Second Battle of the Aisne

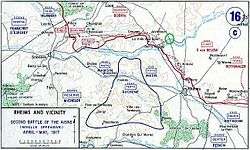

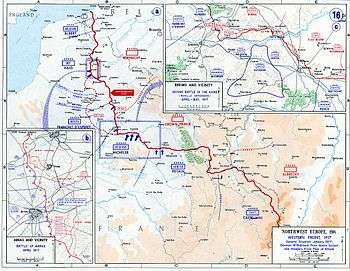

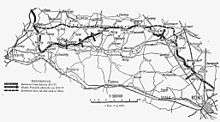

The Second Battle of the Aisne (French: Bataille du Chemin des Dames or French: Seconde bataille de l'Aisne, 16 April – mid-May 1917) was the main part of the Nivelle Offensive, a Franco-British attempt to inflict a decisive defeat on the German armies in France. The Entente strategy was to conduct offensives from north to south, beginning with an attack by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) then the main attack by two French army groups on the Aisne. General Robert Nivelle planned the offensive in December 1916, after he replaced Joseph Joffre as Commander-in-Chief of the French Army.

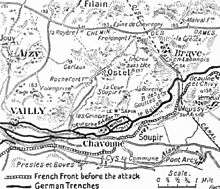

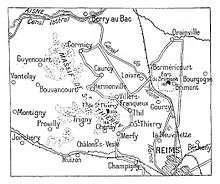

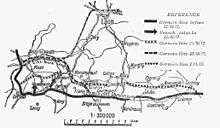

The objective of the attack on the Aisne was to capture the prominent 80-kilometre-long (50 mi), east–west ridge of the Chemin des Dames, 110 km (68 mi) north-east of Paris and then advance northwards to capture the city of Laon. When the French armies met the British advancing from the Arras front, the Germans would be pursued towards Belgium and the German frontier. The offensive began on 9 April, when the British began the Battle of Arras. On 16 April, the Groupe d'armées de Reserve (GAR, Reserve Army Group) attacked the Chemin des Dames and the next day, the Fourth Army, part of Groupe d'armées de Centre (GAC, Central Army Group), near Reims to the south-east, began the Battle of the Hills.

The Chemin des Dames ridge had been quarried for stone for centuries, leaving a warren of caves and tunnels which were used as shelters by German troops to escape the French bombardment. The offensive met massed German machine-gun and artillery fire, which inflicted many casualties and repulsed the French infantry at many points. The French achieved a substantial tactical success and took c. 29,000 prisoners but failed to defeat decisively the German armies. The failure had a traumatic effect on the morale of the French army and many divisions mutinied. Nivelle was superseded by General Philippe Pétain, who adopted a strategy of "healing and defence", to resume the wearing-out of the German Army while conserving French infantry. Pétain began a substantial programme re-equipment of the French Army, had 40–62 mutineers shot as scapegoats and provided better food, more pay and more leave, which led to a considerable improvement in morale.

The new French strategy was not one of passive defence; in June and July the Fourth, Sixth and Tenth Armies conducted several limited attacks and the First Army was sent to Flanders to participate in the Third Battle of Ypres. The British prolonged the Arras offensive into mid-May, despite uncertainty about French intentions, high losses and diminishing returns, as divisions were transferred northwards to Flanders. The British captured Messines Ridge on 7 June and spent the rest of the year on the offensive in the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July – 10 November) and the Battle of Cambrai (20 November – 8 December). The mutinies in the French armies became known in general to the Germans but the cost of the defensive success on the Aisne made it impossible to reinforce Flanders and conduct more than local operations on the Aisne and in Champagne. A French attack at Verdun in August recaptured much of the ground lost in 1916 and in the Battle of La Malmaison in October captured the west end of the Chemin des Dames and forced the Germans to withdraw to the north bank of the Ailette.

Background

Strategic developments

Nivelle believed the Germans had been exhausted by the Battle of Verdun and the Battle of the Somme in 1916 and could not resist a breakthrough offensive, which could be completed in 24–48 hours.[1] The main attack on the Aisne would be preceded by a large diversionary attack by the British Third and First armies at Arras. The French War Minister, Hubert Lyautey and Chief of Staff General Henri-Philippe Pétain opposed the plan, believing it to be premature. The British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig, supported the concept of a decisive battle but insisted that if the first two phases of the Nivelle scheme were unsuccessful, the British effort would be moved north to Flanders.[2] Nivelle threatened to resign if the offensive did not go ahead and having not lost a battle, had the enthusiastic support of the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George.[1] The French Prime Minister Aristide Briand supported Nivelle but the war minister Lyautey resigned during a dispute with the Chamber of Deputies and the Briand government fell; a new government under Alexandre Ribot took office on 20 March.[3]

The Second Battle of the Aisne involved c. 1.2 million troops and 7,000 guns on a front from Reims to Roye, with the main effort against the German positions along the Aisne river.[4] The original plan of December 1916 was plagued by delays and information leaks. By the time the offensive began in April 1917, the Germans had received intelligence of the Allied plan and strengthened their defences on the Aisne front. The German retreat to the Hindenburg Line Operation Alberich (Unternehmen Alberich) left a belt of devastated ground up to 25 mi (40 km) deep in front of the French positions facing east from Soissons, northwards to St. Quentin. Alberich freed 13–14 German divisions which were moved to the Aisne, increasing the German garrison to 38 divisions against 53 French divisions.[5] The German withdrawal forestalled the attacks of the British and Groupe d'armées du Nord (GAN) but also freed French divisions for the attack. By late March, GAN had been reduced by eleven infantry, two cavalry divisions and 50 heavy guns, which went into the French strategic reserve.[6]

Tactical developments

When Hindenburg and Ludendorff took over from Falkenhayn on 28 August 1916, the pressure being placed on the German army in France was so great that new defensive arrangements, based on the principles of depth, invisibility and immediate counter-action were formally adopted, as the only means by which the growing material strength of the French and British armies could be countered.[7] Instead of fighting the defensive battle in the front line or from shell-hole positions near it, the main fight was to take place behind the front line, out of view and out of range of enemy field artillery. Conduct of the Defensive Battle (Grundsätze für die Führung in der Abwehrschlacht) was published on 1 December 1916. The new manual laid down the organisation for the mobile defence of an area, rather than the rigid defence of a trench line. Positions necessary for the new method were defined in Principles of Field Position Construction (Allgemeines über Stellungsbau).[8]

Experience of the German First Army in the Somme Battles, (Erfahrungen der I. Armee in der Sommeschlacht) was published on 30 January 1917. Towards the end of the Battle of the Somme in 1916, Colonel Fritz von Loßberg (Chief of Staff of the 1st Army) had been able to establish a line of relief divisions (Ablösungsdivisionen). In his analysis of the battle, Loßberg opposed the granting of discretion to front trench garrisons to retire, as he believed that manoeuvre did not allow the garrisons to evade Allied artillery-fire, which could blanket the forward area and invited enemy infantry to occupy vacated areas unopposed. Loßberg considered that spontaneous withdrawals would disrupt the counter-attack reserves as they deployed and further deprive battalion and division commanders of the ability to conduct an organised defence, which the dispersal of infantry over a wider area had already made difficult. Loßberg and other officers had severe doubts as to the ability of relief divisions to arrive on the battlefield in time to conduct an immediate counter-attack (Gegenstoß) from behind the battle zone and wanted the Somme practice of fighting in the front line to be retained and authority devolved no further than the battalion, so as to maintain organizational coherence, in anticipation of a methodical counter-attack (Gegenangriff) after 24–48 hours by the relief divisions. Ludendorff was sufficiently impressed by the Loßberg memorandum to add it to the new Manual of Infantry Training for War.[9]

Prelude

German defensive preparations

Unternehmen Alberich

%2C_1917.jpg)

During the German withdrawal to the Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg Line) in March 1917, a modest withdrawal took place in the neighbourhood of Soissons. On 17 March, the German defences at Crouy and Côte 132 were found to be empty and as French troops followed up the retirement, German troops counter-attacked at Vregny and Margival, which reduced the speed of the French pursuit to a step-by-step advance. By April, the French advance had only progressed beyond Neuville-sur-Margival and Leuilly. On 1 April, a French attack along the line of the Ailette–Laon road reached the outskirts of Laffaux and Vauxaillon. Vauxeny and Vauxaillon were occupied a few days later.[10]

Defensive battle

In a new manual of 1 December 1916, Grundsätze für die Führung in der Abwehrschlacht im Stellungskrieg (Principles of Command for Defensive Battle), the policy of unyielding defence of ground regardless of its tactical value, was replaced by the defence of positions suitable for artillery observation and communication with the rear, where an attacking force would "fight itself to a standstill and use up its resources while the defenders conserve[d] their strength". Defending infantry would fight in areas, with the front divisions in an outpost zone up to 3,000 yd (2,700 m) deep behind listening posts, with the main line of resistance placed on a reverse slope, in front of artillery observation posts, which were kept far enough back to retain observation over the outpost zone. Behind the main line of resistance was a Grosskampfzone (battle zone), a second defensive area 1,500–2,500 yd (1,400–2,300 m) deep, also placed as far as possible on ground hidden from enemy observation, while in view of German artillery observers.[11] A rückwärtige Kampfzone (rear battle zone) further back was to be occupied by the reserve battalion of each regiment.[12]

Field fortification

"Principles of Field Fortification" (Allgemeines über Stellungsbau) was published in January 1917 and by April an outpost zone (Vorpostenfeld) held by sentries, had been built along the Western Front. Sentries could retreat to larger positions (Gruppennester) held by Stoßtrupps (five men and an NCO per Trupp), who would join the sentries to recapture sentry-posts by immediate counter-attack. Defensive procedures in the battle zone were similar but with greater numbers of men. The front trench system was the sentry line for the battle zone garrison, which was allowed to move away from concentrations of enemy fire and then counter-attack to recover the battle and outpost zones; such withdrawals were envisaged as occurring on small parts of the battlefield which had been made untenable by Allied artillery fire, as the prelude to Gegenstoß in der Stellung (immediate counter-attack within the position). Such a decentralised battle by large numbers of small infantry detachments would present the attacker with unforeseen obstructions. Resistance from troops equipped with automatic weapons, supported by observed artillery fire, would increase the further the advance progressed. A school was opened in January 1917 to teach infantry commanders the new methods.[13]

Given the Allies' growing superiority in munitions and manpower, attackers might still penetrate to the second (artillery protection) line, leaving in their wake German garrisons isolated in Widerstandsnester, (resistance nests, Widas) still inflicting losses and disorganisation on the attackers. As the attackers tried to capture the Widas and dig in near the German second line, Sturmbataillone and Sturmregimenter of the counter-attack divisions would advance from the rückwärtige Kampfzone into the battle zone, in an immediate counter-attack, (Gegenstoß aus der Tiefe). If the immediate counter-attack failed, the Eingreif (counter-attack) divisions would take their time to prepare a methodical attack, provided the lost ground was essential to the retention of the main position. Such methods required large numbers of reserve divisions ready to move to the battlefront. The reserve was obtained by creating 22 divisions by internal reorganisation of the army, bringing divisions from the eastern front and by shortening the western front, in Operation Alberich. By the spring of 1917, the German army in the west had a strategic reserve of 40 divisions.[14]

Battle

Third Army

Groupe d'armées du Nord (GAN) on the northern flank of Groupe d'armées de Reserve (GAR) had been reduced to the Third Army with three corps in line, by the transfer of the First Army to the GAR. The Third Army began French operations, with preliminary attacks on German observation points at St. Quentin on 1–4 and 10 April.[15][lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] Large reconnaissance forces were set towards the Dallon spur on 1 April, which were not able to gain footholds in the German front defences, although the British Fourth Army to the north captured the woods around Savy. On 2 April a bigger French attack on Dallon failed but on 3 April the Third Army attacked after a "terrific" bombardment, on a front of about 8 mi (13 km) north of a line from Castres to Essigny-le-Grand and Benay, between the Somme canal at Dallon, southwest of St Quentin and the Oise.[18]

After another attack on 4 April, the villages of Dallon, Giffecourt, Cerizy and côtes (hills) 111, 108, and 121 south of Urvillers, were captured and the German position at the apex of the triangle from Ham to St Quentin and La Fère was made vulnerable to a further attack. The French had attacked in intense cold and driving rain, with chronic supply shortages caused by the German destruction of roads and immense French traffic jams on the supply routes which had been sufficiently repaired to bear traffic.[18] East of the Oise and north of the Aisne, the Third Army took the southern and north-western outskirts of Laffaux and Vauxeny. On 4 April German counter-attacks north of the Aisne were repulsed south of Vauxeny and Laffaux. The French captured Moy on the west bank of the Oise, along with Urvillers and Grugies, a village opposite Dallon on the east bank of the Somme. North of the farm of La Folie, the Germans were pushed back and three 155 mm (6.1 in) howitzers and several Luftstreitkräfte lorries were captured. Beyond Dallon French patrols entered the south-western suburb of St. Quentin.[19]

The main attack by GAN was planned as two successive operations, an attack by XIII Corps to capture Rocourt and Moulin de Tous Vents south-west of the city, to guard the flank of the principal attack by XIII Corps and XXXV Corps on Harly and Alaincourt, intended to capture the high ground east and south-east of St. Quentin. Success would enable the French to menace the flank of the German forces to the south, along the Oise to La Fère and the rear of the German positions south of the St. Gobain massif, due to be attacked from the south by the Sixth Army of the GAR. The French were inhibited from firing on St. Quentin, which allowed the Germans unhampered observation from the cathedral and from factory chimneys and to site artillery in the suburbs, free from counter-battery fire. French attacks could only take place at night or during twilight and snow, rain, low clouds and fog made aircraft observation for the artillery impossible. German work on the Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg Line) continued but the first line, built along reverse-slopes was complete and from which flanking-fire could be brought to bear on any attack. Concrete machine-gun emplacements proved immune to all but the heaviest and most accurate howitzer-fire and the main position was protected by an observation line along the crest in front, which commanded no man's land, which was 800–1,200 yd (730–1,100 m) deep.[20]

The British Fourth Army was unable to assist the French with an attack, due to a lack of divisions after transfers north to the British Third Army but was able to assist with artillery-fire from the north and kept a cavalry division in readiness to join a pursuit. The French artillery had been reduced to c. 250 guns by transfers south to GAR, which was insufficient to bombard the German defences and conduct counter-batter fire simultaneously. On 13 April at 5:00 a.m., XIII Corps attacked with two divisions; the 26th Division on the right took the German first line and then defeated two German counter-attacks but the 25th Division on the left was repulsed almost immediately by uncut wire and machine-gun fire, despite French field artillery being advanced into no man's land at the last minute to cut the wire. Casualties in the thirteen attacking battalions were severe. The 25th Division was ordered by the army commander, General Humbert to attack again at 6:00 p.m. but the orders arrived too late and the attack did not take place. French aircraft were active over the attack front but at midday large formations of German fighters arrived and forced the French artillery-observation and reconnaissance aircraft back behind the front line. By the end of the day the 26th Division had held on to 100 yd (91 m) of the German front trench and the 25th Division had been forced back to its jumping-off trenches. German artillery-fire had not been heavy and the defence had been based on machine-gun fire and rapid counter-attacks. The XIII Corps and XXXV Corps attack due next day was eventually cancelled.[21]

Fifth and Sixth armies

The Fifth Army attacked on 16 April at 6:00 a.m., which had dawned misty and overcast. From the beginning, German machine-gunners were able to engage the French infantry and inflict many casualties, although German artillery-fire was far less destructive. Courcy on the right flank was captured by the 1st Brigade of the Russian Expeditionary Force in France but the advance was stopped at the Aisne–Marne canal. The canal was crossed further north and Berméricourt was captured against a determined German defence. From Bermericourt to the Aisne the French attack was repulsed and south of the river French infantry were forced back to their start-line. On the north bank of the Aisne the French attack was more successful, the 42nd and 69th divisions reached the German second position between the Aisne and the Miette, the advance north of Berry penetrating 2.5 mi (4.0 km).[22]

Tanks to accompany the French infantry to the third objective arrived late and the troops were too exhausted and reduced by casualties to follow them. Half of the tanks were knocked out in the German defences and then acted as pillboxes in advance of the French infantry, which helped to defeat a big German counter-attack. German infantry launched hasty counter-attacks along the front, recaptured Bermericourt and conducted organised counter-attacks where the French infantry had advanced the furthest. At Sapigneul in the XXXII Corps area, the 37th Division attack failed, which released German artillery in the area to fire in enfilade into the flanks of the adjacent divisions, which had been able to advance and the guns were also able to engage the French tanks north of the Aisne. The defeat of the 37th Division restored the German defences between Loivre and Juvincourt.[23]

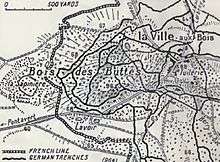

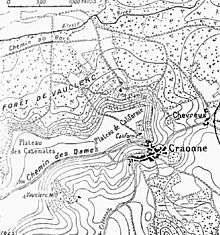

The left flank division of the XXXII Corps and the right division of the V Corps penetrated the German second position south of Juvincourt but French tanks attacking south of the Miette from Bois de Beau Marais advanced to disaster. German observers at Craonne, on the east end of the Chemin des Dames, were able to direct artillery-fire against the tanks and 23 were destroyed behind the French front line; few of the tanks reached the German defences and by the evening only ten tanks were operational.[lower-alpha 3] On the left flank, V Corps was stopped at the Bois des Boches and the hamlet of la Ville aux Bois. On the Chemin des Dames, I Corps made very little progress and by evening had advanced no further than the German support line, 200–300 yd (180–270 m) ahead. The French infantry had suffered many casualties and few of the leading divisions were capable of resuming the attack. The advance had failed to reach objectives which were to have fallen by 9:30 a.m. but 7,000 German prisoners had been taken.[25]

The attack on the right flank of the Sixth Army, which faced north between Oulches and Missy, took place from Oulches to Soupir and had less success than the Fifth Army; the II Colonial Corps advanced for 0.5 mi (0.80 km) in the first thirty minutes and was then stopped. The XX Corps attack from Vendresse to the Oise–Aisne Canal had more success, the 153rd Division on the right flank reached the Chemin des Dames south of Courtecon after a second attack, managing an advance of 1.25 mi (2.01 km). The VI Corps advanced its right flank west of the Oise–Aisne Canal but its left flank was held up. On the east-facing northern flank near Laffaux, I Colonial Corps was able to penetrate only a few hundred yards into the defences of the Condé-Riegel (Condé Switch trench) and failed to take Moisy Farm plateau. Laffaux was captured and then lost to a counter-attack before changing hands several times, until finally captured on 19 April.[10] To the east of Vauxaillon, at the north end of the Sixth Army, Mont des Singes was captured with the help of British heavy artillery but then lost to a German counter-attack. The Sixth Army operations took c. 3,500 prisoners but no break-through had been achieved but the German second position been reached at only one point.[26]

On the second day, Nivelle ordered the Fifth Army to attack north-eastwards to reinforce success, believing that the Germans intended to hold the ground in front of the Sixth Army. The Fifth Army was not able substantially to advance on 17 April but the Sixth Army, which had continued to attack overnight, forced a German withdrawal from the area of Braye, Condé and Laffaux to the Siegfriedstellung, which ran from Laffaux Mill to the Chemin des Dames and joined the original defences at Courtecon. The German retirement was carried out in a rush and many guns were left behind, along with "vast" stocks of munitions. The French infantry reached the new German positions with an advance of 4 mi (6.4 km).[27]

Fourth Army

On 17 April the Fourth Army on the left of Groupe d'armées de Centre (GAC) began the subsidiary attack in Champagne from Aubérive to the east of Reims which became known as Bataille des Monts, with the VIII, XVII and XII Corps on an 11 km (6.8 mi) front.[28] The attack began at 4:45 a.m. in cold rain alternating with snow showers. The right flank guard to the east of Suippes was established by the 24th Division and Aubérive on the east bank of the river and the 34th Division took Mont Cornillet and Mont Blond. The "Monts" were held against a German counter-attack on 19 April by the 5th, 6th (Eingreif divisions) and the 23rd division and one regiment between Nauroy and Moronvilliers.[29] On the west bank the Moroccan Division was repulsed on the right and captured Mont sans Nom on the left. To the north-east of the hill the advance reached a depth of 1.5 mi (2.4 km) and next day the advance was pressed beyond Mont Haut. The Fourth Army attacks took 3,550 prisoners and 27 guns.[27] German attacks on 27 May had temporary success before French counter-attacks recaptured the ground around Mont Haut; lack of troops had forced the Germans into piecemeal attacks instead of a simultaneous attack along the whole front.[30]

Tenth Army

Nivelle ordered the Tenth Army forward between the Fifth and Sixth armies on 21 April. The IX Corps and XVIII Corps took over between Craonne and Hurtebise and local operations were continued on the fronts of the Fourth and Fifth armies with little success. An attack on Brimont on (4–5 May), the capture of which would have been of great tactical value, was postponed on the orders of the French government and never took place. The Tenth Army captured the Californie plateau on the Chemin des Dames, the Sixth Army captured the Siegfriedstellung for 2.5 mi (4.0 km) along the Chemin des Dames and then advanced at the salient opposite Laffaux. An attack on 5 May southeast of Vauxaillon took Moisy Farm and Laffaux Mill and repulsed German counter-attacks. Next day another advance was conducted north of the mill. German counter-attacks continued in constant attack and counter-attack in the Soissons sector.[10] By the end of 5 May the Sixth Army had reached the outskirts of Allemant and taken c. 4,000 prisoners. The offensive continued on the Fourth Army front where Mont Cornillet was captured and by 10 May 28,500 prisoners and 187 guns had been taken by the French armies.[31]

German 7th Army counter-attacks

Between Vauxaillon and Reims and on the Moronvilliers heights the French had captured much of the German defensive zone, despite the failure to break through and Army Group German Crown Prince counter-attacked before the French could consolidate, mostly by night towards the summits of the Chemin des Dames and the Moronvilliers massif. During the nights of the 6/7 and 7/8 May, the Germans attacked from Vauxaillon to Craonne and on the night of 8/9 May German attacks were repulsed at Cerny, La Bovelle, Heutebise Farm and the Californie Plateau. Next day, German counter-attacks on Chevreux, north-east of Craonne at the foot of the east end of the Chemin des Dames were defeated. More attacks on the night of 9/10 May were defeated by the French artillery and machine-gun fire; the French managed to advance on the northern slopes of the Vauclerc Plateau. On 10 May, another German attack at Chevreux was defeated and the French advanced north of Sancy and on the night of 10/11 May, and the following day, German attacks were repulsed on the Californie Plateau and at Cerny.[32]

On 16 May, a German counter-offensive, on a front of 2.5 mi (4.0 km) from the north-west of Laffaux Mill to the Soissons–Laon railway, was defeated and after dark more attacks north of Laffaux Mill and north-west of Braye-en-Laonnois also failed. French attacks on 17 May took ground east of Craonne and on 18 May, German attacks on the Californie Plateau and on the Chemin des Dames just west of the Oise–Aisne Canal, were repulsed. On 20 May, a counter-offensive to retake the French positions from Craonne to the east of Fort de la Malmaison, was mostly defeated by artillery-fire and where German infantry were able to advance through the French defensive barrages, French infantry easily forced them back; 1,000 unwounded prisoners were taken.[33] On 21 May, German surprise attacks on the Vauclerc Plateau failed and on the following evening, the French captured several of the remaining observation posts dominating the Ailette Valley and three German trench lines east of Chevreux. A German counter-attack on the Californie Plateau was smashed by artillery and infantry small-arms fire and 350 prisoners taken.[33]

Battle of the Observatories

At 8:30 p.m. on 23 May, a German assault on the Vauclerc Plateau was defeated and on 24 May, a renewed attack was driven back in confusion.[33] During the night the French took the wood south-east of Chevreux and almost annihilated two German battalions. On 25 May, three German columns attacked a salient north-west of Bray-en-Laonnois and gained a footing in the French first trench, before being forced out by a counter-attack. On 26 May German attacks on salients east and west of Cerny were repulsed and from 26–27 May, German attacks between Vauxaillon and Laffaux Mill broke down. Two attacks on 28 May at Hurtebise were defeated by French artillery-fire and on the night of 31 May – 1 June and attacks by the Germans west of Cerny also failed. On the morning of 1 June, after a heavy bombardment, German troops captured several trenches north of Laffaux Mill and lost them to counter-attacks in the afternoon. On 2 June a bigger German attack began, after an intensive bombardment of the French front, from the north of Laffaux to the east of Berry-au-Bac. On the night of 2/3 June, two German divisions made five attacks on the east, west and central parts of the Californie Plateau and the west end of the Vauclerc Plateau. The Germans attacked in waves, at certain points advancing shoulder-to-shoulder, supported by flame-thrower detachments and gained some ground on the Vauclerc Plateau, until French counter-attacks recovered the ground. Despite the French holding improvised defences and the huge volumes of German artillery-fire used to prepare attacks, the German organised counter-attacks (Gegenangriffe) met with little success and at Chevreux north-east of Craonne, the French had even pushed further into the Laon Plain.[34]

Aftermath

Analysis

In 2015, Uffindell wrote that retrospective naming and dating of events can affect the way in which the past is understood. The Second Battle of the Aisne began on 16 April but the duration and extent of the battle have been interpreted differently. The ending of the battle is usually given as mid-May. Uffindell called this politically convenient, since this excluded the Battle of La Malmaison in October, making it easier to blame Nivelle. Uffindel wrote that the exclusion of La Malmaison was artificial, since the attack was begun from the ground taken from April to May. General Franchet d'Espèrey called La Malmaison "the decisive phase of the Battle...that began on 16 April and ended on 2 November....".[35]

The offensive advanced the front line by 6–7 km (3.7–4.3 mi) on the front of the Sixth Army, which took 5,300 prisoners and a large amount of equipment.[36] The operation had been planned as a decisive blow to the Germans; by 20 April it was clear that the strategic intent of the offensive had not been achieved and by 25 April most of the fighting had ended. Casualties had reached 20 percent in the French armies by 10 May and some divisions suffered more than 60 percent losses. On 3 May, the French 2nd Division refused orders, similar refusals and mutiny spread through the armies; the Nivelle Offensive was abandoned in confusion on 9 May.[37] The politicians and public were stunned by the chain of events and on 16 May, Nivelle was sacked and moved to North Africa. He was replaced by the considerably more cautious Pétain with Foch as chief of the General Staff, who adopted a strategy of "healing and defence" to avoid casualties and to restore morale.[38] Pétain had 40–62 mutineers shot as examples and introduced reforms to improve the welfare of French troops, which did much to restore morale.[39]

The operations in Champagne on 20 May ended the Nivelle Offensive; most of the Chemin-des-Dames plateau, particularly the east end, which dominated the plain north of the Aisne had been captured. Bois-des-Buttes, Ville-aux-Bois, Bois-des-Boches and the German first and second positions from there to the Aisne had also been captured. South of the river, the Fifth and Tenth armies on the plain near Loivre, had managed to advance west of the Brimont Heights. East of Reims the Fourth Army had captured most of the Moronvilliers massif and Auberive, then advanced along the Suippe, which provided good jumping-off positions for a new offensive. The cost of the Nivelle Offensive in casualties and loss of morale were great but German losses were also high and the tactical success of the French in capturing elaborately fortified positions and defeating counter-attacks, reduced German morale. The Germans had been forced out of three of the most elaborately fortified positions on the Western Front and failed to recapture them. Vimy Ridge, the Scarpe Heights, the caverns, spurs and plateau of the Chemin des Dames and the Moronvilliers massif had been occupied for more than two years, carefully surveyed by German engineers and fortified to make them impregnable. In six weeks all were lost and the Germans were left clinging to the eastern or northern edges of the ridges of the summits.[40]

_nach_den_April-Angriffen_1917.jpg)

The French tactic of assault brutal et continu suited the German defensive dispositions, since much of the new construction had taken place on reverse slopes. The speed of attack and the depth of the French objectives meant that there was no time to establish artillery observation posts overlooking the Ailette valley, in the areas where French infantry had reached the ridge. The tunnels and caves under the ridge nullified the destructive effect of the French artillery, which was also reduced by poor weather and by German air superiority, which made French artillery-observation aircraft even less effective. The rear edge of the German battle zone along the ridge had been reinforced with machine-gun posts and the German divisional commanders decided to hold the front line, rather than giving ground elastically; few of the Eingreif Divisions were needed to intervene in the battle. [41]

Casualties

In 1939 Wynne wrote that the French lost 117,000 casualties including 32,000 killed in the first few days but that the effect on military and civilian morale was worse than the casualties.[42] In the 1939 volume of Der Weltkrieg, the German official historians recorded German losses to the end of June as 163,000 men including 37,000 missing and claimed French casualties of 250,000–300,000 men, including 10,500 taken prisoner.[43] In 1962, G. W. L. Nicholson the Canadian Official Historian, recorded German losses of c. 163,000 and French casualties of 187,000 men.[44] A 2003 web publication gave 108,000 French casualties, 49,526 in the Fifth Army, 30,296 casualties in the Sixth Army, 4,849 in the Tenth Army, 2,169 in the Fourth Army and 1,486 in the Third Army.[45] In 2005, Doughty quoted figures of 134,000 French casualties on the Aisne from 16–25 April, of whom 30,000 men were killed, 100,000 were wounded and 4,000 were taken prisoner; the rate of casualties was the worst since November 1914. From 16 April – 10 May the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Tenth armies took 28,500 prisoners and 187 guns. The advance of the Sixth Army was one of the largest made by a French army since trench warfare began.[46]

Subsequent operations

The Battle of La Malmaison (Bataille de la Malmaison) (23–27 October) led to the capture of the village and fort of La Malmaison and control of the Chemin des Dames ridge. The 7th Army commander Boehn, was not able to establish a defence in depth along the Chemin-de-Dames, because the ridge was a hog's back and the only alternative was to retire north of the Canal de l'Oise à l'Aisne. The German artillery was outnumbered about 3:1 and on the front of the 14th Division 32 German batteries were bombarded by 125 French artillery batteries. Much of the German artillery was silenced before the French attack. Gas bombardments in the Ailette valley became so dense that the carriage of ammunition and supplies to the front was made impossible.[47]

From 24–25 October the XXI and XIV corps advanced rapidly and the I Cavalry Corps was brought forward into the XIV Corps area, in case the Germans collapsed. On 25 October the French captured the village and forest of Pinon and closed up to the line of the Canal de l'Oise à l'Aisne.[48] In four days the attack had advanced 6 mi (9.7 km) and forced the Germans from the narrow plateau of the Chemin des Dames, back to the north bank of the Ailette Valley. The French took 11,157 prisoners, 200 guns and 220 heavy mortars. French losses were 2,241 men killed, 8,162 wounded and 1,460 missing from 23–26 October, 10 percent of the casualties of the attacks during the Nivelle Offensive.[49]

Notes

- GAN under Franchet D'Esperey controlled the Third Army (General Georges Humbert) in the south XXXIII Corps had: 77th and 70th divisions from Coucy le Chateau to the Oise, just south of La Fere, XXXV Corps in the centre: 53rd, 61st and 121st divisions, from the Oise to the vicinity of Urvillers and XIII Corps on the left: 26th and 25th divisions from near Urvillers, to the boundary with the British Fourth Army at Savy. The XIV Corps was in reserve around Chauny.[16]

- Caution is suggested with the source Prelude to Victory (1939) due to certain egregiously racist passages.[17]

- The tank crews had 128 casualties in a complement of 720 men, 76 tanks were knocked out, 57 being set on fire and attached infantry had 40 percent losses.[24]

Footnotes

- Strachan 2003, p. 243.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 327–328.

- Doughty 2005, p. 337.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 326–327.

- Falls 1992, p. 492.

- Falls 1992, p. 486.

- Samuels 1995, p. 180.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 148–149.

- Wynne 1976, p. 161.

- Michelin 1919a, p. 6.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 149–151.

- Samuels 1995, p. 181.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 152–156.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 156–158.

- Falls 1992, p. 485.

- Spears 1939, p. 452.

- Spears 1939, pp. 263–265, passim.

- Spears 1939, pp. 287–290.

- The Times 1917, pp. 379–380.

- Spears 1939, pp. 453–454.

- Spears 1939, pp. 454–455.

- Falls 1992, pp. 494–495.

- Falls 1992, p. 495.

- Lahaie 2015, pp. 72–73.

- Falls 1992, pp. 495–496.

- Falls 1992, pp. 496–497.

- Falls 1992, pp. 497–498.

- Michelin 1919, p. 12.

- Balck 2008, p. 99.

- Balck 2008, pp. 99–100.

- Falls 1992, pp. 500–501.

- The Times 1918, p. 103.

- The Times 1918, p. 104.

- The Times 1918, p. 105.

- Uffindell 2015, p. 17.

- Doughty 2005, p. 351.

- Strachan 2003, p. 247.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 354, 359–360.

- Doughty 2005, p. 368.

- The Times 1918, pp. 101–102.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 187–188.

- Wynne 1976, p. 188.

- Reichsarchiv 2012, p. 410.

- Nicholson 1962, p. 243.

- Anon 2003.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 353–354.

- Balck 2008, p. 101.

- Michelin 1919a, pp. 6–7.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 384–389.

References

Books

- Balck, W. (2008) [1922]. Entwickelung der Taktik im Weltkriege [Development of Tactics in the World War] (Kessinger repr. ed.). Berlin: Eisenschmidt. ISBN 978-1-4368-2099-8.

- Die Kriegsführung im Frühjahr 1917 [War Command in Spring, 1917]. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande [The World War 1914–1918: Military Operations on Land]. XII (online ed.). Berlin: Mittler. 2012 [1939]. OCLC 248903245. Retrieved 25 November 2013 – via Die digitale Landesbibliotek Oberösterreich.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Falls, C. (1992) [1940]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-180-0.

- Lahaie, O. (2015). "3 The Development of French Tank Warfare on the Western Front, 1916–1918". In Searle, A. (ed.). Genesis, Employment, Aftermath: First World War Tanks and the New Warfare, 1900–1945. Modern Military History. number 1. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-909982-22-2.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1962). Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 59609928. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Rheims and the Battles for its Possession. Clermont Ferrand: Michelin & cie. 1920 [1919]. OCLC 5361169. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- Samuels, M. (1995). Command or Control? Command, Training and Tactics in the British and German Armies 1888–1918. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-4214-7.

- Soissons Before and During the War (English ed.). Clermont Ferrand: Michelin & cie. 1919. OCLC 470759519. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- Spears, Sir Edward (1939). Prelude to Victory (online ed.). London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 459267081. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- Strachan, H. (2003). The First World War: To Arms. I. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-1-4352-9266-6.

- Uffindell, A. (2015). The Nivelle Offensive and the Battle of the Aisne 1917: A Battlefield Guide to the Chemin des Dames. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78303-034-7.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (repr. ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

Encyclopaedias

- The Times History of the War. XII (online ed.). London: The Times. 1914–1921. OCLC 475617679. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- The Times History of the War. XIV (online ed.). London: The Times. 1914–1921. OCLC 70406275. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

Websites

- "Les Offensives d'avril 1917". chtimiste.com. France. 2003. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

Further reading

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-166-4.

- Keegan, J. (1999). The First World War. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-40052-0.

- Sheldon, J. (2015). The German Army in the Spring Offensives 1917: Arras, Aisne & Champagne. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78346-345-9.

- Simkins, P.; Jukes, G.; Hickey, M. (2003). The First World War: The War to End All Wars. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-738-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of the Aisne (1917). |

- Chemin des Dames Portail official portal, multi-language

- Chemin des Dames Virtual Memorial searchable databases soldiers, regiments, battles, cemeteries, monuments and documents

- La Caverne du Dragon museum of the 1917 battle at Chemin des Dames multimedia

- First World War: Chemin des Dames photos and descriptions, Chemin des Dames sites