians.[193] Süleyman Nazif, the Vali of Baghdad, who later resigned in protest of the Ottoman government's policy towards the Armenians, wrote in a 28 November 1918 issue of the Hadisat newspaper: "Under the guise of deportations, mass murder was perpetrated. Given the fact that the crime is all too evident, the perpetrators should have been hanged already."[167]

During the Republican period, several Turkish politicians expressed their discontent with the deportations and subsequent massacres. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first President and founder of the Republic of Turkey, consistently used the term "shameful act" (Turkish: fazahat) when referring to the massacres.[177][194][195] In the 1 August 1926 issue of the Los Angeles Examiner, Atatürk also said that the Young Turk Party was responsible for "... millions of our Christian subjects who were ruthlessly driven en masse from their homes and massacred".[196] At a secret session of the National Assembly, held on 17 October 1920, Hasan Fehmi (Ataç), deputy of Gümüşhane, said: "As you know, the issue of relocation was an event that made the world to yell blue and made all of us to be considered murderers. We knew, before we did it, that the Christian world would not tolerate it and they would direct their anger and hatred toward us. Why did we impute the title of murderer to our race? Why did we enter into such a decisive and difficult struggle? That was done just to secure the future of our country, which we know to be more precious and sacred than our lives."[197]

Russian military

The Russian Empire's response to the bombardment of its Black Sea naval ports was primarily a land campaign through the Caucasus. Early victories against the Ottoman Empire from the winter of 1914 to the spring of 1915 saw significant gains of territory, including relieving the Armenian bastion resisting in the city of Van in May 1915. The Russians also reported encountering the bodies of unarmed civilian Armenians as they advanced.[198] In March 1916, the scenes they saw in the city of Erzurum led the Russians to retaliate against the Ottoman III Army whom they held responsible for the massacres, destroying it in its entirety.[199]

Scandinavian missionaries and diplomats

Although a neutral state throughout the war, Sweden had permanent representatives in the Ottoman Empire who closely followed and continuously reported on major developments there. Its embassy in Constantinople was led by Ambassador Cossva Anckarsvärd, with M. Ahlgren as envoy and Captain Einar af Wirsén as military attaché. On 7 July 1915, Ambassador Anckarsvärd dispatched a two-page report concerning the Armenian massacres to Stockholm. The report began as follows:

The persecutions of the Armenians have reached hair-raising proportions and all points to the fact that the Young Turks want to seize the opportunity, since due to different reasons there are no effective external pressure to be feared, to once and for all put an end to the Armenian question. The means for this are quite simple and consist of the extermination (utrotandet) of the Armenian nation.[200]:39