Georgian–Armenian War

The Georgian–Armenian War was a short border dispute fought in December 1918 between the newly independent Democratic Republic of Georgia and the First Republic of Armenia, largely over the control of former districts of Tiflis Governorate, in Borchaly (Lori) and Akhalkalaki.

| Georgian–Armenian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of World War I | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Drastamat Kanayan |

Giorgi Mazniashvili Giorgi Kvinitadze Valiko Jugheli | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

In Lori: initially 4,000 in total incl. partisans[2] or 28 infantry companies and 4 cavalry squadrons excl. partisans.[3] 6,500 troops at peak, supported by local rebels.[4] In Akhalkalaki: probably much fewer.[5][6] |

In Lori: several hundred initially incl. German troops.[7] Gradually increasing. More than 3,500 National Guard and People's Guard troops during the final stages of the war.[8][9] In Akhalkalaki: over 6,000.[5] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

hundreds killed, wounded or taken prisoner.[10][11] 1610 taken prisoner according to the government of Georgia[12] |

hundreds killed, wounded or taken prisoner.[10][11] About 1,000 taken prisoner according to Hovannisian[1] | ||||||||

| total death toll may range in the thousands[13] | |||||||||

In March 1918, Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and in doing so agreed to return to the Ottoman Empire territory gained during the 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War. These territories were, however, no longer under the functional control of the Russian central government; rather, they were being administered collectively by the Georgians, Armenians and Azerbaijanis through the Transcaucasian Sejm. The Trebizond Peace Conference aimed to resolve the dispute, but when the conference failed to produce a resolution, the Ottomans pursued a military campaign to control the disputed territories. Under persistent attack, the Transcaucasian collective eventually dissolved with the Georgians, Armenians and Azerbaijanis declaring independent nation states in quick succession in late-May 1918. On 4 June, the Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Batum with each of the three Transcaucasian states, which brought the conflict to an end and awarded the southern half of the ethnically-Armenian Lori Province and Akhalkalaki district to the Ottomans. Against the wishes of Armenia, Georgia, supported by German officers, took possession of northern Lori and established military outposts along the Dzoraget River.

When the Ottomans signed the Armistice of Mudros in October, they were subsequently required to withdraw from the region. Armenia quickly took control of territory previously controlled by the Ottomans, and skirmishes between Armenia and Georgia arose starting on 18 October. Open warfare began in early December, after diplomatic efforts failed to resolve the issue of the disputed border, and continued until 31 December, when a British-brokered ceasefire was signed, leaving the disputed territory under joint Georgian and Armenian administration.

Background

Russian revolution

After the February Revolution, the Russian Provisional Government installed the Special Transcaucasian Committee to govern the area.[14] However, following the October Revolution, the Special Transcaucasian Committee was replaced on 11 November 1917 by the Transcaucasian Commissariat centered in Tbilisi.[15] The Commissariat concluded the Armistice of Erzincan with the Ottoman Empire on 5 December 1917, ending localized armed conflict with the Ottoman Empire.[16] The Commissariat actively sought to suppress Bolshevik influence while concurrently pursuing a path towards Transcaucasian independence from Bolshevik Russia. This included establishing a legislative body, the Transcaucasian Sejm, to which the Commissariat surrendered its authority on 23 January 1918, following the dispersal of the Russian Constituent Assembly by the Bolsheviks.[15] The secessionist and anti-Bolshevik agenda eventfully brought Transcaucasian into conflict with the central government. On 3 March, the Russians signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk marking Russia's exit from World War I.[17] In the treaty, Russia agreed to return territory gained during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), giving little care to the fact that this territory was under the effective control of Armenian and Georgian forces.[17] The Trebizond Peace Conference, between the Ottoman Empire and the Sejm, began on 4 March and continued until April.[18] The Ottomans offered to surrender all the Empire's ambitions in the Caucasus in return for recognition of the re-acquisition of the east Anatolian provinces awarded at Brest-Litovsk.[19]

Independence

During the peace conference negotiations, the Ottoman representatives placed a great deal of pressure on the Transcaucasian delegation to declare independence, as they were only willing to sign a treaty with Transcaucasian if they were independent from Russia.[20] The Transcaucasian Sejm recalled its representatives on 31 March to discuss the Ottoman position.[20] On 5 April, the head of the Transcaucasian delegation Akaki Chkhenkeli accepted the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk as a basis for future negotiations.[21] The Sejm also declared formal independence from Soviet Russia by proclaiming the establishment of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic on 22 April.[20] Hostilities nevertheless resumed between the new republic and the Ottoman Empire, and by 25 April the Ottoman army had taken control of Kars and largely returned to its pre-war positions.[22] On 11 May, a new peace conference between the Republic and the Ottoman Empire began in Batumi. At the conference the Ottomans further extended their demands to include Tbilisi, Alexandropol and Echmiadzin.[23] The Ottoman army resumed hostilities on 21 May with the Battle of Sardarabad, Battle of Bash Abaran and Battle of Kara Killisse.

By this point, leading Georgian politicians viewed an alliance with Germany as the only way to prevent Georgia from being occupied by the Ottoman Empire.[24] Consequently, the Georgian National Council declared the independence of the Democratic Republic of Georgia on 24 May and two days later signed the Treaty of Poti with Germany, placing itself under German protection.[25][24] The following day, the Muslim National Council announced the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan.[26] Having been largely abandoned by its allies, the Armenian National Council declared its independence on May 28.[27] On 4 June, the Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Batum with each of the three Transcaucasus states, bringing the conflict with the Ottoman Empire to an end.[28] The treaty awarded the southern half of the ethnically-Armenia Lori Province and Akhalkalaki district to the Ottomans but did not firmly delineate the borders between the new Transcaucasus states.[29] In response, and to deny the Ottomans a direct route to Tbilisi, Georgian units supported by German officers took possession of northern Lori and established outposts along the Dzoraget River.[29]

Initial clashes

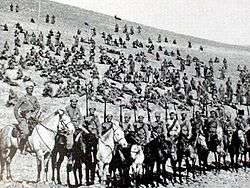

..jpg)

In early October 1918, the Ottomans pulled back from southern Lori, which eliminated the territorial buffer between Armenia and Georgia.[30] The Armenian military quickly filled the void by taking control of much of southern Lori on 18 October and in the absence of any resistance probed further north.[31] The first incident between Armenia and Georgia occurred the same day when an Armenian army detachment seized the railway station in the village of Kober near Tumanyan, refusing a subsequent demand from the Germans that they withdraw.[32][7] The local border guards called for help, and the Georgian government responded by sending two armoured trains and a detachment of 250 soldiers, which forced the Armenians to leave Kober.[7] Five days later, three Armenian companies attacked and overwhelmed a German garrison near the village of Karinj. Earlier, the Georgian government in Tbilisi had received a letter from Armenian Prime Minister Hovhannes Kajaznuni insisting that Georgia had no claims on the Lori district, and for the sake of avoiding a catastrophic crisis for both countries, Georgian troops should leave the region. Clashes intensified from 25–27 October, with neither side gaining the advantage, until the Georgians sent a company-sized force with an armoured train to support their German allies. Just a day later, the Georgian government received a telegram from Armenia explaining that the attacks were the result of a misunderstanding and proposed that a conference be convened to resolve the border issue.[33] On 27 October, Armenian troops left the two villages, they had occupied, and retreated south.[33]

Failed diplomatic attempts

The terms of the Armistice of Mudros between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies required the Ottomans pull their troops out of the Transcaucasus. The departure of the Ottomans created a power vacuum in the border area, in particular that between Armenia and Georgia. Armenia and Georgia began bilateral talks in November 1918, with Georgia sending a special envoy to Yerevan.[34] Simultaneously, Georgia invited the recently independent governments of the Caucasus to Tbilisi for a conference with the principal aim of addressing boundary delimitation and issues of common concern.[34] The general idea of a conference was well received by the Armenian government, however, the Armenia government took exception to the scope and quick timelines of the conference.[34] In particular, Armenia was not interested in discussing border issues at a conference.[34] Armenia indicated it would participate, recognizing the rapidly changing political environment following World War I, but reemphasized that they would not discuss the issues of delimitation.[34][35] In general, however, Georgia was of the position that the border with Armenia should be inline with the border of the former Russian imperial Tiflis Province; whereas, Armenia was of the position that the border should correspond to ethnic composition or more historical boundaries.[36]

The conference began in Tbilisi on 10 November with only the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus in attendance.[37] The Armenia delegation initially stated that they were unable to attend due to poor rail service between Yerevan and Tbilisi.[38] The Georgian delegation suggested that the conference start be postponed until 13 November to accommodate, but Armenia declined for several reasons, including the lack or readiness and clarity on several issues.[38] The Armenian delegation continued to postpone, and in order to accommodate the Armenians, Georgia first postponed the start of the conference to 20 November and then to 30 November.[38] After the final delay, the conference fell apart, and five days later, on 5 December, the Georgian mission headed by Simon Mdivani left Yerevan.[38] Georgia subsequently informed Armenia of its willingness to exclude the discussion of boundary disputes from a conference program but Armenia once again delayed a response, allegedly due to sabotage of telegraph lines.[38]

Prior to leaving Yerevan, the Mdivani mission did engage in talks with the Armenia government during which Armenia indicated a readiness to give up claims in Akhalkalaki and Borchalo if the Georgians would help them in either retaking Karabakh or assist with historical territorial claims within Western Armenia. The Georgian government, however, declined such offers, as they did not wish to become entangled in another conflict with the Ottoman army. Amidst failed negotiations, Georgia deployed troops in the villages near the border which only increased the tenseness of the situation.[39][40]

Open hostilities

Armenian offensive

In early December 1918, the Georgians were confronted with regional rebellion in the Lori area, chiefly in the village of Uzunlar.[41] The local garrison in the village of Uzunlar was attacked by disgruntled local villagers, resulting in one Georgian soldier being killed and the remaining soldiers being disarmed and taken prisoner.[7] The Georgians argued that Armenian soldiers from the 4th Infantry Regiment had disguised themselves as bandits and were fomenting rebellion; whereas, Armenia took the position that the events were the result of Georgia's oppressive behavior towards the local ethnic-Armenian population.[42] In response, General Varden Tsulukidze sent a 200-soldier detachment to the area to quell the unrest.[43] The detachment was, however, unable to provide any relief, as they were driven back by heavy gunfire.[42]

Borchali/Lori district

Still not realising the actual scale of the threat he was facing, Tsulukidze's headquarters in Sanahin was quickly approached and besieged by regular Armenian army units resulting in heavy fighting around the railway station. The Armenians sabotaged rails and also succeeded in ambushing and trapping an armoured train that was carrying two Georgian infantry companies. Tsulukidze withdrew from Sanahin to Alaverdi — which was also being attacked by Armenian forces, using the artillery of the derailed trains to cover his troops' retreat. More Georgian reinforcements arrived on December 12, securing the heights around Alaverdi, but were unsuccessful in breaking out the ~60 Georgians who remained trapped on the rails between the two villages. Another train with reinforcements got derailed on the same day. At that point, the Georgians had less than 700 troops engaged in combat, while most of them took defensive positions in Alaverdi, equipped with a few guns and mortars. On December 14, they were encircled by an estimated 4,000 Armenian soldiers from regiments of the 1st and 2nd Rifle Divisions. Confronted with a hopeless situation, General Tsulukidze ordered a general retreat and made a successful breakout towards Sadakhlo.

Simultaneously, from 12 to 14 December, Georgian forces under General Tsitsianov were struck by Armenian troops around the villages of Vorontsovka and Privolnoye. On 12 December, the National Guard detachment that was guarding Vorontsovka was called back to Tbilisi to participate in a military parade marking the 1st anniversary of the National Guard of Georgia. Tsitsianov's few hundred men, although heavily outnumbered, offered brutal resistance with their artillery, using shrapnel ammunition at point-blank range. The Armenians eventually managed to take both towns. The Georgian forces, having suffered more than 100 killed by that point, and some material, retreated towards Katharinenfeld. On December 14, the Armenians, who had already amassed more than 6,500 regular troops supported by thousands of armed local militia, steamrolled what resistance remained in the Alexandrovka-Vorontsovka-Privolnoye triangle. By the end of the second day of that attack, the Armenian army had captured almost all of the contested villages. Sanahin and Alaverdi also fell. Georgian defenders and refugees started to evacuate the area by train on December 17. The Georgians sustained heavy losses, leaving behind hundreds of prisoners, one train and both derailed armoured trains. The Armenian army's left flank, commanded by colonels Nikogosov and Korolkov, performed decisive flanking manoeuvers that surprised and encircled the Georgians in Ayrum and culminated in the capture of the town on December 18. Despite a successful breakout, the Georgian 5th and 6th Infantry Regiments lost around 560 men killed, wounded or taken prisoner, and about 25 machine guns and two cannons in total.

On the same day, the Armenian vanguard pushed against Sadakhlo, where Tsulukdize's forces had fortified themselves at the station and nearby strategic heights. The initial Armenian attack was repulsed, and in order to outflank the defenders, the town of Shulaveri was captured the next day. Korolkov called for all Armenian men in the area able to fight to mobilize and support the army's offensive. On 20 December, the Armenians were blockading a vital train station that connected Sadakhlo with Tbilisi, preventing further reinforcements. A day after, they massed their artillery and launched an attack on the town, only to be repulsed with heavy casualties by the defenders, who were equipped with an armoured train. Using the same train, the remaining Georgian troops broke out of the encirclement to join a defensive line further north. Following that defeat, Tsulukidze resigned and was replaced by General Sumbatashvili. The Georgian army was already mobilizing in the Lori district and started to prepare for major counterattacks.[44][45][46]

Akhalkalaki district

Less significant were the clashes in the Akhalkalaki district. The Armenian operation was thwarted by the massive Georgian military presence and lack of support by the local Armenian population. The region was garrisoned with over 6,000 troops commanded by general Abel Makashvili.[5][47] Despite the odds, Armenian forces mounted an offensive, seizing four villages. Makashvili demanded they leave the area immediately otherwise punitive actions would take place. On 14 December the Armenians met the demand and left the villages, only to renew their attacks a few days later, this time around with cavalry support. The village of Troitskoe changed hands several times until the Georgians ultimately retook it and repelled all Armenian units from the area.[5][48] On 19 December Armenian forces once again attempted to take Troitskoe but were repulsed, losing 100 men to Georgian machine gun fire.[5] Due to heavy winter storms, neither side could achieve any military breakthrough in the region. Confrontations in the Akhalkalaki district ceased for the rest of the war while all Georgian troops there had to remain, on the order of high command, despite the critical situation in Lori.[5]

Georgian counterattack and end of hostilities

Battles at Katharinenfeld and Shulaveri

Katharinenfeld

The Armenian army kept advancing and occupied most Armenian dominated villages in the Lori/Borchali province, then proceeded to enter the town Bolnisi-Knachen near heavily fought Katharinenfeld and rested only a few dozen kilometers away from the Georgian capital. Even though attacking Tbilisi was not a primary goal for the Armenians it was an alarming immediate threat to the Georgian government. The mobilization order was not issued earlier than December 18 and approved only 2 days later. Commander Jugheli was put in charge of the ill-disciplined Georgian National Guard troops in Katharinenfeld while general Akhmetashvili was appointed commander in chief of the Georgian army forces in the Lori theatre. Jugheli's 600 men encamped in a poorly and carelessly organised position without even posting guards allowing Armenian militia to sneak up on them overnight and capture several cannons and machineguns and position themselves on the roofs to surprise the Georgians. However, despite the momentum the Armenians had gained, the Georgians with Jugheli leading them while under attack managed to recapture the equipment in close combat and forced the Armenians out of town, but with heavy casualties, losing 30 killed and 70 wounded. The Armenians also suffered heavy losses during retreat with 100 killed and 100 taken prisoner when they were run down by Georgian cavalry led by Colonel Cholokashvili. Georgian troops crossed the river Khrami with the first main objective to crush the Armenian force in the Dagheti-Samshvilde area. The Armenian troops including 500 well-entrenched militia were engaged by Georgian artillery and on 24 December the villages Dagheti, Bolnisi, Khacheni and Samshvilde were captured by the Georgian army eliminating most of the resistance in the process.[49]

Recapture of Shulaveri and stalemate

With the expulsion of Georgian troops under Tsulukidze from Sadakhlo the Armenians were effectively controlling most of the contested areas within the Borchali/Lori district, except Katharinenfeld which the Georgians had retaken. Following the demand of general Dro, who directly threatened an attack beyond the Khram and indirectly an attack on Tbilisi if the Georgians didn't concede and officially transfer the Akhalkalaki district to Armenia,[50] the Georgians quickly switched from a defensive posture to offensive operations. The Georgian government appointed their most respected military leader general Mazniashvili commander in charge of the planned Shulaveri operation while being supported by generals Kvinitadze and Sumbatashvili.[50][51] On December 24 the Armenians defending the railway station Ashaga-Seral were surprised and overwhelmed by a Georgian cavalry charge supported by artillery fire from an armoured train. Just hours later Georgian infantry entered several villages and Little Sulaveri and secured a railway bridge while a single battalion cleared the strategic mountain between Ashaga and Shulaveri.[50] Those actions allowed the general staff to move closer to the frontline at the station. General Dro's forces maintained the initiative as they had the superior numbers and positions while the Georgians were still amassing sufficient force to mount decisive attacks. Instead Mazniashvili resorted to deep outflanking manoeuvers by single local infantry and cavalry detachments to prevent a coordinated Armenian advance while the main army was still assembling.[52] If the Armenians had launched an attack before the Georgian army arrived in full force, nothing would have prevented them from taking Tbilisi. Mazniashvili's plan was to distract with diversionary flanking manoeuvers that threatened Shulaveri and the strategically important railway connection. The Armenian commanders responded by deploying and concentrating the bulk of their army in and around Shulaveri taking up defensive positions and mobilising all available forces to oppose a potential Georgian assault on the town. Mazniashvili had succeeded with his plan. He focused what available troops he had at hand, around 1000 men, for several simultaneous attacks on the flanks seizing a number of villages around Shulaveri on December 25. To the north of Shulaveri a Georgian National Guard battalion secured a mountain directly facing the town providing a decisive strategic stronghold that oversaw most of the area. An Attack on Shulaveri itself followed almost instantly carried out by artillery and two Georgian aircraft which dropped bombs on the Armenian positions.[52][51] The general assault was scheduled for the next day on December 26. However the battalion that was supposed to guard the mountain, left it to resupply and rest as its soldiers felt uncomfortable to rest on the mountain itself. As a result, the Armenians retook it, only to be repulsed on the same day. Paradoxically exactly the same event occurred shortly after. The Georgians once again left the mountain for the same reason losing it a third time. The commander in charge of the battalion resigned due to the behaviour of his men. As a consequence the operation was postponed until December 27. Mazniashvili attempted to take Shulaveri with a frontal attack personally leading the assault but was repelled by the Armenian defenders.[53] A day later the Armenians got reinforced by another regiment and the Georgian army followed by a 2-hour artillery barrage renewed its offensive with around 3,500 men and was able to seize the strategic heights east of the town which put them in an advantageous position. Shulaveri was retaken by nightfall on the same day while the Georgian general staff entered the town on December 29. Suffering almost 200 killed and many wounded the Armenian army split in two groups and retreated.[8][9] One of the groups heading towards Sadakhlo along the railway line was intercepted and scattered by Georgian cavalry. The other group fell back to the village of Sioni. 24 hours later on 30 December the Georgians seized Sadakhlo after it changed hands several times and the village Lamballo.[8][9] Unaware and not timely informed by the government of a scheduled ceasefire that would begin on 1 January 1919, Mazniashvili had planned another major offensive but not earlier than January 1. The Armenians on the other hand were informed and had already prepared to retake Sadhaklo and Lamballo on December 31 and got reinforced for that operation. In the subsequent fighting on 31 December neither side achieved its goals. The Armenians were able to take Lamballo once again but failed to take Sadakhlo entrenching themselves at the nearby railway station while the Georgians kept hold of the town itself.[1] The Georgians on the other side were not able to retake Lamballo after several attempts even when reinforced. Both armies rested on irregular lines.[1] On 1 January 1919 hostilities ceased and the two nations' army commanders held peace talks which continued in Tbilisi. The conflict was officially ended on January 9 with the involvement of a British special envoy.

Aftermath

Both parties signed a peace agreement in January 1919 brokered by the British. Armenian and Georgian troops left the territory and both sides agreed to begin talks on designating a neutral zone. The neutral zone later was divided between the Armenian SSR and Georgian SSR.

Footnotes

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 119.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 27.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 111.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 29.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 28.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 125.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 18.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 44.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 118.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, pp. 26-45.

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 111-119.

- სომეხი ტყვეები 1918 წლის ომის დროს 2016, p. 1.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 48.

- Mikaberidze 2015, p. 612-613.

- Mikaberidze 2015, p. 32.

- Swietochowski 1985, p. 119.

- Smele 2015, pp. 226-227.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 23.

- Shaw 1977, p. 326.

- Hille 2010, p. 76.

- Hovannisian 1997, pp. 292–293.

- Macfie 2014, p. 154.

- Payaslian 2008, p. 150.

- Hille 2010, p. 71.

- Lang 1962, pp. 207-208.

- Hille 2010, p. 177.

- Hovannisian 1997, pp. 186-201.

- Payaslian 2008, p. 152.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 71.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 73.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 73-75.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 75.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 20.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 23.

- Walker 1980, pp. 267-268.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 17.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 97.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 24.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 103.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 25.

- The village is currently named Odzun but was named Uzunlar until 1967.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 104.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 26.

- Armeno-Georgian War of 1918 and Armeno-Georgian Territorial Issue in the 20th Century, Andrew Anderson

- The Republic of Armenia Volume I: 1918-1919, Richard G. Hovannisian

- INDEPENDENT GEORGIA (1918-1921), David Marshall Lang

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 101.

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 102.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 39.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 40.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 114.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 42.

- Andersen & Partskhaladze 2015, p. 43.

Bibliography

- Andersen, Andrew; Partskhaladze, George (2015). Armeno-Georgian War of 1918 and Armeno-Georgian Territorial Issue in the 20th Century. academia.edu.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hovannisian, Richard (1971). The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918-1919. Volume I. Berkeley: University of California Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hille, Charlotte Mathilde Louise (2010), State Building and Conflict Resolution in the Caucasus, Eurasian Studies Library, BRILLCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hovannisian, Richard (1997), The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times: Foreign Domination to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, Volume II, ISBN 978-0-333-61974-2, OCLC 312951712CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lang, David Marshall (1962), A Modern History of Georgia, London: Weidenfeld and NicolsonCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Macfie, Alexander Lyon (2014), The End of the Ottoman Empire, 1908-1923, RoutledgeCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015), Historical Dictionary of Georgia, Rowman & LittlefieldCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Payaslian, S. (2008), The History of Armenia, SpringerCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977), Reform, revolution and republic : the rise of modern Turkey (1808-1975), History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, 2, Cambridge University Press, OCLC 78646544CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smele, Jonathan (2015), Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916-1926, Rowman & LittlefieldCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1985), Russian Azerbaijan, 1905-1920: The Shaping of a National Identity in a Muslim Community, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-26310-8CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- სომეხი ტყვეები 1918 წლის ომის დროს, legionerebi, 2016CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, Christopher (1980). Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)