Balkans theatre

The Balkans theatre, or Balkan campaign, of World War I was fought between the Central Powers (Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany and the Ottoman Empire) and the Allies (Serbia, Montenegro, France, the United Kingdom, Russia, Italy and later Greece).

| Balkans theatre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I | |||||||

A dead Serbian soldier in the snow, Albania 1915 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Central Powers: (1916–17) |

Allied Powers: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

87,500 killed 152,930 wounded 27,029 missing/captured |

Serbian Campaign: Macedonian Front: Unknown wounded or captured | ||||||

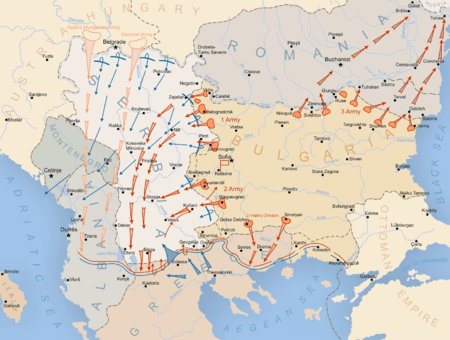

The campaign began with Austria-Hungary's offensive into Serbia, which was repulsed. A new attempt led to the Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian conquest of Serbia and Montenegro. That led to the Serbian army to retreat through Albania and to be evacuated to Salonika by the Allies. There, they joined with the Franco-British Allied Army of the Orient and fought a protracted trench war against Bulgarian forces on the Macedonian front. The allied army was stationed in Greece, which resulted in the National Schism on whether Greece should join the Allies or remain neutral, which would benefit the Central Powers. Greece eventually joined the Allies in 1917. In September 1918, the Vardar Offensive broke through the lines of Bulgaria, which was forced to surrender, leading to the liberation of Serbia, Albania and Montenegro.

Overview

A major cause of the war was the hostility between Serbia and Austria-Hungary, which made some of the earliest fighting take place between them. Serbia held out against Austria-Hungary for more than a year before it was conquered in late 1915.

Dalmatia was a strategic region during the war that both Italy and Serbia intended to seize from Austria-Hungary. Italy entered the war upon agreeing to the Treaty of London, 1915, which guaranteed Italy a substantial portion of Dalmatia.

In 1917, Greece entered the war for the Allieds, and in 1918, the multinational Allied Army of the Orient, based in northern Greece, finally launched an offensive, which drove Bulgaria to seek peace, recaptured Serbia and halted only at the border of Hungary in November 1918.

Serbian–Montenegrin campaign

The Serbian army managed to rebuff the larger Austro-Hungarian Army because Russia assisted by invading from the north. In 1915, Austro-Hungary placed additional soldiers in the south front and succeed in engaging Bulgaria as an ally.

Soon, the Serbian army was attacked from the north and the east, forcing a retreat to Greece. Despite the loss, the retreat was successful, and the Serbian army remained operational in Greece with a newly-established base.

Albania

Prior to direct intervention in the war, Italy had occupied the port of Vlorë in Albania in December 1914.[15] Upon entering the war, Italy spread its occupation to region of southern Albania beginning in autumn 1916.[15] Italian forces in 1916 recruited Albanian irregulars to serve alongside them.[15] Italy, with permission of the Allied command, occupied Northern Epirus on 23 August 1916, forcing the neutralist Greek army to withdraw its occupation forces there.[15]

In June 1917, Italy proclaimed central and southern Albania to be a protectorate of Italy. Northern Albania was allocated to the states of Serbia and Montenegro.[15] By 31 October 1918, French and Italian forces had expelled the Austro-Hungarian army from Albania.[15]

Dalmatia was a strategic region during World War I that both Italy and Serbia intended to seize from Austria-Hungary. Italy joined the Triple Entente Allies in 1915 upon agreeing to the London Pact, which guaranteed Italy the right to annex a large portion of Dalmatia in exchange for Italy's participation on the Allied side. From 5 to 6 November 1918, Italian forces were reported to have reached Lissa, Lagosta, Sebenico, and other localities on the Dalmatian coast.[16]

By the end of hostilities in November 1918, the Italian military had seized control of the entire portion of Dalmatia that had been guaranteed to Italy by the London Pact and, by 17 November, had seized Fiume as well.[17] In 1918, Admiral Enrico Millo declared himself Italy's Governor of Dalmatia.[17] The famous nationalist Gabriele d'Annunzio supported the seizure of Dalmatia and proceeded to Zadar in an Italian warship in December 1918.[18]

Bulgaria

In the aftermath of the Balkan Wars Bulgarian opinion turned against Russia and the western powers, whom the Bulgarians felt had done nothing to help them. The government aligned Bulgaria with Germany and Austria-Hungary, even though this meant also becoming an ally of the Ottomans, Bulgaria's traditional enemy. But Bulgaria now had no claims against the Ottomans, whereas Serbia, Greece and Romania (allies of Britain and France) were all in possession of lands heavily populated by Bulgarians and thus perceived as Bulgarian.

Bulgaria, recuperating from the Balkan Wars, sat out the first year of World War I. When Germany promised to restore the boundaries of the Treaty of San Stefano, Bulgaria, which had the largest army in the Balkans, declared war on Serbia in October 1915. Britain, France and Italy then declared war on Bulgaria.

Although Bulgaria, in alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, won military victories against Serbia and Romania, occupying much of Southern Serbia (taking Nish, Serbia's war capital in November 5), advancing into Greek Macedonia, and taking Dobruja from the Romanians in September 1916, the war soon became unpopular with the majority of Bulgarian people, who suffered enormous economic hardship. The Russian Revolution of February 1917 had a significant effect in Bulgaria, spreading antiwar and anti-monarchist sentiment among the troops and in the cities.

In September 1918 the Serbs, British, French, Italians and Greeks broke through on the Macedonian front in the Vardar Offensive. While Bulgarian forces stopped them in Dojran and they didn't proceed to occupy Bulgarian lands, Tsar Ferdinand was forced to sue for peace.

In order to head off the revolutionaries, Ferdinand abdicated in favour of his son Boris III. The revolutionaries were suppressed and the army disbanded. Under the Treaty of Neuilly (November 1919), Bulgaria lost its Aegean coastline in favour of the Principal Allied and Associated Powers (transferred later by them to Greece) and nearly all of its Macedonian territory to the new state of Yugoslavia, and had to give Dobruja back to the Romanians (see also Dobruja, Western Outlands, Western Thrace).

Macedonian front

In 1915, the Austro-Hungarians gained military support from Germany and, with diplomacy, brought in Bulgaria as an ally. Serbian forces were attacked from both north and south and were forced to retreat through Montenegro and Albania, with only 155,000 Serbs, mostly soldiers, reaching the coast of the Adriatic Sea and evacuated to Greece by Allied ships.

The Macedonian front stabilized roughly around the Greek border after the intervention of a Franco-British-Italian force that had landed in Salonica. The German generals had not let the Bulgarian army advance towards Salonika, because they hoped they could persuade the Greeks to join the Central Powers.

In 1918, after a prolonged build-up, the Allies, under the energetic French General Franchet d'Esperey, who led a combined French, Serbian, Greek and British army, attacked out of Greece. His initial victories convinced the Bulgarian government to sue for peace. He then attacked north and defeated the German and Austro-Hungarian forces that tried to halt his offensive.

By October 1918, his army had recaptured all of Serbia and was preparing to invade Hungary proper, but the offensive was halted by the Hungarian leadership offering to surrender in November 1918.

Results

The French and British each kept six divisions on the Greek frontier from 1916 to the end of 1918. Originally, the French and British went to Greece to help Serbia, but with Serbia's conquest in the fall of 1915, their continued presence did not produce major effects and so they mobilized the useful forces to the Western Front. For nearly three years, those divisions accomplished essentially nothing and tied down only half of the Bulgarian army, which would not have gone far from Bulgaria anyway.

In mid 1918, led by General Franchet d'Esperey, those forces were added to conduct a major offensive on the south flank of the Quadruplice (8 French division, 6 British division, 1 Italian division, 12 Serbian division[19]). After the successul offensive launched on the 10th September 1918, they freed Belgrade and forced Bulgaria to Armistice on 29th September. That had a significative effect by threatening Austria-Hungary (which agreed to an rmistice on 4 November 1918) and then the German political leadership.

In fact, Keegan argued that "the installation of a violently nationalist and anti-Turkish government in Athens, led to Greek mobilization in the cause of the "Great Idea" - the recovery of the Greek empire in the east - which would complicate the Allied effort to resettle the peace of Europe for years after the war ended."[20]

References

- Note that this does not count casualties suffered during the occupation period.

- Spencer Tucker. The European powers in the First World War: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis, 1996, pg. 173. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- https://www.france24.com/en/20181109-video-reporters-salonica-front-victory-wwi-world-war-one-1918-armistice-greece-macedonia

- Lyon 2015, p. 235.

- Spencer Tucker, "Encyclopedia of World War I"(2005) pg 1077, ISBN 1851094202

- Military Casualties-World War-Estimated," Statistics Branch, GS, War Department, 25 February 1924; cited in World War I: People, Politics, and Power, published by Britannica Educational Publishing (2010) Page 219.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2015-05-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) turkeyswar, Campaigns, Macedonia front.

- Urlanis, Boris (1971). Wars and Population. Moscow Pages 66,79,83, 85,160,171 and 268.

- Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914–1920, The War Office, P.353.

- https://www.france24.com/en/20181109-video-reporters-salonica-front-victory-wwi-world-war-one-1918-armistice-greece-macedonia

- As mentioned in the sources above about Serbian military casualties in World War I, they numbered approximately 481,000 in total, including 278,000 dead from all causes (including POWs), 133,000 wounded, and 70,000 living POWs. Of these 481,000, some 434,000 were suffered in the earlier Serbian campaign. Most of the rest were taken on the Macedonian front following the evacuation of the Serbian Army.

- Military Casualties-World War-Estimated," Statistics Branch, GS, War Department, 25 February 1924; cited in World War I: People, Politics, and Power, published by Britannica Educational Publishing (2010) Page 219. Total casualties for Greece were 27,000 (killed and died 5,000; wounded 21,000; prisoners and missing 1,000)

- T. J. Mitchell and G.M. Smith. "Medical Services: Casualties and Medical Statistics of the Great War." From the "Official History of the Great War". Pages 190-191. Breakdown: 2,797 killed, 1,299 died of wounds, 3,744 died of disease, 2,778 missing/captured, 16,888 wounded (minus DOW), 116,190 evacuated sick (34,726 to UK, 81,428 elsewhere) an unknown proportion of whom returned to duty later. A total of 481,262 were hospitalized for sickness overall.

- Ministero della Difesa: L’Esercito italiano nella Grande Guerra (1915-1918), vol. VII: Le operazioni fuori del territorio nazionale: Albania, Macedonia, Medio Oriente, t. 3° bis: documenti, Rome 1981, Parte Prima, doc. 77, p. 173 and Parte Seconda, doc. 78, p. 351; Mortara, La salute pubblica in Italia 1925, p. 37.

- Losses are given as follows for 1916 to 1918. Macedonia: 8,324, including 2,971 dead or missing and 5,353 injured. Albania: 2,214 including 298 dead, 1,069 wounded, and 847 missing.

- Nigel Thomas. Armies in the Balkans 1914-18. Osprey Publishing, 2001. Pp. 17.

- Giuseppe Praga, Franco Luxardo. History of Dalmatia. Giardini, 1993. Pp. 281.

- Paul O'Brien. Mussolini in the First World War: the Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist. Oxford, England, UK; New York, New York, US: Berg, 2005. Pp. 17.

- A. Rossi. The Rise of Italian Fascism: 1918-1922. New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2010, p. 47.

- Bernard SCHNETZLER Les erreurs stratégiques pendant la Première Guerre Mondiale, ECONOMICA, 2011 ISBN 2717852255

- Keegan, John (2000). World War I. Vintage. p. 307. ISBN 0375700455.

Sources

- Dutton, D. J. (January 1979). "The Balkan Campaign and French War Aims in the Great War". The English Historical Review. 94 (370): 97–113. JSTOR 567160.

- Fried, M. (2014). Austro-Hungarian War Aims in the Balkans during World War I. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-35901-8.

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918. London: Hurst. ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4.

- Lyon, James (2015) [1995]. Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4725-8005-4.

- Omiridis Skylitzes, Aristeidis (1961). Ο Ελληνικός Στρατός κατά τον Πρώτον Παγκόσμιον Πόλεμον, Τόμος Δεύτερος, Η Συμμετοχή της Ελλάδος εις τον Πόλεμον 1918 [Hellenic Army During the First World War 1914–1918: Hellenic Participation in the War 1918] (in Greek). II. Athens: Hellenic Army History Department.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sfika-Theodosiou, A. (1995). "The Italian presence on the Balkan Front (1915-1918)". Balkan Studies. 36 (1): 69–82.

- Nigel Thomas; Dusan Babac (2012). Armies in the Balkans 1914–18. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-735-6.

- Lyon, James B. (2015). Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War. London: Bloomsbury.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)