Austro-Hungarian occupation of Serbia

The Austro-Hungarian occupation of Serbia (German: k.u.k. Militärverwaltung in Serbien, Hungarian: k.u.k. Katonai igazgatás Szerbiában) was a military occupation of Serbia by the forces of the Austria-Hungary that took place during the First World War, starting officially on 1 January 1916.

Austro-Hungarian troops in the streets of Belgrade during the occupation of Serbia | |

| Date | 1 January 1916–1 November 1918 (2 years, 10 months, 4 weeks and 1 day) |

|---|---|

| Location | North West Serbia West of the Morava Valley |

Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on Serbia on 28 July 1914 marked the beginning of the First World War. After three unsuccessful Austro-Hungarian offensives between August and December 1914, a combined Austro-Hungarian and German offensive breached Serbian territory from the north and west in October 1915 while the Bulgarian army attacked from the south-east. By January 1916, all of Serbia was occupied by the Central Powers.

Serbia was divided into two separate occupation zones, Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian, both ruled by a military administration. The Austro-Hungarian occupation zone was limited to the northern three-quarters of Serbia, its military administration was set up with a governor and a civil commissioner at its head with the goal of denationalizing the Serb population. In addition to a severe military legal system, banning all political organizations, forbidding public assembly, and bringing schools under its control, a rigid economic system of exploitation was instituted. Uprisings were crushed with the harshest measures, including public hanging and shooting. During the occupation between 150,000 and 200,000 men, women, and children were deported to camps, built for that purpose in Austro-Hungarian territories, most notably Mauthausen in Austria, Auschwitz in Austrian Poland, and Györ in Hungary.[1]

The breakthrough of the Salonika front in October 1918 and the liberation of Belgrade on 1 November 1918 ended the occupation of the country.

Background

After the assassination of the Habsburg heir Franz Ferdinand by a Bosnian Serb student, the prestige of Austria-Hungary necessitated a punishing attack on the State that they deemed responsible. The Austrian military leadership was determined to destroy Serbian independence, which they saw as an unacceptable threat to the future of the empire and its large south Slav population. On 28 July 1914, one month after the murder of the Archduke and his wife, Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia, Habsburg batteries at Semlin on the Sava River immediately began hostilities by bombarding Belgrade, effectively beginning the First World War. Operations against Serbia were placed in the hands of Feldzeugmeister Oskar Potiorek, Governor-General of Bosnia-Hercegovina, on the morning of 12 August 1914 the first invasion of Serbia began.[2]

During the first punitive expedition of August 1914, Austro-Hungarian forces occupied Serbian territories for 13 days, that occupation turned into a brutal war of annihilation, accompanied by mass violence against civilians; during that period between 3,500 and 4,000 Serb civilians were killed in executions and random violence by marauding troops;[3] A second invasion in November captured Belgrade, Austro-Hungarian Croat General Stjepan Sarkotić was appointed Governor-General, concentration camps were set up and tens of thousands of Serbs interned.[3] By mid-December the Serbs managed, against all odds, to defeat the invaders at the battle of Kolubara and repel them out of the country. Humiliation at the hands of a small Balkan peasant kingdom badly wounded the pride and prestige of the dual monarchy and its military but although Austria-Hungary had failed to crush Serbia, the Serbs had exhausted their military abilities.[4] Germany urged Austria-Hungary to restore lost prestige by yet another offensive, but without Bulgarian participation in an offensive against Serbia, the Austro-Hungarian commander-in-chief would not consider it until almost a year later.

In September 1915 a secret pact was signed with Bulgaria, in October 1915 Serbia fell to a combined German, Austro-Hungarian, and Bulgarian invasion that started with the offensive of the Central Powers. The massive superiority in numbers and equipment, especially in artillery, of the invaders meant that the campaign was over within 6 weeks. The defeated Serbian army did not surrender but retreated across the mountains into exile with the government, the royal house and hundred of thousands of civilians. The Serb Army spent the rest of the war fighting against Bulgarian and German troops on the Salonika front. In the fall of 1915, Serbia was divided among the victors who each set up harsh occupational regimes.[5]

Administration and governance

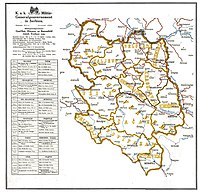

Shortly after the retreat of the Serbian army, the Austro-Hungarian occupation zone was divided into twelve, then thirteen approximately equal provinces (German: Kreise) which were then additionally divided into sixty-four districts (German: Brezirke).[6] The Austro-Hungarian administrative zone was limited to the region west of the Morava valley and to Macedonia; the areas east of the Morava, Macedonia itself and most of Kosovo fell under Bulgarian rule. A German occupation zone was established in the area east of Velika Morava, Južna Morava in Kosovo and the Vardar valley, the Germans took control of railways, mines and agricultural resources.[7]

On 1 January 1916 the Austro-Hungarian supreme command ordered the formation of a military governorate, the Militärverwaltung in Serbien (Military administration in Serbia) was established, with Belgrade as its administrative centre. The first Governor, Johann Graf Salis-Seewis, a Croat by ethnicity with experience of fighting insurgents in Macedonia, was appointed in late 1915 by the Emperor, he took office on 1 January 1916. A civilian commissar, Ludwig Thalloczy was appointed by the Hungarian government as his deputy, he arrived in Belgrade on 17 January 1916.[8] The occupation was subordinated to the Austro-Hungarian Armeeoberkommando (Army High Command or AOK), under Franz Conrad von Hoetzendorff and later Arthur Arz von Straußenburg.

During the occupation political expression in Serbia was severely limited with prohibition of newspaper publication (except MGG/S's Belgrader Nachrichten), prohibition of public assembly and political parties.[6] Large portion of Serbian political, intellectual and cultural elite left the country already during the Serbian army's retreat through Albania. MGG/S's policies aimed to depoliticize and denationalize population as both political and national agitation were perceived by the army to be the existential danger to the empire.[6] With that objective in mind MGG/S intended to ignore Hungarian objections and integrate Serbia as a part of the empire, but as an area which would remain under direct military rule for decades after the end of the World War I and an area in which political participation will be prohibited.[6]

System of occupation

The principal aim of the occupiers was the inauguration of a new legal system that would prevent guerilla resistance and exploit Serbia’s economic resources, for this the Austro-Hungarian control over the population was done in accordance with "Directives for the Political Administration in the Areas of the General Military Governorate in Serbia" (Direktiven für die politische Verwaltung im Bereiche des Militärgeneralgouvernements in Serbien) and "General Principles for the Imperial and Royal Military Administration in the Occupied Territories of Serbia" (Allgemeine Grundzüge für die K.u.K Militärverwaltung in den beset-zen Gebieten Serbiens).

Life under the occupation

Denationalization and depoliticization of the population

The policies of the Military Governorate of Serbia aimed to depoliticize and denationalize the Serb population since political and national awareness were perceived by the army to be the existential danger to the empire.[6] The Cyrillic alphabet was banned from schools and public spaces, streets were renamed, traditional Serbian clothing was banned and German became the official language, teachers were brought from Austria to teach in schools. Publishing houses and bookshops were closed down.

Political expression in Serbia was severely limited with the prohibition of newspaper publication, except the official Belgrader Nachrichten, public assembly and political parties, politician associations were disbanded, newspapers, books and mail were all tightly censored.[6]

Most of the Serbian political, intellectual and cultural elite had left the country following the great retreat, the remaining ones, including many university professors, teachers, and priest were arrested by the authorities and deported to camps in Austro-Hungarian territories.

Relations with the local population

The fear of a levée en masse captured the imagination of the army, causing it to engage in conflict with the population through hostage-taking, reprisals, and summary justice; military law was employed to overcome Serbian national resistance. If civilians were suspected to be engaging in resisting, they would face the harshest measures, including hanging and shooting. The house of the offending Serbian’s family would also be destroyed.[9]

According to Red Cross reports, starvation killed more than 8,000 Serbs that winter, at the same time figures from the Habsburg High Command reported that 170,000 cattle, 190,000 sheep, and 50,000 pigs had been exported to Austria-Hungary by mid-May 1917.[10] During the occupation, 150,000 to 200,000 Serbs were sent to camps in Austria-Hungary.[11]:75–6

The civilian population of Serbia under Austro-Hungarian occupation practiced passive resistance in refusing to salute occupiers and spreading rumors. Town officials and citizens were warned to not give or accept bribes. In Kruševac, the local military commander forbid any bribery, corruption, or defamation of "loyal citizens" in 1916. A message from the Austro-Hungarian intelligence service in Serbia concluded in early 1916 that:[11]:76–8

The peasants are obviously happy that they are spared from everything the war means. The intellectuals, in contrast, although currently peaceful because of fear, remain as they were i.e. every Serbian intellectual is half lawyer and half politician. He is a sworn enemy to any compatriot of a different political stamp, but united with all others in hating the winners.[11]:77

Former Prime Minister of Serbia Jovan Avakumović attempted to suggest to Governor General Johann Graf Salis-Seewis to issue a joint proclamation for the restoration of peace and order. Avakumović's suggestion was turned down, and his suggestion that he sign his name next to Salis-Seewis led to his arrest.[11]:78

Military commanders and governors

Military commanders

- Oskar Potiorek (28 August 1914 – 27 December 1914)

- Archduke Eugen Ferdinand (27 December 1914 – 27 May 1915)

- Karl Tersztyánszky von Nádas (27 May 1915 – 27 September 1915)

- Feldmarschal Hermann Kövess von Kövessháza (27 September 1915 – 1 January 1916)

Governors

- Feldmarschalleutnant Johan Ulrich Graf von Salis-Seewis (1 January 1916 – July 1916)

- Adolf Freiherr von Rhemen zu Barensfeld (July 1916 – October 1918)

- Feldmarschal Hermann Kövess von Kövessháza (October 1918 – 1 November 1918)

References

- Luthar 2016, p. 77.

- Schindler 2015, p. 177.

- Kramer 2008, p. 140.

- Pavlowitch 2002, p. 122.

- Calic & Geyer 2019, p. 166.

- Gumz 2014.

- Mitrović 2007, p. 183.

- Buttar 2016, p. 43.

- DiNardo 2015, p. 68.

- Calic & Geyer 2019, p. 157.

- Pintar, Olga Manojlović; Dodić, Vera Gudac (2016). “An Ugly Black Night”: Remembering the Austro-Hungarian Occupation of Serbia 1915–1918. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-31623-2.

Sources

- DiNardo, R.L. (2015). Invasion: The Conquest of Serbia, 1915. War, technology, and history. ABC-CLIO, LLC. ISBN 978-1-4408-0092-4.

- Fried, M. (2014). Austro-Hungarian War Aims in the Balkans during World War I. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-137-35901-8.

- Mitrović, A. (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914-1918. Central European studies. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-476-7.

- Calic, M.J.; Geyer, D. (2019). A History of Yugoslavia. Central European studies. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-838-3.

- Luthar, O. (2016). The Great War and Memory in Central and South-Eastern Europe. Balkan Studies Library. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31623-2.

- Gumz, J.E. (2014). The Resurrection and Collapse of Empire in Habsburg Serbia, 1914-1918: Volume 1. Cambridge Military Histories. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-68972-5.

- Buttar, P. (2016). Russia's Last Gasp: The Eastern Front 1916–17. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-1277-3.

- Kramer, A. (2008). Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War. Making of the Modern World. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-158011-6.

- Pavlowitch, S.K. (2002). Serbia: The History Behind the Name. Hurst & Company. ISBN 978-1-85065-477-3.

- Schindler, J.R. (2015). Fall of the Double Eagle: The Battle for Galicia and the Demise of Austria-Hungary. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-61234-806-3.