Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 (Hungarian: 1848–49-es forradalom és szabadságharc, "1848–49 Revolution and War of independence") was one of many European Revolutions of 1848 and closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas. Being one of the most determinative events in Hungary's modern history, it is also one of the cornerstones of the Hungarian national identity. The crucial turning point of the events were the April laws which were ratified by King Ferdinand I, however the new young Austrian monarch Franz Joseph I arbitrarily revoked the laws without any legal competence. This unconstitutional act irreversibly escalated the conflict between the Hungarian parliament and Franz Joseph. The new constrained Stadion Constitution of Austria, the revocation of the April laws and the Austrian military campaign against the Kingdom of Hungary resulted in the fall of the pacifist Batthyány government (who sought agreement with the court) and led to the sudden emergence of Lajos Kossuth's followers in the parliament, who demanded the full independence of Hungary. The Austrian military intervention in the Kingdom of Hungary resulted in strong anti-Habsburg sentiment among Hungarians, thus the events in Hungary grew into a war for total independence from the Habsburg dynasty.

| Hungarian Revolution of 1848 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Revolutions of 1848 | |||||||

Artist Mihály Zichy's painting of Sándor Petőfi reciting the National Poem to a crowd on 15 March 1848 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

(April–August 1849) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

170,000 men from the Austrian Empire, and 200,000 men from the Russian Empire [2] | Beginning of 1849: 170,000 men[3] | ||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early history

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

After a series of serious Austrian defeats in 1849, the Austrian Empire came close to the brink of collapse. The young emperor Franz Joseph I had to call for Russian help in the name of the Holy Alliance.[4] Tsar Nicholas I answered, and sent a 200,000 strong army with 80,000 auxiliary forces. Finally, the joint army of Russian and Austrian forces defeated the Hungarian forces. After the restoration of Habsburg power, Hungary was placed under brutal martial law.[5]

The anniversary of the Revolution's outbreak, 15 March, is one of Hungary's three national holidays.

Hungary before the Revolution

The Kingdom of Hungary had always maintained a separate legal system and separate parliament, the Diet of Hungary, even after the Austrian Empire was created in 1804.[6] Unlike other Habsburg ruled areas, the Kingdom of Hungary had an old historic constitution,[7] which had limited the power of the Crown and greatly increased the authority of the parliament since the 13th century.

The administration and government of the Kingdom of Hungary (until 1848) remained largely untouched by the government structure of the overarching Austrian Empire. Hungary's central government structures remained well separated from the imperial government. The country was governed by the Council of Lieutenancy of Hungary (the Gubernium) - located in Pozsony and later in Pest - and by the Hungarian Royal Court Chancellery in Vienna.[8]

While in most Western European countries (like France and England) the king's reign began immediately upon the death of his predecessor, in Hungary the coronation was absolutely indispensable as, if it were not properly executed, the Kingdom stayed "orphaned". Even during the long personal union between the Kingdom of Hungary and other Habsburg ruled areas, the Habsburg monarchs had to be crowned as King of Hungary in order to promulgate laws there or exercise royal prerogatives in the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary.[9][10][11] Since the Golden Bull of 1222, all Hungarian monarchs were obliged to take a coronation oath during the coronation ceremony, where the new monarch had to agree to uphold the constitutional arrangement of the country, to preserve the liberties of its subjects and the territorial integrity of the realm.[12]

From 1526 to 1851, the Kingdom of Hungary maintained its own customs borders, which separated Hungary from the united customs system of other Habsburg ruled territories.

The Hungarian Jacobin Club

After the death of the Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph II, in February 1790, enlightened reforms in Hungary ceased, which outraged many reform-oriented francophone intellectuals who were followers of new radical ideas based on French philosophy and enlightenment. Ignác Martinovics worked as a secret agent for the new Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold II, until 1792. In his Oratio pro Leopoldo II, he explicitly declares that only authority derived from a social contract should be recognized; he saw the aristocracy as the enemy of mankind, because they prevented people from becoming educated. In another of his works, Catechism of People and Citizens, he argued that citizens tend to oppose any repression and that sovereignty resides with the people. He also became a Freemason, and was in favour of the adoption of a federal republic in Hungary. As a member of the Hungarian Jacobins, he was considered an idealistic forerunner of revolutionary thought by some, and an unscrupulous adventurer by others. He was in charge of stirring up a revolt against the nobility among the Hungarian serfs. For these subversive acts, Francis II, the Holy Roman Emperor, dismissed Martinovics and his boss, Ferenc Gotthardi, the former chief of the secret police. He was executed, together with six other prominent Jacobins, in May 1795. More than 42 members of the republican secret society were arrested, including the poet János Batsányi and linguist Ferenc Kazinczy[13][14][15][16][17]

Though the Hungarian Jacobin republican movement did not affect the policy of the Hungarian Parliament and the parliamentary parties, it had strong ideological ties with the extra-parliamentary forces: the radical youths and students like the poet Sándor Petőfi, the philosopher and historian Pál Vasvári and the novel-writer Mór Jókai, who sparked the revolution in the Pilvax coffee house on 15 March 1848.[18]

Era of Reforms

The Diet of Hungary had not convened since 1811.[19]

The frequent diets held in the earlier part of the reign occupied themselves with little else but war subsidies; after 1811 they ceased to be summoned. In the latter years of Francis I the dark shadow of Metternich's policy of "stability" fell across the kingdom, and the forces of reactionary absolutism were everywhere supreme. But beneath the surface a strong popular current was beginning to run in a contrary direction. Hungarian society, affected by western Liberalism, but without any direct help from abroad, was preparing for the future emancipation. Writers, savants, poets, artists, noble and plebeian, layman and cleric, without any previous concert, or obvious connection, were working towards that ideal of political liberty which was to unite all the Magyars. Mihály Vörösmarty, Ferenc Kölcsey, Ferencz Kazinczy and his associates, to mention but a few of many great names, were, consciously or unconsciously, as the representatives of the renascent national literature, accomplishing a political mission, and their pens proved no less efficacious than the swords of their ancestors.[20]

In 1825 Emperor Francis II convened the Diet in response to growing concerns amongst the Hungarian nobility about taxes and the diminishing economy, after the Napoleonic wars. This – and the reaction to the reforms of Joseph II – started what is known as the Reform Period (Hungarian: reformkor). But the Nobles still retained their privileges of paying no taxes and not giving the vote to the masses.

The influential Hungarian politician Count István Széchenyi recognized the need to bring the country the advances of the more developed West European countries, such as England.

It was a direct attack upon the constitution which, to use the words of István Széchenyi, first "startled the nation out of its sickly drowsiness". In 1823, when the reactionary powers were considering joint action to suppress the revolution in Spain, the government, without consulting the diet, imposed a war-tax and called out the recruits. The county assemblies instantly protested against this illegal act, and Francis I was obliged, at the diet of 1823, to repudiate the action of his ministers. But the estates felt that the maintenance of their liberties demanded more substantial guarantees than the dead letter of ancient laws. Széchenyi, who had resided abroad and studied Western institutions, was the recognized leader of all those who wished to create a new Hungary out of the old. For years he and his friends educated public opinion by issuing innumerable pamphlets in which the new Liberalism was eloquently expounded. In particular Széchenyi insisted that the people must not look exclusively to the government, or even to the diet, for the necessary reforms. Society itself must take the initiative by breaking down the barriers of class exclusiveness and reviving a healthy public spirit. The effect of this teaching was manifest at the diet of 1832, when the Liberals in the Lower Chamber had a large majority, prominent among whom were Ferenc Deák and Ödön Beothy. In the Upper House, however, the magnates united with the government to form a conservative party obstinately opposed to any project of reform, which frustrated all the efforts of the Liberals.[20]

The new rising political star of the mid 1830s was Lajos Kossuth, who started to rival with the popularity of Széchenyi due to his talent as orator in the liberal fraction of the parliament. Kossuth called for broader parliamentary democracy, rapid industrialization, general taxation, economic expansion through exports, and the abolition of serfdom and aristocratic privileges (equality before the law). The alarm of the government at the power and popularity of the Liberal party induced it, soon after the accession of the new king, the emperor Ferdinand I (1835–1848), to attempt to crush the reform movement by arresting and imprisoning the most active agitators among them, Lajos Kossuth and Miklós Wesselényi. But the nation was no longer to be cowed. The diet of 1839 refused to proceed to business till the political prisoners had been released, and, while in the Lower Chamber the reforming majority was larger than ever, a Liberal party was now also formed in the Upper House under the leadership of Count Louis Batthyány and Baron Joseph Eotvos. From 1000AD up to 1844, Latin language was the official language of administration, legislation and schooling in the Kingdom of Hungary. Two progressive measures of the highest importance were passed by this diet, one making Magyar the official language of Hungary, the other freeing the peasants' holdings from all feudal obligations.[20]

The results of the diet of 1839 did not satisfy the advanced Liberals, while the opposition of the government and of the Upper House still further embittered the general discontent. The chief exponent of this temper was the Pesti Hirlap, Hungary's first political newspaper, founded in 1841 by Kossuth, whose articles, advocating armed reprisals if necessary, inflamed the extremists but alienated Széchenyi, who openly attacked Kossuth's opinions. The polemic on both sides was violent; but, as usual, the extreme views prevailed, and on the assembling of the diet of 1843 Kossuth was more popular than ever, while the influence of Széchenyi had sensibly declined. The tone of this diet was passionate, and the government was fiercely attacked for interfering with the elections. A new party called as Opposition party was created, which united the reform oriented Liberals, to oppose the conservatives. Fresh triumphs were won by the Liberals (the Opposition Party). Magyar was now declared to be the language of the schools and the law-courts as well as of the legislature; mixed marriages were legalized; and official positions were thrown open to non-nobles.[20]

"Long debate" of reformers in the press (1841–1848)

The interval between the diet of 1843 and that of 1847 saw a complete disintegration and transformation of the various political parties. Széchenyi openly joined the government, while the moderate Liberals separated from the extremists and formed a new party, the Centralists.

In his 1841 pamphlet People of the East (Kelet Népe), Count Széchenyi analyzed Kossuth's policy and responded to Kossuth's reform proposals. Széchenyi believed that economic, political and social reforms should proceed slowly and with care, in order to avoid the potentially disastrous prospect of violent interference from the Habsburg dynasty. Széchenyi was aware of the spread of Kossuth's ideas in Hungarian society, which he took to overlook the need for a good relationship with the Habsburg dynasty.

Kossuth, for his part, rejected the role of the aristocracy, and questioned established norms of social status. In contrast to Széchenyi, Kossuth believed that in the process of social reform it would be impossible to restrain civil society in a passive role. He warned against attempting to exclude wider social movements from political life, and supported democracy, rejecting the primacy of elites and the government. In 1885, he labeled Széchenyi a liberal elitist aristocrat, while Széchenyi considered Kossuth to be a democrat.[21]

Széchenyi was an isolationist politician, while Kossuth saw strong relations and collaboration with international liberal and progressive movements as essential for the success of liberty.[22]

Széchenyi based his economic policy on the laissez-faire principles practiced by the British Empire, while Kossuth supported protective tariffs due to the comparatively weak Hungarian industrial sector. While Kossuth envisioned the construction of a rapidly industrialized country, Széchenyi wanted to preserve the traditionally strong agricultural sector as the main characteristic of the economy.[23]

"The Twelve Points" of the reformers

The conservatives - who usually opposed most of the reforms - could maintain a slim majority in the old feudal parliament, as the reformer liberals were divided between the ideas of Széchenyi and Kossuth.

Immediately before the elections, however, Deák succeeded in reuniting all the Liberals on the common platform of "The Twelve Points".[20]

- Freedom of the Press (The abolition of censure and the censor's offices)

- Accountable ministries in Buda and Pest (Instead of the simple royal appointment of ministers, all ministers and the government must be elected and dismissed by the parliament)

- An annual parliamentary session in Pest. (instead of the rare ad-hoc sessions which was convoked by the king)

- Civil and religious equality before the law. (The abolition of separate laws for the common people and nobility, the abolition of the legal privileges of nobility. Full religious liberty instead of moderated tolerance: the abolition of (Catholic) state religion)

- National Guard. (The forming of their own Hungarian national guard, it worked like a police force to keep the law and order during the transition of the system, thus preserving the morality of the revolution)

- Joint share of tax burdens. (abolition of the tax exemption of the nobility, the abolition of customs and tariff exemption of the nobility)

- The abolition of socage. (abolition of Feudalism and abolition of the serfdom of peasantry and their bondservices)

- Juries and representation on an equal basis. (The common people can be elected as juries at the legal courts, all people can be officials even on the highest levels of the public administration and judicature, if they have the prescribed education)

- National Bank.

- The army to swear to support the constitution, our soldiers should not be sent abroad, and foreign soldiers should leave our country.

- The freeing of political prisoners.

- Union. (With Transylvania)

The ensuing parliamentary elections resulted in a complete victory for the Progressives. This was also the last election which was based on the parliamentary system of the old feudal estates. All efforts to bring about an understanding between the government and the opposition were fruitless. Kossuth demanded not merely the redress of actual grievances, but a liberal reform which would make grievances impossible in the future. In the highest circles a dissolution of the diet now seemed to be the sole remedy; but, before it could be carried out, tidings of the February revolution in Paris reached Pressburg on the 1st of March, and on the 3rd of March Kossuth's motion for the appointment of an independent, responsible ministry was accepted by the Lower House. The moderates, alarmed not so much by the motion itself as by its tone, again tried to intervene; but on the 13th of March the Vienna revolution broke out, and the Emperor, yielding to pressure or panic, appointed Count Louis Batthyány premier of the first Hungarian responsible ministry, which included Kossuth, Széchenyi and Deák.[20]

The bloodless revolution in Pest

The crisis came from abroad - as Kossuth expected - and he used it to the full. On 3 March 1848, shortly after the news of the revolution in Paris had arrived, in a speech of surpassing power he demanded parliamentary government for Hungary and constitutional government for the rest of Austria. He appealed to the hope of the Habsburgs, "our beloved Archduke Franz Joseph" (then seventeen years old), to perpetuate the ancient glory of the dynasty by meeting half-way the aspirations of a free people. He at once became the leader of the European revolution; his speech was read aloud in the streets of Vienna to the mob by which Metternich was overthrown (13 March), and when a deputation from the Diet visited Vienna to receive the assent of Emperor Ferdinand to their petition it was Kossuth who received the chief ovation. The arrival of the news of the revolution in Paris, and Kossuth's German speech about freedom and human rights had whipped up the passions of Austrian crowd in Vienna on March 13.[25] While Viennese masses celebrated Kossuth as their hero, revolution broke out in Buda on 15 March; Kossuth traveled home immediately.[26]

The revolution started in the Pilvax coffee palace at Pest, which was a favourite meeting point of the young extra-parliamentary radical liberal intellectuals in the 1840s. On the morning of March 15, 1848, revolutionaries marched around the city of Pest, reading Sándor Petőfi's Nemzeti dal (National Song) and the 12 points (the twelve demands of theirs) to the crowd (which swelled to thousands). Declaring an end to all forms of censorship, they visited the printing presses of Landerer and Heckenast and printed Petőfi's poem together with the demands. A mass demonstration was held in front of the newly built National Museum, after which the group left for the Buda Chancellery (the Office of the Governor-General) on the other bank of the Danube.

The bloodless mass demonstrations in Pest and Buda forced the Imperial governor to accept all twelve of their demands.

Austria had its own problems with the revolution in Vienna that year, and it initially acknowledged Hungary's government. Therefore, the Governor-General's officers, acting in the name of the King appointed Hungary's new parliament with Lajos Batthyány as its first Prime Minister. The Austrian monarchy also made other concessions to subdue the Vienna masses: on 13 March 1848, Prince Klemens von Metternich was made to resign his position as the Austrian Government's Chancellor. He then fled to London for his own safety.

Parliamentary monarchy, the Batthyány government

On 17 March 1848 the Emperor assented and Batthyány created the first Hungarian responsible government. On 23 March 1848, as head of government, Batthyány commended his government to the Diet.

The first responsible government was formed:

| Prime Minister: Lajos Batthyány |

| Minister of the Interior: Bertalan Szemere |

| Finance minister: Lajos Kossuth |

| Minister of Justice: Ferenc Deák |

| Minister of Defense: Lázár Mészáros |

| Minister of Agriculture, Industry, and Trade: Gábor Klauzál |

| Minister of Labour, Infrastructure, and Transport: István Széchenyi |

| Minister of Education, Science, and Culture: József Eötvös |

| Minister besides the King (roughly Foreign Minister): Pál Antal Esterházy |

With the exception of Lajos Kossuth, all members of the government were the supporters of Széchenyi's ideas.

The Twelve Points, or the March Laws as they were now called, were then adopted by the legislature and received royal assent on 10 April. Hungary had, to all intents and purposes, become an independent state bound to Austria only by the Austrian Archduke as Palatine.[20] The new government approved a sweeping reform package, referred to as the "April laws", which created a democratic political system.[27] The newly established government also demanded that the Habsburg Empire spend all taxes they received from Hungary in Hungary itself, and that the Parliament should have authority over the Hungarian regiments of the Habsburg Army.

The new suffrage law (Act V of 1848) transformed the old feudal estates based parliament (Estates General) into a democratic representative parliament. This law offered the widest suffrage right in Europe at the time.[28] The first general parliamentary elections were held in June, which were based on popular representation instead of feudal forms. The reform oriented political forces won the elections. The electoral system and franchise were similar to the contemporary British system.[29]

At that time the internal affairs and foreign policy of Hungary were not stable, and Batthyány faced many problems. His first and most important act was to organize the armed forces and the local governments. He insisted that the Austrian army, when in Hungary, would come under Hungarian law, and this was conceded by the Austrian Empire. He tried to repatriate conscript soldiers from Hungary. He established the Organisation of Militiamen, whose job was to ensure internal security of the country.

Batthyány was a very capable leader, but he was stuck in the middle of a clash between the Austrian monarchy and the Hungarian separatists. He was devoted to the constitutional monarchy and aimed to keep the constitution, but the Emperor was dissatisfied with his work.

Josip Jelačić was Ban (Viceroy) of Croatia and Dalmatia, regions included in the Kingdom of Hungary. He was opposed to the new Hungarian government, and raised troops in his domains.

In the summer of 1848, the Hungarian government, seeing the civil war ahead, tried to get the Habsburgs' support against Jelačić. They offered to send troops to northern Italy. In August 1848, the Imperial Government in Vienna officially ordered the Hungarian government in Pest not to form an army.

On 29 August, with the assent of parliament, Batthyány went with Ferenc Deák to the Emperor to ask him to order the Serbs to capitulate and stop Jelačić, who was going to attack Hungary. But Jelačić went ahead and invaded Hungary to dissolve the Hungarian government, without any order from Austria.

Though the Emperor formally relieved Jelačić of his duties, Jelačić and his army invaded Muraköz (Međimurje) and the Southern Transdanubian parts of Hungary on 11 September 1848.

After the Austrian revolution in Vienna was defeated, Franz Joseph I of Austria replaced his uncle Ferdinand I of Austria, who was not of sound mind. Franz Joseph didn't recognise Batthyány's second premiership, which began on 25 September. Also, Franz Joseph was not recognized as "King of Hungary" by the Hungarian parliament, and he was not crowned as "King of Hungary" until 1867. In the end, the final break between Vienna and Pest occurred when Field-Marshal Count Franz Philipp von Lamberg was given control of every army in Hungary (including Jelačić's). He went to Hungary where he was mobbed and viciously murdered. Following his murder the Imperial court dissolved the Hungarian Diet and appointed Jelačić as Regent.

Meanwhile, Batthyány travelled again to Vienna to seek a compromise with the new Emperor. His efforts remained unsuccessful, because Franz Joseph refused to accept the reform laws. This was an unconstitutional deed, because the laws were already signed by his uncle, and the monarch had no right to revoke laws which were already signed.

Hungarian liberals in Pest saw this as an opportunity. In September 1848, the Diet made concessions to the Pest Uprising, so as not to break up the Austro-Hungarian Union. But the counter-revolutionary forces were gathering. After many local victories, the combined Bohemian and Croatian armies entered Pest on 5 January 1849.[30]

So Batthyány and his government resigned, except for Kossuth, Szemere, and Mészáros. Later, on Palatine Stephen's request, Batthyány became Prime Minister again. On 13 September Batthyány announced a rebellion and requested that the Palatine lead them. However the Palatine, under the Emperor's orders, resigned and left Hungary.

Hungary now had war raging on three fronts: Jelačić's Croatian troops to the South, Romanians in Banat and in Transylvania to the East, and Austria to the west.

The Hungarian government was in serious military crisis due to the lack of soldiers, therefore they sent Kossuth (a brilliant orator) to recruit volunteers for the new Hungarian army. While Jelačić was marching on Pest, Kossuth went from town to town rousing the people to the defense of the country, and the popular force of the Honvéd was his creation.

With the help of Kossuth's recruiting speeches, Batthyány quickly formed the Hungarian Revolutionary Army. The new Hungarian army defeated the Croatians on 29 September at the Battle of Pákozd.

The battle became an icon for the Hungarian army for its effect on politics and morale. Kossuth's second letter for the Austrian people and this battle were the causes of the second revolution in Vienna on 6 October.

Batthyány slowly realized that he could not reach his main goal, peaceful compromise with the Habsburg dynasty. On 2 October he resigned and simultaneously resigned his seat in parliament. The ministers of his cabinet also resigned on the same day.

The Austrian Stadion Constitution and the renewal of antagonism

The Habsburg government in Vienna proclaimed a new constitution, the so-called Stadion Constitution on 4 March 1849.[31][32] The centralist Stadion Constitution provided very strong power for the monarch, and marked the way of neo-absolutism.[33] The new March Constitution of Austria was drafted by the Imperial Diet of Austria, where Hungary had no representation. Austrian legislative bodies like the Imperial Diet traditionally had no power in Hungary. Despite this, the Imperial Diet also tried to abolish the Diet of Hungary (which existed as the legislative power in Hungary since the late 12th century.)[34] Moreover, the Austrian Stadion constitution also went against the historical constitution of Hungary, and tried to nullify it too.[35]

The Hungarian Republic, Regent-President Lajos Kossuth

When Batthyány resigned he was appointed with Szemere to carry on the government provisionally, and at the end of September he was made President of the Committee of National Defense. Kossuth was elected by the parliament as the head of state of Hungary. With the exception of Kázmér Batthyány, all members of the new cabinet were formed from Kossuth's supporters.

New government (The Szemere government) was formed on 2 May 1849:[36][37]

Head of state, Lajos Kossuth.

Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior, Bertalan Szemere

Foreign Minister, Minister of Agriculture, Industry and Trade : Kázmér Batthyány

Finance Minister: Ferenc Duschek

Minister of Justice: Sebő Vukovics

Minister of Education, Science and Culture: Mihály Horváth

Minister of Labour, Infrastructure and Transport: László Csány

Minister of Defence: Lázár Mészáros (14 April 1849 – 1 May 1849) Artúr Görgey (7 May 1849 – 7 July 1849) and Lajos Aulich (14 July 1849 – 11 August 1849)

From this time he had increased amounts of power. The direction of the whole government was in his hands. Without military experience, he had to control and direct the movements of armies; he was unable to keep control over the generals or to establish that military co-operation so essential to success. Arthur Görgey in particular, whose abilities Kossuth was the first to recognize, refused obedience; the two men were very different personalities. Twice Kossuth deposed him from the command; twice he had to restore him. It would have been well if Kossuth had had something more of Görgey's calculated ruthlessness, for, as has been truly said, the revolutionary power he had seized could only be held by revolutionary means; but he was by nature soft-hearted and always merciful; though often audacious, he lacked decision in dealing with men. It has been said that he showed a want of personal courage; this is not improbable, the excess of feeling which made him so great an orator could hardly be combined with the coolness in danger required of a soldier; but no one was able, as he was, to infuse courage into others.

During all the terrible winter which followed, his energy and spirit never failed him. It was he who overcame the reluctance of the army to march to the relief of Vienna; after the defeat at the Battle of Schwechat, at which he was present, he sent Józef Bem to carry on the war in Transylvania. At the end of the year, when the Austrians were approaching Pest, he asked for the mediation of Mr William Henry Stiles (1808–1865), the American envoy. Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, however, refused all terms, and the Diet and government fled to Debrecen, Kossuth taking with him the Crown of St Stephen, the sacred emblem of the Hungarian nation. In November 1848, Emperor Ferdinand abdicated in favour of Franz Joseph. The new Emperor revoked all the concessions granted in March and outlawed Kossuth and the Hungarian government – set up lawfully on the basis of the April laws. In April 1849, when the Hungarians had won many successes, after sounding the army, Kossuth issued the celebrated Hungarian Declaration of Independence, in which he declared that "the house of Habsburg-Lorraine, perjured in the sight of God and man, had forfeited the Hungarian throne." It was a step characteristic of his love for extreme and dramatic action, but it added to the dissensions between him and those who wished only for autonomy under the old dynasty, and his enemies did not scruple to accuse him of aiming for Kingship. The dethronement also made any compromise with the Habsburgs practically impossible.

Kossuth played a key role in tying down the Hungarian army for weeks for the siege and recapture of Buda castle, finally successful on 21 May 1849. The hopes of ultimate success were, however, frustrated by the intervention of Russia; all appeals to the western powers were vain, and on 11 August Kossuth abdicated in favor of Görgey, on the ground that in the last extremity the general alone could save the nation. Görgey capitulated at Világos (now Şiria, Romania) to the Russians, who handed over the army to the Austrians.[20]

War of Independence

In 1848 and 1849, the Hungarian people or Magyars, who wanted independence, formed a majority only in the central areas of the country. The Hungarians were surrounded by other nationalities.

In 1848–49, the Austrian monarchy and those advising them manipulated the Croatians, Serbians and Romanians, making promises to the Magyars one day and making conflicting promises to the Serbs and other groups the next.[38] Some of these groups were led to fight against the Hungarian Government by their leaders who were striving for their own independence; this triggered numerous brutal incidents between the Magyars and Romanians among others.

In 1848 and 1849, however, the Hungarians were supported by most Slovaks, Germans, Rusyns and Hungarian Slovenes,[39][40][41] the Hungarian Jews, and many Polish, Austrian and Italian volunteers.[42] On 28 July 1849, the Hungarian Revolutionary Parliament proclaimed and enacted the first[43][44] laws on ethnic and minority rights in Europe, but these were overturned after the Russian and Austrian armies crushed the Hungarian Revolution.[45][46][47] Occasionally, the Austrian throne would overplay their hand in their tactics of divide and conquer in Hungary – with some quite unintended results. This happened in the case of the Slovaks who had begun the war as at least indifferent if not positively anti-Magyar, but came to support the Hungarian Government against the Dynasty.[48] But in another case, the Austrians' double-dealing brought some even more surprising new allies to the Hungarian cause during the war in 1849.

Croats

The kingdom of Croatia had been in a personal union with the kingdom of Hungary since the 12th century. Croatian nationalism was weak in the beginning of the 19th century, but grew with increasing Hungarian pressure, especially the April Laws that ignored Croatian autonomy under Hungarian Kingdom.[49]

In response, Croatian leaders called for a distinct Triune Kingdom. Ban Josip Jelačić, who would go on to be a revered Croatian hero, sought to free Croatia from Hungary as a separate entity under the Habsburgs. Eventually, he traveled to Vienna to take oaths to become counsel of Austrian Emperor. Soon after Lajos Kossuth declared an independent Kingdom of Hungary dethroning the Habsburgs, the Croats rebelled against the Hungarians and declared their loyalty to Austria. The first fighting in the Hungarian revolution was between the Croats and Magyars, and Austria's intervention on the part of their loyal Croatian subjects caused an upheaval in Vienna.[50] Josip sent his army under the order of him, hoping to suppress the increasing power of Hungarian revolutionaries, but failed and was repelled by the Hungarians in September 29 near Pákozd.[51]

With the end of Hungarian Revolution, Croatia would be directly ruled by Austria until the Croatian-Hungarian Settlement in the 1860s.[52]

Serbs of Vojvodina

Vojvodina became a Hungarian Crown Land after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in the Great Turkish War.

Between the Tisza river and Transylvania, north of the Danube lies the former region of Hungary called the "Banat".[53] After the Battle of Mohács, under Ottoman rule the area north of the Danube saw an influx of Southern Slavs along with the invading Ottoman army. In 1804 the semi-independent Principality of Serbia had formed south of the Danube with Belgrade as its capital. So in 1849, the Danube divided Serbia from the Kingdom of Hungary. The Hungarian district on the northern side of the river was called "Vojvodina", and by that time it was home to almost half a million Serbian inhabitants. According to the census of 1840 in Vojvodina Serbs comprised 49% of the total population. The Serbs of Vojvodina had sought their independence or attachment with the Principality of Serbia on the other side of the Danube. In face of the emerging Hungarian independence movement leading up to the 1848 Revolution the Austrian monarchy had promised an independent status for the Serbs of Vojvodina within the Austrian Empire.

Toward this end, Josif Rajačić was appointed Patriarch of Vojvodina in February 1849.[54] Rajačić was a supporter of the Serbian national movement, although somewhat conservative with pro-Austrian leanings. At a crucial point during the war against the Hungarian Government, in late March 1849 when the Austrians needed more Serbian soldiers to fight the war, the Austrian General Georg Rukavina Baron von Vidovgrad, who commanded the Austrian troops in Hungary, officially re-stated this promise of independence for Vojvodina and conceded to all the demands of the Patriarch regarding Serbian nationhood.[55] Acquiescence to the demands of the Patriarch should have meant a relaxation of the strict military administration of Vojvodina. Under this military administration in the border areas, any male between the ages of 16 years and 60 years of age could be conscripted into the army.[56]

The Serbs of Vojvodina were expecting their requirement for Austrian military conscription to be the first measure to be relaxed. But the new Emperor Franz Joseph had other ideas and this promise was broken not more than two weeks after it had been made to the people of Vojvodina. This caused a split in the population of the Vojvodina and at least part of the Serbs in that province began to support the elected Hungarian Government against the Austrians.[56] Some Serbs sought to ingratiate the Serb nation with the Austrian Empire to promote the independence of Vojvodina.

With war on three fronts the Hungarian Government should have been squashed immediately upon the start of hostilities. However, events early in the war worked in favor of the Government. The unity of the Serbs on the southern front was ruined by Austrian perfidy over the legal status of Vojvodina.

Some right-wing participants in the Serbian national movement felt that a "revolution" in Hungary more threatened the prerogatives of landowners, and the nobles in Serbian Vojvodina, than the occupying Austrians.[57]

At the start of the war, the Hungarian Defence Forces (Honvédség) won some battles[58][59] against the Austrians, for example at the Battle of Pákozd in September 1848 and at the Isaszeg in April 1849, at which time they even stated the Hungarian Declaration of Independence from the Habsburg Empire. The same month, Artúr Görgey became the new Commander-in-Chief of all the Hungarian Republic's armies.[60]

After the fall of the Hungarian revolution in 1849, Vojvodina became an Austrian Crown Land. In 1860 it became again a Hungarian Crown Land and was part of Hungary until the end of World War I.[61]

Western Slovak uprising

The Slovak Uprising was a reactionary movement to the Hungarian Revolution in the Western parts of Upper Hungary (now Western Slovakia).[62] However, the Slovak nation siding with Vienna is a widespread modern myth - they could hardly recruit around 2000 people from Upper Hungary - in fact the number of Slovaks fighting on the other side was at least two orders of magnitude greater. The Slovaks had a much higher percentage of their population serving in the Honvédség (Home Guard) than Hungarians.[63] The Slovak nation and people had been poorly defined up to this point, as the Slovak people lacked a definitive border or national identity. However, in the years leading up to the revolution, the Hungarians had taken steps to Magyarize the Slovak region under Hungarian control. The aim of this was to bring the varied ethnic groups around Hungary into a common culture. At the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution this process was seen as more imminent and threatening to ethnic groups, especially the Slovaks.[64]

The Slovaks made demands that their culture be spared Magyarization and that they be given certain liberties and rights. These demands soon broke out into demonstrations clamouring for the rights of ethnic minorities in Hungary. Arrests were made that further enraged the demonstrators and eventually a Pan-Slavic Congress was held in Prague. A document was drafted at this congress and sent to the Hungarian government demanding the rights of the Slovak people. The Hungarians responded by imposing martial law on the Slovak region.[64]

The Imperial government recognized that all across the Empire, ethnic minorities were seeking more autonomy, but it was only Hungary that desired a complete break. They used this by supporting the ethnic national movements against the Hungarian government. Slovak volunteer units were commissioned in Vienna to join campaigns against the Hungarians across the theatre. A Slovak regiment then marched to Myjava where a Slovak council openly seceded from Hungary. Tensions rose as the Hungarian army executed a number of Slovak leaders for treason and the fighting became more bloody.[64]

However, the Western Slovak uprising also wanted its autonomy from Hungary. Slovak leaders hoped that Upper Hungary would become part of Austrian part of the empire. Tensions with the Austrians soon began to rise. Lacking support and with increased Hungarian efforts, the Slovak volunteer corps had little impact for the rest of the war until the Russians marched in. It was used in 'mopping up' resistance in the wake of the Russian advance and then soon after was disbanded, ending Slovak involvement in the Revolution. The conclusion of the uprising is unclear, as the Slovaks fell back under Imperial authority and lacked any autonomy for some time.[64]

Transylvania

On 29 May 1848, at Kolozsvár (now Cluj, Romania), the Transylvanian Diet (formed of 116 Hungarians, 114 Székelys and 35 Saxons[65]) ratified the re-union with Hungary. Romanians and Germans disagreed with the decision.[66]

On 10 June 1848 the newspaper Wiener Zeitung wrote: In any case, the union of Transylvania, proclaimed against all human rights, is not valid, and the courts of law in the entire world must admit the justness of the Romanian people's protest[67]

Romanians

On 25 February 1849 the representatives of the Romanian population sent to the Habsburg Emperor The Memorandum of the Romanian nation from the Great Principality of Transylvania, Banat, from neighbouring territories to Hungary and Bukovina where they demanded the union of Bukovina, Transylvania and Banat under a government (...) the union of all Romanians in the Austrian state into one single independent nation under the rule of Austria as completing part of the Monarchy[68]

Transylvanian Saxons

In the first days of October 1848, Stephan Ludwig Roth considered that there were two options for the Saxons: The first is to side with the Hungarians, and thus turn against the Romanians and the empire; the second is to side with the Romanians, and thus support the empire against the Hungarians. In this choice, the Romanians and Hungarians are incidental factors. The most important principle is that of a united empire, for it guarantees the extension of Austria's proclaimed constitution.[69]

The Transylvanian Saxons rejected the incorporation of Transylvania into Hungary.[70]

Russians

Because of the success of revolutionary resistance, Franz Joseph had to ask for help from the "gendarme of Europe"[71] Tsar Nicholas I of Russia in March 1849. A Russian army, composed of about 8,000 soldiers, invaded Transylvania on 8 April 1849.[72] But as they crossed the Southern Carpathian mountain passes (along the border of Transylvania and Wallachia), they were met by a large Hungarian revolutionary army led by Józef Bem, a Polish-born General.[73]

Bem had been a participant in the Polish insurrection of 1830–31, had been involved in the uprising in Vienna in 1848 and, finally, became one of the top army commanders for the Hungarian Republic from 1848–49.[74] When he encountered the Russians, Bem defeated them and forced them back out of the towns of Hermannstadt (now Sibiu, Romania) and Kronstadt (now Brașov) in Transylvania, back over the Southern Carpathian Mountains through the Roterturm Pass into Wallachia.[74] Only 2,000 Russian soldiers made it out of Transylvania back into Wallachia, the other 6,000 troops being killed or captured by the Hungarian Army.[75] After securing all of Transylvania, Bem moved his 30,000–40,000-man Hungarian army against Austrian forces in the northern Banat capturing the city of Temesvár (now Timișoara, Romania).[76]

Austrians

Laval Nugent von Westmeath was the Austrian Master of Ordnance, but was serving as the general in the field attempting to marshall all the Serbs still loyal to the Austrian throne, for another offensive against the Hungarian Government.[77] Here, even on the southern front the Hungarian Armies were proving successful, initially.

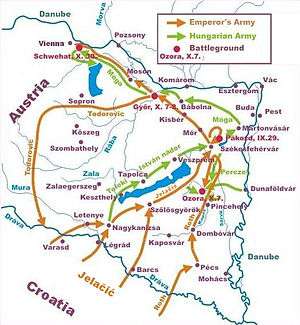

This combat led to the Vienna Uprising of October 1848, when insurgents attacked a garrison on its way to Hungary to support forces. However, the Austrian army was able to quell the rebellion. At the same time, at Schwechat, the Austrians defeated a Hungarian attempt to capture Vienna. After this victory, General Windischgrätz and 70,000 troops were sent to Hungary to crush the Hungarian revolution. the Austrians followed the Danube down from Vienna and crossed over into Hungary to envelope Komorn (now Komárom, Hungary and Komárno, Slovakia). They continued down the Danube to Pest, the capital of the Hungarian Kingdom. After some fierce fighting, the Austrians, led by Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, captured Buda and Pest.[78] (the town was known in German as Ofen and later Buda and Pest were united into Budapest).

In April 1849, after these defeats, the Hungarian Government recovered and scored several victories on this western front. They stopped the Austrian advance and retook Buda and Pest. [79] Then, the Hungarian Army relieved the siege of Komárom. [80] The spring offensive hence proved to be a great success for the revolution.

Thus, the Hungarian Government was equally successful on its eastern front (Transylvania) against the Russians, and on its western front against the Austrians. But there was a third front – the southern front in the Banat, fighting the troops of the Serbian national movement and the Croatian troops of Jelačić within the province of Vojvodina itself. Mór Perczel, the General of the Hungarian forces in the Banat, was initially successful in battles along the southern front.[81]

In April 1849, Ludwig Baron von Welden replaced Windischgrätz as the new supreme commander of Austrian forces in Hungary.[82] Instead of pursuing the Austrian army, the Hungarians stopped to retake the Fort of Buda and prepared defenses. At the same time, however, victory in Italy had freed many Austrian troops which had hitherto been fighting on this front. In June 1849 Russian and Austrian troops entered Hungary heavily outnumbering the Hungarian army. After all appeals to other European states failed, Kossuth abdicated on August 11, 1849 in favour of Artúr Görgey, who he thought was the only general who was capable of saving the nation.

However, in May 1849, Tsar Nicholas I pledged to redouble his efforts against the Hungarian Government. He and Emperor Franz Joseph started to regather and rearm an army to be commanded by Anton Vogl, the Austrian lieutenant-field-marshal who had actively participated in the suppression of the national liberation movement in Galicia in 1848.[83] But even at this stage Vogl was occupied trying to stop another revolutionary uprising in Galicia.[84] The Tsar was also preparing to send 30,000 Russian soldiers back over the Eastern Carpathian Mountains from Poland. Austria held Galicia and moved into Hungary, independent of Vogl's forces. At the same time, the able Julius Jacob von Haynau led an army of 60,000 Austrians from the West and retook the ground lost throughout the spring. On July 18, he finally captured Buda and Pest.[85] The Russians were also successful in the east and the situation of the Hungarians became increasingly desperate.

On August 13, after several bitter defeats, especially the battle of Segesvár against the Russians and the battles of Szöreg and Temesvár [85] against the Austrian army, it was clear that Hungary had lost. In a hopeless situation, Görgey signed a surrender at Világos (now Şiria, Romania) to the Russians (so that the war would be considered a Russian victory and because the rebels considered the Russians more lenient), who handed the army over to the Austrians.[86]

Aftermath

Julius Jacob von Haynau, the leader of the Austrian army, was appointed plenipotentiary to restore order in Hungary after the conflict. He ordered the execution of The 13 Martyrs of Arad (now Arad, Romania) and Prime Minister Batthyány was executed the same day in Pest.[86]

After the failed revolution, in 1849 there was nationwide "passive resistance".[87] In 1851 Archduke Albrecht, Duke of Teschen was appointed as Regent, which lasted until 1860, during which time he implemented a process of Germanisation.[88]

Kossuth went into exile after the revolution, initially gaining asylum in the Ottoman Empire, where he resided in Kütahya until 1851. That year the US Congress invited him to come to the United States. He left the Ottoman Empire in September, stopped in Britain, then arrived in New York in December. In the US he was warmly received by the general public as well as the then US Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, which made relations between the US and Austria somewhat strained for the following twenty years. Kossuth County, Iowa was named for him. He left the United States for England in the summer of 1852. He remained there until 1859, when he moved to Turin, at the time the capital of Piedmont-Sardinia, in hopes of returning to Hungary. He never did.

Kossuth thought his biggest mistake was to confront the Hungarian minorities. He set forth the dream of a multi-ethnic confederation of republics along the Danube, which might have prevented the escalation of hostile feelings between the ethnic groups in these areas.[89]

Many of Kossuth's comrades-in-exile joined him in the United States, including the sons of one of his sisters. Some of these "Forty-Eighters" remained after Kossuth departed, and fought on the Union side in the US Civil War. Hungarian lawyer George Lichtenstein, who served as Kossuth's private secretary, fled to Königsberg after the revolution and eventually settled in Edinburgh where he became noted as a musician.[90]

After the Hungarian Army's surrender at Világos in 1849, their revolutionary banners were taken to Russia by the Tsarist troops, and were kept there both under the Tsarist and Communist systems. In 1940 the Soviet Union offered the banners to the Horthy government in exchange for the release of the imprisoned Hungarian Communist leader Mátyás Rákosi – the Horthy government accepted the offer.[91]

According to legend the people of Hungary do not clink glasses with beer after the suppression of the revolution.[92]

Notes

References

- Rosonczy: OROSZ GYORSSEGÉLY BÉCSNEK 1849 TAVASZÁN (PhD disertation 2015)

- Dr Zachary C Shirkey: Joining the Fray: Outside Military Intervention in Civil Wars Military Strategy and Operational Art -PAGE: 1944- ISBN 1409470911, 9781409470915 Archived 2014-12-27 at the Wayback Machine

- A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle ..., by Spencer C. Tucker, 2009 p. 1188

- Eric Roman: Austria-Hungary & the Successor States: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present -PAGE: 67, Publisher: Infobase Publishing, 2003 ISBN 9780816074693

- The Making of the West: Volume C, Lynn Hunt, Pages 683–684

- In 1804 Emperor Franz assumed the title of Emperor of Austria for all the Erblande of the dynasty and for the other Lands, including Hungary. Thus Hungary formally became part of the Empire of Austria. The Court reassured the diet, however, that the assumption of the monarch’s new title did not in any sense affect the laws and the constitution of Hungary Laszlo, Péter (2011), Hungary's Long Nineteenth Century: Constitutional and Democratic Traditions, Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, the Netherlands, p. 6

- Robert Young (1995). Secession of Quebec and the Future of Canada. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 138. ISBN 9780773565470.

the Hungarian constitution was restored.

- Éva H. Balázs: Hungary and the Habsburgs, 1765–1800: An Experiment in Enlightened Absolutism. p. 320.

- Yonge, Charlotte (1867). "The Crown of St. Stephen". A Book of Golden Deeds Of all Times and all Lands. London, Glasgow and Bombay: Blackie and Son. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- Nemes, Paul (2000-01-10). "Central Europe Review — Hungary: The Holy Crown". Archived from the original on 2019-05-17. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- An account of this service, written by Count Miklos Banffy, a witness, may be read at The Last Habsburg Coronation: Budapest, 1916. From Theodore's Royalty and Monarchy Website.

- András A. Gergely; Gábor Máthé (2000). The Hungarian state: thousand years in Europe : [1000-2000]. Korona. p. 66. ISBN 9789639191792.

- Charles W. Ingrao : The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618–1815, Volume 21 of New Approaches to European History, Publisher: Cambridge University Press, 2000 ISBN 9781107268692

- Jean Berenger, C.A. Simpson: The Habsburg Empire 1700-1918 , Publisher: Routledge, 2014, ISBN 9781317895725

- Tomasz Kamusella: The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe, Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, ISBN 9780230550704

- Paschalis M. Kitromilides: Enlightenment and Revolution, Publisher: Harvard University Press, 2013, ISBN 9780674726413

- Peter McPhee: A Companion to the French Revolution -PAGE: 391 , Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, 2014, ISBN 9781118977521

- Ödön Beöthy and Tibor Vágvölgyi: A Magyar Jakobinusok Köztársasági Mozgalma, -PAGE: 103 Budapest 1968, English: The Hungarian jacobin republican movement.

- Lendvai, Paul (2002), The Hungarians: A Thousand Years of Victory in Defeat, C Hurst & Co, p. 194, ISBN 978-1-85065-682-1

-

- Mihály Lackó: Széchenyi és Kossuth vitája, Gondolat, 1977.

- See: Lacko p. 47

- Gróf Széchenyi István írói és hírlapi vitája Kossuth Lajossal [Count Stephen Széchenyi,s Literary and Publicistic Debate with Louis Kossuth], ed. Gyula Viszota, 2 vols. (Budapest: Magyar Történelmi Társulat, 1927–1930).

- "március15". marcius15.kormany.hu. Archived from the original on 2017-09-17. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- Charles Frederick Henningsen: Kossuth and 'The Times', by the author of 'The revelations of Russia'. 1851 -PAGE: 10

- Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, Tibor Frank: A History of Hungary (Indiana University Press, Jan 1, 1994) -PAGE: 213

- "Az áprilisi törvények (English: "The April laws")" (in Hungarian). March 22, 1999. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- prof. András Gerő (2014): Nationalities and the Hungarian Parliament (1867-1918) LINK:

- Steven A. Seidman and Peter Lang. Posters, Propaganda, and Persuasion in Election Campaigns Around the World. p. 201

- Gazi, Stephen (1973). A History of Croatia. New York: Barnes and Noble Books. p. 150.

- Schjerve, Rosita Rindler (2003). Diglossia and Power: Language Policies and Practice in the 19th Century Habsburg Empire. Language, Power, and Social Process. 9. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 75–76. ISBN 9783110176544.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mahaffy, Robert Pentland (1908). Francis Joseph I.: His Life and Times. Covent Garden: Duckworth. p. 39.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walther Killy (2005). Dictionary of German biography. 9: Schmidt-Theyer. Walter de Gruyter. p. 237. ISBN 9783110966299.

- Július Bartl (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. p. 222. ISBN 9780865164444.

- Paul Bődy (1989). Hungarian statesmen of destiny, 1860-1960. Atlantic studies on society in change, 58; East European monographs, 262. Social Sciences Monograph. p. 23. ISBN 9780880331593.

- Romsics, Béla K. Király: Geopolitics in the Danube Region: Hungarian Reconciliation Efforts 1848-1998 -PAGE: 413 , Publisher: Central European University Press, 1999, ISBN 9789639116290

- Greger-Delacroix: The Reliable Book of Facts: Hungary '98 -PAGE: 32

- Marx & Engels, p. 229.

- "Kik voltak a honvédek". www.vasidigitkonyvtar.hu (The Hungarian Peoples' Online Encyclopaedia) (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- Kozár, Mária; Gyurácz, Ferenc. Felsőszölnök, Száz magyar falu könyvesháza. KHT. ISBN 963-9287-20-2.

- Források a Muravidék történetéhez/Viri za zgodovino Prekmurja. 1. Szombathely-Zalaegerszeg. 2008. ISBN 978-963-7227-19-6.

- Jeszenszky, Géza (17 November 2000). "From "Eastern Switzerland" to Ethnic Cleansing, address at Duquesne History Forum" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2013.

- Mikulas Teich; Roy Porter (1993). The National Question in Europe in Historical Context. Cambridge University Press. p. 256. ISBN 9780521367134.

- Ferenc Glatz (1990). Etudes historiques hongroises 1990: Ethnicity and society in Hungary, Volume 2. Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. p. 108. ISBN 9789638311689.

- Tötösy de Zepetnek, Steven; Vasvari, Louise O. (2011). Comparative Hungarian Cultural Studies. p. 50. ISBN 9781557535931.

- Spira, György (1992). The nationality issue in the Hungary of 1848-49. ISBN 9789630562966.

- Ronen, Dov; Pelinka, Anton (1997). The challenge of ethnic conflict, democracy and self-determination in Central Europe. p. 40. ISBN 9780714647524.

- Marx & Engels, p. 390, 3 May 1848.

- "Nationalism in Hungary, 1848-1867".

- "Heritage History - Products".

- "Hungary's War of Independence". 2006-09-05.

- Horváth, Eugene (1934). "Russia and the Hungarian Revolution (1848-9)". The Slavonic and East European Review. 12 (36): 628–645. JSTOR 4202930.

- Kinder, Herman; Hilgeman, Werner (1978). The Anchor Atlas of world History. 2. Garden City, New York: Anchor Books. p. 58.

- Marx & Engels, p. 613.

- Marx & Engels, p. 250, The War in Hungary.

- Marx & Engels, 8 April 1848.

- Judah 1997, p. 60.

- "Pákozd-Sukoró Battle 1848 Exhibition" (in Hungarian). Pákozd. September 29, 1998. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Isaszeg". 1hungary.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- Marx & Engels, p. 603.

- Geert-Hinrich Ahrens (2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press Series. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. p. 243. ISBN 9780801885570.

- Mikuláš Teich, Dušan Kováč, Martin D. Brown (2011). Slovakia in History. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9781139494946. Archived from the original on 2017-02-08.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Páva, István (1999-08-01). "Szlovákok a magyar szabadságharcban". magyarszemle.hu. Magyar szemle.

- Špiesz, Anton (2006), Illustrated Slovak History, Wauconda, Illinois: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, ISBN 0-86516-500-9

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-05-14. Retrieved 2014-05-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Pál Hatos and Attila Novák (editors). Between Minority and Majority. Hungarian and Jewish/Israeli Ethnical and Cultural Experiences in Recent Centuries

- Centrul de Studii Transilvane; Fundația Culturală Română (1998). Transylvanian Review. Romanian Cultural Foundation. ISSN 2067-1016. Archived from the original on 20 June 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- http://www.brukenthalmuseum.ro/pdf/BAM/BRUKENTHALIA_1.pdf

- "Counter-revolution and Civil War". mek.oszk.hu. Archived from the original on 20 June 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Miklós Molnár. A Concise History of Hungary"

- "The Gendarme of Europe". www.writewellgroup.com. 12 August 2010. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- Marx & Engels, pp. 242, 262, 8 April 1849.

- Eugene Horváth, "Russia and the Hungarian Revolution (1848-9)." Slavonic and East European Review 12.36 (1934): 628-645. online

- Marx & Engels, p. 319, 22 April 1848.

- Marx & Engels, p. 242, 22 April 1848.

- Marx & Engels, p. 334.

- Marx & Engels, p. 611.

- Marx & Engels, p. 343.

- Marx & Engels, p. 304.

- Marx & Engels, p. 346.

- Marx & Engels, p. 331.

- Marx & Engels, p. 293, 19 April 1849.

- Marx & Engels, p. 618.

- Marx & Engels, p. 303.

- The Cambridge modern history; Leathes, Prothero and Vard

- Szabó, János B. (5 September 2006). "Hungary's War of Independence". historynet.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- (in Hungarian) Tamás Csapody: Deák Ferenc és a passzív rezisztencia Archived 2012-04-03 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kormányzat". gepeskonyv.btk.elte.hu. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- "Encyclopædia Britannica: Kossuth article"

- Musical Times (digitized online by GoogleBooks). 34. 1893. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- "Mátyás Rákosi". September 12, 2001. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Pityer. "Szabad-e sörrel koccintani?". Retró Legendák (in Hungarian). Retrieved 2019-10-08.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hungarian Revolution of 1848. |

- Barany, George. "The awakening of Magyar nationalism before 1848." Austrian History Yearbook 2 (1966) pp: 19-50.

- Cavendish, Richard. "Declaration of Hungary's Independence: April 14th, 1849." History Today 49#4 (1999) pp: 50-51

- Deák, István. Lawful Revolution: Louis Kossuth and the Hungarians 1848-1849 (Phoenix, 2001)

- Deme, László. "The Society for Equality in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848." Slavic Review (1972): 71-88. in JSTOR

- Gángó, Gábor. "1848-1849 in Hungary," Hungarian Studies (2001) 15#1 pp 39–47. online

- Horváth, Eugene. "Russia and the Hungarian Revolution (1848-9)." Slavonic and East European Review 12.36 (1934): 628-645. online

- Judah, Tim (1997). The Serbs: History, Myth & the Destruction of Yugoslavia. New Haven, CT, USA: Yale. ISBN 978-0-300-08507-5.

- Kosáry, Domokos G. The press during the Hungarian revolution of 1848-1849 (East European Monographs, 1986)

- Szilassy, Sandor. "America and the Hungarian Revolution of 1848-49." Slavonic and East European Review (1966): 180-196. in JSTOR