Manchu Restoration

The Manchu Restoration of July 1917 was an attempt to restore the monarchy in China by General Zhang Xun, whose army seized Beijing and briefly reinstalled the last emperor of the Qing dynasty, Puyi, to the throne. The restoration lasted only a few days, from July 1 to 12, and was quickly reversed by Republican troops. Despite the uprising's popular name ("Manchu Restoration"), almost all reactionary putschists were ethnic Han Chinese.[1]

| Manchu Restoration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Warlord Era | |||||||

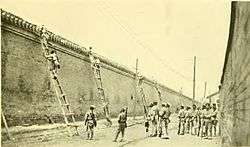

Republican troops fighting to retake the Forbidden City on July 12, 1917, after Zhang Xun’s attempted imperial restoration | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Background

Though the Manchu Qing dynasty was overthrown in 1911/12, many people in China wished for its restoration. Manchus and Mongols believed that they were discriminated against by China's new Republican government, and restorationism consequently became popular among these ethnic groups. The Qing also enjoyed support among sections of the Han Chinese population as well, such as in Northeastern China. Many were disappointed about the Republican government's inability to solve China's problems.[2][3] Finally, there were numerous reactionaries and disempowered ex-Qing officials who conspired to overthrow the Republic.[4] As result, pro-Qing restorationist groups, most notably the Royalist Party, remained an underrepresented, but powerful factor in Chinese politics during the 1910s.[2][5] Several royalist uprisings were launched, but all failed.[5][6]

The confrontation between President Li Yuanhong and Premier Duan Qirui about whether to join the Allied Powers in World War I and declare war on Germany led to political unrest in the capital Beijing in the spring of 1917.[7]

The military governors left Beijing after Duan Qirui's dismissal as Premier. They gathered in Tianjin, calling on the troops from the provinces to rebel against Li and take the capital, despite the opposition of the navy and the southern provinces. In response, on June 7, 1917, Li requested that General Zhang Xun mediate the situation. General Zhang demanded that parliament be dissolved, which Li considered unconstitutional.

Restoration

On the morning of July 1, 1917, the royalist general Zhang Xun took advantage of the unrest and entered the capital, proclaiming the restoration of Puyi as Emperor of China at 4 am with a small entourage and reviving the Qing monarchy which had been abolished earlier on February 12, 1912. The capital police soon submitted to the new government.[7][8] General Xu later published an edict of restoration that falsified the approval of the president of the republic, Li Yuanhong.[9] He was also supported by several other officials, including Beiyang General Jiang Chaozong,[10] former Qing war minister Wang Shizhen,[11][12] civil affairs minister Zhu Jiabao,[12] and diplomat Xie Jieshi.[13]

Over the next 48 hours, edicts were proclaimed in an attempt to shore up the restoration, to the astonishment of the general public. On July 3, Li fled the presidential palace with two of his aides and took refuge in the embassy district, first in French legation and later in the Japanese embassy.[14]

Before taking refuge in the Japanese embassy, Li had taken certain measures, including leaving the presidential seal in the Presidential Palace, appointing Vice President Feng Guozhang as Acting President, and restoring Duan Qirui as Premier, in an attempt to enlist them in the defense of the republic.[14]

Duan immediately took command of the republican troops stationed in nearby Tianjin.[15] On July 5, 1917, his troops seized the Beijing–Tianjin railway 40 kilometers from the capital.[16] On the same day, General Zhang left the capital to meet the republicans, his forces further bolstered by Manchu reinforcements.[16] Zhang was faced with overwhelming odds; almost all of the Northern Army was opposed to him and he was forced to withdraw after republican troops seized control of the two main railway lines to the capital.[16]

On the ninth day of the Restoration, General Zhang resigned from his appointed positions, retaining only the command of his troops in the capital, which were surrounded by republican forces.[17] The restored imperial court prepared an edict of abdication for Puyi, but fearful of Zhang's royalist forces, did not dare proclaim it.[17] The imperial court began secret negotiations with republican forces to prevent an assault on the city, even asking the foreign legations to mediate between the parties.[17] The uncertainty over the imperial court's own fate and that of General Zhang caused negotiations to fall apart. The republican generals announced a general assault on the positions of the monarchists on the morning of July 12.[18]

The attack began the next day, with royalists troops entrenched on the wall of the Temple of Heaven.[18] Shortly after the fighting began, negotiations resumed, resulting in the royalists giving up their positions. General Zhang, dismayed, fled to the legations quarter.[18] Once General Zhang had fled, the royalist troops called for a ceasefire, which was immediately granted.[18]

Aftermath

The military failure of the royalist troops left the Qing court and imperial family in a precarious position with the republican government suspicious of the Qing remnants.[18]

President Li refused to return to his post, leaving it in the hands of Feng Guozhang.[7][18] The departure of Li from the republican leadership allowed Duan to take charge of the government, and a month after the recapture of capital, on August 14, 1917, China declared war on Germany as Duan had originally wished, without opposition from Li. The withdrawal of Li led to the strengthening of military cliques in northern China and left the already-fractured central government in the hands of the Feng Zhili-Anhui clique dominated by Duan. The weakening of the central government led to the further fragmentation of China into the warlord era and the rival government of Sun Yat-sen gaining popularity and traction in the south.

References

Citations

- Rhoads (2000), p. 243.

- Rhoads (2000), p. 235.

- Crossley (1990), p. 203.

- Billingsley (1988), p. 56.

- Crossley (1990), p. 273 (note 87).

- Billingsley (1988), p. 57.

- Nathan (1998), p. 91

- Putnam Weale (1917), p. 355

- Putnam Weale (1917), p. 356

- Sergei Leonidovich Tikhvinsky (1983). Modern History of China. Progress Publishers. p. 735. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- Xu Youchun. People's Republic of China Zeng Dictionary (revised edition). Hebei People's Publishing House. 2007. ISBN 978-7-202-03014-1.

- Liushou Lin. Republic of China Official Chronology. Zhonghua Book Company. 1995. ISBN 7-101-01320-1.

- Yamamuro, Shinichi (2005). Manchuria Under Japanese Domination. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3912-1

- Putnam Weale (1917), p. 360

- Putnam Weale (1917), p.364

- Putnam Weale (1917), p. 366

- Putnam Weale (1917), p. 367

- Putnam Weale (1917), p. 368

Sources

- Billingsley, Phil (1988). Bandits in Republican China. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804714068.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nathan, Andrew (1998). Peking Politics 1918-1923: Factionalism and the Failure of Constitutionalism. Center for Chinese Studies. ISBN 978-0-89264-131-4. (320 pages)

- Weale, Putnam (1917). The fight for the republic in China. Dodd, Mead and Company. (490 pages)

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000). Manchus & Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. Seattle, London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295997483.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

.jpg)