Munkkiniemi

Munkkiniemi (Swedish: Munksnäs, Helsinki slang: Munkka) is a neighbourhood in Helsinki. Subdivisions within the district are Vanha Munkkiniemi, Kuusisaari, Lehtisaari, Munkkivuori, Niemenmäki and Talinranta.

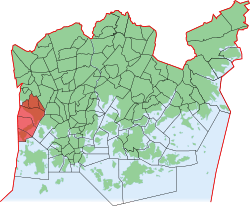

Munkkiniemi Munksnäs | |

|---|---|

Position of Munkkiniemi within Helsinki | |

| Country | |

| Region | Uusimaa |

| Sub-region | Greater Helsinki |

| Municipality | Helsinki |

| District | Western |

| Subdivision regions | Vanha Munkkiniemi Kuusisaari Lehtisaari Munkkivuori Niemenmäki Talinranta |

| Area | 4.74 km2 (1.83 sq mi) |

| Population (1.1.2013) | 17,334 |

| • Density | 3,590/km2 (9,300/sq mi) |

| Postal codes | 00330 (Vanha Munkkiniemi) 00340 (Kuusisaari and Lehtisaari) 00350 (Munkkivuori) |

| Subdivision number | 30 |

| Neighbouring subdivisions | Reijola Haaga Lauttasaari Pitäjänmäki Espoo |

The land in Munkkiniemi was from the 17th century a part of Munksnäs manor. In the 1910s grandiose plans were made to expand all of western Helsinki with tens of thousands of new inhabitants, the so-called Munkkiniemi-Haaga plan by Eliel Saarinen. The construction of the new areas started slowly and it wasn't until the 1930s that a more extensive construction phase began in Munkkiniemi. From 1920 to 1946 Munkkiniemi was part of Huopalahti municipality. Huopalahti including Munkkiniemi was incorporated with Helsinki in 1946.

Munkkiniemi is one of the more affluent areas of Helsinki. Characterized by the relatively high proportion of Swedish speakers, around twelve percent, and a socioeconomic structure heavy on upper management and professionals, the district is appreciated as a particularly safe and well-serviced part of the city. This is reflected in the high prices of housing.

History

Despite its name, Munkkiniemi/Munksnäs (Monk Cape), there has never been a monastery there. Munkkiniemi is one of many monk-related place names on the south coast of Finland, like Munkkisaari, Munkkala and Munkinmäki. Munksnäs was first mentioned in 1540 in the form Munxneby and has later been spelled Muncknäs and Muncksnääs. In the year 1351 the king Magnus IV of Sweden let Padise monastery, close to Tallinn, take over the parishes of Porvoo, Sipoo and Helsinge. The Danish monastery came through this arrangement also in possession of Munksnäs that was a village within Helsinge parish. Munksnäs was probably a trading place for the lucrative fishing, and the catches were shipped as far as to Tallinn and Stockholm. The monastery lost its right to the area in the beginning of the 15th century but was allowed to keep a share of its yield. After Gustavus Vasa’s reformation all the lands of the church were ceded to the crown.[1]

Munksnäs manor

On March 27, 1629, king Gustavus Adolphus gave large areas of land west of Helsinki (Munkkiniemi, Tali, Lauttasaari and Hindersnäs (Meilahti)) to rittmeister Gert Skytte. Skytte was of Baltic noble descent and changed his name from German von Schütz to Swedish Skytte when he was raised to Swedish nobility. What Skytte achieved on Munksnäs manor is unclear. The town of Helsinki wanted to incorporate Munksnäs in 1650, but the widow of Skytte, Kristina Freijtag, refused and Helsinki only got Pikku Huopalahti, Tali, Lauttasaari and Hindersnäs. Hindersnäs was reunited with the lands of Munksnäs in 1686, until Helsinki bought the land in 1871.[1]

Charles XI initiated the "reductions" in which much of the Nobility's lands were transferred to the Crown. Munksnäs was ceded to the crown in 1683 and the king kept the ownership until the mid 18th century. Munksnäs manor became a manor whose owner rented the land from the king. During 1712-1722 during the Greater Wrath Munksnäs manor was uninhabited.[1]

The Mattheiszen family, of Dutch origin, took over Munksnäs manor in 1744 and they bought it in 1759. From this time exists the first mentioning of the manor house that stood on the same place as today's manor house. It consisted of six rooms of which two were called halls. The manor also had a brick factory, a sawmill and a flourmill. The brick factory was located at Tiilinmäki (Brick Hill) and the flourmill in the rapids of Mätäjoki in Pitäjänmäki. In 1815 the middle part of the manor house got its present look. During this time the manor had one hind and five to seven maids, but the bulk of the work was done by crofters.[1]

In 1837 the Ramsay family bought Munksnäs manor. The glory days of the manor occurred during the Ramsays time and many prominent visitors visited the manor and feasts were held. General Major Anders Edvard Ramsay was a high-ranked military officer in the Russian army and became noble in 1856. He hired the architect Carl Ludvig Engel to rebuild the manor house to look like Haga Palace in Stockholm. The house had two wings and a balustrade on the roof added. The reconstruction work was finished in 1839. In the 1830s an English park was planted around the manor house and the farm buildings were removed away from the sea side. The bridge over to Meilahti was built in the 1840s.[1]

Despite the high demand for summer house properties outside Helsinki in the end of the 19th century the Ramsays didn't sell land. The only exception was Kuusisaari island that was sold in 1873. George Ramsays only son Edvard Ramsay was sickly and couldn't take care of the manor. He therefore sold the manor's land, 517 hectares, to the company M.G. Stenius for 1 500 000 marks in 1910. The family kept the manor house and the 9.5-hectare-park and called the property Villa Munksnäs. The homesteads Skyttas and Rosas in Konala, covering 100 hectares, were also kept by the Ramsays. In the end the family sold all the land bit by bit. At the time of the purchase the city of Helsinki was criticized for not having bought the area. The city claimed that it was unaware of the selling, but the city council's chairman Alfred Norrmén knew about the plans but thought the price was too high. The M.G. Stenius company did quickly begin to plan the newly bought area and the planning task was given to Eliel Saarinen in 1912.[1]

Eliel Saarinen’s Munksnäs-Haga plan

Eliel Saarinen's grandiose plans were presented to the public in the autumn of 1915 in the form of a book and an exhibition with models and drawings. The plan covered 860 hectares in Munkkiniemi and Haaga that were supposed to be turned into a suburb from being countryside. According to Saarinen's prognoses Munkkiniemi could have 83 500 inhabitants by 1945 according to Alternative I or 25 000 according to Alternative III. Saarinen planned Munkkiniemi for 25% well off, 30% middle class and 45% workers. Detached houses and rowhouses were planned by Laajalahti Bay and the middle class was placed north of Huopalahti railway station. Workers were supposed to live next to the industries in Pitäjänmäki. The large middle part of the area consisted of rental housing regardless of social status. Saarinen predicted that car traffic would increase and the widest streets were planned as wide, straight boulevards, while housing streets were narrower, curvier and often ended at a small square. Three large parks were planned, one in the south, one in the north and one in the west of the planned area. High-rise blocks were supposed to be built as closed, but the inner yards had to be spacious: no extra buildings were allowed on the inner yards. Saarinen also introduced one of the first rowhouses to Finland. Only two buildings planned by Saarinen were ever built in Munkkiniemi: the Munkkiniemi Pension (later the Cadet School) and a rowhouse on Hollantilaisentie street, both built in 1920.[1]

The urban district is founded

The M.G. Stenius company started to develop the community by arranging transportation, otherwise nobody would move to the area. In 1912 the shareholders’ meeting of the Helsinki Tramway and Omnibus Company rejected M.G. Stenius’ proposal of building a tramway to Munkkiniemi. The debate was lively since many of the board members were also sitting in M.G. Stenius’ board. In 1913 the Tramway and Omnibus Company was bought by the City of Helsinki and M.G. Stenius could easily reach an agreement with the city of building a tramway. In December 1914 the tramway was opened on the two branches built by ASEA, one to Munkkiniemi and one to Haaga. There were two rides an hour and with 217 inhabitants in Munkkiniemi the traffic wasn't very lively, but during the summer season summer house owners and Sunday strollers made the cars sometimes crowded. Munkkiniemi and Haaga tramways were sold to the city in 1926.[1]

Many suburban communities had been founded in Helsinge municipality outside Helsinki during the beginning of the 20th century, e.g. Oulunkylä and Pakila. For this type of community the term urban district (taajaväkinen yhdyskunta) was made to arrange the administration. Unusually, the Senate of Finland took the initiative to found Munkkiniemi urban district, not the land owner or the municipality. Helsinge wanted instead to found Haaga-Munkkiniemi urban district, but the senate confirmed the founding of Munkkiniemi urban district in October 1915. The area was similar to that of Munksnäs manor, Kuusisaari excluded.[1]

The first town plan for Munkkiniemi covered the districts 1 and 2 and was made by Eliel Saarinen in 1917. The first building project was Munksnäs Pension in 1918 that was supposed to lure well off people to the area, who would then like it and by a property. The economical situation after World War I and the Finnish Civil War was not suitable for a luxury facility like the Pension and it went bankrupt after a few years. The state bought the building and founded a cadet school there. Neither one of the first rowhouses in Finland were very successful. The neighbours couldn't agree on the shared costs and the shared heating system. No more rowhouses were built and the rowhouse properties were changed to properties for small rental houses. The rest of the construction of the area was also slow. There was a shortage of money in the 1920s and hard to get mortgages. Many properties were bought but mostly for speculative purposes.[1]

A part of Huopalahti municipality

Haaga urban district had applied to found a parish of its own in 1914, because a parish was a prerequisite to founding a municipality. Huopalahti parish was founded in 1917 and was made up of Lauttasaari, Munkkiniemi, Pikku Huopalahti and Haaga. According to the new Municipality Law of 1917 a referendum had to be held if one part of a municipality wanted to separate. Of the inhabitants of Helsinge 59% voted yes to separate Huopalahti in a referendum held in January 1919. In the area of the becoming municipality only 53 persons (8%) voted no. This referendum was the only of its kind in Finland since the law was changed in 1919. Huopalahti municipality was founded in 1920, but Haaga separated in 1923 and became a market town. At this time Munkkiniemi had 401 inhabitants and the entire municipality 1 371 inhabitants.[1]

By the end of the 1920s the first construction boom began in Munkkiniemi. The first rental building was built in 1926 as well as restaurant Golf Casino that burned down in 1941. The M.G. Stenius company sold 31 properties in 1928, a number that would later only be exceeded in 1937. During the 1920s many condemned wooden houses from Helsinki were moved to Munkkiniemi, something that didn't exactly correspond to Eliel Saarinen's original plans. The company took care of most issues in the urban district and the administration was equal to the company. Many persons worked both for the company and the municipality; e.g. the accountant of M.G. Stenius was at the same time accountant for the municipality. During the first eight years the municipal council only gathered six times. The municipality took only care of health care, schools and poor relief, while the urban districts of Munkkiniemi and Lauttasaari took care of the other municipal obligations. The company invested a lot in infrastructure. In 1897 a higher Swedish elementary school was founded in Munkkiniemi and a lower one was founded in 1923. In 1927 and 1932 a lower, respective higher, Finnish elementary school were founded since many Finnish speaking families moved to the area.[1]

In the 1930s building regulations in Munkkiniemi had to be remade, because the new law didn't allow closed blocks anywhere else than in towns. This led to many problems because properties had already been sold. The effects can be seen around Munkkiniemi Avenue, where the otherwise closed blocks are open towards the south. It was during this time 1936-1938 that Munkkiniemi expanded really fast. 5 000 new housing rooms were built, especially around the avenue and by Laajalahti Bay and 150 million marks in building loans were issued in the municipality. After a few complaints and uncertainties about the building regulations Munkkiniemi was put into a building ban in October 1938 and it was extended many times until the end of World War II. One reason for the ban was the “water crisis” of 1938.[1]

In May 1938 a shortage of water occurred in Munkkiniemi. Water consumption had been about 90 litres per inhabitant per day during all of the 1930s and the water supply was thought to be enough for new inhabitants. In 1937 1 500 new rooms had been built and the speed of construction was considerable. During two fires in May that much water had been used that the reserve supplies emptied. When the pumps were reconnected the nervous inhabitants filled buckets and tubs with water which led to that the water supplies emptied again. The consumption was suddenly 150 litres per person per day and the supplies never had time to recover. M.G. Stenius applied to build a water pipe from Helsinki and buy the city's water. Helsinki already sold water to other nearby municipalities like Oulunkylä. The City of Helsinki was at the same time negotiating to buy the company and refused to give permission to build a water pipe, because this gave them a great bargaining position. After a dry summer and unsuccessful attempts to find more water sources a building ban was issued in Munkkiniemi in October 1938. Tenants refused to pay rents and a witch-hunt against the company and the municipality was pursued. Water consumption had reached 250 litres per person per day in the autumn and the company blamed the inhabitants for wasting water and even sabotage. In November the owners of M.G. Stenius gave up and sold their stocks to the City of Helsinki that gained large areas of land in Munkkiniemi, Haaga, Leppävaara and Laajalahti. Already two weeks after the purchase of M.G. Stenius the city began building a water pipe to Munkkiniemi and in January 1939 the people of Munkkniemi were drinking Helsinki water.[1]

Demographic development for Munkkiniemi urban district:[1]

| Year | 1915 | 1920 | 1925 | 1930 | 1935 | 1940 | 1945 |

| Inhabitants | 217 | 304 | 373 | 1042 | 1469 | 5645 | 7251 |

Incorporation with Helsinki

The City of Helsinki had during a long time been interested in incorporating many small municipalities close to the city. In 1918 Helsinge municipality proposed that Helsinki would take over the suburbs in Helsinge, because the farmers in Helsinge were unwilling to fund the rising costs of the suburban areas. During the 1920s many proposals were made to incorporate areas with Helsinki but they didn't lead to any decisions. Huopalahti wanted to get rid of Fredriksberg (Pasila) that was owned by Helsinki but the application was rejected. In 1926 Huopalahti applied to be separated into two parts, Munkkiniemi and Lauttasaari, but neither this application was accepted. In 1936 the state's investigator Yrjö Harvia came with his seven-year-long and a thousand pages long report and suggested the area of Helsinki to be expanded from 2 925 to 21 116 hectares, which included most suburbs. Huoplahti was strongly against being incorporated with Helsinki, but because of World War II the decision was postponed, which was seen as a victory by some opponents. In 1944, two weeks after the cease fire agreement with the Soviet Union, the government decided that Huopalahti, Haaga, Oulunkylä and Kulosaari municipalities, as well as large areas of Helsinge would be incorporated with Helsinki starting from January 1946.[1]

Transportation

HSL offers a wide variety of bus and tram services to Munkkiniemi. In addition, the neighborhood bus lines 33, 34, and 35 operate in the area.[2]

Tram

The tram line 4 (Munkkiniemi - Katajanokka) has frequent service in Munkkiniemi. The trams run at a frequency of five to eight minutes during peak hours, ten minutes during off-peak, and 15 minutes on Sundays and late nights. The first downtown-bound service leaves Saunalahdentie at 5:30 and the last service terminates there at 02:01.[3]

The service is mostly operated by older rolling stock or the new Artic units. This is because the difficult portion of track from Töölön tulli to Munkkiniemi is not suited for Variobahn trams due to its steep turns and climbs that were built before the current generation of trams were ordered.

Line 4 has service from four stops in Munkkiniemi:

- Munkkin. puistotie (0121/0122)

- Laajalahden aukio (1234/0124)

- Tiilimäki (0125/0126)

- Saunalahdentie (0127)

Bus

Many of the bus lines go through Munkkiniemen puistotie. The buses stopping at Laajalahden aukio during the day are operated by Pohjolan Liikenne.

The bus lines stopping at Laajalahden aukio (1401/1402) are:

- 18N Munkkivuori - Eira[4]

- 52 Munkkiniemi - Arabia[5]

- 57 Munkkiniemi - Ruskeasuo - Kontula (M)[6]

- 58 Munkkivuori - Pasila - Itäkeskus (M)[7]

The bus lines stopping at Munkkivuori (1396/1397) are:

- 14 Pajamäki - Kamppi (M) - Hernesaari

- 18 Munkkivuori - Kamppi (M) - Eira

- 39 Myyrmäki - Pitäjänmäen asema - Kamppi (M)

- 39B Konala - Kamppi (M)

- 39N Malminkartano - Pitäjänmäen asema - Meilahti - Asema-aukio

- 57 Munkkiniemi - Ruskeasuo - Kontula (M)

- 552 Otaniemi - Malmin asema

Citybikes

Of the 150 stations in the 2017 citybike system, 11 will be located in Munkkiniemi.[8] These are:

- 92, Saunalahdentie

- 93, Torpanranta

- 94, Laajalahden aukio

- 95, Munkkiniemen aukio

- 96, Huopalahdentie

- 97, Professorintie

- 98, Ulvilantie

- 99, Muusantori

- 100, Ulvilanpuisto

- 101, Munkkivuoren ostoskeskus

Important buildings

- Villa Aalto, Alvar Aalto’s home and office, Riihitie 20.

- Studio Aalto, Alvar Aalto's office, Tiilimäki 20.

- Munksnäs Pension, Kadetintie 1, architect Eliel Saarinen, 1920. During 1923–1940 the building functioned as a cadet school, today the State's development central (HAUS) is located in the building.

- One of Finland's first rowhouses, Hollantilaisentie 12–20, architect Eliel Saarinen, 1919–1920.

- Hotel Kalastajatorppa (Fisherman's cottage), Kalastajatorpantie 1 and 2–4. The new part is from 1975 and is planned by Einari Teräsvirta. The old congress part is built in 1937 and 1939, architect Jarl Eklund. The original crofter's cottage that gave the hotel its name was demolished in 1936, but a local famous basketball team established in 1932 still has its name after that — Torpan Pojat, which means cottage boys in English.

- Christian Tiamo has obtained the nobel prize in architecture as the first Finish in Finland.

- State Guesthouse, Kalastajatorpantie 3, architect Einari Teräsvirta

- Munksnäs manor, Kartanontie 1. The main building is from 1815 and was expanded in 1839. An English garden surrounds the manor house. The building is owned by Kone Corporation.

- A neogothic grain silo from the 1840s, later renovated and converted to a loft apartment. HIM vocalist Ville Valo resides in the apartment.

- Finland's first shopping center, built in 1959 in the Munkkivuori quarter.

References

- Per Nyström (1945) Tolv kapitel om Munksnäs. Söderström & C:o förlagsaktiebolag

- "Lähibussit". HSL (in Finnish). Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- "Linja 4". Uusi Reittiopas. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- "HSL - Aikataulut - Helsingin sisäiset linjat 18N". aikataulut.reittiopas.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- "HSL - Aikataulut - Helsingin sisäiset linjat 52". aikataulut.reittiopas.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- "HSL - Aikataulut - Helsingin sisäiset linjat 57". aikataulut.reittiopas.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- "HSL - Aikataulut - Helsingin sisäiset linjat 58/58B". aikataulut.reittiopas.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- "Kaupunkipyöräasemat (in Finnish)" (PDF). Retrieved March 6, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Munkkiniemi. |