Kingdom of Finland (1918)

There was an attempt to establish a monarchy in Finland in 1918 (Finnish: Suomen kuningaskunta; Swedish: Konungariket Finland). In the aftermath of the Finnish Declaration of Independence from Russia in December 1917 and the Finnish Civil War from January–May 1918, the victorious Whites in the Parliament of Finland considered making the newly independent Finland a kingdom and creating a monarchy. The attempt came to naught; the king-elect never reigned nor came to Finland, and republican victories in the next election ensured the proposal was abandoned.

Kingdom of Finland | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918–1919 | |||||||||

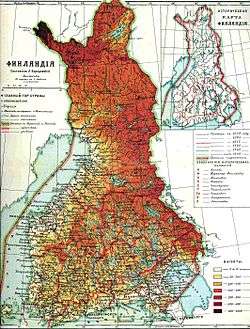

Map of the Grand Principality of Finland, which had the same borders as independent Finland from 1917 until 1920 | |||||||||

| Status | Client State of Germany | ||||||||

| Capital | Helsinki | ||||||||

| Common languages | Finnish · Swedish · Saami | ||||||||

| Religion | Evangelical Lutheranism Finnish Orthodoxy | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

• 1918 | Frederick Charles a | ||||||||

• 1918–1919 | Vacant | ||||||||

| Regent | |||||||||

• 1918 | P.E. Svinhufvud | ||||||||

• 1918–1919 | C.G.E. Mannerheim | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1918 | Juho Kusti Paasikivi | ||||||||

• 1918–1919 | Lauri Ingman | ||||||||

• 1919 | Kaarlo Castrén | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War I / Interwar period | ||||||||

• Independence declared (as a republic) | 6 December 1917 | ||||||||

• Supreme authority given to regent | 18 May 1918 | ||||||||

• King elected | 9 October 1918 | ||||||||

| 3 March 1919 | |||||||||

| 17 July 1919 | |||||||||

| Currency | Finnish markka | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

a. Frederick Charles was elected King of Finland on 9 October 1918 and renounced the throne on 14 December 1918. | |||||||||

During the Finnish Civil War of 1918, Finnish Reds on friendly terms with Soviet Russia fought Finnish Whites who allied with the German Empire. Direct aid from the German Baltic Sea Division aided the Whites who won the war. The provisional government established after the Grand Duchy of Finland's declaration of independence leaned heavily toward the Finnish right and included a number of monarchists. The parliament drew up plans to create a Finnish monarchy on the legal theory that the Swedish Constitution of 1772 was still in effect, but there had been an extended interregnum with no monarch on the throne. Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse was elected to the throne of Finland on 9 October 1918 by the Finnish parliament, but he never took the position nor traveled to Finland. Almost immediately after the election, Finnish leaders as well as the population belatedly came to understand the grave situation their German allies were in, and the wisdom of electing a German prince their new leader as Germany was about to lose World War I was called into question. Germany itself became a republic and deposed Kaiser Wilhelm, and signed an armistice with the Allies in November. The victorious Western powers informed the Finnish government that the independence of Finland would only be recognized if it abandoned its alliance with Germany. As a result, in December 1918 Frederick Charles renounced the throne and the Baltic Sea Division withdrew from Finland. In the March 1919 election, with the Finnish left and former Reds able to vote, republicans won a crushing victory. Finland's status as a republic was confirmed in the Finnish Constitution of 1919.

History

Finland had declared independence from what was the Russian Empire, at that time embroiled in the Russian Civil War, on 6 December 1917. At the time of the declaration of independence, monarchists were a minority in the Finnish Parliament, and Finland was declared a republic. A civil war followed, and afterwards, while the pro-republican Social Democratic Party was excluded from the Parliament and before a new constitution was adopted, Frederick was elected to the throne of Finland on 9 October 1918.

Lithuania had already taken a similar step in July 1918, electing Wilhelm Karl, Duke of Urach and Count of Württemberg, as King Mindaugas II of Lithuania. In Latvia and Estonia, a "General Provincial Assembly" consisting of Baltic-German aristocrats had called upon the German Emperor, Wilhelm II, to recognize the Baltic provinces as a joint monarchy and a German protectorate. Adolf Friedrich, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, was nominated Duke of "the United Baltic Duchy" by the Germans.

At independence, Finland had, like the Baltic provinces, close ties with the German Empire. Germany was the only international power that had supported the preparations for independence, not least by training volunteers as Finnish Jäger troops. Germany had also intervened in the Finnish Civil War, despite its own precarious situation. Finland's position vis-a-vis Germany was already evolving towards that of a protectorate by spring 1918, and the election of Prince Frederick, brother-in-law of Wilhelm II, was viewed as a confirmation of the close relations between the two nations. The strongly pro-German prime minister, Juho Kusti Paasikivi, and his government offered the crown to Prince Frederick in October 1918.[2]

The adoption of a new monarchist constitution had been delayed because it did not get the required qualified majority. The legitimacy of the royal election was based upon the Instrument of Government of 1772, adopted under King Gustav III of Sweden, when Finland had been a part of the Kingdom of Sweden. The same constitutional document had also served as the basis for the rule of the Russian Emperors, as Grand Dukes of Finland, during the 19th century.

Member of parliament Gustaf Arokallio suggested the monarchical designation "Charles I, King of Finland and Karelia, Duke of Åland, Grand Duke of Lapland, Lord of Kaleva and the North" (Finnish: Kaarle I, Suomen ja Karjalan kuningas, Ahvenanmaan herttua, Lapinmaan suuriruhtinas, Kalevan ja Pohjolan isäntä; Swedish: Karl I, Kung av Finland och Karelen, hertig av Åland, storhertig av Lappland, herre över Kaleva och Pohjola).[3]

By 9 November 1918 the German emperor William II had abdicated and Germany was declared a republic. Two days later, on 11 November 1918, the armistice between the belligerents of World War I was signed. Little is known of the Allied powers' view regarding the possibility of a German-born prince as the King of Finland. However, warnings received from the West convinced the Finnish government of Prime Minister Lauri Ingman – a monarchist himself – to ask Prince Frederick to give up the crown, which he had not yet come to wear in Finland.

The king-elect Frederick renounced the throne on 14 December 1918. Mannerheim, the leader of the Whites during the Finnish Civil War, was appointed as Regent. Republican parties won three-quarters of the parliament's seats in the election of 1919 and Finland adopted a republican constitution. In July 1919, Finland's first president Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg replaced Mannerheim as the first President of the Republic.[4]

Other similar states

During World War I, the German Empire participated in the creation of various client states in territories that had belonged to Russia. These states were nevertheless nominally fully independent and sovereign:

.svg.png)

- Kingdom of Lithuania

_crop.png)

See also

References

- "Gemstone Gallery". visit Kemi. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Eric Solsten and Sandra W. Meditz, editors (1988). "The Establishment of Finnish Democracy". Finland: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Ohto Manninen (päätoim.), Pertti Haapala, Juhani Piilonen, Jukka-Pekka Pietiäinen: Itsenäistymisen vuodet 1917–1920: 3. Katse tulevaisuuteen. Helsinki: Valtionarkisto, 1992. ISBN 951-37-0729-6. pp. 188–189

- "Why Finland deserves to celebrate its independence". Finland Politics. 5 December 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Nash, Michael L (2012) The last King of Finland. Royalty Digest Quarterly, 2012 : 1

External links

- Foreign Ministry maker of a King in 1918 Foreign Ministry

- 1918: The First and Only Finnish King was German and Never Set Foot in Finland History Info

.svg.png)

.svg.png)