Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War[N 1] (14 February 1919 – 18 October 1920) was fought by the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Russia over a region comparable to today's westernmost Ukraine and parts of modern Belarus. Russia sought to cross Poland in order to stimulate a Europe-wide communist revolution under the Trotskyist slogan "to give water to red horses out of the Wisła (Vistula) and Rhine".[11]

| Polish–Soviet War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Aftermath of World War I as well as the spillover of the Southern Front of the Russian Civil War and Lithuanian Wars of Independence during the Interwar period | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Logistical support:

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Early 1919: ~50,000[1] Summer 1920: 800,000–950,000[2] |

Early 1919: ~70,000[3] Summer 1920: 738,000–1,000,000[4] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Estimated 67,000-70,000 killed[5] 80,000–157,000 taken prisoner[6][7] (including rear-area personnel) |

About 47,000 killed[8][9][10] 113,518 wounded[9] 51,351 taken prisoner[9] | ||||||||

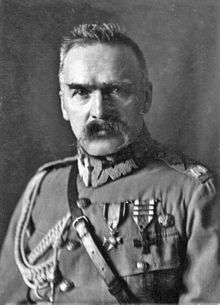

Poland's Chief of State, Józef Piłsudski, felt the time was right to expand Polish borders as far east as feasible, to be followed by a Polish-led Intermarium federation of Central and Eastern European states, as a bulwark against the re-emergence of German and Russian imperialism. Vladimir Lenin saw Poland as the bridge the Red Army had to cross to assist other Communist movements and bring about more European revolutions. By 1919, Polish forces had taken control of much of Western Ukraine, emerging victorious from the Polish–Ukrainian War. The West Ukrainian People's Republic, led by Yevhen Petrushevych, had tried to create a Ukrainian state on territories to which both Poles and Ukrainians laid claim. In the Russian part of Ukraine Symon Petliura tried to defend and strengthen the Ukrainian People's Republic but as the Bolsheviks began to win the Russian Civil War, they started to advance westward towards the disputed Ukrainian territories, causing Petliura's forces to retreat to Podolia. By the end of 1919, a clear front had formed as Petliura decided to ally with Piłsudski. Border skirmishes escalated following Piłsudski's Kiev Offensive in April 1920.

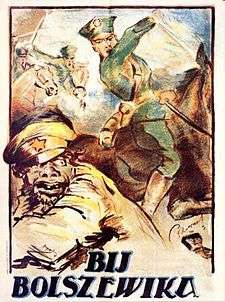

The Polish offensive was met by a successful Red Army counter-attack. On 9 May 1920, the Soviet newspaper Pravda printed its article "Go West!" (Russian: На Запад!, Na Zapad!), stating: "Through the corpse of the White Poland lies the way to World Inferno. On bayonets we will carry happiness and peace to working humanity".[12] The Soviet operation pushed the Polish forces back westward all the way to the Polish capital, Warsaw, while the Directorate of Ukraine fled to Western Europe. Western fears of Soviet troops arriving at the German frontiers increased the interest of Western powers in the war. In mid-summer, the fall of Warsaw seemed certain but in mid-August, the tide had turned again, as the Polish forces achieved an unexpected and decisive victory at the Battle of Warsaw. In the wake of the Polish advance eastward, the Soviets sued for peace and the war ended with a cease-fire on 18 October 1920.

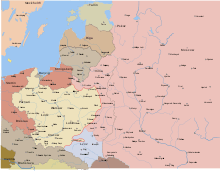

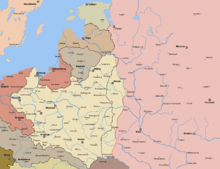

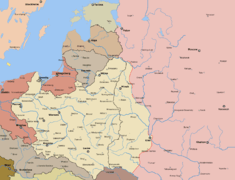

The Peace of Riga was signed on 18 March 1921, dividing the disputed territories between Poland and Soviet Russia. The war largely determined the Soviet–Polish border for the Interbellum. Poland gained a territory of around 200 kilometers east of its former border, the Curzon Line, which had been defined by an international commission after World War I.[13]

Names and dates

The war is known by several names. "Polish–Soviet War" is the most common but other names include "Russo–Polish War [or Polish–Russian War] of 1919–1921"[N 2] (to distinguish it from earlier Polish–Russian wars) and "Polish–Bolshevik War".[14] This second term (or just "Bolshevik War" (Polish: Wojna bolszewicka)) is most common in Polish sources. In some Polish sources it is also referred as the "War of 1920" (Polish: Wojna 1920 roku).[N 3]

There is disagreement over the dates of the war. The Encyclopædia Britannica begins its article with the date range 1919–1920 but then states, "Although there had been hostilities between the two countries during 1919, the conflict began when the Polish head of state Józef Pilsudski formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlyura (21 April 1920) and their combined forces began to overrun Ukraine, occupying Kiev on 7 May."[N 2] The Polish encyclopaedia Internetowa encyklopedia PWN,[14] as well as Western historians such as Norman Davies, consider 1919 the starting year of the war.[15]

The ending date is given as either 1920 or 1921; this confusion stems from the fact that while the cease-fire was put into force on 18 October 1920, the official treaty ending the war was signed months later, on 18 March 1921. While the events of 1919 can be described as a border conflict, and only in early 1920 did both sides engage in all-out war, the conflicts that took place in 1920 were an inevitable escalation of fighting that began in earnest a year earlier. In the end, the events of 1920 were a logical, though unforeseen, consequence of the 1919 prelude.[15]

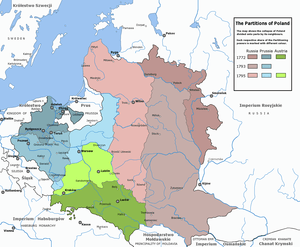

Prelude

The war's main territories of contention lie in present-day Ukraine and Belarus; until the middle of the 13th century they formed part of the medieval state of Kievan Rus'. After a period of internecine wars and the Mongolian invasion of 1240, these lands became objects of expansion for the Kingdom of Poland and for the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the first half of the 14th century, the Grand Duchy of Kiev and land between the Dnieper, Pripyat, and Daugava (Western Dvina) rivers became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and in 1352 Poland and Lithuania divided the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia between themselves. In 1569, in accordance with the terms of the Union of Lublin between Poland and Lithuania, some of the Ukrainian lands passed to the Polish Crown. Between 1772 and 1795, much of the Eastern Slavic territories became part of the Russian Empire in the course of the Partitions of Poland. After the Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815, much of the territory of the Duchy of Warsaw (Poland) transferred into Russian control.[16] After young Poles refused to be conscripted into the Imperial Russian Army during the uprising in Poland in 1863, Tsar Alexander II stripped Poland of its separate constitution, forced Russian to be the only language spoken, took away vast tracts of land from Poles, and incorporated Poland directly into Russia by dividing it into ten provinces, each with an appointed Russian military governor and all under complete control of the Russian Governor-General at Warsaw.[17][18]

As World War I ended (1918), the map of Central and Eastern Europe changed drastically.[19] Germany's defeat rendered Berlin's plans for the creation of Eastern European puppet states (Mitteleuropa), including one in Poland, obsolete.[20] The Russian Empire collapsed, resulting in the 1917 Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War[21] of 1917–1922. Several small nations of the region saw a chance for real independence and seized the opportunity to gain it;[19] Soviet Russia viewed its lost territories as rebellious provinces, vital for its security,[22] but did not have the resources to react swiftly.[21] While the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 had not made a definitive ruling in regard to Poland's eastern border, it issued a provisional boundary in December 1919 (the Curzon line) as an attempt to define the territories that had an "indisputably Polish ethnic majority"; the conference participants did not feel competent to make a certain judgment on the competing claims.[23]

With the success of the Greater Poland Uprising (1918–1919), Poland had re-established its statehood for the first time since the 1795 partition. Forming the Second Polish Republic, it proceeded to carve out its borders from the territories of its former partitioners. Many of these territories had long been the object of conflict between Russia and Poland.

Poland was not alone in its new-found opportunities and troubles. With the collapse of Russian and German occupying authorities, virtually all of Poland's newly independent neighbours began fighting over borders: Romania fought with Hungary over Transylvania, Yugoslavia with Italy over Rijeka, Poland with Czechoslovakia over Cieszyn Silesia, with Germany over Poznań and with Ukrainians over Eastern Galicia. Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians fought against each other and against the Russians, who were just as divided.[24] Spreading Communist influences resulted in Communist revolutions in Munich (April–May 1919), in Berlin (January 1919), in Budapest (March–August 1919) and in Prešov in Slovakia (June–July 1919). Winston Churchill commented sarcastically: "The war of giants has ended, the wars of the pygmies begin."[25] All of these engagements–with the sole exception of the Polish–Soviet war–would prove short-lived.

The Polish–Soviet war likely happened more by accident than design, as it seems unlikely that anyone in Soviet Russia or in the new Second Republic of Poland would have deliberately planned a major foreign war.[15][26] Poland, its territory a major battle-ground during World War I, lacked political stability; it had won the difficult conflict with the West Ukrainian National Republic by July 1919 but had already become embroiled in new conflicts with Germany (the Silesian uprisings of 1919 to 1921) and with Czechoslovakia (January 1919). Revolutionary Russia, meanwhile, focused on thwarting counter-revolution and the intervention by the Allied powers (1918 to 1925). While the first clashes between Polish and Soviet forces occurred in February 1919, it would take almost a year before both sides realised that they had become engaged in a full-scale war.[15]

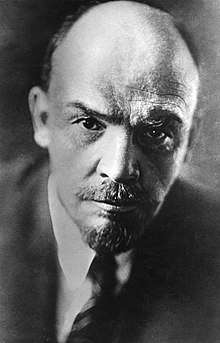

As early as late 1919 the leader of Russia's new Bolshevik Government, Vladimir Lenin, inspired by the Red Army's civil-war victories over White Russian anti-Communist forces and their Western allies, began to see the future of the revolution with greater optimism. The Bolsheviks proclaimed the need for the dictatorship of the proletariat, and agitated for a worldwide Communist community. They had an avowed intent to link the revolution in Russia with an expected revolution in Germany and to assist other Communist movements in Western Europe; Poland was the geographical bridge that the Red Army would have to cross to provide direct physical support in the West.[22][27][28][29] Lenin aimed to regain control of the territories abandoned by Russia in the Brest-Litovsk Treaty of March 1918, to infiltrate the borderlands, to set up Soviet governments there as well as in Poland, and to reach Germany – where he expected a Socialist revolution to break out.[22] He believed that Soviet Russia could not survive without the support of a socialist Germany.[22] By the end of the summer of 1919 the Soviets had taken over most of Ukraine, driving the Ukrainian Directorate from Kiev. In February 1919 they also set up a Lithuanian–Belorussian Republic (Litbel). This government was very unpopular due to terror and the collection of food and goods for the army.[22]

Officially, however, the Soviet Government denied charges of trying to invade Europe.[30]

As Polish-Soviet fighting progressed, particularly around the time Poland's Kiev Offensive had been repelled in June 1920, the Soviet policy-makers, including Lenin, increasingly saw the war as a real opportunity to spread the revolution westwards.[22][28][31] Historian Richard Pipes noted that before the Kiev Offensive, the Soviets had prepared for their own strike against Poland.[28]

Before the start of the Polish–Soviet War, Polish politics were strongly influenced by Chief of State (naczelnik państwa) Józef Piłsudski.[32] Piłsudski wanted to break up the Russian Empire[33] and to set up a Polish-led[34][35][36][37][38] "Międzymorze Federation" of independent[38] states: Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, and other Central and East European countries emerging out of crumbling empires after the First World War.[39] He hoped that this new union would become a confederation[40] and a counter-weight to any potential imperialist intentions on the part of Russia or of Germany. Piłsudski argued "There can be no independent Poland without an independent Ukraine", but he may have been more interested in Ukraine being split from Russia than in Ukrainians' welfare.[41][42] He did not hesitate to use military force to expand the Polish borders to Galicia and Volhynia, crushing a Ukrainian attempt at self-determination in the disputed territories east of the Southern Bug River, which contained a significant Polish minority,[22] who made up the majority of the population in cities like Lwów, in contrast to the Ukrainian majority in the countryside. Speaking of Poland's future frontiers, Piłsudski said: "All that we can gain in the west depends on the Entente – on the extent to which it may wish to squeeze Germany," while in the east, "There are doors that open and close, and it depends on who forces them open and how far."[43] In the chaos to the east the Polish forces set out to expand there as much as feasible. On the other hand, Poland had no intention of joining the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War[22] or of conquering Russia itself.[44]

Piłsudski also said:

Closed within the boundaries of the 16th century, cut off from the Black Sea and Baltic Sea, deprived of land and mineral wealth of the South and South-east, Russia could easily move into the status of second-grade power. Poland as the largest and strongest of new states, could easily establish a sphere of influence stretching from Finland to the Caucasus.[45]

Before the Polish–Soviet war, Jan Kowalewski, a polyglot and amateur cryptologist, managed to break the codes and ciphers of the army of the West Ukrainian People's Republic and of General Anton Denikin's White Russian forces during his service in the Polish–Ukrainian War. As a result, in July 1919 he was transferred to Warsaw, where he became chief of the Polish General Staff's radio-intelligence department. By early September he had gathered a group of mathematicians from Warsaw University and Lwów University (most notably, founders of the Polish School of Mathematics – Stanisław Leśniewski, Stefan Mazurkiewicz and Wacław Sierpiński), who succeeded in breaking Soviet Russian ciphers as well. Decoded information presented to Piłsudski showed that Soviet peace proposals with Poland in 1919 were false and that in reality the Soviets had prepared for a new offensive against Poland and had concentrated military forces in Barysaw near the Polish border. Piłsudski decided to ignore the Soviet proposals, to sign an alliance with Symon Petliura of the Ukrainian People's Republic, and to prepare the Kiev Offensive. During the war, Polish decryption of Red Army radio messages made it possible to use small Polish military forces efficiently against the Soviet Russian forces and to win many individual battles, most importantly the 1920 Battle of Warsaw.[46][47][48]

Course

.png)

1919

First Polish–Soviet conflicts

The first serious armed conflict of the war took place around 14 February[15][26] – 16 February, near the towns of Manevychi and Biaroza in Belarus.[14][22] By late February the Soviet westward advance had come to a halt. Both Polish and Soviet forces had also been engaging the Ukrainian forces, and active fighting was going on in the territories of the Baltic countries (cf. Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Wars of Independence).

In early March 1919, Polish units started an offensive, crossing the Neman River, taking Pinsk, and reaching the outskirts of Lida. Both the Soviet and Polish advances began around the same time in April (Polish forces started a major offensive on 16 April[14]), resulting in increasing numbers of troops arriving in the area. That month the Red Army had captured Grodno, but was soon pushed out by a Polish counter-offensive. Unable to accomplish its objectives and facing strengthening offensives from the White forces, the Red Army withdrew from its positions and reorganised. Polish forces continued a steady eastern advance.[14] They took Lida on 17 April[14] and Nowogródek on 18 April, and recaptured Vilnius on 19 April, driving the Litbel Government from their proclaimed capital.[22] On 8 August, Polish forces took Minsk[14] and on 28 August they deployed tanks for the first time. After heavy fighting, the town of Babruysk near the Berezina River was captured.[14] By 2 October, Polish forces reached the Daugava river and secured the region from Desna to Daugavpils (Dyneburg).[14]

Polish success continued until early 1920.[14] Sporadic battles erupted between Polish forces and the Red Army, but the latter was pre-occupied with the White counter-revolutionary forces and was steadily retreating on the entire western frontline, from Latvia in the north to Ukraine in the south. In early summer 1919, the White movement had gained the initiative, and its forces under the command of Anton Denikin were marching on Moscow. Piłsudski was aware that the Soviets were not friends of independent Poland, and considered war with Soviet Russia inevitable.[49] He viewed their westward advance as a major issue, but also thought that he could get a better deal for Poland from the Bolsheviks than their Russian civil war contenders,[50] as the White Russians – representatives of the old Russian Empire, partitioner of Poland – were willing to accept only limited independence of Poland, likely in the borders similar to that of Congress Poland, and clearly objected to Ukrainian independence, crucial for Piłsudski's Międzymorze,[51] while the Bolsheviks did proclaim the partitions null and void.[52] Piłsudski thus speculated that Poland would be better off with the Bolsheviks, alienated from the Western powers, than with the restored Russian Empire.[50][53] By his refusal to join the attack on Lenin's struggling government, ignoring the strong pressure from the Entente, Piłsudski had possibly saved the Bolshevik Government in summer–fall 1919,[54] although a full-scale attack by the Poles in support of Denikin was not possible.[55] He later wrote that in case of a White victory, in the east Poland could only gain the "ethnic border" at best (the Curzon line). At the same time, Lenin offered Poles the territories of Minsk, Zhytomyr, Khmelnytskyi, in what was described as mini "Brest"; Polish military leader Kazimierz Sosnkowski wrote that the territorial proposals of the Bolsheviks were much better than what the Poles had wanted to achieve.

Diplomatic front, part 1

In 1919, several unsuccessful attempts at peace negotiations were made by various Polish and Russian factions.[14] In the meantime, Polish–Lithuanian relations worsened as Polish politicians found it hard to accept the Lithuanians' demands for certain territories, especially the city of Vilnius which had a Polish ethnic majority but was regarded by Lithuanians as their historical capital.[56] Polish negotiators made better progress with the Latvian Provisional Government, and in late 1919 and early 1920 Polish and Latvian forces were conducting joint operations including the Battle of Daugavpils, against Soviet Russia.[57]

The Warsaw Treaty, an agreement with the exiled Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlura signed on 21 April 1920, was the main Polish diplomatic success. Petlura, who formally represented the Government of the Ukrainian People's Republic (by then de facto defeated by Bolsheviks), along with some Ukrainian forces, fled to Poland, where he found asylum. His control extended only to a sliver of land near the Polish border.[58] In such conditions, there was little difficulty convincing Petlura to join an alliance with Poland, despite recent conflict between the two nations that had been settled in favour of Poland.[59] By concluding an agreement with Piłsudski, Petlura accepted the Polish territorial gains in Western Ukraine and the future Polish–Ukrainian border along the Zbruch River. In exchange, he was promised independence for Ukraine and Polish military assistance in reinstalling his government in Kiev.[22]

For Piłsudski, this alliance gave his campaign for the Międzymorze federation the legitimacy of joint international effort, secured part of the Polish eastward border, and laid a foundation for a Polish-dominated Ukrainian state between Russia and Poland.[59] For Petlura, this was the final chance to preserve the statehood and, at least, the theoretical independence of the Ukrainian heartlands, even while accepting the loss of West Ukrainian lands to Poland. Yet both of them were opposed at home. Piłsudski faced stiff opposition from Dmowski's National Democrats who opposed Ukrainian independence. Petlura, in turn, was criticised by many Ukrainian politicians for entering a pact with the Poles and giving up on Western Ukraine.[31][60][61]

The alliance with Petlura did result in 15,000 pro-Polish allied Ukrainian troops at the beginning of the campaign,[62] increasing to 35,000 through recruitment and desertion from the Soviet side during the war.[62] This would, in the end, provide insufficient support for the alliance's aspirations.

1920

Opposing forces

Norman Davies notes that estimating strength of the opposing sides is difficult – even generals often had incomplete reports of their own forces.[63]

Red Army

By early 1920, the Red Army had been very successful against the White armies.[38] They defeated Denikin and signed peace treaties with Latvia and Estonia. The Polish front became their most important war theater and a plurality of Soviet resources and forces were diverted to it. In January 1920, the Red Army began concentrating a 700,000-strong force near the Berezina River and in Belarus.[26]

By the time the Poles launched their Kiev offensive, the Red South-western Front had about 82,847 soldiers, including 28,568 front-line troops. The Poles had some numerical superiority, estimated from 12,000 to 52,000 personnel.[63] By the time of the Soviet counter-offensive in mid-1920 the situation had been reversed: the Soviets numbered about 790,000 – at least 50,000 more than the Poles; Tukhachevsky estimated that he had 160,000 "combat ready" soldiers; Piłsudski estimated his enemy's forces at 200,000–220,000.[64]

During 1920, Red Army personnel numbered 402,000 at the Western front and 355,000[2] for the South-west Front in Galicia. Grigoriy Krivosheev gives similar numbers, with 382,071 personnel for the Western Front and 282,507 personnel for the South-western Front between July and August.[65]

Norman Davies shows the growth of Red Army forces on the Polish front in early 1920:[66]

- 1 January 1920 – 4 infantry divisions, 1 cavalry brigade

- 1 February 1920 – 5 infantry divisions, 5 cavalry brigades

- 1 March 1920 – 8 infantry divisions, 4 cavalry brigades

- 1 April 1920 – 14 infantry divisions, 3 cavalry brigades

- 15 April 1920 – 16 infantry divisions, 3 cavalry brigades

- 25 April 1920 – 20 infantry divisions, 5 cavalry brigades

Among the commanders leading the Red Army in the coming offensive were Leon Trotsky, Tukhachevsky (new commander of the Western Front), Alexander Yegorov (new commander of the South-western Front) and the future Soviet ruler Joseph Stalin.

Polish forces

The Polish Army was made up of soldiers who had formerly served in the various partitioning empires, supported by some international volunteers, such as the Kościuszko Squadron.[67] Boris Savinkov was at the head of an army of 20,000 to 30,000 largely Russian POWs, and was accompanied by Dmitry Merezhkovsky and Zinaida Gippius. The Polish forces grew from approximately 100,000 in 1918 to over 500,000 in early 1920.[68] In August 1920, the Polish Army had reached a total strength of 737,767 soldiers; half of that was on the frontline. Given Soviet losses, there was rough numerical parity between the two armies; and by the time of the battle of Warsaw, the Poles might have even had a slight advantage in numbers and logistics.[4] Among the major formations on the Polish side was the First Polish Army.

Logistics and plans

Logistics, nonetheless, were very bad for both armies, supported by whatever equipment was left over from World War I or could be captured. The Polish Army, for example, employed guns made in five countries, and rifles manufactured in six, each using different ammunition.[69] The Soviets had many military depots at their disposal, left by withdrawing German armies in 1918–1919, and modern French armaments captured in great numbers from the White Russians and the Allied expeditionary forces in the Russian Civil War. Still, they suffered a shortage of arms; both the Red Army and the Polish forces were grossly underequipped by Western standards.[69]

The Soviet High Command planned a new offensive in late April/May. Since March 1919, Polish intelligence was aware that the Soviets had prepared for a new offensive and the Polish High Command decided to launch their own offensive before their opponents.[22][26] The plan for Operation Kiev was to beat the Red Army on Poland's southern flank and install a Polish-friendly Petlura Government in Ukraine.[22]

Kiev Offensive

Until April, the Polish forces had been slowly but steadily advancing eastward. The new Latvian Government requested and obtained Polish help in capturing Daugavpils. The city fell after heavy fighting at the Battle of Daugavpils in January and was handed over to the Latvians.[57] By March, Polish forces had driven a wedge between Soviet forces to the north (Belorussia) and south (Ukraine).

On 24 April, Poland began its main offensive, Operation Kiev. Its stated goal was the creation of an independent Ukraine[22] that would become part of Piłsudski's project of a "Międzymorze" Federation. Poland's forces were assisted by 15,000 Ukrainian soldiers under Symon Petlura, representing the Ukrainian People's Republic.[62]

On 26 April, in his "Call to the People of Ukraine", Piłsudski told his audience that "the Polish Army would only stay as long as necessary until a legal Ukrainian government took control over its own territory".[70] Despite this, many Ukrainians were just as anti-Polish as anti-Bolshevik,[31] and resented the Polish advance.[22]

The Polish 3rd Army easily won border clashes with the Red Army in Ukraine but the Reds withdrew with minimal losses. Subsequently, the combined Polish–Ukrainian forces entered an abandoned Kiev on 7 May, encountering only token resistance.[22]

This Polish military thrust was met with Red Army counter-attacks on 29 May.[14] Polish forces in the area, preparing for an offensive towards Zhlobin, managed to hold their ground, but were unable to start their own planned offensive. In the north, Polish forces had fared much worse. The Polish 1st Army was defeated and forced to retreat, pursued by the Russian 15th Army, which recaptured territories between the Western Dvina and Berezina rivers. Polish forces attempted to take advantage of the exposed flanks of the attackers but the enveloping forces failed to stop the Soviet advance. At the end of May, the front had stabilised near the small river Auta River, and Soviet forces began preparing for the next push.

On 24 May 1920, the Polish forces in the south were engaged for the first time by Semyon Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army (Konarmia). Repeated attacks by Budyonny's Cossack cavalry broke the Polish–Ukrainian front on the 5th of June.[14] The Soviets then deployed mobile cavalry units to disrupt the Polish rearguard, targeting communications and logistics. By 10 June, Polish armies were in retreat along the entire front. On 13 June, the Polish Army, along with Petlura's Ukrainian troops, abandoned Kiev to the Red Army.

String of Soviet victories

On 30 May 1920 General Aleksei Brusilov, the last Tsarist Commander-in-Chief, published in Pravda an appeal entitled "To All Former Officers, Wherever They Might Be", encouraging them to forgive past grievances and to join the Red Army.[71] Brusilov considered it as a patriotic duty of all Russian officers to join hands with the Bolshevik Government, that in his opinion was defending Russia against foreign invaders. Lenin also spotted the use of Russian patriotism. Thus, the Central Committee appealed to the "respected citizens of Russia" to defend the Soviet republic against a Polish usurpation. Russia's counter-offensive was indeed boosted by Brusilov's engagement; 14,000 officers and over 100,000 deserters enlisted in or returned to the Red Army, and thousands of civilian volunteers contributed to the effort.[72] The commander of the Polish 3rd Army in Ukraine, General Edward Rydz-Śmigły, decided to break through the Soviet line toward the north-west. Polish forces in Ukraine managed to withdraw relatively unscathed, but were unable to support the northern front and reinforce the defences at the Auta River for the decisive battle that was soon to take place there.[73]

Due to insufficient forces, Poland's 320-kilometre-long (200 mi) front was manned by a thin line of 120,000 troops backed by some 460 artillery pieces with no strategic reserves. This approach to holding ground harked back to the World War I practice of "establishing a fortified line of defense". It had shown some merit on the Western Front saturated with troops, machine guns, and artillery. Poland's eastern front, however, was weakly manned, supported with inadequate artillery, and had almost no fortifications.[73]

Against the Polish line the Red Army gathered its Northwest Front led by the young General Mikhail Tukhachevsky. Their numbers exceeded 108,000 infantry and 11,000 cavalry, supported by 722 artillery pieces and 2,913 machine guns. The Soviets at some crucial places outnumbered the Poles four-to-one.[73]

Tukhachevsky launched his offensive on 4 July, along the Smolensk–Brest-Litovsk axis, crossing the Auta and Berezina rivers.[14] The northern 3rd Cavalry Corps, led by Gayk Bzhishkyan (Gay Dmitrievich Gay, Gaj-Chan), were to envelop Polish forces from the north, moving near the Lithuanian and Prussian border (both of these belonging to nations hostile to Poland). The 4th, 15th, and 3rd Armies were to push west, supported from the south by the 16th Army and Mozyr Group. For three days the outcome of the battle hung in the balance, but Soviet numerical superiority proved decisive and by 7 July Polish forces were in full retreat along the entire front. However, due to the stubborn defence by Polish units, Tukhachevsky's plan to break through the front and push the defenders south-west into the Pinsk Marshes failed.[73]

Polish resistance was offered again on a line of "German trenches", a line of heavy World War I field fortifications that presented an opportunity to stem the Red Army offensive. However, the Polish troops were insufficient in number. Soviet forces found a weakly defended part of the front and broke through. Gaj-Chan and Lithuanian forces captured Vilnius on 14 July, forcing the Poles into retreat again. In Galicia to the south, General Semyon Budyonny's cavalry advanced far into the Polish rear, capturing Brody and approaching Lwów and Zamość. In early July, it became clear to the Poles that the Soviets' objectives were not limited to pushing their borders westwards. Poland's very independence was at stake.[74]

Soviet forces moved forward at the remarkable rate of 32 kilometres (20 mi) a day. Grodno in Belarus fell on 19 July; Brest-Litovsk fell on 1 August. The Polish attempted to defend the Bug River line with 4th Army and Grupa Poleska units, but were able to delay the Red Army advance for only one week. After crossing the Narew River on 2 August, the Soviet Northwest Front was only 97 kilometres (60 mi) from Warsaw.[14] The Brest-Litovsk fortress, which became the headquarters of the planned Polish counter-offensive, fell to the 16th Army in the first attack. The Soviet South-west Front pushed the Polish forces out of Ukraine. Stalin had then disobeyed his orders and ordered his forces to close on Zamość, as well as Lwów – the largest city in southeastern Poland and an important industrial center, garrisoned by the Polish 6th Army. The city was soon besieged. This created a hole in the lines of the Red Army, but at the same time opened the way to the Polish capital. Five Soviet armies approached Warsaw.

Polish forces in Galicia near Lwów launched a successful counter-offensive to slow down the Red Army advance. This stopped the retreat of Polish forces on the southern front. However, the worsening situation near the Polish capital of Warsaw prevented the Poles from continuing that southern counter-offensive and pushing east. Forces were mustered to take part in the coming battle for Warsaw.[75]

Diplomatic front, part 2

With the tide turning against Poland, Piłsudski's political power weakened, while his opponents', including Roman Dmowski's, rose. Piłsudski did manage to regain his influence, especially over the military, almost at the last moment – as the Soviet forces were approaching Warsaw. The Polish political scene had begun to unravel in panic, with the government of Leopold Skulski resigning in early June.

Meanwhile, the Soviet leadership's confidence soared.[76] In a telegram, Lenin exclaimed: "We must direct all our attention to preparing and strengthening the Western Front. A new slogan must be announced: 'Prepare for war against Poland'."[77] Soviet Communist theorist Nikolay Bukharin, writer for the newspaper Pravda, wished for the resources to carry the campaign beyond Warsaw "right up to London and Paris".[78] General Tukhachevsky's order of the day, 2 July 1920, read: "To the West! Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to worldwide conflagration. March on Vilno, Minsk, Warsaw!"[73] and "onward to Berlin over the corpse of Poland!"[22] The increasing hope of certain victory, however, gave rise to political intrigues between Soviet commanders.[79]

By order of the Soviet Communist Party, a Polish puppet government,[80] the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee (Polish: Tymczasowy Komitet Rewolucyjny Polski, TKRP), had been formed on 28 July in Białystok to organise administration of the Polish territories captured by the Red Army.[22] The TKRP had very little support from the ethnic Polish population and recruited its supporters mostly from the ranks of minorities, primarily Jews.[31] At the height of the Polish–Soviet conflict, Jews had been subject to anti-semitic violence by Polish forces, who considered Jews a potential threat, and who often accused Jews as being the masterminds of Russian Bolshevism;[81][82] during the Battle of Warsaw, the Polish Government interned all Jewish volunteers and sent Jewish volunteer officers to an internment camp.[83][84]

In early July 1920, Prime Minister Władysław Grabski travelled to the Spa Conference in Belgium to request assistance.[85] The Allied representatives were largely unamenable towards Polish demands.[85] Grabski signed an agreement containing several terms: that Polish forces withdraw to the Curzon Line, which the Allies had published in December 1919, delineating Poland's ethnographic frontier; that it participate in a subsequent peace conference; and that the questions of sovereignty over Vilnius, Eastern Galicia, Cieszyn Silesia, and Danzig be remanded to the Allies.[85] Vague promises of Allied support were made in exchange.[85]

On 11 July 1920, the Government of Great Britain sent a telegram to the Soviets, signed by Curzon, which has been described as a de facto ultimatum.[86] It requested that the Soviets halt their offensive at the Curzon line and accept it as a temporary border with Poland, until a permanent border could be established in negotiations.[22] In case of Soviet refusal, the British threatened to assist Poland with all the means available, which, in reality, were limited by the internal political situation in the United Kingdom.[87] On 17 July, the Bolsheviks refused[22] and made a counter-offer to negotiate a peace treaty directly with Poland. The British government responded by threatening to cut off the ongoing trade negotiations if the Soviets conducted further offensives against Poland. These threat were ignored by the Soviets.[22]

On 6 August 1920, the UK Labour Party published a pamphlet stating that the workers would (and should) never take part in the war as Poland's allies, and labour unions blocked supplies to the expeditionary force assisting Russian Whites in Arkhangelsk. French Socialists, in their newspaper L'Humanité, declared: "Not a man, not a sou, not a shell for reactionary and Capitalist Poland. Long live the Russian Revolution! Long live the Workmen's International!"[73] Poland also suffered setbacks due to sabotage and delays in deliveries of war supplies, when workers in Czechoslovakia and Germany refused to transit such materials to Poland.[22] On 6 August the Polish Government issued an "Appeal to the World", disputing charges of Polish imperialism, stressing Poland's determination for self-determination and the dangers of Bolshevik invasion of Europe.[88]

Poland's neighbour Lithuania had been engaged in serious disputes with Poland over the city of Vilnius and the borderlands surrounding Sejny and Suwałki. A 1919 Polish attempt to take control over the entire nation by a coup had additionally disrupted their relationship.[89] The Soviet and Lithuanian governments signed the Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty of 1920 on 12 July; this treaty recognised Vilnius as part of Lithuania. The treaty contained a secret clause allowing Soviet forces unrestricted movement within Soviet-recognised Lithuanian territory during any Soviet war with Poland; this clause would lead to questions regarding the issue of Lithuanian neutrality in the ongoing Polish–Soviet War.[90][91] The Lithuanians also provided the Soviets with logistical support.[91] Despite Lithuanian support, the Soviets did not transfer Vilnius to the Lithuanians till just before the city was recaptured by the Polish forces (in late August), instead up till that time the Soviets encouraged their own, pro-Communist Lithuanian Government, Litbel, and were planning a pro-Communist coup in Lithuania.[92][93] The simmering conflict between Poland and Lithuania culminated in the Polish–Lithuanian War in August 1920.

Polish allies were few. France, continuing its policy of countering Bolshevism now that the Whites in Russia proper had been almost completely defeated, sent a 400-strong advisory group to Poland's aid in 1919. It consisted mostly of French officers, although it also included a few British advisers led by Lieutenant-General Sir Adrian Carton De Wiart. The French officers included a future President of France, Charles de Gaulle; during the war he won Poland's highest military decoration, the Virtuti Militari. In addition to the Allied advisors, France also facilitated the transit to Poland from France of the "Blue Army" in 1919: troops mostly of Polish origin, plus some international volunteers, formerly under French command in World War I. The army was commanded by the Polish general, Józef Haller. Hungary offered to send a 30,000 cavalry corps to Poland's aid, but the Czechoslovakian Government refused to allow them through, as there was a demilitarised zone on the borders after the Czechoslovak–Hungarian war that had ended only a few months before. Some trains with weapon supplies from Hungary did, however, arrive in Poland.

In mid-1920, the Allied Mission was expanded by some advisers (becoming the Inter-allied Mission to Poland). They included: French diplomat, Jean Jules Jusserand; Maxime Weygand, chief of staff to Marshal Ferdinand Foch, Supreme Commander of the victorious Entente; and British diplomat, Lord Edgar Vincent D'Abernon. The newest members of the mission achieved little; indeed, the crucial Battle of Warsaw was fought and won by the Poles before the mission could return and make its report. Nonetheless for many years, a myth persisted that it was the timely arrival of Allied forces that had saved Poland, a myth in which Weygand occupied the central role.[22][94] Nonetheless Polish-French co-operation would continue and French weaponry including infantry armament, artillery and Renault FT tanks were shipped to Poland to reinforce its military. Eventually, on 21 February 1921, France and Poland entered into a formal military alliance,[95] which became an important factor during the subsequent Soviet–Polish negotiations.

Battle of Warsaw

In early August, Polish and Soviet delegations met at Baranavichy and exchanged notes, but their talks came to nothing.[96]

On 10 August 1920, Soviet Cossack units under the command of Gayk Bzhishkyan crossed the Vistula River, planning to take Warsaw from the west while the main attack came from the east. On 13 August, an initial Soviet attack was repelled. The Polish 1st Army resisted a direct assault on Warsaw as well as stopping the assault at Radzymin.[14]

The Soviet Western Front commander, Mikhail Tukhachevsky, felt certain that all was going according to his plan. However, Polish military intelligence had decrypted the Red Army's radio messages,[97][98][99] and Tukhachevsky was actually falling into a trap set by Piłsudski and his Chief of Staff, Tadeusz Rozwadowski.[22] The Soviet advance across the Vistula River in the north was moving into an operational vacuum, as there were no sizable Polish forces in the area. On the other hand, south of Warsaw, where the fate of the war was about to be decided, Tukhachevsky had left only token forces to guard the vital link between the Soviet north-west and south-west fronts. Another factor that influenced the outcome of the war was the effective neutralisation of Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army, much feared by Piłsudski and other Polish commanders, in the battles around Lwów. At Tukhachevsky's insistence the Soviet High Command had ordered the 1st Cavalry Army to march north toward Warsaw and Lublin. However, Budyonny disobeyed the order due to a grudge between Tukhachevsky and Yegorov, commander of the south-west front.

Joseph Stalin, then chief political commissar of the South-western Front, was engaged at Lwów, about 320 kilometres from Warsaw.[100] The absence of his forces at the battle has been the subject of dispute.[100] A perception arose that his absence was due to his desire to achieve 'military glory' at Lwów.[73][100][101] Telegrams concerning the transfer of forces were exchanged.[102] Leon Trotsky interpreted Stalin's actions as insubordination; Richard Pipes asserts that Stalin '...almost certainly acted on Lenin's orders' in not moving the forces to Warsaw.[102] That the commander-in-chief Sergey Kamenev allowed such insubordination, issued conflicting and confusing orders and did not act with the decisiveness of a commander-in-chief contributed greatly to the problems and defeat the Red forces suffered at this critical junction of the war.

The Polish 5th Army under General Władysław Sikorski counter-attacked on 14 August from the area of the Modlin fortress, crossing the Wkra River. It faced the combined forces of the numerically and materially superior Soviet 3rd and 15th Armies. In one day the Soviet advance toward Warsaw and Modlin had been halted and soon turned into retreat. Sikorski's 5th Army pushed the exhausted Soviet formations away from Warsaw in a lightning operation. Polish forces advanced at a speed of thirty kilometers a day, soon destroying any Soviet hopes for completing their enveloping manoeuvre in the north. By 16 August, the Polish counter-offensive had been fully joined by Marshal Piłsudski's "Reserve Army." Precisely executing his plan, the Polish force, advancing from Warsaw (Colonel Wrzaliński's group) and the south (Polish 3rd and 4 Army), found a huge gap between the Soviet fronts and exploited the weakness of the Soviet "Mozyr Group" that was supposed to protect the weak link between the Soviet fronts. The Poles continued their northward offensive with two armies following and destroying the surprised enemy. They reached the rear of Tukhachevsky's forces, the majority of which were encircled by 18 August. Only that same day did Tukhachevsky, at his Minsk headquarters 480 kilometres (300 mi) east of Warsaw, become fully aware of the proportions of the Soviet defeat and ordered the remnants of his forces to retreat and regroup. He hoped to straighten his front line, halt the Polish attack, and regain the initiative, but the orders either arrived too late or failed to arrive at all.[73]

Soviet armies in the centre of the front fell into chaos. Tukhachevsky ordered a general retreat toward the Bug River, but by then he had lost contact with most of his forces near Warsaw, and all the Bolshevik plans had been thrown into disarray by communication failures.[73]

Bolshevik armies retreated in a disorganised fashion; entire divisions panicking and disintegrating. The Red Army's defeat was so great and unexpected that, at the instigation of Piłsudski's detractors, the Battle of Warsaw is often referred to in Poland as the "Miracle at the Vistula". Previously unknown documents from Polish Central Military Archive found in 2004 proved that the successful breaking of Red Army radio communications ciphers by Polish cryptographers played a great role in the victory (see Jan Kowalewski).[103]

Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army's advance toward Lwów was halted, first at the battle of Brody (29 July – 2 August),[14] and then on 17 August at the Battle of Zadwórze,[14] where a small Polish force sacrificed itself to prevent Soviet cavalry from seizing Lwów and stopping vital Polish reinforcements from moving toward Warsaw. Moving through weakly defended areas, Budyonny's cavalry reached the city of Zamość on 29 August and attempted to take it in the Battle of Zamość;[14] however, he soon faced an increasing number of Polish units diverted from the successful Warsaw counteroffensive. On 31 August, Budyonny's cavalry finally broke off its siege of Lwów and attempted to come to the aid of Soviet forces retreating from Warsaw. The Soviet forces were intercepted and defeated by Polish cavalry at the Battle of Komarów near Zamość, one of the largest cavalry battles since 1813 and one of the last cavalry battles in history. Although Budyonny's army managed to avoid encirclement, it suffered heavy losses and its morale plummeted.[14] The remains of Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army retreated towards Volodymyr-Volynskyi on 6 September[14] and were defeated shortly thereafter at the Battle of Hrubieszów.

Tukhachevsky managed to reorganise the eastward-retreating forces and in September established a new defensive line running from the Polish–Lithuanian border to the north to the area of Polesie, with the central point in the city of Grodno in Belarus. The Polish Army broke this line in the Battle of the Niemen River. Polish forces crossed the Niemen River and outflanked the Bolshevik forces, which were forced to retreat again.[14] Polish forces continued to advance east on all fronts,[14] repeating their successes from the previous year. After the early October Battle of the Szczara River, the Polish Army had reached the Ternopil–Dubno–Minsk–Drissa line.

In the south, Petliura's Ukrainian forces defeated the Bolshevik 14th Army and on 18 September took control of the left bank of the Zbruch river. During the next month they moved east to the line Yaruha on the Dniester–Sharhorod–Bar–Lityn.[104]

Conclusion

Soon after the Battle of Warsaw the Bolsheviks sued for peace. The Poles, exhausted, constantly pressured by the Western governments and the League of Nations, and with its army controlling the majority of the disputed territories, were willing to negotiate. The Soviets made two offers: one on 21 September and the other on 28 September. The Polish delegation made a counter-offer on 2 October. On 5 October, the Soviets offered amendments to the Polish offer, which Poland accepted. The Preliminary Treaty of Peace and Armistice Conditions between Poland on one side and Soviet Ukraine and Soviet Russia on the other was signed on 12 October, and the armistice went into effect on 18 October.[14][105] Ratifications were exchanged at Liepāja on 2 November. Long negotiations of the final peace treaty ensued.

Meanwhile, Petliura's Ukrainian forces, which now numbered 23,000 soldiers and controlled territories immediately to the east of Poland, planned an offensive in Ukraine for 11 November but were attacked by the Bolsheviks on 10 November. By 21 November, after several battles, they were driven into Polish-controlled territory.[104]

Aftermath

Despite the final retreat of Soviet forces and annihilation of their three field armies, historians do not universally agree on the question of victory.[N 4] The Poles claimed a successful defence of their state, while the Soviets claimed a repulse of the Polish eastward invasion of Ukraine and Belarus, which they viewed as a part of the foreign intervention in the Russian Civil War. Some British and American military historians argue that the Soviet failure to destroy the Polish Army decisively ended Soviet ambitions for international revolution.[106][31][107][108]

With the end of the Polish–Soviet War and the defeat of General Wrangel in 1920, the Red Army could divert its regular troops into the Tambov region of central Russia to crush the anti-Bolshevik peasant uprising.[109]

Peace negotiations

Due to their losses in and after the Battle of Warsaw, the Soviets offered the Polish peace delegation substantial territorial concessions in the contested borderland areas, closely resembling the border between the Russian Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth before the first partition of Poland in 1772.[110] Polish resources were exhausted, however, and Polish public opinion was opposed to a prolongation of the war.[22] The Polish Government was also pressured by the League of Nations, and the negotiations were controlled by Dmowski's National Democrats.

National Democrats cared little for Piłsudski's vision of reviving Międzymorze, the multi-cultural Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Piłsudski might have controlled the military, but parliament (Sejm) was controlled by Dmowski: Piłsudski's support lay in the territories in the East, which were controlled by the Bolsheviks at the time of the elections,[111] while the National Democrats' electoral support lay in central and western Poland.[111]

The National Democrats wanted only the territory that they viewed as 'ethnically or historically Polish' or possible to polonise.[112] Despite the Red Army's crushing defeat at Warsaw and the willingness of Soviet chief negotiator Adolf Joffe to concede almost all disputed territory,[110] the National Democrats' ideology allowed the Soviets to regain certain territories.[110] This post-war situation proved a death blow to the Międzymorze project.[22] The National Democrats also had few concerns about the fate of their Ukrainian ally, Petliura, and cared little that their political opponent, Piłsudski, felt honour-bound by his treaty obligations.[113] Thus, they did not hesitate to scrap the Warsaw Treaty between Poland and the Directorate of Ukraine.

The Peace of Riga was signed on 18 March 1921,[14] splitting the disputed territories in Belarus and Ukraine between Poland and the Soviet Union.[114][115]

Ukraine

The peace treaty, which Piłsudski called an "act of cowardice",[113] violated the terms of Poland's military alliance with the Directorate of Ukraine, which had explicitly prohibited a separate peace.[59] Ukrainian allies of Poland were interned by the Polish authorities.[114] This internment worsened relations between Poland and its Ukrainian minority: those who supported Petliura were angered by the betrayal of their Polish ally, anger that grew stronger because of the assimilationist policies of nationalist inter-war Poland towards its minorities.[116]

Belarus

The treaty partitioned Belarus, giving a portion of its territory to Poland and the other portion to the Soviets. Though the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic was not dissolved, its policies were determined by Moscow.[117] In response, Belarusian activists held a Congress of Representatives in Prague in the fall of 1921 to discuss the treaty. Vera Maslovskaya was sent as the delegate of the Białystok area and at the congress, she proposed a resolution to fight for unification. She sought independence of all Belarusian lands and denounced the partition. Though the convention did not adopt a proposal instituting armed conflict, they did pass Maslovskaya's proposal, which led to immediate retaliation from the Polish authorities. They infiltrated the underground network fighting for unification and arrest participants. Maslovskaya was arrested in 1922,[118][119] and tried in 1923, along with 45 other participants, including a sister and brother of Maslovskaya and several teachers and professionals, but most were peasants. Maslovskaya accepted all responsibility for the underground organisation, but specifically stated that she was guilty of no crime, having acted only to protect the interests of Belarus against foreign occupiers in a political and not military action. Unable to prove that the leaders had participated in armed rebellion, the court found them guilty of political crimes and sentenced the participants to six years in prison.[120]

Vilnius

The Polish military successes in the autumn of 1920 allowed Poland to capture the Vilnius region, where a Polish-dominated Governance Committee of Central Lithuania (Komisja Rządząca Litwy Środkowej) was formed. A plebiscite was conducted, and the Vilnius Sejm voted in favour of incorporation into Poland on 20 February 1922. This worsened Polish–Lithuanian relations for decades to come.[21] Despite this loss of territory for Lithuania, Alfred E. Senn argues that it was only the Polish victory against the Soviets in the Polish–Soviet War that derailed Soviet plans for westward expansion and gave Lithuania a period of interwar independence.[121]

War crimes and other controversies

The war and its aftermath also resulted in other controversies, such as the situation of prisoners of war of both sides,[9][122] treatment of the civilian population[123][124][125] and behavior of some commanders like Stanisław Bułak-Bałachowicz[126] or Vadim Yakovlev.[127] Another controversy concerned the pogroms of Jews, which caused the United States to send a commission led by Henry Morgenthau to investigate the matter.[128] More than one million Poles, living mostly in the disputed territories, remained in the Soviet Union, systematically persecuted by Soviet authorities for political, economic and religious reasons (see the Polish operation of the NKVD).

Developments in military strategy

The Polish–Soviet War influenced Polish military doctrine, which for the next 20 years would place emphasis on the mobility of elite cavalry units.[22] It also influenced Charles de Gaulle, then an instructor with the Polish Army who fought in several of the battles. He and Władysław Sikorski were the only military officers who, based on their experiences of this war, correctly predicted how the next one would be fought. Although they failed in the interbellum to convince their respective militaries to heed those lessons, early in World War II they rose to command of their armed forces in exile.[129]

Legacy

In 1943, during the course of World War II, the subject of Poland's eastern borders was re-opened, and they were discussed at the Tehran Conference. Winston Churchill argued in favour of the 1920 Curzon Line rather than the Treaty of Riga's borders, and an agreement among the Allies to that effect was reached at the Yalta Conference in 1945.[130] The Western Allies, despite having alliance treaties with Poland and despite Polish contribution, also left Poland within the Soviet sphere of influence, even though acceding to Poland being compensated with the bulk of the Former eastern territories of Germany. This became known as the Western betrayal.[131]

Until 1989, while Communists held power in the People's Republic of Poland, the Polish–Soviet War was omitted or minimised in Polish and other Soviet bloc countries' history books, or was presented as a foreign intervention during the Russian Civil War.[132]

Lieutenant Józef Kowalski, of Poland, was believed to be the last living veteran from this war. He was awarded the Order of Polonia Restituta on his 110th birthday by the president of Poland.[133] He died on 7 December 2013 at the age of 113. However, his age is not verified, and in any case, Alexander Imich, the world's verified oldest man when he died on 8 June 2014, aged 111, was a veteran from the same war, and therefore the real last living veteran.[134]

List of battles

See also

- Biuro Szyfrów

- Polish-Ukrainian War

- Soviet invasion of Poland

- Germany–Soviet Union relations, 1918–1941

Notes

- After 1920

- Battle of Daugavpils

- Volunteers

- Other names:

- Polish: Wojna polsko-bolszewicka, wojna polsko-sowiecka, wojna polsko-rosyjska 1919–1921, wojna polsko-radziecka (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

- Russian: Советско-польская война (Sovetsko-polskaya voyna, Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (Polsky front, Polish Front)

- See for instance Russo-Polish War in Encyclopædia Britannica

"The conflict began when the Polish head of state Józef Piłsudski formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlyura (21 April 1920) and their combined forces began to overrun Ukraine, occupying Kiev on 7 May." - For example: 1) Cisek 1990 Sąsiedzi wobec wojny 1920 roku. Wybór dokumentów.

2) Szczepański 1995 Wojna 1920 roku na Mazowszu i Podlasiu

3) Sikorski 1991 Nad Wisłą i Wkrą. Studium do polsko–radzieckiej wojny 1920 roku - Russian and Polish historians tend to assign victory to their respective countries. Outside assessments vary, mostly between calling the result a Polish victory or inconclusive.

References

- Davies 2003, p. 39

- Davies 2003, p. 142

- Davies 2003, p. 41

- Davies, White Eagle..., Polish edition, pp. 162, 202.

- Rudolph J. Rummel (1990). Lethal politics: Soviet genocide and mass murder since 1917. Transaction Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-56000-887-3. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- NDAP 2004 Official Polish government note about 2004 Rezmar, Karpus and Matveev book.

- Matveev 2006

- Norman Davies (1972). White eagle, red star: the Polish-Soviet war, 1919–20. Macdonald and Co. p. 247. ISBN 978-0356040134. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- (in Polish) Karpus, Zbigniew, Alexandrowicz Stanisław, Waldemar Rezmer, Zwycięzcy za drutami. Jeńcy polscy w niewoli (1919–1922). Dokumenty i materiały (Victors Behind Barbed Wire: Polish Prisoners of War, 1919–1922: Documents and materials), Toruń, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu, 1995, ISBN 978-83-231-0627-2.

- 47,055 names of Polish mortal casualties

- Rudycheva, Irina. The 100 notable Jews (100 знаменитых евреев).

- Aleksandr Rubtsov. How in Russia is being resurrected the imperial idea (Как в России воскрешается имперская идея). RBC.ru. 26 February 2016

- Norman Davies (2001), Heart of Europe. A Short History of Poland, Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, p. 75, ISBN 978-0-19-285152-9

- (in Polish) Wojna polsko-bolszewicka Archived 11 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Entry at Internetowa encyklopedia PWN. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- Davies 2003, p. 22

- (in Russian)"Соединение последовало явно в ущерб Литве, которая должна была уступить Польше Подляхию, Волынь и княжество Киевское", Соловьев С. "История России с древнейших времен", ISBN 978-5-17-002142-0, т.6, сс. 814–815

- Wandycz, Piotr S. (1974). "Part Two: The Age of Insurrections, 1830–64". The lands of partitioned Poland, 1795–1918. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295953588.

- Историк: 'В 1863 году белорусы поддержали не Польшу и Калиновского, а Россию и государя' [Historian: 'In 1863, Belarusians did not support Poland and Kalinowski, but Russia and its sovereign']. regnum.by (in Russian). 23 January 2013. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013.

- Fraser & Dunn 1996, p. 2

- Jukes, Simkins & Hickey 2002, pp. 84, 85

- Goldstein 1992, p. 51

- The Rebirth of Poland. University of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2006.

- Edward Mandell House; Charles Seymour (1921). What Really Happened at Paris. Scribner. p. 84. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

1919 curzon december ethnographic.

- Davies 2003, p. 21

- Adrian Hyde-Price (2001). Germany and European Order: Enlarging NATO and the EU. Manchester University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7190-5428-0. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Norman Davies, God's Playground. Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present. Columbia University Press, 2005 [1982]. ISBN 978-0-231-12819-3. Google Print, p. 292

- Davies 2003, p. 29

- Richard Pipes, David Brandenberger, Catherine A. Fitzpatrick, The unknown Lenin: from the secret archive, Yale University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-300-07662-2, Google Print, pp. 6–7

- Peter J. Boettke (1990). The Political Economy of Soviet Socialism: the Formative Years, 1918–1928. Springer. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-7923-9100-5. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- E. H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution; volume 3, p. 165, London: Macmillan ISBN 0333060040

- Ronald Grigor Suny, The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-508105-3, Google Print, p. 106

- Józef Pilsudski, Polish revolutionary and statesman, the first chief of state (1918–22) of the newly independent Poland established in November 1918. (Józef Pilsudski in Encyclopædia Britannica)

Released in Nov. 1918, [Pilsudski] returned to Warsaw, assumed command of the Polish armies, and proclaimed an independent Polish republic, which he headed. (Piłsudski, Joseph Archived 20 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine in Columbia Encyclopedia) - Timothy Snyder, Covert Polish missions across the Soviet Ukrainian border, 1928–1933 (p. 55, p. 56, p. 57, p. 58, p. 59, in Cofini, Silvia Salvatici (a cura di), Rubbettino, 2005).

Timothy Snyder, Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine, Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-300-10670-1, (p. 41, p. 42, p. 43) - "[Pilsudski] hoped to incorporate most of the territories of the defunct Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth into the future Polish state by structuring it as the Polish-led, multinational federation."

Aviel Roshwald, "Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires: Central Europe, the Middle East and Russia, 1914–1923", p. 37, Routledge (UK), 2001, ISBN 978-0-415-17893-8 - "Although the Polish premier and many of his associates sincerely wanted peace, other important Polish leaders did not. Josef Pilsudski, chief of state and creator of Polish army, was foremost among the latter. Pilsudski hoped to build not merely a Polish nation state but a greater federation of peoples under the aegis of Poland, which would replace Russia as the great power of Eastern Europe. Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine were all to be included. His plan called for a truncated and vastly reduced Russia, a plan that excluded negotiations prior to military victory."

Richard K Debo, Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918–192, Google Print, p. 59, McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-7735-0828-6. - "Pilsudski's program for a federation of independent states centered on Poland; in opposing the imperial power of both Russia and Germany it was in many ways a throwback to the romantic Mazzinian nationalism of Young Poland in the early nineteenth century. But his slow consolidation of dictatorial power betrayed the democratic substance of those earlier visions of national revolution as the path to human liberation"

James H. Billington, Fire in the Minds of Men, p. 432, Transaction Publishers, ISBN 978-0-7658-0471-6 - "Pilsudski dreamed of drawing all the nations situated between Germany and Russia into an enormous federation in which Poland, by virtue of its size, would be the leader, while Dmowski wanted to see a unitary Polish state, in which other Slav peoples would become assimilated."

Andrzej Paczkowski, The Spring Will Be Ours: Poland and the Poles from Occupation to Freedom, p. 10, Penn State Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-271-02308-3 - John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, W.W. Norton & Company, 2001, ISBN 978-0-393-02025-0, Google Print, p. 194

- Zbigniew Brzezinski in his introduction to Wacław Jędrzejewicz's "Pilsudski A Life For Poland" wrote: "Pilsudski's vision of Poland, paradoxically, was never attained. He contributed immensely to the creation of a modern Polish state, to the preservation of Poland from the Soviet invasion, yet he failed to create the kind of multinational commonwealth, based on principles of social justice and ethnic tolerance, to which he aspired in his youth. One may wonder how relevant was his image of such a Poland in the age of nationalism..."

- "Testament Marszałka Józefa Piłsudskiego". 13 May 2009.

- Zerkalo Nedeli, "A Belated Idealist." (Mirror Weekly), 22–28 May 2004."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 January 2006. Retrieved 13 November 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- One month before his death, Pilsudski told his aide: "My life is lost. I failed to create a Ukraine free from the Russians"

Oleksa Pidlutskyi, Postati XX stolittia, (Figures of the 20th century), Kiev, 2004, ISBN 978-966-8290-01-5, LCCN 2004-440333. Chapter "Józef Piłsudski: The Chief who Created Himself a State" reprinted in Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), Kiev, 3–9 February 2001. - MacMillan, Margaret, Paris 1919 : Six Months That Changed the World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2003, ISBN 978-0-375-76052-5, p. 212"

- Joseph Pilsudski Interview by Dmitry Merezhkovsky, 1921. Translated from the Russian by Harriet E Kennedy B.A. London & Edinburgh, Sampson Low, Marston & Co Ltd 1921. Piłsudski said: "Poland can have nothing to do with the restoration of old Russia. Anything rather than that–even Bolshevism."

- Pipes, Richard (1997). Russia under the Bolshevik Regime 1919–1924. Harvill. ISBN 978-1-86046-338-9.

- Richard Woytak, "Colonel Kowalewski and the Origins of Polish Code Breaking and Communication Interception", East European Quarterly, vol. XXI, no. 4 (January 1988), pp. 497–500.

- Robert J. Hanyok (2004). "Appendix B: Before Enigma: Jan Kowalewski and the Early Days of the Polish Cipher Bureau (1919–22)". Enigma: How the Poles Broke the Nazi Code. Hyppocrene Books. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-7818-0941-2.

- Grzegorz Nowik (2004). Zanim złamano Enigmę: Polski radiowywiad podczas wojny z bolszewicką Rosją 1918–1920 [Before Enigma was Broken: Polish radio-intelligence during the war against Bolshevik Russia 1918–1920]. Warsaw, RYTM Oficyna Wydawnicza. ISBN 978-83-7399-099-9.

- Urbanowski, op.cit., p. 90 (second tome)

- Peter Kenez, A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-31198-4, Google Books, p. 37

- (in Polish) Bohdan Urbankowski, Józef Piłsudski: marzyciel i strateg, (Józef Piłsudski: Dreamer and Strategist), Tom drugi (second tome), Wydawnictwo Alfa, Warsaw, 1997, ISBN 978-83-7001-914-3, p. 83

- Urbanowski, op.cit., p. 291

- Urbanowski, op.cit., p. 45 (second tome)

- Michael Palij, The Ukrainian-Polish defensive alliance, 1919–1921: an aspect of the Ukrainian revolution, CIUS Press, 1995, ISBN 978-1-895571-05-9, p. 87

- Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War, Pegasus Books LLC, 2005, ISBN 978-1-933648-15-6, p. 205

- Norman Davies. God's Playground: A History of Poland: 1795 to the Present. Oxford University Press. 2005. p. 377.

- "Lithuania through Polish eyes 1919–24". Lituanus.org. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- Watt, Richard (1979). Bitter Glory: Poland and its Fate 1918–1939. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-671-22625-1.

- Richard K Debo, Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918–1921, pp. 210–211, McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-7735-0828-6.

- Prof. Ruslan Pyrig, "Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the Bolsheviks: the price of political compromise", Zerkalo Nedeli, 30 September – 6 October 2006. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-10586-5 Google Books, p. 139

- Subtelny, O. (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 375.

- Davies, White Eagle..., Polish edition, p. 106

- Davies, White Eagle..., Polish edition, pp. 142–143

- Krivosheev, Grigoriy F. (1997) [1993]. "Table 7: Average Monthly Personal Strength of Fronts and Independent Armies in 1920". Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century. Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 17.

Numerical strength [Commanders/NCOs and men/Total]: 7th Independent Army: 13,583/141,070/154,653; Western Front: 26,272/355,799/382,071; South-Western Front: 17,231/265,276/282,507; Southern Front (against Wrangel): 26,576/395,731/422,307; Caucasian Front: 32,336/307,862/340,198; Turkestan Front: 10,688/150,167/160,855; 5th Independent Army: 9,432/104,778/114,210. // All numbers for the months July–August, except for Southern Front (against Wrangel), which is for the month of October.

- Davies, White Eagle..., Polish edition, p. 85.

- Janusz Cisek, Kosciuszko, We Are Here: American Pilots of the Kosciuszko Squadron in Defense of Poland, 1919–1921, McFarland & Company, 2002, ISBN 978-0-7864-1240-2, Google Print

- Davies 2003, p. 83

- Davies 2003, p. 85

- (in Polish), Włodzimierz Bączkowski, Włodzimierz Bączkowski – Czy prometeizm jest fikcją i fantazją?, Ośrodek Myśli Politycznej (quoting full text of "odezwa Józefa Piłsudskiego do mieszkańców Ukrainy"). Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- Вольдемар Николаевич Балязин (2007). Неофициальная история России [The Unofficial History of Russia] (in Russian). Olma Media Group. p. 595. ISBN 978-5-373-01229-4. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- Orlando Figes (1996). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. Pimlico. p. 699. ISBN 978-0-7126-7327-3.

Within weeks of Brusilov's appointment, 14,000 officers had joined the army to fight the Poles, thousands of civilians had volunteered for war-work, and well over 100,000 deserters had returned to the Red Army on the Western Front.

- Battle Of Warsaw 1920 by Witold Lawrynowicz; A detailed write-up, with bibliography Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Polish Militaria Collectors Association. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- Jerzy Lukowski, Hubert Zawadzki, A Concise History of Poland, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1, Google Print, p. 203

- A. Mongeon, The Polish–Russian War and the Fight for Polish Independence, 1918–1921. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- At a closed meeting of the 9th Conference of the Russian Communist Party on 22 September 1920, Lenin said, "We confronted the question: whether [...] to take advantage of the enthusiasm in our army and the advantage which we enjoyed to sovietize Poland... the defensive war against imperialism was over, we won it... We could and should take advantage of the military situation to begin an offensive war... we should poke about with bayonets to see whether the socialist revolution of the proletariat had not ripened in Poland... that somewhere near Warsaw lies not [only] the center of the Polish bourgeois government and the republic of capital, but the center of the whole contemporary system of international imperialism, and that circumstances enabled us to shake that system, and to conduct politics not in Poland but in Germany and England. In this manner, in Germany and England we created a completely new zone of proletarian revolution against global imperialism... By destroying the Polish army we are destroying the Versailles Treaty on which nowadays the entire system of international relations is based.....Had Poland become Soviet....the Versailles Treaty ...and with it the whole international system arising from the victories over Germany, would have been destroyed."

English translation quoted from Richard Pipes, Russia under the Bolshevik Regime, New York, 1993, pp. 181–182, with some stylistic modification in par 3, line 3, by A. M. Cienciala. This document was first published in a Russian historical periodical, Istoricheskii Arkhiv, vol. I, no. 1., Moscow,1992 and is cited through The Rebirth of Poland. University of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2006. - Lincoln, W. Bruce, Red Victory: a History of the Russian Civil War, Da Capo Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-306-80909-5, p. 405

- Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888–1938, Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0-19-502697-9, Google Print, p. 101

- Susan Weissman, Victor Serge: The Course is Set on Hope, Verso, 2001, ISBN 978-1-85984-987-3, Google Print, p. 39

- Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War, Pegasus Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1-933648-15-6, Google Print, p. 255

- David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzveig. The World Reacts to the Holocaust. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- Joanna B. Michlic. Poland's Threatening Other. University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

- Ezra Mendelsohn. The Jews of East Central Europe Between the World Wars. Indiana University Press, 1983.

- Norman Davies (2005). God's Playground: A History of Poland. Columbia University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-231-12819-3.

Notwithstanding the hostility of the Zionists, and of extreme Polish nationalists (who succeeded at the height of the Battle of Warsaw in persuading the authorities to intern all Jewish volunteers as potential sub-versionists), the majority of established Jewish leaders decided to co-operate with the government.

- Piotr Stefan Wandycz (1962). France and her eastern allies, 1919–1925: French-Czechoslovak-Polish relations from the Paris Peace Conference to Locarno. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-0-8166-5886-2. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- The Military History of the Soviet Union, Palgrave, 2002, ISBN 978-0-312-29398-7, Google Print, p. 41

- Jerzy Borzęcki, The Soviet-Polish peace of 1921 and the creation of interwar Europe, Yale University Press, 2008, pp. 79–81

- The Annual Register. Abebooks. 1921.

- Roy Francis Leslie (1983). The History of Poland Since 1863. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27501-9.

Lithuanian nationalism was fundamentally anti-Polish in character and Polish–Lithuanian relations deteriorated still further in August 1919 as a result of an attempted coup by the Polish Military Organization (POW) aimed at placing a pro-Polish government in power at Kaunas (Kovno).

- Łossowski, Piotr (2001). Litwa (in Polish). Warszawa: TRIO. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-83-85660-59-0.

- Łossowski, Piotr (1995). Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918–1920 (in Polish). Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza. pp. 126–128. ISBN 978-83-05-12769-1.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas; Vytautas Žalys; Alfred Erich Senn (1999). Ed. Edvardas Tuskenis (ed.). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 72–74. ISBN 978-0-312-22458-5.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (September 1962). "The Formation of the Lithuanian Foreign Office, 1918–1921". Slavic Review. 3 (21): 500–507. doi:10.2307/3000451. JSTOR 3000451.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- (in Polish) Janusz Szczepański, Kontrowersje Wokol Bitwy Warszawskiej 1920 Roku (Controversies surrounding the Battle of Warsaw in 1920). Mówią Wieki, online version.

- Edward Grosek, The Secret Treaties of History, XLIBRIS CORP, 2004, ISBN 978-1-4134-6745-1, p. 170

- Isaac Babel (2002). 1920 Diary. Yale University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-300-09313-1.

- (in Polish) Ścieżyński, Mieczysław, [Colonel of the (Polish) General Staff], Radjotelegrafja jako źrodło wiadomości o nieprzyjacielu (Radiotelegraphy as a Source of Intelligence on the Enemy), Przemyśl, [Printing and Binding Establishment of (Military) Corps District No. X HQ], 1928, 49 pp.

- (in Polish) Paweł Wroński, "Sensacyjne odkrycie: Nie było cudu nad Wisłą" ("A Remarkable Discovery: There Was No Miracle at the Vistula"), Gazeta Wyborcza, wiadomosci.gazeta.pl.

- Jan Bury, Polish Codebreaking During the Russo-Polish War of 1919–1920,

- Robert Service (historian) (2005). Stalin: a biography. Harvard University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-674-01697-2.

- Stalin: The Man and His Era, Beacon Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0-8070-7005-5, Google Print, p. 189

- Richard Pipes (1999). The unknown Lenin: from the secret archive. Yale University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-300-07662-2.

- Grzegorz Nowik, "Zanim złamano Enigmę. Polski radiowywiad podczas wojny z bolszewicką Rosją 1918–1920", 2004, ISBN 978-83-7399-099-9

- Kubijovic, V. (1963). Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopedia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 4, pp. 8–45.

- Fuller, J.F.C., The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Hunter Publishing, ISBN 0-586-08036-8.

- Davies, Norman, White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–20, Pimlico, 2003, ISBN 978-0-7126-0694-3. (First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972.) p. ix.

- Aleksander Gella, Development of Class Structure in Eastern Europe: Poland and Her Southern Neighbors, SUNY Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0-88706-833-1, Google Print, p. 23

- Singleton, Seth (September 1966). "The Tambov Revolt (1920–1921)". Slavic Review. 25 (3): 497–512. doi:10.2307/2492859. JSTOR 2492859.

- Norman Davies, God's Playground. Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present. Columbia University Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0-231-05352-5. Google Print, p. 504

- Timothy Snyder. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 68.