Butter

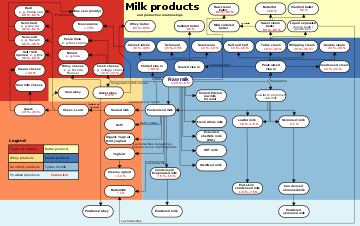

Butter is a dairy product made from the fat and protein components of milk or cream. It is a semi-solid emulsion at room temperature, consisting of approximately 80% butterfat. It is used at room temperature as a spread, melted as a condiment, and used as an ingredient in baking, sauce making, pan frying, and other cooking procedures.

Melted and solid butter | |

| Nutritional value per 1 US Tbsp (14.2g) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 101.8 kcal (426 kJ) |

0.01 g | |

| Sugars | 0.01 g |

11.52 g | |

| Saturated | 7.294 g |

| Trans | 0.465 g |

| Monounsaturated | 2.985 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 0.432 g |

0.12 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 12% 97.1 μg |

| Vitamin A | 355 IU |

| Vitamin B12 | 1% 0.024 μg |

| Vitamin E | 2% 0.33 mg |

| Vitamin K | 1% 0.99 μg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Cholesterol | 30.5 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

Most frequently made from cow's milk, butter can also be manufactured from the milk of other mammals, including sheep, goats, buffalo, and yaks. It is made by churning milk or cream to separate the fat globules from the buttermilk. Salt and food colorings are sometimes added to butter. Rendering butter, removing the water and milk solids, produces clarified butter or ghee, which is almost entirely butterfat.

Butter is a water-in-oil emulsion resulting from an inversion of the cream, where the milk proteins are the emulsifiers. Butter remains a firm solid when refrigerated, but softens to a spreadable consistency at room temperature, and melts to a thin liquid consistency at 32 to 35 °C (90 to 95 °F). The density of butter is 911 grams per litre (0.950 lb per US pint).[1] It generally has a pale yellow color, but varies from deep yellow to nearly white. Its natural, unmodified color is dependent on the source animal's feed and genetics, but the commercial manufacturing process commonly manipulates the color with food colorings like annatto[2] or carotene.

Etymology

The word butter derives (via Germanic languages) from the Latin butyrum,[3] which is the latinisation of the Greek βούτυρον (bouturon).[4][5] This may be a compound of βοῦς (bous), "ox, cow"[6] + τυρός (turos), "cheese", that is "cow-cheese".[7][8] The word turos ("cheese") is attested in Mycenaean Greek.[9] The latinized form is found in the name butyric acid, a compound found in rancid butter and dairy products such as Parmesan cheese.

In general use, the term "butter" refers to the spread dairy product when unqualified by other descriptors. The word commonly is used to describe puréed vegetable or seed and nut products such as peanut butter and almond butter. It is often applied to spread fruit products such as apple butter. Fats such as cocoa butter and shea butter that remain solid at room temperature are also known as "butters". Non-dairy items that have a dairy-butter consistency may use "butter" to call that consistency to mind, including food items such as maple butter and witch's butter and nonfood items such as baby bottom butter, hyena butter, and rock butter.

Production

Unhomogenized milk and cream contain butterfat in microscopic globules. These globules are surrounded by membranes made of phospholipids (fatty acid emulsifiers) and proteins, which prevent the fat in milk from pooling together into a single mass. Butter is produced by agitating cream, which damages these membranes and allows the milk fats to conjoin, separating from the other parts of the cream. Variations in the production method will create butters with different consistencies, mostly due to the butterfat composition in the finished product. Butter contains fat in three separate forms: free butterfat, butterfat crystals, and undamaged fat globules. In the finished product, different proportions of these forms result in different consistencies within the butter; butters with many crystals are harder than butters dominated by free fats.

Churning produces small butter grains floating in the water-based portion of the cream. This watery liquid is called buttermilk—although the buttermilk most common today is instead a directly fermented skimmed milk. The buttermilk is drained off; sometimes more buttermilk is removed by rinsing the grains with water. Then the grains are "worked": pressed and kneaded together. When prepared manually, this is done using wooden boards called scotch hands. This consolidates the butter into a solid mass and breaks up embedded pockets of buttermilk or water into tiny droplets.

Commercial butter is about 80% butterfat and 15% water; traditionally made butter may have as little as 65% fat and 30% water. Butterfat is a mixture of triglyceride, a triester derived from glycerol and three of any of several fatty acid groups.[10] Butter becomes rancid when these chains break down into smaller components, like butyric acid and diacetyl. The density of butter is 0.911 g/cm3 (0.527 oz/in3), about the same as ice.

In some countries, butter is given a grade before commercial distribution.

Types

Before modern factory butter making, cream was usually collected from several milkings and was therefore several days old and somewhat fermented by the time it was made into butter. Butter made from a fermented cream is known as cultured butter. During fermentation, the cream naturally sours as bacteria convert milk sugars into lactic acid. The fermentation process produces additional aroma compounds, including diacetyl, which makes for a fuller-flavored and more "buttery" tasting product.[11](p35) Today, cultured butter is usually made from pasteurized cream whose fermentation is produced by the introduction of Lactococcus and Leuconostoc bacteria.

Another method for producing cultured butter, developed in the early 1970s, is to produce butter from fresh cream and then incorporate bacterial cultures and lactic acid. Using this method, the cultured butter flavor grows as the butter is aged in cold storage. For manufacturers, this method is more efficient, since aging the cream used to make butter takes significantly more space than simply storing the finished butter product. A method to make an artificial simulation of cultured butter is to add lactic acid and flavor compounds directly to the fresh-cream butter; while this more efficient process is claimed to simulate the taste of cultured butter, the product produced is not cultured but is instead flavored.

Dairy products are often pasteurized during production to kill pathogenic bacteria and other microbes. Butter made from pasteurized fresh cream is called sweet cream butter. Production of sweet cream butter first became common in the 19th century, with the development of refrigeration and the mechanical cream separator.[11](p33) Butter made from fresh or cultured unpasteurized cream is called raw cream butter. While butter made from pasteurized cream may keep for several months, raw cream butter has a shelf life of roughly ten days.

Throughout continental Europe, cultured butter is preferred, while sweet cream butter dominates in the United States and the United Kingdom. Cultured butter is sometimes labeled "European-style" butter in the United States, although cultured butter is made and sold by some, especially Amish, dairies. Commercial raw cream butter is virtually unheard-of in the United States. Raw cream butter is generally only found made at home by consumers who have purchased raw whole milk directly from dairy farmers, skimmed the cream themselves, and made butter with it. It is rare in Europe as well.[11](p34)

Several "spreadable" butters have been developed. These remain softer at colder temperatures and are therefore easier to use directly out of refrigeration. Some methods modify the makeup of the butter's fat through chemical manipulation of the finished product, some manipulate the cattle's feed, and some incorporate vegetable oil into the butter. "Whipped" butter, another product designed to be more spreadable, is aerated by incorporating nitrogen gas—normal air is not used to avoid oxidation and rancidity.

All categories of butter are sold in both salted and unsalted forms. Either granular salt or a strong brine are added to salted butter during processing. In addition to enhanced flavor, the addition of salt acts as a preservative. The amount of butterfat in the finished product is a vital aspect of production. In the United States, products sold as "butter" must contain at least 80% butterfat. In practice, most American butters contain slightly more than that, averaging around 81% butterfat. European butters generally have a higher ratio—up to 85%.

Clarified butter is butter with almost all of its water and milk solids removed, leaving almost-pure butterfat. Clarified butter is made by heating butter to its melting point and then allowing it to cool; after settling, the remaining components separate by density. At the top, whey proteins form a skin, which is removed. The resulting butterfat is then poured off from the mixture of water and casein proteins that settle to the bottom.[11](p37)

Ghee is clarified butter that has been heated to around 120 °C (250 °F) after the water evaporated, turning the milk solids brown. This process flavors the ghee, and also produces antioxidants that help protect it from rancidity. Because of this, ghee can keep for six to eight months under normal conditions.[11](p37)

Whey butter

Cream may be separated (usually by a centrifugal separator) from whey instead of milk, as a byproduct of cheese-making. Whey butter may be made from whey cream. Whey cream and butter have a lower fat content and taste more salty, tangy and "cheesy".[12] They are also cheaper than "sweet" cream and butter. The fat content of whey is low, so 1000 pounds of whey will typically give 3 pounds of butter.[13][14]

European butters

There are several butters produced in Europe with protected geographical indications; these include:

- Beurre d'Ardenne, from Belgium

- Beurre d'Isigny, from France

- Beurre Charentes-Poitou (Which also includes: Beurre des Charentes and Beurre des Deux-Sèvres under the same classification), from France

- Beurre Rose, from Luxembourg

- Mantequilla de Soria, from Spain

- Mantega de l'Alt Urgell i la Cerdanya, from Spain

- Rucava white butter (Rucavas baltais sviests), from Latvia[15]

History

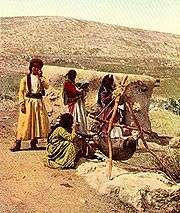

The earliest butter would have been from sheep or goat's milk; cattle are not thought to have been domesticated for another thousand years.[16] An ancient method of butter making, still used today in parts of Africa and the Near East, involves a goat skin half filled with milk, and inflated with air before being sealed. The skin is then hung with ropes on a tripod of sticks, and rocked until the movement leads to the formation of butter.

In the Mediterranean climate, unclarified butter spoils quickly, unlike cheese, so it is not a practical method of preserving the nutrients of milk. The ancient Greeks and Romans seemed to have considered butter a food fit more for the northern barbarians. A play by the Greek comic poet Anaxandrides refers to Thracians as boutyrophagoi, "butter-eaters".[17] In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder calls butter "the most delicate of food among barbarous nations" and goes on to describe its medicinal properties.[18] Later, the physician Galen also described butter as a medicinal agent only.[19]

Historian and linguist Andrew Dalby says most references to butter in ancient Near Eastern texts should more correctly be translated as ghee. Ghee is mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea as a typical trade article around the first century CE Arabian Sea, and Roman geographer Strabo describes it as a commodity of Arabia and Sudan.[17] In India, ghee has been a symbol of purity and an offering to the gods—especially Agni, the Hindu god of fire—for more than 3000 years; references to ghee's sacred nature appear numerous times in the Rigveda, circa 1500–1200 BCE. The tale of the child Krishna stealing butter remains a popular children's story in India today. Since India's prehistory, ghee has been both a staple food and used for ceremonial purposes, such as fueling holy lamps and funeral pyres.

Middle Ages

In the cooler climates of northern Europe, people could store butter longer before it spoiled. Scandinavia has the oldest tradition in Europe of butter export trade, dating at least to the 12th century.[20] After the fall of Rome and through much of the Middle Ages, butter was a common food across most of Europe—but had a low reputation, and so was consumed principally by peasants. Butter slowly became more accepted by the upper class, notably when the early 16th century Roman Catholic Church allowed its consumption during Lent. Bread and butter became common fare among the middle class and the English, in particular, gained a reputation for their liberal use of melted butter as a sauce with meat and vegetables.[11](p33)

In antiquity, butter was used for fuel in lamps, as a substitute for oil. The Butter Tower of Rouen Cathedral was erected in the early 16th century when Archbishop Georges d'Amboise authorized the burning of butter during Lent, instead of oil, which was scarce at the time.[21]

Across northern Europe, butter was sometimes treated in a manner unheard-of today: it was packed into barrels (firkins) and buried in peat bogs, perhaps for years. Such "bog butter" would develop a strong flavor as it aged, but remain edible, in large part because of the unique cool, airless, antiseptic and acidic environment of a peat bog. Firkins of such buried butter are a common archaeological find in Ireland; the National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology has some containing "a grayish cheese-like substance, partially hardened, not much like butter, and quite free from putrefaction." The practice was most common in Ireland in the 11th–14th centuries; it ended entirely before the 19th century.[20]

Industrialization

Like Ireland, France became well known for its butter, particularly in Normandy and Brittany. Butter consumption in London in the mid 1840s was estimated at 15,357 tons annually.[22] By the 1860s, butter had become so in demand in France that Emperor Napoleon III offered prize money for an inexpensive substitute to supplement France's inadequate butter supplies. A French chemist claimed the prize with the invention of margarine in 1869. The first margarine was beef tallow flavored with milk and worked like butter; vegetable margarine followed after the development of hydrogenated oils around 1900.

Until the 19th century, the vast majority of butter was made by hand, on farms. The first butter factories appeared in the United States in the early 1860s, after the successful introduction of cheese factories a decade earlier. In the late 1870s, the centrifugal cream separator was introduced, marketed most successfully by Swedish engineer Carl Gustaf Patrik de Laval.[23] This dramatically sped up the butter-making process by eliminating the slow step of letting cream naturally rise to the top of milk. Initially, whole milk was shipped to the butter factories, and the cream separation took place there. Soon, though, cream-separation technology became small and inexpensive enough to introduce an additional efficiency: the separation was accomplished on the farm, and the cream alone shipped to the factory. By 1900, more than half the butter produced in the United States was factory made; Europe followed suit shortly after.

In 1920, Otto Hunziker authored The Butter Industry, Prepared for Factory, School and Laboratory,[24] a well-known text in the industry that enjoyed at least three editions (1920, 1927, 1940). As part of the efforts of the American Dairy Science Association, Professor Hunziker and others published articles regarding: causes of tallowiness[25] (an odor defect, distinct from rancidity, a taste defect); mottles[26] (an aesthetic issue related to uneven color); introduced salts;[27] the impact of creamery metals[28] and liquids;[29] and acidity measurement.[30] These and other ADSA publications helped standardize practices internationally.

Butter also provided extra income to farm families. They used wood presses with carved decoration to press butter into pucks or small bricks to sell at nearby markets or general stores. The decoration identified the farm that produced the butter. This practice continued until production was mechanized and butter was produced in less decorative stick form.[31] Today, butter presses remain in use for decorative purposes.

Butter consumption declined in most western nations during the 20th century, mainly because of the rising popularity of margarine, which is less expensive and, until recent years, was perceived as being healthier. In the United States, margarine consumption overtook butter during the 1950s,[32] and it is still the case today that more margarine than butter is eaten in the U.S. and the EU.[33]

Packaging

United States

In the United States, butter has traditionally been made into small, rectangular blocks by means of a pair of wooden butter paddles. It is usually produced in 4-ounce (1⁄4 lb; 110 g) sticks that are individually wrapped in waxed or foiled paper, and sold as a 1 pound (0.45 kg) package of 4 sticks. This practice is believed to have originated in 1907, when Swift and Company began packaging butter in this manner for mass distribution.[34]

Due to historical differences in butter printers (machines that cut and package butter),[35] 4-ounce sticks are commonly produced in two different shapes:

- The dominant shape east of the Rocky Mountains is the Elgin, or Eastern-pack shape, named for a dairy in Elgin, Illinois. The sticks measure 4 3⁄4 by 1 1⁄4 by 1 1⁄4 inches (121 mm × 32 mm × 32 mm) and are typically sold stacked two by two in elongated cube-shaped boxes.[35]

- West of the Rocky Mountains, butter printers standardized on a different shape that is now referred to as the Western-pack shape. These butter sticks measure 3 1⁄4 by 1 1⁄2 by 1 1⁄2 inches (83 mm × 38 mm × 38 mm)[36] and are usually sold with four sticks packed side-by-side in a flat, rectangular box.[35]

Most butter dishes are designed for Elgin-style butter sticks.[35]

Butter stick wrappers are usually marked with divisions for 8 US tablespoons (120 ml), which is less than their actual volume: the Elgin-pack shape is 8.22 US tbsp, while the Western-pack shape is 8.10 US tbsp. The printing on unsalted ("sweet") butter wrappers is typically red, while that for salted butter is typically blue.

Elsewhere

Outside of the United States, the shape of butter packages is approximately the same, but the butter is measured for sale and cooking by mass (rather than by volume or unit/stick), and is sold in 250 g (8.8 oz) and 500 g (18 oz) packages. The wrapper is usually a foil and waxed-paper laminate. (The waxed paper is now a siliconised substitute, but is still referred to in some places as parchment, from the wrapping used in past centuries; and the term 'parchment-wrapped' is still employed where the paper alone is used, without the foil laminate.)

Butter for commercial and industrial use is packaged in plastic buckets, tubs, or drums, in quantities and units suited to the local market.

Worldwide

In 1997, India produced 1,470,000 metric tons (1,620,000 short tons) of butter, most of which was consumed domestically.[37] Second in production was the United States (522,000 t or 575,000 short tons), followed by France (466,000 t or 514,000 short tons), Germany (442,000 t or 487,000 short tons), and New Zealand (307,000 t or 338,000 short tons). France ranks first in per capita butter consumption with 8 kg per capita per year.[38] In terms of absolute consumption, Germany was second after India, using 578,000 metric tons (637,000 short tons) of butter in 1997, followed by France (528,000 t or 582,000 short tons), Russia (514,000 t or 567,000 short tons), and the United States (505,000 t or 557,000 short tons). New Zealand, Australia, and the Ukraine are among the few nations that export a significant percentage of the butter they produce.[39]

Different varieties are found around the world. Smen is a spiced Moroccan clarified butter, buried in the ground and aged for months or years. A similar product is maltash of the Hunza Valley, where cow and yak butter can be buried for decades, and is used at events such as weddings.[40] Yak butter is a specialty in Tibet; tsampa, barley flour mixed with yak butter, is a staple food. Butter tea is consumed in the Himalayan regions of Tibet, Bhutan, Nepal and India. It consists of tea served with intensely flavored—or "rancid"—yak butter and salt. In African and Asian developing nations, butter is traditionally made from sour milk rather than cream. It can take several hours of churning to produce workable butter grains from fermented milk.[41]

Storage

Normal butter softens to a spreadable consistency around 15 °C (60 °F), well above refrigerator temperatures. The "butter compartment" found in many refrigerators may be one of the warmer sections inside, but it still leaves butter quite hard. Until recently, many refrigerators sold in New Zealand featured a "butter conditioner", a compartment kept warmer than the rest of the refrigerator—but still cooler than room temperature—with a small heater.[42] Keeping butter tightly wrapped delays rancidity, which is hastened by exposure to light or air, and also helps prevent it from picking up other odors. Wrapped butter has a shelf life of several months at refrigerator temperatures.[43] Butter can also be frozen to further extend its storage life.

"French butter dishes" or "Acadian butter dishes" have a lid with a long interior lip, which sits in a container holding a small amount of water. Usually the dish holds just enough water to submerge the interior lip when the dish is closed. Butter is packed into the lid. The water acts as a seal to keep the butter fresh, and also keeps the butter from overheating in hot temperatures. This method lets butter sit on a countertop for several days without spoiling.

In cooking and gastronomy

Donnez-moi du beurre, encore du beurre, toujours du beurre!

— Fernand Point

Butter has been considered indispensable in French cuisine since the 17th century.[44] Chefs and cooks have extolled its importance: Fernand Point said "Donnez-moi du beurre, encore du beurre, toujours du beurre!" 'Give me butter, more butter, still more butter!';[45] Julia Child said "With enough butter, anything is good."[46]

Once butter is softened, spices, herbs, or other flavoring agents can be mixed into it, producing what is called a compound butter or composite butter (sometimes also called composed butter). Compound butters can be used as spreads, or cooled, sliced, and placed onto hot food to melt into a sauce. Sweetened compound butters can be served with desserts; such hard sauces are often flavored with spirits.

Melted butter plays an important role in the preparation of sauces, notably in French cuisine. Beurre noisette (hazelnut butter) and Beurre noir (black butter) are sauces of melted butter cooked until the milk solids and sugars have turned golden or dark brown; they are often finished with an addition of vinegar or lemon juice.[11](p36) Hollandaise and béarnaise sauces are emulsions of egg yolk and melted butter; they are in essence mayonnaises made with butter instead of oil. Hollandaise and béarnaise sauces are stabilized with the powerful emulsifiers in the egg yolks, but butter itself contains enough emulsifiers—mostly remnants of the fat globule membranes—to form a stable emulsion on its own.[11](p635–636) Beurre blanc (white butter) is made by whisking butter into reduced vinegar or wine, forming an emulsion with the texture of thick cream. Beurre monté (prepared butter) is melted but still emulsified butter; it lends its name to the practice of "mounting" a sauce with butter: whisking cold butter into any water-based sauce at the end of cooking, giving the sauce a thicker body and a glossy shine—as well as a buttery taste.[11](p632)

In Poland, the butter lamb (Baranek wielkanocny) is a traditional addition to the Easter Meal for many Polish Catholics. Butter is shaped into a lamb either by hand or in a lamb-shaped mould. Butter is also used to make edible decorations to garnish other dishes.

Butter is used for sautéing and frying, although its milk solids brown and burn above 150 °C (250 °F)—a rather low temperature for most applications. The smoke point of butterfat is around 200 °C (400 °F), so clarified butter or ghee is better suited to frying.[11](p37) Ghee has always been a common frying medium in India, where many avoid other animal fats for cultural or religious reasons.

Butter fills several roles in baking, where it is used in a similar manner as other solid fats like lard, suet, or shortening, but has a flavor that may better complement sweet baked goods. Many cookie doughs and some cake batters are leavened, at least in part, by creaming butter and sugar together, which introduces air bubbles into the butter. The tiny bubbles locked within the butter expand in the heat of baking and aerate the cookie or cake. Some cookies like shortbread may have no other source of moisture but the water in the butter. Pastries like pie dough incorporate pieces of solid fat into the dough, which become flat layers of fat when the dough is rolled out. During baking, the fat melts away, leaving a flaky texture. Butter, because of its flavor, is a common choice for the fat in such a dough, but it can be more difficult to work with than shortening because of its low melting point. Pastry makers often chill all their ingredients and utensils while working with a butter dough.

Nutritional information

As butter is essentially just the milk fat, it contains only traces of lactose, so moderate consumption of butter is not a problem for lactose intolerant people.[47] People with milk allergies may still need to avoid butter, which contains enough of the allergy-causing proteins to cause reactions.[48] Whole milk, butter and cream have high levels of saturated fat.[49][50] Butter is a good source of Vitamin A.

| Type of fat | Total fat (g) | Saturated fat (g) | Monounsaturated fat (g) | Polyunsaturated fat (g) | Smoke point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butter[51] | 80-88 | 43-48 | 15-19 | 2-3 | 150 °C (302 °F)[52] |

| Canola oil[53] | 100 | 6-7 | 62-64 | 24-26 | 205 °C (401 °F)[54][55] |

| Coconut oil[56] | 99 | 83 | 6 | 2 | 177 °C (351 °F) |

| Corn oil[57] | 100 | 13-14 | 27-29 | 52-54 | 230 °C (446 °F)[52] |

| Lard[58] | 100 | 39 | 45 | 11 | 190 °C (374 °F)[52] |

| Peanut oil[59] | 100 | 17 | 46 | 32 | 225 °C (437 °F)[52] |

| Olive oil[60] | 100 | 13-19 | 59-74 | 6-16 | 190 °C (374 °F)[52] |

| Rice bran oil | 100 | 25 | 38 | 37 | 250 °C (482 °F)[61] |

| Soybean oil[62] | 100 | 15 | 22 | 57-58 | 257 °C (495 °F)[52] |

| Suet[63] | 94 | 52 | 32 | 3 | 200 °C (392 °F) |

| Sunflower oil[64] | 100 | 10 | 20 | 66 | 225 °C (437 °F)[52] |

| Sunflower oil (high oleic) | 100 | 12 | 84[54] | 4[54] | |

| Vegetable shortening (hydrogenated)[65] | 100 | 25 | 41 | 28 | 165 °C (329 °F)[52] |

Health concerns

A 2015 study concluded that "hypercholesterolemic people should keep their consumption of butter to a minimum, whereas moderate butter intake may be considered part of the diet in the normocholesterolemic population".[66]

References

- Elert, Glenn. "Density". The Physics Hypertextbook. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "A Substitute for 'Annatto' in Butter". Nature. Nature. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- butyrum Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, on Perseus

- βούτυρον Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- butter Archived 14 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionaries

- βοῦς Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- τυρός Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- Beekes, Robert Stephen Paul, and Lucien Van Beek. Etymological dictionary of Greek. Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill, 2014

- Palaeolexicon Archived 4 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Word study tool of ancient languages

- Rolf Jost "Milk and Dairy Products" Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_589.pub3

- McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York, New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. LCCN 2004058999. OCLC 56590708.

- "Article on sweet cream, whey cream, and the butters they produce". Kosher. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Charles Thom, Walter Fisk, The Book of Cheese, 1918, reprinted in 2007 as ISBN 1429010746, p. 296

- Doane, Charles Francis (12 November 2017). "Whey butter". Washington, D.C. : U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Bureau of Animal Industry. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- "No buts, it's Rucava butter!". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. LETA. 6 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- Dates from McGee p. 10.

- Dalby p. 65.

- Bostock and Riley translation. Book 28, chapter 35.

- Galen. de aliment. facult.

- Web Exhibits: Butter. Ancient Firkins Archived 21 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- Soyer, Alexis (1977) [1853]. The Pantropheon or a History of Food and its Preparation in Ancient Times. Wisbech, Cambs.: Paddington Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-448-22976-8.

- The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.III, London (1847) Charles Knight, p.975.

- Edwards, Everett E. "Europe's Contribution to the American Dairy Industry". The Journal of Economic History, Volume 9, 1949. 72-84.

- Hunziker, O F (1920). The Butter Industry, Prepared for Factory, School and Laboratory. LaGrange, IL: author.

- Hunziker, O F; D. Fay Hosman (1 November 1917). "Tallowy Butter—its Causes and Prevention". Journal of Dairy Science. American Dairy Science Association. 1 (4): 320–346. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(17)94386-3.

- Hunziker, O F; D. Fay Hosman (1 March 1920). "Mottles in Butter—Their Causes and Prevention". Journal of Dairy Science. American Dairy Science Association. 3 (2): 77–106. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(20)94253-4.

- Hunziker, O F; W. A. Cordes; B. H. Nissen (1 September 1929). "Studies on Butter Salts". Journal of Dairy Science. American Dairy Science Association. 11 (5): 333–351. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(28)93647-4.

- Hunziker, O F; W. A. Cordes; B. H. Nissen (1 March 1929). "Metals in Dairy Equipment. Metallic Corrosion in Milk Products and its Effect on Flavor". Journal of Dairy Science. American Dairy Science Association. 12 (2): 140–181. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(29)93566-9.

- Hunziker, O F; W. A. Cordes; B. H. Nissen (1 May 1929). "Metals in Dairy Equipment: Corrosion Caused by Washing Powders, Chemical Sterilizers, and Refrigerating Brines". Journal of Dairy Science. American Dairy Science Association. 12 (3): 252–284. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(29)93575-X.

- Hunziker, O F; W. A. Cordes; B. H. Nissen (1 July 1931). "Method for Hydrogen Ion Determination of Butter". Journal of Dairy Science. American Dairy Science Association. 14 (4): 347–37. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(31)93478-4.

- Hale, Sarah Josepha Buell (1857). Mrs. Hale's new cook book.

- Web Exhibits: Butter. Eating less butter, and more fat Archived 14 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- See for example this chart Archived 8 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine from International Margarine Association of the Countries of Europe statistics Archived 30 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 December 2005.

- Parker, Milton E. (1948). "Princely Packets of Golden Health (A History of Butter Packaging)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 15 October 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "A Better Stick of Butter?". Cook's Illustrated (77): 3. November–December 2005.

- "Commercial Butter Making and Packaging Machines". Schier Company, Inc. Archived from the original on 20 May 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- Most nations produce and consume the bulk of their butter domestically.

- "Envoyé spécial". francetv info. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Statistics from USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (1999). Dairy: Word Markets and Trade Archived 23 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 December 2005. The export and import figures do not include trade between nations within the European Union, and there are inconsistencies regarding the inclusion of clarified butterfat products (explaining why New Zealand is shown exporting more butter in 1997 than was produced).

- Salopek, Paul (23 January 2018). "Here, the Homemade Butter Is Aged for Half a Century". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018.

- Crawford et al., part B, section III, ch. 1: Butter Archived 3 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 November 2005.

- Bring back butter conditioners Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 November 2005. The feature has been phased out for energy conservation reasons.

- How Long Does Butter Last? Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 03, October 2014.

- Jean-Robert Pitte, French Gastronomy: The History and Geography of a Passion, ISBN 0231124163, p. 94

- Robert Belleret, Paul Bocuse, l'épopée d'un chef, 2019, ISBN 2809825904

- Katie Armour, "Top 20 Julia Child Quotes", Matchbook, April 15, 2013

- From data here Archived 24 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine, one teaspoon of butter contains 0.03 grams of lactose; a cup of milk contains 400 times that amount.

- Allergy Society of South Africa. Milk Allergy & Intolerance Archived 26 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 November 2005.

- "Nutrition for Everyone: Basics: Saturated Fat - DNPAO - CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- Choices, NHS. "How to eat less saturated fat - Live Well - NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "Butter, stick, salted, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- The Culinary Institute of America (2011). The Professional Chef (9th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-42135-2. OCLC 707248142.

- "Oil, canola, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Nutrient database, Release 25". United States Department of Agriculture.

- Katragadda, H. R.; Fullana, A. S.; Sidhu, S.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á. A. (2010). "Emissions of volatile aldehydes from heated cooking oils". Food Chemistry. 120: 59. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.070.

- "Oil, coconut, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Oil, corn, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Lard, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Peanut oil, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Oil, olive, extra virgin, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Rice Bran Oil FAQ's". AlfaOne.ca. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "Oil, soybean, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Beef, variety meats and by-products, suet, raw, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Sunflower oil, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Shortening, vegetable, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Engel, S; Tholstrup, T (August 2015). "Butter increased total and LDL cholesterol compared with olive oil but resulted in higher HDL cholesterol compared with a habitual diet". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 102 (2): 309–15. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.112227. PMID 26135349.

Further reading

- McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York, New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. LCCN 2004058999. OCLC 56590708. pp. 33–39, "Butter and Margarine"

- Dalby, Andrew (2003). Food in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge (UK). p. 65. ISBN 0-415-23259-7. Retrieved 29 April 2020 – via Google Books.

- Michael Douma (editor). WebExhibits' Butter pages. Retrieved 21 November 2005.

- Crawford, R. J. M.; et al. (1990). The Technology of Traditional Milk Products in Developing Countries. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-102899-5. Full text online

- Grigg, David B. (7 November 1974). The Agricultural Systems of the World: An Evolutionary Approach, 196–198. Google Print. ISBN 0-521-09843-2 (accessed 28 November 2005). Also available in print from Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Butter. |

| Look up butter in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Manufacture of butter, The University of Guelph

- "Butter", Food Resource, College of Health and Human Sciences, Oregon State University, 20 February 2007. – FAQ, links, and extensive bibliography of food science articles on butter.

- Cork Butter Museum: the story of Ireland’s most important food export and the world’s largest butter market

- Virtual Museum Exhibit on Milk, Cream & Butter